No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

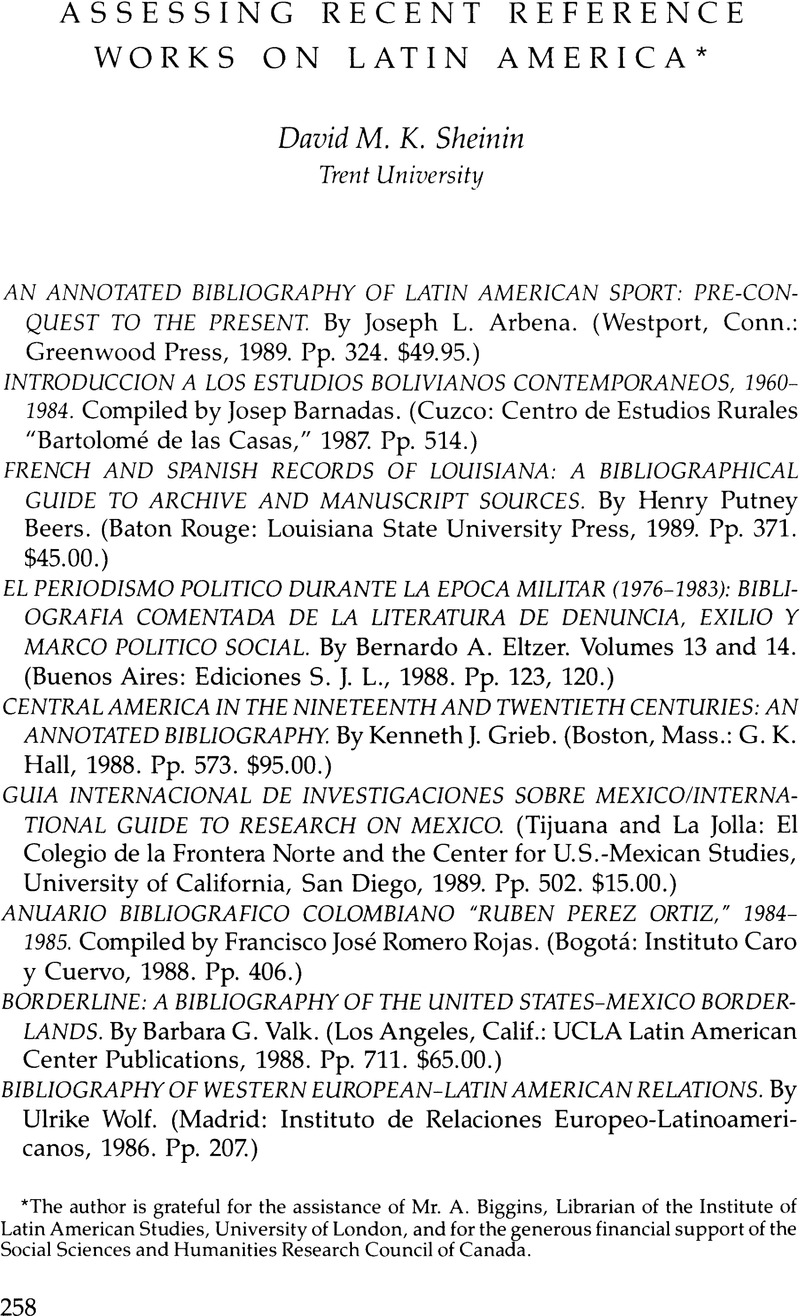

Assessing Recent Reference Works on Latin America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1992 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

The author is grateful for the assistance of Mr. A. Biggins, Librarian of the Institute of Latin American Studies, University of London, and for the generous financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

References

Notes

1. See Richard D. Woods, “Latin American Reference Books: An Underappreciated Genre,” LARR 24, no. 2 (1989):231–45; and Peter T. Johnson, “Facts, Statistics, and Bibliographies,” LARR 22, no. 3 (1987):253–70.

2. See John Simpson and Jana Bennett, The Disappeared (London: Robson Books, 1985); Horacio Verbitsky, Rodolfo Walsh y la prensa clandestina, 1976–1978 (Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Urraca, 1985); Jacobo Timerman, Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981); and Andrew Graham-Yooll, A State of Fear (London: Eland, 1986).

3. Hebe P. de Chocholous, “Argentina: necesidad de una bibliografía nacional,” Inter-American Review of Bibliography/Revista Interamericana de Bibliografía 38, no. 1 (1988):11–28.

4. See Hannah W. Stewart-Gambino, “New Approaches to Studying the Role of Religion in Latin America,” LARR 24, no. 3 (1989): 187–99; and Therrin C. Dahlin, Gary P. Gillum, and Mark L. Grover, The Catholic Left in Latin America: A Comprehensive Bibliography (Boston, Mass.: G. K. Hall, 1981).

5. David Cahill reviews some of the categories of Andean studies in which Peruvian theorists have influenced research directions and writing in Bolivia. See Cahill, “History and Anthropology in the Study of Andean Societies,” Bulletin of Latin American Research 9 (1990): 123–32.

6. Like the variety of subfields in border studies, relevant reference works demonstrate a comparatively high level of research on this region within the field of Latin American Studies. Valk cites academic debts to Jorge Bustamante's México-Estados Unidos: bibliografía general sobre estudios fronterizos (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1980) and Ellwyn Stoddard's Borderlands Sourcebook: A Guide to the Literature on Northern Mexico and the American Southwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1983). See also Laura Gutiérrez-Witt, “United States-Mexico Border Studies and Borderline,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 6, no. 1 (Winter 1990):121–31; Michael C. Meyer, “The Borderlands: An Historical Survey for the Non-Historian,” Journal of Borderlands Studies 1, no. 1 (Spring 1986):133–41; Maria Patricia Fernández Kelly, “The U.S.-Mexico Border: Recent Publications and the State of Current Research,” LARR 16, no. 3 (1981):250–67; Leslie Sklair, Maquiladoras: Annotated Bibliography and Research Guide to Mexico's In-Bond Industry, 1980–1988 (La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego, 1988); Arte Chicano: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of Chicano Art, 1965–1981, compiled by Shifra M. Goldman and Tomás Ybarra-Frausto (Berkeley: Chicano Studies Library Publications Unit, University of California, 1985); and United States-Mexico Border Statistics since 1900, edited by David Lorey (Los Angeles: University of California Program on Mexico, UCLA Latin American Center, 1990).

7. On recent reassessments of approaches to international relations in history, see Edmundo A. Heredia, “Historia de las relaciones internacionales: aproximación bibliográfica,” Inter-American Review of Bibliography/Revista Interamericana de Bibliografía 38, no. 3 (1988):339–53; Thomas G. Paterson, “Defining and Doing the History of American Foreign Relations: A Primer,” Diplomatic History 14 (Fall 1990):584–601; Emily S. Rosenberg, “Walking the Border,” Diplomatic History 14 (Fall 1990):565–73; and Akira Iriye, “Culture,” in “A Round Table: Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations,” Journal of American History 77, no. 1 (June 1990):99–107.

8. See Alfredo Mirandé, “Latinos in the United States: New Directions in Research and Theory,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 5, no. 1 (Winter 1989):127–44; Francesco Cordaso, The New American Immigration: Evolving Patterns of Legal and Illegal Emigration; A Bibliography of Selected References (New York and London: Garland, 1987); and Alex M. Saragoza, “The Significance of Recent Chicano-Related Historical Writings: An Appraisal,” Ethnic Affairs 1 (Fall 1987):24–63.

9. Gerhad Vinnai, El fútbol como ideología, translated by León Mames, 3d ed. (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1986 [1974]).

10. Although the sociological and historical literature on Hispanics in U.S. and Canadian professional sports remains small, some of the important theoretical examinations of Afro-Americans in sport are directly relevant to the professional careers of Latin American migrants and the literature on them. For example, the careers of boxers Roberto Durán, “Panama” Al Brown, and Eligio “Kid Chocolate” Sardiñas are explained in part by two theoretical works: Al-Tony Gilmore, “Jack Johnson, the Man and His Times,” Journal of Popular Culture 6, no. 3 (1973):496–506; and William H. Wiggins, Jr., “Jack Johnson as Bad Nigger: The Folklore of His Life,” Black Scholar 2, no. 5 (Jan. 1971):4–19.

11. Reference works on immigrant communities in Latin America also give little evidence of the role sport played in daily life. See, for example, Centro de Documentación e Información sobre Judaísmo Argentino “Marc Turkow,” Bibliografía temática sobre judaísmo argentino 4: el movimiento obrero judío en la Argentina, vols. 1–2 (Buenos Aires: Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina, 1987); and Dionisio Petriella, Los italianos en la historia de la cultura argentina (Buenos Aires: Asociación Dante Alighieri, 1979). The recurrence of sports associations in a recent listing of Argentine ethnic organizations hints at the prominence of sport in immigrant communities. See Rosa Majian, Guía de las colectividades extranjeras en la República Argentina, vol. 1, Europa occidental (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Culturales, 1988).

12. Adolfo Prieto, La literatura autobiográfica argentina (Buenos Aires: J. Alvarez, 1966); Gabriela Mora, “Mariano Picón Salas autobiográfico: una contribución al estudio del género autobiográfico en Hispanoamérica,” thesis, Smith College, 1971; and Raymundo Ramos, Memorias y autobiografías de escritores mexicanos (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1967).

13. Guillermo Lora, A History of the Bolivian Labour Movement, 1848–1971 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977); Sebastián Marotta, El movimiento sindical argentina: su génesis y desarrollo, vols. 1 and 2 (Buenos Aires: Lacio, 1960–61); Carlos Ibarguren, La historia que he vivido (Buenos Aires: Peuser, 1954); and José Carlos Mariátegui, Historia de la crisis mundial: conferencias (años 1923 y 1924) (Lima: AMAUTA, 1959).

14. Domitila Barrios de Chungara, Si me permiten hablar (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1978); Rigoberta Menchú, I, Rigoberta Menchú, an Indian Woman in Guatemala (London: Verso, 1984); and Sidney Mintz, Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1960).