Introduction

Passported benefits, also known as community service cards, free schemes, or household benefit packages, are a key, albeit often overlooked, component in the toolbox of welfare states. Unlike direct cash benefits, which are provided to individuals and families based on diverse eligibility criteria, passported benefits are additional cash or in-kind benefits that augment existing cash benefits. They are “passported” because the sole, primary, or initial determinant of access to these benefits is eligibility for those direct cash benefits. The idea is that people, whose need has already been determined, will receive additional support without being required to undergo arduous bureaucratic processes.

In theory, this fast track should result in easier access to benefits and higher take-up levels and facilitate meeting individual needs and policy objectives more effectively (Kim and Joo, Reference Kim and Joo2020). Paradoxically, however, implementation has often proven problematic because accessing passported benefits requires applicants to overcome additional bureaucratic barriers, resulting in a burdensome experience to the point of non-take-up.

Passported benefits, as well as other forms of “social policy by alternative means” (Béland, Reference Béland2019), have tended to be beyond the scope of welfare state research. Thus, while public expenditure for passported benefits is significant, they have attracted very limited theoretical and empirical scrutiny, and tend to be overshadowed by more traditional policy tools.

This article contributes to existing welfare state knowledge by drawing upon an Israeli case study to offer a more solid conceptual framework for the study of passported benefits. This framework, which assumes passported benefits to be a highly complex and ambiguous tool, depicts them as categorized along five dimensions: the eligibility role of primary cash benefits; automation level; legal status; type of service delivery; and the degree of decentralization. The administrative burden literature is then employed to make sense of the paradox of passported benefits becoming often a site for administrative burden.

Literature Review

Passported Benefits

Passported benefits (or services) are not easily defined, but generally, their receipt is conditional upon the individual already being eligible for a “primary” social security benefit (Social Security Advisory Committee, 2012, p. 43). While described collectively as passported benefits in the UK (Royston, Reference Royston2017), they are called community service cards in New Zealand (Foley, Reference Foley2018), linked benefits in Israel (Eliav, Reference Eliav2011), and free schemes (Nolan and Russell, Reference Nolan and Russell2001) or household benefit packages in Ireland (Department of Social Protection, 2022). In the US, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme (SNAP) and the National School Lunch Programme (NSLP) are passported benefits that offer “categorical eligibility’ (Pinard et al., Reference Pinard, Bertmann, Byker Shanks, Schober, Smith, Carpenter and Yaroch2017).

The limited research on passported benefits offers evidence of their low take-up. Just above half of all families eligible for the UK Healthy Start programme take-up their rights (46%) (Parnham et al., Reference Parnham, Millett, Chang, Laverty, von Hinke, Pearson-Stuttard and Vamos2021). Low take-up is also evident in the US Free School Meals programme, with non-take-up rates ranging between 11% to 33% (Holford, Reference Holford2014; Sahota et al., Reference Sahota, Woodward, Molinari and Pike2013; Patrick et al., Reference Patrick, Anstley, Lee and Power2021). In Israel, take-up of passported discounts on water bills falls below 70% (Dahan and Nisan, Reference Dahan and Nisan2010), and take-up rates for passported local (council) tax benefit ranges between 25% to 75% (Gal et al., Reference Gal, Dahan, Benish, Holler and Tarshish2021).

Several common characteristics of these benefits should be noted. First, in contrast to primary benefits, which are generally provided as an integral part of the national social security system, passported benefits are provided by multiple ministries, institutions and state or local authorities. This is the case in Ireland and the UK (Social Security Advisory Committee, 2012; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2003). In the US, SNAP and NSLP are dependent on the cooperation of state agencies and school districts, respectively. Second, while the social security system often provides universal benefits (Gal, Reference Gal2004), passported benefits are usually targeted at marginalized, low-income populations already found to be eligible for mean-tested benefits (Layte et al., Reference Layte, Fahey and Whelan1999; Nolan and Russell, Reference Nolan and Russell2001). Finally, primary benefits usually provide cash support, while passported benefits are more likely to be in-kind benefits or exemptions and discounts (Horne and Hardie, Reference Horne and Hardie2002; Lyall, Reference Lyall2013; Quinn, Reference Quinn2000; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2003).

As illustrated in Table 1, passported benefits serve as a social policy tool in various countries. They often rely on significant public expenditure that does not fall short of that for some traditional social benefits and services, and they address a wide range of needs. For instance, they provide financial assistance; school lunches and other aspects of the education system; health services, including access to primary health in the community and to subsidized medicine; public utilities; public transportation; and housing. In some countries, passported benefits also offer tax breaks or free legal aid.

Table 1. Passported Benefits in Selected Welfare States

Sources: Parnham et al. (Reference Parnham, Millett, Chang, Laverty, von Hinke, Pearson-Stuttard and Vamos2021) (UK); Dept. of Agriculture (US); Ministry of Social Development (NZ), Israel Electric Corporation (ISR); Dept. of Social Protection (IRL).

Despite being a crucial tool in welfare state toolboxes, passported benefits have received little academic scrutiny. The studies that do exist usually focus on specific programmes and tend to be applied research, leaving us with limited theoretical understanding of the nature of this unique tool. This gap is problematic, not only due to the expansive use of passported benefits, but also due to their complexity and ambiguity. Thus, eligibility tracks for passported benefits are diverse. Some programmes provide fast-track eligibility to those receiving other primary benefits, while in others, populations such as low-income families who do not receive primary cash benefits may also be eligible through a separate, non-passported track. Similarly, while eligibility for primary cash benefits is often a sufficient condition for passported benefits (as in the case of school lunches for most eligible pupils in the US), in many other cases potential recipients can be subject to additional requirements (Lyall, Reference Lyall2013).

The complexities of passported benefits are enhanced by the fact that they are provided in a decentralized manner, by diverse institutions, at the local or state level, and in some cases without clear eligibility rules, or based on the discretion of officials or professionals (Gal et al., Reference Gal, Dahan, Benish, Holler and Tarshish2021; Lyall, Reference Lyall2013; Social Security Advisory Committee, 2012). Thus, unlike the visibility of primary benefits, and much like tax expenditures, passported benefits can be considered a “hidden” part of the welfare state (Howard, Reference Howard1997).

Administrative Burden

In order to make sense of the often-cumbersome process of accessing passported benefits and their low take-up (Gal et al., Reference Gal, Dahan, Benish, Holler and Tarshish2021; Social Security Advisory Committee, 2012; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2003), we draw upon the administrative burden scholarship (Masood and Azfar Nisar, Reference Masood and Azfar Nisar2021). This literature seeks to explain the experiences of claimants in the bureaucratic encounter, or more precisely, the friction between them as a by-product of this encounter, its rules and procedures (Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2019). Administrative burden is “an individual’s experience of policy implementation as onerous” (Burden et al., Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2012, p. 742). Following Moynihan et al. (Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015), these onerous experiences are usually divided into: (1) Compliance costs, that address the need to comply with rules, regulations and requirements; (2) Learning costs pertaining to the need to collect information on the process; and (3) Psychological costs, which refer to the emotional experiences of burden, the negative feelings, the stigma, and the loss of personal autonomy in the process (Baumberg Geiger et al., Reference Baumberg Geiger, Bell and Gaffney2012; Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2019; Walker and Bantebya-Kyomuhendo, Reference Walker and Bantebya-Kyomuhendo2014).

A key goal of the emerging administrative burden scholarship, and the starting point of the current research, is an examination of the formal and informal state actions responsible for shaping the burdensome experience. The assumption is that the design of benefit programmes has profound consequences for access to them (Barnes, Reference Barnes2021; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Malbon and Blackwell2021).

The Israeli Case Study

This article offers insights into the complexity of passported benefits and generates a conceptual framework for their analysis based on an Israeli case study. It shows why a policy tool commonly portrayed as facilitating access to social benefits (Kim and Joo, Reference Kim and Joo2020) often leads to a greater administrative burden and additional take-up barriers. Our key insight is that there is no single “passported benefit”. Rather, it is more useful to address different kinds of benefits. While some are more user-friendly, others tend to become burdensome. Following our analysis, we provide some key insights on how to make these benefits achieve their original goal as a fast track to social rights.

Methods

Data on passported benefits were gleaned primarily from laws, administrative regulations, and documents from the National Insurance Institute (NII, Israel’s social security agency), ministries, state corporations, and municipalities. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2019 and 2020, face-to-face and via Zoom, with 20 officials in state agencies and municipalities. The interviews, conducted by the first author, sought to gain additional knowledge on passported benefits, particularly with regard to the take-up process itself, eligibility criteria and underlying informal practices by claimants and bureaucrats.

Data on administrative burden experienced in practice were collected through semi-structured interviews in 2019 and 2020, face-to-face, via phone and Zoom, with 12 claimants. These interviews, conducted by a research assistant, employed a structured interview guide, but participants were also encouraged to add any additional information that they felt could contribute to the study.

Claimants were recruited through convenience sampling, followed by a snowball sampling phase to achieve theoretical saturation. The recruitment was nationwide, with the main inclusion criteria being a previous successful claim for a NII programme that grants a passport to other benefits. Participants were recruited using direct and personal contacts with NGOs, municipalities and other take-up agents, leaflets handed out in several NII offices and Facebook groups devoted to NII discussions. We ensured that two distinct cultural groups were represented in the sample: ultra-Orthodox Jews and Muslim Arabs. The participants received a formal description of the study and its goals and signed informed consent. Anonymity was assured through anonymization of the full data set.

The data from the claimants’ interviews were analyzed thematically (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) using top-down and bottom-up strategies. The analysis was driven by the five key dimensions of passported benefits (see below), inductive analysis was conducted in order to understand how each dimension was realised in the take-up process and contributes to the experience of administrative burden. The study received ethical approval from the ethics committee at the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Varieties of Passported Benefits in the Israeli Welfare State

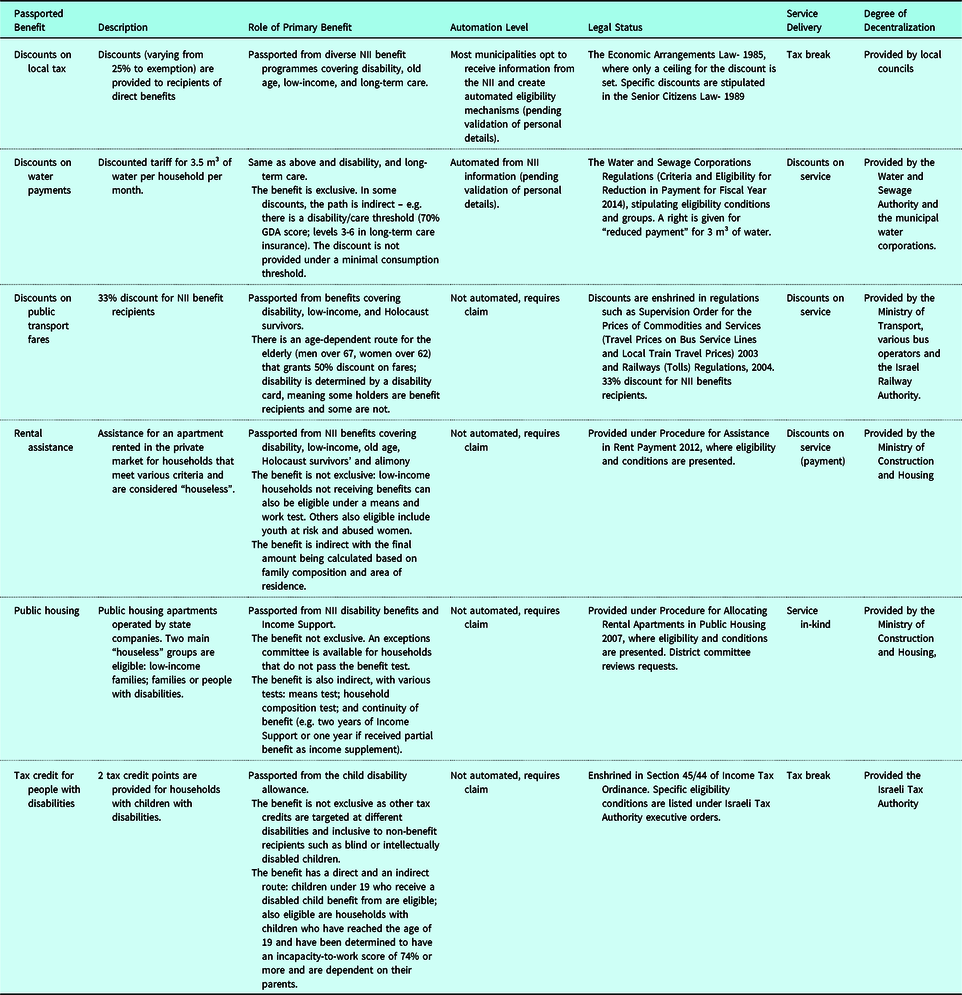

As in other welfare states, passported benefits are a key tool in the Israeli welfare state. In terms of public expenditure, the resources devoted to two key passported benefits – local tax discount and rent assistance – suggest an estimated expenditure of over 900 million pounds, surpassing the expenditure on unemployment insurance programmes. In terms of scope, these benefits cover various needs and areas, including transportation, medication, housing, electricity, water, and tax breaks on property taxes (see Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of Passported Benefits in Israel

The Israeli case presents a complex array of passported benefits. Analysis of their design reveals that they vary along five key dimensions: the eligibility role of primary cash benefits; automation level; legal status; type of service delivery; and the degree of decentralization. The dimensions are described below. A subsequent section will discuss administrative burdens in each dimension.

Eligibility

While the notion of passported benefits is that a primary benefit offers entitlement to an additional benefit or service, in the Israeli case there are rarely no additional conditions. This approach reflects the broader move towards welfare conditionality, which limits access to public goods to those who meet certain conditions (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2019). Therefore, a more nuanced analysis of the primary benefit’s role should differentiate between direct and indirect tracks to eligibility. In the direct track, eligibility for the primary benefit suffices; while the indirect track implies that there are additional requirements or eligibility tests. For example, eligibility for a disability allowance is a passport to some benefits, pending additional eligibility tests (e.g. local tax or public transport discounts).

Moreover, eligibility for the primary benefits is sometimes not the only path for receiving the additional benefits or services. Thus, another distinction is between exclusive tracks, in which only claimants receiving the primary benefit qualify and non-exclusive tracks, in which other claimants, not eligible for the primary benefit, may also be eligible for the same benefit or services through a parallel route. Such is the case of local tax discounts; households can claim the discount either as a passported benefit due to previous eligibility for Income Support or through a designated non-passported route for low-income households, based on means tests (Dahan, Reference Dahanforthcoming).

Automation

The level of automation relates to the degree that the eligibility for the passported benefit does not require any action by the claimant. Automation is mainly relevant in the case of direct track benefits. However, direct track benefits vary between automated and non-automated benefits. The former ensures that when a household becomes eligible for a primary NII benefit, the passported benefit is provided automatically following information validation. Such automated benefits are available, for instance, in discounts on water and electricity, in which mechanisms have been developed to grant automated approval, building on information transferred to utility companies from NII databases. Non-automated direct track benefits require eligible households to actively claim the benefit. This is the case for rental assistance, discounts and exemptions for health-related conditions and discounts on public transport fares.

Legal Status

The legal status of passported benefits differs. They can be provided on the basis of laws, by-laws, regulations, administrative rules, and other formal arrangements. For example, the Water and Sewage Corporations Act of 2001 and its bylaws stipulate discounts on water payments for NII benefit recipients, but rental assistance is based on Ministry of Housing directives. This may influence the durability of these rights in terms of the policymakers’ capacity to revoke them or change their eligibility criteria. Passported benefits may also differ in terms of ability to apply for administrative or judicial redress in case of eligibility denial.

The level of discretion devolved to localities and to street-level bureaucrats during implementation is crucial. For instance, mandatory local tax reduction for recipients of old age benefits is based on the Senior Citizens Act of 1989. However, other local tax reductions are provided as a non-mandatory discount, subject to the discretion of the local government (up to a maximum legal ceiling). These often grant bureaucrats considerable discretion in the eligibility decision-making process.

Service Delivery

There are four types of service delivery. Services in-kind include, for example, respite care and childcare services for children with disabilities who are eligible for a child disability allowance. Less common is cash assistance. It includes Ministry of Housing grants for home improvements for people with mobility problems, scholarships for students receiving disability benefits, and cash assistance for Holocaust survivors eligible for long-term care benefits.

A third type of service delivery – the most common in Israel – is charge reductions or exemptions. These include discounts on various household payments such as internet and telephone line costs, water, and electricity and various discount plans for transportation services. This delivery method is a compromise between in-kind services and cash assistance.

Finally, tax breaks include reductions in specific taxes, primarily local ones, provided to recipients of income support, disability, and old age benefits. Alongside specific tax breaks, the parents of children with disabilities receiving a child disability allowance are eligible to general income tax credit points.

Decentralization

The last dimension does not refer to a specific benefit but rather to the entire configuration of the passported benefits system. A key aspect of decentralization is the degree to which these benefits are provided by different agencies. In the Israeli case, the providers range from central government (such as the Ministry of Welfare and Ministry of Housing), local government, public corporations (such as local water suppliers), and for-profit agencies (such as the Bezeq telecommunications company). This high degree of decentralization is evident in the fact that the same primary benefit can be linked to a range of different providers. For example, the NII old age benefit is a passport to benefits and services by municipalities, Bezeq, water corporations, the Israel Electricity Corporation, the Ministry of Housing, and the tax authority.

Another aspect of decentralization is the degree to which the central government, particularly the agency responsible for the primary benefit, takes a lead role in managing the system. This can take many forms, from sharing databases with local agencies to actively providing information to potential entitled citizens. In Israel there are only partial state-level mechanisms for the transfer of citizen data. For example, only some municipalities opt to receive the claimant information from the NII required to streamline the process of local tax discounts (State Comptroller of Israel, 2015).

Passported Benefits as Sites of Administrative Burden

Passported benefits evolved ostensibly to offer additional support to people in need by streamlining their access to additional benefits or services. In practice, however, the literature attests to considerable barriers to their take-up, stemming from costs such as lack of information, stigma and the value of the benefit (Dahan and Nisan, Reference Dahan and Nisan2010; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2003). These findings suggest the conflicted position of passported benefits, where a programme intended to streamline access is plagued with administrative burdens. In this section, we delve into this conflicted position to offer a more nuanced understanding of passported benefits as sites of administrative burden. Participants’ quotes in this section reflect common themes and patterns emerging from the interviews (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). These individual quotes, the result of a thematic analysis of interviews with claimants, mirror the systematic experiences of administrative burden cited by the claimants.

Eligibility

The divergent role of the primary benefit from which eligibility is passported is a key potential factor in shaping passported benefits’ administrative burden. When the primary benefit serves as a direct passport to a benefit, this naturally reduces burden. The direct route avoids additional tests and requirements that culminate in learning and compliance costs. Moreover, as some psychological costs, particularly autonomy and stress, were found related to changes in compliance demands, this direct route has also the potential to relieve some of the negative feelings people experience in the encounter with bureaucracy (see Baekgaard et al., Reference Baekgaard, Mikkelsen, Madsen and Christensen2021).

When this is not the case, and passported benefits are indirect, claimants must not only be familiar with the additional rules required for eligibility, but also with the disappointment entailed by the fact that they anticipate their eligibility for a primary benefit to also entitle them to passported benefits, leaving them confused as to why they are not automatically eligible. Eviatar m, 59, GDA recipient), for example, receives a disability care allowance, which entitles beneficiaries requiring extensive care to a discount on electricity costs. When asked which passported benefits he received, he recalled that he had contacted the Israel Electricity Corporation to inquire regarding a discount on electricity payments, but did not receive the benefit due to even more eligibility conditions than he was unaware of, leaving him frustrated:

Because they told me that they checked and I’m not eligible, only those with over 100% (care support need) or something like that [are], and that I must explain why I need more electricity because of machines such as respirator machines […]. I understood that they want to complicate things here, so I backed off and that was that.

Moreover, when passported benefits also include a non-exclusive track, they are often trickier to understand and apply for, critically increasing the learning burden for claimants both with and without a passport. Tom (f, 40), a single mother who receives Income Support, discussed the learning burden she experienced when applying for a non-exclusive track benefit – a discount on local tax due to her low income and status as a single parent. She had not been aware of an application track that eventually doubled her benefit level. Referring to friends with a similar problem, Tom said:

Regarding the local tax I learned it from friends who are also single mothers. They got a 40% discount and I got 20% from the beginning. And then I heard that you get 40% if you apply to a special committee. I can share that in the last two years I have done this and received it (40% discount).

In her case, receiving the discount not through the fast track was eventually more rewarding, and she found out about it only after taking the fast track.

Automation

Automation is another key factor affecting administrative burden. By automatically allocating the benefits based on information provided by the NII to the relevant agency, compliance and learning costs are significantly reduced. An illustrative example is Netta’s case (f, 53). Netta, who receives a disability benefit, explained that, after the automatization of the process of taking-up local tax discounts, she no longer has to actively claim the discount but only to ensure that she receives the correct amount: “For several years now, I have not been asked [to go through the process] every year […].” Automation was sometimes experienced as fully burden reducing. Another example is Vlada (f, 82, Old-Age benefit recipient), who did not even know that she received automated passported benefits, discounts on water and electricity, until the benefits showed up on her bill: “I didn’t receive any message or know who sent them or gave them [my details]. Nothing”.

Nonetheless, automation is not devoid of limitations. Flaws in automation design can lead to large-scale errors (Henman, Reference Henman, Hertogh, Kirkham, Thomas and Tomlinson2020), creating new administrative costs, even to the point of creating financial debts, such as the case of robo-debt in Australia (Carney, 2018; Reference Carney2020). Secondly, in atypical cases that are excluded from automation, it can intensify the administrative costs (Larsson, Reference Larsson2021), particularly for population groups with low technological literacy.

Thirdly, burden in the automation processes can also intensify. This occurs when eligibility to automated benefits depends on characteristics of other members of the household, as in some of the local tax benefits. Another example is a slow process of information validation after a claim to a direct benefit is approved. Relatedly, information validation, particularly in atypical cases, is prone to errors (e.g. when the electricity bill is listed under a different name than the claimant’s). These errors are often difficult to detect and can in turn create additional administrative burden by requiring claimants both to understand that an error had occurred and to take active actions to correct it (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2022; Widlak and Peeters, Reference Widlak and Peeters2020). For example, Reut was “absolutely drained by the bureaucracy”. She was sure she already received the automated electricity payments discount, but found out she paid the full rate for years and had to actively intervene and contact several authorities to amend the error:

I didn’t bother to check it because I have a standing order, and after two years I received a letter … and suddenly found out that nothing is updated. I spoke with the electricity company and they told me they can’t do anything and that I have to contact the NII and ask them to submit my qualification to the computer. Turns out I haven’t received the discount for two years!

Legal Status

When the passported benefit is supported by a well-structured legal framework, this usually solidifies the eligibility conditions, the process, and tests required, and allows the potential claimant to gather information on the passported benefit and to make an informed decision whether to claim it. This is all the more so when avenues for administrative and judicial appeal are in place. Netta, for example, explained how via the appeal committee she was able to mend a previous error and to reduce some of the burden she experienced in the process of taking up ‘accompanying benefit’ for people with visual impairments:

They […] decided I’m not eligible. It took me months until some girl told me to go to the appeal committee, means to go to the hospital to some eye doctor that took a look at me and told me ‘what, I don’t know why they had to bother you to come here. You are eligible, and I got the benefit. They did me a favour and gave me the benefit retroactively since I submitted the letter, what can I do… so I only lost 5-6 months […] it was annoying, you already decided I’m eligible, and I know I am.

However, the legalization of the benefit may sometimes create barriers to take-up by making the process much more formalized and consequently increasing compliance and psychological costs. This is particularly the case when policymakers deliberatively design bureaucratic procedures and access requirements to restrict or deter access to passported benefits (Herd and Moynihan, Reference Herd and Moynihan2019).

A similar dual effect may arise from discretionary aspects of service delivery. Often discretion is seen in the administrative burden literature as an obstacle to take-up – increasing arbitrariness and bias in the administrative process (Peeters, Reference Peeters2020). When discretion is delegated to localities, they may choose to not provide the benefit, potentially eliminating the right to service. When discretion is delegated to street-level bureaucrats, they can act “against clients” by creating administrative burdens (Evans and Harris, Reference Evans and Harris2004; Evans and Hupe, Reference Evans and Hupe2020). When discretion is “towards clients”, it can lead to a more empathetic approach (Maynard-Moody and Musheno, Reference Maynard-Moody and Musheno2000), supporting take-up and introducing flexibility and responsiveness into rigid bureaucratic systems. This dual effect requires us to consider not only the degree of discretionary power available to street-level bureaucrats but also the conditions that shape its use, including organizational (e.g. training and guidance), worker (e.g. values and beliefs) and socio-political (e.g. insufficient resources, workload) factors.

Service Delivery

As discussed above, passported benefits are provided to claimants as services in-kind, reductions or exemptions from charges, monetary assistance or tax breaks. Clearly, the type of service delivery affects the administrative burden experienced throughout the process. Provision of passported benefits as services in-kind leaves less autonomy to claimants and can be considered more stigmatic – two crucial components of administrative psychological costs (Bielefeld, Reference Bielefeld2021; Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015). In the case of voucher-based services, they may sometimes be also subjected to “redemption costs”, emphasizing the limited portability of services and the reliance on third-party agents as burden-inducing (Barnes, Reference Barnes2021). This type of limited portability is evident for example in the case of Vlada, who explained how a benefit offered to her was not tailored to her needs: “They did not give me any opportunity at all, to ask what suits me or doesn’t suit me […] go check, see if it suits the person”. Such an effect may be less evident in reductions or exemptions, monetary assistance or tax breaks. Nonetheless, benefits provided through the tax system are less transparent, with potential direct, adverse impact on learning costs.

Decentralization

Passported benefits take-up is also shaped by the system’s degree of decentralization, which refers firstly to the varieties of providers. As the Israeli case shows, the passported benefits of a single primary benefit are often provided by a number of separate providers, each with its own take-up process. As long as these processes are not automated or at least direct, the consequence is that potential claimants have to deal with multiple claiming processes, thereby experiencing higher compliance and learning burdens, such as filling-in forms, learning of eligibility and procedures and experiencing waiting times (see Bielefeld, Reference Bielefeld2021; Holler and Tarshish, Reference Holler and Tarshish2022) and psychological costs such as stigma and feelings of lack of deservingness. In addition, having to go through multiple processes requires them to gain considerable knowledge about different claiming processes, sometimes even for marginal benefits, thus creating a heavy learning cost (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2015), potentially leading to non-take-up. This was the case of Naama, (f, 27), who receives Income Support and encountered burden when trying to submit claims to the many passported benefits to which she was eligible (local tax, electricity payments discount, water payments discounts and the discount on public transport fare):

To start collecting paperwork from many places and start proving here and there… to dedicate yourself and to collect and then to get stuck in bureaucracy. It’s not that simple. It’s not that you give the documents and they approve your claim, it doesn’t work like that, every entity is something else.

The learning cost, described by Naama as well as other participants, is even more pronounced since mechanisms, eligibility conditions and tests that evolve over time tend to become intricate and provider specific (e.g. household composition tests), consequently forcing claimants to collect tailor-made knowledge regarding their status and ability to fit into one of the eligibility routes. This was the case, for example, with Reut (43, f, Income Support recipient), who was involved in several application processes for passported benefits and was not sure whether she could apply to a passported benefit based on lack of tailor-made knowledge. She was certain that due to her relatively low disability score, she could not qualify for either of the passported benefits she was familiar with:

With the 80 percent now, I think I’m not entitled to any benefit, I mean if I’m over 83 percent […]. I don’t I know… Just how to deal with all this stuff… I just give up ahead of time.

The role of government in managing this variation in providers is crucial. If the agency responsible for the primary benefits does not provide its beneficiaries with information about their potential eligibility for passported benefits, this results in learning and psychological costs. The following quote by Samira (73, f, IS for old-age recipient) illustrates how many participants experience such learning costs:

She only answered about what I asked. I asked about local tax discount, and she answered about the local tax discount. Apart from that, she didn’t say anything about the discount on electricity payments, I knew before, the NII didn’t let me know at all.

Conclusion

An Israeli case study shows that a better understanding of passported benefit programmes requires us to focus on five key dimensions: the eligibility role of primary cash benefits; automation level; legal status; type of service delivery; and the degree of decentralization. Drawing on these various dimensions and the data collected, we have shown that some benefits are indeed straightforward and have the potential of providing a fast track to the welfare state “promised land” (Holler and Benish, Reference Holler and Benish2022), but this is not always the case. The complex nature of the system, which is composed of an array of benefits with diverse and often contradictory administrative logics, in of itself poses administrative burden that requires claimants to develop expertise and request assistance if they wish to successfully complete the process (Tarshish, Reference Tarshish2022). Consequently, the track becomes slow and the risk of “administrative exclusion” increases (Brodkin and Majmundar, Reference Brodkin and Majmundar2010).

This Israeli case study contributes to existing knowledge on passported benefits in that it classifies and categorizes this type of benefit. To date, these benefits have tended to be studied employing a lens that focused on specific benefits (such as Free School Meals, Healthy Start vouchers Programme) (Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Jones and Reicker2011; Parnham et al., Reference Parnham, Millett, Chang, Laverty, von Hinke, Pearson-Stuttard and Vamos2021; Sahota et al., Reference Sahota, Woodward, Molinari and Pike2013), rather than on the broad type of benefits in question. This study focuses on passported benefits as a whole and shows that the benefits vary along the above dimensions. In addition, the findings indicate that changes in either dimension may completely alter the service provided to claimants, and have the potential, contrary to previous belief, to increase administrative burdens experienced by claimants (Gal et al., Reference Gal, Dahan, Benish, Holler and Tarshish2021).

Moreover, the findings demonstrate the intricate nature of passported benefits, where the burden created does not divide equally (see, for example, Chudnovsky and Peeters, Reference Chudnovsky and Peeters2021; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Aarøe, Baekgaard, Herd and Moynihan2020). A decentralized approach, for instance, reduces burden by allowing agencies to adapt requirements and processes to the local population (e.g. language) while also reducing travel distances. In practice, the execution of decentralization in passported benefits could increase burden, prolong processes and, crucially, detrimentally impact the most underserved populations, who are usually eligible for more than one passported benefit. Similarly, while automation is beneficial to most claimants, for a-typical cases and for claimants lacking technological literacy it can prove burdensome. Indeed, these groups of service users are also those least likely to express their criticism and feedback regarding administrative burden (Gilad and Assouline, Reference Gilad and Assouline2021). Thus, they tend to be overlooked by policymakers when taking action to reduce burden.

The findings of this study also highlight what can be done to maintain the utility of passported benefits. Simplification of the eligibility rules and tests is essential. It can ease the claimant’s path to take-up and prevent errors in the process. This could be achieved by strengthening the automation of these take-up processes. Automation saves resources, prevents the creation of barriers to take up and administrative burden and limits the ability of bureaucrats to exercise personal judgment. However, automation can also create new barriers to excluded populations as it depends on transfer of information between authorities and requires a method of claimant identification. Hence, system flexibility with regard aspects of information verification is also needed. This can be achieved by introducing multiple methods of automatic verification or by enhancing information sharing between different providers of passported-benefits and other governmental agencies. Finally, the unification of take-up processes to create ‘rights-clusters’ for different population groups that require a single eligibility will limit providers’ judgement in the process and free claimants of the necessity to engage simultaneously in multiple take-up processes of passported benefits.

Altogether, these dimensions, pending additional research and validation, offer a unique opportunity to develop tools to assess burden in passported benefits. These tools can be developed along the lines of RIA (regulation impact assessment) (Wegrich, Reference Wegrich and Levi-Faur2011), so that any proposed passported benefit will undergo an assessment of burden to decide if it can be implemented successfully. In cases in which burden exceeds the benefit, automation processes are to be stipulated. Another possible required condition is that in the case of non-automatic benefits, a dedicated budget for active application assistance be created (Bettinger et al. Reference Bettinger, Long, Oreopoulos and Sanbonmatsu2012). However, to pursue this type of assessment, more research is needed, especially studies that identify levels of burden intensity in allocation of passported benefits, to better inform research and policy.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.