Article contents

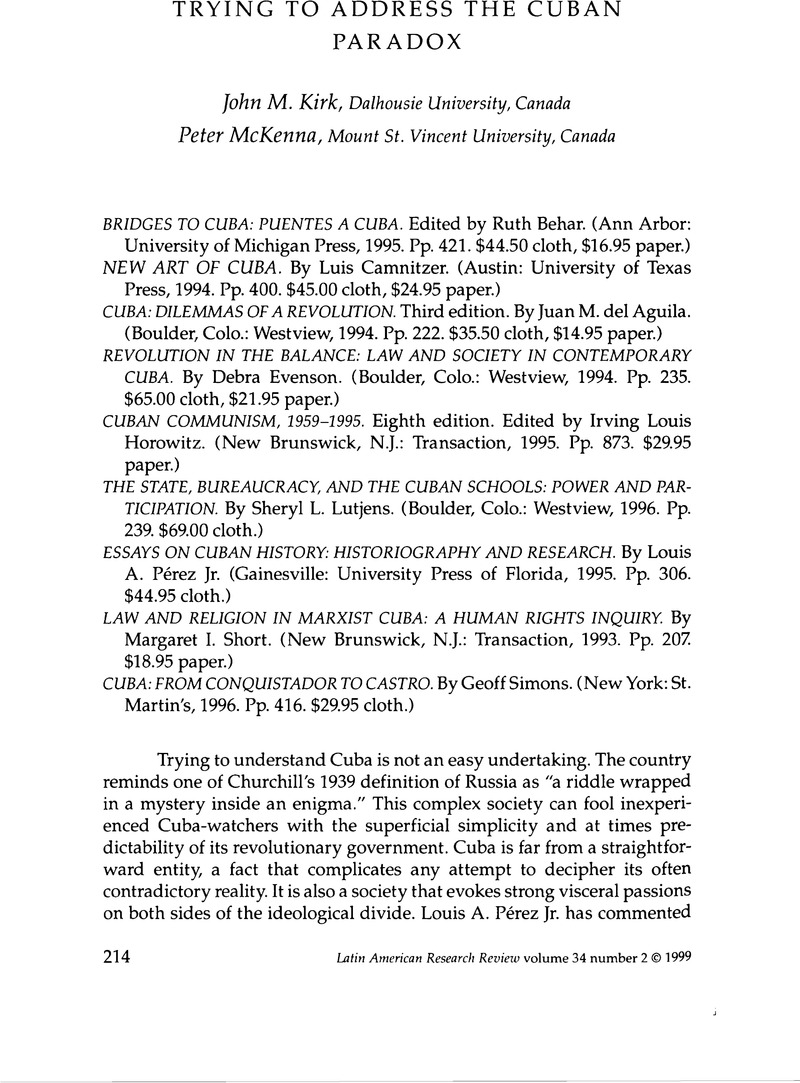

Trying to Address the Cuban Paradox

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1999 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. For a solid and well-researched treatment of the situation of women in Cuba, see the recent work by Lois M. Smith and Alfred Padula, Sex and Revolution: Women in Socialist Cuba (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

2. According to Short, “For three decades, Cuba has been one of the world's leading police states. The legal system was methodically transformed into an inherently atheistic and repressive force in revolutionary Cuba. …” She ends by quoting “Jesus of Nazareth” and requesting that the Cuban government, religious and secular groups in Cuba, and the international community call on Havana to respect human rights as outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “These internationally accepted standards, as well as the heart of a merciful God, cry out for an end to the persecution of theologically conservative Christians and other peaceful nonconformists in Cuba” (p. 151).

3. Three useful recent works with different approaches deserve mention. Although already significantly out-of-date, all three offer insightful analyses of the dilemmas facing Cuba as the new millennium approaches. In combination with the works of Cuban scholars noted in this review, they represent a useful starting point for assessing Cuba's current condition. See Tom Miller, Trading with the Enemy: A Yankee Travels through Castro's Cuba, 2d ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1996); Susan Eva Eckstein, Back from the Future: Cuba under Castro (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994); and Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Are Economic Reforms Propelling Cuba to the Market? (Miami, Fla.: North-South Center, University of Miami, 1994).

4. Of particular value in this regard are the following recent works: Julio Carranza, Pedro Monreal, and Luis Gutiérrez, La reestructuración de la economía: Una propuesta para el debate (Havana: Editorial Ciencias Sociales, 1995); Silvia Domenech, Cuba: Economía en período especial (Havana: Editorial Política, 1996); and La economía cubana en 1996: Resultados, problemas y perspectivas, edited by Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva (Havana: Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana, 1997). Also worth reading are two works by Juan Antonio Blanco: Tercer milenio: Una vision alternativa de la posmodernidad (Havana: Centro Félix Varela, 1995); and Cuba Talking about Revolution: Conversations with Juan Antonio Blanco by Medea Benjamín (Melbourne: Ocean, 1994). At the Universidad de Havana, a talented team of social scientists at FLACSO-Cuba have contributed to the analysis of change in Cuba, but their work has not been given the recognition that it deserves in the United States. Of particular interest is CartaCuba (1997): Essays on the Potential and Contradictions of Cuban Development. FLACSO-Cuba has also published eight “Documentos de Trabajo” on various topics: Cuba's “período especial,” Cuban quality of life, the impact of the economic crisis, biotechnology and environment, women and families, scientific development, economic restructuring, and foreign policy.

- 1

- Cited by