No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

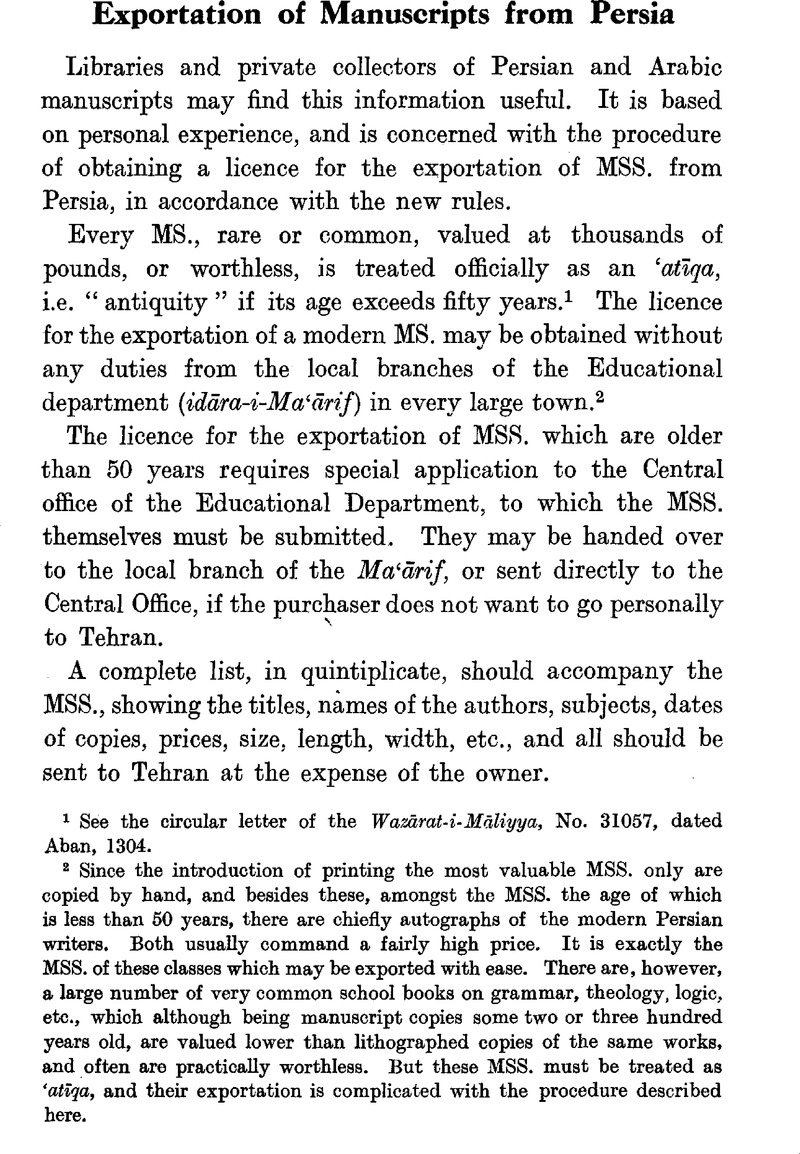

Exportation of Manuscripts from Persia

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Asiatic Society 1929

References

page 441 note 1 See the circular letter of the Wazārat-i-Māliyya, No. 31057, dated Aban, 1304.

page 441 note 2 Since the introduction of printing the most valuable MSS. only are copied by hand, and besides these, amongst the MSS. the age of which is less than 50 years, there are chiefly autographs of the modern Persian writers. Both usually command a fairly high price. It is exactly the MSS. of these classes which may be exported with ease. There are, however, a large number of very common school books on grammar, theology, logic, etc., which although being manuscript copies some two or three hundred years old, are valued lower than lithographed copies of the same works, and often are practically worthless. But these MSS. must be treated as 'atīqa, and their exportation is complicated with the procedure described here.

page 442 note 1 As I was assured in different institutions in Tehran, pilfering from all government libraries is going on briskly. Even the most optimistic Persian officials would not assert, indeed, that the frontier of Persia is perfectly proof against smuggling, or that thieves are necessarily fools who will bring their books for getting an exportation licence. Therefore the elaborate procedure of all these precautionary measures affects chiefly that class of MSS. which present little market value, but may be important later if saved from inevitable destruction.

page 443 note 1 In my case (Shiraz, October, 1928) the representative of the Finance office (a man called Khalwati) kept the director of the local Ma'ārif and myself busy for more than a week, raising absurd objections, before he got courage to confess that he did not understand Arabic and never had anything to do with manuscripts. But he was not as bad as many others, and was regarded as an educated man.