Introduction

This article examines a set of refugee-status determination cases decided in the US courts of appeals between 1980 and 2013 and asks why the legal standard for refugee status has proven resistant to settling in the federal courts. The Refugee Act of 1980 requires that an applicant for refugee admissions to the United States demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution on the basis of one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. In the decades since, courts of appeals case law has been characterized by significant, persistent disagreements over the Act's meaning and application. The category of “particular social group” has proven especially difficult for the courts to apply consistently and clearly.

The failure of the courts to settle the meaning of this legal category presents a sociological puzzle. Legal formalism and legal realism, the two foundational approaches to interpreting judicial activity in social science as in law (Posner Reference Posner2008; Tamanaha Reference Tamanaha2009), generate contrasting predictions of how the problem of interpreting problematic statutory categories will play out, but neither captures what the courts have faced with the particular social group category. The baseline expectation of a formalist would be that over time, precedent would narrow the range of possible readings and eventually settle its meaning. Meanwhile, a legal realist would expect language as vague as particular social group to impose few constraints on judges, allowing them to reach their preferred outcomes in cases without needing to assume the effort or risk of elaborating further on the meaning of the statute. Most contemporary realists would expect the interpretive disagreements generally to follow familiar political lines, with left-leaning judges arguing for more inclusive readings and right-leaning judges arguing for more restrictive readings.

In practice, I find judges engaging in repeated close analysis of the phrase particular social group (contra the realist expectation), coupled with a failure to reach settled consensus as to the meaning and application of the term (contra the legalist expectation). Although it is not the focus of this article, in other work I have found that the political composition of the courts of appeals cannot fully account for how sympathetic the courts have been to refugee claims, or for where interpretive disagreements have appeared within and between courts (Owens Reference Owens2017, 113–16, 245–47). While there is overwhelming empirical evidence that judges’ political interests play an important role in determining case outcomes for asylum seekers in the United States (Ramji-Nogales, Schoenholtz, and Schrag Reference Ramji-Nogales, Schoenholtz and Schrag2009), a different explanation is needed to make sense of where and why interpretive disputes over the meaning of the key statutory terms have arisen and remained unsettled.

I use the term “settled law” to refer to agreement among federal judges in their articulations and applications of narrowly defined legal propositions. Correspondingly, “unsettled law” refers to instances of explicit disagreement over clearly defined legal propositions, whether those disagreements appear in the form of dissents from the majority on judging panels, reversals of prior decisions by a court, or splits between two or more circuit courts of appeals. In using these terms, I am drawing on a body of law and society literature that looks at the settling and unsettling of legal concepts in a wide range of empirical settings (Grattet, Jenness, and Curry Reference Grattet and Jenness1998; Phillips and Grattet Reference Phillips and Grattet2000; Jenness and Grattet Reference Jenness and Grattett2001; Halliday and Carruthers Reference Halliday and Carruthers2007; Halliday Reference Halliday2009; Mallard Reference Mallard2014; Halliday and Shaffer Reference Halliday and Shaffer2015). This literature has largely focused on the settling of global and local norms and on legal consciousness, although the work of Phillips and Grattet (Reference Phillips and Grattet2000) is an important exception, focused on the settling of a concept in the federal court system. As Halliday and Shaffer usefully explain the key term, legal principles can be called settled once they have passed through a series of stages beginning with the articulation of a problem and ending with widely shared “understandings of meaning reflected in the practices of officials” (2015, 42). Halliday and Shaffer also stress the recursive nature of the processes that lead to the settling and unsettling of legal norms, with feedback loops between local, national, and (in the case of concepts with transnational application) global developments.

Halliday and his collaborators argue that many context-specific empirical factors bear on whether and when a legal concept becomes settled (e.g., Block-Lieb and Halliday Reference Block-Lieb, Halliday, Halliday and Shaffer2015, 110), and they have duly documented the context-specific contingency across a number of transnational legal orders. There is an important transnational dimension to asylum law,Footnote 1 but here I focus only on one narrow question of statutory interpretation in the US federal courts of appeals. This narrowing of focus allows me to hold constant many of the variables in Halliday and Shaffer's (Reference Halliday and Shaffer2015) conceptual framework—the multiple sites of contestation, institutions, and histories that bear on when and how legal concepts settle—and bring into sharper focus the role of judicial reasoning in settling and perpetuating disputes. The literature on settling, like law and society literature in general, has tended to downplay the significance of law on the books, and I offer here a counter-perspective that legal reasoning and process can explain a great deal about when and where legal concepts settle or remain unsettled. That said, my focus on judicial reasoning as the explanatory factor is not intended to replace, but rather to complement, the social scientific literature that examines refugee law decision making in relation to national and international politics (e.g., Ramji-Nogales, Schoenholtz, and Schrag 2009), administrative state structures (e.g., Hamlin Reference Hamlin2014), and social movement pressures in national or international contexts (e.g., Tazreiter Reference Tazreiter2010).

The remainder of this article is divided into four sections. First, I give a brief overview of the case law coming from the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the administrative agency that reviews asylum claims before they reach the courts of appeals, which has been most important in guiding the interpretation of the term “particular social group.” Second, I outline my case-selection methods and show that disputes over the meaning of particular social group have proliferated across the courts of appeals cases since the passage of the Refugee Act (1980). The next section is a close analysis of the judicial reasoning on display in two “dispute chains”—that is, sets of courts of appeals cases that have disagreed about the statutory meaning of particular social group, and have thereby kept it unsettled. The unsettledness of the statutory term particular social group is not, as many contemporary realists might suppose, the result of ideological or otherwise strategic decision making on the part of judges; it is the result of a failure of rationality that can be best understood with reference to the fruitful distinctions between different forms of legal rationality that appear in Weber's work and in the contemporary cognitive anthropology literature. The ecologically and formally rational action of judges (Weber [1922] Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1968, 655–56; Gigerenzer, Todd, and the ABC Research Group Reference Gigerenzer and Todd1999) leads to outcomes that are substantively irrational at the system level (Weber [1922] Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1968). In the final section, I highlight the generalizable lessons from the dispute chains for the literatures on judicial decision making and legal settling.

Interpretations of Particular Social Group by the Board of Immigration Appeals

The “well-founded fear” standard for asylum seekers hoping to gain admission to the United States was taken almost word for word from the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 UN Protocol when they were adopted as US law in 1980. So, too, were the categories of protected people, including the category of particular social group, a last-minute addition to the UN Convention during debate at the General Assembly (Hathaway and Foster Reference Hathaway and Foster2014, 423) that could be seen as dramatically expanding the reach of the law. Accordingly, many asylum claims in the United States and internationally turn on the interpretation of that ambiguous and potentially expansive phrase. The judicial interpretation of the phrase remains unsettled in US courts.

The earliest significant statutory interpretation comes in the BIA's 1985 decision Matter of Acosta.Footnote 2 In Acosta, the BIA ruled on the asylum claim of a Salvadoran appellant who was a member of a taxicab drivers’ union (COTAXI), and who claimed a well-founded fear of persecution from antigovernment guerillas whom Acosta believed were behind anonymous threats he had received after refusing to participate in work stoppages that were designed to damage the national economy. Acosta claimed a causal nexus between his fear of persecution and his membership in the social group of COTAXI drivers. The BIA ruled against him, explaining that it interpreted the statutory meaning of particular social group by relying on the doctrine of ejusdem generis:

The doctrine [ejusdem generis, “of the same kind”] holds that general words used in an enumeration with specific words should be construed in a manner consistent with the specific words.… The other grounds of persecution in the [1980 Refugee] Act and the [UN] Protocol listed in association with “membership in a particular social group” are persecution on account of “race,” “religion,” “nationality,” and “political opinion.” Each of these grounds describes persecution aimed at an immutable characteristic: a characteristic that either is beyond the power of an individual to change or is so fundamental to individual identity or conscience that it ought not be required to be changed.… Thus, the other four grounds of persecution enumerated in the Act and the Protocol restrict refugee status to individuals who are either unable by their own actions, or as a matter of conscience should not be required, to avoid persecution. (BIA 1985, 233)

The Acosta decision has been criticized and refined many times in the courts of appeals, but the immutable characteristic test has survived these challenges mostly intact, and it remains the single most important doctrinal standard for the interpretation of particular social group. The case still exerts an important influence on social group interpretation in the courts of appeals. In fact, given that the Supreme Court has never issued a ruling on the interpretation of particular social group for the purposes of refugee status determination, the courts of appeals’ decision-making process is controlled more from below (by the BIA decisions and the requirement of Chevron deferenceFootnote 3 ) than from above. The BIA Acosta decision has influenced courts of appeals decision making on the particular social group question since 1985 without managing to head off disagreements about how to apply the law in practice.

Recognizing that Acosta had proven insufficient on its own to generate settled interpretation of the statute across the courts of appeals, the BIA has twice introduced substantial elaborations on the Acosta standard. In 2006, the agency required asylum seekers claiming membership in a particular social group to show that their group had “social visibility” (BIA 2006, 959–61). At the courts of appeals level, this new language confused the issue more than it clarified. It was subject to criticism, most explicitly in the Seventh Circuit, for “mak[ing] no sense” (Gatimi v. Holder 2009, 615). In 2013, both the Seventh and the Ninth Circuits issued opinions en bancFootnote 4 addressing the meaning of particular social group.Footnote 5 These lengthy en banc opinions, both spurring vigorous dissents within the circuits, demonstrated the continued inadequacy of the social visibility standard to ground a common understanding of particular social group.

In 2014, one year after the Seventh and Ninth Circuit en banc cases, the BIA revised the social visibility requirement in a pair of cases, finding that a particular social group must demonstrate “social distinction” (BIA 2014a, 2014b; Anker Reference Anker2014, 429). The 2014 change seems likely to reverberate through the courts of appeals and to perpetuate interpretive disagreements over the meaning of particular social group for years to come, just as earlier BIA standards have, unless and until the Supreme Court rules on the issue to constrain the existing disagreements.Footnote 6 This new gloss on the core statutory language does not seem likely to alter the basic dynamics that have perpetuated interpretive dispute in the courts of appeals.

The Proliferation of Particular Social Group Interpretive Disputes in the Courts of Appeals

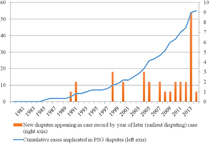

The case studies presented here are drawn from a broader study of decision making and interpretive disputation in the US courts of appeals, for which I systematically gathered data on interpretive disputes among courts of appeals judges over questions of political asylum law (Owens Reference Owens2017). Disputes arise in several dimensions: within panels (i.e., dissents and separately written concurrences), within courts over time (intra-circuit splits), between courts with equal jurisprudential authority (circuit court splits or inter-circuit splits), and courts of appeals holdings overturned by the Supreme Court. From a database of 21,723 political asylum cases appealed to the federal courts of appeals from 1980 (when the Refugee Act introduced the standing definition of refugee into US statutory law) to 2015, I identified 718 distinct interpretive disputes and coded them into several categories. Formally, the majority of interpretive disputes in political asylum law occur within panels. Substantively, the largest plurality occurs over standards of proof (i.e., over whether the undisputed facts of a case meet the relevant legal standard of proof established in statute or case law). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the coded disputes by dimension in the court system. Some disputes involve only two authors or two judging panels split over a question. Other disputes involve multiple judges or panels lending support to one or both sides of single, clearly defined interpretive question. Therefore, the number of dyads in the total network of disputes exceeds the number of legal disputes.

Figure 1. Count of Legal Disputes (Solid Bars) and Disputing Dyads (Dashed Lines) by Dimension of Dispute in the Federal Court System [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

By using keyword searches and the negative case history indexing provided by the Westlaw database, and by comparing my results with the database of asylum decisions compiled by Ramji-Nogales, Schoenholtz, and Schrag (Reference Ramji-Nogales, Schoenholtz and Schrag2007, 2009), I have been able to construct a database that is comprehensive with respect to the legal questions that have prompted disagreement in the federal courts and representative with respect to the distribution of those disputes within and between courts.Footnote 7

For the purposes of this article, only a small number of the cases from this database are at issue. The legal cases that contest the question, “what is a particular social group?” are, collectively, a clear distillation of judicial knowledge work sustained across many different courts and empirical contexts. The organizational rules and norms of the courts may contribute to the engagement and avoidance of legal questions and, correspondingly, to the settling of or failure to settle such questions. But once a particular court in a particular case does engage a question, we can observe how judicial reasoning contributes to its settlement or perpetuation. That is my topic here, and interpretive disputes over the meaning of particular social group are data well suited to this inquiry: the available evidence indicates that they cannot be explained away either as post hoc rationalizations by judges who decided their cases on other grounds or as epiphenomenal to other, “real,” disputes distinct from the apparent disputes over the meaning of particular social group.

I identified thirty-three distinct interpretive disputes over the meaning of particular social group, out of 718 distinct interpretive disputes in the asylum case law record. These disputes roughly subdivide into two types: disputes over whether some other language is a legally permissible clarification of the statutory phrase and disputes over whether some empirically defined group fits the definition. Cases attempting to clarify the rule propose the following specifications: particular social groups as “visible and externally recognizable”; as “voluntary associational relationships”; as characterized by a “common, immutable characteristic”; and as “sufficiently particularized.” The explicitly contested empirical groups are (in the chronological order that the disputes arise before the courts): deserters and persons avoiding military service; families; new entrepreneurs in post-communist Russia; police officers; ethnic Sinhalese; nonnuclear families; elite, landowning cattle ranchers targeted by Maoist groups; ethnic Kongolese; women (gender); members of a military organization; young (or appearing young) attractive Albanian women forced into prostitution; middle-class small business owners; witnesses who testify against gang members; and schizophrenic and bipolar individuals in Tanzania who exhibit outwardly erratic behavior.

Opinion length and the number of prior authorities cited are simple but reasonable measures of the depth of judicial engagement in a case, and both provide evidence that the deciding judges saw the questions raised in the fifty-five disputing cases as especially important and worthy of extended treatment. The mean length of immigration law cases in the US Federal Reports from 1980 to 2002 is 5.0 pages with a standard deviation of 3.3 pages.Footnote 8 By contrast, the fifty-five asylum cases engaged in explicit disputes over the meaning of particular social group have a mean page length of 10.0 with a standard deviation of 6.9. Those fifty-five cases cite on average twenty-six authorities, while the average for immigration cases from 1980 to 2002 is thirteen.

Other contextual factors fail to explain away interpretive disputes over the meaning of particular social group. The distribution of cases that are implicated in these disputes suggests that the appearance of the disputes cannot be put down to roles of litigators or amici curiae or to the geographic origin of the claim. The cases implicated in particular social group disputes involve male (twenty-five), female (twenty), and transgender (one) appellants as well as families (nine). They come from Central America (twenty-four), South America (eight), Eastern Europe and the former USSR (six), China (three), Iran (two), South Africa (two), and nine other countries scattered across Asia and Africa.

The preponderance of cases from Central and South America reflects both the large number of asylum seekers from those countries and the difficulty that the courts have had in assessing the claims of those fleeing gang violence and violence by guerilla groups in failed states. But the spread of cases that raise disputes over the meaning of particular social group beyond Central and South America indicates that the conceptual difficulty raised by the particular social group question can arise in quite different contexts, even when the case or cases in question do not present an obviously new or especially difficult question of law. A dispute arose between the Seventh and Third Circuits in 2013, for example, over whether Christians who converted to Christianity after an order of removal from the United States are part of the same social group as longstanding Christians (Shu Han Lin v. Holder 2013; Li Zhang v. Atty. Gen. of the United States 2013). This dispute arises notwithstanding many cases prior to 2013 dealing with the asylum claims of Chinese Christians.

The resources and networks of particular litigators cannot account for when particular social group disputes appear in the case law record. Seven cases out of fifty-five involve counsel for petitioners who are repeat players within this set of cases, and none of those counsels were representatives of elite or especially large law firms. In only three cases did one of the 350 largest law firms in the country represent the petitioner.Footnote 9 In all other cases, the organization representing the petitioner was a small law office—often a specialized immigration clinic—or else no legal counsel is listed in the opinion.

Amicus curiae briefs were filed in eight of the fifty-five cases: two were filed by the UNHCR; two by the ACLU; one by the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinic, and one by Deborah Anker, the current and longtime director of the Harvard Clinic; one each by the National Immigrant Justice Center, Human Rights Watch Americas, and a handful of other organizations. These institutions are repeat players in political asylum disputes that more plausibly have the knowledge base and institutional power to influence the framing of problems and case outcomes, but there is no evidence that the interventions of the amici are crucial to the development of interpretive disputes in the case law. The outcome is favorable to the petitioner in exactly half the cases in which an amicus brief is submitted (four out of eight); the same success rate applies for petitioners in all cases implicated in disputes over the meaning of particular social group (twenty-seven out of fifty-five). In none of the eight cases do the judges indicate that the amicus briefs influenced their holding on the narrow question of how to interpret particular social group. The amici do have some success in identifying cases that will turn out to be jurisprudentially important. Across all asylum law cases, those in which amici intervene include many that are among the most highly cited in the case record,Footnote 10 but there is no clear evidence that amici have a significant ability to shape the framing of particular social group interpretation or affect the outcomes of the cases disputing the meaning or application of particular social group. This is moderately surprising in relation to the literature on the role of amicus briefs in federal court decision making, which has usually found some influence of amicus briefs on case outcomes (although most of this literature has focused on amicus briefs in the Supreme Court rather than in the courts of appeals; see Collins Reference Collins2004, 808; Epstein, Landes and Posner Reference Epstein, Landes and Posner2013, 321–23).

In sum, particular social group disputes have repeatedly arisen in court cases absent any involvement of powerful litigators or amici curiae. They have arisen in cases that span the globe, although failed states and gang violence in Central and South America have generated cases that involve this conceptual puzzle with special frequency.

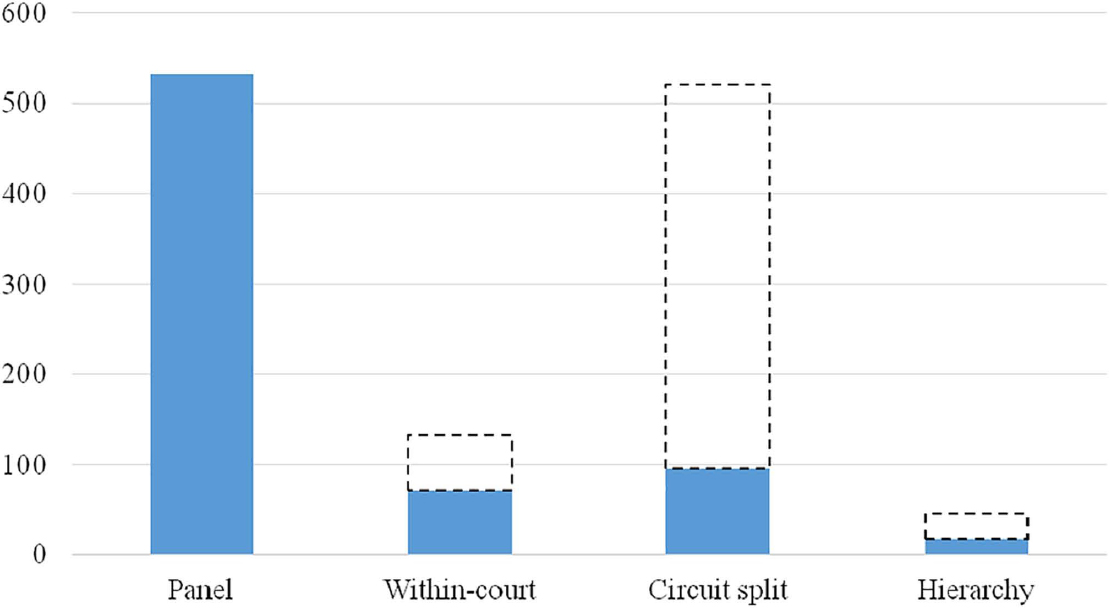

Neither the formal rationality of legal reasoning nor the institutional norm of deference to precedent have been sufficient to settle the legal meaning of particular social group in the courts of appeals. New cases have been implicated in these overlapping dispute chains at an ever-accelerating rate (the convex trend line in Figure 2). The especially high volume of new interpretive disputes appearing in 2013 is driven in part by two long and complex en banc opinions published in the Seventh and Ninth Circuits mentioned above (Cece v. Holder 2013; Henriquez-Rivas v. Holder 2013). Both opinions were substantial efforts to settle the meaning of particular social group within their respective circuits; both prompted dissents. The Ninth Circuit's Henriquez-Rivas decision overturned prior Ninth Circuit law on the relevance of social visibility to particular social group identification. The Seventh Circuit's Cece disagreed with a prior Sixth Circuit opinion. Thus, between them these two opinions generated several new interpretive disputes in the case law record. Whether they will succeed in settling the question within the Seventh and Ninth Circuits for the future remains to be seen.

Figure 2. Proliferation of Particular Social Group Disputes Over Time [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Judicial Reasoning and the Persistence of Unsettled Law

I now turn to a close analysis of two sets of cases where settling proved elusive for several years. The first set of cases concerns whether a family qualifies as a particular social group for the purposes of refugee-status determination. The second set consists of three cases implicated in a second-order dispute over whether two tests for the identification of a particular social group are compatible. I focus on these two dispute chains because they look different in terms of network structure, but they reveal similar mechanisms at work that prevented the law from settling.

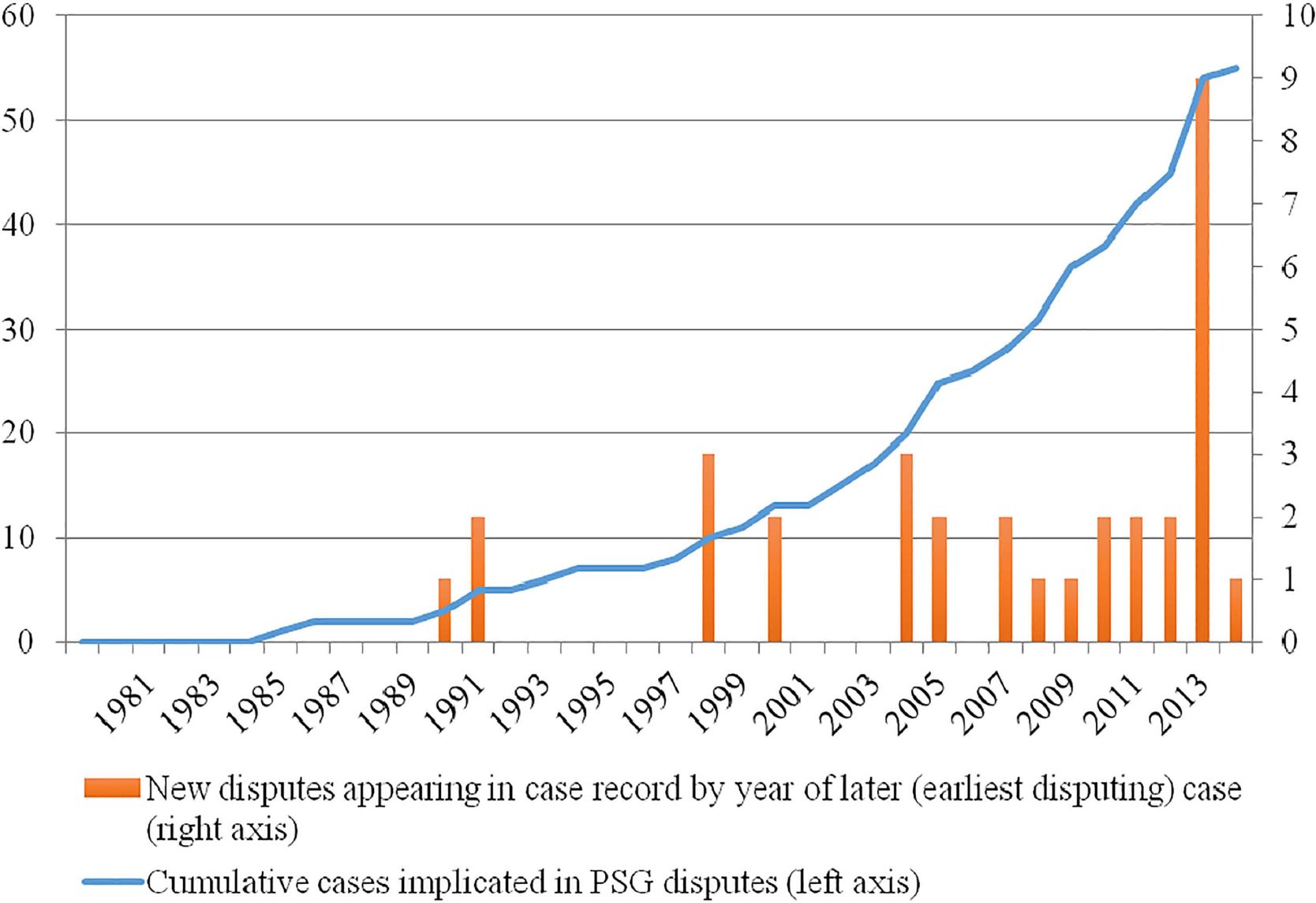

The dispute over whether a family can constitute a particular social group implicates nine judicial opinions, eight of them from the Ninth Circuit, which hears a large plurality of all asylum claims.Footnote 11 Figure 3 gives a visual representation of the dispute chain. The family question provides a good illustration of how the uncontroversial application of legal knowledge and heuristics in a local context—what cognitive anthropologists have called ecological rationality—can contribute to the production of legal disputes and hence unsettled legal concepts.

Figure 3. Network Structure of Case Study 1

The Ninth Circuit made its first comment on the possibility of family as a social group in 1986 in Sanchez-Trujillo v. INS. The entire treatment of the question in that case runs as follows: “perhaps a prototypical example of a ‘particular social group’ would consist of the immediate members of a certain family, the family being a focus of fundamental affiliational concerns and common interests for most people” (1986, 1576). Five years later, the Ninth Circuit ruled on the family question again, this time in the opposite direction: “[the petitioner] cites to no case that extends the concept of persecution of a social group to the persecution of a family, and we hold it does not. If Congress had intended to grant refugee status on account of ‘family membership,’ it would have said so” (Estrada-Posadas v. US INS 1991, 919). The Estrada-Posadas decision does not cite Sanchez-Trujillo. There then follow two decisions by the Ninth Circuit that take Sanchez-Trujillo as the ruling authority without citing Estrada-Posadas (Mgoian v. INS 1999; Pedro-Mateo v. INS 2000). Meanwhile, the Seventh Circuit, in Iliev v. INS (1997), issued its own ruling on the family question, citing Sanchez-Trujillo positively, as well as a number of authorities in the Seventh Circuit that implicitly treated family as a particular social group.

The later cases addressing the family question take notice of the split authorities. Hernandez-Montiel v. INS (2000) is the only decision in the case record to follow the Estrada-Posadas precedent. It does so with some ambivalence and in the context of casting doubt on Sanchez-Trujillo's voluntary association standard: “in Sanchez-Trujillo, we [the Ninth Circuit] recognized a group of family members as a ‘prototypical example’ of a ‘particular social group.’ Yet, biological family relationships are far from ‘voluntary.’ We cannot, therefore, interpret Sanchez-Trujillo's ‘central concern’ of a voluntary associational relationship strictly as applying to every qualifying ‘particular social group.’” The court's holding in favor of Estrada-Posadas comes only in a footnote: “we have since held that a family cannot constitute a particular social group under 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42)(A)” (2000, 1092). In Chen v. Ashcroft (2002), the Ninth Circuit reverts to agreement with Sanchez-Trujillo on the family question, but again with hedging language. Chen refers to the decision in Estrada-Posadas as “dicta”Footnote 12 and notes, without explicitly asserting that this is a relevant legal distinction, that the family discussed in that case was not a nuclear family. Chen then affirms the Sanchez-Trujillo decision as “the law of our Circuit” (1115).

The final two entries to date in this unfolding dispute are Molina-Estrada v. INS (2002) and Thomas v. Gonzales (2005). Molina-Estrada acknowledges Ninth Circuit law that “in some circumstances” a family can constitute a particular social group while still citing the contrary holding in Estrada-Posadas. Of all the opinions here discussed, Thomas, which was decided en banc, provides the most extensive discussion of the previous case law. Thomas also most clearly exhibits the judicial discomfort and sense of threat to professional legitimacy that can arise from interpretive disputes in case law. The Thomas decision first reviews how other circuits have implicitly and explicitly treated the question of whether a family counts as a particular social group and finds “no out of circuit authority to the contrary.” It then observes, “inexplicably, our circuit has generated two diverging lines of authority on whether family or kinship ties may give rise to a particular social group. At least two panel decisions have squarely held that a ‘family’ cannot constitute a ‘particular social group.’… We have also held the opposite” (2005, 1186–87). The en banc Thomas panel finally holds with the majority of earlier cases and gives some further specificity to the holding in response to the government brief in the case:

Reconciling these contrary lines of intracircuit authority is not possible. Therefore, consistent with the views of the BIA and our sister circuits, we hold that a family may constitute a social group for the purposes of the refugee statutes. We overrule all of our previous decisions that expressly or implicitly have held that a family may not constitute a particular social group within the meaning of 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42)(A).… We decline to hold, as the government urges, that a family can constitute a particular social group only when the alleged persecution on that ground is intertwined with one of the other four grounds enumerated in 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42)(A), 1231(b)(3)(A). (1187–88)

There is a striking change in the rhetorical treatment of this question over twenty years, despite the fact that almost all the cases dealing with it come from the same circuit court. Sanchez-Trujillo's commentary on family as a particular social group exists only as a manifestation of the judicial tendency and sense of professional obligation to establish precedential standards through incremental generalization. The petitioner in Sanchez-Trujillo argued that he was a member of the social group “young, urban, working-class males of military age who had maintained political neutrality” in El Salvador, so the question of family as a particular social group was unnecessary to decide the case. Written in the early years of Refugee Act statutory interpretation, Sanchez-Trujillo is forward looking—aspiring to settle future anticipated disputes—instead of backward looking, as is the embarrassed reconciliation of intra-circuit dispute in Thomas. The cases under discussion neatly divide into an earlier set (from Sanchez-Trujillo to Pedro-Mateo) that take no notice of the split authorities, and a later set (Hernandez-Montiel to Thomas) that do take notice.

The standard techniques of legal interpretation are everywhere evident in these cases, and there is no evidence that the authoring judges disagree about the appropriateness of those techniques. The generalizing but strictly unnecessary comment regarding the family as particular social group in Sanchez-Trujillo is fully in the spirit of “judge-centered incrementalism” described by Schauer (Reference Schauer2009, 106), and even when later cases disagree with the holding, they do not dispute the appropriateness of the argumentative approach. The Seventh Circuit in Iliev follows the standard practice of privileging its own institutional precedent over the precedent of other circuits and so avoids a deep engagement with the interpretive dispute, even while acknowledging that it exists in the Ninth Circuit. The later Ninth Circuit cases model a variety of strategies of legalist interpretation. Estrada-Posadas looks to plain meaning in the statutory text and legislative intent to answer the question, and it does so apparently with little difficulty. Chen and Molina-Estrada take notice of the circuit split, and so they have a harder task in reaching a decision than either Iliev or Estrada-Posadas. Nevertheless, both Chen and Molina-Estrada are able to avoid the messy conclusion in Thomas (“reconciling these contrary lines of intracircuit authority is not possible”) by employing completely standard legalist tools of interpretation. The tactic adopted by the court in Chen is to downgrade the statement in Estrada-Posadas to dicta and hence not to treat it as binding precedent. The tactic adopted in Molina-Estrada is to imply a finer distinction of factual circumstances than the preceding cases. The court in Molina-Estrada references the prior holding that a family is a particular social group “in some circumstances,” but declines to elaborate on the circumstances in which it is and in which it is not. The court then decides the case on other grounds anyway: “assuming that Petitioner's family is a ‘particular social group’ within the meaning of the statute, he has not established that he was persecuted ‘on account of’ his family membership” (1095).

The first reaction of a lawyer or judge to this extended discussion of the dispute over family as a particular social group may be that it is much ado about nothing. There are only two outlier cases, and the question has now been apparently firmly settled in the only circuit in which it generated any confusion. However, treating this chain as a single dispute distributed across fourteen dyads and nine cases possibly understates the degree of disagreement expressed here. Wrapped up in the dispute is inconsistency over whether the answer to the family question in Estrada-Posadas is dicta or Ninth Circuit precedent. Several of these cases also question the soundness of the Sanchez-Trujillo voluntary association test and its compatibility with the notion of family as prototype of a particular social group, which creates an overlapping but analytically distinct chain of disputation. Disputes like this one are not the result of failures of the legalist decision-making model in particular cases (see Table 1). They are direct consequences of its application.

Table 1. Legalist Standards and Divergent Outcomes in the Dispute Over Family as a Particular Social Group

| Case | Interpretive Tools and Strategies | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Sanchez-Trujillo → | Inductive incremental theorizing → | Family a particular social group |

| Estrada-Posadas → | Textual plain meaning and legislative intent (Congress) → | Family not a particular social group |

| Iliev → | Circuit authority outweighs extra-circuit authority → | Family a particular social group |

| Mgoian → | Deference to precedent (stare decisis) → | Family a particular social group |

| Pedro-Mateo → | Stare decisis → | Family a particular social group |

| Hernandez-Montiel → | Stare decisis → | Family not a particular social group |

| Chen → | Stare decisis; dicta not binding → | Family a particular social group |

| Molina-Estrada → | Stare decisis; divergent authorities distinguishable on the facts → | Family a particular social group |

| Thomas → | Conflicting lines of precedent not reconcilable; consistency with BIA and circuit courts → | Family a particular social group |

The dispute chain over the question of whether a family is a particular social group illustrates that, at least in this narrow instance, neither the norm of deference to precedent, nor the canons of construction, nor any other techniques of legal interpretation contribute in the expected way to the system-wide settling of a single, narrowly defined legal question. These techniques, consistently applied, instead accomplish just the opposite: the perpetuation of dispute. In the later cases of Chen and Molina-Estrada, the authoring judges sought to bolster the formal rationality of the particular decision at hand by reading Estrada-Posadas's opinion as dicta (Chen) and by introducing a new but unarticulated distinction between the earlier decisions on factual grounds (Molina-Estrada). Because these two opinions do not acknowledge the broader inconsistency that already existed in the Ninth Circuit's case law, they do nothing to move it toward resolution. It was only when the en banc court in Thomas grasped the nettle of the circuit's previous inconsistency that the court reached a settling of intra-circuit law that looks likely to persist without future disruption. The pattern is much the same when we look across a wider set of cases that have grappled with the meaning of particular social group. As in the debate over family, the application of standard techniques of statutory interpretation along with incremental generalization has produced many cases that are, like the family cases, mutually irreconcilable (Table 2).

Table 2. Key Moments of Particular Social Group Interpretation Contributing to the Perpetuation of Dispute

| Date | Claim | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Immutable characteristic test | BIA, Acosta |

| 1986 | Voluntary association test Family is a particular social group |

9th Cir., Sanchez-Trujillo

9th Cir., Sanchez-Trujillo |

| 1987 | ||

| 1988 | Police officers as such are not a particular social group | BIA, Fuentes |

| 1989 | ||

| 1990 | ||

| 1991 | Family not a particular social group Particular social groups must be visible and externally recognizable |

9th Cir., Estrada-Posadas

2d Cir., Gomez |

| 1992 | ||

| 1993 | Gender by itself not a particular social group | 3d Cir., Fatin |

| 1994 | ||

| 1995 | ||

| 1996 | ||

| 1997 | ||

| 1998 | Voluntary association test at odds with BIA Acosta | 7th Cir., Lwin |

| 1999 | ||

| 2000 | Immutable characteristic test not dispositive | 9th Cir., Hernandez-Montiel |

| 2001 | ||

| 2002 | ||

| 2003 | 2d Cir. Gomez ruling at odds with BIA Acosta | 6th Cir., Castellano-Chacon |

| 2004 | ||

| 2005 | ||

| 2006 | Social visibility test | BIA, C-A- |

| 2007 | 2d Cir. Gomez ruling compatible with BIA Acosta | 2d Cir., Koudriachova |

| 2008 | ||

| 2009 | Social visibility test rejected | 7th Cir., Gatimi, Ramos |

| 2010 | Gender by itself a particular social group | 9th Cir., Perdomo |

| 2011 | ||

| 2012 | Particular social groups must be share a trait that is (1) sufficiently particularized, (2) common and immutable, (3) socially visible | 6th Cir., Gomez-Guzman |

| 2013 | Service as a policeman can ground a particular social group claim Service as a policeman cannot ground a particular social group claim |

11th Cir., Gavilano-Amado (dissent) 11th Cir., Gavilano-Amado |

| 2014 | Social distinction test | BIA, M-E-V-G, W-G-R- |

Several other case law disputes have a form similar to the dispute over family, with multiple cases lined up on either side of a question that implicates a large class of refugee claims. Other examples include the dispute over the validity of the social visibility and voluntary association standards. Several other particular social group disputes manifest as very specific questions that are contested within a single panel or between two cases only. I next turn to one of these dispute chains, that is, one that has a substantially different network structure from the dispute over family as a particular social group.

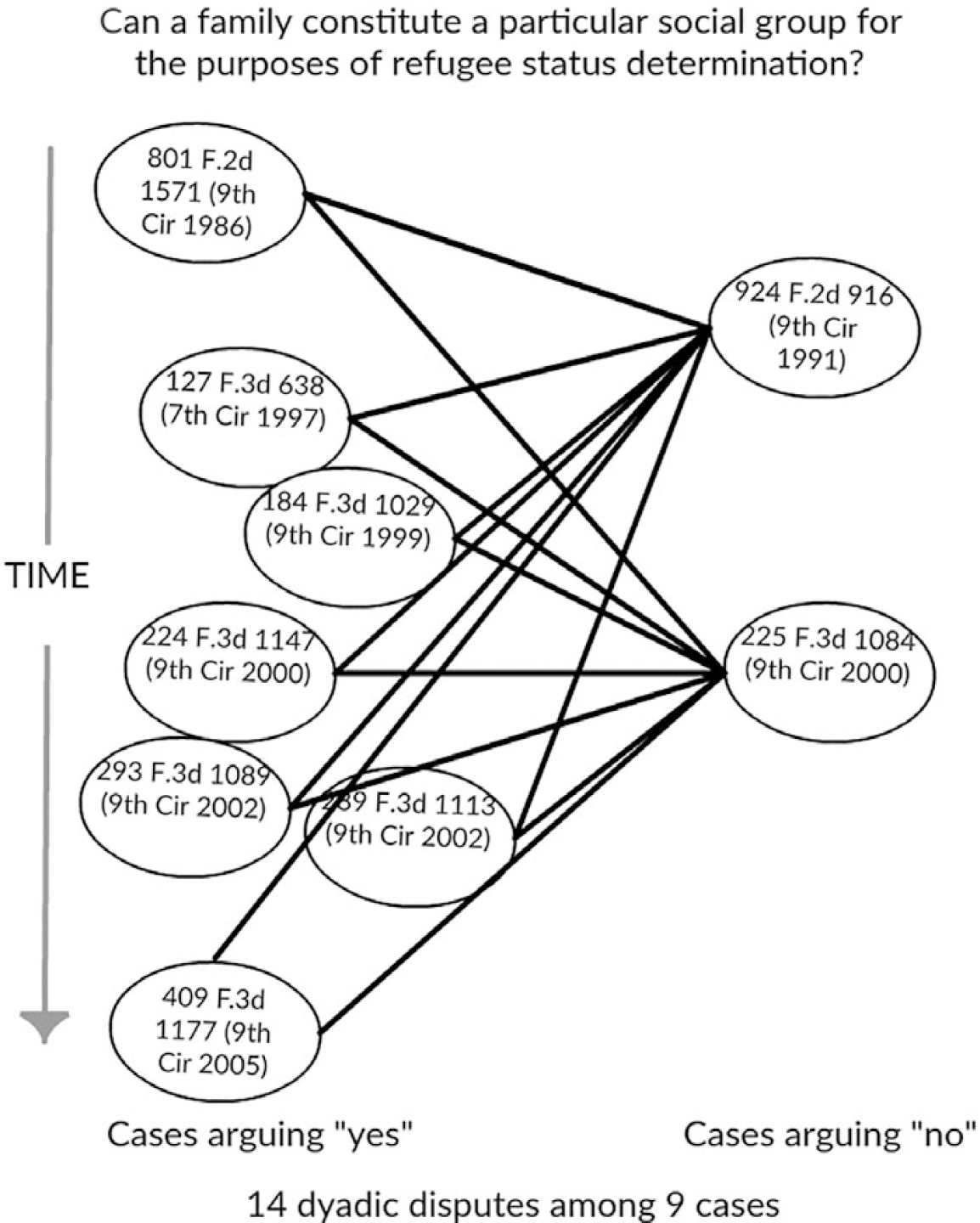

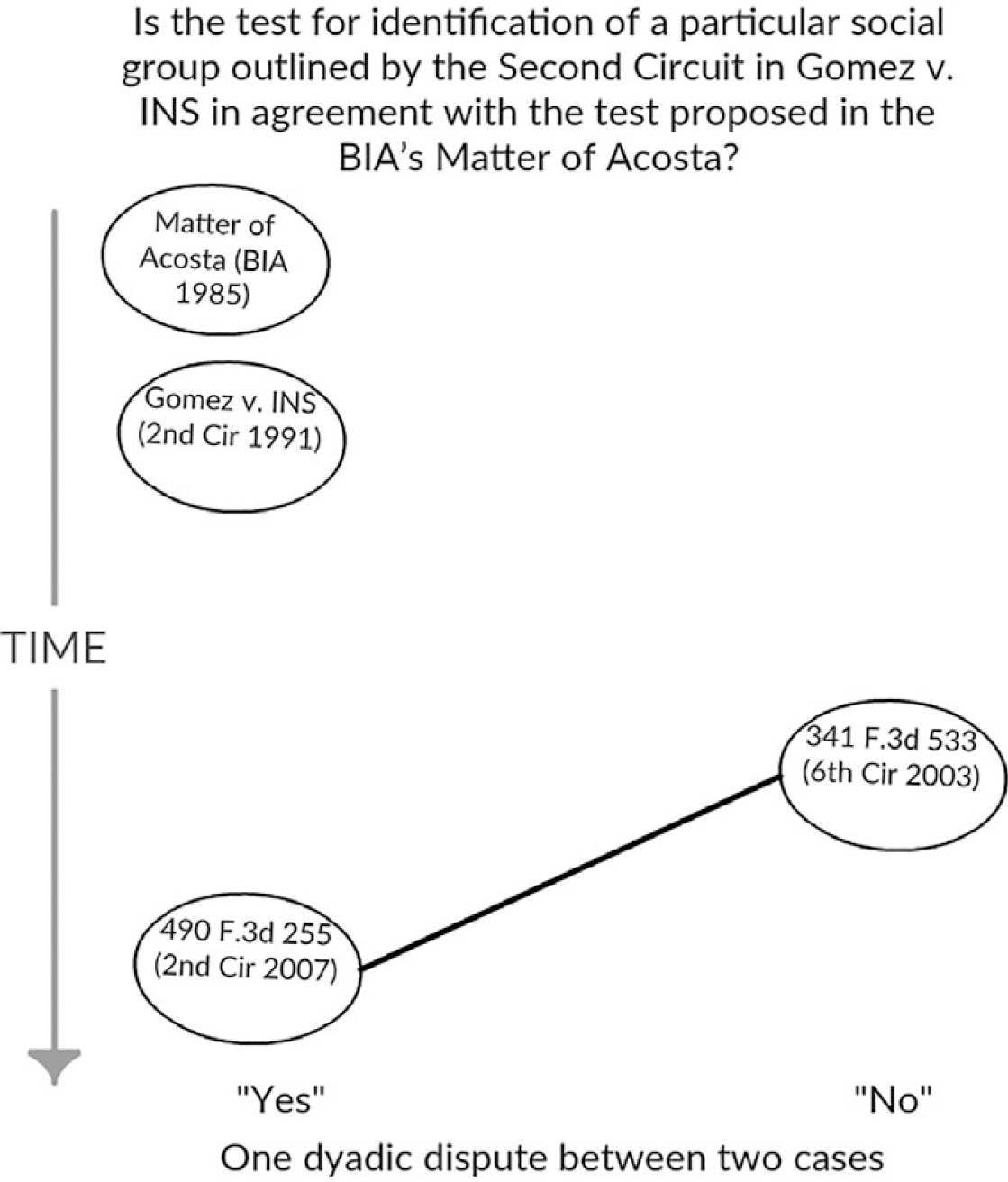

My second case study arises between the Sixth Circuit and the Second Circuit over the question: “Is the test for identification of a particular social group outlined by the Second Circuit in Gomez v. INS (1991, 947 F.2d 660) in agreement with or at odds with the test proposed in the BIA's Acosta?” The Sixth Circuit in Castellano-Chacon v. INS (2003) holds that the answer is no; the Second Circuit in Koudriachova v. Gonzales (2007) argues that the answer is yes. The BIA in Acosta, as we have seen, introduced the immutable characteristic test. The Second Circuit in Gomez writes:

“Particular social group” has been defined to encompass “a collection of people closely affiliated with each other, who are actuated by some common impulse or interest.”… A particular social group is comprised of individuals who possess some fundamental characteristic in common which serves to distinguish them in the eyes of a persecutor—or in the eyes of the outside world in general … (“A ‘particular social group’ normally comprises persons of similar background, habits or social status”). (664, emphasis in original)

The Second and the Sixth Circuits, then, disagree: Are these two tests compatible or not? Figure 4 gives a visual representation.

Figure 4. Network Structure of Case Study 2

In Castellano-Chacon, the Sixth Circuit interprets the Second Circuit holding in Gomez as follows: “the Second Circuit adopted the Ninth Circuit's ‘voluntary associational relationship’ standard [from Sanchez-Trujillo], but additionally noted that the members of a social group must be externally distinguishable” (546). Gomez does cite Sanchez-Trujillo, although not the particular phrase “voluntary association,” in making reference to “a collection of people … actuated by some common impulse or interest” (664). The phrase “externally distinguishable” in Castellano-Chacon is a close paraphrase of “possess some fundamental characteristic … which serves to distinguish” from Gomez (664). Castellano-Chacon thus does seem to describe fairly a two-step process of identification in Gomez. The only clear separation between the two accounts on a first reading is the reference in Gomez to the required external characteristic as “fundamental,” which is not repeated in Castellano-Chacon.

However, the Second Circuit in Koudriachova rejects the Sixth Circuit's separation of the BIA test and the Gomez test:

[The] broad dicta in Gomez … should not be read as setting an a priori rule for which social groups are cognizable. … Rather, Gomez should be read as standing for the proposition that an individual will not qualify for asylum if he or she fails to show a risk of future persecution on the basis of the membership claimed. (261)

In other words, Koudriachova holds that the Sixth Circuit in Castellano-Chacon read Gomez to be proposing a determining rule, when in fact Gomez is no more than dicta affirming that group membership matters. As in the first dispute chain discussed above, this disagreement arises from a combination of (1) inductive theorizing from cases that fails to command complete support in subsequent cases and (2) the application of commonly accepted interpretive tools and strategies in different contextual circumstances, with contextual circumstances changing by dint of empirical variation in the cases and the wholly contingent order in which the Second and Sixth Circuits heard these particular cases (Table 3).

Table 3. Legalist Standards and Divergent Outcomes in the Dispute Over Acosta and Gomez Standards

| Case | Interpretive Tools and Strategies | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Acosta → | Ejusdem generis → | Immutable characteristic test |

| Sanchez-Trujillo → | Evaluation of the statutory language; legislative intent (UN and Congress) → | Voluntary association test |

| Gomez → | Chevron deference; consistency with BIA and sister circuits desirable → | There is a single particular social group standard |

| Castellano-Chacon → | Chevron deference → | Acosta and Gomez are not compatible |

| Koudriachova → | Chevron deference; read earlier circuit opinions as favorably as possible → | Acosta and Gomez are compatible |

The Second Circuit's Gomez cites the BIA's Acosta, the Ninth Circuit's Sanchez-Trujillo, and the First Circuit's Ananeh-Firempong v. INS (1985) as relevant precedents, but it also adds some further elaboration on how the particular social group standard ought to apply to the empirical case at hand:

Gomez failed to produce evidence that women who have previously been abused by the guerillas possess common characteristics—other than gender and youth—such that would-be persecutors could identify them as members of the purported group.… Certainly, we do not discount the physical and emotional pain that has been wantonly inflicted on these Salvadoran women.… We cannot, however, find that Gomez has demonstrated that she is more likely to be persecuted than any other young woman. (664)

When the Sixth Circuit decided Castellano-Chacon in 2003, Gomez's conciliatory reading of the prior case law was no longer available. In the intervening years, case law from several other circuits exploded the notion in Gomez that a single, coherent standard governed the interpretation of particular social group in the federal courts and the BIA. The Ninth Circuit abrogated its earlier holding in Sanchez-Trujillo, and the BIA and a few other circuits explicitly rejected voluntary association as a test for or determining feature of a particular social group. The Sixth Circuit follows two simple heuristics in imposing its own order on the conflict of interpretations between the circuits: (1) acknowledge circuit splits when they exist and (2) when your own circuit has no existing precedent on the issue, adopt Chevron deference as the first resort. The judges write, “we have not previously stated a specific test in the Sixth Circuit, and in doing so now we recognize the deference due the BIA's interpretation of the INA insofar as it reflects a judgment that is peculiarly within the BIA's expertise” (546).

To make sense of the explicit dispute between the BIA and the Ninth Circuit's Sanchez-Trujillo, the Sixth Circuit had to decide how to classify the Gomez decision. It did so in apparently the least cognitively demanding way, namely, by reading Gomez as a third test, one that splits the difference between Acosta and Sanchez-Trujillo: “the Second Circuit adopted the Ninth Circuit's ‘voluntary associational relationship’ standard, but additionally noted that the members of a social group must be externally distinguishable” (546).

Finally, the Second Circuit in Koudriachova could not easily ignore the circuit precedent established in Gomez or ignore the suggestion by the Sixth Circuit that Gomez violates the requirement of Chevron deference. To avoid the embarrassing conclusion that the Gomez decision violated the obligation of Chevron deference or committed an error of law by failing even to consider the requirement of Chevron deference, the Second Circuit in Koudriachova minimizes the meaning of its own earlier decision, both legally (calling it dicta rather than precedent) and substantively (denying the notion that Gomez involved “setting an a priori rule” [262]). The Sixth and Second Circuit panels in Castellano-Chacon and Koudriachova respond to different contextual imperatives to rely on different, equally valid, sources of law and different, but universally acceptable, interpretive tools to reason to their decisions. This alone is sufficient to explain the dispute that arises between the two cases.

Conclusion

My dispute chain analyses show how interpretive disputes in the courts of appeals can persist rather than settle as a consequence of the application of standard legalist techniques of judicial reasoning. The judicial focus on reconciling and extending precedents can create more unsettled law when judges operate with different frames of reference from case to case. We see this dynamic in action in both dispute chains analyzed above. Furthermore, the tools of legal interpretation that we see judges relying on in the cases that make up these dispute chains—reliance on precedent and several well-known canons of construction—are the standard tools of legal interpretation applied across all domains of law. We should therefore not be surprised to find similar patterns of dispute chain production to what we find in reference to the particular social group statutory standard across other areas of law.

These dispute chains reveal a tension in the internal rationality of the law that Weber's formal/substantive rationality distinction helps us to understand. Weber defined “formally rational law” as characterized by clear rules and clear explanations of how legal authorities reached their decisions (Weber [1922] Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1968, 656). Formally irrational legal judgments are, by contrast, those that are handed down with no justification or reasoning, deductive or inductive. Weber's definition of substantive rationality in law focused on different qualities of legal judgments: in his framework, a substantively rational legal system is one in which the facts of a case are evaluated only against general norms and not against ethical, emotional, or political bases. Weber recognized that substantive rationality does not logically require formal rationality,Footnote 13 but his overarching thesis was that the two developed together in industrial capitalist societies.

Close analysis of dispute chains dealing with unsettled statutory concepts in the US federal courts shows that, ironically, it is instances where judges engage in detailed inductive, incremental but non-empirical theorizing in an effort to meet a high standard of formal rationality that put the substantive rationality of asylum case law at greatest risk. In the case of particular social group interpretation presented here, judicial inductive theorizing leads directly to disputes about whether particular social groups are characterized by immutable characteristics, voluntary associations, social visibility, social distinction, or something else. Judicial disputes on these issues make it more difficult for the judiciary as a whole to maintain a consistent stance on what needs to be done to fulfill the (substantively rational) purpose of the 1980 Refugee Act, “to provide a permanent and systematic procedure for the admission to this country of refugees of special humanitarian concern to the United States.” These disputes, once they arise, have proven difficult to settle without resort to the principle of stare decisis and the authority of institutions over and against the authority of reason (a formally irrational decision mechanism, in Weber's terms). Conversely, oracular judgments in asylum cases—judgments that offer no exposition of the meaning of particular social group—are the judgments that most effectively guard against the most conspicuous failures of asylum law's substantive rationality.

Contemporary social scientific studies of judicial decision making have mostly bypassed the internal tensions in legal rationality discussed in this article because they have mostly given up paying any attention to the internal, formal logic of judicial decision making. They have done so on the premise that the interesting variation in outcomes is best understood as a consequence of the formal features of cases (the identities of the interested parties, the age of controlling precedents, etc.) and the distribution of judges’ instrumental interests. Posner (Reference Posner2008, 1) makes the point clearly: legalism has not disappeared, “but its kingdom has shrunk and grayed to the point where today it is largely limited to routine cases.” In this article, I have sought to recover a way to assess social scientifically the role of legal reasoning and the path dependencies of case law development in generating legal disputes, thereby bringing the study of judicial decision making into the fold of law and society literature on the settling of legal norms and concepts.

The judicial interpretation of particular social group in the asylum statute is rational, but it is rational only in a highly circumscribed way. Its rationality does not confer the benefits that we usually suppose rational thought to provide: inferences and outcomes that can be predicted in advance, internal consistency by different decision makers, and substantive defensibility in terms of ultimate ends and/or values. Networks of case law disputes, such as those modeled in Figures 3 and 4, would be sparser—with fewer nodes and less dense ties—if each case in the case record decided the particular social group question on the narrowest possible grounds with the least possible exposition, prioritizing the preservation of substantive rationality at the expense of formal rationality.

The explanation I have advanced for how judicial interpretive disputes are generated is focused on what can be inferred from the textual written text of judicial decisions and the patterns of dispute chains developing over time within and between courts. My argument here leaves aside questions about the phenomenological level of decision making that are fundamentally inaccessible from the available textual evidence. Why, for example, did the authors of Estrada-Posadas fail to cite or perhaps even fail to notice the prior Ninth Circuit precedent in Sanchez-Trujillo? The question is meaningful, and it is a neat demonstration of the contingency of history in determining legal case outcomes. The protracted Ninth Circuit dispute over whether a family is a particular social group might not have occurred if the authors of Estrada-Posadas had taken note of the decision in Sanchez-Trujillo, or if the authors of Sanchez-Trujillo had taken note of the BIA's Acosta. However, a conclusive explanation of the observed outcome over and against the counterfactual one is not recoverable. If it were, it would have to be given as an account of the lived experience of the decision makers: How does a judge experience the process of deciding a case? How did the process unfold in real time—was the case poorly researched, was there a miscommunication between the judge and his clerks, did the judge consciously or unconsciously allow political preference for how the case should come out to guide his thinking?

One possibility is that research into the lived experience of judges would find that they regularly opt for tools of legal interpretation that are cognitively least demanding and avoid direct disputation when possible. Empirical work in cognitive psychology and cognitive anthropology provides evidence that this is how decision makers in general tend to act (e.g., Gigerenzer, Todd, and the ABC Research Group Reference Gigerenzer and Todd1999; Gigerenzer and Engel Reference Gigerenzer and Engel2006; Ryo Reference Ryo2016), and as a working hypothesis, this may help us understand how judges break ties between conflicting decision-making heuristics with equal institutional legitimacy (cf. Llewellyn Reference Llewellyn1960; Schauer Reference Schauer1988; Macey and Miller Reference Macey and Miller1992). The study of conceptual settling in judicial decisions can therefore be a site for fruitful interdisciplinary collaboration as well as an area of further inquiry for law and society scholarship.