Introduction

Public employment services (PES) is a core type of active labour market policy (ALMP). The PES facilitate job matching processes and is arguably a nexus in most labour market policy systems due to its role as implementer of other types of ALMPs (King & Rothstein, Reference King and Rothstein1993; Mosley, Keller, & Speckesser, Reference Mosley, Keller and Speckesser1998; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1985). Since the PES have important mediating effects on other types of programmes, it may be considered essential for well-functioning labour market policy. However, the activitities of the PES are multidimensional. The PES provide services to the unemployed in form of advice and allocation into other labour market programmes, but also have coercive elements as the PES often are responsible for monitoring unemployment benefit claimants and imposing sanctions in cases of non-compliance. This duality between support and coercion has important implications, especially when considering analysis of the driving forces behind policy change and the resources devoted to PES.

In terms of partisan politics, interventions that have straightforward redistributive consequences, eg., training programmes that enhance human capital and employment chances among participants, lend themselves more easily to theorize through the lens of political preferences (Nelson, Reference Nelson2013). However, it has proven difficult to disentangle ‘carrots’ (services) from ‘sticks’ (sanctions and monitoring) when tracking the development of resources devoted to PES. Hypotheses related to partisan politics are therefore ambivalent and most studies that analyse political determinants of more fine-grained categories of ALMP omit PES altogether, or refrain from theorizing partisan effects on PES spending (eg. Cronert, Reference Cronert2019; Nelson, Reference Nelson2013; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2013). Concurrently, the literature on activation and the so-called ‘activation turn’ have argued that labour market policy is converging. In relation to PES, countries have been argued to—irrespective of ideological orientation—alter the orientations of the PES to emphasize the ‘sticks’ of activation, ie., increased monitoring of benefit claimants and job-seekers rather than providing the service of finding the best job match or intervention (Eichhorst & Konle-Seidl, Reference Eichhorst, Konle-Seidl, Eichhorst, Kaufmann and Konle-Seidl2008; Moreira & Lødemel, Reference Moreira, Lødemel, Lødemel and Moreira2014; Weishaupt, Reference Weishaupt2010). Unemployment benefits have been subject for similar and related ‘demanding’ reforms, with stricter benefit eligibility criteria and job-search requirements (Clasen & Clegg, Reference Clasen, Clegg, Clasen and Siegel2007; Knotz, Reference Knotz2018; Nelson, Reference Nelson2013; Weishaupt, Reference Weishaupt2011). While the development towards activation partly relates to changes in how the deservingness of the unemployed are perceived (eg. Clasen & Clegg, Reference Clasen and Clegg2003; Schumacher, Vis, & Van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher, Vis and Van Kersbergen2013; Van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000), a key rationale behind stricter conditionality and sanctions of benefits have been to reduce costs of social protection in face of austerity (Bengtsson, de la Porte, & Jacobsson, Reference Bengtsson, de la Porte and Jacobsson2017; Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Knotz, Reference Knotz2019). While some studies indicate that monitoring can be a cost-effective option (Boone et al., Reference Boone, Fredriksson, Holmlund and van Ours2007; Raffass, Reference Raffass2017), others argue that expanding systems of monitoring and sanctions can be associated with substantial costs (Eichhorst & Konle-Seidl, Reference Eichhorst, Konle-Seidl, Eichhorst, Kaufmann and Konle-Seidl2008, p. 427; Watts & Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018, p. 9). Although recent comparative studies show that partisan politics seems to be unrelated to the development of ‘demanding’ activation as such (Knotz, Reference Knotz2019), whether increased conditionality contributes to reduced or increased expenditures on PES is still unclear. If the development towards more ‘demanding’ activation take precedence over political preferences, it also suggests that in order to better understand the role of partisan politics, the analysis of resources devoted to PES should incorporate activation as well.

The purpose of this study is hence to explore determinants of PES spending, focussing particularly on partisan politics and activation. Based on the discussion above, two questions can be posed. First, is partisan politics related to resources devoted to PES once we account for the increase of ‘demanding’ activation in many countries? Second, the increase of activation as such associated with spending on PES? In terms of partisan politics, I distinguish between left, secular centre-right and confessional parties, where the latter refer, mostly, to the European Christian democratic parties that in important respects differ from secular centre-right parties in, eg., preferences for labour market intervention (eg. Kalyvas & Van Kersbergen, Reference Kalyvas and Van Kersbergen2010; Korpi & Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme2003; Nelson, Reference Nelson2013). In effort to disentangle services from sanctions in the activities of the PES, I utilize new data on sanctions and conditions in unemployment insurance (Knotz & Nelson, Reference Knotz and Nelson2018), thus enabling analysis of ‘demanding’ activation as well as partisan politics. The study analyses the period 1985–2011 and includes 16 OECD countries; Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany (West Germany before 1991), Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. The first section provides a discussion of the PES and potential links between partisan politics, activating policies and PES spending. Data and methodological considerations are then discussed, focusing particularly on the time-series methodology of error correction models. The penultimate section presents the empirical results, which is followed by a concluding discussion.

Public employment services expenditure

The PES consists of a heterogeneous set of policies. Broadly speaking, five components or responsibilities can be distinguished: Job brokerage to facilitate matches between supply and demand; provision of labour market information to employers and job-seekers by collecting data on job vacancies and potential applicants; allocation and implementation of ALMP; administration of unemployment benefits; and management and coordination of labour migration (OECD/IDB/WAPES, 2016). While theorizing effects related to partisan politics or ‘activation’ may be considered fairly straightforward for each separate component, a consistent problem for country-comparative studies is that the resources devoted to PES have historically not been available with respect to separate areas of responsibility, but only in terms of total resources. The pitfalls of analysing total government spending has been noted in relation to ALMP and social policy more generally (Clasen, Clegg, & Goerne, Reference Clasen, Clegg and Goerne2016; Siegel, Reference Siegel, Clasen and Siegel2007), but can be considered even more problematic in relation to PES. Even though increased resources to the PES are argued to be ‘open-ended’, ie., more resources equalling more impact on unemployment (Thuy, Hansen, & Price, Reference Thuy, Hansen and Price2001, p. 29), it is difficult to determine what high or low spending on PES means in terms of ‘sticks’ and ‘carrots’. This inherent ambiguity is the prime reason for refraining from partisan hypotheses (Nelson, Reference Nelson2013; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2013), but also plays a role in relation to activation, as it is difficult to determine if the observed increase in ‘demanding’ activation is related to costs for the key institution that implements activation policies, ie., the PES. The following sections will delineate some provisional expectations concerning the potential relationships that activation and partisan politics may have to PES resources.

Activation and benefit conditionality

The turn to activation has been a pervasive topic in the social policy research of recent decades. Although it is important to note that activation may be ‘enabling’ when considering expansion of ALMPs such as training schemes or the placement services and job-search assistance of the PES, a great deal of research has focused on the increase of ‘sticks’ or ‘demanding’ aspects of activation and the consequences of this development for unemployed and other marginalized groups. In this regard, many countries have come to emphasize ‘workfare’ or ‘making work pay’, ie., pushing unemployed or social assistance beneficiaries to take the first available job (Lødemel, Reference Lødemel and Gallie2004; Moreira & Lødemel, Reference Moreira, Lødemel, Lødemel and Moreira2014; Rueda, Reference Rueda2015; Van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2004). While increases in ‘demanding’ activation can be traced in many areas of social protection (Clasen & Clegg, Reference Clasen and Clegg2006, Reference Clasen and Clegg2011), this study focusses on two aspects of benefit conditionality related to unemployment insurance benefits (Knotz, Reference Knotz2018).

A key justification for ‘demanding’ activation is cost-containment. With respect to unemployment insurance, countries thus impose stricter conditions to receive benefits, and stricter sanctions, ie., reduced or rescinded benefits, when the unemployed fails to comply to, eg., job-search requirements, in effort to reduce costs during periods of high unemployment (Bengtsson, de la Porte, & Jacobsson, Reference Bengtsson, de la Porte and Jacobsson2017; Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Knotz, Reference Knotz2019; Rueda, Reference Rueda2015).

Since fewer individuals are eligible and receiving benefits, it is reasonable to argue that stricter conditions and sanctions may reduce spending on unemployment insurance. However, stricter conditionality may have varying effects on spending associated with different ALMPs. Some studies argue that monitoring benefit claimants and imposing sanctions for non-compliance can be a cost-effective alternative compared to expanding more expensive forms of ALMP, eg., training programmes (Boone et al., Reference Boone, Fredriksson, Holmlund and van Ours2007; Raffass, Reference Raffass2017). However, for the PES, which are responsible for benefit administration, expanding systems of monitoring can be associated with substantial costs, both with respect to building and maintaining administrative systems and with respect to staff time-management, especially in cases where monitoring is added on top of existing tasks (Eichhorst & Konle-Seidl, Reference Eichhorst, Konle-Seidl, Eichhorst, Kaufmann and Konle-Seidl2008, p. 427; Watts & Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018, pp. 104–107). In terms of restricting access to benefits, ie., changing conditions or eligibility criteria, the logic is similar. Restricting access may reduce spending on passive benefits and categories of ‘enabling’ ALMPs, but it is likely that curbing benefit rights is associated with increased costs for the PES, since systems of assessing the individual right to benefit may be associated with considerable costs in a similar way to that of systems of monitoring and sanctions.

Partisan politics and labour market policy

The role of partisan politics for the development of labour market policy is often reduced to the proclivity of using government intervention along the left–right continuum. Expansive ALMPs are hence typically denoted ‘leftist’, whereas the approach of deregulation and reliance on the market is signified as ‘rightist’ (Nelson, Reference Nelson2013). As recent studies have shown, this is an oversimplification of political preferences that are more nuanced when considering the wider range of ALMP (Nelson, Reference Nelson2013; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2013). The oversimplification is arguably particularly misleading in relation to the PES, where either ‘sticks’ or ‘carrots’ can be more salient. Since analysis of the relationship between partisan politics and expansion or retrenchment of ALMP seldom goes beyond the left–right scale, preferences for government intervention in the labour market among other political parties tend to be overlooked.Footnote 1

Confessional parties have, eg., been shown to pursue egalitarian social policies in competition with left parties during welfare state expansion, and to take intermediate positions between left and secular centrist-right parties in cutting back major social insurance programmes during the era of retrenchment (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Korpi & Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme2003; Montanari & Nelson, Reference Montanari and Nelson2013; Van Kersbergen, Reference Van Kersbergen1995). With respect to labour market policy, however, confessional parties do not seem to support comprehensive strategies or programmes (Hicks & Kenworthy, Reference Hicks and Kenworthy1998; Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001, pp. 185–186; Van Kersbergen, Reference Van Kersbergen, Van Kersbergen and Manow2009, p. 135; Van Kersbergen & Hemerijck, Reference Van Kersbergen, Hemerijck, Bauld, Ellison and Powell2009). The lack of support for labour market policies emanates from several sources, but may be traced explicitly to principles of subsidiarity. Confessional parties thus have a wariness for government interventions, but not necessarily from a laissez-faire view of the labour market. Rather, confessional parties tend to view employment policy as a responsibility of the social partners, not the government (Klitgaard, Schumacher, & Soentken, Reference Klitgaard, Schumacher and Soentken2015; Van Kersbergen, Reference Van Kersbergen1995, pp. 174–191) and confessional parties consistently downplay active policies, instead utilizing, eg., labour-shedding/early retirement to reduce unemployment (eg., Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen and Esping-Andersen1996), and focus on the provision of cash benefits rather than provision of services towards the unemployed (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001). The discussion thus indicates that confessional parties are less likely to be associated with higher levels of PES spending.

In a similar vein, left parties are often associated with social investment and market interventions that reduce unemployment, making left parties likely to spend considerable resources on ALMP (Boix, Reference Boix1998; Huo, Nelson, & Stephens, Reference Huo, Nelson and Stephens2008; Nikolai, Reference Nikolai, Morel, Palier and Palme2012; van Vliet & Koster, Reference van Vliet and Koster2011). However, some scholars have argued that left parties are less inclined to support ALMPs (Rueda, Reference Rueda2006, Reference Rueda2007; Tepe & Vanhuysse, Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2013; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2013). This counter-argument is based on the theory of insider-outsider cleavages, where left parties favour insiders of labour markets rather than promoting policies for outsiders, ie. the unemployed and those outside the labour force. While the latter stance may be an indication that political preferences are less clear-cut in relation to PES, it should be noted the majority of studies tend to indicate that left parties support active policies (see Nelson, Reference Nelson2013). Others have shown that the insider-outsider cleavages have contradictory impacts on the preferences of left parties that are contingent on institutional contexts (Fossati, Reference Fossati2018a). There is also reason to believe that left parties devote resources to PES in light of the long history of ALMP as a distinctly social democratic policy strategy. For instance, in the Nordic welfare states, the organization and execution of ALMP hinged, to a large degree, on well-functioning PES (King & Rothstein, Reference King and Rothstein1993; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1985; Weishaupt, Reference Weishaupt2011). Arguably, the prime function of PES as a way of reducing unemployment through services and allocation of unemployed into other labour market programmes indicate that left parties can be expected to be associated with higher PES spending. This assumption is bolstered by the fact that left parties are more likely to be punished electorally by high unemployment levels and economic crises, which creates incentives to pursue policies aiming to reduce unemployment (Lindvall, Reference Lindvall2014; Powell & Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993).

Secular centrist-right parties, lastly, are usually thought to be cautious of using labour market interventions and instead trust the market to counter unemployment. As such, centrist-right parties are generally assumed to block ALMPs. Instead, the focus is on creating work-incentives by lowering unemployment benefit levels and deregulating labour markets to achieve more flexibility (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010; Bradley & Stephens, Reference Bradley and Stephens2007; Furåker, Reference Furåker1997; Nelson, Reference Nelson2013). This argument, however, neglects that PES is a type of labour market policy that facilitates labour market processes, where the PES, eg., help employers to post vacancies as well as providing support for applicants to fill these vacancies. As stressed above, PES can also be combined with strong work incentives, which is often the case in countries where centre-right parties dominates (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2010). Hence, while centre-right parties often promote market solutions (Klitgaard, Schumacher, & Soentken, Reference Klitgaard, Schumacher and Soentken2015), there is a reason to believe that centrist-right parties could support the ‘enabling’ aspects of the PES, especially in combination with ‘demanding’ activation.

The relationship between partisan politics and benefit conditionality

The discussions above argue that ‘demanding’ activation may increase PES spending, and that political parties have different preferences in relation to the ‘enabling’ part of the PES, where left and secular centre-right parties are likely to spend more on PES compared to confessional parties. Since partisan politics and ‘demanding’ activation have yet to be analysed simultanously, it is difficult to predict the more salient factor in relation to the development of the PES. However, while the convergence of benefit conditionality across countries has mostly been attributed to declining economic conditions (Knotz, Reference Knotz2019), there is also a reason to believe that the relationship that partisanship may have to PES is conditional on the particular forms and extent of activation policies in a given country. This has partly been explored in relation to voters’ preferences, where voters in more ‘enabling’ countries, eg., Denmark, are less supportive of stricter activation policies (Fossati, Reference Fossati2018b).

In this regard, preferences among political parties with respect to unemployment insurance is relevant to consider. Left parties are, eg., typically associated with generous unemployment insurance (Huo, Nelson, & Stephens, Reference Huo, Nelson and Stephens2008; Scruggs & Allan, Reference Scruggs and Allan2004). However, to be able to retain generous benefits and promote employment during periods when costs of social protection must be constrained, left parties may focus on increasing PES spending particularly in contexts where benefit sanctions are strict. Individuals thus receive generous benefits and support through the PES, but are subject to stricter sanctions when failing to comply to regulations. Secular-centrist right parties are also likely to promote the enabling aspects of PES, but may do so under different circumstances. Since secular-centrist right have traditionally not been interested in extending rights or generosity of unemployment benefits (Scruggs & Allan, Reference Scruggs and Allan2004), they may spend more on PES in contexts where conditions to receive benefits are stricter. That is, when work-incentives are high due to curbed access, centre-right parties promote the enabling aspects of the PES rather than sanctioning those already unemployed. Thus, the resources that political parties devote to PES are contingent on the forms and extent of ‘demanding activation’.

Data

The dependent variable in this study is public employment services expenditure, which is publicly available from 1985 in the OECD Social Expenditure database (OECD, 2015b). The exact content included in expenditure varies somewhat between countries, but typically includes placement, counselling and vocational guidance. In addition, administration costs of labour market agencies as well as other labour market programmes may be included. From 1998, the spending measure is further divided in benefit administration and placement services, which would be preferred as it more closely conform to ‘enabling’ and ‘demanding’ aspects of the PES, but is not utilized since the number of years with more detailed data is lower than recommended in time-series analysis.

There are various ways of measuring spending, where some studies, eg., use the total spending as a percentage of GDP. In this study, expenditure on PES is defined as spending in U.S. dollar purchasing power parities (PPP) per unemployed, which take effort or ‘intensity’ into account (Bassanini & Duval, Reference Bassanini and Duval2006; van Vliet & Koster, Reference van Vliet and Koster2011). As a sensitivity test, the models below have been estimated with PES spending as a percentage of GDP, which is discussed further below.

The strength of political partisanship is measured as party shares of cabinets collected from the Political Data Yearbook (European Journal of Political Research, 2014) and extends data on political partisanship from Korpi and Palme (Reference Korpi and Palme2003). Cabinet shares have been calculated as the number of ministerial portfolios held by left parties, confessional parties and secular centrist-right parties, respectively, divided by the total cabinet size and weighted for cabinet changes during each observation year.Footnote 2 In the few instances that green or right-wing populist parties have had cabinet seats, they have been categorized as secular centrist-right parties since their scope of influence can be assumed limited with respect to the period and countries in this study. Although cabinet share is the most common measure of partisanship, some studies have used parliamentary share instead (eg. Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2013). Using parliamentary shares might capture long-term ideological shifts, but the focus on policy change makes the use of cabinet shares more reasonable. Longevity or cumulative incumbency of parties has also been suggested, but is arguably more relevant when analysing welfare state programmes with long maturation periods, such as pension schemes (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2014).

Data regarding benefit conditionality is collected from ‘The Comparative Conditions and Sanctions Dataset’ (Knotz & Nelson, Reference Knotz and Nelson2018). Two composite measures are available: Strictness of sanctions and strictness of benefit conditions. These are calculated as the summed scores of several component indicators, eg., job-search requirements in relation to conditions, and consequences of the first refusal of an offer of employment in relation to sanctions. The summed scores have then been divided by the theoretical maximum to reach an overall score varying between 0 (very lenient) and 1 (very strict). More detailed information regarding the construction of the indicators is available in Knotz (Reference Knotz2018, Reference Knotz2019).

In addition to partisan politics and benefit conditionality, there are numerous structural factors that have been suggested to be relevant for labour market policy development. Among them are unemployment, deindustrialization, budget deficits, economic growth, macro-corporatism and employment protection legislation (eg. Huo, Nelson, & Stephens, Reference Huo, Nelson and Stephens2008; Nelson, Reference Nelson2013; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2013). Of these, unemployment stands out as a key factor as it constitutes the raison d’être for labour market policy. For unemployment, civilian unemployment rates are used. Deindustrialization is measured as the share of the labour force active in the service sector. Data on coordination or macro-corporatism is from Visser (Reference Visser2013) and measured by centralization of wage bargaining along a five-point scale. The annually adjusted budget deficit is measured as percentage of GDP. In addition to these, GDP per capita (in log form) is also included as a control variable. Except for cabinet composition, conditionality and wage coordination, all independent variables are from the OECD Main Economic Indicators and Social Expenditure databases (OECD, 2015a, 2015b).

Methods

This study uses error correction models (ECM) to analyse how various determinants are related to PES spending. Dynamic regression models, like ECM, builds on the idea that there are both short-term effects and long-term associations between different time-series. Sudden shocks to the system can be felt immediately, but are also absorbed over time with a more or less steady return to equilibrium. An advantage of ECMs is the opportunity to specify a dynamic model where short- and long-term effects, defined in differences and levels respectively, are separated and estimated simultaneously. Such dynamics are increasingly being analysed in studies of welfare state development, and are theoretically appealing since determinants may influence spending both immediately and over the long-term. A general bivariate ECM model can be written as:

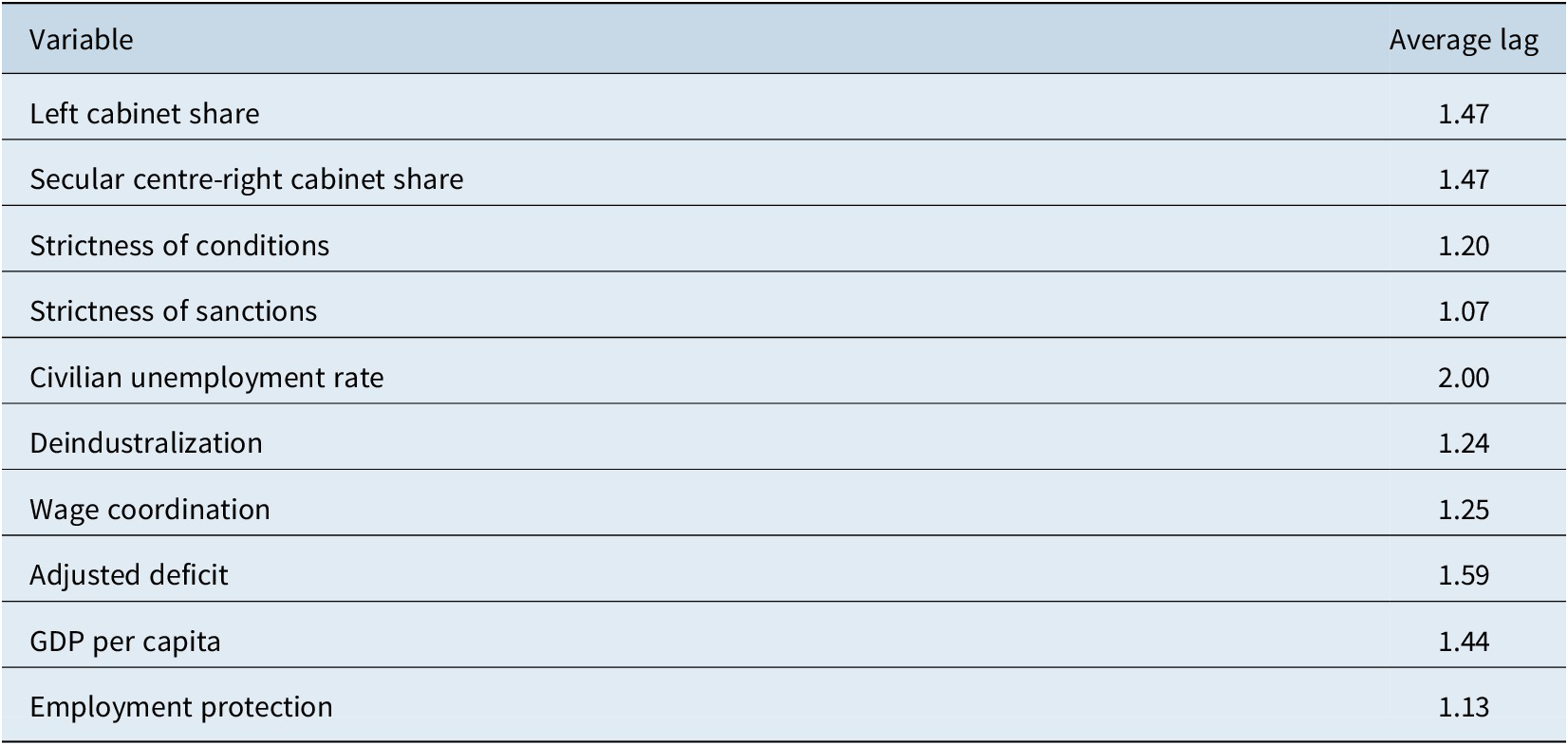

In Equation (1), the estimated coefficient of the lagged level of Y, or β0, is the error correction coefficient. If there is an error correcting mechanism, β0 should be negative and statistically significant (De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008). β1 captures immediate or short-term effects of Xi at time t, while β2 captures the effects on Yi of a one-unit increase in Xi. This term is lagged 1 year, which lessens problems of reverse causality, which could otherwise be a problematic issue, especially when including labour market policies and unemployment in the same model (Bassanini & Duval, Reference Bassanini and Duval2009). If there is reason to believe that variables should be lagged with more than 1 year, eg. due to cyclically recurring events, the number of lags can be determined using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Doing so indicated 1-year lags to be appropriate for most variables. There were some indications that the lag should be 2 years for unemployment, but the main results are unaffected regardless of lag choice. The average lags are available in the Appendix Table A1.

The specified model also provides a straightforward way to calculate the total long-term effect of a one-unit increase in X i, which in most instances is more interesting when a long-term relationship is present. This effect is commonly called the ‘long-run multiplier’ (LRM), since it depends on the size of the error correction coefficient. In ECM, the LRM is equal to −(β2 /β0 ). It is thus the total effect of a one-unit increase in Xi , distributed beyond t + 1, at the rate determined by the error correction coefficient.

An advantage of the ECM approach is that it reduces many of the problems otherwise common in time-series analysis. However, some issues are still important to take into consideration. In the ECM framework, all the included time-series have to be either stationary or non-stationary (De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008; Keele, Linn, & Webb, Reference Keele, Linn and Webb2016), which is determined using unit-root tests. These are available in the Appendix Table A2. Modified Wald tests and Pesaran’s test for cross-sectional independence, respectively, indicate that panels are both dependent and correlated. Standard errors that correct for both heteroscedasticity and contemporaneous correlation, as suggested by Beck and Katz (Reference Beck and Katz1995), are therefore used. Wooldridge tests for autocorrelation in panel data indicates autocorrelation for all time-series when these are expressed in levels, but not when expressed in differences (see Drukker, Reference Drukker2003). I apply panel-specific autocorrelation since the remaining variables are estimated both in terms of change and levels. Finally, multicollinearity can produce spurious results if the independent variables of interest are highly correlated. However, collinearity diagnostics indicated no multicollinearity with respect to partisan politics and the two measures of activation.

Empirical analysis

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the main variables of interest and shows averages of PES spending, party representation in cabinets and the strictness of conditions and sanctions. PES expenditures have seen major fluctuations during the past three decades. In terms of average expenditure, a rise in the beginning of the 1990s was accentuated after the onset of the oft-cited ‘activation turn’, and then stabilized on a higher level (OECD, 2015b). As evident from the table, there is substantial variation across countries in terms of resources devoted to PES. The scope to detail each country is limited, but some notes should be made concerning outliers. Netherlands and Denmark, eg., clearly spend more than other countries. Since the 1990s, both countries have adopted a ‘flexicurity’ approach, which is a collection of policies that aim to promote work incentives (or flexibility) combined with high levels of social security and ALMP, of which PES is a part (Boeri, Conde-Ruiz, & Galasso, Reference Boeri, Conde-Ruiz and Galasso2012; Van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2004; Van Oorschot & Abrahamson, Reference Van Oorschot and Abrahamson2003). This may, to some degree, explain the higher spending. As shown by Knotz (Reference Knotz2018), the strictness of sanctions and conditions has increased substantially in many countries since the 1980s, well before the ‘activation turn’ in the late 1990s, which is often cited as the watershed for ‘demanding’ activation (Freeman, Reference Freeman2005; Nelson, Reference Nelson2013).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Averages between 1985–2011.

Abbreviations: PES, public employment services; PPP, purchasing power parities.

Regression results

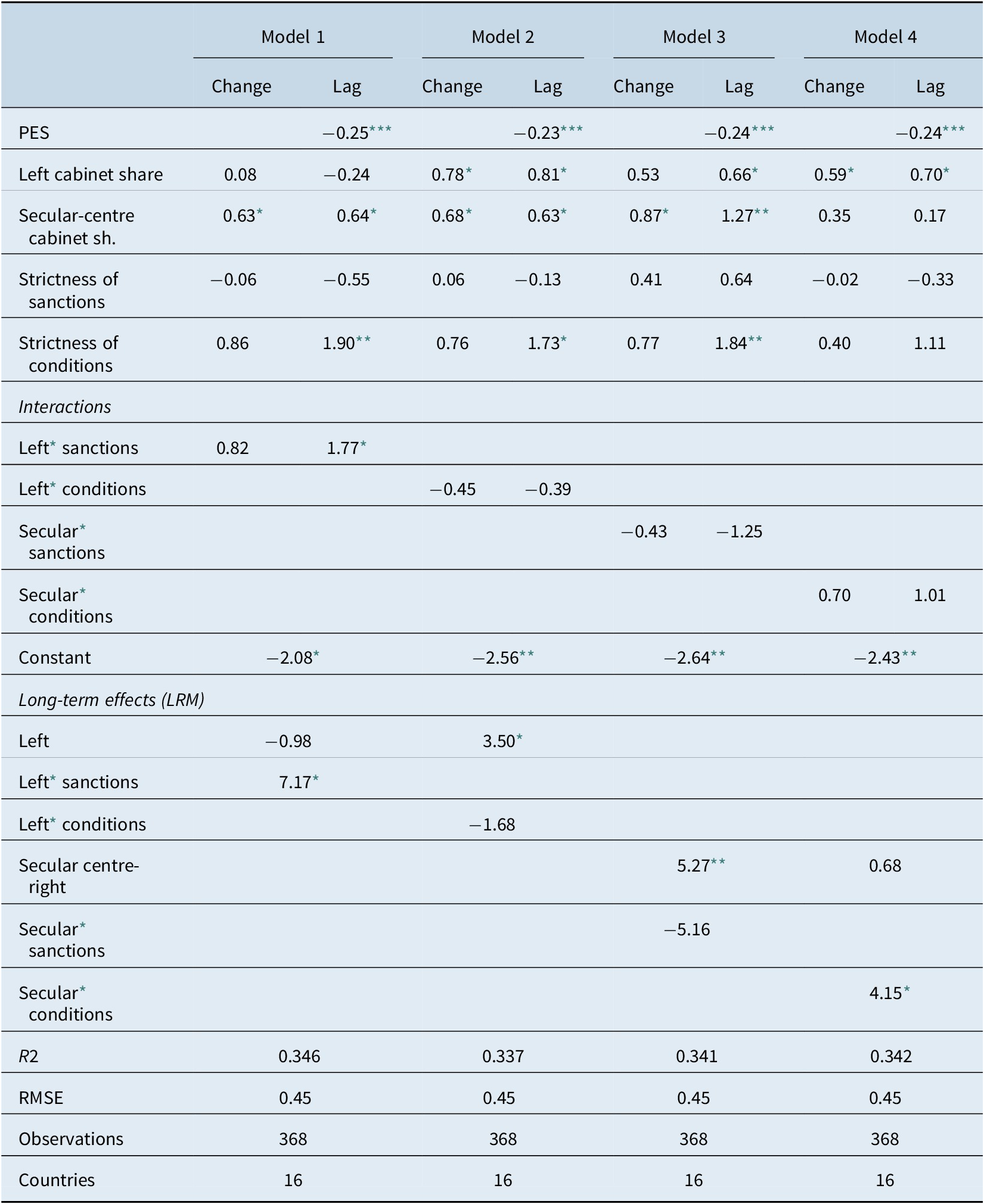

We begin by doing a multivariate ECM on the determinants of total PES spending over the entire period from 1985 to 2011. The results of the regressions are presented in Table 2. The first model includes partisan politics, and the second model adds measures of ‘demanding’ activation. The underlying assumption is that when we control for the two aspects of ‘demanding’ activation, what remains reflect the ‘enabling’ aspects of the PES. When comparing the estimates from the first two models, the need of incorporating conditionality when assessing the effects of partisan politics on PES spending seems to be confirmed. Partisan effects are revealed only when controlling for the strictness of sanctions and the strictness of conditions. When doing so, left and secular centre-right parties are associated with higher spending on PES compared to confessional parties, which are the reference category. Both differenced and lagged estimates show that when cabinet shares of left or centre-right parties increase, PES spending also increase. With respect to the strictness of sanctions and the strictness of conditions, respectively, only the lagged estimate for strictness of conditions seems to be associated with higher expenditure. These results hold when controlling for macro-economic and contextual factors in the last model. That partisan effects are revealed only when including ‘demanding’ activation indicates that the two are related even though, as discussed above, partisan politics has been shown to not be related to the increase of conditionality as such. I will return to this issue below.

Table 2. Determinants of PES expenditure 1985–2011.

All models include country fixed effects and panel-corrected standard errors with panel-specific autocorrelation.

Abbreviation: RMSE, root mean square error.

+ p < 0.1.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

Expressing the results from Table 2 in terms of temporal dynamics, there is evidence of long-term effects as several LRM are statistically significant. The LRMs show that partisanship and strictness of conditions have a long-term relationship with spending on PES, where increased cabinet shares for left and secular-centre right parties as well as increased strictness of conditions are associated with increased spending on PES over the long-term. For strictness of conditions the estimates are robust to the inclusion of macro-level controls, whereas long-term effects of partisanship are less stable, although statistically significant at the 10 per cent level.

As noted, partisan politics and ‘demanding’ activation may be correlated. One way of exploring this potential correlation is to introduce interaction terms between partisan politics and the two measures of conditionality. However, since the main effects must be evaluated together with the interaction term, it is useful to illustrate the interactions rather than interpreting coefficients directly, which is done by plotting marginal effects based on regression results (full results are available in the Appendix, Table A3). Since the relationship between partisan politics and activation is assumed to mainly be contingent on the level of activation, only the long-term marginal effects, based on variables expressed in levels, are shown.Footnote 3

Figure 1 shows marginal effects of partisanship at different values of the two measures of ‘demanding’ activation (based on the value range in the sample). The figure thus illustrates how effects of partisanship change in situations of higher or lower benefit conditionality. The results largely confirm the theoretical expectations. Left parties seem to spend less on PES as benefit conditions become stricter (statistically significant for low- to mid-level strictness of conditions). In contrast, the effects of left parties are strengthened and associated with more spending on PES as benefit sanctions become stricter (which holds for high levels of strictness). For secular-centre right parties, these effects are essentially reversed.

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of partisan politics. Note: The bold part of the lines indicates statistically significant marginal effects at the 95 per cent level.

Sensitivity analysis

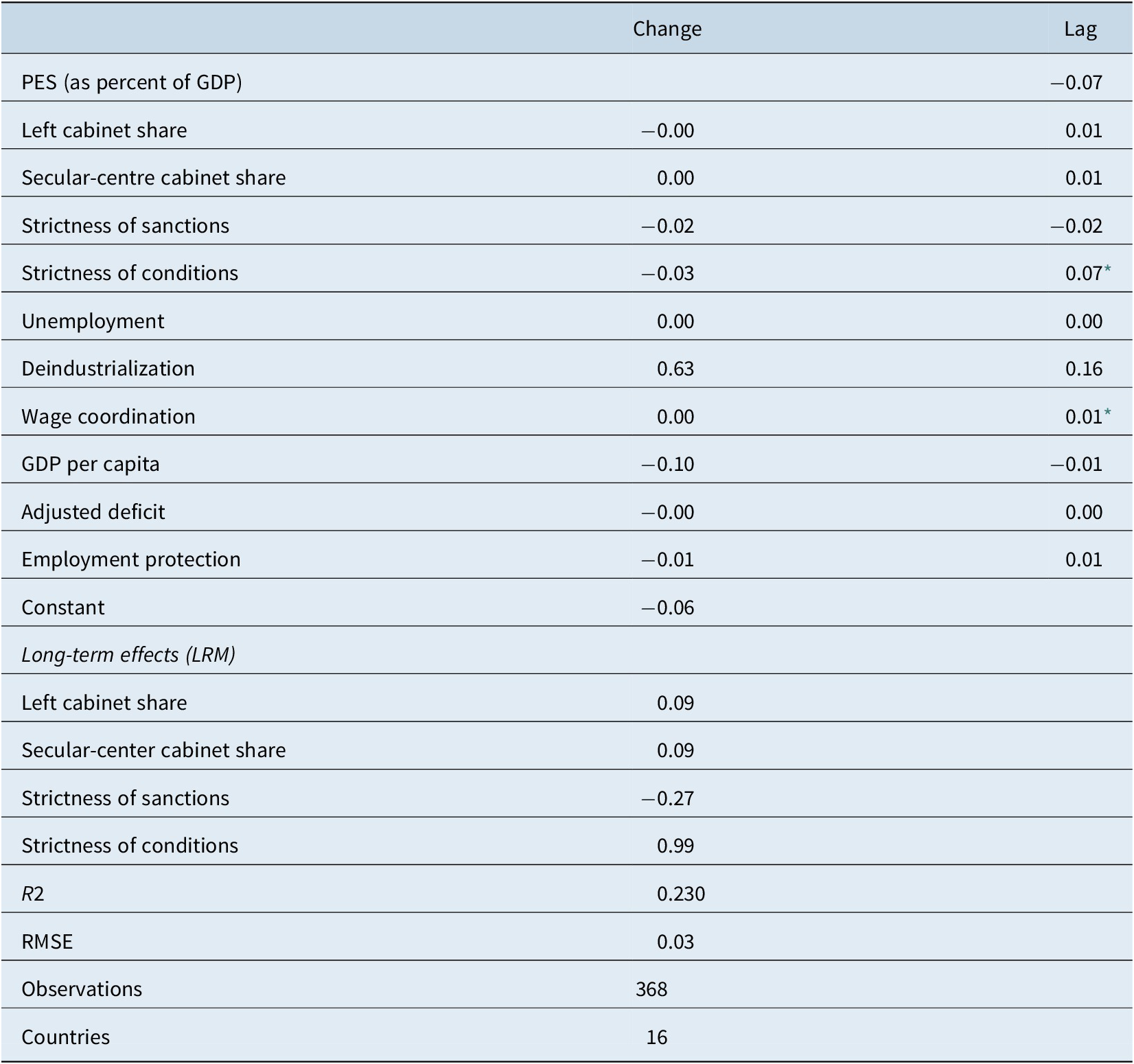

As noted above, there are various ways of measuring government spending. I have therefore estimated models where the dependent variable, PES spending, was defined as total spending on PES as a percentage of overall GDP. The results of this regression are available in Table A4 in the statistical appendix, restricted to show estimates related to partisan politics and strictness of conditions and sanctions. The signs of coefficients are mostly in the same direction as in the previous models with respect to partisan politics and benefit conditionality. However, the effects are not statistically significant at the 5 per cent level. It is likely that there is too little variation when considering PES spending as a percentage of GDP, which produces imprecise estimates. Additional sensitivity analysis included adding time fixed effects and jack-knife exclusion of countries. Including fixed effects for time and excluding one country at a time yielded similar, but less precise, estimates as shown in the main models.

Conclusions

This study set out to explore determinants of resources devoted to PES and asked whether partisan politics is related to PES once we consider the development of ‘demanding’ activation, and whether the development of activation in itself, as manifested in benefit conditionality, was related to PES spending. Beginning with the latter question, the results indicated that the strategy to use monitoring and sanctions to curb expenditures is not unequivocally successful. Increasing strictness of conditions, ie., restrictive access to benefits, was associated with increased total spending on PES. With that said, the costs related to monitoring must also be weighed against the reduced costs that increased conditionality could produce in relation to, eg., unemployment insurance. With respect to the role of political parties, the results indicated that partisan politics is a relevant determining factor for PES spending when controlling for changes in the strictness of two indicators of benefit conditionality. Although the increase in ‘demanding’ activation has been shown to be unrelated to partisan politics in other studies (Knotz, Reference Knotz2019), the fact that ‘demanding’ activation acts as a suppressor to partisan politics indicated that they are correlated, which was explored by examining the interplay between partisanship and benefit conditionality. While both left and secular centre-right parties were associated with increased spending on PES compared to confessional parties, the interplay with benefit conditionality had distinct patterns. Left parties were primarily associated with increased spending on PES in contexts where the strictness of benefit sanctions was high. This could be construed as a strategy to retain a generous insurance in terms of access, while still showing a willingness to emphasize the duties of the unemployed in order to avoid electoral backlash. Secular centre-right parties, on the other hand, were associated with increased spending when the access to benefits was stricter, which could reflect that support for the unemployed has traditionally not been a priority. Instead of sanctioning those already unemployed, secular centrist-right parties curb the right to benefits to create an incentive to avoid unemployment, while at the same time devoting resources to the PES to facilitate faster transitions from unemployment into work.

While this paper has argued that the role of partisan politics is relevant to consider in relation to PES, especially when we can account for the coercive elements of the PES, it should be noted that the current scholarly debate has raised criticism towards the ‘traditional’ left- versus right-wing perspective on partisan politics, instead emphasizing, eg., changing electorates and the role of context with respect to policy development (Häusermann, Picot, & Geering, Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013). However, the reduced salience of class politics in terms of ‘policy’ reform may instead be evident when considering ‘institutional’ reform, where power-resources may be shifted to produce more long-term effects on redistribution that follow the traditional left–right scale (Elmelund-Præstekær & Klitgaard, Reference Elmelund-Præstekær and Klitgaard2012; Klitgaard, Schumacher, & Soentken, Reference Klitgaard, Schumacher and Soentken2015). To some degree, the results of this study support this claim. The increase of ‘demanding’ activation seems to follow the logic of policy reform, where partisan politics is less salient, but changes in resources devoted to PES reflect institutional reform where partisan politics is still relevant to consider. However, there is still need to properly delineate political preferences towards various policies or interventions. The theoretical reasoning and results of this study suggests that it is important to not impose expectations from the ‘traditional’ partisan politics either. Whereas left parties are shown to conform to the assumption of expansive policies, PES is a type labour market policy palatable for centrist-right parties as well since PES spending can involve measures that are easily combined with a market logic and incentives. Confessional parties, on the other hand, have historically not been known to promote labour market policy that involve government intervention, thus following a different logic to that of social policy. Thus, preferences for welfare state policy is not just a reflection of left and right party preferences for expansion versus retrenchment, but can also be linked to other dimensions relevant for a particular type of policy, which needs to be addressed whenever the role of political actors is examined in welfare state development.

A. Appendix

Table A1. Average lags for independent variables.

Obtained through estimation of ADL without covariates, where lags are chosen according to lowest BIC.

Table A2. Fisher panel unit-root tests (augmented Dickey-Fuller regressions).

H0 – All panels contain unit roots. H1 – At least one panel is stationary. A p value below 0.05 entails rejection of null. Additional lags included in ADF regressions in parentheses. *Indicates inclusion of drift term. Deindustralization is detrended, as the Fisher test indicates a time trend. For other variables, including a time trend yields similar results as shown.

Abbreviation: PES, public employment services.

Table A3. Interaction models.

All models include all macro-level control variables.

Abbreviations: PES, public employment services; RMSE, root mean square error.

Table A4. Robustness check. PES spending as percent of GDP.

Includes country-fixed effects, panel-corrected standard errors and panel-specific autocorrelation.

Abbreviations: PES, public employment services; RMSE, root mean square error.