Introduction

In the United States, privatization has been described as “virtually a national obsession” (Metzger Reference Metzger2003, 1369). Although the scope of private‐sector involvement in delivering quasigovernmental services is more pronounced in the United States than elsewhere, throughout the countries that are generally characterized as neoliberal or liberal market economies (see, e.g., Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Cavadino and Dignan Reference Cavadino and Dignan2006), public services have been radically reconstituted based on a belief in the superiority of market solutions and private‐sector management techniques. In the United Kingdom, almost 50 percent of the annual public‐sector spending is now contracted out to private companies (National Audit Office 2013), including back‐office functions, such as IT support and facilities management, process and case management, such as pensions administration, and frontline activity, ranging from waste collection to nuclear weapons maintenance to the management of health and correctional services. In recent years, the increasing incursion of private providers into these frontline areas has generated considerable unease among legal and social scholars, for, as Reference MetzgerMetzger 2003 argues, such developments “reveal a trend of greater discretion and broader responsibilities being delegated to private hands” (2003, 1369) in areas where service users are typically powerless and highly dependent. Discussing the transformation of the US welfare state, Smith and Lipsky note that the delegation of state power gives responsibility to nonstate actors to make a multitude of “fateful decisions” (Reference Smith and Lipsky1998, 12) about people in vulnerable circumstances.

Much of the discussion of the impact of contracting out such services has characterized practitioners as “street‐level bureaucrats”: “public service workers who interact with citizens in the course of their jobs, and who have substantial discretion in the execution of their work” (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980, 3). In translating policy into “daily, situated practice on the ground level” (Hjörne, Juhila, and van Carolus Reference Hjörne, Juhila and van Nijnatten2010, 303) and in acting as gatekeepers to institutional resources, street‐level bureaucrats wield considerable power to determine both the concrete form and the individual experience of government policy. Such depictions highlight the role of street‐level bureaucrats as frontline representatives of government policy and emphasize the complexity and consequences of this kind of work. As Smith and Lipsky note, given such conditions, questions remain as to the suitability of market logic:

when it comes to purchasing the care and control of drug addicts, the safety and nurturing of children, the relief of hunger and the regulation of family life (through child protection activities) from private agencies, other values than efficiency are at stake. (Smith and Lipsky Reference Smith and Lipsky1998, 11)

From this perspective, prison privatization represents a particularly striking example of the delegation of state power to private agencies. The deprivation of liberty is generally considered a core state function and while careful contractual arrangements might nominally maintain a split between the allocation and administration of punishment (see Harding Reference Harding1997), the realities of prison life mean that, in practice, private providers exercise “enormous coercive powers over the inmates in their custody” (Metzger Reference Metzger2003, 79; see also Freeman Reference Freeman2001).

Viewed from a more theoretical perspective, however, the privatization of punishment is consistent with—indeed, a core element of—neoliberal state configuration. As both Bernard Harcourt and Loïc Wacquant have argued, although at first sight “the enlargement and exaltation of the penal sector” (Wacquant Reference Wacquant2009, 305) appears incompatible with the neoliberal belief in minimal government, an expansive penal system may be necessary to enforce and uphold an increasingly deregulated economy—to prevent “market bypassing” and “inefficiencies” (in the terms of its advocates; see Harcourt Reference Harcourt2011, 52) and to impound or discipline those who threaten the logic and stability of the free market: “‘Small government’ in the economic register thus begets ‘big government’ on the twofold frontage of workfare and criminal justice” (Wacquant Reference Wacquant2009, 308).

The links between neoliberal discourse, with its privatizing tendencies, and the upsizing of the penal state have, if anything, been underacknowledged by penal theorists. Wacquant (Reference Wacquant2009) notes that “hyper‐incarceration” stimulated private‐sector involvement in the construction and management of prisons, as public authorities in the United States struggled to finance and contain the imprisonment binge. Certainly, private providers met the need for low‐cost, quick‐build prison places to deal with increasingly pressing population pressures within penal estates in the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom (Harding Reference Harding1997). However, prison privatization is aligned more broadly with neoliberal ideology than Wacquant seems to recognize, in its implicit critique of government competence, its regulation of labor in the interests of management (see Andrew and Cahill Reference Andrew and Cahill2007), and its assumption that the market is more cost effective, service oriented, and outcome driven than the state. By privatizing punishment services, governments are able to intervene in the sphere of criminal justice while offsetting or minimizing many of the costs and responsibilities of their interventions. The state both extends and retracts its punitive arm, sanctioning penal expansion but acting as commissioner rather than direct provider of services, so that its role is to “steer rather than row” the penal ship (Milward and Provan Reference Milward and Provan2000, 363).

Yet relatively little attention has been given to the impact of neoliberal penal restructuring either on prison staff or on prisoners themselves. In his analysis of the first privately run adult prison in Canada, Reference McElligottMcElligott 2007 describes correctional officers as “frontline workers,” subject to the same changes in labor practices that are reshaping the working lives of other frontline workers, namely, “contracting‐out, casualization, work intensification, and technological encroachment” (2007, 93). Emphasizing the complexity of the work of correctional officers, McElligott draws attention to a range of their occupational functions and practices: first, their position as gatekeepers to institutional and social resources and as mediators between “the state and its client/subject populations” (79); second, the importance of interpersonal skills for their daily interactions with their client group (i.e., prisoners); third, the centrality of “craft” (being “attuned to the tense dynamics of prison life” [91], to their daily practices); and fourth, the importance of “personal presence,” honesty, consistency, and “the deft use of formal and informal sanctions” (91) in maintaining everyday order and control.

This account of prison officer work is not in itself original. The importance in prisons of distributive fairness, respectful relationships, jailcraft, and the judicious use of power has been highlighted in a range of studies, from the classic ethnographies of prison life (e.g., Sykes Reference Sykes1958) to more recent and dedicated accounts of the roles and practices of prison officers (see, e.g., Liebling Reference Liebling2000, Reference Liebling2011; Crawley Reference Crawley2004). Emphasizing the importance in such work of peacekeeping and discretion, Reference LieblingLiebling 2000 describes officers as “specialists in mediation and arbitration” (2000, 347), engaging in a constant process of translating “rules into action.” This interpretative exercise (“where the ‘particular’ situation cannot be appropriately addressed by ‘the general’ rule” [344]), requires frontline staff to exercise judgment, based on established relationships with prisoners, in deciding whether to use authority, and what kind of authority to use. As Liebling (Reference Liebling2004) has also shown, the manner in which frontline staff use their authority has a profound impact on the prisoner experience—including levels of order, safety, distress, and suicide—and on the overall moral quality, or legitimacy, of penal institutions. In many respects, then, prison officers are much like other service workers or street‐level bureaucrats, but in extremely high‐stakes environments, with service users who are particularly dependent and whose relationship with the state is unusually complex.

For current purposes, the main relevance of McElligott's study is to suggest a framework for thinking about the consequences of private‐sector management for the daily life of prison staff and prisoners. McElligott (Reference McElligott2007, 85) argues that market logic entails “hostility to unions, bargaining rights, and any other impediments to the unrestrained exercise of management power” and that high levels of turnover and staffing efficiencies (in the form of fewer, less skilled, and poorly trained staff) diminish prison quality in a number of ways, undermining staff confidence and solidarity and—drawing on Liebling (Reference Liebling2000)—threatening precisely the kinds of relational qualities (such as trust, respect, and fairness) that maintain institutional stability. Yet McElligott's analysis of the causes and impact of privatization is somewhat partisan, in that it ignores the possibility that attempts to discipline recalcitrant staff cultures might be justified and that the introduction of private‐sector competition was shaped, in some countries more than others, by humanitarian as well as financial considerations.

In the United States, for example, regime improvement “was seen as a possible and desirable, but not essential, by‐product of better and more cost‐effective management” (Harding Reference Harding, Tonry and Petersilia2001, 272), whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, policy proposals in the late 1980s frequently referred to the possibility of improving service levels and standards (Moyle Reference Moyle1995; Harding Reference Harding, Tonry and Petersilia2001). One influential proponent of privatization in the United Kingdom noted that humanitarian arguments were “perhaps the most compelling” (Young Reference Young1987, 38; see also James et al. Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997). However, political ideology and pragmatic concerns with costs and chronic overcrowding were at least as important in the push for private‐sector competition as concerns about prisoner treatment and welfare (Ryan and Ward Reference Ryan and Ward1989; Jones and Newburn, Reference Jones and Newburn2005). Regime improvements were primarily conceived in terms of better working practices for staff and productive activities for prisoners (Windlesham Reference Windlesham1993), rather than staff‐prisoner relationships or humane treatment as such and much of the drive to privatize derived from a broader ambition to sidestep union resistance and reassert management control (Harding Reference Harding1997; Jones and Newburn Reference Jones and Newburn2005). This assault on the Prison Officers' Association was consistent with the then Conservative government's wider program of public‐sector reform and anti‐union legislation (Harding Reference Harding1997) and an assumption that private‐sector provision was “de facto preferable to public provision, whether or not prison populations and overcrowding were on the increase” (Jones and Newburn Reference Jones and Newburn2005, 73).

However, by the time that the United Kingdom's first private prison, HMP Wolds, was opened in 1992, in the wake of the Woolf Report on widespread prison disturbances two years earlier and as a result of a serious critique of standards and regimes for remand prisoners before that, greater emphasis was being placed on the importance of developing more positive and humane relationships between staff and prisoners. The invitation to tender for the running of Wolds drew on the Woolf blueprint, and the prison's guiding principles committed it to constructive relationships, reducing the frustrations of prison life and normalizing the environment as much as possible (James et al. Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997). Regardless of (or alongside) earlier, and more political, motivations, then, at the operational level, the first wave of private prisons in England and Wales represented a genuine attempt to provide a more humane correctional culture. According to an early evaluation (James et al. Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997), Wolds was fairly successful in meeting these aspirations. The prison was not without problems, most of which were linked to low staffing levels and staff inexperience. However, the great majority of prisoners reported positively on the prison, particularly with regard to staff‐prisoner relationships and the prison's less oppressive atmosphere. Compared to HMP Woodhill, a loosely comparable public‐sector prison, Wolds was rated more highly in areas such as the helpfulness of officers, fair treatment, living conditions, facilities, and food quality.

James et al.'s (Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997) evaluation remains the only serious sociological comparison of public‐ and private‐sector prisons in the United Kingdom to date (see also Bottomley et al. Reference Bottomley, James, Clare and Liebling1997).Footnote 1 Our previous research, in which we scrutinized private prisons within the terms of other studies, indicated that the treatment of prisoners in many private‐sector prisons is more benign and respectful than in most public‐sector prisons (for a précis of relevant research, see Liebling Reference Liebling2004, Reference Liebling, Byrne, Hummer and Taxman2008). At the same time, much like James et al. (Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997), many studies—including our own—have identified problems in the private sector that relate to thin staffing, high turnover, and the inexperience of the workforce (James et al. Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997; NAO 2003; HMIP 2007; see also McElligott Reference McElligott2007).Footnote 2 In particular, there appear to be persistent problems in private prisons in the areas of safety and security. Findings from Australia reveal similar patterns, that is, a more progressive staff culture than in the public sector, but dangerously low staffing levels (Moyle Reference Moyle1995) and deficiencies in staff professionalism (Rynne, Harding, and Wortley Reference Rynne, Harding and Wortley2008).

Critics of privatization argue that empirical evaluations are irrelevant in determining policy or settling questions about the legitimacy of privatization. Sparks (Reference Sparks, King and McGuire1994), for example, argues that private‐sector competition is a weak solution to much more significant problems of prison legitimation. For pragmatists like Harding (Reference Harding1997), purist positions of this kind risk providing an inadvertent defense of public‐sector squalor. Further, he argues, if accountability structures are sufficiently effective and private prisons are well regulated and administered, they can provide “a unique opportunity to raise standards and increase accountability across the total prison system” (Harding Reference Harding1997, 31). Given current policy currents in the United Kingdom and other jurisdictions—among which is a persistent belief in the inherent superiority of private‐sector management practices—we believe that too much is at stake to leave the debate free of scrupulous, empirical study. Many governments promote the idea of evidence‐based policy making, yet little is known about the relative strengths and weaknesses of state‐managed and privately managed prisons, about which forms of private‐sector imprisonment have more interior legitimacy, or, indeed, about the wider implications of contracting out state services to nonstate organizations or competing penal services. It is incumbent upon researchers, through combining reliable survey data with in‐depth qualitative data, not only to provide meaningful measures of differences between public‐ and private‐sector institutions, but also to explain them. As well as some critical policy implications, there are important managerial lessons to be drawn from the privatization experiment and broader critical sociological insights to be gained from delving deeper into the consequences of different varieties of institutional provision.

This article reports the findings of a detailed attempt to explore these issues in a systematic manner through a dedicated and independently funded study of public‐ and private‐sector corrections.Footnote 3 Drawing on qualitative and quantitative data from five private‐sector and two public‐sector prisons in England and Wales, including two closely matched pairs of public‐ and private‐sector establishments, it describes and explains differences in three aspects of prison quality of life and culture that are particularly salient to debates about neoliberal reform in the domain of punishment and beyond: first, the quality of relationships between frontline staff and prisoners; second, levels of staff professionalism (or jailcraft); and third, the manner in which prisoners experience the deployment of state authority.

Supporting findings in other jurisdictions (see Rynne, Harding, and Wortley Reference Rynne, Harding and Wortley2008), the article highlights the importance of staff professionalism in determining prison quality, particularly in shaping the way that staff use their authority and in mediating the attitudes of prison staff and their ability to deliver regimes that are fair, safe, respectful, reliable, and responsive. In this regard, the article argues that there are some characteristic strengths and weaknesses in both sectors. In the public‐sector prisons, standards of competence and professionalism were high, but negative staff attitudes placed limits on levels of care, respect, and humanity experienced by prisoners. In the private sector, less‐unionized, less‐experienced, and leaner workforces manifested themselves in very different levels of quality, both high and low. In both cases, however, these underlying factors—concomitant features of privatization—meant that private‐sector prisons tended to manifest weaknesses in the areas of security, safety, and policing. In this respect, despite the high quality of some private‐sector prisons and persisting cultural problems in the public sector, there are serious risks in the private‐sector staffing model of low pay and thin levels of officer deployment—a model that is increasingly being emulated by the public sector and that may characterize privatized areas of public service more widely.

Data and Methods

The present analysis draws on data collected as part of a broader study of values, practices, and outcomes in public and private corrections. A key aim of the study was to provide the kind of qualitative insight into the black box of culture, staff practices, and staff‐prisoner dynamics that has been absent from most public‐private evaluations, alongside more measurable indicators of difference (although see James et al. Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997; Rynne, Harding, and Wortley Reference Rynne, Harding and Wortley2008). Our original research design therefore comprised an ethnographic and survey‐based comparison of two matched pairs of public‐sector and private‐sector establishments.

Advice on which prisons were comparable was taken from senior practitioners in both sectors, with the eventual matches agreed on by both groups. Our criteria for matching prisons were function (i.e., security level), age, size, and official performance level, with the aim of exploring differences in practices, relationships, and moral quality between apparently similar establishments, rather than conducting an evaluation based on matched prisoner characteristics.Footnote 4 We initially planned to include prisons that were relatively well regarded (on the grounds that this would facilitate access and publication in this contested field), and to exclude one prison known to be particularly expensive in terms of its cost per prisoner place. Following the selection process, access was successfully negotiated with two local prisons,Footnote 5 Bullingdon (public sector) and Forest Bank (private sector), and two category‐B training prisons, Garth (public sector) and Dovegate (private sector).Footnote 6 The research team spent several weeks in each of these establishments between September 2007 and November 2008, during which time its members were given keys and allowed unaccompanied access to all areas of each prison.Footnote 7 Further details on these prisons, as they were at the times we were present in them, can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Details of Matched Prisons in the Study

| HMP Forest Bank | HMP Bullingdon | HMP Dovegate | HMP Garth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector/company | Private, Kalyx | Public | Private, Serco | Public |

| Function | Local prison | Community prison a | Category‐B training prison | Category‐B training prison |

| Operational capacity | 1,124 | 994 | 860 | 847 |

| Year of opening | 2000 | 1992 | 2001 | 1988 |

| Fieldwork period | Sept–Oct 2007 | April–May 2008 | Nov 2007–Jan 2008 | Sept–Nov 2008 |

a Although Bullingdon described itself as a community prison operating “as an adult male Cat C training prison with a Cat B local function” (http://www.hmprisonservice.gov.uk), it was, in effect, a local prison taking convicted and unconvicted prisoners from the nearby courts while also holding category‐C sentenced prisoners. In Prison Service performance comparisons, it is grouped with local prisons and can certainly be compared with Forest Bank, which was of the same security level and also held a mixture of sentenced and unsentenced Category‐B prisoners and a number of Category‐C prisoners.

Supplementary data (prisoner, staff surveys, and a small number of interviews) were collected at three other private‐sector prisons: Rye Hill (category‐B training prison), Lowdham Grange (category‐B training prison), and Altcourse (local prison) (see Table 2).Footnote 8 The inclusion of Rye Hill was opportunistic, the outcome of an invitation from the Office for National Commissioning to use our staff and prisoner surveys to assess how the prison was performing at the end of its rectification notice.Footnote 9 Lowdham Grange and Altcourse were incorporated into the study primarily because prisoners in our main research sites consistently referred to their quality and because we were keen to see what the best of the private sector might look like (especially once it became clear that our two original private‐sector prisons were not performing as well as we—and others—had expected).Footnote 10 Given the difficulties of securing access to private‐sector prisons and the chance of being able to broaden the scope of our study, the fact that the inclusion of the additional private‐sector prisons created some asymmetry in the research design was considered a worthwhile departure from the original plan. The result is a study that comprises a comparison of four matched prisons, while allowing further insight into the strengths, weaknesses, and characteristic features of almost half the private‐sector prisons in England and Wales at the time of the fieldwork.

Table 2. Additional Private Prisons Included in the Study

| HMP Rye Hill | HMP Lowdham Grange | HMP Altcourse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sector/company | Private, G4S | Private, Serco | Private, G4S |

| Function | Category‐B training prison | Category‐B training prison | Local prison |

| Operational capacity | 664 | 690 | 1,324 |

| Year of opening | 2001 | 1998 | 1997 |

| Fieldwork period | Sept 2008 | Jan 2009 | April 2009 |

A combination of research methods was employed, including interviews with prisoners, uniformed staff, and managers, observations of management meetings, adjudications, and staff‐prisoner interactions, and the distribution of quality‐of‐life surveys to 1,145 prisoners and 957 staff in total (for further details, see Table 5 later in this article). The qualitative component of the study included efforts to observe how staff used authority and discretion, gauge staff dispositions and explore the relationship between their attitudes and behavior, interview prisoners and staff about their experiences in general, identify differences in management styles and structures, and explore values as well as practices within each organization. Interviews were conducted with 114 prisoners and 133 staff, sampled purposively in order to represent variables such as—for prisoners—wing, privilege level, prison experience, sentence length, ethnicity, and age, and—for staff—wing, seniority, experience, job function, and sex.Footnote 11 These interviews were semistructured and wide‐ranging, discussing issues such as staff‐prisoner relationships and perceptions of treatment and safety. Almost all viable interviews were fully transcribed and coded, based on a schema developed through a reading of the relevant research literature and according to themes that emerged during the fieldwork period—a form of adaptive theory (Layder Reference Layder1998) used by us and many of our colleagues in other research.

Prisoner perceptions of their quality of life were gathered using a version of the Measuring the Quality of Prison Life (MQPL) Survey: a 140‐item self‐completion evaluation instrument (for more detail on the origins and development of the survey, see Liebling Reference Liebling2004; Liebling et al. Reference Liebling, Hulley, Crewe, Gadd, Karstedt and Messner2011). The survey asked prisoners directly about their experiences of staff‐prisoner relationships, respect, safety, order, and other such aspects of prison life that they agree matter, rather than relying on management information and secondary indicators of such variables (cf. Logan Reference Logan1992).Footnote 12 For the purposes of this study, in light of previous research, and following our first phase of fieldwork, the survey was adapted to ensure that it captured various aspects of the craft of prison work, through the dimensions staff professionalism, organization and consistency, fairness, and bureaucratic legitimacy (see the Appendix for further details). This overall approach is consistent with what Reference LoganLogan 1992 describes as a “confinement model” of prison evaluation, in which prisons are assessed not via external outcomes or through dimensions that have a “hypothesized effect on some instrumental justification for imprisonment, such as rehabilitation or crime control” (1992, 580), but according to whether they are “competent, fair and efficient [in the] administration of confinement” (579).Footnote 13 The principles underlying this model of evaluation are especially appropriate in jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, where staff‐prisoner relationships are sincerely proclaimed to be at the heart of prison life (Home Office 1984) and senior practitioners have adopted the notion of moral quality (Liebling Reference Liebling2004) in their evaluations of prison performance.

Surveys were administered to a systematic stratified sample of prisoners—drawn from a printed list of each establishment's current prisoners—from all areas of each establishment in supervised focus groups of between eight and twelve prisoners, with two members of the research team present. Completion of the questionnaire was voluntary, confidential, and anonymous. Time was made available at the end of each focus group for prisoners to elaborate on their answers and discuss issues arising from the surveys or otherwise salient with the research team. The views of staff were gathered using a Staff Quality of Life (SQL) Survey developed in consultation with prison staff (see Liebling Reference Liebling, Byrne, Hummer and Taxman2008; Liebling et al. Reference Liebling, Hulley, Crewe, Gadd, Karstedt and Messner2011; Tait et al. forthcoming).Footnote 14 Thus, while our measure of outcomes is limited to institutional quality (rather than outcomes such as recidivism), our methods of evaluation are more meaningful and comprehensive than those used in previous studies (e.g., Logan Reference Logan1992) and there are some links between our dimensions of prison quality and other outcomes. The research is based on carefully devised and detailed surveys with prisoners and staff in areas of prison life that they have helped identify and on sustained ethnographic attention.

For current purposes, two further points are worth noting. First, prisons have local issues, histories, and specific preoccupations that shape their cultures and that cannot be controlled for statistically. Both of the main private‐sector prisons were on a self‐conscious trajectory of improvement, having emerged from periods during which there had been problems with control and safety and very high levels of turnover. Each had recruited senior managers from the public sector with briefs of stabilizing their establishment. In the two main public‐sector prisons, proposals for workforce modernization were generating considerable discontent among staff at the time of our research. Public‐sector local prison Bullingdon had recently been through a performance‐test process, in which fears about being taken over by a private company had led to significant transformations in the staff culture. Public‐sector training prison Garth was in a period of relative stability, but was very aware of the risks inherent in holding prisoners at the higher end of the security spectrum, with managers often noting that its population was “difficult and dangerous.” The time spent by the research team in each establishment enabled us to understand and take into consideration these contextual factors. Second, there are some unresolved questions about what is meant by the term “quality,” including the degree to which prisoners and staff can be regarded as objective evaluators of prison quality or whether staff perceptions of their working life should be seen as a quality measure. As we suggest elsewhere (Crewe, Liebling, and Hulley Reference Crewe, Liebling and Hulley2011), the relationship between staff satisfaction and outcomes for prisoners is not straightforward. It is important to know the reasons why staff are content, nervous, or cynical and this makes it all the more important to combine survey‐based evaluations with qualitative insight in prisons research.

Findings

Before focusing on the three main areas of interest, it is worth highlighting the overall pattern of results. In the survey‐based comparison of the matched pairs of prisons, the public‐sector establishments generally outperformed their private‐sector comparators on prisoners' perceived quality of life. In the comparison of the training prisons, of the twenty‐one dimensions (established through factor analysis combined with theoretical reflection and statistical retesting), Garth (T‐pub) scored significantly higher than Dovegate (T‐priv) on seventeen (at the p < .05 level), while Dovegate's scores were not significantly higher than Garth's on any of the dimensions. In the comparison of the two local prisons, Bullingdon (L‐pub) scored significantly higher than Forest Bank (L‐priv) on eight dimensions, while Forest Bank scored significantly higher than Bullingdon on none.

Data from the three supplementary private prisons complicate this picture of public‐sector superiority, in that Lowdham Grange (T‐priv) and Altcourse (L‐priv) consistently outperformed all the other training and local prisons, both public and private. In the comparison of all four training prisons, Lowdham Grange scored significantly higher than Garth (T‐pub) on nine of the twenty‐one dimensions and significantly higher than Dovegate (T‐priv) and Rye Hill (T‐priv) on nineteen of the dimensions. Rye Hill's scores resembled those of Dovegate, that is, they were relatively poor compared to the other training prisons and were poor in a similar way. In the comparison of all three local prisons, Altcourse (L‐priv) scored significantly higher than Bullingdon (L‐pub) on fifteen of the twenty‐one dimensions and significantly higher than Forest Bank (L‐priv) on nineteen of the dimensions. Neither Lowdham Grange nor Altcourse scored significantly lower than any other training or local prison, respectively, on any of the dimensions.

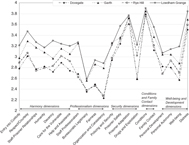

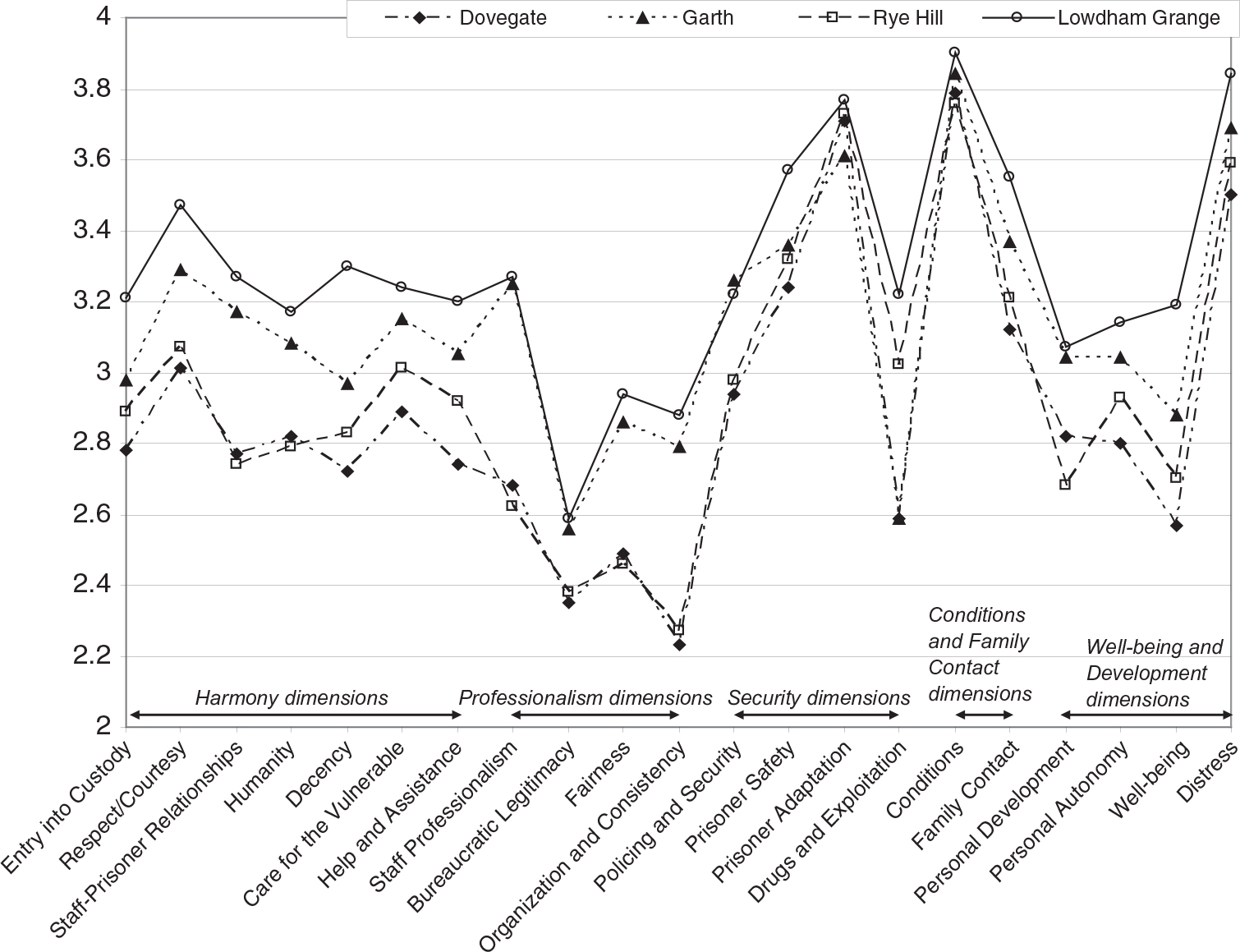

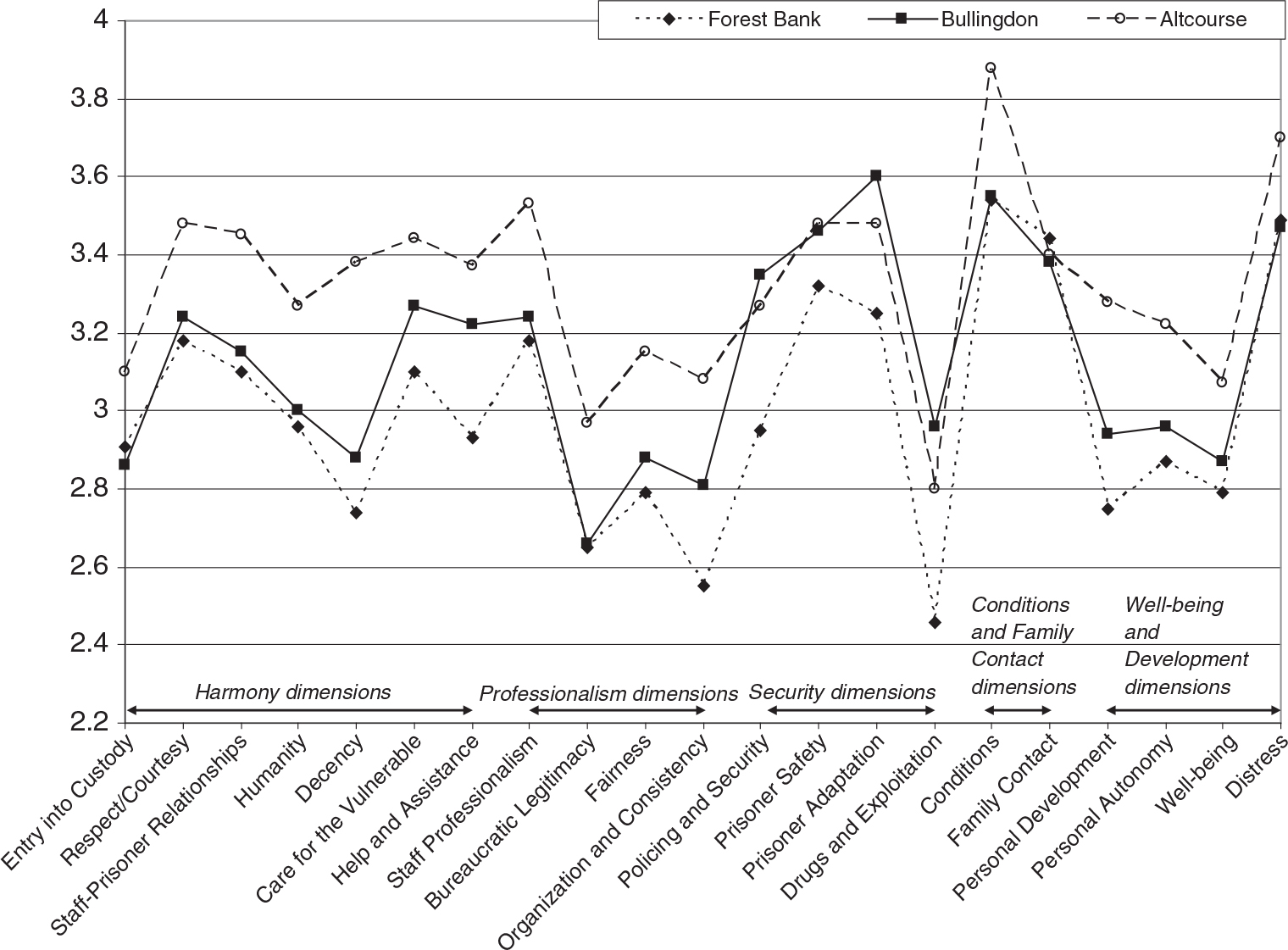

Figures 1 and 2 show the mean scores for each dimension for the three local prisons and the four training prisons, respectively. The dimensions are organized into five conceptual clusters or groups: harmony dimensions (which measure the most relational aspects of prison life), professionalism dimensions, security dimensions, conditions and family contact dimensions, and well‐being and development dimensions.Footnote 15 Each dimension comprises a number of individual items or statements that respondents scored on a range of Likert‐scale response categories from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The definitions, reliability scores, and item composition of these dimensions are provided in the Appendix (see also Crewe, Liebling, and Hulley Reference Crewe, Liebling and Hulley2011). Scores can range from 1 to 5, with 3 serving as the neutral mark (meaning that, on average, respondents rated the item in question neither positively nor negatively). Negatively worded items are recoded so that a higher score is always better than a lower score. Scores above 3 therefore represent a somewhat positive assessment and scores below 3 a somewhat negative assessment.

Figure 1. Mean Scores for All Quality of Life Dimensions for All Category‐B Training Prisons

Figure 2. Mean Scores for All Quality of Life Dimensions for All Local Prisons

To clarify the overall pattern of results, then—and as Figures 1 and 2 illustrate—both the highest‐performing and lowest‐performing prisons in each category were in the private sector.

In the sections to follow we describe and explain in more detail the findings that relate to three key and interrelated areas: staff‐prisoner relationships, staff professionalism (i.e., the craft of prison work), and the use of authority. In doing so, we focus initially on the two matched pairs of public‐ and private‐sector establishments in which we conducted sustained fieldwork. We then provide briefer comment on the prisons in which we collected supplementary data, which both complicates and corroborates our picture of the implications of privatization for prison quality and practice.

Staff‐Prisoner Relationships

In England and Wales, particularly, much of the debate about the relative strength of private‐sector imprisonment has focused on matters of interpersonal treatment. Private companies have self‐consciously sought to instill more positive and respectful staff cultures, in part by emphasizing the importance of interpersonal skills when training their workforces. Staff have been instructed by managers to call prisoners by their preferred names and not to see themselves as agents of punishment. Such measures are consistent both with official claims that one benefit of privatization is that it can stimulate new ways of providing public service (National Audit Office 2013), and—since much of the opposition to such humanizing reforms has come from the Prison Officers Association, both locally and nationally—with arguments that privatization represents an attack on the power of organized labor.

In interviews, prisoners in all the private‐sector prisons were less likely than those in the public‐sector establishments to say that they felt that staff looked down on them, judged them morally, or went out of their way to make their lives harder:

They're not making you feel like something that they walked in on their shoe. They're more prepared to listen to your side … and they will spend time listening and they seem to be less judgmental. (Prisoner, Dovegate)

They speak to you as you'd speak to somebody outside the jail; they show you a certain amount of respect and obviously expect to receive the same. … They don't look at you as in criminals and things like that; they just view you as normal people. … You're being punished by being here so they don't need to make it any harder. (Prisoner, Forest Bank)

In terms of staff philosophy, the private‐sector prisons conformed more closely to the dictum that prisons should be used as, not for, punishment. Uniformed staff in the private‐sector prisons more often talked about the importance of this distinction than those in the public sector, often referring to the emphasis that had been placed on it in their training. In Forest Bank (L‐priv) in particular, custody officers consistently used a language of helping and caring for prisoners. Here, then, the distance formed by contracting out the administration of state punishment seemed significant in creating a staff culture in which officers regarded themselves as deliverers of a service other than punishment itself. By contrast, in the public‐sector prisons, punitive and cynical views among officers were expressed far more frequently. There was a stronger belief that prisons did not provide a sufficient deterrent and, among some uniformed staff, a more disparaging and exclusionary attitude to prisoners:

I refuse to call a prisoner “Mr.” I'll call him by his preferred name and if that's James, it's James. But if a little scrotebag who's only just turned up on my wing expects me to call him by his first name, he'll be sorely. … I will use his surname until he's earned the right or the privilege. (Officer, Bullingdon)

Prisoners in the public‐sector prisons recognized that the respect they were given was to some degree conditional, both on their behavior and their submission to staff authority. “They want you to give them loads of respect before they treat you with respect” (Prisoner, Garth); “Basically if you are humble in here you'll be all right” (Prisoner, Bullingdon).

Given these differences in staff attitudes and because of previous research findings (James et al. Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997; Liebling Reference Liebling2004), the results from the prisoner surveys are striking. Table 3 shows the mean scores for the harmony dimensions for the two matched pairs of public and private prisons.Footnote 16 Garth (T‐pub) scored significantly higher than Dovegate (T‐priv) on all seven of the harmony dimensions, while Bullingdon (L‐pub) scored significantly above Forest Bank (L‐priv) on three. These results require further explanation.

Table 3. A Comparison of Mean Scores for the Matched Prison Pairs: Harmony Dimensions

While all four prisons were rated reasonably positively on the most superficial measures of staff courtesy and treatment—“Most staff address and talk to me in a respectful manner” (Garth: 70 percent; Dovegate: 63 percent; Bullingdon: 64 percent; Forest Bank 67 percent), and “Personally, I get on well with the officers on my wing” (Garth: 77 percent; Dovegate: 68 percent; Bullingdon: 77 percent; Forest Bank 72 percent)—prisoners in Dovegate (the private‐sector training prison) were significantly less positive than those in Garth (the public‐sector training prison) about most aspects of their relationships with staff and the humanity and respectfulness of their treatment. To give some examples, 39 percent disagreed with the item “I feel I am treated with respect by staff in this prison,” compared to 24 percent in Garth; and 26 percent disagreed with the item “I am being looked after with humanity in here,” compared to 11 percent in Garth.

Such results point to the fact that although prisoners in Dovegate (T‐priv) got on reasonably well with staff, these relationships were complex. Notably, this resulted in part from concerns within the prison about professional standards (i.e., inappropriate relationships between staff and prisoners, including staff corruption), which had made uniformed staff nervous about close interactions with prisoners—playing cards or pool, for example—or having informal conversations. Senior managers recognized that such anxieties meant that staff had backed off too far from prisoners, resulting in relationships that prisoners often described as shallow and superficial. For example:

Can you tell me what the relationships are like between staff and prisoners?

There ain't none …

How do they treat you?

They don't. They just unlock you and lock you up. (Prisoner, Dovegate)

Prisoners in the two private‐sector establishments complained less about staff attitudes than staff behavior. According to prisoners, officers were “nice people,” who were generally friendlier than those in the public sector, but they were not always able to answer queries (about sentence conditions or applications) or sort out problems (e.g., with visiting orders or phone credits). Many first‐line managers, as well as frontline officers, lacked the knowledge and confidence to deal with prisoners' problems and referred their queries and applications up the institutional hierarchy. Low staffing levels exacerbated these problems. Officers were often overstretched and were hampered by thinly staffed administrative departments. Indeed, officers in both private prisons described the difficulties of “trying to get the answers off various departments and trying to get things sorted” (Custody Officer, Dovegate) as being among their main frustrations:

What do you spend most time doing?

Chasing queries …; the phone could be engaged, the people might not be there, and while you're waiting to get hold of them again, you've got other queries from the inmates at the same time. … The prison seems to run at a minimum of staff. (Custody Officer, Dovegate)

Many prisoners in these private‐sector establishments accepted that staff were committed to trying to sort out their problems, but were overrun by requests. Others saw custody officers as lazy or two‐faced, resenting the fact that they were not receiving what they were entitled to, were given inconsistent information, or were promised things and then let down. Such frustrations were reflected in the survey data, in the training prisons particularly: 43 percent of prisoners in Dovegate disagreed with the item “When I need to get something done in this prison I can normally get it done by talking to someone face‐to‐face,” compared to 24 percent in Garth (T‐pub). Prisoners in Dovegate also reported significantly lower levels of trust in officers than those in Garth (56 percent disagreed with the item “I trust the officers in this prison” compared to 38 percent in Garth). As one Dovegate prisoner said: “You ask them to do something and they don't do it, so how can you trust them?”

Similar frustrations were expressed in the private‐sector local prison, Forest Bank, although with lesser intensity. Officers were seen as genuinely friendly, but lacking in knowledge: “Staff are great—just don't ask them to do anything” (Prisoner, fieldwork notes); as another prisoner summarized, “they get to know you, but they don't do things for you” (fieldwork notes). In both private‐sector prisons, then, many staff were benign and hard‐working, but their good intentions and positive attitudes were impeded by their relative inexperience and their thinness on the ground. As a result, prisoners experienced their treatment as relatively dis‐respectful (see Hulley, Liebling, and Crewe Reference Hulley, Liebling and Crewe2012), and reported lower levels of help and assistance than those in the two public‐sector establishments. Although this might have reflected better public‐sector provision in the areas of health care, detoxification, and offending behavior programs, staff expertise was also relevant. On the item “I have been helped significantly by a member of staff in this prison with a particular problem,” far more prisoners agreed in the public‐sector prisons than in their private‐sector comparators (56 percent in Garth compared to 40 percent in Dovegate and 58 percent in Bullingdon compared to 44 percent in Forest Bank).

Like prisoners, some senior managers blamed the quality of staff training for these problems:

They've got the balance wrong basically; they didn't give them the nitty gritty of prison law, the different things like that that you need to learn … and they concentrated too much on interpersonal skills which are really, really important, but it's got to be in balance. (Senior Manager, Forest Bank)

As we now explain, such deficiencies had wider relevance, not just for staff‐prisoner relationships, but in relation to levels of staff competence and professionalism more generally.

The Craft of Prison Work

Problems with levels of staff professionalism or jailcraft have been identified in previous studies of private‐sector prisons. Rynne, Harding, and Wortley (Reference Rynne, Harding and Wortley2008, 124), for example, describe staff inexperience as having compounded a serious prisoner disturbance in Queensland, Australia, while James et al. (Reference James, Bottomley, Liebling and Clare1997) identified insufficiently assertive and knowledgeable staff, plus poor training, as among the factors that offset the positive, helpful, and humane relationships that they found at Wolds (see also Moyle Reference Moyle1995).

In interviews, prisoners in the two main private‐sector establishments were often explicit in identifying a lack of staff professionalism as the key cause of their negative experiences, much of which they associated with high levels of staff turnover and what they assumed to be poor‐quality training and support. Senior managers were themselves candid in acknowledging that their staff were less good at following procedures than those in the public sector, that the quality of uniformed staff and middle managers was highly variable, and that high turnover was a major problem for their establishments. Private‐sector staff were open to changes in practices—far more so than in the public sector, according to senior managers who had worked in both—but often struggled to maintain and embed them:

Effecting change is tremendously easy here. The problem that we have is maintaining that change, so it's a bit of a Catch 22. If you want to change something it's easier [than in the public sector] to get staff on board. … but to maintain that piece of work … we have to continually revisit, revisit, revisit. (Unit Manager, Dovegate)

In contrast, prisoners reported the experience, knowledgeability, and general competence of public‐sector staff as an important strength of the sector. Uniformed staff in the public‐sector prisons were not always proactive in developing relationships with prisoners and they were considered less friendly and informal than private‐sector staff. Yet, on the whole, their interactions with prisoners were respectful and the competence with which they discharged their responsibilities offset their negative dispositions toward prisoners, to some degree.

This pattern was particularly evident in the two matched training prisons. Garth—the public‐sector training prison—prided itself on its professionalism, so that although, when interviewed, many uniformed staff expressed extremely negative attitudes about prisoners, in their interactions with them and in their use of power, they were generally competent, consistent, and fair. In the private‐sector comparator, HMP Dovegate—which scored notably and significantly lower than Garth on all four of our professionalism dimensions (see Table 4)—prisoners complained explicitly about levels of staff professionalism:

How confident are you that staff know what they're doing here?

I'm not.

Not confident at all?

I know they know how to turn a key, but on any other level than that I'm not too sure. (Prisoner, Dovegate)

To give examples from the survey data, compared to prisoners in Garth (T‐pub), prisoners in Dovegate (T‐priv) were significantly less likely to agree that staff had “enough experience and expertise to deal with the issues that mattered” to them (Dovegate 16 percent; Garth 39 percent) and that “staff treated prisoners fairly when applying the rules” (Dovegate 30 percent; Garth 46 percent). Furthermore, as suggested above, staff in Dovegate had struggled to establish appropriate professional boundaries, leading to a range of problems, including staff being manipulated by some prisoners and considerable confusion among others as to the boundaries of authority and friendship (see below).

Table 4. A Comparison of Mean Scores for the Matched Prison Pairs: Professionalism Dimensions

Table 5. A Comparison of Mean Scores for the Matched Prison Pairs: Security Dimensions

There were far fewer differences between the public‐ and private‐sector local prisons in relation to staff fairness and professionalism. However, in Forest Bank (L‐priv), prisoners expressed similar frustrations to those in Dovegate (T‐priv) about inconsistent decision making, deficits in staff expertise, and—as we discuss below—the feeling that staff were not always careful, confident, or judicious in using their power. Most significantly, in both private‐sector establishments, prisoners complained about a lack of certainty or consistency in the organization of the regime. They were less likely than prisoners in the public‐sector comparators to agree that the prison was “well controlled” (Garth: 45 percent; Dovegate: 27 percent; Bullingdon: 54 percent; Forest Bank: 34 percent), and to disagree with the statement: “There is not enough structure in this prison” (Garth: 38 percent; Dovegate: 59 percent; Bullingdon: 34 percent; Forest Bank: 48 percent). In interviews and discussions, the clarity and reliability of the regime (“knowing where you stand”) was consistently cited as a public‐sector strength, whereas prisoners in the private sector frequently complained about regime inconsistencies and organizational deficiencies. Again, these complaints highlighted the fact that the private‐sector workforce was less experienced, more tightly staffed, and less confident in using its power.

The Use of (State) Authority

This sense that public‐sector staff were better at creating a controlled environment reflected a broader issue relating to staff competence in the use of authority. Many of the themes that stood out most clearly in interviews and informal discussions related to the use of staff authority and such themes were also reflected in the survey data (see Table 5).

Prisoners in the two main private‐sector prisons often complained about both the underuse and overuse of power—“sometimes it's too strict, and sometimes it's not strict enough” (Prisoner, Forest Bank). In relation to the former, both private‐sector prisons felt somewhat undercontrolled, as prisoners described:

It is mayhem sometimes. … They have not got a lot of control. Certain wings, the officers are not running the wings. … There is no authority really. … They need more staff to keep on top of things. (Prisoner, Forest Bank)

The underuse of power was a particular problem in Forest Bank (L‐priv), where prisoners could sometimes ignore orders or back‐chat officers without consequences and some staff were reluctant to assert themselves when dealing with confident and knowledgeable prisoners. Staff underused their power in order to maintain good relationships, but this form of friendliness was perceived by prisoners as naïve and came at the expense of safety and control:

I think in order for staff to keep a good grip of the prison, or control over the prison, they can't try and be everybody's friend, there's got to be a cut‐off point. (Prisoner, Dovegate)

Prisoners wanted some power to flow and staff to fulfill their roles as figures of authority. Many expressed anxiety that officers were not fully in control of the wings and gave examples of seeing officers struggle to deal with violent or confrontational incidents.Footnote 17 While they liked the fact that staff were friendly rather than authoritarian, they were concerned that they could get themselves into trouble by not knowing the lines of appropriate conduct. They wanted clarity about what the rules were, when they would be applied, and with what consequences. Comments that the tone on the wings was “like a council estate” (Prisoner, Forest Bank) communicated a sense that the environment was too casual and permissive.

As a result of these deficits in supervision and control, prisoners in the private prisons felt less safe than those in the public‐sector prisons. They were more likely to agree with the item “Generally I fear for my physical safety” (Garth: 13 percent; Dovegate: 23 percent; Bullingdon: 17 percent; Forest Bank: 14 percent) and less likely to agree with the item “I feel safe from being injured, bullied or threatened by other prisoners in here” (Garth: 49 percent; Dovegate: 30 percent; Bullingdon: 52 percent; Forest Bank: 25 percent). Prisoners in the private‐sector establishments were also significantly more likely to agree than those in the public sector that staff turned a blind eye when prisoners broke rules, that staff were reluctant to challenge prisoners, and that the prison was run by prisoners rather than staff (see Table 6, which shows the results for all the items in the policing and security dimension).

Table 6. A Comparison of Mean Scores for the Matched Prison Pairs: Policing and Security Dimension and Item Scores

Many of these issues were manifested in the problems that Forest Bank (L‐priv), in particular, was experiencing in relation to the availability and consequences of drugs within the prison. Lacking in jailcraft—for example, failing to notice or act when large numbers of prisoners were congregating in specific cells—staff struggled to manage victimization and trade during association periods and prisoners in Forest Bank were significantly more likely than those in Bullingdon (L‐pub) to say both that the level of drug use in the prison was “quite high,” and that drugs caused a lot of problems between prisoners.Footnote 18

Managers in the private prisons admitted that having an inexperienced workforce, which lacked confidence in the deployment of power, had a deleterious impact on security, safety, and control. “There is no knowledge anywhere,” said one of Dovegate's senior managers. Describing his initial time on post a few months earlier, he explained that “security was hopeless [and] staff were frightened to tackle prisoners.” In both establishments, senior managers noted that wing staff too often dealt with prisoner misbehavior by submitting security reports rather than using informal authority or the incentives and earned privileges (IEP) scheme. As a result of such problems, both private‐sector establishments had brought in experienced ex‐public‐sector managers to reinforce the basics. In Forest Bank, for example, officers had been given refresher training on making eye contact and stopping prisoners from overstepping the line.

At the same time, prisoners in both private‐sector establishments also complained about power being overused in particular ways: staff too often resorted to formal disciplinary measures without forewarning prisoners and giving them a chance to rein themselves in—“sometimes you don't even know what you've done. … they just come up to you and say you're on basic” (Prisoner, Forest Bank).Footnote 19 Authority was exercised in a manner that felt arbitrary, inconsistent, or naïve. One prisoner in Forest Bank (L‐priv) joked that “if you wanted to sell drugs you'd get away with it in here, but if you have a towel at the end of your bed you're gonna get a nicking.” Inexperienced private‐sector staff often employed a “stand‐back, jump forwards” use of power, in which they underenforced the rules for a period and then overreacted to a particular case. In Dovegate (T‐priv) in particular, prisoners complained that staff used their power needlessly or unpredictably in situations that could be resolved through talk. Some complained that custody officers talked to them using language or manners that were inappropriate given their position as authority figures: “They're in your face and that, [acting like] you're all outside or in a boozer or something” (Prisoner, Dovegate); “I wouldn't come up to you and go ‘turn that music down, you cunt’ and I don't expect that from some professional that's getting paid to be here” (Prisoner, Dovegate). Here, then, the malleability of the workforce and the absence on the landings of strong models of confident authority meant that management attempts to encourage staff to be more assertive in their use of power were misinterpreted in practice. Staff were overusing their power, to the detriment of interpersonal relationships.

The inability of frontline staff to manage prisoner behavior effectively through informal means led to a reliance on more extreme formal measures. First, at the time of our study, Dovegate had established a Re‐integration Unit (RUG) with a restricted regime for prisoners deemed to be engaging in antisocial behavior (e.g., involvement in bullying or the drug culture). Prisoners often described the RUG as “intimidating” and “illegal,” partly because decisions to allocate prisoners there did not require a formal adjudication process. In the words of one interviewee, the threat of the RUG put relationships “on a knife‐edge … they can come for you anytime and send you to the RUG based on anything.” Meanwhile, a large number of prisoners on all wings described being subjected to a form of double‐jeopardy in which, if found guilty on a disciplinary adjudication, their privilege level was downgraded when they returned to their wing in addition to their designated punishment. Prisoners accused staff of “making up their own rules” and being “a law unto themselves” and, compared to those in Garth—the public‐sector comparator—were significantly more likely to agree with the item “In general, I think the disciplinary system here is unfair” (Dovegate 48 percent; Garth 32 percent).

Authority was used in a different manner in the public‐sector prisons. In these establishments, prisoners complained about its overuse more often than its underuse. Public‐sector officers were often described as somewhat “heavy,” bullying, or provocative, and terms such as “firm but fair” signaled what could be a rather stern, austere form of policing. In contrast to the private sector, where prisoners generally attributed the overuse of power to staff inexperience, in the public sector they ascribed it to negative staff attitudes—punitive views and moral disapproval. However, as the following quotations suggest, alongside these criticisms, prisoners in the public‐sector prisons were more likely than those in the private‐sector prisons to report that the majority of officers exercised their authority professionally:

How do they use their authority here?

There are some officers that throw their weight around because they're in a uniform … but a lot of the officers don't, a lot of them are quite fair in how they treat prisoners. (Prisoner, Bullingdon)

I think the majority of them use [authority] quite well and they know we know they're in authority, they don't tend to preach it. … But there is some that really go over the top and they really make your life difficult. (Prisoner, Bullingdon)

Prisoners in the public‐sector prisons appreciated that there was generally clarity about rules and boundaries, that officers dealt with incidents swiftly, and that staff rather than prisoners controlled the wings. They were in no doubt that when officers underenforced the rules, they did so deliberately and that they could exert power if they wanted to: “They are not too quick to use their authority, but they will, there is no lack of authority within the staff body” (Prisoner, Bullingdon).

The Supplementary Prisons

The findings from the other privately run establishments—Rye Hill (T‐priv), Lowdham Grange (T‐priv), and Altcourse (L‐priv)—complicate any notion that one can generalize about the performance and practices of private‐sector prisons, either in general terms (see Table 7) or in the specific areas most relevant to wider debates about the impact of the privatization of public services.

Table 7. Prisoner Quality‐of‐Life Scores: Supplementary Establishments

Prisoners consistently evaluated Rye Hill poorly, in a pattern almost identical to that of Dovegate (T‐priv). As in the other poorly performing private establishments, prisoners described staff as friendly, but lacking in basic forms of knowledge and competence and very low in number. In contrast, Altcourse (L‐priv) and Lowdham Grange (T‐priv) consistently outperformed the other local and training prisons, respectively, in almost all areas. Both were characterized by the expected strengths of private‐sector prisons, with very few of the weaknesses. Unencumbered by some of the organizational features of most public‐sector prisons, in particular, powerful trade unions, which tend to promote an ethos of staff cynicism, staff‐prisoner relationships were more trusting, humane, supportive, and respectful than in comparable prisons (both public and private) without the deficits in consistency, predictability, and professionalism that were found in Dovegate (T‐priv) and Forest Bank (L‐priv). Because the turnover of uniformed staff was lower than in these weaker private‐sector prisons, wing staff had built up the kind of confidence, knowledge, and expertise that was lacking in Dovegate, Forest Bank, and Rye Hill. Indeed, Altcourse was rated significantly more positively than Bullingdon (L‐pub) on all the professionalism dimensions in the survey and Lowdham Grange was rated more positively than Garth (T‐pub) on all the professionalism dimensions (although not to a statistically significant degree). To give some particularly striking examples from these dimensions, 71 percent of prisoners in Lowdham Grange and 60 percent in Altcourse agreed that “Relationships between staff and prisoners in this prison are good” (Garth 46 percent; Dovegate: 37 percent; Rye Hill: 33 percent; Bullingdon: 54 percent; Forest Bank: 48 percent) and 59 percent of prisoners in both Lowdham Grange and Altcourse agreed with the item “The regime in this prison is fair” (Garth: 43 percent; Dovegate: 32 percent; Rye Hill: 28 percent; Bullingdon: 39 percent; Forest Bank: 38 percent).

Such results highlight the relative quality of the two high‐performing private prisons, Lowdham Grange and Altcourse, and the consistent superiority of these establishments compared to the two public‐sector prisons in our study should not be downplayed. However, it is useful to note the areas where they were least strong, relatively speaking, since this reveals some of the characteristic weaknesses of private‐sector prisons. Most notably, prisoners in Lowdham Grange (T‐priv) were marginally less positive than those in Garth (T‐pub) about issues of clarity, security, and staff experience. For example, for the item “Staff in this prison have enough experience and expertise to deal with the issues that matter to me,” 39 percent of prisoners in Garth expressed agreement compared to 34 percent at Lowdham Grange. These differences were small but indicative: senior managers in Lowdham Grange admitted that staff were relatively unsophisticated, while the prison's controller noted that “[staff] experience is gained by a lot of stumbles” (fieldwork notes).Footnote 20 Relatedly, uniformed staff in Lowdham Grange—who were less experienced than those in Garth—spoke of feeling isolated on their wings and somewhat intimidated by the number of prisoners under their watch, As a result, they underused authority somewhat, as reflected in less positive evaluations from prisoners compared to those in Garth in some specific areas, such as the items “Staff in this prison are reluctant to challenge prisoners” (p < 0.001) and “Staff respond promptly to incidents and alarms in this prison” (p < 0.05).Footnote 21 In some work areas, prisoners openly flouted minor rules in the presence of staff (eating toast and drinking tea underneath signs prohibiting them from doing so) and on the wings, powerful prisoners were able to exert their influence without staff seemingly being aware of what was occurring.

Overall, then, the domains of security and policing were areas where the high‐performing private‐sector prisons were least impressive in relative terms compared to the public‐sector establishments. Thus, even in private prisons with relatively experienced staff, the thin staffing levels that characterize profit‐making institutions, a relative absence of jailcraft, and a workforce that is less bonded to its occupation, seem to limit quality levels in certain areas.

Discussion

Empirical data alone cannot settle debates about the ethics of private‐sector involvement in incarceration. We do not wish to “play down the politics of privatization, to narrow it to an argument about measurable performance or efficiency” alone (Ryan and Ward Reference Ryan and Ward1989, 110). Critics of privatization are right to raise questions about the impact of private‐sector lobbying and capacity on prison policy, both domestically and internationally, and about the questionable (and increasingly eroded) distinction between the allocation and administration of punishment. We also recognize that evidence of quality and effectiveness might not influence political decision making, in relation to imprisonment or in related areas of public service provision, as much as ideological zeal or considerations of cost and capacity (Thomas Reference Thomas2005). At the same time, we concur with Harding's comment that the debate about prison privatization has “profound human connotations” (Harding Reference Harding1997, 24), making it vital to add some evidence of how experiences and outcomes differ between the sectors and why this might be the case.

Our research shows that there is no simple relationship, internally, between either the profit motive or public service and quality. We are not as confident as some scholars and commentators (DiIulio Reference DiIulio1991; Radzinowicz, quoted in Shaw Reference Shaw1992; Christie Reference Christie1993) that the notion of public service has ever been sufficient—or sufficiently enacted in practice (Ryan Reference Ryan1993)—to merit the faith that is sometimes placed in it. In the public sector, while a set of values including decency, probity, and (to some degree) social justice are declared at the most senior levels, many frontline staff are not signed up to this agenda, nor do the mechanisms currently in existence for managing prisons secure their translation into practice (Liebling Reference Liebling2004). As our data illustrate, uniformed staff are often confident and knowledgeable, delivering regimes that tend to be safe and reliable and exercising power in a manner that is relatively fair and consistent. These strengths help counteract staff attitudes toward prisoners that are often punitive, disrespectful, or indifferent, albeit only partially.

In the private sector, the situation is almost the reverse. Profit is the sine qua non of private‐sector involvement in punishment provision and is the primary discourse at very senior levels within the global corporations that compete to run prisons. Counterintuitively, staff attitudes toward prisoners in private‐sector establishments appear to be more benign than in public‐sector prisons. Yet our data demonstrate that the relationship between staff intentions and prisoner outcomes is far from straightforward. There are limits to what positive staff cultures can achieve when there are other problems linked to private‐sector staffing arrangements. A lack of experience, capability, and expertise among staff, thin staffing levels, and high turnover typically lead to weaknesses in private prisons in areas such as policing and control, organization and consistency, and staff professionalism.

These weaknesses, even when relative, are identifiable even in the best private‐sector prisons. Thus, while our study shows that there is considerable variation in quality within the private sector,Footnote 22 it also suggests that there are some general and significant risks in contracting out prisons based on a model in which staffing is lean and staff are relatively expendable. Cost might not be the only relevant variable here (while Altcourse—a consistently high‐performing prison since its opening [Harding Reference Harding, Tonry and Petersilia2001]—is an expensive establishment, in the sense that the cost charged to the state is relatively high, Lowdham Grange is not),Footnote 23 but cheaper private‐sector prisons seem particularly vulnerable to the weaknesses that we have identified.

Given the current financial climate and a political culture of economic rationalism, this is a worrying observation. Cost was the primary consideration in the recent award of two new private prisons in the United Kingdom and, as Harding (Reference Harding, Tonry and Petersilia2001, 299) notes, evaluations of cost have “played a disproportionate role” in both debates and research about prison privatization or, we would argue, prison life. A “race to the bottom” (Gaes Reference Gaes2005, 86) on cost is risky for both sectors. Likewise, there are considerable dangers in emulating the private‐sector model in the public sector. In the early days of privatization, the vision of proponents was that public‐sector prisons would import the most positive attributes of the private sector: innovative practices, more efficient staffing, and so on. In a period of hyper‐efficiency, it may be the flaws of private prisons that are duplicated and the strengths of the public sector that are stripped out: safe levels of staffing, with mature and experienced officers, who use their power professionally.

We are aware of the dangers of generalizing about prison privatization on the basis of data from a specific jurisdiction (Camp, Gaes, and Saylor, Reference Camp, Gaes and Saylor2002; see also Perrone and Pratt Reference Perrone and Pratt2003). At the same time, the resonances between our findings and the international literature give us confidence that we have identified some meaningful strengths, weaknesses, and paradoxes of public‐ and private‐sector imprisonment. Furthermore, these trends have relevance beyond correctional services. First, they suggest that staff professionalism—matters of craft, skill, and fairness—may be an overlooked strength of the public sector and a potential weakness of the private sector. High levels of professionalism are necessary, although not in themselves sufficient, to assure the quality of public services and there may be tradeoffs between the malleability of staff and the embedded forms of expertise that reflect a more organized, independent, and professionalized ethos as well as practices. Where private companies engender a service ethos that is either superficial or is embedded in the culture, yet hampered by problems with service delivery or distributional fairness, then overall performance is bound to suffer. In our study, prisoners identified a distinction between staff “being nice” and “being good” at their work (see McEvoy Reference McEvoy2003; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Capps, Carr, Evans, Lewin‐Gladney, Jacobson, Maier, Moran, Thompson, McEvoy and Newburn2003). This distinction will have relevance in all kinds of sectors where service users are relatively powerless and therefore rely on the sedimented knowledge and experience, as well as the social skills, of those who exercise power over them.

Second, our findings point to the possibility that, where frontline staff feel powerless or are undersupported (by peers or managers), their tendency is to underuse or abdicate power in the face of powerful and well‐informed service users or to overassert it to shore up deficits in legitimate authority. This will not be relevant in all domains of public service, but has clear implications for those in which staff have supervisory or protective functions or are tasked with making decisions that service users might dispute. Given the increasing privatization of the security industries and of a range of jobs that involve discretionary decisions about the allocation of scarce welfare resources, there are clear implications here beyond imprisonment.

Third, the delegation of state authority to nonstate agents and agencies may have the potential to de‐legitimate the state in quite different ways. In the public‐sector prisons, prisoners' sentiments about the illegitimacy of staff overusing their power were exacerbated by the belief that such acts were done in the name of the state. Conversely, when private‐sector staff failed to discharge their duties effectively, the main criticism aimed at them by prisoners was that they lacked the legitimacy of state authority. Such comments pointed not to the sensitivity of prisoners to the sector in which they experienced their punishment—on the whole, prisoners were unconcerned as to who delivered their sentence, so long as its delivery was decent. Rather, they illustrated the different levels at which legitimacy and compliance could unravel: in the public sector, when treated badly, prisoners were censorious about the official framework of punishment; in the private sector, they were disdainful of custody officers, their criticisms threatening the self‐legitimacy and confidence of these staff. Their disdain for the state in this case related to the abdication of control and accountability for a state‐owned responsibility.

Finally, there are some general lessons for neoliberal reform of public services. Just as privatization cannot be said to be either straightforwardly good or bad in terms of the prisoner experience, it also seems likely that public/private ownership is unlikely to always be the most salient variable in determining quality across a wider range of penal, social, and administrative services. Whether or not privatization and private‐sector competition assist in the delivery of progressive public services remains an empirical question, linked to national and local contexts. Our findings highlight some of the risks of underestimating the skills and professionalism that lead to good rather than poor quality service work, in the public penal sector and beyond.

Appendix: Definitions, Reliabilities, and Composition of Dimensions

Harmony Dimensions

Entry into Custody (α = .618)

Feelings and perceived treatment on entry into the prison.

| Item no | Item | Corr. |

|---|---|---|

| qq89 | I felt extremely alone during my first three days in this prison. | .464 |

| rq1 | When I first came into this prison I felt looked after. | .416 |

| rq79 | In my first few days in this prison, staff took a personal interest in me. | .364 |

| qq76 | When I first came into this prison I felt worried and confused. | .327 |

| rq128 | The induction process in this prison helped me to know exactly what to expect in the daily regime and when it would happen. | .312 |

Respect/Courtesy (α = .886)

Positive, respectful, and courteous attitudes toward prisoners by staff.

| Item no | Item | Corr. |

|---|---|---|

| rq80 | I feel I am treated with respect by staff in this prison. | .782 |

| qq117 | This prison is poor at treating prisoners with respect. | .709 |

| rq28 | Most staff address and talk to me in a respectful manner. | .691 |

| rq5 | Relationships between staff and prisoners in this prison are good. | .669 |

| rq67 | Staff speak to you on a level in this prison. | .651 |

| qq42 | Staff are argumentative toward prisoners in this prison. | .646 |

| rq18 | Personally I get on well with the officers on my wing. | .561 |

| rq96 | This prison encourages me to respect other people. | .533 |

Relationships (α = .867)

Trusting, fair, and supportive interactions between staff and prisoners.

| Item no | Item | Corr. |

|---|---|---|

| rq6 | I receive support from staff in this prison when I need it. | .723 |

| rq21 | Overall, I am treated fairly by staff in this prison. | .704 |

| rq15 | I trust the officers in this prison. | .687 |

| rq86 | Staff in this prison often display honesty and integrity. | .683 |

| rq50 | This prison is good at placing trust in prisoners. | .602 |

| rq68 | I feel safe from being injured, bullied, or threatened by staff in this prison. | .550 |

| rq88 | When I need to get something done in this prison I can normally get it done by talking to someone face‐to‐face. | .550 |

Humanity (α = .889)

An environment characterized by kind regard and concern for the person, which recognizes the value and humanity of the individual.

| Item no | Item | Corr. |

|---|---|---|

| rq52 | Staff here treat me with kindness. | .736 |

| rq22 | I am treated as a person of value in this prison. | .734 |

| rq24 | I feel cared about most of the time in this prison. | .716 |

| rq59 | Staff in this prison show concern and understanding toward me. | .709 |

| rq10 | I am being looked after with humanity in here. | .698 |

| rq14 | Staff help prisoners to maintain contact with their families. | .609 |

| qq116 | I am not being treated as a human being in here. | .593 |

| qq32 | Some of the treatment I receive in this prison is degrading. | .534 |

Decency (α = .636)

The extent to which staff and the regime are considered reasonable and appropriate.

| Item no | Item | Corr. |

|---|---|---|

| rq147 | This is a decent prison. | .559 |

| rq93 | I can relax and be myself around staff in this prison. | .460 |

| qq145 | Anyone who harms themselves is considered by staff to be more of an attention‐seeker than someone who needs care and help. | .327 |

| qq97 | Prisoners spend too long locked up in their cells in this prison. | .316 |

| rq129 | Prisoners are treated decently in the segregation unit in this prison. | .313 |

Care for the Vulnerable (α = .803)

The care and support provided to prisoners at risk of self‐harm, suicide, or bullying.

| Item no | Item | Corr. |

|---|---|---|

| rq131 | Anyone in this prison on a self‐harm monitoring form gets the care and help from staff that they need. | .644 |

| rq112 | The prevention of self harm and suicide is seen as a top priority in this prison. | .638 |

| rq144 | Victims of bullying get all the help they need to cope. | .613 |