Introduction

‘Joe won't inject you with bleach’ reads text superimposed over a photo of Joe Biden, posted by the Instagram account of Settle for Biden, a social media campaign targeting Progressive Democrats, in April 2020 (Settle for Biden 2020a). Advocating that US citizens vote for Biden in the 2020 presidential election, the sentence calls attention to the over-the-top dangerous behaviors of President Donald Trump in the chaotic and fearful beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier that month, President Trump had spun fantasy cures for COVID that included the possibility that Americans could consume and inject bleach to fight the virus (Chiu, Shepherd, Shammas, & Itkowitz Reference Chiu, Shepherd, Shammas and Itkowitz2020) without providing scientific information in support of the fatal suggestion. The highly successful Settle for Biden campaign offered voters an alternative to Trump: a president who is ‘normal’ and will not propose these kinds of absurd and dangerous solutions. A stream of campaign posts like this one construct Biden as having a kind of normalcy voters can ‘settle for’, even if this normalcy is not particularly desirable. Analysts of language and politics have pointed out that US presidential politicians often counter their positioning as extraordinary by using a ‘middling style’ to portray themselves as one of the people (Hill Reference Hill1999:683, citing Cmiel Reference Cmiel1990). Yet the phrase ‘Joe won't inject you with bleach’ is hardly a middling style, instead creating a novel form of commonsense mediocrity that is so obvious it comes across as humorous. Herein lies the question this article seeks to answer: How does a political social media campaign in an era of heightened celebrity politics produce its candidate as merely ordinary?

Political discourse in the US has shifted dramatically over the past decade, as Donald Trump became a president in 2016 well known for a hyperbolic communication style characterized by diverse commentators as a spectacle unprecedented in American politics (Hall, Goldstein, & Ingram Reference Hall, Goldstein and Ingram2016). As a result of Trump's communication style and associated policies, many in the US have come to view politics, and American society more generally, as especially chaotic and tumultuous. Overall, US political campaigns typically use communicative strategies to frame the candidate they support in a positive light while framing opposing candidates in a negative light (Duranti Reference Duranti2006; Sclafani Reference Sclafani2015; Arnold-Murray Reference Arnold-Murray2021). These communicative strategies are seen in the ways that the official presidential campaigns of Donald Trump and Joe Biden each represented their candidate as an outstanding individual who has risen above the rest, well-positioned to govern the country and participate in foreign affairs.

In sharp contrast, the Settle for Biden campaign suggests that Joe Biden's ‘mediocrity’ made him the best choice for president. In the face of four more years of a president considered by Liberals and Progressives to be a dangerous and immoral figure, the campaign constructed Biden as the obvious choice because, in contrast to Trump, his level-headedness had the potential to bring the country back to safety and sanity. At the time the campaign was launched, many on the Left expressed hesitancy about voting for Biden, finding him unideal because he ran as a more moderate candidate (Khalid Reference Khalid2019). The Settle for Biden campaign capitalized on these interconnected sociopolitical phenomena by advocating that individuals should vote for Biden not because of his policy positions, but rather because he is, in a word, normal. The campaign thus exploits what linguistic anthropologists would describe as the ‘unmarked’ power of normativity (Barrett Reference Barrett, Zimman, Davis and Raclaw2014; Alim, Reyes, & Kroskrity Reference Alim, Reyes, Kroskrity, Samy Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020; Hall Reference Hall2021) to highlight the abnormality of the opposing candidate.

While the upscaling language and communication style of Trump has been a popular site of exploration for linguists (e.g. Hall et al. Reference Hall, Goldstein and Ingram2016; Sclafani Reference Sclafani2018; Hodges Reference Hodges2020; McIntosh & Mendoza-Denton Reference McIntosh and Mendoza-Denton2020; Stange Reference Stange, Schneider and Eitelmann2020), I focus, in contrast, on the downscaling language of the Instagram campaign in its often humorous posts depicting Biden as a boring, normal candidate who is ‘good enough’ to be president and who counters the abnormal danger posed by his competitor. Launched shortly after Biden became the presumptive Democratic nominee, the campaign published about 255 unique posts on Instagram and gained over 200,000 followers before the November 3rd election. The posts tend not to contain substantive information about Biden's policies or stances but rather rely on short humorous statements that construct scalar relationships between Biden and Trump to make their arguments.

Specifically, the campaign frames voting as a consumer choice and thus one of personal taste and sensibilities—a choice that only loosely connects to the candidates’ values or policies and more strongly connects to audience perceptions of what kinds of things are desirable, normal, and negative. Whereas some political campaigns have marketed their candidates as the desirable kind of ‘average Joe’ one might want to grab a beer with (as with many of the campaigns of Democrats running for office in 2020, including Biden; see Cohn Reference Cohn2019), the Settle for Biden campaign instead markets Biden as a kind of mediocre consumer good—as a non-extreme middle ground that is a safe bet. The campaign's focus on ‘settling’ for a mediocre candidate was feasible only in the sociopolitical context of 2020, at a time when Trump's leadership had come to be perceived as chaotic and dangerous. This sentiment is poignantly exemplified by a comment responding to a Settle for Biden post published on August 10: ‘remember prior to 2016 when politics was just like ‘“dad's taking out the trash” and not “dad's going to get drunk and kill everyone?”’.

In my analysis of the campaign, I adopt a scalar perspective of normativity, viewing normativity as interactionally produced through appeals to scales constructed by centers of authority. Scalar frameworks have received growing attention in sociolinguistic and linguistic anthropological research investigating normativity (e.g. Blommaert Reference Blommaert2007a; Carr & Lempert Reference Carr, Lempert, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016; Hall, Levon, & Milani Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019). For instance, Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2007a) proposes that the analysis of scales must attend to the production of norms at both macro and micro levels: scales are anchored by specific centers of authority (e.g. institutions such as the family, the media, the nation-state, and religion) that license and create norms and expectations for specific practices, beliefs, and ways of being. In this ‘polycentric’ view of interaction, individuals orient to multiple centers, implementing the norms licensed by each center as they communicate with others. Seen within these terms, Settle for Biden produces scalar language located in divergent centers to portray what is normative, positioning Biden as mediocre or average compared to an idealized candidate. A clear example of this is the campaign's invocation of an educational center of authority to situate Biden as a ‘C+’ compared to an ideal candidate who is an ‘A’.

Moreover, while making salient the normal nature of Biden, the campaign uses semiotic strategies that appeal to interconnected normativities associated with class, age, race, and gender to create unmarked centers of authority by which Biden and Trump can be compared. To draw on Hall (Reference Hall2021:303), the campaign produces ‘language in the middle’ within each of these discursive frames, constructing Biden as neither extraordinary nor reprehensible, yet to which the campaign and its audience are positioned as superior. Crucially, the campaign constructs multiple dynamic scales that operate simultaneously and intersect with one another. For instance, a scale exploiting the semiotics of class relations may be used to construct a judgement scale regarding the potential impact of Biden's environmental policies.

In the next section, I ground my analysis of the Settle for Biden campaign in previous literature related to the scalar production of normativity. I then introduce the data I examine and the methods I employ by explicating a prominent campaign image that celebrates Biden's ‘foul ball’ as ‘better than a strike’. Next, I provide a more comprehensive analysis of the ways in which the campaign multimodally produces Biden as a normative candidate that voters should ‘settle for’ in the face of Trump's abnormality, focusing on the scalar production of norms related to class and age. Finally, the conclusion summarizes my findings about how the Settle for Biden campaign constructs interconnected normativities to portray Biden as normal, questioning the future of this strategy in an evolving political climate that continues to be identified as chaotic.

Scalar normativity

This article draws from perspectives developed within sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology to explore how Settle for Biden produces and exploits Biden's normativity. I view normativity as inherently scalar, as norms emerge from hierarchically subjective relationalities. Humans construct scales to make sense of the social and spatial-temporal worlds they occupy. As Carr & Lempert (Reference Carr, Lempert, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016:11) argue, ‘social actors not only construct and feel their worlds in scalar terms but also conduct themselves—and try to affect others—accordingly’. Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2007a:16) suggests scale as a concept that offers ‘a vertical, power-saturated spatial metaphor for sociolinguistic phenomena and practices’. In particular, he proposes that relations between scales are governed by orders of indexicality which compete against one another and are valued differently based on systems of authority, control, and evaluation (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2007b). Intertwined with this is his conceptualization of polycentricity: although many interactions may appear ‘‘stable’ and monocentric’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2007b:120), there always exist multiple norms that may be oriented to in any given interaction. These norms and the evaluation of them, emergent from centers of authority, are associated with and license clusters of semiotic features that can be viewed as indexical. A center may be an institution such as religion, a legal system, a nation-state, a peer-group, and so on. As we see in the analysis that follows, the Settle for Biden campaign exploits a number of different scalar centers when advocating for the importance of ‘settling’ for its candidate.

Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2007a:5) additionally argues that through the construction of scales, ‘people make physical space and time into controlled, regimented objects and instruments, and they do so through semiotic practices’. These semiotic constructs of specific timespaces populated by certain social types are known as chronotopes (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1981; Agha Reference Agha2007). Chronotopes can support systems of normativity when they are used to construct certain behaviors as normal and desirable and others as deviant and undesirable (Blommaert & De Fina Reference Blommaert, De Fina, Fina, Ikizoglu and Wagner2017; Sanei Reference Sanei2022). They become scalar when they evoke social relations and value systems that are set into competition with the social relations and value systems evoked by other chronotopes. For instance, as demonstrated by several of the examples discussed in this article, a chronotope of a mid-twentieth-century traditional US may be discursively brought into competition with a modern Progressive US timespace.

A scalar perspective at its core requires a consideration of processes of division and exclusion. Queer theorists Wiegman & Wilson (Reference Wiegman and Wilson2015:16) argue that norms are relationally constructed as they are ‘dispersed calculation[s]’ of an average established by relationships between and within groups. In this sense, scales are also ideologically motivated (Carr & Lempert Reference Carr, Lempert, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016); Hall and colleagues (2019:483) argue that ‘establishing norms is always an ideological process… through which markers of social difference are created, iconized, and imbued with moral and affective weight’. Normativities, and thus the construction and ordering of scales, are continuously changing both at micro levels of interaction and macro categories of institutions (Wiegman & Wilson Reference Wiegman and Wilson2015). The behaviors of persons who defy the norms that maintain the status quo are marked, while characteristics associated with powerful identities go unmarked and are rendered invisible (Hill Reference Hill1999). This point is central to Hall's (Reference Hall2021:3) analysis of how middle classness in India is produced against what it is not, specifically through the use of ‘language in the middle’ that is projected as neither elite nor working class. Hall argues that the macro category of middle class is constructed though this scalar social distinction, rather than purely economic circumstances. The Settle for Biden campaign similarly appeals to unmarked normativities across macro categories when producing humorous scales that position Biden as a candidate ‘in the middle’.

Importantly, normativities are at all times interconnected and cannot be studied in isolation (Reyes Reference Reyes2017; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019; Hall Reference Hall2021; Khoo Reference Khoo2023). This means that scalar relations simultaneously govern normativities such as those related to class, race, gender, and sexuality. In the US, normativities surrounding middle classness, whiteness, masculinity, and heterosexuality tend to go unnoticed due to the hegemonic power held by those at the top constructing the scales. Those in power hold unmarked qualities because they adhere to and maintain the norms that they themselves create. By defining the normative by what it is not, the dominant classes establish a schema of commonsense negatives that are difficult to challenge. Commonsense ideas of what it means to be ‘normal’ are likewise exploited by Settle for Biden in its production of scalar judgements that seem objective, but actually rely on privileged middle-class value systems.

Data and methods

This article involves a qualitative multimodal analysis of six Instagram posts, drawn from a much broader corpus of 255 posts, published by the Settle for Biden campaign during the 2020 election. The campaign itself was comprised of a diverse group of Progressive organizers in the US under the age of twenty-five. Many of the organizers previously worked on campaigns for Progressive candidates and causes and came together separately from the Democratic Party to campaign for Joe Biden. Progressivism, as understood by the youth who engaged with Settle for Biden, is a political orientation Left of the Democratic Party which supports social policies championing civil rights and economic policies advancing wealth redistribution. Sam Weinberg, the campaign's nineteen-year-old founder, stated that he established Settle for Biden because he saw disillusioned young voters casting Biden and Trump as ‘two sides of the same coin’, while he believed Biden was a far better choice for Progressives both personally and politically (Morin Reference Morin2020). The target audience of the Settle for Biden campaign were young Progressive social media users who did not support Biden as ‘their’ candidate. Many of the people engaging with the Instagram posts had voted for Progressive candidates in the Democratic Party presidential primary elections—namely, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Senator Bernie Sanders—and expressed hesitancy about Biden's moderate policy positions.

My analysis considers how the selected six posts are situated within the overall themes and trajectory of the 2020 social media campaign. The examined Instagram posts were published throughout the campaign from its beginning in the spring of 2020 to the fall of 2020. I selected these particular posts for analysis because they are characteristic of many published by the campaign: they promote Biden's normalcy (and normativity in general) as an easily recognizable type of normal, yet one that is not desirable to its audience unless compared to the abnormality of Trump. Each of these posts consists of an image (usually a photo of Biden) overlaid with a short phrase of embedded text and an accompanying text caption.

I perform a multimodal digital discourse analysis of the data, examining the ways in which the images, embedded text, and text captions of each Instagram post come together to form larger meanings and representations of Biden, Trump, normativity, and danger. In addition to linguistic anthropological literature on scales, chronotopes, and normativity, I draw on Wortham & Reyes's work on (2021) on digital discourse as multimodal sign use and Kress & van Leeuwen's (Reference Kress and van Leeuwen1996, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2001) framework of social semiotics conceptualizing meaning-making as a multimodal activity in which similar meanings can be conveyed across different semiotic modes, including verbal and written language, visual image, gesture, and so on. Communication on Instagram, like on other popular social networking platforms, is inherently multimodal, as users commonly publish photos and videos accompanied by text captions as well as hashtags, emojis, and more. As diverse scholars of digital media have noted, social media interactions construct and mediate social norms at different scalar levels (e.g. Sanei Reference Sanei2022), such as those related to class, age, race, and gender.

Alongside my attention to multimodality, I employ Bakhtin's (Reference Bakhtin1986) framework of intertextuality as I consider each Settle for Biden Instagram post as a text situated within current and past discourses and events in the United States. Intertextuality refers to the relationship between different kinds of semiotic texts—past, present, and future—or in the words of Fairclough (Reference Fairclough1992:270, citing Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1986), ‘the ways in which texts are shaped by prior texts that they are “responding” to and by subsequent texts that they “anticipate”’ (see also Gordon Reference Gordon2023). My approach is thus consistent with Wortham & Reyes's (Reference Wortham and Reyes2021:167) advocacy for ‘discourse analysis beyond the speech event’, as I trace the ‘emerging intersections’ that give rise to social meaning and the allure of this advertising campaign. I draw from events and news stories in the US on or close to the dates that the posts were published to analyze how the posts are situated within current and past speech events in the US. In creating a dynamic campaign that regularly engages posts with external discourses sharing similar meanings, Settle for Biden creates intertextual linkages between past, present, and future messaging.

My analysis of the example below (Figure 1) illustrates how I approach the data analyzed in this article. Posted by Settle for Biden on September 15, 2020, the image and associated text draws an indirect comparison between Biden and Trump by positioning both candidates on a scale highlighting the success of bat swings in baseball.

Figure 1. Because a foul ball is better than a strike (Settle for Biden 2020b, published September 15).

The photo of the post shows Biden wearing a suit and holding a white baseball bat, posed as if he is about to swing at a baseball. Displaying a cheerful look and surrounded by a white highlight, Biden is the focal point of the image and is superimposed on a faded photo of a baseball park. The text embedded in the image states, ‘Because a foul ball is better than a strike’, likening Biden to a foul ball hit in baseball. This produces Biden fairly low on the scale of success of bat swings in baseball, but at least it's ‘better than a strike’, a bat swing indexical of Biden's competitor Donald Trump.

Figure 2 below displays how the image and its embedded text map Biden and Trump onto this metaphorical evaluative scale. While Biden is scaled above Trump, there is also an unnamed ideal candidate for Progressives placed at the top: home run. The notion of an ‘ideal candidate’ is essential to the construction of scalar relations and normativities by the campaign, as many Progressives considered voting for third-party candidates over Biden in the general election due to ideological disagreements, even though they did not stand a chance of winning; some Progressives also considered not voting at all. In constructing the election as a binary choice between only two potential winners on this scale, the campaign advertises ‘mediocre’ Biden as the best choice for president, even if he is not one's first choice.

Figure 2. Baseball bat swings scale.

While the text embedded in the image likens Biden to a ‘foul ball’, the caption accompanying the image likens him to ‘a swing-and-a-miss’ (a strike) that is preferable to ‘getting hit in the face with a fastball’. In this alternative scale (Figure 3), the details of the scale shift, but the positionality of Biden as superior to his opponent but still average remains: Biden is the ‘safe’ option in comparison to a dangerous and unpredictable competitor.

Figure 3. Baseball actions scale.

As baseball is an iconic American sport, Settle for Biden's depiction of its candidate as a baseball player indexes his normative American qualities and values, appealing to sport as a center of authority. While baseball remains a quintessential US sport, it declined in popularity with the advent of television in the 1960s and now trails far behind American football in popularity, particularly among those under 30 (Enten Reference Enten2022). For many youth engaging with social media, baseball is now more representative of an idealized American past time than a current American pastime. Accordingly, the campaign post situates an aging Biden in the chronotope of a previous America, scaling the ‘normal’ timespace of an American past (‘foul ball’) against both the idealized timespace of its contemporary social media viewers (‘home run’) and the unpredictable timespace of a Trumpian future (‘strike’).

Further, the white highlight around Biden's body in the Instagram image visually depicts him as angelic, much in the same way that mainstream US Christian imagery depicts deities and angels as surrounded by white light. The image of Biden as angelic thus recalls normative (white) Western Christian beliefs and imagery. Yet this is also an ironic commentary that makes fun of the expectation that campaigns should portray their candidates as exceptional. It brings the audience into the joke that Biden, in contrast to this angelic representation, is actually just an ‘average Joe’—though an ‘average Joe’ that is nevertheless preferable to his competitor.

This Instagram post is rich with complex intertextual references. First, the depiction of Biden as an angelic baseball player is an intertextual tie to the popular 1994 American movie Angels in the Outfield (Smith, Roth, Birnbaum, & Dear Reference Smith, Roth, Birnbaum and Dear1994), in which a boy prays for the Los Angeles Angels baseball team to win the championship leading to the World Series. In the film, angels begin to appear in the outfield and assist players in making extraordinary catches to help the team win. Crucially, the movie's famous line is ‘Ya gotta believe’, espousing a philosophy that the campaign also offers its audience: while Biden is not someone you support, ‘ya gotta believe’ that he is the better candidate. Second, it is also significant that this post was published on September 15, a date associated with the 1860 publication of a famous political cartoon featuring Abraham Lincoln (Maurer Reference Maurer1860), regularly included in US high-school history textbooks (e.g. Bailey, Kennedy, & Cohen Reference Bailey, Kennedy; and Cohen2012:410). In the satire (Figure 4), Lincoln is shown holding a baseball bat alongside his three presidential opponents. The main text of the cartoon reads: ‘THE NATIONAL GAME. THREE ‘OUTS’ AND ONE ‘RUN’. ABRAHAM WINNING THE BALL.’ In sharp contrast to Biden in the Settle for Biden image, Lincoln is represented in this earlier image as an exceptional baseball player.

Figure 4. 1860 Lincoln satire ‘The national game. Three “outs” and one “run”’ (Maurer Reference Maurer1860).

This sports metaphor produces Lincoln as a strong candidate who is the obvious choice and likely winner of the 1860 presidential election. Biden, in contrast, is represented through the same metaphor as a below-average player, not one who is exceptional in any way; however, Trump is portrayed as giving the worst performance possible. Many readers in Settle for Biden's target audience will not be familiar with this pro-Lincoln 1860 satire, but some may make the connection between the two. The intertextual linkage of Biden to Lincoln, even if not congruent, scales Trump as a president who is as far from Lincoln as possible. As Trump repeatedly compared himself to Lincoln throughout his presidency (Blumenthal Reference Blumenthal2019), the Settle for Biden image serves as a humorous challenge to these discourses, indirectly painting Trump as absurd in historical as well as contemporary context.

In the next section, I employ this analytical approach in my examination of five other posts published throughout the Settle for Biden Reference Biden2020 campaign. The images and texts of these posts construct interrelated meanings across semiotic modes by respectively drawing from normative US understandings of class and age.

Norming Biden on Instagram

The analysis below explores how Settle for Biden constructs scalar relations between Biden and Trump by representing Biden as normative through multiple interconnected and simultaneous scales in each Instagram post. The campaign employs American icons, multimodal metaphors, and evaluation of language use to exploit Biden's normativity in his favor. I structure my analysis by first discussing the ways that the campaign ‘norms’ Biden by appealing to normative ideals associated with class and then age. Following Hall & colleagues’ (Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019:484) call for an intersectional approach to ‘normativity in (inter)action’, I view norming as an action that constructs its object as normative.

Norming Biden through class

The Settle for Biden campaign commonly portrays Biden as representative of the US middle class. In this section, I discuss three examples that rely on the audience to have a particular sort of middle-class sensibility to agree with judgements that inform the comparisons made between Biden and Trump. In the first example (Figure 5), Biden is compared to a Dairy Queen ice cream cone, metaphorically represented as undesirable but safe to consume. In the second example (Figure 7), a prescriptive judgement of Biden's pronunciation of ‘Yosemite’ is used to make a larger positive statement about his environmental policies in contrast to those of Trump. The third example (Figure 8) places Biden in a school setting and constructs an academic grade scale to position Biden as average yet superior to Trump, appealing to education as a center of authority. Although these three examples achieve their effects by each indexing a different set of nodes on a scale of class relations, they succeed in situating the consumer of the image as superior to Biden while also indirectly situating Biden as superior to Trump. By portraying Biden as normative within the chronotope of a mid-twentieth-century middle-class America (that is, as ‘mediocre’), the posts interpellate a discerning middle-class reader who finds humor in these class-based judgements.

Figure 5. Unappetizing but still edible (Settle for Biden 2020c, published April 30).

A more careful reading of the three examples reveals their scalar implications. The image in the first example shows the hand of an older white person holding an ice cream cone with the Dairy Queen ‘DQ’ label recognizable. Biden's affinity for ice cream is commonly known, and one that Settle for Biden repeatedly referenced. In the image, Settle for Biden draws a comparison between Biden and the ice cream that is being offered to readers of the post: Biden is the thing being offered (the ‘unappetizing’ ice cream), but he is also the offeree, as the hand holding the ice cream cone in the image appears to be his. The visual and verbal elements of the post thus come together to position Biden as reflexively offering himself to his audience as a candidate for president.

While Settle for Biden could have depicted any kind of ice cream in the photo, the choice of Dairy Queen, with the label facing the camera, relates Biden to someone with a mainstream taste for American fast food. Dairy Queen's link to traditional small-town life, especially during the 1950s and 1960s in the Midwest and South, is commonly thematized in popular media (e.g. Greene Reference Greene2001; McMurtry Reference McMurtry2001). While Dairy Queen products are still consumed across the US, this indexicality constructs an older, non-urban, middle-class American timespace of which Biden is representative. The campaign's repeated linkage of Biden with chronotopes of an older, traditional, and also white America acknowledges the Progressive vision of Biden as out of touch with younger cosmopolitan voters and people of color, while also situating him as more appetizing than his competitor.

Although Dairy Queen is one of the largest chains of ice cream stores in the US, the ice cream itself varies in popularity. Dairy Queen's soft serve tends to cost less than other kinds of ice cream, and it is thus more indexical of a lower-class positionality than, say, the comparatively gourmet chains Häagen-Dazs, Cold Stone, and Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream. The representation of Dairy Queen soft serve as ‘unappetizing’ is therefore a judgement that is more likely to resonate with those whose habitus orients to more expensive ice cream or who perhaps refrain from frequenting fast-food restaurants. In other words, the positioning of Dairy Queen as unappetizing and Biden correspondingly as mediocre is achieved by appealing to class-based gustatory norms. Voting for Biden is framed as a consumer choice akin to choosing what ice cream to eat: like Dairy Queen soft serve, Biden is a choice of comfortable mediocrity. As with the swing-and-a-miss versus getting-hit-in-the-face-with-a-fastball comparison seen in Figure 3, the scale of judgement constructed in this post positions Biden as unideal yet safe and Trump as inedible and thus unsafe for consumption. Figure 6 displays this scalar production of normativity based on gustatory judgement, which gains its meaning from the scalar class relations that underlie it.

Figure 6. Gustatory judgement scale.

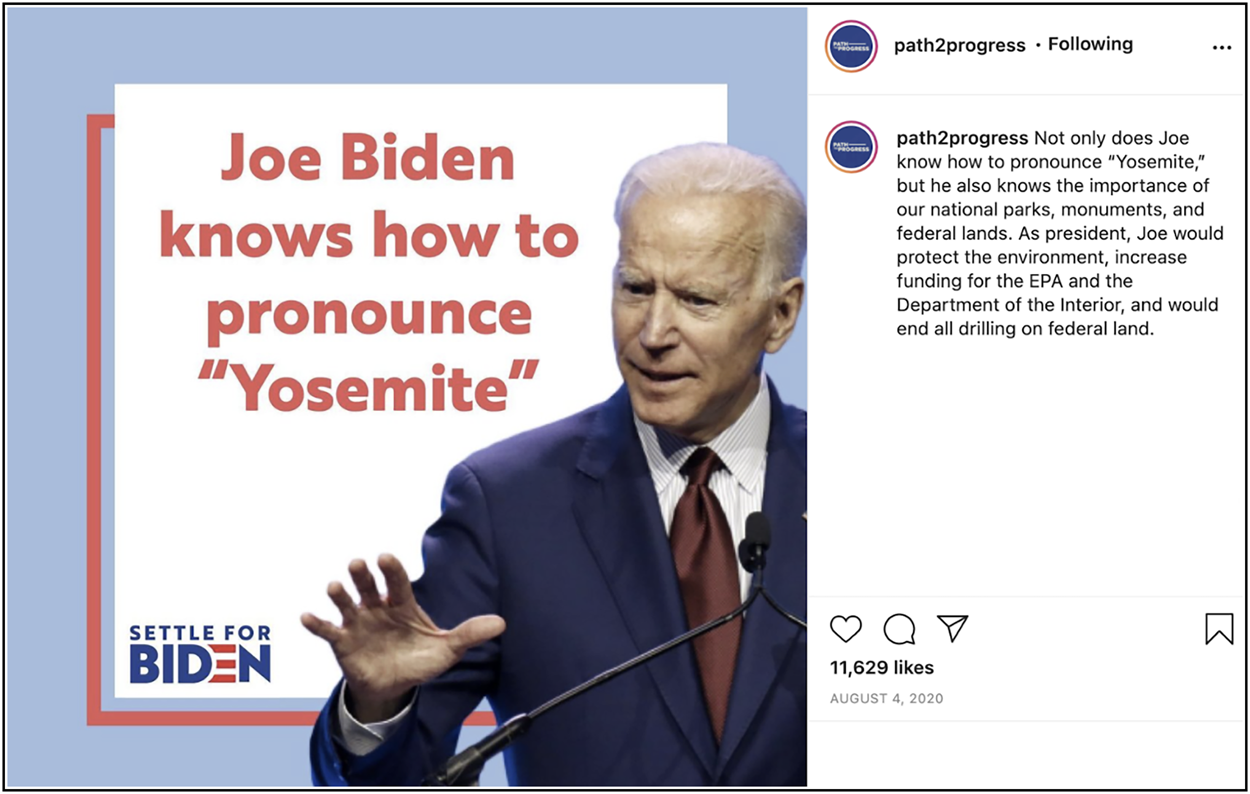

In the next example, the campaign employs prescriptive judgements of language use to situate Biden as normal and therefore better than Trump (Figure 7). Claiming ‘Joe Biden knows how to pronounce “Yosemite”’, this post was published on the same day that President Trump mispronounced the name of the National Park as [yosɛma͡ɪt] rather than the prescriptive pronunciation /yosɛmɪɾi/. Settle for Biden does not explicitly mention Trump nor his mispronunciation of the word, but rather offers Joe Biden's knowledge of pronunciation as an example of a kind of baseline normative knowledge that everyone should have.

Figure 7. Joe Biden knows how to pronounce ‘Yosemite’ (Settle for Biden 2020d, published August 4).

The caption of the post contains more substantive information about Biden's policy positions than most of the other Instagram posts associated with the campaign: ‘Not only does Joe know how to pronounce “Yosemite”, but he also knows the importance of our national parks, monuments, and federal land. As president, Joe would protect the environment, increase funding for the EPA and the Department of the Interior, and would end all drilling on federal land.’ By contrasting Biden's ‘correct’ pronunciation with Trump's mispronunciation, the post contrasts not only their intelligence, but also their educational awareness of US national parks and dedication to protecting the environment.

For this post to come across as humorous, the campaign relies on its Instagram audience to have awareness that Trump recently mispronounced ‘Yosemite’. While judgement of Trump's language falls within the tradition of criticizing and mocking American presidents’ pronunciations (e.g. George W. Bush's pronunciation of ‘nuclear’; see Sheidlower Reference Sheidlower2002), Settle for Biden criticizes Trump's pronunciation to make a larger negative claim about his environmental policies in comparison to Biden's. While the prescriptive pronunciation of ‘Yosemite’ is derived from Southern Miwok, its widespread ‘correct’ use can be linked to (white) middle-class norms regarding not just language use but also knowledge of US national parks. ‘Yosemite’ is a word not pronounced as it is spelled; this may cause those without experience learning about or visiting the park to pronounce it more closely to how it is spelled (as Trump did). For some, the experience of Yosemite, whether situated in the domain of education or of leisure, may be out of reach.

In other words, the campaign situates knowledge of the ‘correct’ pronunciation as normative (with Biden as correspondingly normative and Trump as correspondingly non-normative) by orienting to a certain faction of the US middle class as a center of authority. As numerous sociolinguists have argued, prescriptive grammar serves to keep those with experiential access to Standard American English in power. Alternatively, mocking the use of non-standard linguistic forms maintains hegemonic racial and class power (Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green2012). This kind of language policing is thus a distinctively white middle-class activity, with Trump and Biden situated at divergent positions on the class scale.

In addition, the invocation of a US national park takes its audience to an imagined pure and better America. National parks are a type of US entertainment that is ideologically pre-Trump, a point made in the caption's framing of national parks as valuable and in need of protection. Settle for Biden thus infuses this chronotope with a kind of decency that is indexed by Biden's normativity within the values of that timespace. This example therefore constructs and connects competing chronotopes of class, linguistic pronunciation, knowledge of national parks, and judgements of environmental policies to advocate that its audience vote for Biden.

In the third example, Biden is shown kneeling in front of a classroom chalkboard displaying the words ‘Because a C+ is better than an F’ (Figure 8). Here Biden is implicitly being compared to Trump, with both candidates ranked on a standard US academic grade scale. This post was published at the beginning of September 2020, when debates were underway between Democrats and Republicans about whether schools should reopen as the COVID-19 pandemic raged on, and under what conditions. Biden's mask-wearing in this photo is no doubt a nod to his policy position, popular with the Left, that schools should be reopened only with strict COVID-19 safety protocols in place, including the use of masks (Viser Reference Viser2020). The text of the post caption states, ‘Joe isn't the A we wanted, but we'll settle for a passing grade when four more years of Trump would certainly mean failure’. In likening Trump to an ‘F’ in school, the campaign metaphorically represents him as a ‘failure’ of a president, leading the US into ruin.

Figure 8. Because a C+ is better than an F (Settle for Biden 2020e, published September 9).

Figure 9 vertically represents how Biden and Trump are mapped onto this academic scale. In using the past tense form ‘wanted’ when scaling both candidates against ‘the A we wanted’, the campaign acknowledges the Progressive perspective that Biden is not an ideal choice yet nevertheless defaults to him as the better choice. The judgement implied by the scalarity of the post is based on educational norms for the US middle class (for less privileged students, of course, a C+ may be a grade to strive for and is by no means the norm, whereas an A remains out of reach). The post imagines discerning educated readers as centers of authority who will understand the subtext of the humor positioning Biden over Trump.

Figure 9. Academic grade scale.

The image of the post again constructs an older twentieth-century timespace in a US public school, evidenced by the chalkboard, colorful linoleum flooring, and brightly painted cinderblock walls. Chalkboards are now ‘relics of a bygone era’ in a time when whiteboards and smartboards have become prominent even in rural US public schools (Kankiewicz Reference Kankiewicz2016), and lineoleum flooring looks more ‘retro’ now, reminiscent of the pre-1980s. Importantly, the photo depicts not a wealthy private school, but a school without substantial funding, again associating Biden with the middle instead of elite classes. Biden's age is also on full display in this photo, not only through his indexical relationship to this chronotope but also through his presence in the photo as an older man out of place in a setting designed for children.

Norming Biden through age

As we have already begun to see, the Settle for Biden campaign portrays Biden as normative in relation to dominant ideologies surrounding age relations. In this section, I explore how the campaign manipulates symbols used by the official Biden campaign to highlight young Progressives’ concerns about his older age. The two examples situate Biden within a chronotopic frame of mid-twentieth-century America to index his identity as a politician who is removed from modern America yet nevertheless preferable to Trump. The two examples in focus mock the political messaging of Biden's official presidential campaign as missing the mark, instead humorously acknowledging his inability to connect with younger generations. For instance, in the first example (Figure 10), Settle for Biden evaluates the Biden presidential campaign slogan ‘No Malarkey!’ with befuddlement to acknowledge his distance from younger perspectives. In the second example (Figure 12), the campaign uses imagery of Biden driving his 1967 Corvette Stingray—recalling the gendered trope of a middle-aged man countering a midlife crisis—to portray Biden's mediocrity as the best outcome Americans can hope for when the ‘journey’ of the 2020 election comes to an end. These strategies frame Biden as past his prime yet still preferable to Trump: he is out of touch rather than out of control.

Figure 10. Eh, okay … Maybe just a little malarkey (Settle for Biden 2020f, published September 22).

Figure 10 displays a photograph of a Biden campaign tour bus riding through a snowy landscape. The text on the bus prominently displays the ‘No Malarkey!’ slogan that Biden used in the Democratic Party presidential primary elections, especially during his tour in rural Iowa. Not pictured in the image is text that the Biden campaign printed on the bus defining ‘malarkey’ as ‘insincere or foolish talk’ (Thomas Reference Thomas2019). At a rally in Iowa, Biden explained why his campaign adopted the slogan: ‘The reason we named it ‘No Malarkey’ is because the other guys all lie. So, we want to make sure there's a contrast’ (Korecki Reference Korecki2019). Biden told voters that he chose the slogan because it was a term that his grandfather often used to refer to dishonesty (Thomas Reference Thomas2019), evidence for the strong indexical relationship between the expression and old age.

The slogan received mixed attention from potential voters, often eliciting praise from older generations but mockery from younger generations (Korecki Reference Korecki2019). The term called not only Biden's ‘no nonsense’ stance to the forefront, but also his older age. One young Iowa voter shared her concern with POLITICO: ‘I'm afraid he's going to be disregarded as, ‘Ok, boomer’’. Another nineteen-year-old Iowan shared: ‘He does seem genuine. [But] it's an older word. Not necessarily in touch with younger people’. In contrast, a member of the official Biden campaign remarked, ‘Older people know what it means. And older people vote’. With this post, Settle for Biden thus highlights the disconnect younger voters feel between themselves and Biden. The countering slogan ‘We don't know what exactly malarkey is’ indicates a temporal disconnect between the chronotope indexed by the phrase and the more modern timespace of Progressive voters. Although the phrase was no doubt used by Biden to achieve a middling style, Settle for Biden re-evaluates it as an older, hokey slogan to ‘adequate’ (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2005:599) the campaign's perspective with that of an imagined Progressive readership.

At the same time, the embedded text in the image again adopts a scalar perspective on the slogan: ‘Eh, okay…Maybe just a little malarkey,’ with the word little italicized for emphasis. In this, the campaign makes it clear that it disagrees with Biden but is willing to accept him as its candidate, altering the slogan from ‘No Malarkey’ to ‘just a little malarkey’. This reframing acknowledges that Biden is a candidate voters may not be able to fully believe; they cannot take his slogan at face value, nor can they expect him to always tell the truth. This, however, is a typical view of politicians; Americans tend to believe that all politicians lie to an extent, as deception is a popular tactic in political discourse (McGranahan Reference McGranahan2017; Pfiffner Reference Pfiffner, Lamb and Neiheisel2019). While Settle for Biden calls Biden's honesty into question, it does so in an agreeable way: Biden will be ‘a little’ untrustworthy simply because he is a politician. The campaign therefore allows its audience to join in its skepticism of Biden in a way that is normative for voters: Biden is a regular politician, neither exceptionally truthful nor exceptionally dishonest, and in this middle ground ranks above his competitor (‘We don't know what Malarkey is but we know it's better than fascism’). Trump's lying is unprecedented in its volume and kind (McGranahan Reference McGranahan2017; Pfiffner Reference Pfiffner, Lamb and Neiheisel2019; Hodges Reference Hodges2020), placing him at all but off the charts on a malarkey/dishonesty scale (Figure 11). In sum, Settle for Biden constructs interrelated scales of age and political dishonesty to portray Biden as normatively flawed, casting him as ‘good enough’ to be an American president.

Figure 11. Malarkey/dishonesty scale.

The second example in this grouping (Figure 12) exploits the iconicity of an older white man driving a convertible to invite voters to ‘hop into the moderate-mobile’. Biden is pictured in the post smiling as he sits in the driver's seat of his 1967 Chevrolet Corvette Stingray. Above the photo, the embedded text states, ‘MEDIOCRITY IS ONLY A SHORT RIDE AWAY’. The campaign published three separate posts depicting Biden in his Corvette in August.

Figure 12. Mediocrity is only a short ride away (Settle for Biden 2020g, published August 23).

On August 5, 2020, the official Biden campaign released a video advertisement featuring his Corvette, in which Biden described why he loves the car and posed the question: ‘How can American vehicles no longer be out there?’ (Biden Reference Biden2020). Biden made promises to prioritize the production of electric vehicles, including the first electric Corvette. The ad takes viewers back to an older timespace—based on the age of the car and its prominence as an American icon, particularly among the middle classes. Chevrolet cars have been particularly popular among those in the lower-middle class, especially during the mid-twentieth century (Samuel Reference Samuel2014), and thus the Corvette Stingray, in contrast to a foreign convertible like a BMW, could be seen to index an older, American-born, lower-middle-class US. Originally the most prosperous car industry in the world, US car manufacturing and prestige has faced long-term substantial decline (Murray & Schwartz Reference Murray and Schwartz2019). Therefore, idealizing the Corvette Stingray as a classic American icon, as the official Biden campaign does, is out of touch with Progressive aesthetics of consumption.

The image of Biden driving his convertible also produces him as an exaggerated heteronormative stereotype: an older man driving a sports car. As the domains of driving and cars tend to be associated with stereotypes of manhood, and possessing specific types of cars such as trucks and sports cars is part of masculine heteronormative gender performativity (Avery Reference Avery2012), this image of Biden appeals to a traditional view of masculinity in the US. Owning and driving sports cars and convertibles is also associated with middle-aged identities, especially the concept of the mid-life crisis (Gatling, Mills, & Lindsay Reference Gatling, Mills and Lindsay2014). By referring to the car Biden is shown driving as ‘the moderate-mobile’, Settle for Biden reflects its stance against moderate policies, while it simultaneously invites the audience to ‘hop in… to help defeat nascent fascism’. Given the binary option between the two—moderate policies or fascism—the campaign situates Biden as the obvious and safe option and Trump as a danger to democracy as it also appeals to scalar relations governing class, age, race, and gender.

Conclusion

Through its use of humor, Settle for Biden offered reluctant young Progressives a way to laugh at Biden while voting scalarly against Trump. Its entertaining, easily sharable posts allowed even the most anti-Biden Progressives to share this position across multiple digital platforms. While the number of ‘likes’ assigned to these Instagram posts increased as the campaign became more popular, it is telling that posts more disparaging of Biden tended to receive more ‘likes’ than other posts published around the same time. For instance, the examples which are explicitly insulting to Biden—that is, the post comparing Biden to a ‘C+’ and the post comparing Biden to a ‘foul ball’—are also the two most ‘liked’ of the six posts examined, earning 85,877 ‘likes’ and 18,830 ‘likes’, respectively. Such counts highlight the resonance of deprecating humor for Settle for Biden's audience and explain how a political campaign can win voters by scaling insults toward its own candidate. Settle for Biden was criticized by some for compromising Progressive values in its stance that voters should stay within the US political binary and ‘settle’ for a moderate Democrat. However, the campaign countered by mapping the binary onto an evaluative scale that forced a choice between two undesirable chronotopes: normative or chaotic.

My analysis has demonstrated how a political campaign following the presidency of Donald Trump was able to achieve success by producing a candidate as merely ordinary. Settle for Biden exploits the unmarked power of normativity in the construction of scalar comparisons orienting to centers of authority such as class and age. While Settle for Biden rarely explicitly mentions Trump, the campaign's intertextual strategies evoke Trump when portraying Biden as superior in his mediocrity, even if unpopular among Progressive voters. The chaos, fear, and uncertainty that Trump brought to office made this type of campaign not only possible, but appealing. Trump's unpredictability, combined with the Left's concerns about celebrity politics more generally and heightened fears about the COVID-19 pandemic, drove a shared desire for a return to normalcy capitalized on by the Settle for Biden campaign.

Following the election, the campaign switched gears, losing some of its humorous tone and focusing more substantively on evaluations of Biden's policies and cabinet nominees, ultimately renaming itself ‘Path to Progress’ after the 2021 inauguration. Path to Progress erased all posts from its Settle for Biden days and now focuses on highlighting the dangers of the 2024 Republican presidential candidates. These changes fix Settle for Biden in the unique timespace of the US 2020 election and underscore the abnormal context of the Trump presidency that made the campaign possible.

In the scalar world constructed by the campaign, Biden's normativity proves to be his best qualification for office. This illustrates the importance of the notion that normativity is best viewed as an interactional achievement that is asserted through evaluative scales (Carr & Lempert Reference Carr, Lempert, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019). Crucially, we cannot discuss the campaign's appeal to one type of normativity without its appeal to others (e.g. middle classness, whiteness, heteronormativity), supporting growing work within linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics regarding power as arising from the interconnectedness of normativities (Reyes Reference Reyes2017; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019; Hall Reference Hall2021; Khoo Reference Khoo2023). Settle for Biden also constructs simultaneous competing chronotopes of past and modern US timespaces and appeals to their scalar relations to produce Biden as normative while also mocking his normativity as undesirable. My analysis of the dynamic and interlocking scales produced by the campaign to construct Biden's normativity therefore brings together academic work on normativities as both scalar and interconnected, contributing to growing research on how online interaction constructs and mediates norms and behavior (Sanei Reference Sanei2022).

The chronotopes deployed in Settle for Biden's Instagram posts do not just indexically associate Biden with an older, white, middle-class America—they also call up a time of normalcy and decency that is both pre-Trump and pre-celebrity politics. The campaign transports the audience (alongside Biden) into an iconic America that watches baseball, eats Dairy Queen in a small town, sits in a classroom with a chalkboard, visits national parks, uses old-fashioned phrases, and drives Chevrolet cars like in the 1960s. However, the judgements that these scenarios elicit depend on a privileged white middle-class viewership. Ironically, Trump's 2020 ‘Make America Great Again’ campaign exploits similar chronotopes of an idealized American past, but it does so for different reasons. The intertextual message that emerges from the Trump campaign expresses nostalgia for a time preceding civil rights when sexist and racist acts received less legal scrutiny (Goldstein & Hall Reference Goldstein and Hall2017). The Settle for Biden campaign uses downscaling language and imagery to cast Biden as iconic of a mediocre American ideal, but the Trump campaign uses rhetorical hyperbole to cast Trump as returning us to unregulated white supremacy.

Perhaps the most surprising finding of this article is that a political campaign in our current era of celebrity politics can find success by situating its candidate in the normative area between exceptional and reprehensible. The Settle for Biden campaign's focus on mediocrity stands in sharp contrast to the ways that typical US presidential campaigns use scalar relations to position their candidates as extraordinary, even if down-to-earth enough to ‘have a beer with’. It instead succeeds by constructing Biden as a ‘mediocre’ consumer good who offers a commonsense alternative to the hyperbolic semiotics of a previous president. Biden is cast as ‘good enough’ to be president only in comparison to Trump's excess. Given that we now live in what some call a ‘post-truth’ world with increasing political strife and widespread misinformation (Temmerman, Moernaut, Coesemans, & Mast Reference Temmerman, Moernaut, Coesemans and Mast2019), it is imperative to identify and examine the semiotics associated with campaigns similar to Settle for Biden as they emerge. The legacy of the Settle for Biden campaign continues to live on in the Twitter hashtag ‘#SettleForBiden’, which is now used ironically by voters themselves to express ongoing discontent with the Biden presidency. Given that Trump's announcement of a third White House bid has inspired a new round of behavior increasingly identified by the media as ‘Republican chaos’ (e.g. Cass Reference Cass2023; Rosenwald Reference Rosenwald2023), it remains to be seen how strategies of Democratic normalcy will fare in the future.