Introduction

One of the reasons that many African countries resisted the inclusion of intellectual property (IP) into the multilateral trade regime was the concern that it might impede access to essential medicines.Footnote 1 Twenty-five years since the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and adoption of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement),Footnote 2 Africa still struggles with issues of access to medicines. While critics argue that IP rights (IPRs) and the minimum standards brought about by the TRIPS Agreement hamper access to medicines for developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs) as they, inter alia, increase the price of medicines, prevent reverse engineering of patented products and delay the entry of generic drugs,Footnote 3 others point to non-IP related issues such as infrastructure, government priorities and corruption as playing a major role in depriving the population of needed medicines.Footnote 4

The TRIPS Agreement introduced minimum standards on substantive and procedural aspects of IPRs applicable to all WTO Members. The Agreement, however, contains several important safeguards and recognises ‘the special needs of the LDC members in respect of maximum flexibility in the domestic implementation of laws and regulation in order to enable them to create a sound and viable technological base’.Footnote 5 Article 1.1 further acknowledges this when stating that Members ‘shall be free to determine the appropriate method of implementing the provisions of this Agreement within their own legal system and practice’. Moreover, through a series of waiver decisions taken by the WTO Members, LDCs have not had to implement and do not have to protect pharmaceutical patents and test data until 2033.Footnote 6

Perhaps the most notable achievement in the post-TRIPS era has been the success of developing countries and LDCs in gaining recognition of the issue and concessions through the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health in 2001. Coming on the back of the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the late-1990s, the Declaration focuses on the potential adverse impact of IP on public healthFootnote 7 and acknowledges that compliance with TRIPS does not and should not prevent Members from adopting public health measures.Footnote 8 In addition, the Declaration further affirms the interpretation and implementation of TRIPS Agreement in a manner that supports Members’ right to protect public health and, in particular, promote access to medicines.Footnote 9 Moreover, the Declaration explicitly acknowledges the difficulties that Members with ‘insufficient or no manufacturing capacities in the pharmaceutical sector’ could face in making use of the compulsory licensing provisions under TRIPS Agreement,Footnote 10 and led to a waiver-turned-amendment allowing for the importation of pharmaceuticals under a compulsory licence.Footnote 11 The impact of the Declaration should not be understated – this was the first time that the WTO collectively and unequivocally acknowledged the potential negative impact of IPRs on access to medicines.

The debate surrounding the impact of IPRs on health has evolved with several public health emergencies. These include the HIV/AIDS epidemic but also other emergencies such as the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa (2014–2016) and the Zika virus in Latin America (2015–2016). The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified these concerns and reignited discussion on the interface between patents and access to medicines. In fact, India and South Africa proposed a waiver of IPRs in order to enhance access to Covid vaccines and therapeutics,Footnote 12 and while supported by a majority of WTO Members,Footnote 13 the negotiations culminated in a Ministerial Decision which is limited to vaccines and more akin to a broadening of the compulsory licensing provision more than a waiver of IPRs.Footnote 14

This paper examines the status of pharmaceutical patent law in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The SADC serves as a useful case study as the region has the highest prevalence of HIV and AIDS,Footnote 15 second highest in MalariaFootnote 16 and primarily relies on generic drugs to treat diseases.Footnote 17 Hence, access to patented vaccines and therapeutics (in terms of both affordability and availability) is a crucial issue to the region. More specifically, the paper surveys seven of the sixteen SADC countries to understand the nature, scope and depth of their laws. The selected countries – Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe – represent a mix of both major and modest economies. These countries are also representative of the region as four are developing countries and three are LDCs. Such a survey is needed, as assertions are often made about the impact and effect of TRIPS on developing countries and LDCs but the actual laws of these countries are rarely considered.

The survey finds that despite the advent of the TRIPS Agreement there have been relatively few changes to the legal regimes of SADC member states. The laws for most of these states date back to colonial-era legislation or remain based on a colonial model – for instance, South Africa's patent law dates to 1978, while others such as Malawi (1986) and Tanzania (1994) maintain pre-TRIPS legislation. This survey reveals that SADC countries are not fully taking advantage of the flexibilities built into the TRIPS Agreement in that these have not yet been transposed into the domestic regimes. This is true even for SADC countries that have relatively recently amended their legislation. That being the case, another major finding of the survey is that in most of the surveyed countries, few patents and even fewer pharmaceutical patents are filed. If patents are not filed, there is no protection and no domestic impediment to manufacture, importation and distribution. This is not to say, however, that the TRIPS Agreement does not have an effect. To the contrary, patent status in other countries still impacts whether and how easily a SADC country can import pharmaceuticals, as importation can only occur if the product can be legally exported from a third country.

This paper proceeds as follows. Part 1 briefly describes the IP landscape in SADC before examining patents in surveyed SADC countries and the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) with a focus on pharmaceutical patents. Part 2 introduces the relevant flexibilities in the TRIPS Agreement and analyses the domestic laws of the surveyed countries in light of these flexibilities. Part 3 summarises the findings and offers recommendations while the final section provides summaries and conclusions.

1. Intellectual property landscape and patenting trends

Established in 1992 with the primary objective of promoting sustainable and equitable economic growth and socio-economic development among Member States,Footnote 18 SADC is one of the eight Regional Economic Communities recognised by the African Union (AU). SADC has not formulated a regional instrument specifically addressing IPRs. However, all members of SADC are Members of the WTO. In addition, SADC's Protocol on Trade provides for members to adopt IP policies and measures in accordance with the TRIPS Agreement.Footnote 19 SADC has also adopted a Protocol on Health with the principal objective of cooperation and coordination of activities aimed at improving access to health and progressive standardisation of health services in the region.Footnote 20 The Protocol provides for cooperation among parties in the production, procurement and distribution of affordable essential drugs, and the development of mechanisms for quality assurance in the supply and conveyance of vaccines.Footnote 21

All of the surveyed SADC countries, with the exception of South Africa, are members of ARIPO. Founded by the Lusaka Agreement (1976), ARIPO works to strengthen member states’ IP systems. By signing the Lusaka Agreement, ARIPO members agreed ‘to pool their resources to develop an IP system that would support economic, social, scientific, technological, and industrial development’.Footnote 22 A vital component of this process is ARIPO's facilitation of IP cooperation among its 19 members (including 11 LDCs).Footnote 23 ARIPO's Harare Protocol on Patents and Industrial Designs (Harare Protocol) allows patent applications to be submitted to any contracting party or directly to ARIPO.Footnote 24 The Harare Protocol establishes a system enabling patent applicants to indicate which member state they are requesting protection for, and in this regard operates in a similar fashion to the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).Footnote 25

As of October 2019, ARIPO has received only 11,896 patent applications,Footnote 26 8.5% of which come from within Africa and only 2.5% of which are from ARIPO member states.Footnote 27 What is most surprising, however, is that in over 40 years of ARIPO's formation there have only been a few applications for pharmaceutical patents.Footnote 28 Furthermore, a study conducted by the WHO Regional Office for Africa Universal Health Coverage/Life Course Department finds only 3,458 health-related patents registered in ARIPO as of April 2019.Footnote 29 The study also indicates that ARIPO employed a shockingly low number of patent examiners – with only six in total.Footnote 30

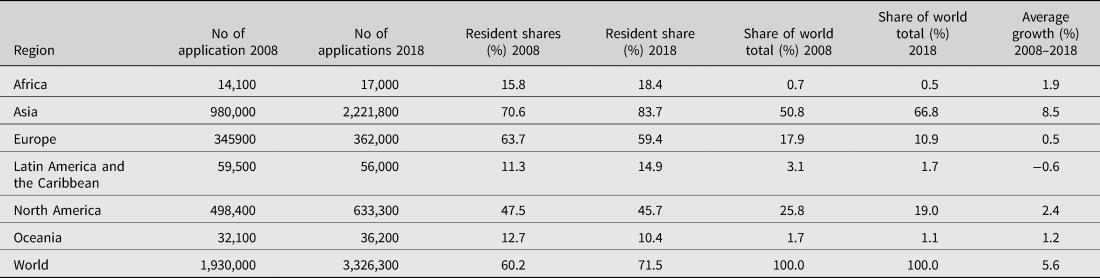

Based on the analysis of the countries of origin filing health-related patents at ARIPO, South Africa is the only African country to make the top 10. What is perhaps more striking is that Kenya, Mauritius, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Egypt are the only other African countries with any health-related patent applications. Broadly speaking, the data available in Table 2 indicates that Africa in general only accounted for 0.5% of the total patent applications filed worldwide in 2018. Table 1 is more specific and indicates the number of patents filed in the studied countries in 2020.

Table 1: Patent application by office 2020

Source: Author tabulation from WIPO and ARIPO statistics databases.Footnote 31

Table 2: Patent applications by region, 2008 and 2018

Note: Totals by geographical region are WIPO estimates using data covering 160 offices. Each region includes the following number of offices: Africa (32), Asia (45), Europe (45), Latin America and the Caribbean (32), North America (2) and Oceania (4).

Source: WIPO Statistics Database, August 2019.

With data being notoriously difficult to obtain in Africa, the figures captured in Tables 1 and 2 may not be an entirely accurate representation of patents in the jurisdictions, but they nevertheless lend credence and support the low patenting trend which has been well-established in the literature.Footnote 32 This low patenting trend indicates that there are many other factors responsible for the paucity of pharmaceuticals in African countries other than patent protection. That being said, the SADC countries should nevertheless focus attention on IP-related issues affecting the availability of essential pharmaceuticals. As discussed below, this includes making better use of flexibilities available in the TRIPS Agreement – including those that are not necessarily dependent on whether patents are in force in a jurisdiction.

ARIPO has been criticised for promoting an IP maximalist agenda. For instance, a survey conducted in 2014 concluded that the East African Community (EAC) has been constrained in its ability to fully utilise the TRIPS flexibilities due to the workings of ARIPO.Footnote 33 The study found that ARIPO places barriers to the importation and local production of affordable pharmaceuticals by failing to encourage and facilitate full use of TRIPS exceptions.Footnote 34 Health activist Brook K Baker also criticised the ARIPO-commissioned ‘Comparative Study of the Industrial Property Laws of ARIPO Member States’ (Comparative Study) for failing to take into account the vast majority of TRIPS flexibilities available to its members.Footnote 35 More specifically, Baker criticised the study for:

lack[ing] of substantive discussion on stringent patentability standards; a range of allowable non-inventions and exclusions; on research and education, as well as other exceptions permitted under TRIPS Article 30; disclosure requirements; the prerogative of governments to define the grounds for compulsory licences; and the use of competition policy to address abuse of patents.Footnote 36

Rule 7(3) of the Harare Protocol regulation is a clear example of a TRIPS-plus provision which may not be suitable for the region in that it allows claims ‘relating to second uses of known and already patented pharmaceutical products’. At the same time, one can question the actual real-world impact of the Protocol. For instance, while second-use patents are said to encourage frivolous patent applications and evergreening, given the low levels of patent applications in the region the claim does not stand for ARIPO member states as rarely is there even a patent on the first use. That is to say, despite the existence of a TRIPS-Plus provision that is known to encourage the filing of frivolous patents and evergreening elsewhere, it did not have this effect in ARIPO member states.

This is not to say that impactful reforms could not be made. Here, Baker proposes reforms that could maximise member states’ policy space to enhance access to affordable medicines. More specifically, Baker recommends that ARIPO member states should: (1) consider adopting both pre- and post-grant opposition systems; (2) adopt international exhaustion rules and easy procedures for parallel importation; (3) adopt remuneration guidelines to simplify the process of issuing compulsory and government-use licences; (4) simplify procedures for the use of Article 31bis when utilised either as a producer/exporter or as a user/importer; and (5) retain the right to issue compulsory licences on the grounds that the patent is not worked locally.Footnote 37 Baker's analysis and findings are relevant to and in line with the crux of this paper, which centres on the need for the surveyed countries to take action to ensure they can benefit from TRIPS flexibilities.

2. TRIPS flexibilities and SADC countries

TRIPS flexibilities refer to provisions within the TRIPS Agreement providing policy space for WTO Members to calibrate their domestic IP regimes.Footnote 38 In this regard, the TRIPS Agreement provides Members with scope to interpret certain provisions in line with their needs, priority and health objectives.Footnote 39 Of course, the fact that flexibilities exist in the TRIPS Agreement is only half the story – the degree to which these flexibilities are incorporated into domestic legislation determine the precise scope available to countries seeking to protect legitimate domestic interests.Footnote 40 The built-in flexibilities allow developing countries and LDCs space to tailor patent legislation to their own developmental needs, but cannot be of assistance if Members do not provide for their applicability in domestic legislation or guidelines.

Before continuing, we must acknowledge that the lack of action in implementing flexibilities is not always down to neglect or indifference but rather due to pressure (both political and technical) exerted by certain developed countries and the innovative pharmaceutical industry. This pressure, which could be in the form of a subtle public relations campaign or direct threat of reduced aid or availability of certain pharmaceuticals, attempts to coerce developing countries and LDCs into modifying, strengthening and/or adopting/repealing measures and discourages the adoption and exploitation of TRIPS-compliant flexibilities.Footnote 41

It nevertheless remains worthwhile and important to canvass and assess the utilisation of flexibilities in developing countries and LDCs. While TRIPS flexibilities have been extensively discussed in academic discourse at a general level,Footnote 42 there have been few attempts to examine whether countries have effectively utilised them in their domestic legislation and policies. This is particularly the case in Africa. This section reviews various types of flexibilities and their application in the selected SADC countries: (1) transition periods; (2) standards of patentability; (3) parallel importation; (4) compulsory licensing; (5) test data exclusivity; and (6) regulatory review exception.

(a) Transition periods

The TRIPS Agreement requires that Members provide patent protection to both products and processes for a minimum of 20 years from the application filing date.Footnote 43 However, the Agreement provides Members with a transition period for implementation.Footnote 44 While developed countries had to comply with TRIPS within one year of it coming into force, developing countries and economies in transition from central planning were granted a transition period to 1 January 2000.Footnote 45 Acknowledging the economic, financial, and administrative constraints of LDCs, the TRIPS Agreement initially allowed for an 11-year transition, until 2006. This period was extended until 1 July 2013, then again until 1 July 2021 and most recently until 1 July 2034.Footnote 46 With respect to pharmaceuticals, the Doha Declaration exempted LDCs from complying with Sections 5 (Patents) and 7 (Protection of Undisclosed Information) of the TRIPS Agreement until 2016.Footnote 47 The waiver has been extended until 1 January 2033.Footnote 48

Three of the selected SADC countries – Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia – are LDCs and therefore enjoy the extended transition periods.Footnote 49 None of these countries, however, takes full advantage of the extension. This is not to imply that the countries are in compliance with TRIPS – there are anomalies. In fact, only Zambia provides for a protection period of 20 years from the filing date of the patent application.Footnote 50 In contrast, Malawi provides a term of protection of 16 years from the date of filing (with the possibility of an extension of between 5–10 years),Footnote 51 while Tanzania provides a period of protection of 10 years from the date of filing, with the possibility of a five-year extension for inventions being worked in the country or legitimate reasons why the patent is not being worked in the country.Footnote 52

Moreover, and despite the existence of a specific WTO waiver for pharmaceuticals, the LDCs do not exclude pharmaceutical products or processes from patentability. The closest any of the covered SADC LDCs get to an exclusion is section 13 of the Tanzanian Patents Act, which provides for the temporary exclusion from patentability for any product by way of statutory instrument. This broadly drafted exclusion, however, has never been applied to pharmaceuticals.

(b) Standards of patentability

The principal rule of patentability is that patents must be available to products or processes in all fields of technology provided that they fulfill the patentability requirements of novelty, inventive step (non-obviousness) and industrial application (usefulness).Footnote 53 However, the patentability requirements are not substantively defined under any international framework, including the TRIPS Agreement. Members have leeway to flexibly interpret the criteria in their domestic legislation. There are countless ways to narrow the scope of patentability in a manner that is consistent with the TRIPS Agreement. Several countries adopt such an approach to promote local industry and enhance the availability of inexpensive medicines.Footnote 54 In particular, countries can legislate for substantive examination of patent applications that exclude patents for minor developments and those that place undue limitations on legitimate competition.Footnote 55 In addition, countries can assess ‘novelty’ using expansive definitions of prior art to include everything disclosed to the public and to assess ‘inventive step’ in light of non-obviousness to a person ‘highly’ skilled in the art.Footnote 56 We now review each of the three criterion leading to an invention in turn.

(i) Novelty

The first criterion is novelty – countries must protect inventions that are new, which refers to a subject matter that does not form part of the prior (or existing) art. However, there is no universally agreed definition of what constitutes prior art. Thus, countries must develop interpretive criteria within their system in a manner that is consistent with domestic policy goals and avoids infringing the international standard. An overly liberal interpretation could grant patents to products for which the active ingredient is already known. This, in turn, provides monopoly rights for a product that could otherwise be manufactured as a generic.Footnote 57 Most jurisdictions have adopted ‘absolute novelty’, meaning that the invention cannot be known anywhere in the world before the patent application or priority filing date. India, in particular, has adopted a rigorous standard of novelty requiring that the invention ‘has not been anticipated by publication in any document or used anywhere in the world’.Footnote 58 An alternative to ‘absolute novelty’ is a ‘relative standard’, which defines prior art in terms of the use and knowledge of the invention in a particular jurisdiction only. In the latter case, novelty means that the invention is not known or used in a specific jurisdiction.

With respect to surveyed SADC countries, Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia define the state of the art as anything disclosed anywhere in the world.Footnote 59 Malawi and Zimbabwe, however, adopt a relative standard and thus the state of the art is limited to anything disclosed in their respective jurisdiction.Footnote 60

Moreover, a crucial part of the novelty assessment for pharmaceutical products is the scope of ‘use’ of the invention. First, second and subsequent medical uses and second nonmedical use of a product can be interpreted differently when it comes to the grant of patents. Some jurisdictions opt to protect second and subsequent medical uses if it is deemed new as a spur to follow-up innovation, while others opt against protecting such uses with a view of preventing ‘evergreening’ and promoting access to the product.Footnote 61 Developing countries are often advised to avoid protecting ‘new uses’ of existing products to enhance access to medicines.Footnote 62

With respect to the selected SADC countries, Namibia and Zambia explicitly provide for exclusions from patentability on the ground of new uses of known products, including pharmaceutical products. For instance, Namibia's Industrial Property Act provides that patents are available for inventions that are new, involve inventive step and are industrially applicable but excludes ‘new uses’ of known products (including pharmaceuticals):

New uses, methods of use, forms, properties of a known product or substance and already used for specific purposes … except where the qualities of the subject matter are essentially altered or where its use solves a technical problem that did not previously have an equivalent solution.Footnote 63

Zambia likewise provides for the grant of patent for an invention that is new, involves an inventive step and is capable of industrial application, and explicitly excludes from patentability: ‘New uses of a known product, including the second use of a medicine’.Footnote 64

Malawi and Zimbabwe do not clearly exclude new uses of known products from patentability. However, section 18(c) of the Malawi Patents Act provides that the Registrar may refuse to grant a patent if the application claims as an invention ‘a substance capable of being used as food or medicine which is a mixture of known ingredients possessing only the aggregate of the known properties of the ingredients…’ Section 13(1)(c) of Zimbabwe Patents Act provides for a similar provision. Botswana, South Africa and Tanzania do not provide for the possibility to exclude from patentability new uses of known products, including pharmaceutical products.

SADC countries could do more to ensure that pharmaceutical patents do not hamper access to medicines by explicitly legislating for a higher standard of novelty to exclude inventions that lack genuine novelty from patentability. This could be done by tailoring patent laws using a similar approach to that of India, but another mechanism could be the adoption of the ‘prior consent’ approach. This approach is utilised in Brazil, where patent applications need to seek prior approval from the National Health Surveillance Agency to determine if the patent will endanger public health or create barriers to access to medicines.Footnote 65

(ii) Inventive step (non-obviousness)

The second criterion of patentability is inventive step (non-obviousness). Inventiveness is crucial to patentability because lower standards of non-obviousness allow companies to gain monopoly power over minor improvements that could, in turn, stifle innovation and competition. Similarly, a higher standard of inventiveness could discourage innovation as the failure to receive protection would deter investment into research and development (R&D). That being the case, non-obviousness is not straightforward, as inventions in different fields of technology require different technical assessments. Most jurisdictions find that the standard is met when the invention is not obvious to a hypothetical person with ordinary skill in the art before the filing or priority date. Other jurisdictions, however, adopt an ‘average person’ standard which refers to a person possessing a common general knowledge in the art.

Despite the ‘differences’ in standards, non-obviousness always involves a complex technical assessment that includes the ability and knowledge of the person, existing public knowledge and access to relevant information. The answers to these questions could also differ across fields of technology. Thus, there is ample room for differentiation across jurisdictions. The primary consideration should be to establish a framework that encourages innovation while ensuring public access to technology. In addition, some patent advocates champion assessing inventive step on the social value of the innovation instead of solely by technical assessment. In this regard, in addition to being non-obvious, an invention must also provide sufficient social value to justify patent protection.Footnote 66 When it comes to pharmaceutical products, the recommended policy option for developing countries and LDCs is to apply a strict standard of inventiveness that only protects genuine innovation and prevent unwarranted limitations to competition and access to existing drugs.Footnote 67 Lower standards of patentability would unnecessarily limit competition at the expense of innovation.

With respect to surveyed SADC countries, South Africa, Tanzania and Namibia assess inventive step with reference to ‘a person skilled in the art’.Footnote 68 Whereas Botswana and Zambia provide that an invention must not be obvious to ‘a person ordinarily skilled in the art’.Footnote 69 Malawi's Patent Act contains a unique standard providing that an invention shall receive no patent protection if ‘… the invention is obvious in that it involves no inventive step having regard to what was common knowledge in the art at the effective date of application’.Footnote 70 Curiously, Zimbabwe's Patent Act does not provide for any definition of inventive step thereby leaving it to the patent examiners to make a factual determination on the claimed invention.Footnote 71 Moreover, South Africa recently adopted the first phase of a new IP policy that has the objective of ensuring, inter alia, patentability criteria consistent with its constitutional obligations, development goals, and public policy priorities specifically public health concerns.Footnote 72 It remains to be seen if the policy will lead to the adoption of a novel approach toward the assessment of patentability requirements.

The practical effects of such varying definitions of inventive step across the surveyed countries remain undetermined as no data exists detailing how these standards are implemented during the examination of patent applications. That being the case, we recommend that the surveyed countries use the inventive step criterion to focus on transposing the space for ‘uses’ of known products at the domestic level. This is especially significant for countries that principally rely on generics and imported pharmaceuticals.

(iii) Industrial application (usefulness)

The third patentability requirement is industrial applicability (usefulness), meaning an invention must be industrially capable of being used in any kind of industry. Most jurisdictions effectively presume that inventions are capable of industrial application. However, the usefulness of pharmaceutical inventions is unique considering the level of R&D that an invention goes through prior to patenting. In this regard, the stage at which a pharmaceutical invention becomes useful occurs well before it is administered to humans.Footnote 73 Thus, it is prudent to determine when to grant protection for a pharmaceutical product that must pass successive clinical trial phases to determine its efficacy and utility.

Looking at the legal framework of the surveyed countries, none of the governing laws provide for a detailed definition of usefulness apart from the requirement that inventions must be capable of being applied in any industry. South Africa and Malawi provide that the invention must be applied in trade or industry or agriculture,Footnote 74 while Botswana provides that an invention is considered to have met the usefulness requirement if it can be used in trade, or in any kind of industry including handicraft, agriculture, fishery and other services.Footnote 75 This is similar to Zambia and Namibia, which define industrial application as being made or used in any industry.Footnote 76 By contrast, Tanzania provides a detailed description of industrial application and considers an invention to be industrially applicable ‘if according to its nature, it can be made or used, in the technological sense in any kind of industry, including agriculture, fishery and services’.Footnote 77

(c) Parallel importation

IP exhaustion underpins the principle that ‘once an IP rights holder sells a product to which its IP rights are attached, the rights embedded in the goods are deemed exhausted and the rights holder can no longer control the redistribution of such branded goods’.Footnote 78 Exhaustion is interrelated to the concept of parallel trade. Parallel importation occurs when the IPRs embedded in the goods have been exhausted; parallel imported goods are not counterfeit but genuine products that have been legally brought onto the market by the rights holder (or licensee) in one territory and subsequently sold to a third party in another country without the consent of the rights holder.Footnote 79 Article 6 of the TRIPS Agreement provides Members with discretion to embrace an exhaustion regime that suits their domestic context (subject to the non-discrimination principles of most-favoured-nation and national treatment). The Doha Declaration also clarified that WTO Members are free to establish their own rules and procedures relating to parallel importation.Footnote 80

Three types of exhaustion regimes exist.Footnote 81 First is national exhaustion, which means IP owners cannot control the exploitation of goods within the domestic market once placed on the market for sale. The second is regional exhaustion, which only allows parallel imports between the members of the regional alliance. This implies that upon the first sale of a product in a regional market, the exclusive rights on the product are deemed exhausted. The third is international exhaustion, which means that the IPRs embedded in a product are exhausted with the first sale in any market across the world.

Botswana,Footnote 82 Zimbabwe,Footnote 83 NamibiaFootnote 84 and ZambiaFootnote 85 provide for international exhaustion. For example, Article 43(1) of Namibia's 2012 Industrial Property Act reads: ‘The following acts do not constitute an infringement of the rights under a patent, namely: a) acts of importation of patented inventions which have been put on the market in any territory or country by the owner of the patent or with his or her authorization’.

It remains unclear whether the South African legal framework, especially the Medicines Act, provides for parallel importation of pharmaceuticals. Section 15C of South Africa's Medicines Act provides broadly that ‘the Minister may prescribe conditions for the supply of more affordable medicines in certain circumstances to protect the health of the public’. Even though this section appears to permit parallel importation of patented medicines, it does not specify whether the doctrine of exhaustion applies nationally or internationally. The Malawian Patent Act similarly does not clearly define the principle of exhaustion of IPRs. Instead, the government relies on the vagueness of section 28, ‘Extent, effect, and form of patent’ to assert that parallel importation is permitted. Section 28.4 outlines a patent holder's rights:

The effect of a patent shall be to grant to the patentee, subject to this Act and the conditions of the patent, full power, sole privilege and authority by himself, his agents and licensees during the term of the patent to make, use, exercise and vend the invention within Malawi in such a manner as to him seems meet, so that he shall have and enjoy the whole profit and advantage accruing by reason of the invention during the terms of the patent.

A closer inspection of the provision shows that the rights to import and export patented goods are not addressed, which means that they are not explicitly covered in the Patents Act. From the standpoint of the well-established legal principle that what is not expressly prohibited is permissible, the provision would appear not to grant any exclusive import or export rights.Footnote 86

In Tanzania, parallel imports of patented inventions are excluded from the legislation as section 36 of the Patents Registration Act provides that a patent owner has the right to prohibit anyone from exploiting the patented invention, including by importing, offering for sale, selling, or using it.

In general, the best approach for the surveyed countries remains an unrestricted international exhaustion regime.Footnote 87 The patent laws must be clear and unequivocal in this regard. The rationale for this recommendation is that these countries are net IP importers dependent on pharmaceutical importation. International exhaustion can benefit by helping facilitate the importation of patented products from the cheapest global market in order to assist in meeting prevailing health needs. As simple as this recommendation is, the parallel importation of pharmaceuticals is controversial and complex. Parallel importation of pharmaceuticals involves many other issues beyond trade, including health policies, consumer protection and medical regulations. National marketing approval for pharmaceutical products, labelling laws, import authorisations and other formalities make use of the flexibility even more complicated in practice.Footnote 88 The ecosystem of parallel trade in pharmaceuticals is beyond the scope of this paper,Footnote 89 but from an IP perspective the international exhaustion regime is a viable way to facilitate access to pharmaceuticals for low-income countries.

(d) Compulsory licence

Compulsory licensing could be used for many purposes, including combating anti-competitive behaviour and advancing public health objectives. Compulsory licences can also be granted if the rights owner fails to locally ‘work’ the patent – ie failure to make the patented product available either by import or local production. Recognised as a legitimate tool since the Paris Convention (1883), Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement and the subsequent waiver/amendment (in the form of Article 31bis) agreed upon in the wake of the HIV/AIDS pandemic provide the basis for compulsory licensing in the TRIPS Agreement. In essence, a compulsory licence serves as a ‘safeguard’, allowing a government to respond to any national security or health crisis and safeguard the public from possible abuses owing to IPRs.Footnote 90 While certain scholars and activists advocate for greater use of compulsory licencing in less-developed countries to drive pharmaceutical access,Footnote 91 others warn that ‘the mechanism is not a panacea’ or first-best option to increase access to pharmaceuticals.Footnote 92

All of the surveyed countries allow for compulsory licensing for a variety of reasons, including public interest, failure to licence on reasonable terms and in order to combat anti-competitive behaviour. All of the surveyed countries also provide that a compulsory licence may be issued if the invention, though capable of being worked in the country, is not being worked on a commercial scale and there is no satisfactory reason for non-working.Footnote 93 The legality of local working requirements – domestic provisions which allow the grant of a compulsory licence when a patent is not ‘worked’ in that country – are questionable under Article 27 of the TRIPS Agreement, which prohibits discrimination as to ‘whether products are imported or locally produced’.Footnote 94 The consistency of the provision has never been tested in dispute settlement, however, and there is no evidence that WTO Members maintaining local working requirements are concerned about any inconsistency with the TRIPS Agreement.

Compulsory licences have proven to be an effective tool in reducing the cost of pharmaceuticals. In fact, a recent study conducted by renowned public health advocate Ellen t'Hoen and others concludes that TRIPS flexibilities, and in particular compulsory licences ‘have been used more often than previously assumed’ when procuring generic versions of essential medicines.Footnote 95 In total, the study identified 176 occurrences of possible use of TRIPS flexibilities by 89 countries, of which around 60% engaged in the use of compulsory or government use licences.Footnote 96 Malaysia and Thailand are two examples of countries effectively making use of compulsory licences, with the former reducing the prices of anti-retroviral drugs by 83% in 2002 and Thailand reducing the prices of cancer, coronary disease and HIV/AIDS drugs by 98% through compulsory licences issued between 2006 and 2008.Footnote 97

These countries, however, faced political pressure and even industry reprisals for the issuance of compulsory licences.Footnote 98 For example, the United States (US) considered Thailand's issuance of compulsory licences in 2006-2008 inappropriate and the US Trade Representative (USTR) placed Thailand on the Priority Watch List under Special 301 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 in 2007.Footnote 99 Likewise, the US placed Ecuador on USTR's Special 301 list in 2010 and 2011 owing to its compulsory licensing of pharmaceutical and agricultural chemicals.Footnote 100 Similarly, Merck & Co strongly condemned Brazil following its compulsory licensing of Efavirenz (a drug used to treat HIV) after negotiations for a voluntary licence failed,Footnote 101 calling Brazil's action an ‘expropriation of intellectual property [that] sends a chilling signal to research-based companies about the attractiveness of undertaking risky research on diseases that affect the developing world’.Footnote 102 These are but a few examples of the pressure faced by countries seeking to make use of TRIPS-compliant flexibilities and issue a compulsory licence.

Countries with insufficient or no manufacturing capabilities face additional hurdles. The TRIPS amendment resulting in the creation of Article 31bis – popularly called the ‘Doha Paragraph 6 Solution’ – establishes a procedure for countries with insufficient or no local manufacturing capacity to import under a compulsory licence. Some commentators, however, assert that inefficiencies and bottlenecks associated with the system make it ineffective if not irrelevant.Footnote 103 As evidence, these critics point to the procedural difficulties encountered in the single case of the system's use involving pharmaceuticals being imported to Rwanda. For instance, part of the three-year time period between Rwanda's indication to use the system and supply featured a lengthy voluntary licence negotiation between Canada's Access to Medicines Regime and the three Canadian companies holding patents on the pharmaceutical product in question.Footnote 104 In addition, during the same three-year period, Rwanda issued a public tender that saw four Indian generic manufacturers entering into prolonged and ultimately unsuccessful negotiations on supplying the patented medicine.Footnote 105 While these delays are not necessarily caused by the system, they are illustrative of the fact that the procedural requirements can delay supply.Footnote 106

These issues notwithstanding, in practice it is often the threat to issue a compulsory licence (as opposed to the actual use) that serves an important purpose as it is a key bargaining chip for countries negotiating purchases from pharmaceutical companies.Footnote 107 In this regard, we disagree with the critics and contend that the system has served its purpose in reducing prices and increasing access such that developing countries and LDCs have not proclaimed the need to actually use the system in recent years. It is for this reason that it has been reported that African countries strongly supported the adoption of the recent Ministerial Decision as it would provide for a stronger and even more credible threat to use as leverage in procurement negotiations.Footnote 108 For these reasons, and although imperfect,Footnote 109 the system has undoubtedly played (and will continue to play) a supportive role in the wider effort to improve access to essential medicines and serve as a vital instrument in addressing the conundrum facing countries with little or no pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity.Footnote 110

None of the surveyed countries has explicitly incorporated the provisions of the TRIPS amendment.Footnote 111 While it is technically possible to utilise the system without requiring special domestic legislation – for example, the Philippines merely requires that a compulsory licence ‘shall also contain a provision directing the grantee of the licence to exercise reasonable measures to prevent the re-exportation of the products imported under this provision’Footnote 112 – explicitly providing for the provisions of the amendment would, however, offer a clear and firm basis for use of the system.

It is important to remember that compulsory licensing is not a ‘magic pill’, and ‘it is the threat of a compulsory licence that is a valuable bargaining chip to be used to extract concessions from the rights holder’.Footnote 113 Moreover, a compulsory licence cannot facilitate the transfer of the know-how and technical knowledge needed to exploit complex inventions nor can it drive the market competition needed to reduce the price of pharmaceuticals (being a single market licence) on a large-scale sustainable basis.Footnote 114 Therefore, beyond the text of the legislation on compulsory licences, the surveyed countries could also focus on investigating the possibility to build local or regional pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in order to make better use of the mechanism.

(e) Test data exclusivity

Test data exclusivity refers to the ‘protection of clinical trial data required to be submitted to a regulatory to prove safety and efficacy of a new drug’.Footnote 115 The protection of this data provides market exclusivity outside of patent rights with the aim of preventing generic drug manufacturers from relying on such data in their own applications for a set period of time.Footnote 116 To the innovative pharmaceutical industry, allowing other companies to free-ride and rely on test data provides an unfair advantage because the data is complex and expensive to produce. Critics counter that test data protection restricts the production of generic copies, preventing drug prices from falling due to generic competition and making it more difficult for the disadvantaged to access life-saving drugs.Footnote 117 Critics also assert that test data exclusivity unfairly limits knowledge dispersal which is an inherent reward for granting a patent or intellectual monopoly.Footnote 118 In their view, test data exclusivity is a form of evergreening, which arguably may even restrict the ability of governments to grant a compulsory licence, since data monopolies prevent the marketing of generic products, even if a licence has been granted.Footnote 119

The TRIPS Agreement requires protection of test data submitted to national authorities for approval of drugs for marketing. Article 39(3) of the TRIPS Agreement states:

Members, when requiring, as a condition of approving the marketing of pharmaceutical or of agricultural chemical products which utilize new chemical entities, the submission of undisclosed test or other data, the origination of which involves a considerable effort, shall protect such data against unfair commercial use. In addition, Members shall protect such data against disclosure, except where necessary to protect the public, or unless steps are taken to ensure that the data are protected against unfair commercial use.

Consensus has never been reached on what test data protection means, despite the TRIPS Agreement setting out two distinct obligations: protect data against unfair commercial use and against disclosure.Footnote 120 While it is fairly straightforward for health authorities to prevent disclosure of information, the requirement to prevent ‘unfair commercial use’ is somewhat unclear. There is no clear indication of how protection should be implemented, what its limits are, or how long it should last.Footnote 121

None of the seven surveyed countries provide test data protection. Principally, test data protection is intended to provide the originator companies with enough time to recoup their R&D costs. This justification does not match the context of less-developed countries such as Botswana, Zambia, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania and Malawi. There is no empirical evidence to suggest that test data exclusivity increases FDI in the pharmaceutical sector, but what has been proven is that test data exclusivity results in extended periods of protection for originator drugs which delays generic competition and drives up drug costs.Footnote 122 Hence, countries that are secondary markets for innovation drugs should embrace test data exclusivity with caution – such protection will not benefit local pharmaceutical manufacturers or facilitate access to generics. Countries must also be mindful of the fact that access to test data for the purpose of ensuring safety and efficacy of drugs is integral to consumer safety and public interests. Hence, policies and laws should be couched to ensure the appropriate balance of interests.Footnote 123 If a regime does adopt test data exclusivity, it should ensure the availability of ample safeguards, most notably that test data exclusivity does not impede the use of compulsory licensing.

(f) Regulatory review exception

The regulatory review exception, also referred to as the ‘Bolar Exception’, applies to pharmaceutical products which require regulatory requirements in order to place the products onto the market. For new pharmaceutical products, marketing approval requires three phases of expensive clinical testing. However, the approval procedure for generic pharmaceutical products is much simplified. There is no need to go through the three phases of testing; rather the applicant is only required to submit data proving that the generic product performs similarly (bioequivalence or chemical equivalence) to the innovator drug.Footnote 124 Hence, unless the procedure for granting marketing approval to generic drugs is initiated before the patent expiry of the innovator drug, the approval procedure would delay their entry onto the market. That is, without such exception, the competitor would be prohibited from commencing the regulatory review process to place the product on the market until the patent expires. This would extend the monopoly sales period of the original product well beyond the date of the patent expiry.

The regulatory review exception serves two functions. First, it enables the competitor to seek regulatory approval while the patent is in force thereby facilitating quicker access to competition and thus cheaper medicines. Secondly, it prevents the patent holder of the original product from enjoying a period of de facto monopoly protection in excess of the patent term. Expediting the regulatory approval process and easing market entry also assist in reducing the developmental costs of the product.Footnote 125 Thus, it would be prudent for developing countries and LDCs to make use of the regulatory review exception in order to facilitate generic entry into the market and reduce pharmaceutical expenditures.

With respect to the surveyed countries, however, the regulatory review exception is the least utilised exception in SADC countries. Of the surveyed SADC countries, only South Africa and Zimbabwe provide for regulatory review exception. South Africa amended its patent legislation in 2003 to incorporate the exception:

It shall not be an act of infringement to make, use, exercise, offer to dispose of, dispose of or import a patented invention on a non-commercial scale and solely for the purposes reasonably related to the obtaining, development and submission of information required under the law that regulates the manufacture, production, distribution, use or sale of any product.Footnote 126

This exception is not limited to pharmaceutical products. However, in a statement to the WTO in 2018, South Africa reiterated that the amendment was made to expedite the availability of generic medicine on the market.Footnote 127 Similarly, section 24B of Zimbabwe's Patent Law provides that test batches of a patented pharmaceutical product may be produced without the consent of the patent owner six months before the expiry of the patent provided that they are not put on the market before the expiry of the patent.

Given the importance attached to ensuring access to medicine as the primary policy consideration in patent laws of the surveyed countries, it is puzzling that the regulatory review exception is barely used. Studies estimate that 70–90% of drugs consumed in the sub-Saharan African region (which includes all the surveyed countries) are imported.Footnote 128 In this regard, this exception would contribute to alleviating accessibility issues, as generic manufacturers would be able to complete the market approval process prior to the patent expiry and without seeking the consent of the patent holder. The inclusion of the regulatory review exception would therefore facilitate the timely entry of generic competition into the market thus enhancing access to medicines both in terms of availability and affordability.

3. Findings and recommendations

IPRs remain subject to the principle of territoriality and are thus bound in their existence and scope to the territory of the state or supranational entity in which they entered into force or have been recognised. Even though the TRIPS Agreement prescribes uniform minimum standards, in principle, it is for the respective Members to determine the forms of protection deemed appropriate to achieve – or to avoid – effects that are considered (un)desirable for economic, social or cultural reasons. Given that the surveyed countries are net IP importers, it would seem that the best approach would be to ensure that their pharmaceutical patent laws and policies are framed to take full advantage of TRIPS flexibilities.

As demonstrated above, Article 27 on patentability leaves ample room for Members to tailor their laws to meet specific needs and objectives and provide the meaning and scope of each of the criteria for patentability. The recommended approach for the selected countries is therefore to embrace strict rules with patentability that will guard against overprotection and interests that may negate their broader objectives for driving access to affordable medicines. The countries should adopt clear guidelines on the definition of patentability criteria in a manner that extends protection to genuine innovations only while also rewarding investments in R&D. In essence, these countries should adopt similar pharmaceutical patenting approaches to countries such as India and Brazil.

Furthermore, while the availability of compulsory licensing can assist in facilitating access to medicines, the starting point for some countries is to investigate whether it is feasible to develop a pharmaceutical manufacturing in order to harness more effectively the gains of the flexibility. It is also recommended that the surveyed countries should amend their domestic laws to ensure that they can use the TRIPS ‘paragraph 6 solution’ and better prepare for public health emergencies. As noted, the waiver has been available since 2003 but has not been domesticated by any of the countries under study. Furthermore, countries may seek to incorporate a ‘local working’ requirement into their domestic laws, which would provide an easier pathway to facilitate the issuance of a compulsory licence.

Given that the selected countries are pharmaceutical importers, this paper also recommends a broader and more tailored approach to regulatory review exceptions in a manner that will pave the way for generic manufacturers to use a patent to apply for market approval without concerns about infringement claims. It is also recommended with respect to test data exclusivity, that the selected countries should push back against ‘coerced conformity’,Footnote 129 which allows IP maximalist measures to be blindly transplanted into domestic law without considering local priorities or frameworks.

One interesting finding in this paper is the low patenting trend in the surveyed countries and in Africa in general. While the TRIPs Agreement, and pharmaceutical patent protection more generally, have been blamed for the worsening health situation in these countries, the low rate of patenting in Africa generally and in the surveyed countries demonstrates that pharmaceutical patents may not be the chief challenge to pharmaceutical access. Other issues of importance include: pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity; technical and infrastructural capacities for medicines regulation; regulating anti-competitive practices; and pharmaceutical market intelligence. Thus, the main lesson is that while it is important for the surveyed countries take full advantage of the available flexibilities, they must also tackle the non-IP barriers in order to forge a sustainable solution to the challenge of access to medicines.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that the problem of access to essential medicines does not arise solely from the TRIPS Agreement, but denying that TRIPS plays any role in exacerbating the problems is also problematic. That being said, the TRIPS Agreement incorporates safeguards that seek to ensure a balance between the rights and obligations of inventors and users. While safeguards at the international level are necessary, they are insufficient without action at the domestic level. This paper discusses such flexibilities and demonstrates how and why SADC countries should better utilise the safeguards. More specifically, the paper demonstrates how the studied countries have failed to exhaustively utilise the available and calls for them to act. At the same time, the paper warns of the dangers that some TRIPS-plus provisions commonly negotiated into FTAs by certain developed countries may have significant implications on access to medicines. The conclusion is straightforward: countries must ensure that domestic laws maximise flexibilities and avoid enacting measures that impose higher obligations than necessary which could potentially reduce the potency of the flexibilities. While we are not naïve enough to believe that optimal use of TRIPS-flexibilities is a panacea to solving all public health-related problems, we do believe that governments could better play a supportive role in the wider effort to improve access to medicines and overall public health.