Models to Study the Evolutionary Origins of Multicellularity

The evolution of multicellular organisms from unicellular ancestors is one of the major transitions of evolution (Maynard Smith & Szathmáry Reference Maynard Smith and Szathmáry1995). It paved the way for new kinds of organisms that were more complex than their unicellular ancestors in terms of scale, organization, behaviours and life cycles. While multicellularity has evolved dozens of times independently (Grosberg & Strathmann Reference Grosberg and Strathmann2007), much remains to be learned about the early steps of this major evolutionary transition. Much of what we know has been inferred from limited geological and fossilized remains (Knoll Reference Knoll2011), or through phylogenetically-informed comparisons among living organisms (King Reference King2004; Suga et al. Reference Suga, Chen, de Mendoza, Sebé-Pedrós, Brown, Kramer, Carr, Kerner, Vervoort and Sánchez-Pons2013; Nagy et al. Reference Nagy, Kovács and Krizsán2018). Importantly, we lack basic knowledge about the diversity of possible routes to multicellularity and how increased complexity arises de novo.

In the last decade, laboratory model systems have provided some insight into how simple multicellularity can evolve. These systems rely on experimental evolution techniques that subject single-celled microbes to a selective regime that promotes the evolution of replicating groups of cells. While replicating groups of cells are a far cry from a fully-fledged multicellular organism, this is usually considered a necessary first step. One model system produced by this approach is snowflake yeast, which evolved from unicellular Baker's yeast (Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Denison, Borrello and Travisano2012) in response to artificial selection for rapid settling through liquid growth media. Since clusters of cells settle more quickly than solitary cells, this selective regime leads to the evolution of yeast mutants that do not separate after reproduction. The genetics underlying this change are remarkably simple and repeatedly involve a single gene, ACE2, which plays a key role in regulating mother-daughter cell separation after mitosis (Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Fankhauser, Rogers, Greig and Travisano2015; Tan et al. Reference Tan, He, Pentz, Peng, Yang, Tsai, Chen, Ratcliff and Jiang2019). Loss of function mutations in this gene produce yeast that grow as fractal-like trees of connected cells, with a highly conserved topology (Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Fankhauser, Rogers, Greig and Travisano2015).

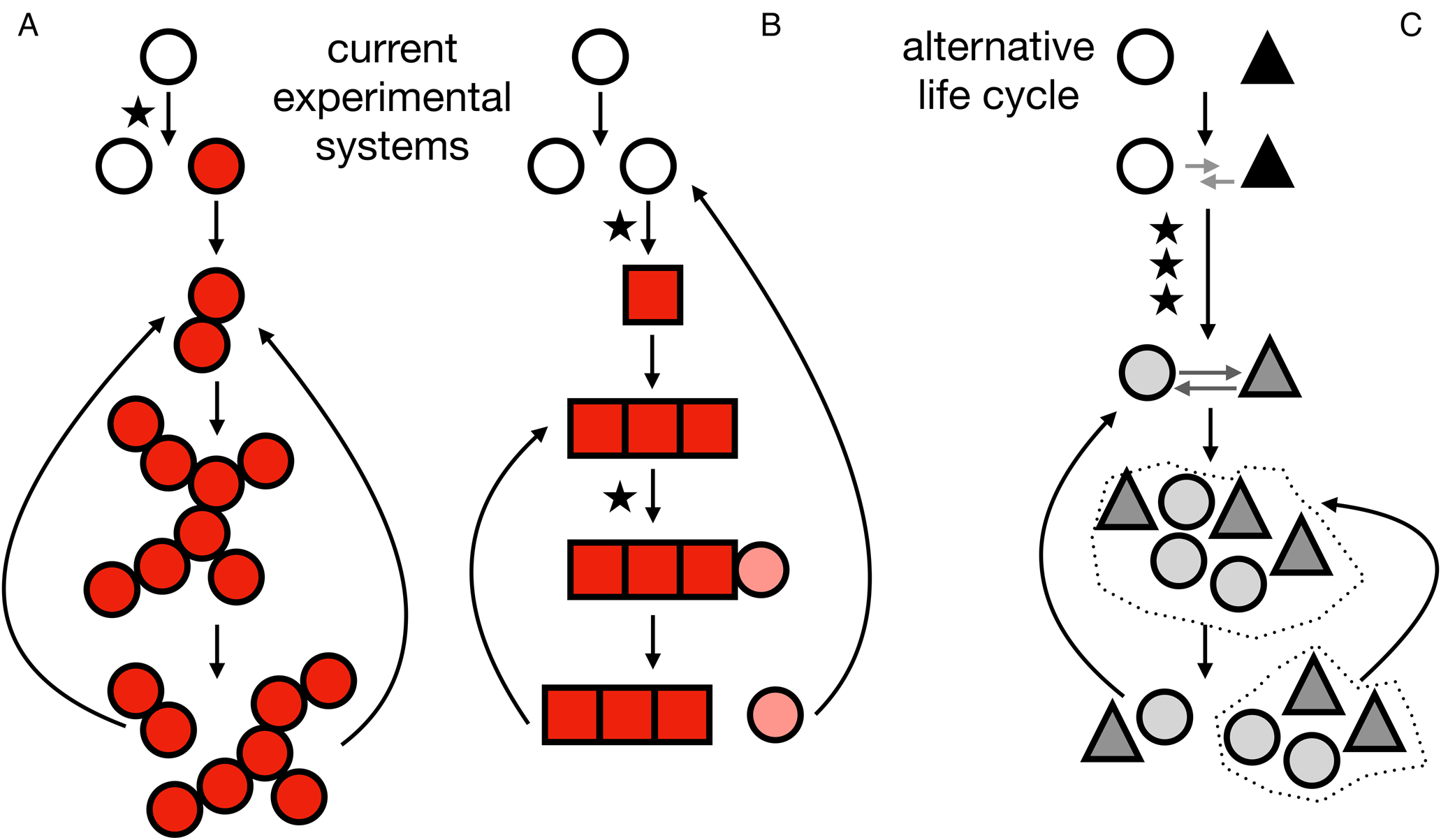

Reproduction in snowflake clusters occurs as a natural consequence of growth (see Fig. 1A). As snowflake clusters grow, they run out of space in the central parts of the group, leading to the accumulation of cell-cell strain and eventually group fracture (Libby et al. Reference Libby, Ratcliff, Travisano and Kerr2014; Jacobeen et al. Reference Jacobeen, Graba, Brandys, Day, Ratcliff and Yunker2018a, Reference Jacobeen, Pentz, Graba, Brandys, Ratcliff and Yunkerb). Group fracture provides a key attribute: it allows groups to reproduce, propagating themselves by severing branches, which themselves grow up to their parent's size before fracturing. This process allows groups to function as units of selection, surviving or dying as a unit depending on whether they can settle to the bottom of a test tube quickly enough. Continued evolution in this experiment has seen novel group-level traits arise through changes in cell-level traits which affect the way that cells interact within the group. For example, groups evolve to be considerably larger by evolving more elongate cells, which generates more room for cellular movement within the cluster and reduces strain-based fragmentation (Jacobeen et al. Reference Jacobeen, Graba, Brandys, Day, Ratcliff and Yunker2018a, Reference Jacobeen, Pentz, Graba, Brandys, Ratcliff and Yunkerb).

Fig. 1. Life cycles at the origins of multicellularity. A, life cycle corresponding to the snowflake yeast. A mutation (indicated by a star) results in a mutant (indicated by red/filled circles) that cannot separate from its daughter cells. As cells reproduce the group increases in size until fragmentation results in two daughter groups that then repeat the life cycle. B, life cycle corresponding to the smooth-wrinkly system of Pseudomonas fluorescens. A mutation causes a phenotypic switch (indicated by a different, square-shaped cell). The group grows until another mutation recapitulates a phenotypic state similar to the unicellular ancestor, completing the life cycle. C, an example of an alternative multicellular life cycle not explored in current experimental systems. It begins with two different species (indicated by a white circle and a black triangle). An initial interaction (indicated by grey arrows) evolves through several mutations (indicated by stars) to become a more interdependent, possibly regulated, relationship. The multicellular life cycle is then repeated through population expansions and dispersal events (the dotted lines represent environmental patches). In colour online.

Similar experimental approaches selecting for larger groups have led other unicellular organisms to evolve multicellularity. For example, experimental evolution of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a unicellular relative of the multicellular volvocine green algae, under selection for rapid sedimentation resulted in the evolution of multicellular groups (Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Herron, Howell, Pentz, Rosenzweig and Travisano2013). Chlamydomonas reinhardtii evolved a similar life cycle in a different experiment where it was exposed to size selection, this time via the presence of a gape-limited predator (Herron et al. Reference Herron, Borin, Boswell, Walker, Chen, Knox, Boyd, Rosenzweig and Ratcliff2019). As with snowflake yeast, the groups grew until physical strain caused them to fracture into smaller groups. The repeated evolution of multicellular life cycles that rely on stress-mediated fragmentation for reproduction across experimental systems probably reflects common features of the experiments, including clonal population growth and a population bottleneck imposed through size selection.

A qualitatively different experimental system for studying multicellularity uses the SBW25 strain of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens (see Fig. 1B). In this system, the experimental protocol exploits a phenotypic switch that regularly evolves when SBW25 is cultured in liquid media (Rainey & Travisano Reference Rainey and Travisano1998; Rainey & Rainey Reference Rainey and Rainey2003). Initially, SBW25 expresses a unicellular phenotype that is characterized by the smooth colonies it forms when grown on plates. As a consequence of rapid reproduction, the ‘smooth’ cells reliably produce mutants, called ‘wrinkly’ cells. The wrinkly cells have a mutation, typically in one of three pathways, that disrupts regulation of the wss operon (Lind et al. Reference Lind, Farr and Rainey2015). Dysregulation of the wss operon causes wrinkly cells to overproduce extracellular cellulose and stick to their offspring, forming mats. The expanding population of smooth and wrinkly cells consume the oxygen in the media within a day and the only available oxygen is at the air-liquid interface (Koza et al. Reference Koza, Moshynets, Otten and Spiers2011). Due to their mat formation, the wrinkly types colonize this niche and benefit from access to oxygen. As the wrinkly cells reproduce, they give rise to new mutants that do not produce cellulose and, thus, resemble the ancestral smooth phenotype. After a few days, the mat collapses and releases these new smooth mutants into the broth, thereby completing a life cycle. The new smooth mutants can then be cultured in fresh media to repeat the process.

The Pseudomonas fluorescens system demonstrates how a multicellular life cycle can emerge by exploiting pre-existing traits. Many unicellular organisms make adhesive polymers to interact with each other and their environment (Dunne Reference Dunne2002). It seems plausible that modification of these adhesive molecules can lead to the formation of groups of cells, and then subsequent modifications can produce single cells. Although relying on mutations to switch adhesive molecule production on and off may be cumbersome, it is also possible for an epigenetic mechanism to evolve. Again, the Pseudomonas fluorescens system illustrates how this might occur. Clonal populations of P. fluorescens, the SBW25 strain in particular, can exhibit cell to cell variability in the production of adhesive polymers (Gallie et al. Reference Gallie, Libby, Bertels, Remigi, Jendresen, Ferguson, Desprat, Buffing, Sauer and Beaumont2015). The underlying variability might be accidental or adaptive, potentially acting as a bet-hedging trait. Regardless, mutations can enhance this stochastic phenotypic variation to generate mixed populations of cells: those producing significant quantities of adhesive molecules and those not making any (Gallie et al. Reference Gallie, Libby, Bertels, Remigi, Jendresen, Ferguson, Desprat, Buffing, Sauer and Beaumont2015). Lineages of cells can then switch between making adhesive molecules or not, giving rise to a phenotypic switch similar to one found in the smooth-wrinkly life cycle without the need for mutations. Thus, the evolution of multicellularity might harness unicellular pre-adaptations or survival strategies and modify their frequency to reliably produce replicating groups of cells.

In concert with these experimental approaches, theoretical work has sought to extract general principles underlying the transition to multicellularity. As in the experimental approaches, theoretical models typically focus on simple replicating groups of cells (Roze & Michod Reference Roze and Michod2001; Gavrilets Reference Gavrilets2010; Libby & Rainey Reference Libby and Rainey2013a; Tarnita et al. Reference Tarnita, Taubes and Nowak2013) and consider the various ways they can originate, persist, or evolve. Models that investigate the origination of multicellularity often identify environmental or ecological conditions that select for the formation of groups, such as avoiding predation (Boraas et al. Reference Boraas, Seale and Boxhorn1998; Herron et al. Reference Herron, Borin, Boswell, Walker, Chen, Knox, Boyd, Rosenzweig and Ratcliff2019), surviving stressful conditions (Smukalla et al. Reference Smukalla, Caldara, Pochet, Beauvais, Guadagnini, Yan, Vinces, Jansen, Prevost and Latgé2008), gaining metabolic advantages (Koschwanez et al. Reference Koschwanez, Foster and Murray2011), or colonizing new niches (Bonner Reference Bonner2009). Models that investigate the persistence of multicellularity typically determine traits or conditions that prevent groups of cells from reverting to unicellular forms, for example ratcheting traits that confer fitness benefits to groups but fitness costs to single cells (Libby & Ratcliff Reference Libby and Ratcliff2014; Libby et al. Reference Libby, Conlin, Kerr and Ratcliff2016). Lastly, models that investigate the evolution of early multicellularity explore how aspects of the group or its life cycle affect the rate of adaptation or what novel traits emerge (Roze & Michod Reference Roze and Michod2001; Willensdorfer Reference Willensdorfer2009; Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Herron, Conlin and Libby2017). Together these models have revealed many insights, especially concerning the variety of paths to evolving multicellularity and the significant ways in which these paths dictate future evolution.

As a result of this theoretical and experimental work, a consensus of the evolutionary dynamics driving the origin of simple multicellularity has emerged. First, single-celled organisms must evolve into simple multicellular groups. Then, these multicellular groups must become ‘units of selection’ that are capable of reproduction and evolution by selection, acquiring multicellular or ‘group-level’ adaptations. For example, groups may evolve a reproductive division of labour among constituent cells such that there are somatic and germ cells. Importantly, the group-level adaptations must resist cell-level adaptations, such as cancer, over evolutionary timescales (Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2009). Finally, the group of cells becomes an evolutionary individual in its own right when its fitness is more than an additive function, for example average, of the fitnesses of its constituent cells (Michod Reference Michod2005; Okasha Reference Okasha2006).

Alternative Evolutionary Routes to Multicellularity

There is an important caveat to the experimental and theoretical work discussed: it explores a particular set of paths to multicellularity in which the initial transition between unicellularity and multicellularity is mediated by mutations that directly result in the formation of multicellular groups. In snowflake yeast, loss of function in the ACE2 transcription factor causes a unicellular yeast to grow as a multicellular group (Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Fankhauser, Rogers, Greig and Travisano2015). In the smooth-wrinkly P. fluorescens system the mutation could occur in any of the pathways regulating expression of the wss operon, though they repeatedly occur more often in a particular negative regulator wspF (Bantinaki et al. Reference Bantinaki, Kassen, Knight, Robinson, Spiers and Rainey2007; Lind et al. Reference Lind, Farr and Rainey2015). While the specific genes required for multicellular growth in experimentally evolved Chlamydomonas are not well resolved, mutations were over-represented in cell cycle and reproductive processes, and in volvocine-specific genes (Herron et al. Reference Herron, Ratcliff, Boswell and Rosenzweig2018). For snowflake yeast and mat-forming Pseudomonas, multicellular and unicellular forms can be transformed into each other through altering just one gene in one cell. This transmutability makes these systems useful for controlled scientific studies, but it may not be a hallmark of all evolutionary routes to multicellularity.

To identify possible alternative paths to multicellularity, we first consider what is required for the evolution of replicating groups of cells. In particular, we note that there are three basic requirements: 1) there needs to be more than one cell involved, 2) the collection of cells needs to form something with a group structure, and 3) the group needs a way of replicating (Libby & Rainey Reference Libby and Rainey2013a). Of the three requirements, the second perhaps needs clarification concerning its role. In essence, the structure of a group acts to distinguish primitive multicellularity from an arbitrary collection of cells. It ensures that there is a distinction between members and non-members of a group, by requiring some connection, either direct or indirect, between cells in the same group. Cells can then share the benefits of being in the same group and contribute to its survival along with any emergent group-level traits. If we consider these three requirements within the snowflake yeast system, we see that all three are provided by a mutation in ACE2. By causing cells to stay attached following reproduction, the mutation connects all cells in a group and causes them to experience the same evolutionary fate: cells live or die if their groups live or die. Since the connection between cells can break under strain, there is also a mechanism for group reproduction. If we turn to the P. fluorescens experimental model, we see that the initial mutation that generates a wrinkly type satisfies requirements 1 and 2 but does not provide a mechanism for group replication; that has to come from a second mutation which restores the original phenotype. However, the abundance of paths between smooth and wrinkly types allows all three requirements to be met (Lind et al. Reference Lind, Farr and Rainey2015).

Starting with a single unicellular species, it is difficult to envision an evolutionary path to multicellularity that does not first involve a mutation leading to the formation of groups, satisfying requirements 1 and 2. Thus, we consider an alternative possibility in which a group of cells does not evolve from a single unicellular species but through the interaction of at least two different species. In this scenario, the first requirement is immediately satisfied. The second and third requirements imply that the community of cells must evolve a group structure and some way of propagating the community (i.e. a mode of replication) (see Fig. 1C). Indeed, selection on interacting unicellular organisms has been considered a path for ‘egalitarian’ transitions (Queller Reference Queller1997) to multicellularity, in which unrelated unicellular organisms come together to form a new kind of multicellular organism (Pande et al. Reference Pande, Merker, Bohl, Reichelt, Schuster, de Figueiredo, Kaleta and Kost2014; Szathmáry Reference Szathmáry2015; Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2016). In a sense, the origin of eukaryotic cells from a symbiosis between an archaeal host and an endosymbiotic alphaproteobacterium (Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka et al. Reference Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka, Caceres, Saw, Bäckström, Juzokaite, Vancaester, Seitz, Anantharaman, Starnawski and Kjeldsen2017) is a form of egalitarian multicellularity.

One challenge in considering a path to multicellularity that starts with two different species is determining the initial type of interaction between the species. There are many possible initial population structures involving two different species, and it is possible that some are much more likely than others to yield a form of multicellularity. To limit the scope, we draw inspiration from two examples of multi-species systems with evolvable group-level phenotypes: microbial syntrophies and lichens. We note that neither is a canonical multicellular organism and there are probably key aspects of their particular evolution that is sui generis. Nonetheless, we can adopt a theoretical approach and use general features of their evolution to explore the potential trajectories from a collection of different unicellular species to a type of simple multicellularity (i.e. replicating groups of cells).

Lichens and Microbial Syntrophies as Higher-level Units

A defining trait of both microbial syntrophies and lichens is an interdependent relationship between different species. In microbial syntrophies, relationships are typically mediated by the production or exchange of biochemical compounds or metabolites (Stams & Plugge Reference Stams and Plugge2009; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Henneberger, Huber and Moissl-Eichinger2013). For instance, methanogenic archaea and fermenting bacteria have a syntrophic relationship that allows them to survive the harsh conditions of hydrothermal vents (Schink Reference Schink and Overmann2005). The archaea consume the hydrogen waste of fermenting bacteria which would otherwise accumulate and inhibit their ability to ferment. The pair of microbes have complementary metabolisms such that through the exchange of compounds they can survive together in an environment where they would struggle in isolation. In comparison to microbial syntrophies, lichen relationships are more complex and vary between partners and species (Hawksworth Reference Hawksworth1988; Armaleo & Clerc Reference Armaleo and Clerc1991; Richardson Reference Richardson1999; Grube & Berg Reference Grube and Berg2009; Spribille et al. Reference Spribille, Tuovinen, Resl, Vanderpool, Wolinski, Aime, Schneider, Stabentheiner, Toome-Heller and Thor2016; Tuovinen et al. Reference Tuovinen, Ekman, Thor, Vanderpool, Spribille and Johannesson2019); however, the canonical lichen symbiosis features an interdependent relationship between a fungus and a photobiont in which the photobiont provides energy from photosynthesis and the fungus provides protection and nutrients (Nash Reference Nash2008). Similar to the example of archaea and fermenting bacteria, the lichen can survive and persist in environments that would challenge its constituent members in isolation (de la Torre et al. Reference de la Torre, Sancho, Horneck, de los Ríos, Wierzchos, Olsson-Francis, Cockell, Rettberg, Berger and de Vera2010).

The interdependent relationship found in microbial syntrophies and lichens produces a group phenotype in which the whole is more than a sum of its parts. A distinction between a group phenotype and the phenotype of its constituent parts is prevalent in studies of multicellularity (Okasha Reference Okasha2006) where it provides contrast between a population of cells and a multicellular group of cells (Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2009). For lichens, one key emergent group phenotype is a macroscale thallus structure that facilitates the symbiosis (Honegger Reference Honegger1998; Nash Reference Nash2008). Neither the photobiont nor the mycobiont builds it without the other. Its large scale also leads other organisms to interact with the lichen as a whole differently than they would either constituent organism; for example reindeer graze on lichens but not on isolated populations of mycobionts or photobionts. For microbial syntrophies, the group phenotype is represented by its growth or survival in different metabolic environments. In both cases a division of labour gives rise to a group phenotype in which changes in cell traits can modify the group phenotype. For example, if one species in a syntrophy has a loss of function mutation inhibiting its production of a certain metabolite, then the syntrophy can collapse (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Niehus and Foster2014; Kallus et al. Reference Kallus, Miller and Libby2017). Thus, there is the potential for group phenotypes to evolve in response to cellular mutations and possibly adapt.

A central challenge that determines whether a community can act as a higher-level of selection is whether it can replicate, that is whether groups can reproduce. This challenge is particularly pertinent for multi-species communities such as lichens or microbial syntrophies because, in order for the group to reproduce, at least one cell of each species should be present in the group's ‘offspring’ (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Niehus and Foster2014; Estrela et al. Reference Estrela, Kerr and Morris2016; Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2016). In general, there seem to be two main categories of solution to this problem: groups can reproduce through fragmentation or through a process of dispersal and reassembly. With fragmentation, a part of the group breaks off from the original group and is able to grow and reproduce similar to the parent (Highsmith Reference Highsmith1982). In snowflake yeast this occurs naturally because of the fractal nature of the growth form. For multi-species communities, as long as a group splits in such a way that both fragments contain the necessary species, then this mode of reproduction should allow for group reproduction. This mode of reproduction is a common form of asexual propagation in lichens (Bowler & Rundel Reference Bowler and Rundel1975) and may occur in microbial syntrophies, though it is difficult to verify in natural populations. The second form of group reproduction involves a dissociation between some cells in the multi-species community and a re-establishment of the relationship elsewhere. In lichens, this typically occurs through the production of fungal spores that are released from the lichen and re-associate with free-living photobionts. For microbial syntrophies, a similar life cycle has been proposed through a process of random dispersal into new habitats (Cremer et al. Reference Cremer, Melbinger and Frey2012; Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Niehus and Foster2014). In both cases the cells that leave the original group and re-establish a new group must contain in their genome traits for perpetuating the interdependent relationship and the emergent group phenotype.

Although lichens and microbial syntrophies may function as units of selection, they differ from a fully-fledged multicellular organism and even the primitive multicellularity exhibited by current experimental systems such as snowflake yeast. The differences between these systems reflect variations in their ‘organismality’, a term highlighting the ambiguity in the definition of an organism (Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2009). Biology has terms that are often used heuristically without precise, universally accepted definitions, such as the concept of ‘species’ (Hey Reference Hey2001) or ‘fitness’ (Ariew & Lewontin Reference Ariew and Lewontin2004). The study of major evolutionary transitions, such as multicellularity, in particular depends on how we define ‘organisms’. A central concept to emerge from philosophers studying biological individuality is that whether an entity is an organism is not binary, but rather lies on a spectrum (Godfrey-Smith Reference Godfrey-Smith2009; Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2009). For example, Queller & Strassmann (Reference Queller and Strassmann2009) mapped groups of two species in terms of cooperation and cellular conflict and determined a lichen to be more organismal than a system of squid and its Vibrio fischeri, and less organismal than the system of a eukaryotic cell and its mitochondria. The same axes were also used to relate different types of multi-celled populations and multicellular populations. It is likely that some transitions from unicellularity to multicellularity will appear to be rapid and unambiguous, resulting in an entity that is much more organismal than its ancestors within a single generation, while other transitions may never have an easily identifiable moment of transition. For example, the evolution of snowflake yeast has a distinct transition arising from a single causal mutation in which a well-defined group emerges from a unicellular ancestor. In contrast, a microbial syntrophy may always appear as a hybrid between a form of sociality and something organismal, stuck between the two evolutionary states of uni- and multi-cellularity. We assume that the type of multicellularity that evolves from a collection of two unicellular species (e.g. a form resembling a microbial syntrophy or the lichen symbiosis) may be a higher-level unit just not to the same degree as a plant or animal. Importantly, we do not argue that lichens or microbial syntrophies are multicellular organisms but rather they can serve as models to inform our understanding of the evolution of multicellularity.

Evolutionary Origins

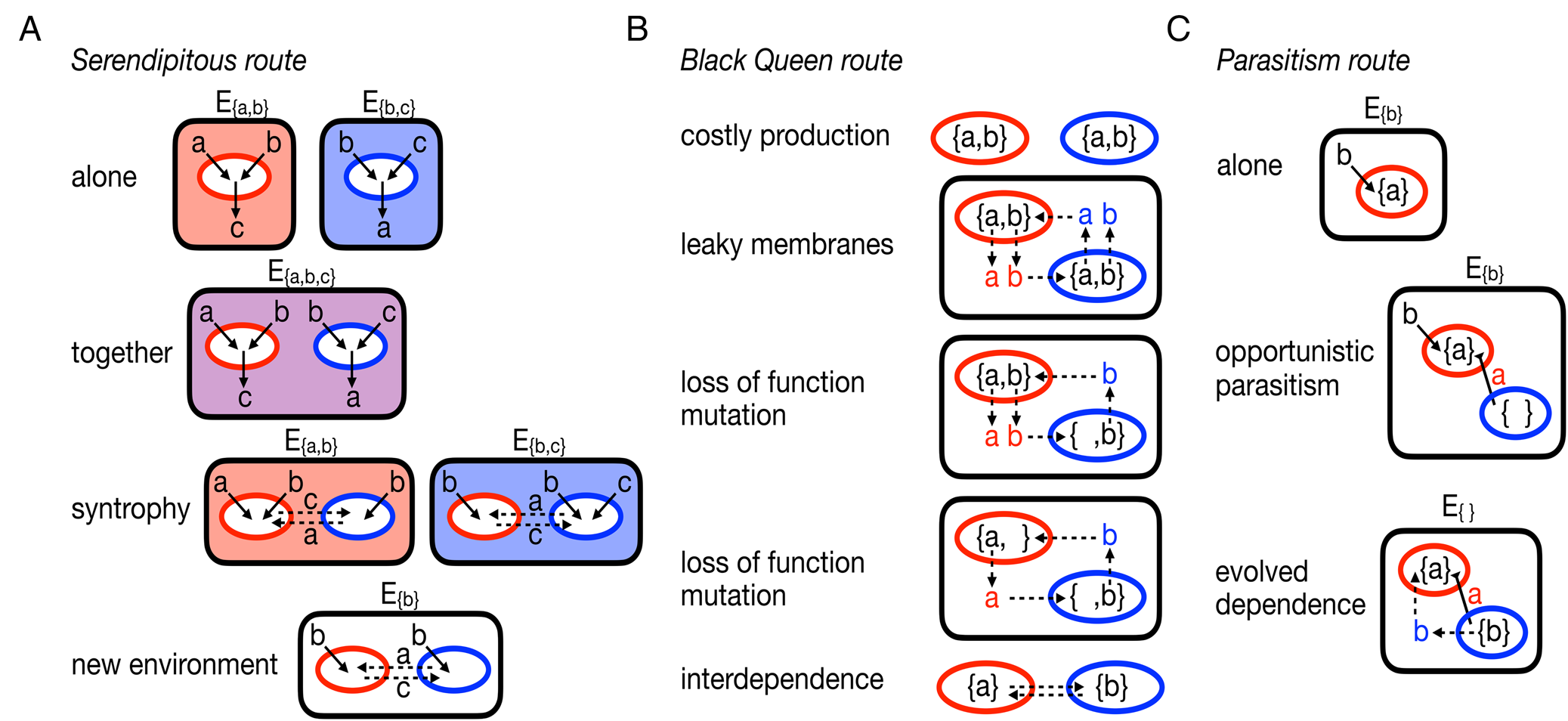

If we use microbial syntrophies and lichens as guides to understanding how multicellularity might evolve from a collection of unicellular species, then it is necessary to consider how a collection of cells might evolve an interdependent relationship capable of evolving group-level adaptations. One simple possibility is serendipity: two originally self-reliant cells somehow end up in an environment in which neither can survive on their own, but the pair can survive together (see Fig. 2A). The pair's survival allows them to colonize new, similar environments and propagate the relationship. In this case, it would be difficult to isolate any causal mutation for the interdependent relationship. It might be possible to identify mutations that can disrupt the relationship but its origination is a product of fortuitous complementary evolution. Interestingly, computational work has shown that many microbes, with no known history of interaction, can be paired in environments in which they survive through the exchange of metabolites (Klitgord & Segrè Reference Klitgord and Segrè2010). Metabolic complementarity has also been found in pairings of random, computer-generated metabolisms in the absence of any evolutionary history (Libby et al. Reference Libby, Hébert-Dufresne, Hosseini and Wagner2019). Together, these studies suggest that the serendipitous path to syntrophy (and possibly multicellularity) does not need specific prior adaptations and may be more likely to occur than expected.

Fig. 2. Alternative, egalitarian routes to evolving multicellularity. A, the serendipitous route starts with two organisms (coloured red and blue) capable of surviving in environments that provide them with the necessary metabolites, Ea,b provides metabolites a and b and Eb,c provides metabolites b and c. Each organism produces waste products they do not need, the red organism excretes c and the blue organism excretes a. Should the organisms share an environment, say Ea,b,c, they can then engage in a syntrophy that allows them to survive in environments where one or both could not survive before. B, the Black Queen route begins with two self-sufficient organisms that produce the necessary, yet energetically costly, metabolites a and b. It is assumed that they have some permeability in their membranes such that some of their metabolites diffuse out into the environment and become available to others. The availability of metabolites in the environment allows for mutations to arise in the population that disable the production of metabolites. Ultimately the organisms become reliant on each other: the blue organism needs a from the red and the red needs b from the blue. C, the parasitism route starts with an organism (red) that takes in a product b from the environment and produces a. An opportunistic parasite (blue) arrives and steals a from the red organism. In response to a selective pressure, such as another competing parasite or changing environments or improved growth, the parasite evolves to provide a benefit to the red organism.

An alternative evolutionary path to the type of metabolic interdependence found in syntrophy requires that at least one of the microbes be initially self-reliant and then the mutual dependence is a derived, evolved state (see Fig. 2B). In this scenario, the mutual dependence is usually posited to occur through deleterious mutations that erode metabolic independence but free microbes of the burden of producing costly metabolites (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Lenski and Zinser2012; Hillesland et al. Reference Hillesland, Lim, Flowers, Turkarslan, Pinel, Zane, Elliott, Qin, Wu and Baliga2014; D'Souza & Kost Reference D'Souza and Kost2016). The Black Queen Hypothesis (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Lenski and Zinser2012) extends this scenario to describe how a group of independent cells can evolve into a community in which metabolic functions are partitioned across different, interdependent cells.

Finally, lichens illuminate another way to evolve an interdependent relationship between two species that lies somewhere between the serendipitous and Black Queen paths. We focus on the simplest abstracted form of a lichen that features an interdependent relationship between a fungus and a photobiont; many modern lichens have other partners (Grube & Berg Reference Grube and Berg2009; Spribille et al. Reference Spribille, Tuovinen, Resl, Vanderpool, Wolinski, Aime, Schneider, Stabentheiner, Toome-Heller and Thor2016), but these were probably later additions following evolution of the initial pairwise relationship. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that the initial relationship of the fungus and photobiont could have ranged from mutualistic to parasitic (Gargas et al. Reference Gargas, DePriest, Grube and Tehler1995). Experiments co-culturing a fungus and photobiont have also shown that a mutualistic relationship may have occurred serendipitously due to a simple change in the environment (Hom & Murray Reference Hom and Murray2014). Here, we consider an initial parasitic relationship because it is a novel starting state for studies of the evolution of multicellularity. Although the relationship between fungi and their photobionts seems to be fluid, with the potential to evolve between parasitism and mutualism (Gargas et al. Reference Gargas, DePriest, Grube and Tehler1995; Lutzoni et al. Reference Lutzoni, Pagel and Reeb2001), there is a lack of experimental or observational data on the mechanisms or conditions that allow this to occur. Instead, we draw insights from recent experimental systems using bacteria and phages (Poullain et al. Reference Poullain, Gandon, Brockhurst, Buckling and Hochberg2008; Shapiro & Turner Reference Shapiro and Turner2018) and outline a possible path from parasitism to an interdependent relationship, for example lichen symbiosis (see Fig. 2C).

At the start the interaction would not have been interdependent, the fungus would simply be an opportunistic parasite of the photobiont. From there it could evolve along two basic lines: i) the fungus could remain opportunistically parasitic of the photobiont, or ii) it could evolve a more specialized parasitic relationship (i.e. increase its host specificity). In the first case, the interaction between the two would remain transient; by contrast, the second case could lead to more sustained interactions. If the fungus evolved to preferentially parasitize the photobiont then mutations that increased the likelihood of interactions between the two would be selected for in fungal populations; note the process could also happen in reverse whereby more frequent interactions between the two species promote fungal populations to evolve a more specialized parasitic relationship. Either case would lead to repeated interactions between fungi and photobionts and thus perpetuate the parasitism across future generations. By evolving ways to perpetuate interactions with the photobiont, the fungus effectively evolves a form of group reproduction, ensuring propagation of fungus-photobiont groups. At this point, the fungus need not provide any benefit to the photobiont and the relationship could always be one of parasitism. Yet, depending on the environmental conditions affecting the life history of fungus-photobiont groups, there could be selective pressure for the fungus to evolve restraint or invest in the growth of the photobiont to ensure successful transmission/reproduction, similar to other host-parasite relationships (Kochin et al. Reference Kochin, Bull and Antia2010). If this were to occur, then it would facilitate the accumulation of mutations that regulate their interactions, producing more long-lived lichens that feature interdependent relationships, if only transiently.

Pathway Features and Challenges

In the previous section, we considered a set of paths to multicellularity starting with a group of different species that evolves an interdependent relationship and a way of propagating or transmitting that relationship across generations. The paths differ in terms of when and how co-transmission and interdependence evolve, causing them to face unique challenges. For example, in the serendipitous path the interdependent relationship between species is present at the start but co-transmission of the two species must evolve for there to be some form of reliable group reproduction. In contrast, the parasitic path may start with some form of co-transmission, assuming that the parasite is successful, and then interdependence must evolve for the relationship to be cooperative and more like a multicellular organism. Despite the variation among paths, they share characteristic features that differ with current experimental and theoretical models of the evolution of multicellularity.

A key area of difference between the novel paths to multicellularity and currently studied paths is the structure of groups. In models where multicellularity evolves from a single species, called a ‘fraternal’ transition (Queller Reference Queller1997), the formation of groups usually involves a physical process of staying together (Tarnita et al. Reference Tarnita, Taubes and Nowak2013) that creates well-defined, clonal groups. For example, in snowflake yeast cells remain together following reproduction so groups are a connected set of cells, and in P. fluorescens cells produce an extracellular glue and stick to their offspring. In contrast, the novel paths to multicellularity described above have a group structure that is defined by interdependent relationships. Species are not necessarily physically connected by a glue or membrane but rather by the functional reliance on each other. Certainly they can evolve physical connectedness, for example a lichen thallus, but at the onset it is not strictly necessary and it may never evolve (Queller & Strassmann Reference Queller and Strassmann2016).

The lack of a connected group structure in the novel paths to multicellularity can make groups permeable so that members might leave and others might join. While some permeability is necessary for groups to reproduce (either via fragmentation or dispersal/reassembly), it also allows for new organisms, not originally part of the group, to invade and possibly alter existing relationships. The outcome of invasion and population mixing is likely to vary depending on the context, but studies of the evolution of microbial cooperation have shown that well-mixed, fluid environments can promote the rise of evolutionary cheats that disrupt cooperative relationships (Nadell et al. Reference Nadell, Drescher and Foster2016). However, there is also evidence that some interdependent metabolic relationships can be maintained and withstand invasion from cheating types (Pande et al. Reference Pande, Merker, Bohl, Reichelt, Schuster, de Figueiredo, Kaleta and Kost2014). If we turn to lichens, which have more physical structure than most microbial syntrophies, there is a large class of lichenicolous fungi which parasitizes existing lichen symbioses and sometimes steals photobionts (Richardson Reference Richardson1999; Nash Reference Nash2008). However, invasions can also lead to novel forms of cooperation. For example, some lichens are found to be a symbiosis made up of three partners which suggests other partners can become integrated into the group (Spribille et al. Reference Spribille, Tuovinen, Resl, Vanderpool, Wolinski, Aime, Schneider, Stabentheiner, Toome-Heller and Thor2016; Tuovinen et al. Reference Tuovinen, Ekman, Thor, Vanderpool, Spribille and Johannesson2019). A similar process would probably be more difficult in snowflake yeast and Pseudomonas fluorescens because they reproduce groups through single-cell bottlenecks which would inhibit transmission of any invaders to future generations.

A salient feature of these novel routes to multicellularity is their division of labour. In all of the novel routes division of labour is present either at the start or within the first mutation; group structure relies on the interdependence that comes from division of labour. Moreover, groups benefit from being able to draw upon the functional complexity and evolutionary history of different genomes. In contrast, current model systems for multicellularity may not necessarily exhibit any division of labour. For example, snowflake yeast are clonal groups with all cells initially expressing a similar phenotype. Evolving division of labour would be a later, possible group-level adaptation and a step towards greater multicellular complexity. The case is different for Pseudomonas fluorescens because division of labour between the mat-forming wrinkly types and the free-living smooth types is essential for group reproduction. The problem is that it relies on a ready supply of mutations to switch back and forth and experimental evidence suggests that such mutations may be increasingly less available over many life cycles (McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Gehrig, Meintjes, Zhang and Rainey2009; Lind et al. Reference Lind, Farr and Rainey2015). Certainly, organisms can circumvent this mutational supply problem by evolving epigenetic ways of dividing labour such as a phenotypic switch or regulation (Libby & Rainey Reference Libby and Rainey2013b; Gallie et al. Reference Gallie, Libby, Bertels, Remigi, Jendresen, Ferguson, Desprat, Buffing, Sauer and Beaumont2015), but it requires multiple iterations of the life cycle to fix in a population. This highlights a difficulty with evolving division of labour in clonal experimental systems: it requires mutations that cause temporal or spatial phenotypic differentiation. In contrast, egalitarian routes to multicellularity capitalize on phenotypic differences between cells, leveraging the benefits of cellular differentiation as an initial driver of multicellular evolution.

Finally, we consider a central challenge in the egalitarian routes to multicellularity: reproduction. In either the fragmentation or the dispersal/reassembly mode of reproduction, two species must ensure that their relationship persists in order to propagate the nascent multicellular organism. The more interdependence among the species, that is the cells of the nascent multicellular organism, the more essential it is to ensure that they co-transmit. Work by Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Niehus and Foster2014) showed that uncertainty in co-transmitting with a syntrophic partner can limit the evolution of metabolic interdependence. Without a way of ensuring co-transmission, species must balance between specificity and generality; greater specificity could lead to greater mutual gains from a partnership but at the cost of lower survival in its absence. One way to navigate uncertainty in co-transmission while not being completely self-reliant is for species to evolve reliance but not on specific partner species, a form of general dependence but not specific interdependence. Indeed, there is evidence that metabolism in bacteria is a property of a community of bacteria, partitioned across potentially many different species (D'Souza et al. Reference D'Souza, Shitut, Preussger, Yousif, Waschina and Kost2018). Yet despite the challenge of co-transmission, lineages of lichens have found ways to reliably reproduce using a dispersal/reassembly life cycle (Nash Reference Nash2008) and maintain specificity in their relationships (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Friedl and Rambold1998). The ways in which they succeed might better inform our understanding of how different species can evolve to form higher-level individuals.

Conclusion

The recent development of experimental systems for studying the origins of multicellularity have shaped our understanding of an important major transition in evolution. Yet, these systems do not capture a class of evolutionary routes to multicellularity that are characterized by the gradual evolution of increased interdependence between initially free-living organisms. Lichens and microbial syntrophies highlight diverse routes to egalitarian multicellularity and shed light on the main challenges and possible ways to overcome them. In this regard, lichens, with their unique combination of phylogenetic diversity and extensive life history variation, would make exemplar model systems to extract general principles. Thus, ongoing efforts to better understand lichen evolutionary and natural history may pay unexpected dividends in our understanding of how non-canonical multicellular organisms arise.

Author ORCID

Eric Libby, 0000-0002-6569-5793.