Introduction

Despite significant advancements in medicine and science, higher burdens of disease persist among Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Indigenous, and some Asian populations [Reference Golden, Brown and Cauley1,Reference O’Keefe, Meltzer and Bethea2]. Unfortunately, these populations have been historically excluded and underrepresented in clinical research, especially clinical trials [3].

Clinical Trial Enrollment Among Underrepresented Minority Groups

While Black/African American individuals represent 14.2% of the US population, they comprise only 5% of clinical trial participants [4]. The racial disparity is even greater among individuals of Hispanic or Latino heritage, representing nearly one-fifth (18.7%) of the US population yet accounting for 1% of trial enrollment [4]. This lack of participant diversity affects the generalizability of the safety and efficacy of novel therapies.

Low clinical trial enrollment among underrepresented minoritized communities (URMs) is complex and multifactorial, yet can be attributed to a wide range of well-known factors including mistrust of researchers and medical institutions, lack of awareness and education of clinical trials, financial constraints, logistical burden, and limited access to study opportunities [Reference Langford, Resnicow and An5–Reference Smith, Wilkinson, Carney, Grove, Qutab and Getz9]. In spite of these barriers, research indicates that when provided with adequate information and the opportunity to participate, URMs express the same willingness to participate in clinical trials as their White counterparts [Reference Wendler, Kington and Madans10].

Recent calls to action and guidance for the inclusion and prioritization of URMs in clinical trials have been issued [11]; however, more work is needed to identify methods that improve diversity in clinical trials.

This paper will describe best practices in multicultural and multilingual awareness-raising strategies used by the Recruitment Innovation Center [Reference Wilkins, Edwards and Stroud12] to increase minority enrollment in clinical trials. These methods include culturally tailored messaging, community outreach, and accounting for health literacy. The Passive Immunity Trial for Our Nation will be used as an example to highlight real-world application of these methods to raise awareness, engage community partners, and recruit diverse study participants.

Methods

Best Practices for Multicultural and Multilingual Awareness-Raising and Outreach

It is critical for research teams to have an in-depth understanding of language, acculturation, and race to address common barriers to the recruitment and retention of URMs. Research teams should consider using a comprehensive strategy to raise awareness that focuses on: 1) culturally tailored messaging, health literacy, and language, 2) diverse communication channels, and 3) outreach and collaborations with community organizations to increase awareness and build community trust in research. These methods were utilized in the PassITON trial but they are not an exhaustive list of multicultural and multilingual awareness-raising and outreach strategies.

Culturally Tailored Content

Cultural tailoring

Traditional clinical trial messaging often lacks cultural sensitivity and racial nuance which can impede a participant’s understanding of the research and perceived relevance to their community [Reference Brown, Lee, Schoffman, King, Crawley and Kiernan13]. Cultural tailored content can include using community-specific statistics and racially concordant images and leveraging community values and belief systems to shape message [Reference Takeshita, Wang and Loren14]. This strategy encourages the uptake of information and has been shown to improve health behavior activities [Reference Shen, Peterson and Costas-Muñiz15]. Engaging culturally competent experts and organizations may also help support the development and accuracy of culturally tailored messages. Organizations with extensive expertise in working with diverse populations and wide-reaching relationships with URM-focused organizations should be considered for partnership.

Literacy

Health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals can find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” [Reference Chang and Kelly16]. Using easy to understand, plain language on study materials and resources can help to overcome education and comprehension challenges within a clinical trial [Reference Chaudhry, Herrin and Phillips17].

Language

Clinical trials should strive to meet the diverse linguistic needs of URMs. Comprehensive translations of recruitment materials and consent forms should be done to ensure that all interested participants have enough information to make informed decisions about trial enrollment. Socio-cultural nuances should also be considered when translating materials. A process of “transcreation,” a style of translation that preserves the original message, tone, and emotion of the original text, may be helpful [Reference Díaz-Millón and Olvera-Lobo18]. This can be achieved primarily through utilizing tailored images and culturally congruent text.

Communication channels and avenues

Utilizing multiple communication channels can assist with reaching racially marginalized populations. Low-cost, wide-reaching communication channels like social media have a wide adoption and have the potential to reach a range of audiences [Reference Thompson19], including URMs and could be used to foster trust with the research enterprise. Other traditional communication channels such as broadcast media [Reference Kelley, Su and Britigan20] and using healthcare professionals [Reference Kelley, Su and Britigan20] may resonate more with certain demographics. Accounting for the diverse preferences in communication channels is important to engaging URMs in clinical research.

Community Outreach

The often-strained relationship between the scientific community and URMs due to mistrust is well documented and requires the engagement of community champions and partners to inform, support, and disseminate information about clinical trials [Reference De las Nueces, Hacker, DiGirolamo and Hicks21]. Community outreach, in contrast to community engagement which emphasizes mutually beneficial relationships and bi-directional communication amongst stakeholders [Reference McNeill, Wu, Cho, Lu, Escoto and Harris22], focuses on strategic coordination amongst stakeholders and one-directional communication to priority populations [Reference McNeill, Wu, Cho, Lu, Escoto and Harris22]. Community outreach can be a pathway for building trust and encouraging trial participation. This can be achieved through engaging community influencers, trusted leaders, religious institutions, and community organizations [Reference Wilkins23]. Engaging community members through studios [Reference Joosten, Israel and Williams24], focus groups, town halls, and community conversations are just a few ways in which research teams can leverage community perspectives and expertise to help increase clinical trial awareness and enrollment [25].

The PassITON Trial

The Passive Immunity Trial for Our Nation (PassITON) was a multicenter randomized controlled trial studying the efficacy and safety of convalescent plasma as a treatment for adults hospitalized with COVID-19 [Reference Self, Wheeler and Stewart26]. Patients were enrolled across 26 hospitals between April 2020 and June 1, 2021. The trial began at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and then expanded to 25 additional sites in September 2020 with funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

PIO I: The plasma collection arm of the trial (PIO I) took place at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and was collected from adults residing in and around Nashville, Tennessee who had recently recovered from COVID-19 [Reference Self, Wheeler and Stewart26].

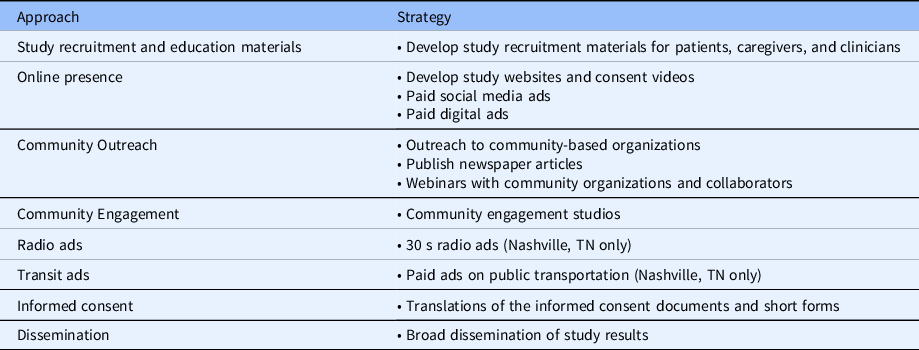

Beginning in August 2020, the PassITON trial and the Recruitment Innovation Center developed a comprehensive plan to prioritize racial and ethnic diversity, equity, and inclusion in the trial. As part of this, we contracted with the marketing organization Culture Shift Team, a consulting organization of experts in multicultural awareness raising, public relations, and community engagement, to create a strategy to raise national awareness about the trial. Our efforts focused on developing multicultural and multilingual study recruitment materials, creating an online presence, and broad community outreach and engagement (Table 1).

Table 1. Comprehensive outreach campaign

This distinctive approach to clinical trial awareness raising utilized an innovative and comprehensive strategy that targeted components within the research recruitment continuum [Reference Wilkins, Edwards and Stroud12] and focused on tailoring materials and community outreach.

Study recruitment materials

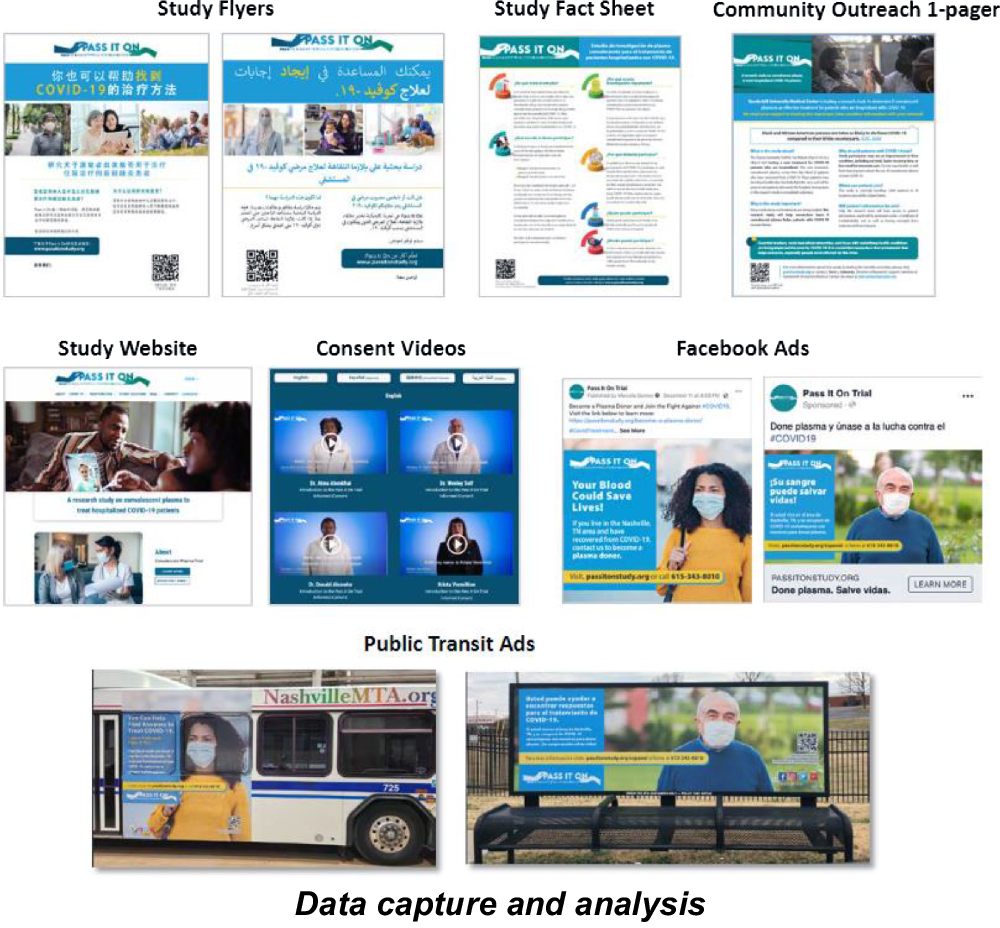

A suite of tailored, multicultural recruitment materials was created for the trial, including print and digital resources aimed at patients and their families, as well as clinicians. These included flyers, posters, study fact sheets, study websites, informed consent videos, participant testimonial videos, a clinician one-pager, and Clinician Study Application (CSA) (Fig. 1). All patient-facing materials were available in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Arabic based on commonly spoken languages across the USA and participating trial sites. Study videos were available in all four languages and featured diverse speakers from various backgrounds and cultures.

Fig. 1. Examples of recruitment materials used to raise awareness about PIO.

Online presence

The trial developed a robust online presence through the creation of a study website, social media profiles and ads, and digital ad placement. The study website (www.passitonstudy.org) was designed to provide the public and potential study participants with an overview of the trial, information about COVID-19, and at-risk groups, and was available in four languages – English, Spanish, Chinese, and Arabic.

Social media profiles were created on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and were used to push out organic posts as well as paid social media advertisements to raise national awareness about the trial, especially among URM communities. Filtering was used for Facebook ad placement to determine key market areas and select target audiences, including:

-

Location: Zip codes within 50-mile radius of participating sites with a Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Middle Eastern/North African, or Chinese population of 10% or higher and with 10,000+ active COVID cases

-

Age: 18 years and older

-

Gender: All

-

Language Preference: English, Spanish, Chinese, and Arabic

Digital ads were used as banner advertisements on 30 select English and Spanish websites with diverse viewership including the NAACP and El Nueva Dia to promote the study and direct viewers to the PassITON study website.

Community outreach and engagement

Early in the trial, three community engagement studios [Reference Joosten, Israel and Williams24] were held with Black, Latinx, and rural community stakeholders to help shape messaging of trial recruitment materials and strategize an inclusive approach to outreach and engagement. These community stakeholders identified trusted organizations to engage with, communication platforms for trial awareness raising, and methods to establish trust and rapport with URMs. The translations, tailoring, and cultural congruency for Chinese and Middle Eastern and Northern African communities were informed by the multicultural marketing organization.

National outreach to nonprofit and advocacy organizations included emailing culturally tailored information about the trial and requesting their support and assistance in disseminating information through their identified channels. Meetings and webinars were conducted with interested organizations and with members from the research team as an opportunity for communities to learn more about the trial. Articles were also written and published in various newspaper outlets in select markets (e.g. Baltimore, MD and Nashville, TN), with URM readership.

Broad dissemination of overall study findings was prioritized and planned for from the onset of the trial. Community collaborators will receive a plain-language written summary and video of the trial’s results to share with their stakeholders.

Radio and public transportation advertisements

Thirty-second radio ads were placed on three local radio stations in middle Tennessee (Nashville, TN), to encourage plasma donations among those that had recovered from COVID (PassITON plasma collection), and also raise awareness about clinical trial participation (PassITON clinical trial). Radio ads were placed on stations with diverse listenership. Radio ads ran from January 2021 through March 2021 and were in English and Spanish.

An informational campaign encouraging plasma donation from those that have recovered from COVID-19 in the Nashville, TN area ran from January 2021 to April 2021. Advertisements in English and Spanish were placed on public buses, bus shelters, and benches on select routes and neighborhoods in Nashville, TN. Ads contained the study website URL and QR code for scanning and learning more about the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent documents were translated into over 20 languages, including Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and Hindi. Certified professional translators were used to translate the materials and were monitored for accuracy using the contracted multicultural marketing agency.

Data Capture and Analysis

Several data points were used to assess diversity, awareness, interest, and engagement in the trial (Appendix A). Baseline demographic data of trial participants were summarized to show diversity and representativeness in the trial. For materials usage, weekly QR code scans and CSA opens were monitored. For website traffic, descriptive data from Google analytics were summarized. For social media, data across Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter platforms were monitored on a weekly basis to determine engagement, including total views, likes, and clicks.

Results

Enrollment Diversity

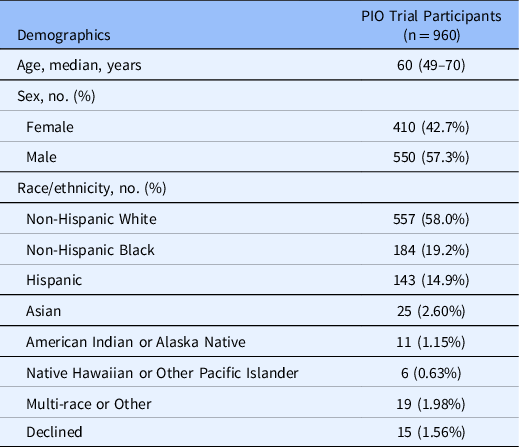

A total of 974 participants enrolled and were randomized into the trial. After randomization, 14 participants withdrew consent, resulting in a primary analytic population of 960 patients. The median age was 60 (range: 49–70 years), 410 (42.7%) were female, 184 (19.2%) identified as Black or African American, and 143 (14.9%) were of Hispanic/Latinx heritage. Table 2 details the baseline enrollment characteristics of trial participants.

Table 2. Baseline enrollment demographics across PIO trial

Awareness Raising

Website and social media

From November 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021, the PassITON study website received 33,325 views among 18,104 users. A detailed breakdown of website metrics by site language can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Study website traffic (November 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021)

* Source: Google analytics; Views were the number of times a page was viewed by a user; Users were number of unique individuals that visit the website.

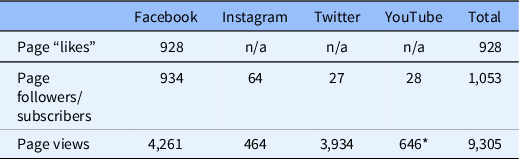

A total of 158 posts were placed on Facebook from December 2, 2020, to May 18, 2021. These posts reached 2,142,028 users, resulting in engagement from 2.8% of those reached (n = 60,402). Forty-one short videos were posted on Facebook and were viewed 146,867 times. The PIO profile gained 928 likes, 934 followers, and resulted in 4,261 page views. Additional metrics for Instagram and Twitter engagement are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4. Social media engagement (December 2, 2020–May 18, 2021)

* Video views.

Public transportation advertisements

Public transit messages ran from December 2020 to March 2021 throughout Nashville, TN. Fifty-four messages were placed on buses, shelters, and benches, in both English and Spanish. QR code data indicated 41 scans from the English and Spanish messages.

Community Outreach and Engagement

Outreach

The PIO trial reached out to organizations across the USA, including community-based organizations, historically Black Colleges and Universities, religious organizations, and Greek fraternities and sororities. We participated in five webinars and collaborated with 75 organizations to share information about the trial across their networks and channels (e.g. Facebook, email listservs).

Engagement

The three community engagement studios informed study messaging and recruitment materials. This feedback included: 1) Distributing study information to COVID testing sites, local clinics, and other community-based sites, 2) Developing videos that explain the study and highlight risks and inclusions of people with chronic health conditions, 3) Implementing a multi-pronged approach to communication that includes traditional methods and social media

Discussion

With over 40% participation among URMs, the PassITON trial was successful at enrolling a diverse patient population, in comparison to trial site demographics, national COVID-19 surveillance data [27], and other clinical trials. Trial demographics suggest that using a multicultural and multilingual awareness-raising strategy may have substantive impacts on reaching URMs in comparison to previous studies that demonstrated 23% and 34% participation of URMs, respectively [Reference Sullivan, Gebo and Shoham28,Reference Korley, Durkalski-Mauldin and Yeatts29].

Linguistic translation of recruitment materials and informed consent documents offered the public and potential participants information about the trial that was accessible and culturally tailored. Over a quarter of study website views were on non-English webpages, indicating interest and engagement among people whose primary languages were Spanish, Chinese, or Arabic. Clinical trial teams should consider translating their study materials, coupled with in-person translation services, to recruit and enroll a diverse patient population.

Similar to previous studies, social media also proved to be a viable strategy for raising national awareness about the trial and engaging with the public [Reference Thompson19]. Social media platforms, such as Facebook, offer research teams the ability to target and reach specific populations using filtering criteria, tailored messaging and images, and testing to see what posts and paid advertisements resonated most with the intended audiences. Regular postings and paid messages garnered more than 2 million views on Facebook alone.

The use of other awareness-raising strategies such as radio messages and public transit messages also provided opportunities to raise local awareness about clinical trials and could be leveraged as part of a larger informational campaign strategy [Reference Voorveld30,Reference Faroqi, Mesbah and Kim31]. This unique approach allowed us to reach essential workers and other commuters who rely on public transportation. While we were able to assess engagement with these messages through QR codes, this falls short of their true reach and impact, as it is difficult to evaluate the impact of these messages on the audience they reached. Additionally, while these strategies may be effective, they may not be viable options for more study teams due to the large costs associated with these efforts.

In line with previous research, community outreach was a valuable way to build rapport and establish community relationships [Reference Wilkins23], even in an in-patient trial such as PassITON. Our expansive yet tailored outreach strategy signaled to our study participants, regardless of their participation site, that we had a vested interest in their communities’ stakeholders, and that these organizations supported the work of the PassITON trial. With national outreach to community organizations, information about the trial was shared broadly among a wide range of audiences.

Working with a multicultural awareness-raising organization may be a worthwhile strategy to explore as part of a larger strategy to raise awareness about a trial. Research teams may benefit from engaging a multicultural marketing and public relations organization to complement and support their trial’s recruitment and retention efforts. While many marketing organizations may lack direct expertise in clinical trial recruitment and retention, their expertise with tailored messaging, increased considerations for health literacy and language, access to diverse communication channels, and expansive access to community organizations could help to enhance industry standards for clinical trials, overcome barriers related to mistrust among URMs, and develop unique approaches to clinical trial recruitment and retention across the life of a trial.

Lessons Learned

Leveraging a multicultural marketing organization was an effective strategy for the PassITON trial. Several lessons were learned throughout this study that may be beneficial to other study teams. First, many organizations have limited experience and expertise in clinical trials. Research teams should ensure that the organization understands the relevant regulatory process involved in developing recruitment materials and community outreach. This may also help to streamline IRB submissions and improve timelines. Second, teams should be proactive in communicating their preferred data collection and report-out methods. For example, weekly reporting of website analytics. Third, regular meetings and check-ins were essential to maintain ambitious timelines of deliverables and to monitor the progress of outreach efforts.

Limitations

We acknowledge a few limitations in our methods and results. First, given that the goals of our informational campaign were to raise national awareness about the trial, many of our metrics (such as views, clicks, and QR code scans) are only “proxies.” Therefore, a direct causal relationship between our outreach strategies cannot be determined. Future research could explore the direct link between large-scale awareness-raising activities and clinical trial recruitment and enrollment. Second, we were unable to translate materials into Native American/American Indian tribal languages or conduct outreach with tribal communities due to tribal-specific regulations. Future consideration and early planning should be done to ensure that tribal populations are included in outreach efforts. Third, the immensity of our translations caused significant IRB delays and impacted the dissemination of materials. Future studies should plan early for delays. Fourth, engaging an outside marketing organization is costly and financially inaccessible for many clinical trials. The total cost for engaging this organization was approximately $330,000. A detailed breakdown of costs is outlined in Appendix B.

However, this paper details best practices and successes that teams may be able to replicate on their own at lower costs. We suggest study teams budget for additional recruitment expenses for diversifying study participation and enrollment. Fifth, because of time limitations we were unable to conduct community engagement studios with the Chinese and Middle Eastern/Northern African communities. Future studies should allow for adequate time for feedback from priority populations. Lastly, since the PassITON trial was based in the USA, our methods may not be generalizable and applicable to URMs outside of the USA.

Conclusion

The PassITON trial offers a real-world example of multicultural and multilingual awareness-raising strategies to enhance and support racial and ethnic diversity in a clinical trial. Considering the current existing racial and ethnic homogeneity in clinical trials, these proposed strategies may assist study teams with overcoming challenges to the recruitment and retention of URMs and enhance racial diversity in their trials.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.506.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Culture Shift Team (Nashville, TN) for their expertise in multicultural marketing and outreach and their efforts to raise national awareness about this trial. We extend our sincere thanks to the many community organizations who collaborated with us and shared information about participating. We would also like to thank the Community Engagement Studio team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center for their support in engaging community members to inform the trial. Lasty, we are grateful to the participants who took part in this study, the care teams who took care of them during their hospitalization, and the research site teams that took part in this trial.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.