1. Introduction

When the Psychology for Language LearningFootnote 1 (PLL) conference was started four years ago, we in Graz – as the hosts – chose the title ‘Psychology for Language Learning’ and decided not to add ‘and Teaching’. We felt it was too clumsy and concluded that it was obvious that teachers were included in this all embracing definition of the field. However, as time has passed, I have begun to reflect on whether or not this decision may have been a mistake.

Just as people tend to ‘gender’ certain nouns that are associated in people's minds primarily with one gender, thereby revealing an unconscious bias, e.g., ‘male nurse’, ‘female mechanic’, I wonder if this linguistic bias is also at play in the field of PLL. For example, motivation is assumed by many to refer first and foremost to learners, otherwise it is linguistically marked as ‘teacher motivation’. Similarly, work on cognition or identity is marked with ‘teacher’ to stress the population being investigated. As such, I have begun to ask myself whether a kind of inequality is at work in PLL regarding the relative status of teachers compared to learners (cf. Pewitt-Freilino, Caswell & Laakso Reference Prewitt-Freilino, Caswell and Laakso2011). Are learner needs, motives and their psychology being given priority over those of teachers? Or is this use of ‘teacher’ as an adjective simply being used to clearly define an area of research? My concern about this issue led us to conclude one of the books emerging from PLL1 with the statement, ‘We feel it necessary to explicitly stress that we see the term “language learning psychology” as inherently embracing the psychology of learners, teachers and collective groups involved in the language learning process’ (Gkonou, Tatzl & Mercer Reference Gkonou, Tatzl, Mercer, Gkonou, Tatzl and Mercer2016: 253).

In this talk, I want to examine possible reasons for the imbalance in the field and argue why this imbalance in respect to teachers urgently needs redressing from a practical as well as theoretical perspective. I will also elucidate an approach that highlights the role of teachers and offers a useful perspective for understanding the relational dimension of language learning and teaching psychology.

2. Setting the scene

2.1 Why is there such an emphasis on learners in PLL?

First, it is worth considering why the field has focused so strongly on learners. In part, this is understandable. Ultimately, the aims of the teaching profession are to help learners to learn to the best of their abilities. Learners are the reason teachers are employed and educational institutions exist. However, not all learners learn in the same way or experience the same degree of success. Hattie's (Reference Hattie2009) meta-analysis highlighted that the highest degree of variance in achievement is attributable to learner variables. Within second language acquisition (SLA), the field of learner individual differences (IDs) arose to better understand the variation in how learners (or groups of learners) acquire languages and their differing degrees of success. As Dörnyei (Reference Dörnyei2005: 2) explains: ‘IDs have been found to be the most consistent predictors of L2 learning success, yielding multiple correlations with language attainment in instructed settings within the range of 0.50 and above (cf. Sawyer & Ranta Reference Sawyer, Ranta and Robinson2001; Dörnyei & Skehan Reference Dörnyei, Skehan, Doughty and Long2003). No other phenomena investigated within SLA have come even close to this level of impact.’ As a result, it is natural that the field should strive to understand the psychology of those intended as the main beneficiaries of the teaching and educational processes, given their centrality to that process and their considerable impact on the relative success of its outcomes.

A particular development in the field of language education that may further have exacerbated the predominance of interest in the learner is the widespread engagement with the learner-centred movement (see, e.g., Nunan Reference Nunan1988; Tudor Reference Tudor1996; Spratt Reference Spratt1999; Benson Reference Benson, Burns and Richards2012). As a movement, it rightly drew much needed attention to learner individuality and learner needs, facilitating differentiated instruction and learner autonomy approaches. However, perhaps an unintended consequence of the pendulum swing may have been that in prioritising and foregrounding learner needs, we have neglected what Hattie (Reference Hattie2009) notes as being the second main source of variance, namely, the teachers themselves. In switching the focus from teacher instructional practices, we appear to have at the same time diverted our attention away from teachers as individuals with their own needs, motives and psychologies. Indeed, it has been suggested that a socialised discourse has emerged in which teachers are expected to put their learners first, ‘sacrificing’ themselves for the benefit of their learners (Nias Reference Nias, Vandenberghe and Huberman1999). This has led to a field reluctant to talk about teacher needs and their professional wellbeing, with only patchy research about the individuals who are the teachers themselves.

In research terms, overall, there is certainly nothing like the same developed broad body of research on teachers as individuals with complex, nuanced, unique psychologies as exists for learners, although as I will show in the next section, there are some notable exceptions. Traditionally, teachers have been seen in terms of ‘the learners’ environment’, rather than as agents in their own right (Leander & Osborne Reference Leander and Osborne2008 in Kalaja et al. Reference Kalaja, Barcelos, Aro and Ruohotie-Lyhty2016: 14). There may be pragmatic reasons for the lack of empirical research, such as time and access to busy in-service teachers (see, e.g., Hobbs & Kubanyiova Reference Hobbs and Kubanyiova2008). It is notable that the majority of work that does exist on teachers tends to focus on pre-service teachers. This may well be because they are the population that researchers most readily have access to, work with and are thus most interested in and who are able to benefit from interventions resulting from studies (see Mercer & Kostoulas in press). In addition, as Dörnyei (in press) notes, it is empirically difficult to reliably establish any chain of effect from teachers to learning outcomes and, indeed, any measurement of supposed teacher efficacy is fraught with difficulties and raises a number of political concerns. Surely, however, the field needs to understand all major stakeholders involved in language learning and teaching processes and this must include teachers, who have such a major impact on classroom life and individual learner success.

2.2 What do we already know about language teacher psychology?

As noted above, some excellent empirical work on teacher psychology in SLA already exists in two key areas: teacher cognitions and identity. In respect to language teacher cognition, a number of studies have contributed to our understandings about what teachers think and believe and how these cognitions may relate to their practices (see, e.g., Burns Reference Burns1992; Johnson Reference Johnson1994; Richards Reference Richards1996; Borg Reference Borg2003, Reference Borg2006; Barnard & Burns Reference Barnard and Burns2012). However, even considering the sizeable body of work on teacher cognition, Kalaja et al. (Reference Kalaja, Barcelos, Aro and Ruohotie-Lyhty2016: 12) conclude that, ‘compared with research on learner beliefs, research on teacher beliefs has made less progress over the past few decades in opening up new theoretical starting points, or challenging traditional definitions or research methodology’. Kubanyiova & Feryok (Reference Kubanyiova and Feryok2015) discuss the specific challenges facing the field of teacher cognition including problems in isolating individual components of teachers’ mental lives from other aspects of their psychologies and contextualised lives. They problematise the ‘limited epistemological landscape’ (p. 436) and the dominance of the cognitivist paradigm as evinced in the name of the field. Instead, they call for more ecological perspectives challenging traditional distinctions between cognition, affect and motivation as well as understanding the connections between ‘teachers’ mental lives’ and their situated classroom practices and learners’ lived experiences. This call for future developments in teacher cognition resonates with similar perspectives within the field of language learning psychology more broadly (see, e.g., Williams, Mercer & Ryan Reference Williams, Mercer and Ryan2015; Gkonou et al. Reference Gkonou, Tatzl, Mercer, Gkonou, Tatzl and Mercer2016).

The field of language teacher identity research is also a rich and vibrant area, as can be seen from two recent special issues (Varghese et al. Reference Varghese, Motha, Park, Reeves and Trent2016; De Costa & Norton Reference De Costa and Norton2017) and a collection of papers edited by Barkhuizen (Reference Barkhuizen2017). In this edited collection, Barkhuizen has outlined developments in teacher identity research, which have led to a diverse range of definitions and theoretical frameworks, although the clear preference in the field is for socioculturally informed perspectives. While many possible perspectives and definitions on self and identity exist, he offers a working definition of language teacher identity (p. x), which is extremely comprehensive and captures many of the elements noted as absent from teacher cognition research by Kubanyiova & Feryok (Reference Kubanyiova and Feryok2015), such as the blend of cognitive, emotional, social, ideological and historical dimensions as well as the blurry boundaries between an individual's inner and outer worlds and lives. He also sees identity not as a thing or an object but as something that is enacted, dynamic and multifaceted – a process or way of being. The collection of papers makes a deliberate attempt to be inclusive and sets a positive example for developments in PLL as a whole in terms of an openness to theoretical, methodological and empirical pluralism.

The largest body of work in respect to language learners’ psychologies considers their motivation. Yet, in comparison, there has only been a small fraction of that amount of work done with regard to language teacher motivation (see, e.g., Kassabgy, Boraie & Schmidt Reference Kassabgy, Boraie, Schmidt, Dörnyei and Schmidt2001; Kubanyiova Reference Kubanyiova, Dörnyei and Ushioda2009; Falout Reference Falout2010; Hiver Reference Hiver2013; Gao & Xu Reference Gao and Xu2014; Wyatt Reference Wyatt2015). Furthermore, when compared to the field of language teacher cognitions or identity work, the isolated studies of language teacher motivation cannot yet collectively be thought of as representing a developed, coherent body of work. Hiver, T. Kim & Y. Kim (in press) lament the absence of theoretical frameworks and clearly defined motivational constructs in many studies of language teacher motivation as well as a lack of clarity about how these diverse studies connect to each other and related work in the field of general education. A recent theoretically informed exception to language teacher motivation is Dörnyei & Kubanyiova (Reference Dörnyei and Kubanyiova2014) in which the authors describe how the L2 (second language) Self Motivational Framework can be employed with language teachers. Indeed, they argue for the importance of understanding teacher motivation before we can consider how teachers can foster the motivation and vision of their learners. As they explain (Dörnyei & Kubanyiova Reference Dörnyei and Kubanyiova2014: 123), ‘in order to be able to have something worthwhile to give to our students, we need to look after ourselves and nurture our own motivational basis’. However, as one anonymous reviewer of this manuscript astutely noted, there are challenges in researching teaching motivation and there is an important distinction to be made between motivation to teach and motivation for their jobs generally, which often include other less enjoyable aspects such as administrative responsibilities. Thus, although there are signs of a growing interest in language teacher motivation, the conclusion remains that ‘teacher motivation is still in its infancy relative to research on student motivation’ (Urdan Reference Urdan, Richardson, Karabenick and Watt2014: 228), especially in the case of language teacher motivation, and there remains much work still to be done.

Finally, to complete this brief overview, it is worth noting that there are also other areas of language teacher psychology in which isolated studies have been conducted, such as autonomy and agency (Sinclair, McGrath & Lamb Reference Sinclair, McGrath and Lamb2000; Lamb & Reinders Reference Lamb and Reinders2008; Feryok Reference Feryok2012; Kalaja et al. Reference Kalaja, Barcelos, Aro and Ruohotie-Lyhty2016; White in press), emotions (Cowie Reference Cowie2011; King Reference King, Gkonou, Tatzl and Mercer2016), resilience (Hiver & Dörnyei Reference Hiver and Dörnyei2015; Hiver in press; Kostoulas & Lämmerer in press), self-efficacy (Mills & Allen Reference Mills, Allen and Siskin2007; Mills Reference Mills2011; Wyatt Reference Wyatt2016), socio-emotional intelligences (Moafian & Ghanizadeh Reference Moafian and Ghanizadeh2009; Gkonou & Mercer Reference Gkonou and Mercer2017), and teacher IDs (Gurzynski-Weiss Reference Gurzynski-Weiss and Geeslin2013). See also Mercer & Kostoulas in press. Nevertheless, in terms of the depth and breadth of work as well as range of constructs examined in learner psychology, the imbalance in respect to teacher psychology remains self-evident.

3. Why we need to understand teacher psychology: The teacher and learner perspective

Yet, it is vital to understand teacher psychology for two key reasons: first, because teachers themselves are valuable stakeholders in the teaching and learning process in their own right (Holmes Reference Holmes2005), and second, because their psychologies and professional wellbeing have been shown to be connected to the quality of their teaching as well as student performance (e.g., Caprara et al. Reference Caprara, Barbaranelli, Steca and Malone2006; Klusman et al. Reference Klusmann, Kunter, Trautwein, Lüdtke and Baumert2008; Day & Gu Reference Day, Gu, Zembylas and Schutz2009). As Bajorek, Gulliford & Taskila (Reference Bajorek, Gulliford and Taskila2014: 6) explain, a ‘teacher with high job satisfaction, positive morale and who is healthy should be more likely to teach lessons which are creative, challenging and effective’. However, teachers are increasingly under enormous stress: there are record rates of burnout and teachers leaving the profession (e.g., Macdonald Reference Macdonald1999; Hong Reference Hong2010) and ‘70% of teachers and lecturers saying their health suffered because of their job’ (Lovewell Reference Lovewell2012: 46). As Hiver & Dörnyei (Reference Hiver and Dörnyei2015: 2) note: ‘teaching is the core profession in our global knowledge society; it is also clearly a profession in crisis – and [. . .] language education is no exception to this trend’. In addition to the challenges facing many teachers such as increased teaching complexity including the use of digital literacy skills, growing administrative tasks, challenging student behaviour, continual reforms, standardised testing, league tables (Kyriacou Reference Kyriacou2001; Day & Gu Reference Day and Gu2010; Rogers Reference Rogers2012), language teachers specifically often face additional stresses caused by the lack of job security typical in the profession (Wieczorek Reference Wieczorek, Gabryś-Barker and Gałajda2016) and the potential threat of low language skill self-efficacy and subsequent language anxiety, particularly for those for whom the language taught is not their first language (L1). As Horwitz (Reference Horwitz1996: 367) explains: ‘while a mathematics or history teacher can prepare the materials necessary to a specific lesson, language teachers must always be ready to speak the language in front of the class’. For these reasons alone, there would seem to be an urgent need for research to understand teacher psychology so we can appreciate how best to support teachers to ensure they not only ‘survive’ but ‘thrive’ in their professional roles (Castle & Buckler Reference Castle and Buckler2009: 4; Mercer, Oberdorfer & Saleem Reference Mercer, Oberdorfer, Saleem, Gabryś-Barker and Gałajda2016).

The second key reason why it is vital to investigate teacher psychology is because of the connection between teacher and learner psychologies, which are linked through processes of contagion (Skinner & Belmont Reference Skinner and Belmont1993; Dresel & Hall Reference Dresel, Hall, Hall and Goetz2013; Frenzel & Stephens Reference Frenzel, Stephens, Hall and Goetz2013). This means that teacher psychology can influence the psychology of the learners in the class – both as individuals and as a collective group. To appreciate how and in what ways interpersonal psychology can be ‘contagious’, we can draw on insights from various strands of neuroscience such as work on reciprocity, mirror neurons, theory of mind, and brain coupling (see, e.g., Baron-Cohen, Knickmeyer & Belmonte Reference Baron-Cohen, Knickmeyer and Belmonte2005; Frith & Frith Reference Frith and Frith2005; De Vignemont & Singer Reference De Vignemont and Singer2006; Mitchell Reference Mitchell, Slater and Bremner2011; Hasson et al. Reference Hasson, Ghazanfar, Galantucci, Garrod and Keysers2012; Cozolino Reference Cozolino2013). These studies show in particular how the emotions and motivation of a key member of a group, such as a teacher or a manager, can be ‘catching’ for those working with them. In general education, a number of studies exist which explicitly examine the interconnections between teacher and learner emotions, engagement, motivation and autonomy (e.g., Skinner & Belmont Reference Skinner and Belmont1993; Little Reference Little1995; Hargreaves Reference Hargreaves2000; Frenzel et al. Reference Frenzel, Goetz, Lüdtke, Pekrun and Sutton2009; Mifsud Reference Mifsud2011; Becker et al. Reference Becker, Goetz, Morger and Ranellucci2014). At present, the research remains unclear regarding possible factors which may mediate this relationship and the degree of conscious influence on the part of both teachers and learners in directing this relational crossover, but the psychological transfer between the two seems beyond doubt. It is also worth noting that relationships are bidirectional, which means that students are not passive recipients of teacher behaviours and student behaviour is also an important contributor to teacher's own subjective experiences of classroom life (see also, Friedman Reference Friedman, Vandenberghe and Huberman1999; Maslach & Leiter Reference Maslach, Leiter, Vandenburghe and Huberman1999; Spilt, Koomen & Thijs Reference Spilt, Koomen and Thijs2011). ‘The quality of the relationship between teacher and pupil can be one of the most rewarding aspects of the teaching profession, but it can also be the source of emotionally draining and discouraging experiences’ (Huberman & Vandenberghe Reference Huberman, Vandenberghe, Vandenberghe and Huberman1999: 3).

Thus, from both the teacher and learner perspectives, there are good reasons why it would be important to understand teacher psychology, firstly, in its own right, and, secondly, given its potential impact on teaching quality and learner psychology.

4. A theoretical perspective for researching teacher psychology

Having made the case for the need for more research into teacher psychology, I would like to use the second part of my talk to explore a theoretical perspective that I feel is ideally suited to this task.

4.1 Complexity perspectives in PLL

At present, perhaps one of the key theoretical frames being used in various areas of PLL is complexity theories (e.g., Mercer Reference Mercer2011a, Reference Mercerb; Dörnyei, MacIntyre & Henry Reference Dörnyei, MacIntyre and Henry2015; Gkonou et al. Reference Gkonou, Tatzl, Mercer, Gkonou, Tatzl and Mercer2016, Kostoulas & Stelma Reference Kostoulas, Stelma, Gkonou, Tatzl and Mercer2016; Sampson Reference Sampson2016), although other popular paradigms include various forms of sociocultural approaches as evinced by the conference programme. For those readers less familiar with the field of PLL, it is perhaps worth reiterating that PLL represents a field of inquiry and not a specific approach to investigating this area. Within applied linguistics, traditional notions of psychology have led people to perceive this area as being focused on cognitive and decontextualised mental world views of those involved in learning and, to a lesser extent, teaching a language. However, PLL embraces a range of perspectives due in part to changes including the social turn, attention to temporal and contextual dynamism, and holistic perspectives. As Dewaele (Reference Dewaele2014) stressed in his plenary at the first PLL conference, the field will benefit most from retaining theoretical and methodological plurality and, indeed, it is not my intention here to suggest the field should follow exclusively a complexity perspective. To do so would severely limit the growth of the field and the potential sophistication and depth of our understandings of language learning psychology. However, at present, complexity is the theoretical lens I am currently finding most helpful in furthering my own understandings and it is the one I wish to explore today in terms of its implications for research on teacher psychology.

Interest in complexity theories in SLA began in earnest in 1997, when Diane Larsen-Freeman introduced the idea of systems theory in her paper entitled ‘Chaos/complexity science and second language acquisition’. Since then, there has been quite a large body of complexity-led research in the fields of SLA and L1 acquisition. Even greater engagement with complexity perspectives across various areas of applied linguistics followed the publication of Larsen-Freeman & Cameron's (Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008) monograph: Complex systems and applied linguistics. Studies have been conducted in diverse areas of SLA including language, classroom interaction, motivation, self, autonomy, classroom dynamics, teacher cognition, innovation (see, e.g., Ellis & Larsen-Freeman Reference Ellis and Larsen-Freeman2006, Reference Ellis and Larsen-Freeman2009; Sade Reference Sade2009; Feryok Reference Feryok2010; Finch Reference Finch2010; Seedhouse Reference Seedhouse2010; Burns & Knox Reference Burns and Knox2011; Mercer, Reference Mercer2011a, Reference Mercerb; Dörnyei et al. Reference Dörnyei, MacIntyre and Henry2015; Kostoulas Reference Kostoulas2015; Svalberg & Askham Reference Svalberg, Askham and King2016). However, it is notable that the field of PLL has been particularly keen to embrace complexity perspectives and there are several possible reasons. Most notably, it is commonsensical that there can never be simple understandings of people as individuals or groups and any theory needs to be able to accommodate the real-life complexity of the human experience (cf. Kibler & Valdés Reference Kibler and Valdés2016). As Heft (Reference Heft2001: xxii) argues, ‘Psychology is the study of animate phenomena. Psychology needs to be built on a conceptual foundation compatible with the life sciences, and especially with the study of animals as organized, dynamic, adaptive beings, rather than on the mechanistic foundations of physical science’. The fields of SLA generally, and PLL specifically, have moved away from more ‘mechanistic, computer input/output’ thinking towards more organic and ecological perspectives (cf. Larsen-Freeman Reference Larsen-Freeman2016).

Humans and their psychologies display many of the characteristics of complex dynamic systems. In complexity theory, the term ‘complex’ has a specific meaning, which is distinct to the term it is frequently used interchangeably with, namely, ‘complicated’. As Mercer (Reference Mercer and King2016: 473) explains:

If something is complicated, it means that it may be composed of multiple components but these can be separated into distinct parts. An example often given is that of an airplane engine, which is highly complicated, but which can be taken apart and reconstructed by experts. In contrast, something that is ‘complex’ makes sense as a whole and cannot be taken apart and put back together again. Instead, its character emerges from the unique interaction of its multiple components, rather like a holistic, organic view of a human being.

Human psychologies also comprise many multiple, interrelated components and it is hard to meaningfully separate them, although research has done so and still does in order to make psychology researchable. The disagreements that often rage about the precise definition of and borders between constructs, as well as the nature of the relationships between them, is perhaps evidence of their unity.

Another key characteristic of a system is its dynamics. People's psychologies are inherently dynamic as people are continuously ‘becoming’ (van Lier Reference van Lier2004). There is never a finished state of who we are and who we feel and believe ourselves to be. In a complex dynamic system (CDS), the system is in a constant state of flux. This may lead to ‘dynamic stability’ (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008), which is not the same as being static. Instead, it means that the system may constantly be adjusting but may not change dramatically, although the potential for such radical ‘tipping point’ change is also present. As Nowak, Vallacher & Zochowski (Reference Nowak, Vallacher and Zochowski2005: 378) conclude: ‘The notion of personality implies some form of stability in thought, emotion and action. At the same time, human experience is inherently dynamic and constantly evolving in response to external circumstances and events’.

A CDS includes context as part of the system; it is not external to it. This implies that context is not viewed as influencing psychology from outside a person but rather it is seen as being an inherent part of the psychological system. This is perhaps for me the characteristic that distinguishes a complexity perspective most clearly from an ecological one, and so we find ourselves returning to the age-old structure–agency debates. From a psychological perspective, this line of thinking holds well when one considers the work of the symbolic interactionists (e.g., Mead Reference Mead1934) and social cognitive work by Bandura (Reference Bandura1986). In their work, they stress that individuals are not passive recipients of the influence of their social contexts but rather humans exercise their agency to differing degrees in how they subjectively make meaning out of their experiences and their contexts, while in turn influencing and being influenced by them. This implies a need to move away from thinking of contexts and cultures as being monolithic external objective variables affecting an internal inner world. Instead, contexts and cultures are subjectively interpreted in terms of the meaning for individuals. Individuals are seen as being connected across time and space to multiple contexts, past, present and future. These multiple contexts of one's life are all part of a person's psychological system; their frame of reference and ongoing psychology is defined by them and equally defines them. Contexts are within us (Mercer Reference Mercer and King2016). As such, when contexts change, so does the composition of the system. Depending on the significance of the contextual changes in the system balanced against the strength of attractor states for maintaining stability in the system, the psychological system as a whole can change or maintain dynamic stability.

Finally, one other key related characteristic is that a CDS self-organises and has decentralised causality. Self-organisation means that the system organises itself into adjusted states, rather than this organisation of the system being imposed by some external organising force (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008: 58). Such self-organising can lead to new emergent states, which have unique qualities that cannot be deduced from merely adding the separate parts together. Decentralised causality refers to the quality of a system in which change is not caused by a single component, directly and linearly affecting another component, but can emerge from changes in relations within the system. Perhaps an indication of the self-organising and emergent character of psychology can be seen in the ongoing debates about the sequence of cause-and-effect in the relations between cognition and affect and which has supremacy (see, e.g., Lewis Reference Lewis1995; Frijda, Manstead & Bem Reference Frijda, Manstead and Bem2000; Lewis Reference Lewis2000, Reference Lewis2005).

Finally, a point needing reiteratation is that not everything can be classed as a CDS, but rather a system must fulfil certain characteristic criteria, in order to be classified as one. A key challenge facing scholars researching from this perspective is deciding what can be defined as the ‘system’, where the boundaries of the system lie and whether indeed the system displays the characteristics needed to be understood as a CDS. Essentially, a system is a frame of perception and does not necessarily represent any real-world, bounded system (Checkland & Poulter Reference Checkland and Poulter2006). Traditionally, in psychology and ID research, constructs have been used which represent fragments of a person's entire psychology, defined to make researching psychology manageable, and varying in the degree to which they can be thought of as having phenomenological validity. All research needs to ‘reduce’ the whole of a person's psychology in some way to make it empirically manageable; however, the question is where and how one ‘fragments’ the system as a whole. From a complexity perspective, the rationale for setting boundaries on the system is less to do with obtaining strong statistical scores, as has often been the case with ID research, and more to do with a system's functional boundaries in an attempt to achieve a more holistic perspective. Nevertheless, we must be clear that researching psychology from a complexity perspective still inevitably involves a reduction of a more complex reality.

In the final part of this talk, I will look at two systems that I perceive in PLL, which can be thought of as to some degree ‘functioning as wholes’ (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron Reference Larsen-Freeman and Cameron2008). The first is the psychology of the classroom collective including teachers and learners. The second is the teacher's embodied psychology.

4.2 A relational perspective

Before I move on to look at these two systems in more detail, I need to outline briefly a particular approach to working with CDSs that I have found useful and which has led me to consider in more detail a relational view of language learning and teaching (Mercer Reference Mercer, Csizér and Magid2014a, Reference Mercer, Gregersen and MacIntyre2017). Networks have been proposed as one way of making complexity more manageable for research purposes while retaining the complexity and holism of a CDS (Mercer Reference Mercer, Dörnyei, MacIntyre and Henry2014b). They help us to make a system simpler to understand without making it unduly simplistic. Barabási (Reference Barabási2003: 238) claims that ‘Networks are the prerequisite for describing any complex system, indicating that complexity theory must invariably stand on the shoulders of network theory’. Essentially, networks are concerned with relationships between things, which are typically referred to as nodes. A node can be ‘any type of entity that is capable of having some sort of relationship with another entity’ (Borgatti & Ofem Reference Borgatti, Ofem and Daly2010: 19). An important dimension of network analysis involves not only examining the nature of specific relationships but also the structure of all the network relationships to understand the characteristics of the network itself (Kadushin Reference Kadushin2012). It is the structure of the network and how nodes are connected, which can either facilitate or hinder the ‘flow’ of things around the network. For example, in a language classroom, emotion could be thought of as flowing through the classroom social network. Depending on who is connected to whom and how, this emotional climate from one relationship/node can spread to influence the emotional climate of other parts of the network (see the related concepts of contagion and diffusion in Carolan Reference Carolan2014).

As an approach, network analysis foregrounds relationships. Typically, we talk about a CDS being ‘more than the sum of the parts’. In a network, the emergent characteristics of the system are defined as stemming from the interaction of multiple relationships, not components. As Gergen (Reference Gergen2009: 55) explains, it is more the case that ‘the whole is equal to the sum of its relations’. Such thinking transforms how we view components of a system, as Trueit & Doll (Reference Trueit, Doll, Osberg and Biesta2010: 136) argue: ‘the new found importance of relations and interactions in complex systems signals the limits of the concept of individualism’ (emphasis in the original). As will be seen in what follows, the focus shifts from looking at individual components of a system to looking at the relationships between parts of the system.

A relationship distinguishes between two nodes as well as connecting them and, as such, implies a certain distance between them (Donati & Archer Reference Donati and Archer2015: 18). From an empirical perspective, it suggests a need to understand the nodes involved in the relationship as well as the quality and character of the relationship itself. Relationships can be social, i.e., between people, but they can also exist between a person and the ‘nonsocial world’ (Donati & Archer Reference Donati and Archer2015). In other words, we can form relationships to places, ideas, concepts, artefacts etc. (see Mercer Reference Mercer, Csizér and Magid2014a, Reference Mercer, Gregersen and MacIntyre2017), but the relationships may differ in terms of reciprocity as noted by differences in prepositions describing relationships with people and relationships to non-social objects or concepts. Fundamentally, Burkitt (Reference Burkitt2014) argues that as socially situated beings, there is no non-personal way we humans can engage with the world, and it is impossible not to be in a relation to something. Donati & Archer (Reference Donati and Archer2015: 56) explain that ‘to say something or someone is social means that it is relational’ referring to the relations between self and otherness (including other people and things – everything that is not-I).

A key dimension of a relational perspective, as noted above in respect to discussions of context within the system, is the role of human agency. As reflective, sentient, agentic human beings, we are able to actively construct and subjectively think on a meta level about the relationships in our world in complex and, at times, unpredictable ways (Vallacher & Nowak Reference Vallacher, Nowak, Guastello, Koopmans and Pincus2009). This means relational perspectives must account for the human capacity for strategic behaviour and reasoning and the cognitive, affective and motivational character of human agency (Robins & Kashima Reference Robins and Kashima2008; Easley & Kleinberg Reference Easley and Kleinberg2010). In network analysis, other characteristics of the relationships themselves can be examined. These include the relational quality, valence, intensity, choice (or whether a social relationship is enforced such as in the case of teachers/learners), degree of closeness and multiplexity (whether the relationships have multiple strands such as knowing people in more than one relational role/context).

The growing interest in relational perspectives suggests that perhaps it is the relationship which should become the key unit of analysis and not individuals in isolation (see also Gergen Reference Gergen2009). Yet, rather than relations per se, it is perhaps more appropriate to think in terms of relating (see also Parks Reference Parks2007). Accepting that a CDS is in a constant state of flux means the relationships within in it are continually shifting and changing to differing degrees. Adding the human capacity for agency and reflection to this, it would be more appropriate to conceive of relating as an active, ongoing process, rather than thinking of relations as static entities. Relating is something people do consciously and unconsciously. Relationships are enacted and their qualities and positions in the system are continually emerging. Therefore, it might be more fruitful to work with the concept of active relating, rather than a view of relationships which may inadvertently imply something more static.

In what follows, I will use a relational perspective to reflect on two systems: the teacher within the classroom collective and the teacher's embodied psychology.

5. Relational perspectives on two systems involving the teacher

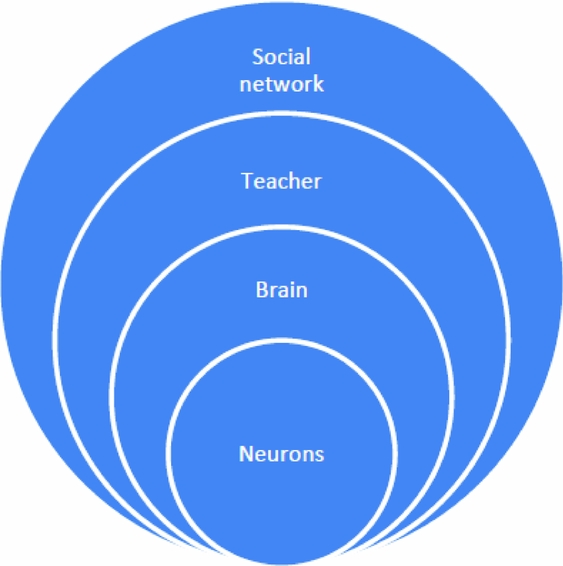

One characteristic in complexity is fractalisation and self-similarity across system levels. This refers to patterns in properties, structures and behaviours of systems, which can be similar across different levels of systems. A useful graphic frequently used is based on Davis & Sumara (Reference Davis and Sumara2006). The nested system view helps us to understand different scales of systems but also helps us see the levels at which fractal patterns could occur. The graphic should not imply nested hierarchical systems, although I fear it does for some. Rather, the boundaries between systems are permeable, open and fuzzy. The different systems merely represent different scales on which a system is defined and examined. As Davis & Sumara (Reference Davis and Sumara2006: 29) explain, the different systems can be distinguished according to their relative ‘size’ and ‘scope’, as well as to the different ‘pace of their evolution’.

Figure 1 gives one set of systems that are relevant to our discussions of teacher psychology. They reflect different degrees of granularity of systems involving the teacher. In terms of self-similarity of fractalised patterns, there seem convincing arguments for reflecting on teacher psychology in terms of networks of relationships. On the lowest level of granularity, we know from a convincing body of work that the brain can be thought of in terms of neural network structures (e.g., Jirsa & McIntosh Reference Jirsa and McIntosh2007). On higher levels of granularity in communities, we also know that there are many compelling arguments in favour of understanding social structures in terms of networks (e.g., Kadushin Reference Kadushin2012). From a fractals perspective on systems, this suggests a network perspective could be useful when looking at the individual psychology of the teacher as well as the collective psychology of the group including the teacher and learners.

Figure 1 Systems involved in teacher psychology (based on conceptual models in Davis & Sumara Reference Davis and Sumara2006)

5.1 Classroom as a CDS: Teacher at the heart

The first system that I will discuss is the language classroom community, which can be viewed as a collective psychology that functions as a CDS. However, it must be remembered that this represents an open system although we are placing conceptual boundaries on it for empirical and theoretical purposes. As van Lier (Reference van Lier2004: 194) reminds us: ‘learners spend an hour or so in the classroom, but before that they have been elsewhere, and after that they will go to other places. There is no doubt that their activities elsewhere have an effect on what happens in the classroom, and the same goes for the teacher.’ Benson & Reinders (Reference Benson and Reinders2011) have also highlighted the importance of understanding what happens ‘beyond the classroom’. As Stevick (Reference Stevick1980: 7–8) explains, a language class is one arena in which a number of private universes intersect with one another and it cannot really be thought of as separate or distinct to the individual participant's other worlds and lives.

Focusing on a collective view of classroom psychology highlights the inherently social and relational nature of language learning. When teachers and learners come together in a classroom, they do so in order to teach and learn together. As Farrell argues (Reference Farrell2015: 27), ‘Teaching is a relational act because it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate the people (teachers and learners) from the act (teaching and learning)’. Indeed, the learning of anything, but especially a language, is a social undertaking involving interpersonal connection. As Byrnes (Reference Byrnes, Arnold and Murphey2013: 225) says: ‘meaning-making with language is inherently social and involves another’. It is the social relationships in the classroom, which ‘orchestrate what is made available for learning, how learning is done and what we achieve’ (Breen Reference Breen and Breen2001: 131).

In Hattie's (Reference Hattie2009) meta-analysis of the most influential factors in learning, the teacher–student relationship comes high up on the list with an effect size of 0.72, far above other key variables such as motivation, which had an effect size of 0.49 in the original study. A quality teacher–student relationship is considered one of the most valuable resources in education (Pianta Reference Pianta1999) and has shown to be linked to a range of key desirable educational outcomes (Furrer, Skinner & Pitzer Reference Furrer, Skinner and Pitzer2014). In sum, ‘an extensive body of research suggests the importance of close, caring teacher–student relationships and high quality peer relationships for students’ academic self-perceptions, school engagement, motivation, learning, and performance’ (Furrer et al. Reference Furrer, Skinner and Pitzer2014: 102; emphasis in the original). As Palmer (Reference Palmer2007: 11) explains, ‘good teachers possess a capacity for connectedness. They are able to weave a complex web of connections among themselves, their subjects, and their students so that students can learn to weave a world for themselves’. The central importance and powerful effects of positive teacher–student relationships have been explained through various theoretical frameworks including attachment theory and self-determination theory (see Wentzel Reference Wentzel, Wentzel and Wigfield2009). However, research examining teacher–learner relationships or rapport remains sparse in general education and virtually non-existent in language education (for some exceptions, see Senior Reference Senior2006; Nguyen Reference Nguyen2007; Farrell Reference Farrell2015; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zhou, Barber and den Brok2015; Gkonou & Mercer Reference Gkonou and Mercer2017). Yet, from a systems perspective, I must agree with Wilcken & Roseth (Reference Wilcken, Roseth, Rubie-Davies, Stephens and Watson2015: 177) that ‘a full account of academic achievement or success in school must include the quality of the teacher-student relationship’. This means that, at present, the field of PLL, indeed SLA in its entirety, has a notable gap. In network relational terms, we do not understand both nodes in this key relationship (learner and teacher), nor do we properly understand what constitutes a quality teacher–learner relationship in a language education setting, nor how it develops, is maintained or relates to other key learning outcomes or variables.

Fundamentally, the interaction of all the relationships in the classroom together generates emergent collective qualities such as group dynamics, rapport, trust and classroom atmosphere – all of which are known to be vitally important for effective teaching and ultimately successful learning (Bryk & Schneider Reference Bryk and Schneider2002; Dörnyei & Murphey Reference Dörnyei and Murphey2003; Babad Reference Babad2009; Roffey Reference Roffey2011). From a network perspective, we can imagine that the hub of all relationships in the classroom is the teacher. The teacher forms a relationship with each individual learner as well as the group collective as a whole. As part of the system, every person in the class both defines the group and is in turn defined by it. While all participants can influence group dynamics and collective states, in network relational terms, the teacher is likely to be the most interconnected member of the group, and, as such, they are presumably the most influential node in the network. It means a teacher's psychology and professional wellbeing is in a position to be highly ‘contagious’ for the psychology of the whole group as a collective and for individuals within the social network of the classroom.

5.2 Zooming in on the teacher as an individual

I now want to ‘zoom in’ (Davis & Sumara Reference Davis and Sumara2006) within the nested system view and focus on the teacher per se and consider how a relational perspective can help us to appreciate the embodied and situated psychologies of teachers themselves as a key node in the classroom collective.

The system we are focusing on here is defined as a teacher's embodied psychology. Again, the system is open and boundaries are permeable. As already outlined, interesting questions are being raised as to what extent an individual's psychology can be understood in any sense as a bounded system separate from other people and the environment. In SLA, socio-cognitive work centres on the premise that ‘mind, body and world function integratively’ (Atkinson Reference Atkinson and Atkinson2011: 143; Batstone Reference Batstone2010). As an approach, it challenges the dichotomy and distinction between mind and world, and argues that we cannot be detached on either a mental or physical level from our contexts. One dimension that is becoming widely accepted as being inseparable is the body-mind dualism, which has persisted throughout psychology's history. Increasingly, neuroscience and cognitive science are discussing embodied cognition, although I prefer the term embodied psychology to retain the holism of human psychology. From a complexity perspective, the body and mind can be seen as one system. Claxton (Reference Claxton2015: 3) explains, ‘we do not have bodies; we are bodies’. While disagreements about various claims related to embodied cognition persist (see, e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson2002), for our purposes here, I will accept that the body and mind are highly interconnected, with the body providing information on our experiences with the world (often in the form of unconscious emotions and intuitive knowledge), chemically affecting our cognitions (see, e.g., effects of lower insulin levels on willpower – Baumeister & Tierney Reference Baumeister and Tierney2011) as well as serving as an extension of our cognitive processes (such as through gesture and body language).

There are two key reasons why I am especially keen to maintain an embodied view of psychology for educators. First, this perspective highlights the importance of physical wellbeing for our psychological wellbeing and our ability to think and function effectively (Biddle, Fox & Boutcher Reference Biddle, Fox and Boutcher2000; Mutrie Reference Mutrie2002; Edwards Reference Edwards2006; Biddle & Mutrie Reference Biddle and Mutrie2008; Ratey & Hagerman Reference Ratey and Hagerman2009). Given concerns about burnout and teacher stress, this embodied perspective is important to help educators appreciate the need to look after themselves physically in order to be effective cognitively and creatively as educators (see Holmes Reference Holmes2005; Castle & Buckler Reference Castle and Buckler2009). The second point concerns my belief in the important role played by intuitive knowledge for educators (Atkinson & Claxton Reference Atkinson and Claxton2000; Tsui Reference Tsui2003; Gkonou & Mercer Reference Gkonou and Mercer2017), despite the lack of attention this has generally received from researchers and teacher educators. Although, as one anonymous reviewer noted, various forms of practitioner research are increasingly examining and exploring teachers’ intuitive classroom knowledge. While the mechanisms of how intuitive knowledge functions remain unclear, it seems likely that bodily responses, emotions and unconscious cognitions contribute at least in part.

From a relational perspective, psychology is also seen as integrated with the world through one's own personal meaning-making. As outlined earlier, I take the view that contexts are within us (Mercer Reference Mercer and King2016). We are not situated within externally defined, objective, monolithic contexts. Rather, we relate to them in our own personal ways based on our personal frames of reference. ‘An environment may exist, but it is our definition of it that is important’ (Charon Reference Charon2009: 28). This line of thinking forms the basis of my work on the self, in which I have moved towards a relational position. I define the self not as having relationships but as being relationships (see Mercer Reference Mercer, Gregersen and MacIntyre2017; cf. Donati & Archer Reference Donati and Archer2015). Our sense of self emerges from our relationships to the social and non-social world around us. These relationships can be formed in relation to more concrete objects such as the class, peers, teachers, literature, films, materials and specific contexts but they can also be formed in relation to concepts, ideas, past experiences as well as future goals. Essentially, this relational perspective is a holistic view of psychology which sees our sense of self as constantly emerging from the interaction of a network of personally relevant relationships. Relationships can be thought of as ‘conglomerates’ (Dörnyei Reference Dörnyei, Ellis and Larsen-Freeman2009), which encompass what we think, feel and do in relation to various aspects of our lives. These relationships are inherently situated. Employing our agency to differing degrees of consciousness, we relate to our present contexts and cultures based on our frames of reference, which also include our subjective interpretations of our past experiences of cultures and contexts. These contexts are inherently embedded within the processes of how we relate, although it is worth reiterating that we can also construct explicit relationships to specific contexts and artefacts, too.

For teacher psychology, it means we need to understand how teachers relate to their worlds. Setting boundaries on the professional domain is problematic and research must reflect teachers’ own perceptions of domain boundaries. Definitions of domains are highly personal and what is relevant for a person's professional domain will vary in ways meaningful for an individual at any one point in time (Mercer Reference Mercer, Gregersen and MacIntyre2017; Saleem in press), but it is likely that personal and professional spheres will interconnect strongly for teachers (Day et al. Reference Day, Sammons, Stobart, Kington and Gu2007; Day & Gu Reference Day and Gu2010). Indeed, it is questionable whether these domains can ever be meaningfully thought of as distinct. From what we know in respect to teacher psychology, we can expect that a teacher's relationships with their learners will be key (Hargreaves Reference Hargreaves2000; Kyriacou Reference Kyriacou2001; Split, Koomen & Thijs Reference Spilt, Koomen and Thijs2011), as will their relationship to their schools, resources, tasks, colleagues and head teachers (Day et al. Reference Day, Sammons, Stobart, Kington and Gu2007; Chang Reference Chang2009; Rogers Reference Rogers2012). However, it will also be important to understand how they relate to their own competences in different areas of their professional lives, their beliefs about teaching and learning as well as their personal biographies (past) and personal goals (future) for purposes of their professional development (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy Reference Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy2007; Skaalvik & Skaalvik Reference Skaalvik and Skaalvik2010; Bobbit Nolen, Ward & Horn Reference Bobbit Nolen, Ward, Horn, Richardson, Karabenick and Watt2014; Cabaroglu Reference Cabaroglu2014; Kalaja et al. Reference Kalaja, Barcelos, Aro and Ruohotie-Lyhty2016; Wyatt in press).

Essentially, a relational view offers a potentially useful lens for understanding teacher psychology. It is one which seeks to retain a more holistic view of the individual's psychology linking various cognitive, affective and motivational dimensions; it attempts to connect mind, body as well as social contexts; it incorporates the ongoing temporality of human experience in which we narrate our lives across our pasts, presents and futures (Irie & Ryan Reference Irie, Ryan, Mercer and Williams2014); it is inherently dynamic as we relate actively with the possibility to change how we relate and form new relationships; and it reflects human agency in showing how we can, to varying degrees, actively construct relationships and thereby potentially alter how we choose to relate to various aspects of our lives. Conceptually, I have also found it very accessible and easy for teachers and learners to engage with, and it is a useful way of making our complex psychologies more readily comprehensible for those who wish to work with a consideration of psychology in mind (Mercer Reference Mercer, Gregersen and MacIntyre2017).

6. Conclusion

Teachers matter. They matter to the wellbeing and achievement of their learners ‘not just because of what and how they teach, but, because of who they are as people’ (Day et al. Reference Day, Sammons, Stobart, Kington and Gu2007: 1). Their psychology is defining, both for themselves and their professional wellbeing but also for the quality of their teaching, their learners' learning and the psychological experiences of their learners. In this talk, I have argued that teacher psychology needs to be added more prominently to the PLL research agenda as a matter of urgency. We have seen how the field is heavily imbalanced in its coverage and spread of research regarding learner and teacher psychology. I have argued that teachers are one of, if not the, most valuable stakeholders in language learning and teaching processes. To have comparatively so little understanding of what makes teachers tick and flourish in their professional roles is lamentable.

In addition, I have outlined what I believe to be characteristics of a relational perspective, which I suggest could offer a useful lens to complement other approaches to researching teacher or learner psychology. I have shown how teacher psychology is vitally important as it constitutes one key node in the classroom social network of relationships and is intricately linked with learner psychology. I feel that relational thinking can open up holistic perspectives on psychology generally, drawing attention to the various, complex ways we relate to the world and others around us as well as to the character of collective psychologies and interconnected interpersonal psychologies. While there remain many empirical challenges for complexity, relational and collective perspectives on psychology, these must be viewed as opportunities to extend our thinking and grow beyond the boundaries of our current researching habits, modes, and units of analysis. The field of PLL finds itself in an exciting period of growth and exploration. As part of this expansion, it is high time we put teacher psychology centre stage on the research agenda for the coming years and, hopefully, at PLL3, we will see the critical importance of teacher psychology also reflected in the empirical profile and professional discourse of the conference and field as a whole.

Sarah Mercer is Professor of Foreign Language Teaching at the University of Graz, Austria, where she is Head of ELT methodology and Deputy Head of the Centre for Teaching and Learning in Arts and Humanities. Her research interests include all aspects of the psychology surrounding the foreign language learning experience. She is the author, co-author and co-editor of several books in this area.