Introduction

As economic inequality grows in many countries throughout the globe, everyday observers and scholars have predicted that the poor and middle class will demand more redistribution (Meltzer and Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981; Franko et al., Reference Franko, Tolbert and Witko2013; Noureddine and Gravelle, Reference Noureddine and Gravelle2021). More generally, scholars have puzzled over why the poor and middle class do not extract more resources from the rich in democracies, where they potentially have the votes to elect majorities and shape policy (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2002; Dallinger, Reference Dallinger2013). Here, we examine how attitudes toward government and the targets of redistributive policies relate to support for redistribution in countries transitioning from communism, admittedly at varying trajectories, which as a group have been examined much less frequently than affluent, advanced democracies.

Many models of attitudes toward redistributive policies begin with the assumption that individuals will view redistribution through the lens of economic self-interest, leading to the expectation that the poor will prefer redistribution, while the rich will be opposed. Some research certainly supports this expectation (Boudreau and MacKenzie, Reference Boudreau and MacKenzie2018; Franko and Witko, Reference Franko and Witko2018; Newman and Teten, Reference Newman and Teten2021). Yet, broader factors beyond self-interest may also shape preferences for redistribution alongside economic self-interest (Dallinger, Reference Dallinger2013; León, Reference León2012; Vaalavuo, Reference Vaalavuo2013; Franko, Tolbert and Witko, Reference Franko, Tolbert and Witko2013; Jacques and Noël, Reference Jacques and Noël2018; Bobzien, Reference Bobzien2020; Noureddine and Gravelle, Reference Noureddine and Gravelle2021). Though, at times, governments may redistribute income even in the absence of public support, or at the other extreme, governments may refuse to do so against the public’s will (Kenworthy and McCall, Reference Kenworthy and McCall2008), democratic theory suggests that redistribution is more likely if the public calls for it. Thus, it is important to understand what factors shape public attitudes toward redistribution, especially in the current context of growing economic inequality in many countries.

Two different streams of research have examined how attitudes toward the government, as well as the rich and poor, shape support for redistributive policies. In the first stream, studies suggest that negative attitudes toward government can inhibit support for redistribution (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005; Rudolph and Evans, Reference Rudolph and Evans2005; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2009; Tuxhorn et al., Reference Tuxhorn, D’Attoma and Steinmo2019; Garritzmann et al., Reference Garritzmann, Neimanns and Busemeyer2021). If people do not have confidence that the government will do the right thing, they will have less expectation that redistribution will be carried out fairly or effectively. Scholars have examined how perceptions of corruption (used as a proxy for trust in Peyton, Reference Peyton2020) may shape attitudes toward redistribution. While there has been less research into corruption and support for redistribution, it seems intuitive that a belief that one’s government is corrupt would lessen individual willingness to endow it with more resources.

In the second stream, scholars have considered how attitudes toward the targets of redistributive policies shape support for redistribution. Redistribution generally targets the wealthy with progressive tax increases to provide general services, including income transfers for the poor. Research shows that attitudes toward the rich and poor can powerfully shape public support for policies that directly impact these groups (Laenen, Reference Laenen2020; Piston, Reference Piston2018). Indeed, in actual political debates about redistribution, the relative weight given to negative attitudes toward the wealthy and sympathy toward the poor, as well as negative attitudes toward the government can determine whether policies are enacted (Barton and Piston, Reference Barton and Piston2021).

Attitudes Toward Government, Rich and Poor

As noted, classic models of redistributive policies assume that self-interest will lead poor and middle-class individuals to prefer redistribution. Several studies offer empirical evidence that the poor or lower income households prefer more redistribution (Franko et al., Reference Franko, Tolbert and Witko2013; Kevins et al., Reference Kevins, Horn, Jensen and van Kersbergen2019; Newman and Teten, Reference Newman and Teten2021). But research also shows that many individuals are ignorant of their place along the income distribution ladder (Gimpelson and Treisman, Reference Gimpelson and Treisman2018) and have a much greater confidence in their ability to earn higher incomes, which suppress demands for redistribution (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Stantcheva and Teso2018; Cojocaru, Reference Cojocaru2014). Thus, even as many studies evaluate the link between economic self-interest and redistributive preferences–regardless of whether incomes are objectively or subjectively defined–, they find that broader political attitudes are equally important for individual support of redistributive policies (Castles and Obinger, Reference Castles and Obinger2007; Franko et al., Reference Franko, Tolbert and Witko2013; Kevins et al., Reference Kevins, Horn, Jensen and van Kersbergen2019; Bobzien, Reference Bobzien2020; Noureddine and Gravelle, Reference Noureddine and Gravelle2021; Sumino, Reference Sumino2014; Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Jones and McBeth2011).

Attitudes Toward Government

Even if individuals believe that redistribution in the abstract is a good idea, they might not support it in practice. This can happen if they have negative beliefs about the government’s intention or ability to carry out an effective redistributive program. While surveys rarely ask respondents whether they think that their government can deliver on plans to redistribute income, several scholars have argued that trust in government leads to greater support for government policies in general (Bergman, Reference Bergman2002; Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005; Lim and Moon, Reference Lim and Moon2022; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2009) and taxing and spending policies specifically (Tuxhorn et al., Reference Tuxhorn, D’Attoma and Steinmo2019; Garritzmann et al., Reference Garritzmann, Neimanns and Busemeyer2021). Trust in government is seldom clearly defined, however, and this is partly because it is a multifaceted construct spanning levels of government, varieties of institutions and types of actors within the government (see Gilson, Reference Gilson2003 and Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Ward, Coveney and Rogers2008). Other scholars have used low trust in government interchangeably with public cynicism toward government institutions and actors (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose1997; Peterson and Wrighton, Reference Peterson and Wrighton1998). But, as we are focused more on governing institutions broadly defined, for our purposes it refers to the belief that various institutions and actors in the government will generally ‘do what is right’, even in the absence of public scrutiny (Miller and Listhaug, Reference Miller and Listhaug1990).

Trust in government can matter because the outcomes of public policies are often uncertain and risky (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2009). If people trust their government, they will take a leap of faith and support government policies, all else equal (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005; Garritzmann et al., Reference Garritzmann, Neimanns and Busemeyer2021). In the case of redistribution, as governments make claims about the costs and benefits of public policies, individuals who trust their government institutions and actors will be more likely to accept these claims at face value. Research shows that redistributive policies that require taxing (the middle or high income) and spending (on the poor) depend on such trust. For instance, Rudolph (Reference Rudolph2009) finds that liberals who trust the government in the U.S. are more likely to support tax cuts (which they would otherwise oppose), whereas Tuxhorn et al. (Reference Tuxhorn, D’Attoma and Steinmo2019) report that both liberals and conservatives in the U.S. who trust their government have overlapping, even converging spending preferences. In an experimental study, Kuziemko et al. (Reference Kuziemko, Norton, Saez and Stantcheva2015) established that information treatments do not affect individual preferences for redistribution if low trust in government institutions or actors is present.

However, not all studies find support for these arguments about trust in government. In another experimental study, Peyton (Reference Peyton2020) finds that individuals exposed to information about government corruption (intended to reduce trust) in the U.S demonstrate little difference in support for redistribution (food stamps, welfare, programs that assist ‘blacks and other minorities’, and assistance to the homeless) compared to their control group. Though this study is extremely creative and overcomes challenges of observational research (i.e. omitted variable bias and endogeneity between policy attitudes and trust), there are questions about whether this experimental treatment would be comparable to actual experiences with corruption, as the author notes.

One of those omitted factors that may limit the potentiality of governments to redistribute income is public sector corruption. Corruption is closely related in the literature to trust in government institutions and actors. Indeed, while studies show that perceptions about corruption shape public trust in government (Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003), others use the two terms synonymously (Peyton, Reference Peyton2020). Yet, trust and perceptions of corruption conceptually (and, as we will show, empirically) are distinct. While it is hard to imagine that a person believing that their government is corrupt will have a high level of trust in government institutions, it is relatively easy to imagine a person thinking that there is little public corruption, but still lacking trust in their government. Indeed, countries with objectively low levels of public corruption by international standards may still have many individuals with low levels of trust in government.Footnote 1

While lack of trust in government is quite generalized in terms of whether the institutions or actors will follow through with any given policy, corruption can deplete the resources intended to benefit the poor. Thus, it is reasonable for people to question whether redistribution would be carried out if their government were corrupt (e.g. Sánchez and Goda, Reference Sánchez and Goda2018; Olken, Reference Olken2006). Though there is less research on how perceptions of corruption affect support for redistributive policies, Bauhr and Charron (Reference Bauhr and Charron2020) find that individuals in countries with high levels of perceived corruption prefer that the EU play a larger role in redistribution rather than their respective national governments. As they put it “corruption can be highly detrimental for support for internal redistribution” (Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2020: 510).

Attitudes Toward Rich and Poor

The other key actors in redistributive policy debates, along from the median voters themselves, are the rich or affluent and the poor. The reason for their importance is not as simple as taking more from the rich to give to the poor. General attitudes toward the rich and the poor, or beliefs about how individuals become rich or poor, are also likely to matter for individual attitudes toward redistribution. For instance, countries often have divergent baseline attitudes toward the rich and the poor, potentially reflecting deeply ingrained discourses and beliefs about these groups. Compared to people in other affluent democracies, for instance, Americans tend to have relatively more negative attitudes toward the poor and view them as undeserving of government support (Aarøe and Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014). Yet, even within the U.S., there are those who have empathy toward the poor and view them as unconditionally deserving of redistributive programs (Kreitzer and Smith, Reference Kreitzer and Smith2018; Piston, Reference Piston2018; Schneider and Ingram, Reference Schneider and Ingram1993).

At the same time, antipathy toward the poor does not necessarily translate into widespread sympathy or support for the rich. The wealthy may be viewed by many individuals as not deserving of or needing government help (Kreitzer and Smith, Reference Kreitzer and Smith2018; Piston, Reference Piston2018). Moreover, Piston (Reference Piston2018) reports that when tax policies are viewed as benefiting the wealthy, they tend to receive less support from the public. On the other hand, Sznycer et al. (Reference Sznycer, Lopez Seal, Sell, Lim, Porat, Shalvi, Halperin, Cosmides and Tooby2017) find that those who have empathy toward the poor and who are more envious of the rich are more supportive of higher taxes on the wealthy. When studying motivations in Europe, León (Reference León2012:, 198) writes that “variables associated with ‘reciprocity’ are better predictors of support for the redistributive role of the State than those associated with ‘self-interest’’’.

Study Context

Most studies of redistributive preferences, and especially those that evaluate how attitudes toward government and attitudes toward the rich and the poor shape these preferences, have focused on affluent, long-established Western democracies (but see Cojocaru, Reference Cojocaru2014; Haggard et al., Reference Haggard, Kaufman and Long2013; Munro, Reference Munro2017). This is sensible given that many Western countries, especially the U.S., have experienced rapidly growing inequality in recent decades (Moldogaziev et al., Reference Moldogaziev, Monogan and Witko2018; Franko and Witko, Reference Franko and Witko2018; Choi and Neshkova, Reference Choi and Neshkova2019), such that their democratic systems should make it especially likely that politicians seek to redistribute income in response to public preferences.

Yet, inequality is a problem in many developing economies as well, including the transitional economies in our study, adding to a host of social problems they must handle (Fabian and Straussman, Reference Fabian and Straussman1994; Fajth, Reference Fajth1999; Lendvai, Reference Lendvai2008; Loveless, Reference Loveless2016). Almost all transitional countries in this study have seen extreme growth in economic inequality (e.g. the rise of the super-rich or the ‘oligarchs’ across the region), they have been plagued with public sector corruption, including those that are members of the EU, and continue to suffer from public cynicism toward government institutions (Moldogaziev and Liu, Reference Moldogaziev and Liu2021; Guriev and Rachinsky, Reference Guriev and Rachinsky2005). Regarding inequality, of the 22 countries in our sample (for which data are available between 1990 and 2016), 18 experienced an increase in their Gini coefficient, with an average increase of 7 points from the 1990 value (Solt, Reference Solt2019).

Key factors that contributed to inequality in this region are policies such as unscrupulous and haphazard approaches to privatization, loss of life savings and the collapse of social policy systems, and structural changes in welfare, labor market, and employment policies (Bandelj and Mahutga, Reference Bandelj and Mahutga2010; Milanovic, Reference Milanovic1999). Such extreme income inequalities should make the differences between the rich and the poor particularly salient in transition economies. Of course, the problems and solutions from post-Communist countries will be directly relevant for other contexts as well--certainly in countries with varying levels of trust in government and public corruption where poverty and social policy tools continue to be the most critical problems (e.g. Blore, Reference Blore1999).Footnote 2

Methods

Data and Sample

We use the Life in Transition Survey’s (LiTS) third round, which was administered in 2016. It surveyed approximately 1,500 people in each country for a total sample size of over 40,000. The LiTS was conducted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in 34 countries, consisting primarily of 29 countries transitioning from Communism.Footnote 3 We do not include Turkey, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, and Germany, because we are interested only in post-Communist countries. Due to missing data, the final models we estimate have a sample of approximately 23,000 respondents from transitional economies. However, we use multiple imputation to recover observations with missing data for robustness purposes and present these additional models in the Appendix, as we describe below.

The survey has several questions that tap into the outcomes of interest, which includes items that measure abstract preferences for reducing the income gap between the rich and the poor and a more specific individual willingness to pay more to help the needy. This is an important distinction--as individuals are forced to pay for something, they may often want less of it (Citrin Reference Citrin1979; Glaser and Denhardt, Reference Glaser and Denhardt1999), and in all countries, at least some people would need to pay higher taxes to reduce income disparities to desired levels.

Variables and Measurement

Preferences for Redistribution

Following Cojocaru (Reference Cojocaru2014), we use the question that asks people to agree or disagree with the following statement along a 5-point Likert scale: ‘The gap between the rich and the poor in our country should be reduced.’ Note that this question does not ask about who pays to reduce inequality, nor does it explicitly ask about the role of the government in reducing inequality.Footnote 4 The second question that measures preferences for redistribution asks, ‘would you be willing to give part of your income or pay more taxes, if you were sure that the extra money was used to help the needy?’ Respondents could have replied either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. This question queries people directly whether they personally would be willing to pay more for redistribution. Not surprisingly, more people report willingness to support redistribution (78.5%) if they don’t explicitly have to pay for it compared to when they do have to give up part of their incomes or pay more taxes (just under 58.6%).

For measurement consistency and comparability of our final empirical results for the two outcome variables, we dichotomize the response to the first question (regarding the gap between the rich and the poor) using the categories ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ as indicators of support for redistribution. As a robustness check, we present an ordered logit model for the five-choice categorical form of the variable in the Appendix in Table A2. The results for the explanatory variables from the robustness check model remain consistent with the reported binary outcome regression.Footnote 5

Trust in Government and Public Corruption

Our main explanatory variables measure whether individuals trust their government institutions and whether they perceive high levels of corruption in government. The LiTS asks ‘do you trust the following institutions?’ and lists several political, social, and economic institutions and actors. The levels of trust are measured on a Likert scale, which includes complete distrust, some distrust, neither trust nor distrust, some trust, and complete trust. Using responses regarding national-level government institutions (the presidency/prime minister, officials in their office, the government/cabinet ministers, and the Parliament), we created a scale that gives one point for each choice that the respondent has some trust or complete trust. The scale ranges from 1-4, where individuals with some trust or complete trust in each of the selected government institutions score a maximum of 4 points. The battery of trust questions is consistent with studies that have previously utilized numerous other public opinion surveys (Lühiste, Reference Lühiste2006; Lavallée et al., Reference Lavallée, Razafindrakoto and Roubaud2008).

To measure public corruption, we use a question asking: ‘how many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say?’. Answer choices are ‘none’, ‘some of them’, ‘most of them’ and ‘all of them.’ To keep the reference group focused on national policymakers, we construct a scale summing the items for national actors (i.e. the president/prime minister, officials in his/her office, members of Parliament, and government officials). We reverse the scores, so that higher values on this scale indicate perceptions of lower corruption. This will make the discussions of relative magnitudes and directions of association of trust in government and (the absence of) public corruption more sensible and direct. We again create a scale that gives one point for each actor that the individual selects ‘none of them’ or ‘some of them’ to be corrupt. Like the trust in government institutions measure, this scale ranges from 1 to 4, with 4 indicating the lowest level (or the absence) of perceived corruption. This survey item is again a common way to measure public sector corruption perceptions in other surveys (e.g. Wielders, Reference Wielders2013).

Other Attitudes Toward Government

We include a variable from the survey that asks: ‘in our country there is less corruption than four years ago.’ Responses range from strongly disagree to strongly agree on a 5-point scale. While this also taps into attitudes regarding corruption, it captures perceived levels of change in corruption levels in one’s country versus perceptions of overall current levels of corruption (the correlation between the two corruption measures is Pearson’s r = 0.16). We further control for a variable that asks individuals to rate the performance of their national government as either very bad, bad, neither good nor bad, good, or very good (1-5 scale). We also include variables measuring whether people agree that the economic and political situations in their country were better than four years ago (both on 1-5 scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree). Overall, since the measures of trust in government institutions, public corruption, and these other attitudes toward government exhibit correlation coefficients between 0.16 and 0.54, we conclude that while they are weakly to moderately correlated, all nevertheless remain conceptually and empirically distinct.

Attitudes Toward Rich and Poor

Our next set of main explanatory variables represent individual attitudes toward the rich and the poor. Though there are no questions in the survey directly asking people whether they are envious of or have other negative feelings toward the wealthy, there is a question that asks respondents to express agreement on a 10-point scale with one of the following statements: ‘There is no problem with the influence of wealthy individuals on the way government is run in this country’ versus ‘Wealthy individuals often use their influence on government for their own interests and there need to be stricter rules to prevent this.’ Higher scores indicate greater agreement with the second statement, and thus, indicate relatively greater levels of antipathy toward the wealthy.

Two questions are available in the survey to measure individual attitudes toward the poor. In the first one, we use the question that measures beliefs about whether the poor are worthy of government assistance. It reads ‘which of the following citizens deserve support from the government’ and lists several options including the ‘working poor.’ Responses that the working poor deserve government support are coded as 1 and 0 otherwise. For the second measure, we use individual attitudes toward various groups in a survey item that asks: ‘on this list are various groups of people. Could you please mention any that you would not like to have as neighbors?’ One of the response options in this item is ‘poor people.’ Unlike the first measure, which cues policy-relevant attitudes toward the poor, this question captures more generalized levels of orientation toward (living next to) the poor. The variables measuring attitudes toward the rich and the poor exhibit low levels of correlation, ranging from 0.01 to 0.09.

Remaining Controls

The survey allows for a rich set of controls, some of which are of substantive interest, that are likely to be associated with redistributive attitudes. We control whether individuals think that economic inequality in their country has increased with a question asking ‘do you think the gap between rich and poor in the past 4 years has stayed the same, become larger or become smaller in [respondent’s country]?’ If it is the case that perceptions, but not necessarily the reality of, growing inequality shape demand for redistribution (e.g. Franko and Witko, Reference Franko and Witko2018), individuals who think that inequality has increased should be willing to support redistributive policies.

Another variable of substantive interest is willingness to pay more for a range of public goods, which is something that studies examining preferences for redistribution seldom account for. Simply put, while some individuals not only support but also are willing to pay more for a variety of public goods (Alm et al., Reference Alm, McClelland and Schulze1992; Welch, Reference Welch1985; Jacques and Noël, Reference Jacques and Noël2018), others may be against sharing incomes or paying more taxes whatever the reason. The survey item we use asks about willingness to pay more to: ‘improve public education’, ‘improve the public health system’ and ‘combat climate change.’ We assign a point for each affirmative answer, such that the measure ranges from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher individual willingness levels to pay for public goods.

We further include the question that asks whether ‘Incomes should be made more equal’ versus ‘We need larger income differences as incentives for individual effort’, on a 10-point scale, where 10 is a strong preference for the second statement. However, we reverse-code this variable for ease and consistency of interpretations, such that 10 indicates greater agreement with the first statement. We also control for general attitudes toward private industry, which may be particularly salient in post-Communist countries. People are asked to select between two opposing statements using a 10-point scale whether ‘Private ownership of business and industry should be increased’ versus ‘Government ownership of business and industry should be increased.’

Finally, as existing research shows that individual characteristics matter for spending and willingness to pay levels (e.g. Kevins et al., Reference Kevins, Horn, Jensen and van Kersbergen2019; Simonsen and Robbins, Reference Simonsen and Robbins2003; Glaser and Denhardt, Reference Glaser and Denhardt1999; Donahue and Miller, Reference Donahue and Miller2006; Blekesaune, Reference Blekesaune2013; Anderson, Reference Anderson2017), we control for whether people think their household is doing better than four years ago. We also control for basic demographic factors including whether a respondent is female, an urban dweller, their age, perceived income position on a 10-point ‘income ladder’, whether they are poor or middle class, based on a question asking if their household could meet unexpected expenditures to repair dwelling, appliances, etc. with possible answers being ‘yes easily’, ‘yes with difficulty’ coded as middle class) and ‘no’, coded as poor)), and whether they are college educated. In Table 1, we present summary statistics for all the variables used in the study.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

Data Analysis

Because the two outcome variables are binary, constructed in a manner described above, and respondents are nested in 29 different countries, we use logistic multivariate regression models with country-level random intercepts. As we are only interested in individual-level attitudes, and we do not have a sufficiently large number of country units (Bryan and Jenkins, Reference Bryan and Jenkins2016), we do not include country-level variables in the main models but let the random intercepts account for the country-level heterogeneity. We do, however, present models with select country-level variables that may be associated with redistributive preferences in the Appendix.Footnote 6 Also, though our main explanatory variables are ordinal, we treat several of them as quasi-continuous and model them with a linear term rather than a set of binary categories. Doing so does not appear to change our main conclusions. Finally, as a fairly large number of observations have missing data on at least one variable, we present additional robustness models estimated using multiple imputation for missing values in the Appendix, where the regression results are consistent with the models presented in the main text.Footnote 7

Empirical Results

Comparable with earlier findings from transition countries (Ferge, Reference Ferge1997), we see that the share of people supporting the reduction of the income gap is 78.5 percent and those willing to pay more to help the needy is just under 58.6 percent. Interestingly, this is also comparable to abstract opinion polls exploring the same types of attitudes in Western nations. For instance, two-thirds of the public in the U.S. support increasing taxes on the wealthy to pay for government services.Footnote 8

The logistic multivariate regression analysis results are presented in Table 2. Results for the ‘reduce the income gap’ outcome variable are presented in the left column and for the ‘willingness to pay more for needy’ are found in the right column. Beginning with the former, trust in government institutions is found to be positively and significantly associated with support to reduce the income gap in one’s country. None of the other variables that measure attitudes toward government have significant coefficients, however. We further find that two of the three variables measuring attitudes toward the wealthy and the poor are significant in the expected direction. Thus, individuals who believe that the working poor are deserving of government support prefer the reduction of the income gap in their country, as do those who believe that the wealthy use the government for their own interests.

Table 2. Attitudes Toward Government, Rich and Poor, and Support for Redistribution

Ordered logistic regression coefficients with z scores in parentheses; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

In the latter column, individuals who believe that public corruption is not bad in their country appear to be willing to pay more for the needy. However, those who think that the situation with corruption in the country has improved in the last four years are found to be less willing to commit additional resources to support the needy. Since the question asking about changes in corruption levels does not explicitly mention the government, it may be drawing on attitudes about generalized corruption in society (e.g. bribing private employers to get jobs, for instance) rather than attitudes about corruption in the government. Alternatively, it is possible that the existing levels vs. changes in corruption are indeed differentially associated with willingness to pay more to help the needy. Further, we again observe that individual attitudes toward the rich and the poor are associated with willingness to pay more to support the needy. Those who believe that the poor are more deserving, are found to be willing to pay more to help the needy. We also observe that those who believe that the wealthy are using the government for their own interest are willing to pay more to help the needy.

Several control measures have coefficients in the expected direction and are statistically significant. Individuals who believe that the income gap has grown larger in their country in the last 4 years would like to see the income gap reduced, but it does not appear to be a significant predictor for willingness to pay more to help the needy. We also test for objective inequality for robustness purposes, measured at the country level for robustness purposes and presented in the Appendix. This coefficient is not statistically significant, however. Nevertheless, this finding is consistent with existing research showing that individual perceptions, but not necessarily objective levels of inequality, shape micro-level redistributive attitudes (Franko and Witko, Reference Franko and Witko2018).

General willingness to pay more for public goods appears to shape individual support for redistribution in all the regression models. Further, those who believe that income differences are needed to incentivize people to work more appear to be less supportive of the income gap reduction, while individuals who believe that incomes should be more equal in their country are found to be more supportive of reducing the income gap. Also, individuals who support more roles for private enterprise in their country appear to be against income redistribution. Further, people who report that their households are doing better than 4 years ago appear to support the income gap reduction and are willing to pay more to help the needy. Sensibly, people who place themselves higher on the income ladder appear to be less likely to support the income gap reduction in their country. Finally, older individuals are found to be more supportive of reducing the income gap in their country.

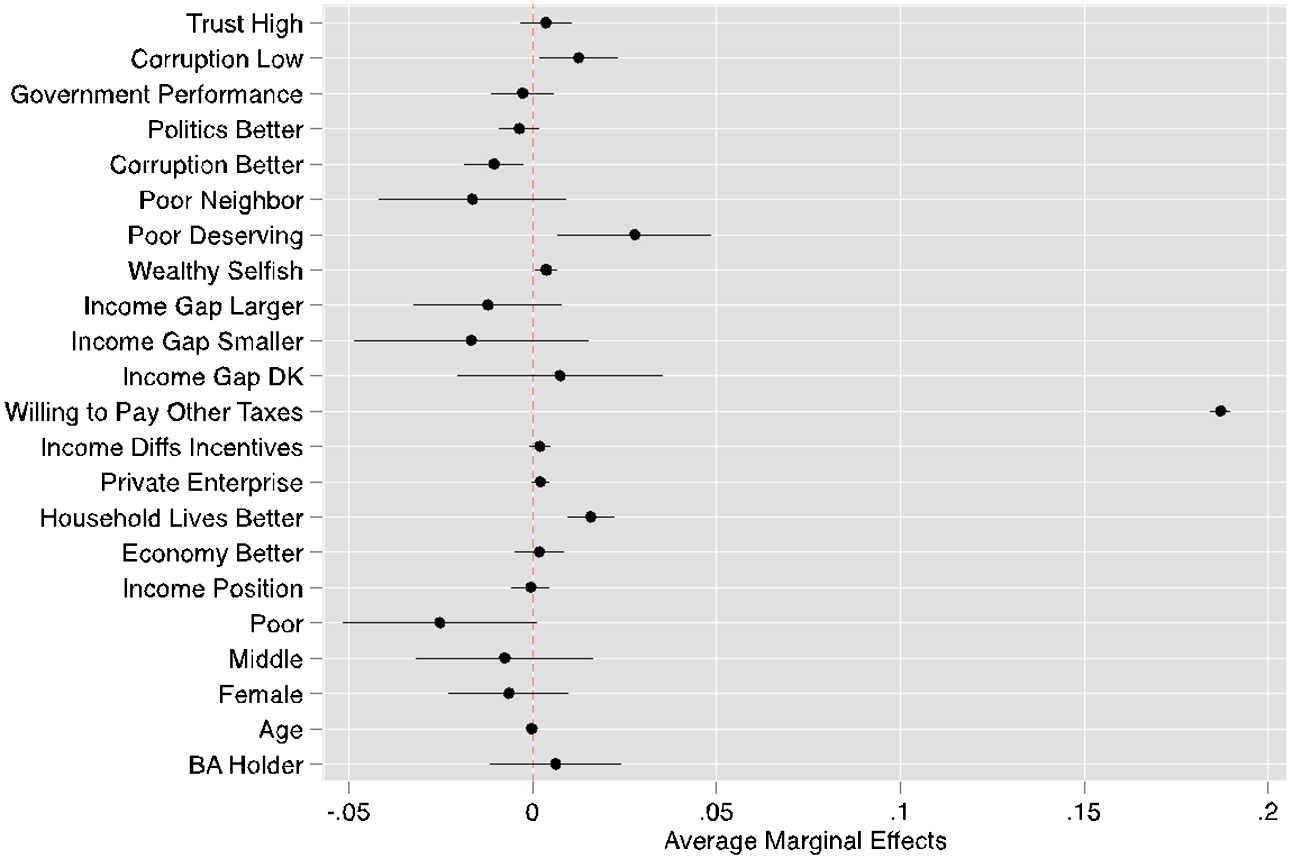

In Figure 1, we present the average marginal effects for the first, income gap reduction logit regression model. The average marginal effect represents the expected change in a probability of supporting the closure of income gap for a unit change in an explanatory variable, averaged across all respondents. Focusing on the main variables of interest, we find that trust in government has one of the larger marginal effects, with a one-unit change increasing the probability that a respondent will want to reduce the income gap by approximately 3%. Perceptions of the deservingness of the poor to receive government help have a similar, though a slightly larger marginal effect, with a one-unit change effect equaling to about 4%. Beliefs that the wealthy are selfish also appear to have a substantive marginal effect, with a one-unit change effect equaling a probability of 2%.

Figure 1. Average Marginal Effects, Reducing the Income Gap.

Next, in Figure 2 we present the marginal effects for the covariates in the willingness to pay more (commit more from personal incomes or pay additional taxes) to help the needy logit regression models. Here, of the main variables of interest, beliefs about deservingness of the poor are found to have the largest effect size (with a probability of approximately 3%). Perceptions that there is little corruption in government appear to increase individual willingness to pay more to help the needy by around 1%. However, beliefs that corruption has decreased in the country in the last 4 years are found to have the same effect size, but in the opposite direction. Further, believing that the wealthy are selfish and have too much influence in government, while significant, appears to have a relatively small marginal effect. Though not central in the study, by far the largest effect size is found for one’s general willingness to pay for public goods, where a one-unit effect is equal to approximately 18%.

Figure 2. Average Marginal Effects, Willing to Pay More for Needy.

In addition to the marginal effect plots, we present figures for the ways that variables relate to redistributive attitudes across a full range scale of the explanatory variables. These figures show predicted probability plots for the most theoretically and statistically significant explanatory variables as one traces them from the minimum to maximum values. We begin with the question regarding the income gap reduction in one’s country in Figure 3. In the top left panel, a minimum to maximum change in trust in government increases the probability of income gap reduction preferences by about 0.07. In the top right panel, a range increase in (the negative) feelings toward the wealthy has a substantive and significant relationship with support for income gap reduction, equalling to a probability of around 20 percentage points. In terms of the range effect of whether the poor are deserving to receive help, we see that a minimum to maximum change increases the probability of supporting the income gap reduction by about 0.04. A similar range change for believing that the income gap became larger in one’s country increases the probability of supporting the income gap reduction by about 0.07.

Figure 3. Predicted Probabilities for Reducing the Income Gap.

In Figure 4, we present analogous marginal effect plots for several covariates from the logit multivariate regression model for willingness to pay more (from personal incomes or additional taxes) to assist the needy. We observe that perceptions about corruption in government and beliefs that corruption in the country has decreased in the last 4 years have comparable levels of association (probabilities of 0.04), but in opposite directions. Further, a range change in beliefs that the wealthy are selfish in the use of government and that it needs to be prevented has a smaller association with willingness to pay more to help the needy (0.04) compared with support for the income gap reduction. Finally, a minimum to maximum level change for whether the poor are deserving of government help appears to result in an increase in willingness to pay more to help the needy by approximately 0.03.

Figure 4. Predicted Probabilities for Willing to Pay More for Needy.

Taking the regression results together, we conclude that both individual attitudes toward government institutions and attitudes toward the targets of redistributive policies are important covariates of redistribution policies in the 29 post-Communist countries we study. However, it appears that individual attitudes toward the rich and poor have relatively more consistent effects on preferences for redistribution compared to attitudes toward government. This is true in the model for individual levels of willingness to pay more to assist the needy and we observe the same association for the more generic ‘reduce the income gap’ question. We also find that beliefs regarding whether the wealthy are using the government for their own self-interest and the need to curb it are associated significantly with both outcome variables. These latter findings confirm empirical evidence in existing research from Western democracies, which shows that the perceptions of ‘deservingness’ of government benefits by certain groups as well as individual attitudes toward the rich and poor shape policy preferences in significant and substantive ways (Aarøe and Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Piston, Reference Piston2018).Footnote 9

Conclusions

Extant research has shown that negative attitudes toward government, especially lack of trust in government, can reduce support for redistribution (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2009) and that negative sentiments toward the targets of redistributive policies can also shape it in significant ways (Piston, Reference Piston2018). Individuals expressing antipathy toward the rich have been found to be more likely to support redistribution, while their antipathy toward the poor was likely to result in the opposite result (Piston, Reference Piston2018). Research regarding trust in government and attitudes toward the rich and poor has been conducted in Western nations, but post-Communist countries, some of which have successfully transitioned to become liberal democracies, contain populations that are largely disillusioned by their governments’ ability to address significant income inequalities. Our empirical results show that individual orientations toward the rich and poor are relatively more salient than attitudes toward government in these countries.

We also offer empirical evidence that both trust in government and perceptions of public corruption shape support levels for redistributive policies—with the former increasing the odds that an individual will support policies to close the income gap, and the latter increasing the odds of willingness to pay more to assist the needy. However, these variables are not consistently associated with both outcome variables. We further find that individual beliefs that the wealthy are using government for their own purposes and that this influence needs to be curbed are positively related with preferences for redistribution. Moreover, beliefs that the working poor are deserving of government assistance are found to be strongly associated with support for income reduction in the country and willingness to pay more to assist the needy. Together, these attitudes toward the rich and poor appear to explain a greater share of the variation in predicted levels of support for redistribution, even more so compared to the effects of individual attitudes toward government that we, or indeed many existing studies, report. However, before definitive conclusions can be drawn from our cross-sectional analysis, researchers should make use of alternative analytical approaches to firmly establish causality. For instance, to better understand the mechanisms that translate individual attitudes and beliefs into support for redistributive policies, large sample surveys should be complemented by qualitative or behavioral research using interviews with people living in both Western and non-Western countries.

At the same time, researchers, whether quantitative and qualitative, should examine further where the individual attitudes toward government, as well as the rich and poor, come from. There is robust research about why individuals trust their government or why some governments are perceived to be corrupt, and we are beginning to understand better why people view the rich and poor as sympathetic or unsympathetic (van Oorschot et al., Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Laenen and Bart, Reference Laenen and Bart2017). Research on this latter stream of research remains critical not only in developing or transitional countries, but also in Western democracies. For example, research on the mechanisms for tackling income inequalities will remain critical in many countries. A potentially important lever to garner support for redistributive policies may not only be about nurturing positive attitudes toward government, but also about understanding individual orientations toward the rich and poor.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279423000120

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.