Article contents

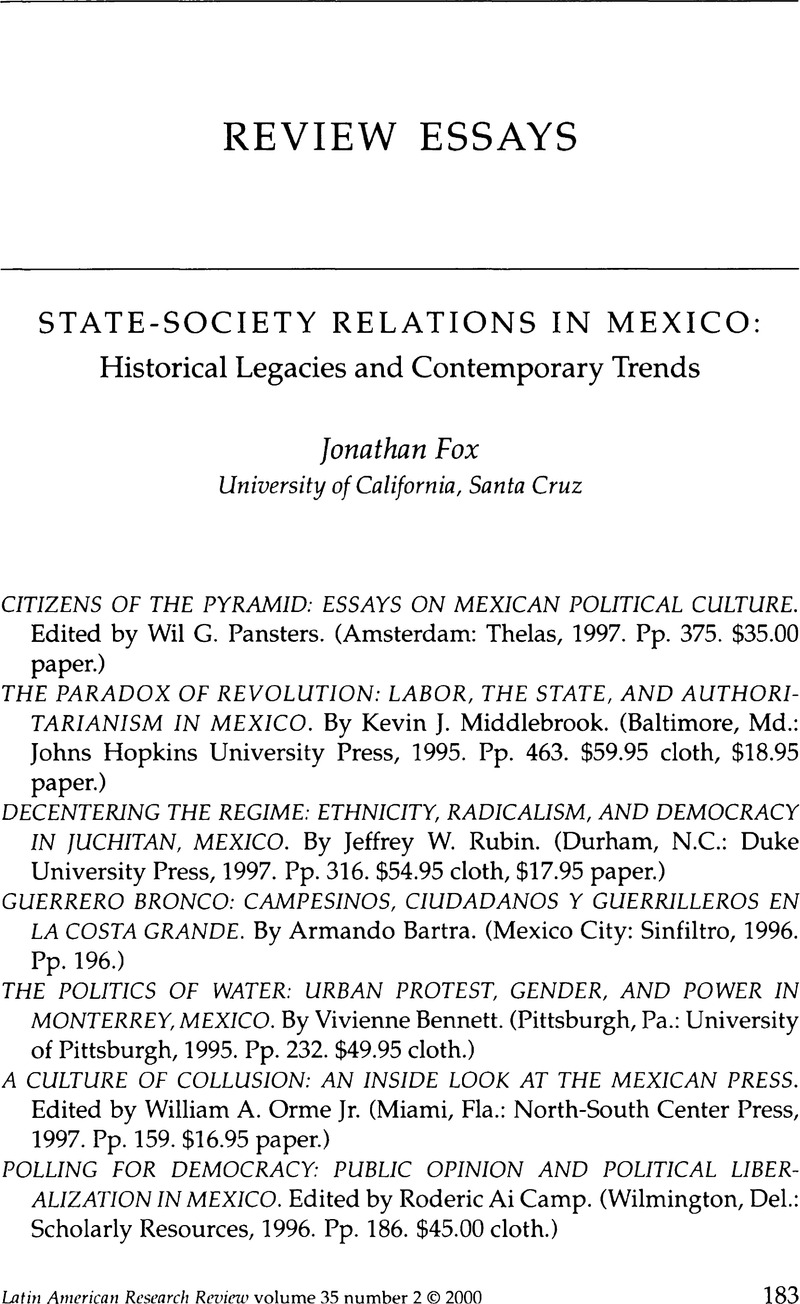

State-Society Relations in Mexico: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Trends

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2000 by the University of Texas Press

References

1. For one important effort to outline likely transition scenarios, see the introduction to Mexico's Alternative Political Futures, edited by Wayne Cornelius, Judith Gentleman, and Peter Smith (La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego, 1989).

2. In many ways, political scientists and sociologists are now catching on to what historians and anthropologists of Mexico have long emphasized: the centrality of regions for understanding politics.

3. See, among others, Cultura política y educación cívica, edited by Jorge Alonso (Mexico City: Miguel Angel Porrúa and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1994); Cultura política de las organizaciones y movimientos sociales, edited by Jaime Castillo and Elsa Patiño (Mexico City: La Jornada and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1997); El estudio de la cultura política en México: Perspectivas disciplinarias y actores políticos, edited by Esteban Krotz (Mexico City: CONACULT and Centro de Investigaciones e Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 1996); and Antropología política: Enfoques contemporáneos, edited by Héctor Tejera Gaona (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and Plaza y Valdés, 1996).

4. For an important interdisciplinary effort to reconceptualize the study of political culture, see Cultures of Politics, Politics of Cultures: Re-visioning Latin American Social Movements, edited by Sonia E. Alvarez, Evelina Dagnino, and Arturo Escobar (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1998).

5. Foweraker underscores Craig and Cornelius's view: “It is not beliefs that determine participation, but participation that determines beliefs, and it is the political learning achieved through adult activity in a union or neighborhood association that produces a sense of ‘mediated political efficacy”‘ (p. 227). See Ann Craig and Wayne Cornelius, “Political Culture in Mexico: Continuities and Revisionist Interpretations,” in The Civic Culture Revisited, edited by Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown, 1980), 363.

6. The essay builds on his insightful edited collection (with Ann Craig), Popular Movements and Political Change in Mexico (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1990).

7. Quoted in Suzanne Bilello, “Mexico: The Rise of Civil Society,” Current History 95, no. 598 (Feb. 1996):86.

8. Zapata's “Plan de Ayala” closed with the often-forgotten slogan “Reforma, libertad, justicia y la ley.” Note the revealing clash between Madero's and Zapata's conflicting under-standings of the rule of law in Gildardo Magaña's eyewitness report, “Emiliano Zapata Greets the Victorious Francisco Madero,” in Revolution in Mexico: Years of Upheaval, 1910–1940, edited by James W. Wilkie and Albert L. Michaels (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969).

9. Guillermo de la Peña also advocated the plural approach in “La cultura política en los sectores populares de Guadalajara,” Nueva Antropología, no. 38 (Oct. 1990):83–108, as cited in Héctor Tejera Gaona, “Cultura política: Democracia y autoritarismo en México,” Nueva Antropología, no. 50 (Oct. 1996):13.

10. Quoted in Jim Cason and David Brooks, “Señalan canadienses falta de libertad sindical en Mexico,” La Jornada, 24 Nov. 1998, p. 16.

11. Mexican electoral legislation requires local civic movements to affiliate with national political parties if they want to run for local office, a provision that often interferes with balanced relations between movements and parties.

12. See, for example, Los herederos de Zapata (Mexico City: Era, 1985). Unfortunately, only two of Bartra's essays have been translated into English so far: “The Seduction of the Innocents: The First Tumultuous Moments of Mass Literacy in Postrevolutionary Mexico,” in the pathbreaking Everyday Forms of State Formation, edited by Gilbert Joseph and Daniel Nugent, 301–25 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1994); and “A Persistent Rural Leviathan,” in Reforming Mexico's Agrarian Reform, edited by Laura Randall, 173–84 (Armonk, N.Y.: M. E. Sharpe, 1996).

13. For a new study of one of Guerrero's indigenous regions, see Jane Hindley, “Indigenous Mobilization, Development, and Democratization in Guerrero: The Struggle of the Consejo de Pueblos Nahuas del Alto Balsas against the Tetelcingo Dam,” in Subnational Politics and Democratization in Mexico, edited by Wayne Cornelius, Todd Eisenstadt, and Jane Hindley (La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego, 1999).

14. Recent coalition efforts to democratize the Costa Grande region's development process have expressed concern about the lack of “democratic culture” as a counterpoint to their own broad-based initiative to promote transparent, participatory, and accountable governance. See the main journal covering Guerrero's rural community-development movements, Autogestión 13, no. 4 (25 Nov. 1998).

15. Bennett builds on the literature of the middle to late 1980s regarding the relationship between “practical” and “strategic” gender interests, a discussion that has since evolved significantly. See, for example, Lynn Stephen, Women and Social Movements in Latin America: Power from Below (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998).

16. This mass organization, the Frente Popular “Tierra y Libertad,” focused mainly on land and housing issues. By the late 1970s, it could draw support from 5 to 10 percent of the city's residents, according to Bennett (p. 15). This once neo-Maoist organization later became a core group in the Partido del Trabajo. When the distraught former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari briefly sought refuge in one of their colonias after his brother was first arrested (during the ill-fated hunger strike), he symbolically underscored Solidaridad's project of creating direct state-society partnerships that bypassed the ruling party. He also highlighted the movement's limits.

17. For further discussion of the importance of the guaranteed secret balloting for revealing electoral preferences, see Jonathan Fox, “National Electoral Choices in Rural Mexico,” in Randall, Reforming Mexico's Agrarian Reform.

18. The 1988 election analysis is also undermined by McCann's confusion of Cárdenas's 1988 electoral coalition, the Frente Democrático Nacional, with the “Frente Cardenista,” a “parastatal party” that unilaterally changed its original name (Partido Socialista de los Trabajadores) to take electoral advantage of the presidential candidate's popularity (see pp. 91, 92).

19. Trejo Delarbre observes at the beginning of the volume that polling at its best captures “a snapshot of an instant in the life of a society” (p. 54). He avers that polls “are not capable of synthesizing all positions, beliefs, ideologies and knowledge that comprise the values of a society into one single opinion” (p. 39).

20. On women's movements, see Esperanza Tuñón, Mujeres en escena, de la tramoya al protagonismo: El quehacer político del Movimiento Amplio de Mujeres en México (1982–1994) (Mexico City: Miguel Angel Porrúa and Colegio de la Frontera Sur, 1997). On grassroots rural environmental movements, see the comprehensive Semillas para el cambio en el campo, edited by Luisa Paré, David B. Bray, John Burstein, and Sergio Martinez Vásquez (Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1997); Víctor Alejandro Payá Porres, Laguna Verde, la violencia de la modernización: Actores y movimiento social (Mexico City: Instituto Mora and Miguel Angel Porrúa, 1994); and Velma García-Gorena, Mothers and the Mexican Antinuclear Power Movement (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999).

21. Sociologist Luin Goldring is one of the few analysts to have framed the study of cross-border immigrant civic and political participation in hometown and national politics in terms of broader questions of state-society relations. See Goldring, “From Market Membership to Near-Citizenship: The Changing Politicization of Transnational Social Spaces,” in L'Ordinaire Latino-Americain (July–Dec. 1998), nos. 173–74 (published by GRAL and the University of Toulouse).

22. Analytical studies of the Catholic Church and grassroots movements in Mexico are remarkably rare. For an insightful comparison of the dioceses of Ciudad Juárez and the Oaxaca Isthmus, see Victor Gabriel Muro, Iglesia y movimientos sociales (Mexico City: Red Nacional de Investigación Urbana and Colegio de Michoacán, 1994).

23. Although chapters on Central America are included, the volume does not include a comparative focus, either cross-nationally or across sectors within Mexico. The chapters on Central America include América Rodríguez on pilot participatory education programs in El Salvador, which involved little NGO participation. Abelardo Morales and Carlos Soto assess environmental policy and government-NGO relations in terms of “concertación insostenible” (p. 255). Orlando Mendoza writes on the politics of food donations in Nicaragua and the displacement of native corn by wheat. The logic for including Central American cases appears to have been more geographic than analytical. The region's experience with NGO participation in the policy process is difficult to compare with that of Mexico because of the large role played by U.S. foreign aid, the legacy of the civil war, and the region's historically weak states.

24. They also draw readers' attention to one of the few studies of the urban popular movement that has taken appropriate account of the role of external social actors. See Oscar Núñez, Innovaciones democrático-culturales del movimiento urbano popular (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitano-Azcapotzalco, 1990). For comprehensive background on housing policy, see José A. Aldrete-Haas, La deconstrucción del estado mexicano: Políticas de vivienda, 1917–1988 (Mexico City: Alianza, 199).

25. See John Audley, Green Politics and Global Trade: NAFTA and the Future of Environmental Policy (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1997).

26. The coffee case is notable because it is the only sector where smallholder organizations that networked nationally managed to affect economic policy in the 1990s. See Luis Hernández Navarro and Fernando Celis, “Solidarity and the New Campesino Movements: The Case of Coffee Production,” in Transforming State-Society Relations in Mexico: The National Solidarity Strategy, edited by Wayne Cornelius, Ann Craig, and Jonathan Fox (La Jolla: Center for U.S.Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego, 1994); Richard Snyder, “After the State Withdraws: Neoliberalism and the Politics of Reregulation in Mexico,” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1997; and “After Neoliberalism: The Politics of Reregulation in Mexico,” World Politics 51, no. 2 (Jan. 1999): 173–204.

27. The Acteal massacre showed that Majomut faced a much greater threat from government-backed paramilitary organizations. Curiously, this study mentions the region's political and military conflicts only in passing.

28. The San Andrés Accords have been published in English for the first time in Cultural Survival Quarterly 23, no. 1 (Spring 1999), together with essays by leading Mexican advocates of indigenous rights.

29. For a conceptual discussion of pathways to variation, see Jonathan Fox, “How Does Civil Society Thicken? The Political Construction of Social Capital in Rural Mexico,” World Development 24, no. 6 (June 1996): 1089–1104.

30. For a persuasive application of the “political process” approach to Mexican state-society relations, see Maria Lorena Cook, Organizing Dissent: Unions, the State, and the Democratic Teachers Movement in Mexico (University Park: Pennsylvania State Press, 1996). Political identities organized around distinct regions within states can be crucial even for trade-union struggles that presumably involve broader shared interests. For example, the banner held by the Oaxaca contingent in a recent teachers' protest in Mexico City read “Regiones unidas jamás serán vencidas” (photo in La Jornada, 20 Jan. 1999, p. 44).

31. See Cornelius, Eisenstadt, and Hindley, Subnational Politics and Democratization in Mexico; and Opposition Government in Mexico, edited by Victoria Rodríguez and Peter M. Ward (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995).

- 6

- Cited by