Introduction

Supervisor organizational embodiment (SOE) refers to the degree to which employees identify their supervisor with the organization (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010). Since Eisenberger et al.'s (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010) seminal conceptualization of SOE, researchers have demonstrated its contributions to multiple management areas, such as hospitality management (Dai, Hou, Chen, & Zhuang, Reference Dai, Hou, Chen and Zhuang2018) and perceived organizational support (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010; Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog, & Zagenczyk, Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013). Beyond its contributions to the broader discipline of management, leadership scholars have specifically integrated the role of SOE into abusive supervision (Mackey, McAllister, Brees, Huang, & Carson, Reference Mackey, McAllister, Brees, Huang and Carson2018; Shoss et al., Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013), transformational leadership (Stinglhamber, Marique, Caesens, Hanin, & De Zanet, Reference Stinglhamber, Marique, Caesens, Hanin and De Zanet2015), and leader–member exchange research (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010; Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham, & Buffardi, Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014; Hussain & Shahzad, Reference Hussain and Shahzad2018). Collectively, this body of literature has extended our understanding of when SOE strengthens leader attributes' impact on organizational outcomes.

More specifically, SOE has been associated with increasing our understanding of when employees blame their organizations for being victimized by abusive supervisors (Shoss et al., Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013). SOE has also been associated with enhancing our knowledge when ethical leaders cultivate organizational identification within their employees. Recent research has also revealed that upper-level managerial leadership styles impact SOE via supervisor psychological contract fulfillment (Rice, Massey, Roberts, & Sterzenbach, Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a). Although a growing number of scholars have featured SOE in management research, our understanding of SOE remains limited. This is because there are two significant limitations regarding SOE research. First, SOE has been primarily positioned as a novel moderator in management research (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Hou, Chen and Zhuang2018; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010, Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014; Hussain & Shahzad, Reference Hussain and Shahzad2018; Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, McAllister, Brees, Huang and Carson2018; Shoss et al., Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013; Stinglhamber et al., Reference Stinglhamber, Marique, Caesens, Hanin and De Zanet2015). Subsequently, the SOE literature has been constrained by the lack of examining its potential antecedents and outcomes (for an exception see Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a). Second, SOE is generally viewed as a social exchange concept (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010, Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a). As a result, this has hindered the field's ability to (1) extend the understanding of SOE, and its nomological network and (2) develop diverse theoretical insights regarding SOE. These limitations are significant because management research has long held that organizations are morally and legally responsible for the actions of supervisors (Levinson, Reference Levinson1965). Nonetheless, there is a scarce amount of research focused on the factors that can influence the development of SOE and the outcomes associated with SOE. We seek to address these limitations with our study.

One particular way the field can address the current limitations of SOE research is if SOE researchers were to follow the path of other supervisor-referent leadership concepts (e.g., supervisor inclusiveness, abusive supervision, supervisory ethical leadership). Notably, to (1) enhance our understanding and broaden the nomological networks of these particular concepts and (2) to examine both antecedents and outcomes of these concepts, management and leadership scholars have commonly relied on various trickle-down models. For example, scholars have proposed that abusive supervision (Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne, & Marinova, Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012), ethical leadership (Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009), organizational inclusiveness (Rice, Young, & Sheridan, Reference Rice, Young and Sheridan2021b), social undermining (Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020), and perceived integrity (Peng & Wei, Reference Peng and Wei2018) can trickle down from upper-level managers to lower-level employees via middle-level supervisors. Subsequently, if we are to accept (1) Eisenberger et al.'s (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010) conceptualization of SOE and (2) this conceptualization (i.e., based on employees' evaluations of those in supervisory positions) is similar to the conceptualizations of supervisory ethical leadership (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009), abusive supervision (Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012), supervisory inclusiveness (Rice, Young, & Sheridan, Reference Rice, Young and Sheridan2021b), supervisory undermining (Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020), and perceived supervisory support (Shanock & Eisenberger, Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006), then it is likely that organizational embodiment can also traverse multiple organizational levels. Subsequently, we leverage Bandura's (Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1986) social cognitive theory and argue organizational embodiment is transmitted from upper-level managers to middle-level supervisors to lower-level employees via a role-modeling effect. Thus, manager organizational embodiment (MOE) should trickle down to impact employee organizational embodiment (EOE) via SOE.

Given our theoretical framework, it is vital to note that ‘a common theme among these previous studies is each focuses on individual characteristics that moderate trickle-down effects’ (Ambrose, Schminke, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Schminke and Mayer2013: 680). Given its social cognitive properties, management researchers have commonly targeted neuroticism in studies rooted in social cognitive theory (e.g., Duffy, Shaw, Scott, & Tepper, Reference Duffy, Shaw, Scott and Tepper2006; Kiewitz, Restubog, Zagenczyk, Scott, Garcia, & Tang, Reference Kiewitz, Restubog, Zagenczyk, Scott, Garcia and Tang2012; Pavani, Fort, Moncel, Ritz, & Dauvier, Reference Pavani, Fort, Moncel, Ritz and Dauvier2021). Specific to our interest in the trickle-down effect of organizational embodiment, we acknowledge that some supervisors may seek to identify with the organizations more intentionally than others. This is because some supervisors may have a higher desire to fit in as part of the leadership team. To this end, research suggests that individuals high in neuroticism are more likely to feel unsure of themselves (Johnson, Morgeson, & Hekman, Reference Johnson, Morgeson and Hekman2012) and view themselves based on the social group with which they identify (Johnson & Morgeson, Reference Johnson and Morgeson2005). Subsequently, they seek the approval of those with whom they identify. Given that supervisors generally see themselves as extensions of their managers (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009), this suggests that highly neurotic supervisors should be more inclined to follow the lead of their managers concerning organizational embodiment and to reduce uncertainty and gain approval. Consequently, we believe that neuroticism was appropriate to include as a boundary condition in this study. We argue that MOE's influence on SOE should be stronger when the supervisor's neuroticism is high compared to low.

This study aims to answer two research questions: how organizational embodiment trickles down across multiple hierarchal levels, and when is this trickle-down effect strengthened? By addressing these two research questions, this study enhances our understanding of SOE in several ways. First, we integrate social cognitive theory into SOE research and explain organizational embodiment's role modeling influence. Social cognitive theory is commonly positioned as a complementary framework to social exchange concepts (e.g., Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009). Thus, we harmonize extant social exchange research of SOE with a social cognitive perspective of SOE. Second, by understanding how MOE impacts EOE via SOE, we extend the nomological network of SOE by identifying a likely antecedent and outcome of SOE. Thus, we attempt to expand the literature beyond viewing SOE as a moderator (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a). Third, we clarify this trickle-down effect of organizational embodiment by identifying when this effect is strengthened. Subsequently, we also examine a boundary condition of this particular trickle-down model and contribute to the amassed literature on how individual characteristics could impact various trickle-down effects (e.g., Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007; Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020; Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012; Mawritz, Dust, & Resick, Reference Mawritz, Dust and Resick2014a, Mawritz, Folger, & Latham, Reference Mawritz, Folger and Latham2014b; Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton, & Stacy, Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020). Our conceptual model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Theory and hypotheses development

Manager organizational embodiment and supervisor organizational embodiment

Recent SOE research provides the rationale for examining organizational embodiment as a trickle-down effect. Specifically, Rice et al. (Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a) proposed that ‘embodying one's employing organization is likely a learned behavior’ (p. 14). To this end, Bussey and Bandura (Reference Bussey and Bandura1999) proposed that ‘social cognitive theory characterizes learning from exemplars as modeling’ (p. 686) and ‘modeling is one of the most pervasive and powerful means of transmitting values, attitudes, and patterns of thought and behavior’ (p. 686). In management research, upper-level managers are commonly positioned as modeling exemplars for middle-level supervisors (Bormann & Diebig, Reference Bormann and Diebig2021; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Peng & Wei, Reference Peng and Wei2018). Subsequently, we rely on Bandura's (Reference Bandura1986) social cognitive theory to explain the relationship between MOE and SOE. Accordingly, we elevate Eisenberger et al.'s (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010) definition of SOE to the managerial level, we propose MOE refers to the degree to which supervisors identify their managers with the organization. This conceptualization is consistent with prior trickle-down studies that have elevated supervisory-level concepts to upper-level managers (e.g., Bormann & Diebig, Reference Bormann and Diebig2021; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Peng & Wei, Reference Peng and Wei2018).

As noted by social cognitive theorists (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009), ‘supervisors look to higher levels in the organization for the appropriate way to behave’ (p. 3). Mayer et al. (Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009) also proposed that supervisors likely view themselves as extensions of their managers and are prone to emulate their attitudes and conduct. This argument has been echoed by several other management scholars (e.g., Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020; Lord, Gatti, & Chui, Reference Lord, Gatti and Chui2016; Rice, Young, & Sheridan, Reference Rice, Young and Sheridan2021b; Yang, Reference Yang2020; Zhao & Guo, Reference Zhao and Guo2019). To this end, management and leader scholars have concluded that ‘trickle-down models suggest that if leaders at a higher level behave in a specific way, then leaders at lower levels will behave in a similar manner’ (Bormann & Diebig, Reference Bormann and Diebig2021: 2106). Based on this rationale, Mayer et al. (Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009) argued and demonstrated a positive relationship between top management ethical leadership and supervisory ethical leadership. While also adopting a social cognitive perspective, Mawritz et al. (Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012) argued and demonstrated that abusive manager behavior trickled down and positively impacted abusive supervisor behavior. They reasoned that ‘if supervisors see their higher-level managers engaging in abusive supervision, they may employ similar behavior’ (p. 330–331). Indeed, this trickle-down effect has been widely corroborated in management research (e.g., Li and Sun, Reference Li and Sun2015).

On the basis that embodying one's organization is regarded as a learned behavior (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a), we specifically argue that organizational embodiment is transmitted from upper-level managers to middle-level supervisors via a role-modeling effect. We propose that if middle-level supervisors generally perceive their upper-level managers as embodying the organization, then they are likely to emulate embodying the organization as well. Subsequently, employees will generally perceive these middle-level supervisors as embodying the organization. Thus, MOE should trickle down and positively impact SOE.

Hypothesis 1: MOE is positively related to SOE.

Supervisor organizational embodiment and employee organizational embodiment

Leveraging Eisenberger et al.'s (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010) definition of SOE, we propose that EOE refers to the degree to which supervisors identify their employees as embodying the organization. Our rationale is rooted in the work of Shanock and Eisenberger (Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006). They argued that ‘perceptions of organizational support have been found to develop among managerial level employees as well as among lower-level workers’ (p. 689). Similarly, we argue that organizational embodiment can be developed among upper-level managers, middle-level supervisors, and lower-level employees. Remaining consistent with our trickle-down model, we argue that SOE positively impacts EOE. Our rationale is that employees generally see their supervisors as credible role models and are likely to emulate embodying the organization.

Establishing the link between SOE and EOE is essential to our model. This is because management scholars have expressed the need to establish a conceptual and empirical link to parallel or similar constructs at the subordinate level (Ambrose, Rice, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021; Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020; Hirst, Walumbwa, Aryee, Butarbutar, & Chen, Reference Hirst, Walumbwa, Aryee, Butarbutar and Chen2016; Masterson, Reference Masterson2001; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Tepper & Taylor, Reference Tepper and Taylor2003; Ullah, Hameed, Kayani, & Fazal, Reference Ullah, Hameed, Kayani and Fazal2019; Zhang, Zhang, Xiu, & Zheng, Reference Zhang, Zhang, Xiu and Zheng2020). For example, in their study of the trickle-down effects of organizational justice, Wo, Ambrose, and Schminke (Reference Wo, Ambrose and Schminke2015) found a positive relationship existed between (1) supervisors' perceptions of interpersonal justice and subordinates' perceptions of interpersonal justice and (2) supervisors' perceptions of informational justice and subordinates' perceptions of informational justice. Similarly, Ambrose, Schminke, and Mayer (Reference Ambrose, Schminke and Mayer2013) demonstrated that supervisors' perceptions of interactional justice positively influenced subordinates' shared perceptions of interaction justice. Consistent with this stream of research, we argue that SOE should trickle down and positively influence EOE.

Hypothesis 2: SOE is positively related to EOE.

The mediating role of SOE

Comprehensively, a trickle-down model explains how perceptions at higher hierarchal levels influence perceptions and subsequent reactions, as well as the effect of these reactions on perceptions and subsequent responses, at lower hierarchal levels (Aryee et al., Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020; Tepper, Duffy, Henle, & Lambert, Reference Tepper, Duffy, Henle and Lambert2006). Typically, to illustrate this trickle-down conceptualization, social cognitive theorists have commonly positioned a supervisory-level concept as the theoretical link between the upper manager-level concept and the subordinate-level concept. For example, in their trickle-down model of ethical leadership, Mayer et al. (Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009) argued and demonstrated that supervisory ethical leadership was a critical link between top management ethical leadership and employee citizenship behavior. Similarly, in their trickle-down model of abusive supervision, Mawritz et al. (Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012) empirically showed that the relationship between abusive manager behavior and employee deviance was mediated by abusive supervisor behavior. Shanock and Eisenberger (Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006) also distinctly positioned subordinates' perceptions of supervisor support as the link between supervisors' perceptions of organizational support and subordinates' perceptions of organizational support.

Similarly, we position SOE as a conceptual linkage between MOE and EOE. Specifically, we argue that managers' organizational embodiment positively impacts supervisors' embodiment, which in turn positively influences that of their subordinates. This rationale helps explain how MOE affects EOE (i.e., from managers to supervisors to employees). Moreover, our rationale is guided by extant literature suggesting that employees form certain perceptions and beliefs about their immediate supervisors and view them as a representation and a reflection of their organization's values and culture (Liden, Bauer, & Erdogan, Reference Liden, Bauer and Erdogan2004; Tekleab & Taylor, Reference Tekleab and Taylor2003). Taken together, this suggests that MOE impacts EOE via SOE.

Hypothesis 3: SOE mediates the relationship between MOE and EOE.

The moderating role of supervisor neuroticism

As mentioned earlier, we focus on supervisor neuroticism's moderating influence. Neuroticism represents individual differences in the tendency to experience distress (McCrae & John, Reference McCrae and John1992), and typical behaviors associated with this factor include being anxious, depressed, embarrassed, emotional, worried, and insecure (Barrick & Mount, Reference Barrick and Mount1991; Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1983). Specifically, we targeted neuroticism because research suggests that it can influence individual reactions to concepts similar to the organizational embodiment, such as organizational identification (Johnson, Morgeson, & Hekman, Reference Johnson, Morgeson and Hekman2012) and continuance commitment (Erdheim, Wang, & Zickar, Reference Erdheim, Wang and Zickar2006).

Notably, highly neurotic individuals feel more apprehensive about facing a new work environment (Erdheim, Wang, & Zickar, Reference Erdheim, Wang and Zickar2006). Highly neurotic individuals are also more likely to worry that they are not accepted by other group members or fit in (Johnson & Morgeson, Reference Johnson and Morgeson2005). As noted by Johnson, Morgeson, and Hekman (Reference Johnson, Morgeson and Hekman2012), highly neurotic individuals are ‘motivated to reduce this uncertainty with clearer social self-definitions. As a result, neurotic individuals will tend to take the uncertainty-reducing path to identification and have higher levels of cognitive identification with groups’ (p. 1145). In the context of our trickle-down model, highly neurotic supervisors should have a greater tendency to want to be accepted by their managers, as this is the social group that they would identify with, being part of the management team (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009). Subsequently, highly neurotic supervisors should be more likely to follow the lead of their managers. Thus, if they perceive that their managers do not embody the organization, then they are likely to reduce their organizational embodiment. Conversely, if they perceive that their managers embody the organization, they are also expected to represent it.

On the other hand, supervisors with lower levels of neuroticism are generally less concerned with being accepted by others and are more likely to exhibit consistent attitudes and behavior. As such, the trickle-down effect should be weaker as they are less likely to follow the lead of managers than their counterparts. Taken together, this suggests the positive relationship between MOE and SOE is stronger when supervisor neuroticism is high compared to low. Extending this moderating influence of supervisor neuroticism to our full trickle-down model, we also argue for a first-stage moderated mediation model. Thus, the indirect effect of MOE on EOE through SOE is stronger when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high compared to relatively low.

Hypothesis 4: The positive relationship between MOE and SOE is stronger when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high compared to relatively low.

Hypothesis 5: The indirect effect of MOE on EOE through SOE is stronger when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high compared to relatively low.

Research methodology

Transparency and openness

With respect to our study, we describe our sampling/recruitment approach, the removal of missing data, and survey measures. The data set and analyses outputs are available at https://osf.io/3hb5a/?view_only=157a30c8e4b74118ab297cb1e5a398cd. G*power (version 3.1; Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) was used to conduct power analyses. LISREL (version 9.30; Jöreskog & Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom2006) was used to conduct confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). Linear regression (SPSS version 28.0) and PROCESS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013) were used for hypotheses testing. The study's design and analyses were not preregistered.

Sample and procedure

Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Bonner, Greenbaum, & Mayer, Reference Bonner, Greenbaum and Mayer2016; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020), the data were collected from supervisor–employee pairings from a variety of organizations in different industries located in southeastern United States. Qualtrics was used to administer the online surveys to working adults (i.e., at least 20 work hours per week; Probst, Lee, & Bazzoli, Reference Probst, Lee and Bazzoli2020; Quade, Greenbaum, & Petrenko, Reference Quade, Greenbaum and Petrenko2017). To access supervisor–employee dyads, a total of 316 undergraduate students were invited to participate. They served as organizational recruits in exchange for extra credit to recruit a lower-level employee. The lower-level employee was accountable for completing their survey and forwarding their direct supervisor the ‘supervisor’ survey. This dyadic data collection methodology is consistent with prior SOE studies (i.e., Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010; Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014; Hussain & Shahzad, Reference Hussain and Shahzad2018; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a). Consistent with prior research (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014; Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum, & Kuenzi, Reference Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum and Kuenzi2012), we took several precautions to verify that the questionnaires were submitted by the appropriate individuals. We emphasized the importance of truthfulness in the data collection process. To increase the validity of the data, we documented and examined IP addresses and timestamps to verify if the completed surveys were submitted from different computers at different times. We collected surveys from 188 direct supervisors and 206 lower-level employees. Some respondents ended their participation before completing their respective surveys. These types of partial or missing responses were regarded as drop-out responses (Wouters, Maesschalck, Peeters, & Roosen, Reference Wouters, Maesschalck, Peeters and Roosen2014). Subsequently, the drop-out rate for employee responses was 37.86% and the drop-out rate for supervisor responses was 31.91%. The drop-out analysis did not reveal any patterns and suggested that the data were missing completely at random. After removing missing data, our final sample size consisted of usable 128 supervisor–employee dyads.

Lower-level employees were 44% male. The majority were Caucasian (68%). Other ethnicities represented in the sample were Hispanic American (16%), African American (8%), Asian American (4%), and other (4%). Lower-level participants were approximately 25 years old (SD = 7.23), on average. Immediate supervisors were 43% female. The majority of these supervisors were Caucasian (65%), followed by Hispanic American (16%), African American (10%), Asian American (2%), other (4%), and Native American (1%). On average, immediate supervisors were approximately 38 years old (SD = 11.79).

Whereas the lower-level employee survey contains measures of SOE, trait cynicism, current tenure with supervisor, demographics, and industry, the direct supervisor survey contained measures of MOE, EOE, neuroticism, demographics, and organizational tenure. Following Becker's (Reference Becker2005) recommendations, we accounted for industry impact (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a), employee current tenure with supervisor (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010, Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014), supervisor organizational tenure (Shoss et al., Reference Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013), and employee cynicism (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a) as prior research suggests these variables can impact our model.

Measures

Unless otherwise noted, the ratings were based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘strongly agree’).

Manager organizational embodiment (MOE)

Supervisors responded to the nine-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010), with a referent shift to their managers. Sample statements included ‘My manager is a characteristic of my organization’ and ‘My manager is a representative of my organization.’

Supervisor organizational embodiment (SOE)

Employees responded to the nine-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010). Sample statements included ‘My supervisor is a characteristic of my organization’ and ‘My supervisor is a representative of my organization.’

Employee organizational embodiment (EOE)

Supervisors responded to the nine-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010), with a referent shift to their employees. Sample statements included ‘This employee is a characteristic of my organization’ and ‘This employee is a representative of my organization.’

Neuroticism

Supervisor’ neuroticism was assessed using the 10-item neuroticism scale from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) established by Goldberg (Reference Goldberg, Mervielde, Deary, De Fruyt and Ostendorf1999). Supervisors responded to statements such as ‘I dislike myself’ and ‘I panic easily.’ Dyadic studies (e.g., Wilson, DeRue, Matta, Howe, & Conlon, Reference Wilson, DeRue, Matta, Howe and Conlon2016), particularly ones that test trickle-down effects (e.g., Rice et al., Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020) commonly use the IPIP scale (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg, Mervielde, Deary, De Fruyt and Ostendorf1999) to measure personality traits. Thus, we thought this measure was an appropriate choice.

Employee cynicism

Employees responded to the five-item scale developed by Wrightman (Reference Wrightman1974). Sample statements included ‘Most people would tell a lie if they could gain by it’ and ‘People pretend to care about one another more than they really do.’

Data analysis and results

Table 1 contains bivariate correlations, scale reliabilities, means, and standard deviations. We conducted CFA via LISREL (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom2006) to demonstrate variable distinctiveness and to assess model fit. Regarding our hypothesized model, the CFA results suggested that our four-factor model had an acceptable fit (χ2 = 875.47, df = 458, p < .01; CFI = .90; IFI = .90; SRMR = .06; RMSEA = .08). Our model's χ2/degrees of freedom ratio was 1.91, below the threshold of 3 that suggests a satisfactorily fit (Kline, Reference Kline2005). Our model had a superior fit compared to a three-factor model (combined MOE and SOE) (χ2 = 1906.52, df = 461, p < .01; CFI = .65; IFI = .65; SRMR = .16; RMSEA = .23) and a two-factor model (combined MOE, SOE, and EOE into organizational embodiment and supervisor neuroticism) (χ2 = 2045.15, df = 463, p < .01; CFI = .62; IFI = .62; SRMR = .17; RMSEA = .16).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, bivariate correlations, and scale reliabilities

Note. **p < .01; *p < .05; N = 128; reliabilities are along the diagonals. Industry: 1 = Finance/Insurance/Real Estate, 2 = Science/Engineering/Architecture, 3 = Computer/Information Systems, 4 = Education/Training/Library, 5 = Healthcare, 6 = Community/Social Services, 7 = Art/Design/Entertainment/Sports, 8 = Transportation/Logistics, 9 = Retail, 10 = Manufacturing/Construction, 11 = Restaurants/Food Services/Grocery, 12 = Other.

Scale reliabilities are bolded and italicized along the diagonals

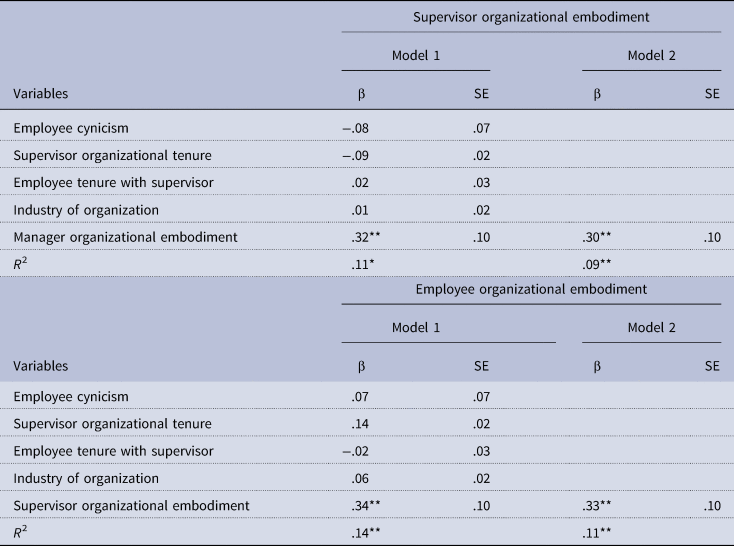

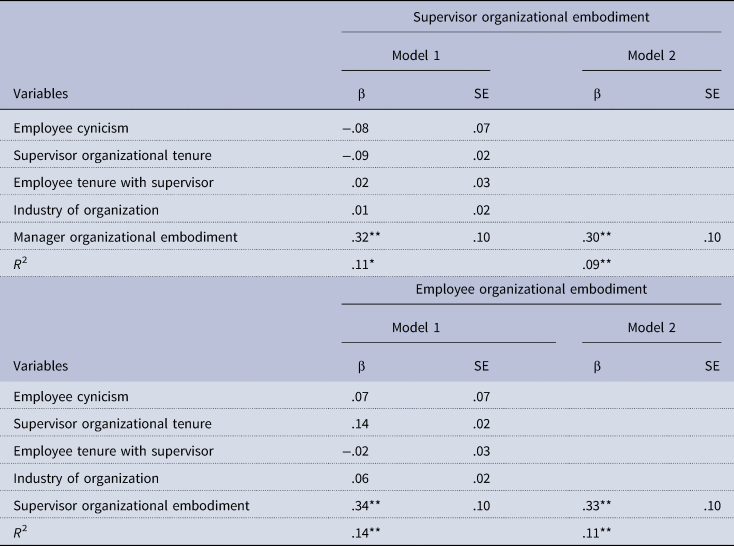

We conducted our analyses with and without control variables. The findings were largely similar. Subsequently, we report the results without control variables (Becker, Reference Becker2005). Linear regression was used to test Hypotheses 1 and 2. Hypothesis 1 stated that MOE is positively related to SOE. The results revealed a positive and significant relationship between MOE and SOE (β = .30, p < .01). Thus, Hypothesis 1 received support. Hypothesis 2 stated that SOE is positively related to EOE. The results revealed a positive and significant relationship between SOE and EOE (β = .33, p < .01). The results for Hypotheses 1 and 2 with and without control variables can be located in Table 2.

Table 2. Regression results with and without control variables for Hypotheses 1 and 2

Note. **p < .01; *p < .05; N = 128; SE = standard error.

The remaining hypotheses were tested using Hayes (Reference Hayes2013) PROCESS macro. Hypothesis 3 stated that SOE mediates the relationship between MOE and EOE. PROCESS results revealed a significant indirect effect of MOE on EOE through SOE (indirect effect = .05; LCI = .004; UCI = .119). Thus, Hypothesis 3 received support. Additionally, MOE exhibited a direct effect on EOE (B = .81; p < .01; LCI = .648; UCI = .981). This suggests partial mediation. Table 3 contains the mediation results for Hypothesis 3 with and without control variables.

Table 3. PROCESS macro (Model 4 and Model 7) results with and without control variables for Hypotheses 3 and 5

Note. Model 1 conducted with control variables; Model 2 conducted without control variables; **p < .01; *p < .05; SOE, supervisor organizational embodiment; EOE, employee organizational embodiment; SE, standard error; LCI, lower confidence interval; UCI, upper confidence interval; 5,000 bootstraps; 95% bias corrected.

Notably, a high bivariate correlation exists between MOE and EOE (r = .69; p < .01). High bivariate correlations are common among trickle-down studies (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Shanock & Eisenberger, Reference Shanock and Eisenberger2006; Wo, Ambrose, & Schminke, Reference Wo, Ambrose and Schminke2015). For example, Mayer et al. (Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009) found a high bivariate correlation between top management ethical leadership and supervisory (r = .72; p < .01). Wo, Ambrose, and Schminke (Reference Wo, Ambrose and Schminke2015) found a high bivariate correlation between supervisors' perceptions of interpersonal justice and role modeling influence (r = .63; p < .01) and supervisors' perceptions of informational justice and role modeling influence (r = .65; p < .01). Nonetheless, our high bivariate correlation may be attributed to common method variance, endogeneity, and/or simultaneity.

Due to these potential concerns, we conducted a supplemental mediation analysis using LISREL. Scholars have proposed and demonstrated that the maximum likelihood technique implemented by structural equation modeling could be used to reduce these concerns (Ambrose, Rice, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021; Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, & Lalive, Reference Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart and Lalive2010; Cameron & Trivedi, Reference Cameron and Trivedi2005; Greene, Reference Greene2008; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2003; Shaver, Reference Shaver2005). As noted by Ambrose, Rice, and Mayer (Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021), ‘this particular procedure allows the off-diagonal elements of the Ψ matrix to be estimated, which entails the common practice ‘fixing’ (i.e., setting to zero) the off-diagonal elements in order to properly identify the model, and when researchers fix the off-diagonal elements of the Ψ matrix’ (p. 88). This imposes the assumption that the error terms across equations are not correlated (Shaver, Reference Shaver2005). Subsequently, researchers have used this procedure when these issues (e.g., common method variance, simultaneity, endogeneity, measurement error, omitted variables) have potentially existed in cross-sectional studies (Ambrose, Rice, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021; Hinkin & Schriesheim, Reference Hinkin and Schriesheim2015; Lu, Chang, & Chang, Reference Lu, Chang and Chang2015; Mawritz, Dust, & Resick, Reference Mawritz, Dust and Resick2014a, Reference Mawritz, Folger and Latham2014b; Rice & Reed, Reference Rice and Reed2021). Using this particular methodology, the results revealed a significant indirect effect (standardized estimate = .06, t-value = 2.06, p < .05), providing additional support for Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 stated that the positive relationship between MOE and SOE is stronger when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high compared to relatively low. PROCESS results revealed a positive and significant interaction effect between MOE and supervisor neuroticism on SOE (B = .38; p < .01) and explained an additional 9% variance. Specifically, the slope was significant at relatively high levels of supervisor neuroticism (t-value = 4.73; LCI = .306; UCI = .746), but not significant at relatively low levels of supervisor neuroticism (t-value = −.34; LCI = −.288; UCI = .204). Thus, Hypothesis 4 received support. The results with and without control variables for Hypothesis 4 are located in Table 4. As depicted in Figure 2, the positive slope is more pronounced when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high compared to relatively low.

Figure 2. Simple slopes graph for Hypothesis 4.

Table 4. PROCESS macro (Model 1) results with and without control variables for Hypothesis 4

Note. **p < .01; *p < .05; B, unstandardized coefficients; SE, standard error; MOE, manager organizational embodiment; supv, supervisor; 5,000 bootstraps; 95% bias corrected.

Hypothesis 5 stated the indirect effect of MOE on EOE through SOE is stronger when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high compared to relatively low. PROCESS results revealed a significant conditional indirect effect when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high (boot effect = .08; LCI = .008; UCI = .178), but not when supervisor neuroticism is relatively low (boot effect = −.01; LCI = −.048; UCI = .034). As such, Hypothesis 5 received support. The conditional indirect results with and without control variables are located in Table 3. Notably, Hayes (Reference Hayes2015) also argued that ‘A bootstrap confidence interval for the index of moderated mediation that does not include zero provides more direct and definitive evidence of moderation of the indirect effect’ (p. 11). With the respect to our results, the index of moderated mediation was also significant (index = .06; boot LCI = .005; boot UCI = .128), providing additional support for Hypothesis 5. The results with and without control variables for Hypothesis 5 can be located in Table 3.

Discussion

In our multi-source field study, we proposed and tested a trickle-down model of organizational embodiment. We hypothesized that EOE is positively influenced by MOE via SOE. Additionally, we investigated the moderating influence of supervisor neuroticism. We found support that MOE was positively related to SOE, and SOE was positively related to EOE. Furthermore, supervisor neuroticism strengthened the positive relationship between MOE and SOE when relatively high compared to relatively low. Subsequently, our trickle-down model of organizational embodiment was supported.

Theoretical implications

Our research contributes to SOE research. This is because SOE has been regarded as a moderator in most management studies. Therefore, our study extends the SOE research that seeks to identify its antecedents. For example, Rice et al. (Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a) used social exchange theory to argue and demonstrate that upper-level managerial ethical leadership (i.e., positively) and upper-level managerial abusive leadership (i.e., negatively) impact SOE via supervisor psychological contract fulfillment. Our study joins this section of SOE research as we relied on social cognitive theory to argue and demonstrate that MOE positively impacts SOE. To this end, our study provided insights regarding another likely antecedent of SOE. We extend social cognitive theory to explain why SOE impacts EOE as well. Subsequently, our study is one of a few studies that identify an outcome associated with SOE.

Given our theoretical framework, our study contributes to social-cognitive research in two ways. First, social cognitive theory provided the conceptual basis for the trickle-down predictions. Although the social cognitive theory has often been used in prior leadership studies (Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Ullah et al., Reference Ullah, Hameed, Kayani and Fazal2019; Wo, Ambrose, & Schminke, Reference Wo, Ambrose and Schminke2015; Yang, Reference Yang2020), we contribute to this literature by integrating social cognitive theory into SOE research. Consistent with social cognitive research, supervisors emulate the embodying the organization due to their managers such that organizational embodiment trickles down, positively influencing employees' willingness to embody the organization as well. To this end, we were able to extend the nomological network of trickle-down studies. Second, our study contributes to the growing body of trickle-down models that focuses on boundary conditions. Whereas scholars have sought to explain when workplace structure (Ambrose, Rice, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021), workplace hostility (Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012), core self-evaluations (Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012), moral identity (Rice, Young, & Sheridan, Reference Rice, Young and Sheridan2021b), and conscientiousness (Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Eissa, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Eissa2012; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020) impact various trickle-down models, we add to this compilation of boundary conditions by explaining the impact of supervisor neuroticism. We find that supervisor neuroticism accentuates the trickle-down effect of organizational embodiment.

Our study also contributes to neuroticism research. Whereas most prior research examined the negative effect of neuroticism in the workplace (Eissa & Lester, Reference Eissa and Lester2017; Garcia, Wang, Lu, Kiazad, & Restubog, Reference Garcia, Wang, Lu, Kiazad and Restubog2015; Taylor & Kluemper, Reference Taylor and Kluemper2012; Wang, Repetti, & Campos, Reference Wang, Repetti and Campos2011), a smaller number of scholarly work on neuroticism has focused on acknowledging and embracing its amplification effect on organizations (Johnson & Morgeson, Reference Johnson and Morgeson2005; Johnson, Morgeson, & Hekman, Reference Johnson, Morgeson and Hekman2012). Our study extends the latter. Specifically, our findings suggest that highly neurotic supervisors are very reactive to role-modeling. Consistent with this research, our findings propose that employees observe others in their workplace for guidance in assessing what conduct is appropriate. Subsequently, supervisors with a high level of neuroticism particularly pay attention to their upper managers' leadership attitudes and behaviors in determining the extent to which they should embody the organization.

Practical implications

One practical implication is that supervisors can either be perceived as embodying the organization and acting as model organizational members or as separate from the organization and acting as independent agents. Nonetheless, in order to push supervisors toward embodying the organization, organizations and organizational leaders should be aware that embodying the organization can be understood as a learned behavior. As such, if organizations and managers desire for supervisors to embody their organizations, it is important that managers model this embodiment. This is also important because employees perceive their supervisors as an extension of their organization and represent to a high degree the values and culture of their institution (Liden, Bauer, & Erdogan, Reference Liden, Bauer and Erdogan2004; Tekleab & Taylor, Reference Tekleab and Taylor2003). It is also important to note that organizational embodiment is not limited to those in managerial and supervisory positions. To this end, all organizational members of the organization's management team (i.e., managers and supervisors) should be encouraged to represent the organization well, such as lower-level employees, new hires, and interns. Indeed, organizations are morally responsible for organizational agents who represent them (Levinson, Reference Levinson1965). Subsequently, it is vital for all employees, particularly those in leadership positions, to understand this moral responsibility.

Another practical implication is that many supervisors, despite their high ranking within their organization, still exhibit a dependency on their managers for guidance. Additionally, having an elevated position in the organization does not necessarily reduce the individual's need for approval. Particularly, highly neurotic supervisors are even more so concerned about their managers' approval. This can be both to their detriment and benefit. Supervisors with relatively high levels of neuroticism willingness to embody the organization are dependent on their managers' embodying the organization. When MOE was relatively low, SOE was hindered. When MOE was relatively high, SOE was enhanced. On the other hand, their counterparts with relatively low levels of neuroticism were more consistent regarding embodying the organization.

Limitations and future research

As with any study, our study has limitations that must be noted. First, the data are cross-sectional. Subsequently, our ability to make causal inferences is limited. However, research methodologists have suggested that directional hypotheses can be proposed when prior longitudinal or experimental studies have established causality, and a substantial amount of theory-based research exists (MacKinnon, Coxe, & Baraldi, Reference MacKinnon, Coxe and Baraldi2012). we believe this is the case as extant research supports the trickle-down model (Ambrose, Rice, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021; Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Ullah et al., Reference Ullah, Hameed, Kayani and Fazal2019; Wo, Ambrose, & Schminke, Reference Wo, Ambrose and Schminke2015; Yang, Reference Yang2020). Additionally, as noted by Ambrose, Schminke, and Mayer (Reference Ambrose, Schminke and Mayer2013), ‘This limitation is especially germane in examining trickle-down effects, which by their very nature unfold over time and across organizational levels’ (p. 686). Thus, multi-source, cross-sectional research designs are frequently used to test various trickle-down models (e.g., Ambrose, Schminke, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Schminke and Mayer2013; Bormann & Diebig, Reference Bormann and Diebig2021; Eissa, Wyland, & Gupta, Reference Eissa, Wyland and Gupta2020; Jordan, Brown, Treviño, & Finkelstein, Reference Jordan, Brown, Treviño and Finkelstein2013; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Mayer, Hoobler, Wayne and Marinova2012; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020). Nonetheless, our findings should be viewed in terms of correlation, not causality. Another limitation is that we used dyadic data. Thus, only one employee rated SOE. This prevented an aggregate score of SOE. However, we believe this limitation is minor because the majority of SOE research is based on dyadic studies (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010, Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Massey, Roberts and Sterzenbach2021a).

Common method variance may be a potential concern due to all the data being collected via surveys. To mitigate this concern, we took steps recommended by research methodologists (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). First, the data are multi-source. Second, we assured participants that all responses would be anonymous. Third and similar to other multi-level research (e.g., Letwin et al., Reference Letwin, Wo, Folger, Rice, Taylor, Richard and Taylor2016), we conducted a Harman single-factor test. Regarding the 37 items, seven factors emerged with an eigenvalue that was greater than one, and no factor explained a majority of the variance (Williams, Cote, & Buckley, Reference Williams, Cote and Buckley1989). Fourth, we conducted supplemental mediation analyses using the maximum likelihood procedure (Ambrose, Rice, & Mayer, Reference Ambrose, Rice and Mayer2021), which can account for common method variance (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart and Lalive2010; Shaver, Reference Shaver2005). Fifth, we were able to demonstrate a significant interaction effect between MOE and supervisor neuroticism on SOE. This reduces the possibility of the data being significantly impacted by common method variance. As argued and demonstrated by research methodologists (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010), ‘common method variance cannot create an artificial interaction’ (p. 469). Although we believe common method variance is not a major concern, we cannot completely rule it out.

One final limitation was our sample size. Although we had 128 supervisor–employee dyads, this can be considered somewhat small. Small sample sizes can lead to insufficient power to detect effect sizes. Specifically, our power analysis (G*Power, Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) revealed we had appropriate power to detect small, medium, and large effect sizes. Our sample size is also in line with other dyadic research (e.g., 116 in Byza, Schuh, Dörr, Spörrle, & Maier, Reference Byza, Schuh, Dörr, Spörrle and Maier2017; 135 dyads in Eisenbeiss & van Knippenberg, Reference Eisenbeiss and van Knippenberg2015; 123 dyads in Lussier, Hartmann, & Bolander, Reference Lussier, Hartmann and Bolander2021; 124 dyads in Rice et al., Reference Rice, Young, Johnson, Walton and Stacy2020; 114 dyads in Schuh, Zhang, & Tian, Reference Schuh, Zhang and Tian2013).

Despite our study's limitations, it can be foundational for future researchers. The avenue regarding the examination of antecedents of SOE is wide open. Given the social cognitive framework, we focused on the influence of MOE. However, future researchers can leverage different theoretical frameworks to uncover new antecedents. Future researchers may seek to extend the investigation of outcomes associated with SOE. Given its social exchange ties (Eisenberger et al., Reference Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales and Steiger-Mueller2010, Reference Eisenberger, Shoss, Karagonlar, Gonzalez-Morales, Wickham and Buffardi2014), it is likely that SOE can impact employee outcomes, such as in-role performance, citizenship behavior, affective commitment, and turnover intentions. This type of empirical examination regarding SOE and its outcomes and antecedents is needed to continue to move the SOE research beyond it being viewed primarily as a moderator. The relationship between MOE and SOE warrants further investigation as well. Whereas we focused on supervisor neuroticism, future researchers may examine other individual characteristics and situational factors. These research investigations should include both first-stage, second-stage, and dual-stage moderators. Additionally, future research may integrate potential mediators to enhance our understanding of how MOE impacts SOE or how SOE impacts EOE.

Conclusion

In summary, we believe that developing and demonstrating the trickle-down effect of organizational embodiment produced insightful and useful findings. Our study indicated that organizational embodiment extends beyond that supervisor level and has implications for upper-level managers and lower-level employees. Our study also demonstrated the significance of examining the joint impact of MOE and supervisor neuroticism on SOE and subsequently EOE. Our findings suggest when supervisor neuroticism is relatively high, the transmission of the organizational embodiment trickle-down effect is strengthened. It is evident that our understanding of SOE is enhanced by considering the organizational embodiment from a social cognitive framework. We hope that our study inspires future research to explore other antecedents and outcomes of SOE via diverse theoretical frameworks.