1. Introduction: policy concerns and conceptual issues

‘our great movement of charities and social enterprises. . . .that civil society

. . . I believe we should treasure deeply’

PM Theresa May, ‘Shared Society’ speech at the Charity Commission, 9 January 2017

The development of evidence and argument concerning how voluntary organisations contribute to social policy has a long pedigree in the UK, with key contributions to be found in Social Policy Association journals (Billis and Glennerster, Reference Billis and Glennerster1998; Lewis, Reference Lewis2005). Recently, the combination of recession and austerity policies experienced in the UK since 2008 has made the issue of how communities might cope with rising social needs through voluntary action one of heightened salience. Politically, the assumptions of the post-2010 governments have been that more can be expected from voluntary organisations in this situation, a sentiment underlying the epigraph to this paper. But to what extent are such aspirations now realistic? And are voluntary organisations able to respond without compromising desirable characteristics, including their mobilisation of volunteers, and multi-purpose functioning?

Since the 2007/08 crisis, such questions have received only limited attention from social policy analysts. Broadly, two entry points can be discerned in the literature. First, reference is made to how the generosity of public-welfare-related spending up until the end of the previous decade contrasts with the pattern of constraints and cuts which have prevailed since (see Lupton et al., Reference Lupton, Burchardt, Hills, Stewart and Vizard2016). Building on this contextual observation, writers have pointed to the adverse effects of such post-crisis austerity policies in constituting the external policy environment for those voluntary organisations that had positioned themselves as ‘partners’ with the State. The challenges encountered by those attempting to progress partnership working with local government, especially when also funded by it (this tier of the state having been particularly badly hit by fiscal retrenchment), have been thematised in these studies. Fields examined include social care, housing, and economic and community development (Rees and Mullins, Reference Rees and Mullins2016; White, Reference White2016; cf. Wolch, Reference Wolch1990). Latterly, in the Journal of Social Policy, using qualitative methods and deploying the critical tools of new institutional and governmentality theory, Milbourne and Cushman (Reference Milbourne and Cushman2015) showed how, notwithstanding the adverse financial and political climate, some organisations have been able, with appropriate external support from local state institutions, to develop strategies for survival.

Second, other commentators have focused more on the internal resources at the disposal of voluntary organisations. The best-known evidence on aggregate trends in the funding of voluntary organisations has been the National Council for Voluntary Organisation's (NCVO's) Almanacs, which have recently (e.g. Crees et al., Reference Crees, Dobbs, James, Jochum, Kane, Lloyd and Ockenden2016) shown the collapse of non-contract-based income, and even a negative trend in contract income, for most of the post-crisis period (2016: 29). However, there are countervailing trends, such as an increase in total income in 2013/14 for the first time since 2009/10 (2016: 23), driven largely by heightened levels of trade and (mission-related) commercial income. Furthermore, indicators of the robustness of some non-statutory sources of income, such as the growth of private giving, are evoked to demonstrate the overall sector's ‘resilience’ which, when combined with evidence as to stability in volunteering rates, suggests ‘reasons for optimism’ (2016: 9). This is a relatively upbeat overall narrative from the ‘trade association’ for the sector, which has an interest in accentuating the positives of aggregate developments to ensure that its overall image is confident and coherent. It has been challenged accordingly by ‘rejectionist’ critics as wildly over-optimistic. Using primarily local case study materials, these commentators claim that the NCVO analysis is over-generalised, insensitive to the harsh realities of the irreplaceability of the withdrawn public funds for many organisations, and blind to the constraints on community development and advocacy associated with austerity policies’ implementation. This is especially true for smaller voluntary groups (Aiken, Reference Aiken2015; Benson, Reference Benson2015). Empirically, other national and regional investigations confirm a markedly uneven and variegated pattern when it comes to financial resource trends, including scholarly work recently published in this journal (Clifford, Reference Clifford2016; Chapman, Reference Chapman2015). This mixed evidence shows that, while some fields, types and sizes of organisations have experienced serious financial constraints as austerity and associated policies unfolded, others have apparently stabilised, adapted or even flourished. These studies have generally emphasised financial resource inputs with, in Chapman's studies, occasional future-oriented questions as to perceptions of supply of volunteers.

This paper seeks to broaden further the scholarly understanding of the range of impacts of austerity and recession on individual voluntary organisations, paying attention to both the external policy environment and the internal resource situation. In particular, while recognising that funding issues are of central importance, we also seek to examine the significance of the non-financial resources available to voluntary organisations, and their perceptions of the environment in which they are operating. While the budgets and monetary values associated with organisations, and mapped using administrative data (e.g. Clifford, Reference Clifford2016), are clearly crucial, non-financial resources, or ‘non-resource inputs’ are also materially supportive of social policy activity in two ways. Firstly, through the direct, material ‘production of welfare’, which can be captured using objective indicators (Knapp, Reference Knapp1984). Secondly, in order to flourish, organised actors must share an intersubjective sense that they can deploy resources in support of the activities, outputs and outcomes which matter to them and which involve the enactment of their values and commitments. Such a sense of freedom to express values and convert them into activities involves the existence of a robust, subjective sense of the legitimacy of, and recognition for, those activities. This is important to sustain the substantive motivation of an organisation's workforce, and the identity and sense of purpose of the organisation.

Generally, precedents for this combined attention to material resources – and the symbolic dimension – can be found in the synthetic organisational theory of Hatch with Cunliffe (Reference Hatch and Cunliffe2013). Our approach also resonates with recent sociological and policy process theorising, wherein attention is devoted to both experiential meanings and scarce material resource realities (Fligstein and McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012; Sabatier and Weible, Reference Sabatier and Weible2014). Such frameworks are highly relevant to the particular case of English voluntary sector organisations coping with an austerity situation.

With this in mind, we focus on two particular concerns. The first is the relevance of volunteers as a fundamental ‘non financial resource’ for the voluntary sector as we conceptualise it here, for three reasons (see Kendall and Knapp, Reference Kendall and Knapp2000, for a fuller account of how the sector can be understood as meeting social needs in terms of the ‘production of welfare’). In the specific context of austerity policies, volunteering was seen as one part of the ‘Big Society’ agenda that, according to supporters, offered a ‘human face’ to the necessities of fiscal retrenchment. However, for its critics, it provided ideological cover for brutal cuts while reflecting rhetorical vacuity (Ishkanian and Szreter, Reference Ishkanian and Szreter2012; Corbett, Reference Corbett, Foster, Brunton, Deeming and Haux2015). Furthermore, speaking symbolically and at the macro level, the very language of ‘the voluntary sector’ that has proved so persistent in this sphere in the British case (albeit with varying rhetorical emphases) points to the importance of volunteers for the identity and subjective sense of position of these organisations. This has been seen as an existential matter historically (Kendall and Knapp, Reference Kendall and Knapp1996), and this understanding persists (Small, Reference Small2014). Its conceptual centrality is relevant to social policy, because it means the traditional public policy tools of legal coercion associated with the State on the one hand, and financial incentives associated with the market on the other, will tend to have more limited applicability, in terms of steering behaviour, than in other contexts (Kendall, Reference Kendall2003, chapter 10; Salamon, Reference Salamon2002; Kendall, Reference Kendall, Freise and Hallmann2014). In addition, the internal governance of these organisations, most obviously through the role of unpaid trustees at board level, depends (with a small number of exceptions) on volunteerism. This has been recognised in policy discussions, even since the ‘Big Society’ policy framing has lost political traction (compare House of Commons Public Administration Committee, 2011 and 2016). And although volunteers are to be found elsewhere in the welfare state, this sector is the primary conduit for organised volunteer effort (Kendall, Reference Kendall2003). While there are accounts which stress relative stability in rates of volunteering (Lindsey and Mohan, 2018), tempered by acknowledgement of the impacts of recessionary conditions on involvement (Lim and Laurence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015), we are not aware of academic discussion regarding the extent of volunteer recruitment challenges for voluntary organisations.

Our second chosen focal point is the overall nature of the ‘third sector policy environment’, or key aspects of the ‘climate’ from the subjective perspective of the organisations themselves. It is important to look beyond simply charting material resource dependencies to examine actors’ perceptions, because understandings of framing policy and practice discourses affect motivations and organisations’ sense of their identities (see Hatch with Cunliffe, Reference Hatch and Cunliffe2013). It is in relation to perceptions of the character of the state policy environment that we find what is often seen as a further truly existential consideration, alongside voluntarism: the extent to which this environment is believed to recognise and legitimate the sector's capacity to operate multi-functionally. This is in keeping with Hatch with Cunliffe's (Reference Hatch and Cunliffe2013) general claim about the joint significance of both material and symbolic dimensions for organisational life, and the idea that all organisations are in some sense ‘value based’ (see Mayo, Reference Mayo2016). But we are going beyond this to suggest that, specifically in the third sector case, we should proceed on the normative assumption that values can potentially be expressed and supported in both service delivery and discursive processes oriented across diverse communities of place, interest and commitment. Furthermore, the existence of stable opportunities to put such values into practice systematically, confidently and in a publicly visible way is crucially important in rendering the notion of a ‘third sector’ meaningful (see Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Mohan, Brookes and Yoon2017 for a discussion of the basis for this claim).

Accordingly, the paper proceeds as follows. In section 2, we outline the mixed methods we have used in the applied research while pursuing these issues. Sections 3 and 4 then report and discuss the findings, based respectively on insights gathered from a small group of recognised national policy experts drawn from the third sector ‘policy community’ and an online survey seeking to describe and model the relevant dimensions of concern to in-scope social policy charities. The results are suggestive of a complex situation, significantly more troubling than the optimistic narrative of ‘resilience’, but yet not as uniformly bleak as might be inferred from the apocalyptic tone of some counter arguments.

In what follows, we will tend to use ‘voluntary sector’ as shorthand for the English social policy voluntary sector, to refer to a particular subset of these organisations: charities operating in one of five core fields of social policy. Consistent with the wider concerns of the European comparative project, of which this work formed part, these fields are the following subsectors of the International Classification of Nonprofit Organisations (ICNPO: Salamon and Sokolowski, Reference Salamon and Sokolowski2016): health; social services; economic, social and community development; law and advocacy; and ‘Philanthropic intermediaries and voluntarism promotion’. Applied in Britain, the latter category includes voluntary sector infrastructure bodies, responsible for promoting voluntary action locally. Out of scope are therefore such well-known charities as those focussing upon environmental issues, culture and arts organisations, overseas development and relief agencies, and privately funded or publicly maintained educational establishments.

2. Sources and methods

We deploy mixed methods, drawing upon the English component of a European study which examined ‘third sector impact’, including the ‘barriers and opportunities’ to its realisation (see http://thirdsectorimpact.eu). The substantive focus of the study encompassed quantitative work on indicators of contemporary changes and challenges being experienced by the sector; in-depth qualitative research undertaken with members of the third sector policy community as well as with individual organisations; and survey research concerning organisation-level variations in perceptions of their operating environment.

In section 3 we consider the views held by key stakeholders in the third sector ‘policy community’ (Kendall, Reference Kendall and Kendall2009). This is taken to encompass both third sector representative organisations (variously known as umbrella, intermediary or infrastructure bodies); academic, consultant, think tank and specialist state actors who have been closely involved in the design and/or evaluation of policy; and the specialist media, such as the ‘trade journals’ for these organisations. Selection of potential interviewees was based on the need to include perspectives from key national infrastructure bodies and also from those possessing expertise on key aspects of activity associated with the third sector. Twelve interviews were conducted in June and July 2015; the majority were face-to-face with a small number by telephone. Interviews covered several topics, including: personnel; finances; legal and organisational formats; governance; image; sectoral infrastructure; equipment; and inter-sectoral and inter-organisational cooperation. Two national stakeholder meetings took place in July 2014 (focusing on impacts of the third sector and influence of the policy environment) and in February 2016 (focusing on project findings and barriers and constraints facing the third sector). For more detail, see http://thirdsectorimpact.eu/documentation/tsi-barriers-briefing-no-1-english-third-sector-policy-in-2015/

In section 4, we complement these perspectives with extensive quantitative results from a survey undertaken in 2015. This research attempts to gauge the ‘barriers and opportunities’ encountered by third sector organisations in their efforts to make social, political and economic impacts. A database on the distribution of registered charities, generated by the Charity Commission, included contact information for 128,582 organisations was our empirical entry point. We focused upon those operating in England in five core social policy fields, as described above. This gave just over 55,000 organisations for our sample population. An invitation email with a link to the questionnaire was automatically generated and sent, followed up by a reminder. The survey was conducted during July-August 2015 and achieved 1,182 useable responses, with 1,089 ultimately included in our reported data after excluding charities with incomes greater than £1m (few responses were received from such organisations). We considered over 40 potentially inhibiting factors to the realisation of third sector impact, under the thematic headings of: finance; human resources; governance; image; facilities; external relations; legal and institutional environment; and infrastructure. The generic survey instrumentation was tailored specifically to give us much more explicit traction in relation to dimensions articulated in this paper (e.g. references to the ‘Big Society’).

Independent variables, as well as the ICNPO classification, included the age of the organisation (defined in terms of the number of years on the Charity Commission register; since the Register has been in operation since 1961 we can make comparisons between organisations of widely-differing longevity, over a period spanning more than half a century); income; geographical location (region); scale of operation (generated through the process of registration with the Commission (charities state whether they operate within one local authority, across a number (2 – 10) of authorities, or on a national or international basis); and the level of deprivation in the immediate locality in which the charity was based (measured using the Index of Material Deprivation, a composite and widely-used indicator of relative disadvantage (2010: the latest version available at the time the analysis was carried out). These allow us to explore whether variations in responses to survey questions are systematically related to background characteristics of the organisation. The characteristics of the respondents are compared with those of the charity population as a whole in Table 1 (the full questionnaire is available in online material as Appendix A).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics: survey respondents and the population of social policy charities

There are some limitations associated with the survey data. One obvious question concerns the representativeness of the respondents in a survey in which the response rate was low (c. 1100 responses from a survey initially sent to over 50, 000 charities). In particular as noted above, we received few responses from very large organisations and dropped these from the analysis as a result. We address this in Appendix B (online material) which considers differences between the characteristics of those organisations who responded to the survey and those of the charity population more generally, and describes our response to this. We re-weighted the responses to adjust for differences in the size and subsectoral distribution of our respondents, compared to the charity population as a whole.

We are unable to adjust for any systematic differences in relation to the outcome variables in question. For example, one might postulate that, given the focus of the questionnaire on barriers to the operation of voluntary organisations, including the availability of public funding, we would receive disproportionately more responses from entities that depended on such sources. However, such data are not available, especially for small- and medium-sized organisations, and we therefore accept that it is possible we have been unable to adjust for all such sources of error.

There is also the question of the timing of the survey, which was conducted at a time of austerity policies, but we have no comparable data on previous periods of fiscal retrenchment and therefore it could be argued that we are unable to detect genuine effects of austerity. We cannot rule out the possibility that we would have had a similar pattern of responses had the survey taken place outside a period of austerity.

3. Expert policy community perspectives

In order to bridge the conceptual abstractions introduced in section 1 and the quantifications presented in section 4, we here summarise relevant ‘expert’ perspectives and insights, gleaned from long-standing and deeply experienced members of the third sector horizontal ‘policy community’ at the English national level (Kendall, Reference Kendall and Kendall2009; “horizontal” here means “cross-cutting”, whereby the policy actors in focus hold expertise in relation to issues relating to the sector as a whole, rather than confined to specific policy subfields).

In relation to volunteering, the evidence from survey data relating to individuals suggests stability. Thus, while volunteering levels had not surged in the way that the architects of the ‘Big Society’ agenda would have hoped to facilitate substitution for ‘Big Government’, at least austerity-related pressures had not lead to contraction. Our experts tended to believe that formal volunteering (i.e. activity that takes place through an organisational structure, rather than offers of help directly to individuals) had proven more durable than informal volunteering, which had been significantly undermined by ‘social recession’ (see Lim and Lawrence, Reference Lim and Laurence2015, for confirmatory evidence). But at the same time, because austerity policy implementation has lead to the rapid extension and intensification of unmet social need as the State withdrew, it could be concluded that, in relative terms, the situation had deteriorated: a significant shortfall had opened up at the national level. In contrast, the paid employment situation may have proven more responsive, at least in the short term (see Birtwistle and O'Brian, Reference Birtwistle and O'Brian2015).

A range of concerns was associated with this perception of volunteering insufficiency. The first connected with the perverse effects of the ‘Big Society’ discourse. Superficially, this orientation in public policy appeared attractive. But the realities of austerity policy resource constraints undermined this, as a matter both of ideology and implementation. In particular, the concept, at a philosophical level, was never clearly articulated and the connections between the Big Society and volunteering itself were never properly specified (House of Commons Public Administration Committee, 2011; Ishkanian and Szreter, Reference Ishkanian and Szreter2012). It was believed that this opacity could create suspicion, with potential volunteers demotivated for fear of being complicit with a political agenda to which they did not subscribe. The agenda in question involved assumptions that, through volunteering, people would be helping to deliver welfare ‘on the cheap’, letting the State ‘off the hook’ in relation to public responsibilities (see also Lindsey and Mohan, 2018: chapter 8)

Our respondents diagnosed a number of policy implementation difficulties regarding volunteers in general, in terms of specialist ‘infrastructure’ bodies (like volunteer bureaux and councils for voluntary service) but also organisations deploying volunteers much more generally. They also perceived an increasingly unstable situation linked to wider patterns of economic and intergenerational change (see Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Mohan, Brookes and Yoon2017 for a summary of these connections). Finally, one particular volunteer role – in governance terms, that of trustees – was also recognised as a key consideration. It was claimed that organisations were often struggling with trustee recruitment, retention and support. This was thought to be partly a reflection of the general pressures discussed above but also due to the demands associated with this particular, high-level responsibility. A range of technical/legal, social and political bodies of know-how and skills were believed to be required to discharge the role effectively. But with financial and time budgets under pressure, these could be increasingly hard to develop and apply. Two particular aspects of insufficiency were emphasised: the extent to which significant numbers of trustees simply ‘didn't understand what they were meant to do’ from a legal and regulatory aspect; and the sense in which relatively few had either the means or the mentality to focus appropriately on the outcomes and impacts of their organisation's activities.

We now consider the character of the policy environment including its symbolic character, as understood by our research subjects. Unsurprisingly, the overall sentiment regarding the ongoing direction of policy change at the time of our fieldwork (2015) connected closely with the issues and evidence circulating in policy circles at the time of our enquiry. Several of our interviewees had been involved in ‘unofficial’ foundation-funded initiatives (neither funded, not formally responded to, by the Government), and we need to recognise the focus of these reviews as a key frame of reference for our research subjects. The picture painted by these independent reports occupied a mixed middle ground between the optimism of the NCVO-led formulations and the pessimism of the ‘rejectionist’ critics, as identified in section 1. A leading orchestrating and narrative-designing role had fallen to a relatively new think tank, Civil Exchange, involving three ‘Big Society’ assessments and five reports from a panel on the independence of the voluntary sector (Slocock et al., Reference Slocock, Hayes and Harker2015; Slocock with Davies, Reference Slocock and Davies2016). This series of reports, while deploying appropriate quantitative indicators, also drew on ‘softer’ evidence as well and strove to make qualitative judgements concerning the ‘climate’ for, and situation of, the voluntary sector in policy terms. The analysis was developed against the backdrop of an assumption that the ‘independence’ of the voluntary sector in terms of ‘purpose, voice and action’ was essential for the sake of the health of democracy; and that the claims of the ‘Big Society’ agenda were, in principle, worth testing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Baring/Civil Exchange report themes

In developing this agenda, the Independence Panel uses one very evocative formulation: the threat to ‘voice’. This was, at the time, said to be exemplified by:

• the emergence of so-called ‘gagging clauses’ in some State contracts;

• the potential negative effects of other emerging legislation (in particular, pending Lobbying Act provisions);

• the de novo requirement that, specifically for central government programmes, funding should not be used to support lobbying;

• rhetorical statements suggesting charities should ‘stick to their knitting’ by both a regulatory institution (Charity Commission) board member and the (then) Civil Society Minister.

Taken together, this language and the associated institutional developments were said to constitute a ‘negative climate’, with potential for ‘self-censorship’ (see also Morris, Reference Morris2015, on ‘chilling effects’). These focal points for policy concern clearly exhibit a collective belief in the salience of what we referred to in the introduction as symbolic/climatic dimensions of the policy environment, and the potential links between austerity policies, identity and capacities to pursue and balance multi-functionality. They also suggest the relevance of recognising the leading regulatory and discursive significance of the State, in addition to its funding role.

In the body of its fifth report, the Independence Panel had gone so far as to refer to the overall situation as one of ‘potential crisis’ (Slocock with Davies, Reference Slocock and Davies2016: 9). The themes emerging from our expert interviews fitted closely with this agenda, but with varied emphases, and with one additional element: mediatization. We here briefly consider finance, the non-financial environment and media aspects in turn (see Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Mohan, Brookes and Yoon2017, for more discussion). In relation to the financial situation, on balance most of this policy community did tend towards a ‘potential crisis’ interpretation, making strong claims concerning the overall impact for social policy charities. Language such as ‘chronic financial insecurity’, ‘massive, massive change’, ‘draconian cuts’, being ‘hammered’ and ‘being screwed’ was articulated, while referring to the ‘collapse’ of key public funding streams. This was within subfields including community development and social care, but also in relation to specific forms of finance and, in particular, funding for ‘grants’ and ‘infrastructure’. While other sources of finance, including individual giving, were acknowledged to be more resilient, it was thought to be ‘getting harder’ to raise funds elsewhere. This issue was connected by interviewees to austerity pressures on household incomes, but was understood by several to be linked also to the build up of negative reporting in the mainstream media (see below).

Concerning non-financial dimensions of the policy environment, a rather more varied picture emerged: there was a wider spectrum or range of sentiments, perhaps best portrayed overall as manifesting ‘considered concern’ rather than ‘potential crisis’. In relation to regulation, there was serious discomfort in evidence concerning some aspects of the Charity Commission's direction of travel, including its budgetary contraction, and the perceived shift towards a more combative style of leadership (see Morgan, Reference Morgan2015). But its overall legitimacy as regulator was not brought into question, and some welcomed aspects of its ‘tougher’ approach. Likewise, in relation to impressions of the overall ‘climate’, there were different degrees of concern. This was partly because some of the evidence concerning ‘threats to voice’ posed by Government was thought to be particularistic and not easy to generalise across the entire sector, and partly because some of the implicated policy measures were, in 2015, still in the process of development, with uncertain trajectories.

Adding to the picture of the co-existence of a diversity in interpretations, once issues beyond direct finance were considered, was thinking about the media. It was agreed that high-profile, controversialist and critical attention to voluntary sector issues in national newspapers was now an additional ingredient beyond the State in generating the ‘climate’. So the issue had heightened salience. But there was as yet no consensus on how this converted into substantive long-term implications for the voluntary sector with different views arranged along a spectrum from those who suspected durable damage was being done to public image at one end, to those who believed any negative effects to be essentially transitory irritants.

4. Quantification of volunteering and ‘climatic’ effects: survey evidence

As section 2 outlined, we also undertook an online survey, drawing a response from just over 1,000 English social policy charities. Of course any such study could be dismissed on the grounds that respondents would tend to indulge in special pleading and be motivated by a self-interested desire to gain resources. In contrast, because we believe these organisations tend to be significantly oriented to the public good, and possess a great deal of relevant experience and expertise, we take respondents’ needs-related claims and beliefs to be potentially both credible and well informed. Moreover, we have seen that, by comparing the characteristics of our sample respondents with administrative data holdings, our sample was broadly representative of the national picture (see Table 1, and Appendix B online). In terms of the framing of our instrumentation, following the overall formulation of the European research study of which this was part, the survey asked respondents about a range of relevant perspectives under the overall banner of ‘barriers to realising impact’, expressed as both internal and external limiting factors. However, to link this firmly to the context of austerity, we adapted the specific questions with particular reference to subjective beliefs about trends in the UK policy environment over the preceding five-year period. (Bearing in mind that the Coalition government primarily associated with austerity policies in 2015 had won political office in 2010).

What were our key results in terms of descriptive findings (see Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Mohan and Brookes2015, for a more general overview)? First, although in excess of 40 potential limiting factors were posited (based on the pan-European research approach), just three of these dominated the responses: shortfalls in relation to volunteering; perceived financial shortfalls; and limits to public awareness of the responding organisations. Significantly, concerns about volunteering recruitment were the most prevalent of all factors. 51 per cent of respondents indicating that ‘trustee recruitment to Board’ was a serious or very serious issue, and 47 per cent indicating that ‘volunteer recruitment (other than trustees)’ was serious too. These concerns even outdistanced the most pervasive financial issue cited – the problem of local government funding, in relation to which 45 per cent specified a perceived shortfall. ‘Limited public awareness’ was invoked by 44 per cent and ‘Trust / foundation funding shortfalls’ by 43 per cent. All other categories of shortfall or barrier accounted for well below 40 per cent of responses.

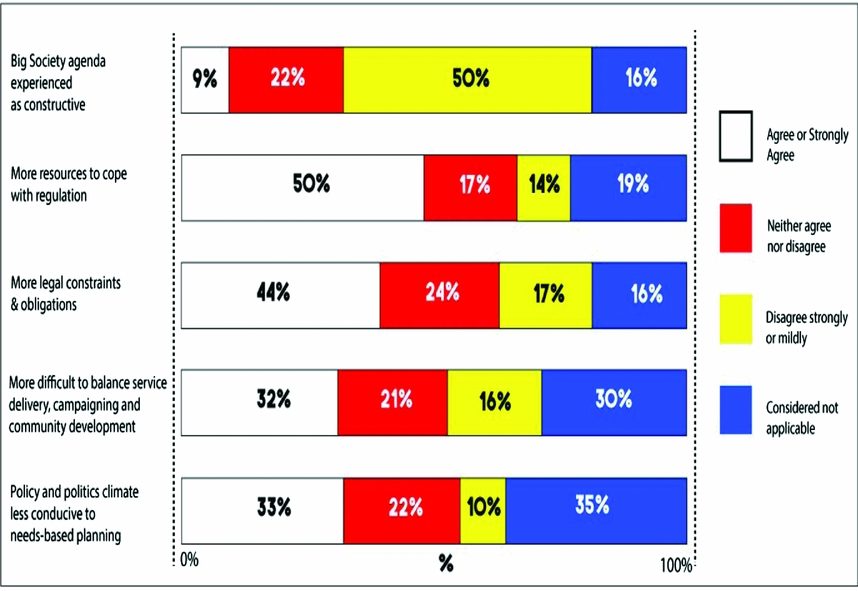

Second, in the later parts of the questionnaire, respondents expressed their beliefs about what we have formulated here as a range of ‘climatic’ aspects of the context for their activities. There was evidence of significant perceptions of intensification of competitive processes in relation to fundraising and market-style relationships and practices although, in relation to the latter, even more respondents actually indicated that they were ‘not applicable’. It is important, therefore, to recognise that the reach of market-style processes into this sector should not be overstated. But certainly the most striking single finding from this element of the survey was the pervasiveness of negative sentiments revealed in relation to the ‘Big Society’ construct: only a small minority (10 per cent) experienced this agenda as ‘constructive’, while five times as many (50 per cent) disagreed. Also, the legal and regulatory aspect of organisational life was quite widely perceived to have become more onerous since 2010. On a more modest scale, but still quite extensive, were concerns about respondents’ ability to balance their roles and functions (including those associated with ‘voice’) and the extent to which needs-based planning had become more difficult during the five-year period. Figure 2 presents these descriptive results in relation to these aspects.

Figure 2. Perceptions of five year continuity and change

The next step we took was to investigate the extent to which these key austerity policy-related perceptions and beliefs were systematically related to the characteristics of organisations and their geographical positioning. Conscious of the internal diversity of the sector (Kendall and Knapp, Reference Kendall and Knapp1996; Clifford and Mohan, Reference Clifford and Mohan2016), and of a range of literature highlighting spatial variation and links between economic activity and geographically defined deprivation indices (Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Geyne Rajme and Mohan2013; Mohan and Breeze, 2016), we wished to establish the extent to which our non-financial subjective data also manifested related patterns.

We developed logistic regression models to explore these relationships statistically. First, we looked at a key ‘non-resource input’ indicator – perceptions of volunteering shortfall – as our explanandum, collapsing the range of responses in three respects – (a) recruiting volunteers; (b) retaining trustees; and (c) recruiting trustees – into dichotomised dependent variables (strong or mild agreement that there were recruitment difficulties, versus all other responses). We then look at three measures of ‘impact on organisation's performance due to the climate of policy and politics’, again dichotomised. The choice of indicators here was prioritised by both the conceptual and qualitative considerations set out in the introduction, and the descriptive results in the survey itself. We considered organisations’ perceptions of (a) the extent of difficulty in balancing multiple objectives of service delivery as well as campaigning and community development; (b) impact of the policy climate on their ability to execute needs-based planning; (c) perception of the extent to which the ‘Big Society’ approach had helped organisations develop in the post-2010 period.

The models themselves are presented in Tables 2 and 3, and here we emphasise two overarching points. First, regarding volunteering, there were only generally weak links between policy field, age of organisation and extent of deprivation in the respondent's geographical home base. In terms of volunteers (other than trustees), organisations operating in the health field were statistically less likely to perceive difficulties in recruiting volunteers than those in other fields. However, with regard to trusteeship, organisations registered since austerity policies began to be applied in earnest (2010) and those situated in levels of deprivation in the 3rd and 4th quintile (with reference to the 1st quintile as the least deprived) perceived their problems to be worse. The point about youthful organisations experiencing difficulties might reflect the ‘liability of newness’ (Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe and March1965) – namely that newly-formed organisations take some time to acquire resources and develop networks on which they can draw (in this case, for trustee recruitment). However, if this were a significant problem for recently-established organisations, one would also expect it to affect other issues considered in this article but we find no consistent relationship between age of organisation and the likelihood of particular responses to the survey (other than in relation to comments about balancing service delivery and campaigning, for organisations established in the 1990s and 2000s). As to the recruitment of trustees in areas of deprivation, the suggestion that the trustee retention problem is apparently not also reproduced in the 5th (poorest) quintile is puzzling; given spatial disparities in volunteering between communities one might expect a gradient to be evident. But perhaps the most striking overall result from the volunteer shortfall perception model is the extent to which clearer, more decisive differentials don't emerge in these relationships. Against the backdrop of the relatively high frequency of volunteer/trustee problems revealed in our descriptive summary, the best way to read these results may be as indicating the pervasiveness of the volunteer/trustee problem across the sector as a whole, in spite of its internal diversity.

Table 2. Third Sector organisations perceiving difficulties relating to non-financial resources: results from a series of logistic regression models (odds ratios) with 95% confidence interval

Note: *** p < 0.001, ** p <0.01, p*<0.05; odds ratios from logistic regression on subjective non-financial difficulty measures.

Table 3. Third sector organisations perceiving difficulties regarding operating environment: results from a series of logistic regression models (odds ratio) with 95% confidence interval

Note: *** p<0.001, ** p <0.01, p*<0.05; odds ratios from logistic regression on subjective non-financial difficulty measures.

Second, our models of ‘climatic’ effects generated rather more clearly differentiated patterns. In one crucial respect, the results match quite closely with established findings about the link between traditional third sector economic indicators and geographically based deprivation measures (Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Geyne Rajme and Mohan2013; Mohan and Breeze, 2016): our data shows that organisations situated in the 20 per cent most disadvantaged locations were especially likely to have found balancing their functions and objectives more difficult since 2010; to have experienced the political environment as increasingly unsupportive for needs-based planning over the period; and also to disagree that the ‘Big Society’ agenda has been constructive. The analysis also shows that the one organisational characteristic systematically linked to both perceived capacity to balance multiple functions and to needs-based planning in the current policy climate is financial scale. Organisations with relatively small budgets (below £100,000) were significantly less likely to express an unfavourable view on the climate of politics and policy than the larger ones during the austerity period. In addition to size measured in financial terms, organisations operating in more than one local authority were significantly more likely to express unfavourable views on their ability to balance competing objectives, and conduct needs-based planning, compared both to locally-focused entities, and to the base category of organisations operating at least at the national scale. Needs-based planning was also perceived as a troubling issue by organisations operating within one local authority.

More research is needed to understand this pattern, but we speculate it may be linked to the higher levels of complexity that larger organisations face, combined with a possible tendency to be feel more ‘connected’ to and be more sensitive to issues framed in relation to national policy developments and the evolving agendas of central government. This in turn potentially generates feelings of great ‘exposure’ to the associated perceived negative effects when austerity policies are enacted. In relation to the challenge of balancing functions being associated more with larger organisations, respondents may be more sensitised to this challenge if it ties in with their formal organisational structure; bigger organisations are much more likely to have separate divisions, departments, units or groups of staff specialising along these lines (see Frumkin, Reference Frumkin2005; Anheier, Reference Anheier2014). By contrast, in smaller agencies, functions may generally be undifferentiated and either shared loosely by individual paid staff and/or volunteers (reflecting ‘ambiguities’, as per Billis and Glennerster, Reference Billis and Glennerster1998); or even be undertaken on a taken-for-granted basis, without reflecting on the extent of their manifestation.

5. Conclusion

The financial dimension of organisational life is clearly crucial to all voluntary agencies and, understandably, much debate has focused on the extent of fiscal and recessionary constraint on their budgets. That said, we have argued here that it is not sufficient to focus upon financial inputs when seeking to understand the situation of third sector organisations. The position of volunteers, upon whom these organisations rely, not least for reasons of governance, must also be considered. It is also important to attend to these organisations’ subjective beliefs about the nature of the sector ‘climate’ that they are experiencing, and the ways in which it is believed to be linked to their capacities to flourish or otherwise. We have sought to develop these ideas conceptually, and to present empirical evidence in support of them. Some but not all of the evidence that we have deployed has been quantitative in character, seeking to advance our ability to capture what are often regarded as essentially qualitative phenomena in quantitative terms. In a world in which there may be a tendency to only ‘treasure what we measure’ (Bache and Reardon, Reference Bache and Reardon2016) this seems to be advisable.

In terms of the specific debate concerning the trajectory of the voluntary sector against the backdrop of the UK's austerity social policies, we hope this type of approach can broaden the quantitative representations that have dominated in recent years, and also help complement and contextualise ongoing case study work at the local level. With regard to the stylised views on the situation identified at the start of the paper, we believe our findings provide grounds for neither a uniformly optimistic nor pessimistic approach, but resonate with many of the concerns tabled by the Civil Exchange think-tank. However, they also suggest that critical narrative should itself become more focused on the centrality of volunteerism for the voluntary sector and, when it comes to climatic experiences, be more sensitive to internal differentials, including those associated with different degrees of role specialisation.

In general, our models also imply that a range of qualifications, contingencies and cautionary notes may be needed to connect the ‘typical’ perspectives and experiences of charities themselves with the national narratives as they currently stand. Since we conducted our fieldwork, there have been encouraging signs that, in relation to volunteering, and especially trusteeship, increased recognition of the existence of a significant problem has grown. This is a positive step, even if it may have been driven more by short term adverse mediatization effects, including the fallout from the recent Kids Company scandal, than by longer term research-based learning (House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2016; Brindle, Reference Brindle2017; House of Lords Select Committee on Charities, 2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Harris, Stickland and Pesenti2017). But in relation to the adverse effects of austerity and related policies on the ‘climate’ that these organisations inhabit, apart from quietly distancing itself from explicit ‘Big Society’ rhetoric by referring instead to a ‘Shared Society’, the current Conservative Government has expressed no systematic desire to come to terms with the dangers posed by the current situation. This must be seen as a matter of real and ongoing concern for all those who treasure the sector's diverse contributions to the development of social policy.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of the EU 7th Framework Programme is gratefully acknowledged: grant agreement 613034, Third Sector Impact project, co-directed by Bernard Enjolras, Institute for Social Research, Oslo, Lester Salamon, Centre for Civil Society Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Annette Zimmer, University of Muenster, Muenster, see http://thirdsectorimpact.eu/. John Mohan and Yeosun Yoon are also grateful for the financial support of ESRC (Grant ref: ES/N005724/1).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000107