Introduction

In a volatile marketplace, it is important to retain talented employees for the achievement of organizational sustainability (Kravariti, Voutsina, Tasoulis, Dibia, & Johnston, Reference Kravariti, Voutsina, Tasoulis, Dibia and Johnston2021). However, supervisors' negative behaviors toward their followers in the form of intimidation, rudeness, and hostile behaviors erode employee morale, impede effective service delivery, and give rise to increased employee turnover (cf. Albashiti, Hamid, & Aboramadan, Reference Albashiti, Hamid and Aboramadan2021; Yu, Xu, Li, & Kong, Reference Yu, Xu, Li and Kong2020). Specifically, abusive supervision, which is a destructive supervisory practice in the workplace, is defined as ‘… the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact’ (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000: 178). Research has documented that it exerts a deleterious influence on employees' work-related outcomes such as helping behavior, service performance, quitting intentions, and work engagement (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Haar, De Fluiter, & Brougham, Reference Haar, De Fluiter and Brougham2016; Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021; Zhao & Guo, Reference Zhao and Guo2019). It is evident in the literature that employees who work under supervisors constantly displaying behaviors that are abusive experience adverse health-related problems such as emotional exhaustion and depression (Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, Reference Aryee, Chen, Sun and Debrah2007; Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter, & Kacmar, Reference Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter and Kacmar2007; Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). On the other hand, abusive supervisors experience guilt over their destructive practices when they find that their direct manager does not display abusive supervision (Shum, Ausar, & Tu, Reference Shum, Ausar and Tu2020).

In addition, Zhang and Liao's (Reference Zhang and Liao2015) and Mackey, Frieder, Brees, and Martinko's (Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017) past meta-analytic investigations present several studies that have examined affective organizational commitment (AOC), job satisfaction (JSAT), and turnover intentions as the consequences of abusive supervision. In Mackey et al.'s (Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017) inquiry, abusive supervision has been negatively associated with AOC and JSAT, while it has been positively linked to turnover intentions. The findings of Mackey, Ellen, McAllister, and Alexander's (Reference Mackey, Ellen, McAllister and Alexander2021) recent systematic review and meta-analytic study corroborates the findings of Zhang and Liao (Reference Zhang and Liao2015) and other relevant pieces (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone, & Duffy, Reference Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone and Duffy2008). These outcomes are also highlighted in Yu et al.'s (Reference Yu, Xu, Li and Kong2020) systematic review of abusive supervision in hospitality and tourism. Yet there is no evidence about the detrimental (direct) impact of abusive supervision on on-the-job embeddedness (JEM) in the pertinent literature. This is surprising because abusive supervisors exhibit hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors to their subordinates, erode subordinates' morale, and undermine subordinates' task and contextual performances (Shum, Reference Shum2021; Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021; Zhao & Guo, Reference Zhao and Guo2019).

As a retention strategy, JEM is one of the most important work outcomes that can be influenced by abusive supervision (Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021). JEM refers to the combined influences that keep employees in their jobs (Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). According to Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001), JEM can be on-the-JEM and/or off-the-JEM. On-the-JEM reflects influences in the company that inform employees' decision to remain in the job, while off-the-JEM denotes influences in the residential community that keep employees in the job (Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, & Holtom, Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004). JEM is composed of ‘links’, ‘fit’, and ‘sacrifice’ (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). Links highlight the ties workers have with other individuals and groups in and outside the company, while fit represents the extent to which employees' career goals and personal values are congruent with those of the company and the residential community (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004). Sacrifice denotes the perceived benefits that would be forfeited when employees voluntarily leave the company or their neighborhood (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004).

JEM has gained prominence in the service literature because of its ability to explain significant variance in both turnover and non-turnover variables like life satisfaction, AOC, and contextual and task performances (e.g., Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020; Zia, Naveed, Bashir, & Iqbal, Reference Zia, Naveed, Bashir and Iqbal2022). JEM has also been identified with various predictors such as servant leadership and high-performance work practices (Teng, Cheng, & Chen, Reference Teng, Cheng and Chen2021; Zia et al., Reference Zia, Naveed, Bashir and Iqbal2022). However, abusive supervision, which is a barrier against the development of quality relationship and mutual trust between employees and the supervisor, denotes the lack (or absence) of fit between the supervisor's values and that of employees and may make employees sacrifice a number of benefits in the organization. As claimed by Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001), individuals quit not only due to negative attitudes such as JSAT and AOC but also because of precipitating events or shocks. In light of this, we consider abusive supervision as one of the negative work-related shocks (Holtom, Burton, & Crossley, Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012). Under these circumstances, it would be very difficult to retain talented workers within an organization.

Surprisingly, there is only one empirical piece, which has reported the indirect effect of abusive supervision on JEM so far (Dirican & Erdil, Reference Dirican and Erdil2022). In addition, abusive supervision exacerbates burnout and has a detrimental impact on work-related consequences such as AOC, turnover intentions, and JSAT (e.g., Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Xu, Li and Kong2020; Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021). Nonetheless, no empirical piece has investigated whether abusive supervision has a more impact on on-the-JEM than on AOC, JSAT, and quitting intentions. More importantly, no empirical study has gauged the association of abusive supervision with withdrawal cognition by comparing on-the-JEM as a mediator to the abovementioned traditional attitudinal constructs as potential mediators so far.

In addition, the hospitality and tourism literature shows empirical pieces about the underlying mechanism (e.g., work engagement, psychological contract breach, perceived organizational support) through which abusive supervision is related to turnover intentions and other attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Park & Kim, Reference Park and Kim2019; Xu, Martinez, Van Hoof, Tews, Torres, & Farfan, Reference Xu, Martinez, Van Hoof, Tews, Torres and Farfan2018). An extensive search in the pertinent literature also demonstrates studies regarding the mechanism (e.g., JSAT, AOC, and employee silence) underlying the relationship between abusive supervision and affective and behavioral consequences (Guan & Hsu, Reference Guan and Hsu2020; Peltokorpi & Ramaswami, Reference Peltokorpi and Ramaswami2021; Wang, Hsieh, & Wang, Reference Wang, Hsieh and Wang2020). However, no empirical study has tested whether the mediation impact of on-the-JEM in the linkage between abusive supervision and proclivity to quit is stronger than the mediation effects of the abovementioned negative attitudes or traditional attitudinal constructs so far.

Purpose

In light of this, our paper examines the effect of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM and compares it to the effect of abusive supervision on AOC, JSAT, and turnover intentions. Our paper investigates whether the mediation impact of on-the-JEM in the association between abusive supervision and turnover intentions is stronger than the mediation effects of the aforesaid traditional attitudinal constructs.

Workers' turnover intentions denote their conscious thoughts about quitting (Jiang, Liu, McKay, Lee, & Mitchell, Reference Jiang, Liu, McKay, Lee and Mitchell2012). Employee turnover has been a prevailing issue in the hospitality and tourism industry, given the undesirable consequences it has on companies (e.g., Tan, Sim, Goh, Leong, & Ting, Reference Tan, Sim, Goh, Leong and Ting2020; Tews & Stafford, Reference Tews and Stafford2020). Employee voluntary turnover may leave hospitality companies with huge cost because employee replacement, training, and socialization might require investment of resources such as time and money (Guzeller & Celiker, Reference Guzeller and Celiker2019). Karatepe and Shahriari (Reference Karatepe and Shahriari2014) asserted that employees with higher proclivity to leave the company eroded their colleagues' morale and impede effective service delivery.

AOC and JSAT are among the traditional organizational outcomes that have been largely examined in the literature (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). AOC signifies workers' ‘…emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in, the organization’ (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990: 1), and JSAT refers to ‘the pleasurable emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job as achieving or facilitating the achievement of one's job values’ (Locke, Reference Locke1969: 316).

Contribution

Assessing the abovementioned relationships is relevant and significant. First, we do not know whether abusive supervision has a more negative impact on on-the-JEM than AOC and JSAT. We do not know whether abusive supervision exerts a more positive effect on on-the-JEM than turnover intentions. Our paper fills in this lacuna by gauging the above relationships. Testing these relationships is important because stress resulting from resources losses or threats may have a greater impact on employees' on-the-JEM than their AOC, JSAT, and turnover intentions since employees' feeling of psychological distress accentuates their low level of on-the-JEM (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, & Westman, Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018).

Second, job-embedded employees as a consequence of influences in the company may not necessarily be emotionally attached to the company and show satisfaction with their job (Crossley, Bennett, Jex, & Burnfield, Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007). Unlike JSAT, on-the-JEM is not constantly affective in nature (Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007). AOC represents workers' involvement in and emotional ties to the company, while on-the-JEM is not bounded with ties based on identification with the company or possession and achievement of the company's goals (Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007). Therefore, testing the mediation effect of on-the-JEM in the association between abusive supervision and propensity to quit is stronger than the mediation effects of the traditional attitudinal constructs such as AOC and JSAT is relevant and significant.

Third, we extend the interrelationships of abusive supervision, on-the-JEM, AOC, JSAT, and turnover intentions to the restaurant industry in Ghana, a sub-Saharan African country. Restaurants are important components of the hospitality industry. Despite the devastating effect of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry across the globe (Sanabria-Díaz, Quintana, & Araujo-Cabrera, Reference Sanabria-Díaz, Quintana and Araujo-Cabrera2021), statistics in 2020 reveals that restaurants, together with hotels in Ghana, have contributed about 640.9 million USD to the country's gross domestic product (Sasu, Reference Sasu2021). However, as is elsewhere, the hospitality industry in Ghana is characterized by high rate of employee turnover (Anthony, Mensah, & Amissah, Reference Anthony, Mensah and Amissah2021). Research also indicates that employee turnover highlights costs associated with the forfeiture of company knowledge and training newcomers (Robinson, Kralj, Solnet, Goh, & Callan, Reference Robinson, Kralj, Solnet, Goh and Callan2014). In short, we use data gathered from restaurant frontline employees in three waves in Ghana to gauge the previously mentioned linkages.

Literature review and hypotheses

Abusive supervision

One of the destructive supervisory practices in the hospitality and tourism context is abusive supervision (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Xu, Li and Kong2020). Employees are beset with antagonistic verbal and nonverbal behaviors when they work under abusive supervision (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Such behaviors do not include physical contact (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Supervisors' behaviors that are abusive may include public mockery and criticism and holding back important information (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Ma, Zhou, & Mu, Reference Ma, Zhou and Mu2021). This is a negative shock experienced by employees who have been working under abusive supervision. Hospitality employees exposed to sustained mistreatments from supervisors have been found to display various undesirable work outcomes such as reduced JSAT, elevated service sabotage, decreased work engagement, and greater silence behavior (Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah, & Ameza-Xemalordzo, Reference Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah and Ameza-Xemalordzo2022; Park & Kim, Reference Park and Kim2019). In their empirical piece, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Hsieh and Wang2020) found that abusive supervision exacerbated employee silence.

Affective commitment

Organizational commitment is designated by three dimensions: affective, continuance, and normative (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990). Continuance commitment highlights employees' perceptions of costs associated with leaving the company, while normative commitment denotes employees' sense of moral obligation to remain in the company (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990). Affectively committed employees are emotionally attached to, identified with, and involved in the organization (Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990). The present paper focuses on AOC because it explains significant variance in work outcomes more than continuance and normative organizational commitment (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002). Evidence demonstrates that AOC is a predictor of behavioral outcomes such as enhanced proactive customer service performance and customer orientation and decreased turnover intentions (Ribeiro, Duarte, & Fidalgo, Reference Ribeiro, Duarte and Fidalgo2020; Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021).

Job satisfaction

JSAT has been one of the most discussed variables in the hospitality and tourism literature since satisfied employees are noted of offering best quality services, which is critical for obtaining competitive advantage (Albashiti, Hamid, & Aboramadan, Reference Albashiti, Hamid and Aboramadan2021; Díaz-Carrión, Navajas-Romero, & Casas-Rosal, Reference Díaz-Carrión, Navajas-Romero and Casas-Rosal2020). Research indicates that employees with high JSAT contribute to desirable work-related consequences such as heightened job performance and lower quitting intentions (Albashiti, Hamid, & Aboramadan, Reference Albashiti, Hamid and Aboramadan2021; Koo, Yu, Chua, Lee, & Han, Reference Koo, Yu, Chua, Lee and Han2020). A recent study revealed that abusive supervision negatively influenced AOC through JSAT (Ampofo et al., Reference Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah and Ameza-Xemalordzo2022).

On-the-job embeddedness

JEM represents the combined factors that inspire employees to stay in their jobs (Zia et al., Reference Zia, Naveed, Bashir and Iqbal2022). On-the-JE and off-the-JE are the two components of JE (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004). On-the-JE considers factors within the company that keep employees in their job (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020). These include perks and social ties with supervisors and coworkers (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004). Off-the-JEM denotes influences outside the company (or residential community) that inform employees' decision to stay in their jobs (Park, Zhu, Doan, & Kim, Reference Park, Zhu, Doan and Kim2021). Examples of off-the-JEM include good weather and relationships with friends and family (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004). This paper selects on-the-JEM as the focal variable on the score that all the remaining variables (abusive supervision, turnover intentions, JSAT, and AOC) are influences within the company. It is also evident in literature that on-the-JEM is a stronger predictor of work outcomes than off-the-JE (e.g., Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004).

On-the-JEM comprises three sub-dimensions: ‘links’, ‘fit’, and ‘sacrifice’ (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). Fit denotes workers' personal values and career goals are compatible with those of the organization (Yang, Chen, Roy, & Mattila, Reference Yang, Chen, Roy and Mattila2020). Links relate to the quantity of formal or informal ties employees have within the company (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020). Sacrifice represents employees' perceived loss of benefits associated with their withdrawal from the company (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004; Park et al., Reference Park, Zhu, Doan and Kim2021). Employees who have more links, perceive a good company-fit, and anticipate greater benefits to forfeit are likely to embed in the company (Lee et al., 2014; Zhang, Fan, Deng, Lam, Hu, & Wang, Reference Zhang, Fan, Deng, Lam, Hu and Wang2019).

Kiazad, Seibert, and Kraimer (Reference Kiazad, Seibert and Kraimer2014) opine that resources that are associated with fit (e.g., job-relevant skills) and links (e.g., supervisor support) are instrumental value since they enhance employees' ability to obtain other resources in the company (e.g., promotion). Sacrifice-related resources (e.g., allowance, pay) have intrinsic value since they are desired ends in themselves and have little use in obtaining new organizational resources (Kiazad, Seibert, & Kraimer, Reference Kiazad, Seibert and Kraimer2014). The higher employees' level of embeddedness with the company, the greater the resources they have accrued in the company (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020; Huang, Cheng, Sun, Jiang, & Lin, Reference Huang, Cheng, Sun, Jiang and Lin2021). On-the-JEM has been found to explain significant variance in behavioral and motivational consequences such as task performance, service behaviors, and employee engagement (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004; Park et al., Reference Park, Zhu, Doan and Kim2021).

Turnover intention

Research evidences that turnover intention is an immediate antecedent of employee turnover (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Liu, McKay, Lee and Mitchell2012). Our paper concentrates on turnover intention, which is a significant problem in the global hospitality industry (e.g., Albashiti, Hamid, & Aboramadan, Reference Albashiti, Hamid and Aboramadan2021). Several predictors of turnover intentions have been identified in the hospitality literature which include psychological distress, employee-fit, workplace ostracism, and work values (Anasori, Bayighomog, De Vita, & Altinay, Reference Anasori, Bayighomog, De Vita and Altinay2021; Li, Song, Yang, & Huan, Reference Li, Song, Yang and Huan2022; Saleem, Rasheed, Malik, & Okumus, Reference Saleem, Rasheed, Malik and Okumus2021).

Hypotheses

Our paper utilizes conservation of resources (COR) theory to develop the hypotheses concerning abusive supervision which has a stronger effect on on-the-JEM than on AOC, JSAT, and quitting intentions. COR theory proposes that individuals put in significant efforts to obtain and preserve resources (e.g., social resources, energy) that are of personal value to them (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Individuals incur stress when there are threats to their resources or resources are actually lost/are not recouped after investment (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). COR theory posits that individuals with limited resources are more prone to resource loss and are less able to receive additional resources (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018).

According to COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), on-the-JEM develops as a consequence of the combination of resources. Social support is an important resource as it enables employees to gain other resources (Kiazad, Seibert, & Kraimer, Reference Kiazad, Seibert and Kraimer2014). Social support from a supervisor may include advice, mentorship, and relevant-job information. Because employees who work under abusive supervisors would not obtain adequate social support from their supervisors, they are unlikely to obtain more resources in the company such as higher pay and bonus. Under these conditions, employees who are abused by their supervisors are more likely to report reduced on-the-JEM than increased turnover intentions, decreased AOC, and lower JSAT. In addition, COR theory suggests that fewer resources expose individuals to resource loss (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Therefore, stress can lead to resource loss and diminish on-the-JEM.

Congruent with COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), workers are inspired to safeguard and keep their personally valued resources to refrain from experiencing stress which emanates from loss of resources. However, abusive supervisors exhaust the quantity of resources that individuals have in the workplace. In this case, such workers are more likely to be low on on-the-JEM than low on JSAT, turnover intentions, and AOC since they would be more prone to resource loss in the company. Individuals with fewer resources are unlikely to engage in activities that would lead to loss of the remaining resources. Because leaving a company is associated with potential loss of accumulated resources (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton and Holtom2004), employees with fewer work resources as a consequence of abusive supervision may prefer being low on on-the-JEM to developing an inclination to quit the company.

Empirical studies illustrated that abusive supervision had a negative association with JSAT (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021) and AOC (Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021). A recent systematic review by Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Xu, Li and Kong2020) and empirical studies (e.g., Moin, Wei, Khan, Ali, & Chang, Reference Moin, Wei, Khan, Ali and Chang2022; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Martinez, Van Hoof, Tews, Torres and Farfan2018) revealed that abusive supervision was positively associated with quitting intentions. Teng, Cheng, and Chen (Reference Teng, Cheng and Chen2021) showed that employees under abusive supervision had diminished JEM. However, no study has empirically compared the effect of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM to the effect of abusive supervision on AOC, JSAT, and turnover intentions so far. Filling this research gap is important because negative shocks (e.g., abusive supervision) that reduce employees' quantity of work resources may cause stress that has a stronger impact on employees' on-the-JEM than on their AOC, JSAT, and withdrawal intention (Holtom & Inderrieden, Reference Holtom and Inderrieden2006). In line with the above reasoning and findings, we hypothesize the following relationships:

Hypothesis 1: Abusive supervision has a more negative effect on on-the-JEM than AOC. Hypothesis 2: Abusive supervision has a more negative effect on on-the-JEM than JSAT. Hypothesis 3: The effect of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM is stronger than on turnover intentions.

JEM theory proposes that employees who are faced with negative work-related shocks (jarring events) would experience problems regarding links, fit, and sacrifice that bind them to the company (Holtom, Burton, & Crossley, Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). In our paper, we contend that abusive supervision, as a destructive leadership/supervisory practice, would be responsible for these problems and cause employees to develop propensity to leave the company. According to JEM theory, JEM is a key mediating mechanism between on-the-job and off-the-job factors and work-related consequences (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). Holtom, Burton, and Crossley (Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012) state, ‘In addition to the direct effects of JEM on discretionary behavior and organizational withdrawal, we believe that the construct may play an important mediating role in organizational life’ (p. 436). Employees who are plagued with abusive supervision would have weakened emotional bonds to the company and therefore display propensity to quit. As a negative work-related shock, abusive supervision is likely to erode quality connections between employees and the employer, impedes a good person-company fit, and makes employees forfeit the benefits within the company. In such an environment, employees would exhibit on-the-JEM at low levels, which in turn triggers their proclivity to quit. For instance, Holtom, Burton, and Crossley (Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012) found that work-related negative shocks influenced JEM deleteriously and JEM acted as a mediator between these shocks and various behavior outcomes (e.g., job search behavior).

Although prior studies have documented on on-the-JEM as a mediator in organizational life (e.g., Zia et al., Reference Zia, Naveed, Bashir and Iqbal2022), no study has compared on-the-JEM as a mediator to other mediating variables in the same linkage. Our study fills this research gap by comparing the impact of on-the-JEM as a mediator to the impact of JSAT and AOC as mediators in abusive supervision's relationship with turnover intentions. Stress which arises from resource loss or threat is more likely to impact on-the-JEM than JSAT and AOC (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018).

As propounded by COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), individuals with scarce resources are more defenseless to resource loss and less capable of acquiring new resources. Employees who are abusively treated by their supervisor would have insufficient work-related resources (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021). Under these circumstances, abused employees would be low on on-the-JEM and think about leaving the company. In addition, fewer resources would expose abused employees more to resource forfeiture in the company, which would lower their on-the-JEM. Finally, abused employees would be unable to gain other work resources to enhance their on-the-JEM.

Because employees low on on-the-JEM possess limited work resources, they are likely to be exposed to resource loss in the company which would lead to psychological distress (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fan, Deng, Lam, Hu and Wang2019). Employees who feel psychologically distressed are likely to develop the tendency to quit the company (Anasori et al., Reference Anasori, Bayighomog, De Vita and Altinay2021). On the other hand, employees receiving fewer resources from abusive supervisors are likely to feel psychologically distressed (Chi & Liang, Reference Chi and Liang2013). Under these conditions, such employees would be low on JSAT and AOC and subsequently display proclivity to leave the company (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Koo et al., Reference Koo, Yu, Chua, Lee and Han2020). However, we believe that employees' feelings of psychological distress would be greater when they are low on on-the-JEM than when they are low on JSAT and AOC because low on-the-JEM broadly epitomizes stress (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fan, Deng, Lam, Hu and Wang2019). Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4: The mediation impact of on-the-JEM in the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions is stronger than the mediation impact of JSAT. Hypothesis 5: The mediation impact of on-the-JEM in the relationship between abusive supervision and turnover intentions is stronger than the mediation impact of AOC.

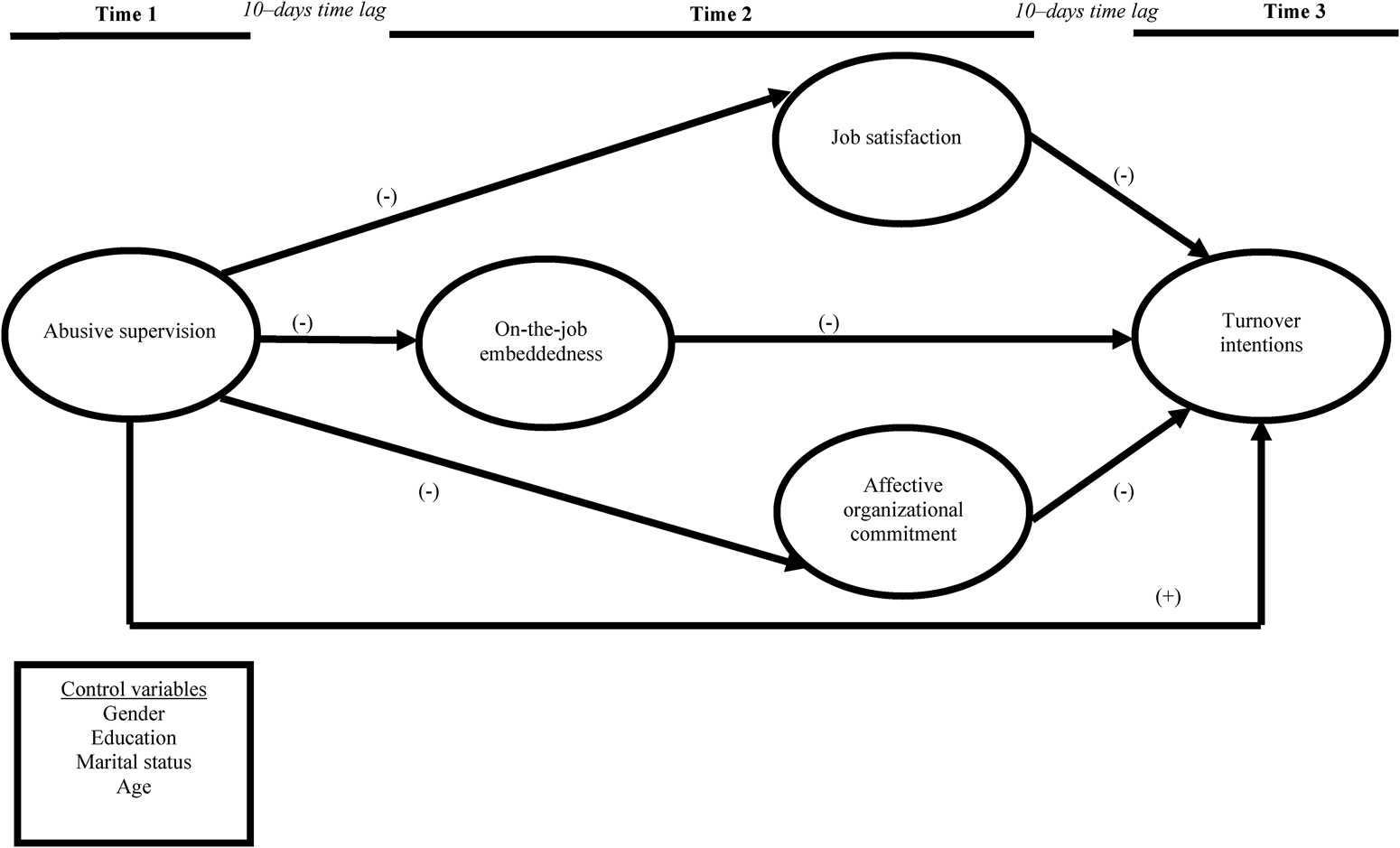

The research model guiding our study is depicted in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Research model.

Method

Sample and procedure

Data were obtained from frontline employees (i.e., waiters, waitresses, hosts, and hostesses) in 35 restaurants in Accra in Ghana. We selected the restaurant industry because it represents the fastest growing part of Ghana's local economy with an annual increasing rate of 20% (Boafo, Sarku, & Obodai, Reference Boafo, Sarku and Obodai2021). Because various international food brands like Chicken Inn, Pizza Inn, and Kentucky Fried Chicken have entered the restaurant industry in Ghana, the level of competitiveness in the industry has increased tremendously. However, like in several countries, restaurants in Ghana have a major problem of high rate of employee turnover which largely emanates from poor human resource practices (Ampofo & Karatepe, Reference Ampofo and Karatepe2022; Jerez Jerez, Melewar, & Foroudi, Reference Jerez Jerez, Melewar and Foroudi2021). Restaurants that are unable to keep talented employees may struggle to survive and remain relevant in a competitive industry (Chen & Qi, Reference Chen and Qi2022). High turnover rates are costly to restaurant companies (Jolly, Gordon, & Self, Reference Jolly, Gordon and Self2021). Abusive supervision is one of the common poor practices of leaders in Ghana's hospitality industry and has been attributed to the high degree of limited job offers in the country (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Ampofo et al., Reference Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah and Ameza-Xemalordzo2022).

In light of the judgmental sampling technique (Zhuang, Chen, Chang, Guan, & Huan, Reference Zhuang, Chen, Chang, Guan and Huan2020), we used at least two criteria for selecting such employees. First, frontline employees play a pivotal role in the provision of quality services and accomplishment of customer satisfaction (e.g., Ozturk, Karatepe, & Okumus, Reference Ozturk, Karatepe and Okumus2021). Second, they have frequent interactions with customers and spend time serving customers (e.g., Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020). Employees working in the back of the house were not included in the sample.

Prior to the commencement of main data gathering, a pretest study was conducted with 16 frontline employees in three restaurants regarding comprehensibility and legibility of the items. Each of these employees was granted personal interviews after completion of the survey. Consequently, the wording of the items was not changed.

The potential risk of common method variance was remedied by using various procedural approaches (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Specifically, consent was sought from managers of the selected restaurants. Administered surveys were placed in sealed envelopes. Employees were advised to personally return completed surveys in sealed envelopes. In addition, they were made aware that filling out the surveys was voluntary and could withdraw at any time. In our paper, three different surveys were employed to gather data through a 10-day time interval. Abusive supervision was operationalized at Time 1, while AOC, on-the-JEM, and JSAT were assessed at Time 2. Turnover intentions were assessed at Time 3. Items about respondents' profile were assessed at Time 1.

The administration of the surveys commenced in the first week in October 2020 and was brought to a close in the second week in December 2020. The Time 1 survey included 400 participants. These participants were again approached in Time 2. However, six employees voluntarily withdrew from the study for personal reasons. Hence, 394 employees participated in the Time 2 survey and completed and returned the questionnaires. In the final time of data collection, the Time 3 surveys were administered to all 394 Time 2 participants. Of this number, only one employee declined participation in the Time 3 survey, and this was attributed to private reasons. Accordingly, the Time 3 survey had 393 frontline employees. This represented 98.3% (393/400) response rate. In summary, 393 frontline employees partook in all three surveys. It is important to note that all returned surveys in each time were tracked using restaurant, location, number, or respondents' initial names.

One hundred and ninety-three participants (49%) were younger than 30 years, while 135 (34%) fell within the age category of 30–40. The rest were older than 40 years. The sample consisted of 236 (60%) females and 157 (40%) males. Eighty-nine (23%) participants held junior high school or O'level certificates, while 209 (53%) had senior high school certificates. The rest had 2-year college degrees or better. Forty-nine percent of the participants were married. The rest were single.

Instrumentation

We assessed all five variables (on-the-JEM, abusive supervision, JSAT, turnover intention, and AOC) utilizing items from previous empirical studies in the relevant literature. Specifically, on-the-JEM (α = .902) was operationalized with Crossley et al.'s (Reference Crossley, Bennett, Jex and Burnfield2007) seven items. Sample items are ‘I feel attached to this organization’ and ‘I simply could not leave the organization that I work for’. Turnover intention (α = .878) was assessed via two items from Begley and Czajka (Reference Begley and Czajka1993). An example item is ‘I often think about quitting my current job’. Abusive supervision (α = .942) was measured using six items from Harris, Harvey, and Kacmar (Reference Harris, Harvey and Kacmar2011). Example items are ‘My supervisor makes negative comments about me to others’ and ‘My supervisor puts me down in front of others’. JSAT (α = .932) was assessed via three items adopted from Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). Sample items include ‘All in all, I am satisfied with my job’ and ‘In general, I like working here’. AOC (α = .892) was operationalized via five items from Allen and Meyer (Reference Allen and Meyer1990). Example items include ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization’ and ‘I feel a “strong” sense of belonging to my organization.’

The abovementioned coefficient αs were >.70, delineating evidence of internal consistency reliability (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). Responses to items for all constructs were recorded on a 5-point scale (‘1 = strongly disagree’ to ‘5 = strongly agree’). Finally, we sought to control for possible demographic variables such as gender, education, marital status, and age by testing their effects on JSAT, AOC, on-the-JEM, and propensity to quit (e.g., Albashiti, Hamid, & Aboramadan, Reference Albashiti, Hamid and Aboramadan2021; Ozturk, Karatepe, & Okumus, Reference Ozturk, Karatepe and Okumus2021).

Data analysis

We employed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) via Analysis of Moment Structures version 25 to assess the psychometric properties of the measures (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). Structural equation modeling was performed to gauge the associations. Full mediation and partial mediation analyses were employed, and their fit statistics were compared to each other. The purpose was to determine the better-fitted model. The mediating effects were assessed via the Sobel and bootstrapping tests. A bootstrap sample of 5,000 was employed in the study. Furthermore, a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval was utilized. A mediating impact was considered significant when ‘lower bounds confidence interval’ (LBCI) and ‘upper bounds confidence interval’ (UBCI) did not exceed 0. The study utilized the following fit indices: ‘χ2/df, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)’ (e.g., Van Beurden, Van Veldhoven, & De Voorde, Reference Van Beurden, Van Veldhoven and De Voorde2021).

Results

Assessment of the measurement model

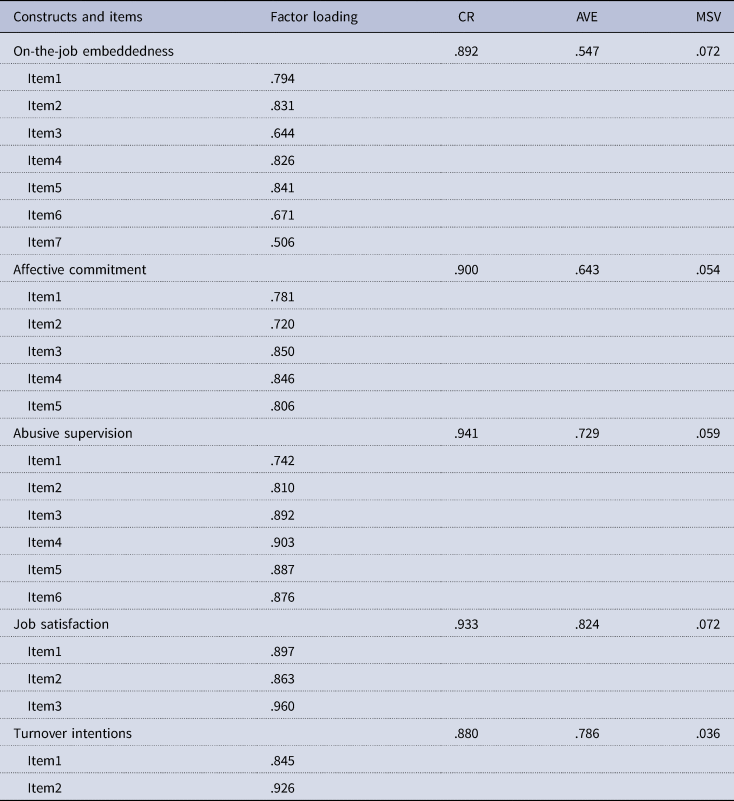

The findings from CFA were shown in Table 1. The measurement model fitted the data adequately (χ2 = 431.192, df = 207, χ2/df = 2.083; CFI = .964; TLI = .956; RMSEA = .053). Furthermore, convergent validity was verified since average variance extracted (AVEs) and standardized loadings were >.50 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). Discriminant validity was adequate since AVEs exceeded maximum shared variance (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). Composite reliabilities were >.60. This denoted evidence of further reliability of the measures (Ozturk, Karatepe, & Okumus, Reference Ozturk, Karatepe and Okumus2021).

Table 1. Confirmatory factor analysis

AVE, average variance extracted; MSV, maximum shared variance; CR, composite reliability.

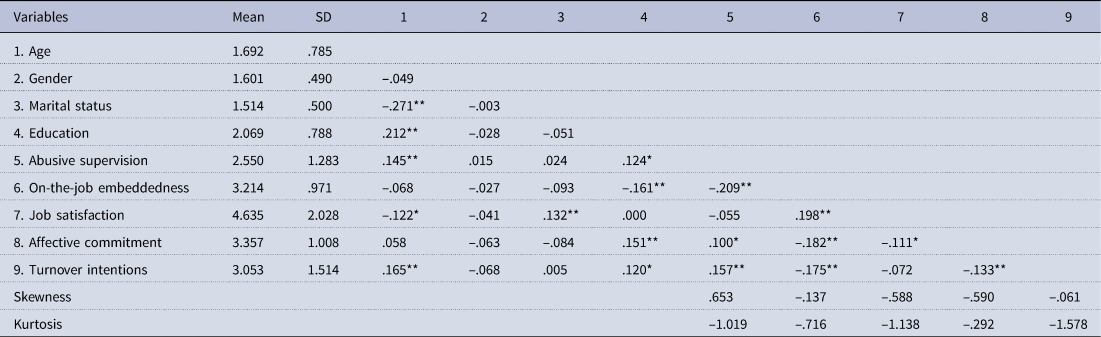

Table 2 presented the findings for summary statistics, linearity, and correlations. The findings demonstrated normal distribution for all the variables because skewness and kurtosis were less than 3.00 and 8.00, respectively (Kline, Reference Kline2011).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations

SD, standard deviation.

*p < .05; **p < .01 (two-tailed).

Assessment of hypotheses in the structural model

Table 3 presented the findings associated with the comparison of the partially-mediated model and the fully-mediated model. The partial mediation model (χ2 = 432.453, df = 267) had a better fit (Δχ2 = 10.716, p > .05, Δdf = 3) than the full mediation model (χ2 = 443.169, df = 270). Further, the findings illustrated that the fit statistics for the partial mediation model (CFI = .975; TLI = .969; RMSEA = .040) were better than the fit statistics for the full mediation model (CFI = .974; TLI = .968; RMSEA = .041). Therefore, the partial mediation model was utilized.

Table 3. Results: model comparison

CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

*p < .05.

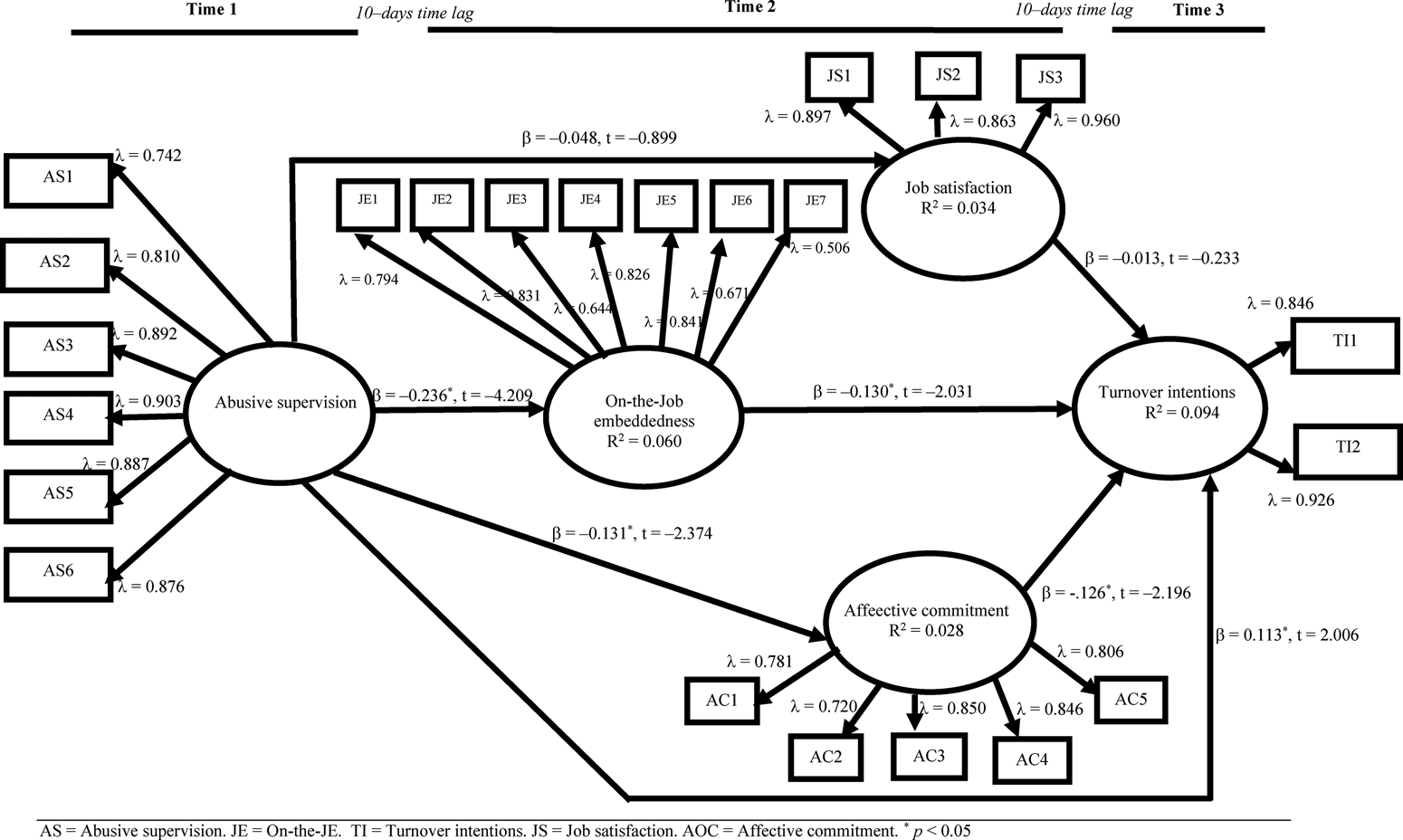

Figure 2 illustrated the findings for the direct path estimates. Abusive supervision had a stronger significant impact on on-the-JEM (β = ‒.236, t = ‒4.209) than on AOC (β = ‒.131, t = ‒2.374), JSAT (β = ‒.048, t = ‒.899), and turnover intentions (β = .113, t = 2.006), which confirmed hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, respectively. These results suggest that abusive supervision decreases on-the-JEM greater than it decreases AOC and JSAT and increases quitting intentions.

Fig. 2. Path estimates for the partial mediation model.

Table 4 showed the findings relating to mediation effects. The indirect effect from abusive supervision to turnover intentions (B = .048, LBCI = .017, UBCI = .100) was significant. The Sobel (Table 4) test results demonstrated that the mediation effect of on-the-JEM in the linkage between abusive supervision and turnover intentions (z = 2.028, p < .05) was significant, while the mediation impacts of JSAT (z = .223, p > .05) and AOC (z = 1.609, p > .05) were not significant. These findings verified hypotheses 4 and 5, respectively. The findings denote that abusive supervision influences quitting intentions via the mechanism of on-the-JEM better than via the mechanisms of JSAT (hypothesis 4) and AOC (hypothesis 5). The control variables were not significantly related to turnover intentions. The significance of the direct and indirect impacts did not change when the control variables were not included in the analysis.

Table 4. Results: Sobel test

* p < .05.

Discussion

Summary of findings

The deleterious impact of abusive supervision on AOC, proclivity to leave, and JSAT has been well-documented (e.g., Ampofo et al., Reference Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah and Ameza-Xemalordzo2022; Moin et al., Reference Moin, Wei, Khan, Ali and Chang2022; Teng, Cheng, & Chen, Reference Teng, Cheng and Chen2021). However, no study has compared the impact of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM to the impact of abusive supervision on JSAT, turnover intentions, and AOC. Filling in this gap is important because stress that results from resource loss or threat may have stronger impact on employees' on-the-JEM than on their turnover intentions, JSAT, and AOC. Thus, our paper contributed to the current literature by exploring whether the impact of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM was greater than on JSAT, AOC, and turnover intentions. In addition, our paper investigated whether the mediation impact of on-the-JEM in the linkage between abusive supervision and turnover intentions was stronger than the mediation impacts of JSAT and AOC. There are at least two observations that surface from the aforesaid results.

First, abusive supervision, as a negative work-related shock, erodes employees' interpersonal connections with others in the company, hinders their compatibility with the company, and makes employees develop a propensity to leave the company. Concordant with JEM theory, employees are likely to display quitting intentions when they are beset with shocks. The results concerning the impact of abusive supervision on JSAT, AOC, and quitting intentions are concordant with the works of Ampofo (Reference Ampofo2021), Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Martinez, Van Hoof, Tews, Torres and Farfan2018), and Zang, Liu, and Jiao (Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021). In this paper, we have found that the effect of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM is more than on traditional attitudinal variables such as JSAT and AOC. These findings are in consonance with COR theory that employees who receive constant rudeness, intimidation, and hostility from supervisors are likely to have depleted resources within the company (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Once resources are depleted, on-the-JEM would decrease. Because on-the-JEM is a consequence of work resources, employees would be highly embedded in a job when they have obtained several work resources (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001). Any shock that causes a negative impact on the quantity of resources that employees possess in a company has the tendency to have a greater impact on their level of on-the-JEM than on AOC and JSAT (Holtom & Inderrieden, Reference Holtom and Inderrieden2006). Specifically, the presence of abusive supervisory practices is more likely to influence on-the-JEM since employees would be denied a number of work resources from supervisors.

Second, the mediation effect of on-the-JEM in the linkage between abusive supervision and quitting intentions is stronger than the mediation effects of AOC and JSAT. These findings are in congruence with COR theory that individuals who lack adequate resources within the company are more prone to resource loss and less potent to obtain other resources (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018).

Individuals who work under supervisors who continuously demonstrate abusive behavioral tendencies are more likely to experience resource depletion, which might cause resource insufficiency (low on-the-JEM). In this case, employees would not only be more prone to resource forfeiture and but also be deficient in resource gains, which might increase their proclivity to quit the company. It seems that individuals with perceptions that their valued resources are defenseless and cannot be retained and utilized to foster resource acquisition are likely to leave their company (cf. Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). As supervisors via abusive behaviors help maximize employees' resource loss within the company, employees are likely to think about quitting since they would have limited resources to deal with threats to resource loss or actual forfeiture of future resources. Hence, employees who are low on on-the-JEM would likely consider intentions to quit as a better option when they find themselves under abusive supervisors. It appears that their continuous stay in a hostile work milieu might cause them a more psychological distress.

Theoretical implications

The aforesaid findings contribute to the relevant literature in the following ways. Specifically, in this paper, we considered abusive supervision as one of the negative work-related shocks. Employees who are constantly abused by supervisors display undesirable work-related outcomes such as JSAT, AOC, and turnover intentions (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2021; Moin et al., Reference Moin, Wei, Khan, Ali and Chang2022; Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021). There is only one empirical study that has explored the indirect impact of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM through perceived organizational support (Dirican & Erdil, Reference Dirican and Erdil2022). Likewise, there are only two empirical pieces, which have examined the linkage between abusive supervision and AOC so far (Guan & Hsu, Reference Guan and Hsu2020; Zang, Liu, & Jiao, Reference Zang, Liu and Jiao2021). However, the current literature delineates no evidence that has examined on-the-JEM, JSAT, AOC, and turnover intentions simultaneously as the consequences of abusive supervision. We reported that abusive supervision had a more negative impact on on-the-JEM than on traditional attitudinal variables such as JSAT and AOC. We also reported that the impact of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM was stronger than on propensity to quit.

The findings enhance current knowledge by demonstrating that the mediation impact of on-the-JEM in the association between abusive supervision and turnover intentions is stronger than the mediation impacts of JSAT and AOC. These findings highlight the critical role of on-the-JEM as a mediator between abusive supervision and proclivity to leave. As claimed by Holtom, Burton, and Crossley (Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012), JEM would ‘…play an important mediating role in organizational life’ (p. 436). In short, these findings are significant since no empirical piece has compared the mediation effects of on-the-JEM in the relationships given above.

Our study extends the abusive supervision and on-the-JEM research to the restaurant industry in Ghana, which is underrepresented in the hospitality and tourism research (Ampofo, Reference Ampofo2020, Reference Ampofo2021). This is also obvious in Yu et al.'s (Reference Yu, Xu, Li and Kong2020) systematic review and Mackey et al.'s (Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017) meta-analytic studies.

Management implications

Strategies in reducing hostility and intimidation of supervisors in the workplace can help retain talented employees and enhance on-the-JEM in restaurants. First, in Ghana, people who are perceived to be in higher positions and authorities escape punishment when they float rules and laws. To minimize abusive supervision, managers should practice an effective punishment system regarding abusive supervision that would be fully implemented without fear or favor (cf. Ampofo et al., Reference Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah and Ameza-Xemalordzo2022). Once these are implemented effectively, they serve as a deterrent for future occurrence. Second, restaurant managers should understand that the fear of becoming unemployed for a longer time when they forfeit their current jobs would keep employees who are abused by their supervisors silent. Under this circumstance, managers of restaurants should promise job security to high-performing employees who work under abusive supervisors.

Third, management of restaurants should arrange continuous training programs to teach the detrimental effects of destructive leadership practices on employee and organizational outcomes to supervisors and the candidates for supervisory positions (cf. Peltokorpi & Ramaswami, Reference Peltokorpi and Ramaswami2021). In these programs, clear expectations about positive supervisor behaviors should be highlighted, and specific case studies should be used to teach these positive behaviors (cf. Park & Kim, Reference Park and Kim2019). Despite good intentions of management, if there are still some supervisors practicing abusive supervision, letting them leave the company would be more beneficial instead of trying to keep them in the company.

Lastly, management of restaurants should hire the right individuals for frontline service jobs and/or supervisory positions. To achieve this, strict selection practices should be in place. For example, management can take advantage of experiential exercises about unethical acts targeted at subordinates during the selection process since abusive supervision triggers the likelihood of unethical acts in daily work life (cf. Xu et al., Reference Xu, Martinez, Van Hoof, Tews, Torres and Farfan2018).

Limitations and future research

Despite the promising findings reported above, the present paper has several limitations. First, this paper's sample was limited to only workers who offered frontline services in restaurants. However, employees in different positions can be abused by their supervisors in the hospitality industry. Future research should include employees who occupy other positions (i.e., back-of the house) in different types of restaurants. Second, our paper tested the effect of abusive supervision on employees' on-the-JEM, JSAT, turnover intentions, and AOC. However, it is not only supervisors who can abuse employees in the company. Coworkers can also abuse the focal employee such that the employee may forfeit valued resources in the company (Tews, Michel, & Stafford, Reference Tews, Michel and Stafford2019). Future studies should test the impact of abusive coworker treatment on JSAT, AOC, on-the-JEM, and propensity to leave.

Third, employing time-lagged data helped minimize the risk of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). It would be more useful in future research to use managers and coworkers' assessment of workers' AOC, JSAT, turnover intentions, and on-the-JEM. Fourth, the utilization of temporal separation through a time lag of 10 days between the variables did not provide enough evidence of causality. In future research, these relationships should be tested via a longer period of time.

Fifth, abusive supervision has been linked to other outcomes like job performance (Srikanth, Thakur, & Dust, Reference Srikanth, Thakur and Dust2022), innovative work behavior (Khan, Moin, Khan, & Zhang, Reference Khan, Moin, Khan and Zhang2022), organizational citizenship behavior (Lyu, Zhu, Zhong, & Hu, Reference Lyu, Zhu, Zhong and Hu2016), and knowledge sharing (Islam, Ahmad, Kaleem, & Mahmood, Reference Islam, Ahmad, Kaleem and Mahmood2020). There would be a relevant contribution to the literature when future investigation focuses on gauging the impact of abusive supervision on on-the-JEM and the aforesaid outcomes.

Sixth, it is empirically evident that employees under abusive supervision are disengaged at work and show greater proclivity to leave the company (Ampofo et al., 2021; Ampofo & Karatepe, Reference Ampofo and Karatepe2022). In addition, occupational embeddedness emphasizes the totality of influences (links, fit, and sacrifices) that keep employees in their occupation (Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2007). Employees who are under abusive supervision may be low on occupational embeddedness because the poor relationship they have with their supervisor may lead to resource depletion (Ampofo et al., Reference Ampofo, Ampofo, Nkrumah and Ameza-Xemalordzo2022). Employees who are low on occupational embeddedness have been found to demonstrate higher quitting intentions (Yang, Guo, Wang, & Li, Reference Yang, Guo, Wang and Li2019). Future research can enhance the knowledge base in the current literature by testing whether abusive supervision has a stronger impact on proclivity to leave through on-the-JEM than through work engagement and occupational embeddedness.

Seventh, our study used data collected from the same types of restaurants. In future research, gathering data from different types of restaurants would enable the researchers to conduct a multi-level analysis at the organizational level. Lastly, abusive supervision is one of the destructive behaviors of leaders in companies. In future studies, testing the effects of other destructive leadership styles such as despotic and narcissistic leadership on JSAT, on-the-JEM, AOC, and proclivity to leave would be a significant addition to the relevant literature.

Conclusion

Our paper set out to advance the pertinent literature by contending that abusive supervision had a more negative impact on on-the JEM than on JSAT and AOC. In this paper, we proposed that the impact of abusive supervision on on-the JEM was stronger than on proclivity to leave. We also posited that the indirect impact of abusive supervision on proclivity to leave via on-the-JEM was stronger when compared with the indirect impact of abusive supervision on proclivity to leave via JSAT or AOC. The hypotheses proposed in the current study were confirmed by data collected from employees in restaurants in Ghana. Our study provided useful insights for both researchers and managers by comparing the findings about on-the-JEM with the ones about traditional attitudinal variables.

Acknowledgment

Data used in this study came from part of a larger project.

Conflict of interest

None.