At the manor court of Little Downham, Cambridgeshire, in a session held 27 September 1392, the lord's reeve, Robert Rote, presented eight “stray” animals. He declared that “one mare, one brown mare with a foal, one grey mare with a foal, one grey female foal, and two black steers” had appeared inside the lordship around the feast day of the Decollation of Saint John the Baptist (29 August) about a month earlier. The court roll described these animals as de ext[ra]y and declared that no one had yet come to claim them. The court therefore ordered that the discovery of these stray beasts was to be advertised (“proclaimed,” in the legal jargon) around the local community.Footnote 1 The story was continued in the following court two months later. On 5 December, William Lutgate of Doddington came with “six hands” (that is, six men to support his claim) to prove ownership of one of the horses, a “whitblakspottyd” mare. William paid a fee of 12d. to the lord, and the mare was released to him.Footnote 2 However, the remaining seven animals remained unclaimed, and an official was ordered to proclaim them once more. This happened again in courts of February and July 1393.Footnote 3 It was not until a court of 1 September 1393 that the story ends. The animals having remained unclaimed inside the lordship of Little Downham for a year and a day, the court stated that they would become the lord's property as forfeited chattels.Footnote 4

Events like these were not occasional curiosities; the narrative outlined above is simply one example of a process that played out thousands of times in manor courts across late medieval England. Even a superficial examination of manorial documents reveals that stray animals were an ever-present nuisance of everyday life for rural communities. The frequency of references in court rolls illustrates just how much time manorial courts spent administering the stray system,Footnote 5 and the sheer number of bylaws dealing explicitly with the management of loose livestockFootnote 6 reveals the deep concern that medieval communities shared about animals damaging their crops. From the lord's perspective, strays were not only a threat to open-field crops sown by them and their tenants but were also a significant potential source of livestock for their own demesnes (lords’ personal farms, as opposed to the lands of their tenants).Footnote 7 However, despite the centrality of stray animals to medieval rural life, the nature of the system that administered them remains poorly understood.Footnote 8

In this article, we have two aims. Through the analysis of a substantial sample of manorial court rolls, spanning the years 1274 to 1453 and containing a total of 1,781 court sessions, we illustrate and explicate the stray system. We describe the legal framework that undergirded the system and explore its many levels of operation, from the royal franchises that granted the rights to claim strays to the courts that applied and mediated these rights on the manor, and finally to the individuals who worked in the system and made the system work. Secondly, we use the stray system to contribute to recent discussions of the role of manorial structures in village communities and what they reveal about lord-tenant relationships.

Specifically, we argue that the stray system is a clear example of a public good. Although strays could be forfeit to the lord, and so appear to have been a seigniorial perk, our assessment of the operation and the economics of the stray system in practice reveals that lords and tenants collaborated to provide this service for their community. Why was such a public good necessary on medieval manors? Stray animals represented a significant risk to the arable land held by both lords and tenants, and managing strays was thus of vital importance for the whole community. In a world where most of the population was reliant on agriculture—already vulnerable to the vagaries of the environmentFootnote 9—to provide a basic livelihood, any potential damage to a crop would have been a very real concern. While in the modern period interventions such as barbed wire protected private agricultural land and mitigated this problem, limited medieval technology and the communal nature of agriculture required a different solution.Footnote 10 However, in managing the threat of wandering livestock, the property rights of owners had to be clearly protected to avoid violent disputes stemming from accusations of theft and conflict over ownership. The manorial court's management of strays provided an institution to resolve these countervailing pressures. Ultimately, it provided an imperfect but workable system that added an element of protection to crops in the fields while offering a tangible form of redress for the accidental loss of livestock.

Historiography: Lord–Tenant Dynamics and the Role of Manorial Structures in Medieval England

The relationship between lords and tenants has been a long-standing subject in the historiography of the late Middle Ages. A particularly influential interpretation, chiefly developed in the postwar period, is a Marxist explanation of late medieval economic and social development arguing that the relationship between lord and tenants was the primary determinant of economic well-being.Footnote 11 This model proposes that the feudal mode of production fundamentally involved a process of “surplus extraction,” in which lords secured their incomes through expropriating the product created by their tenants.Footnote 12 The form of this extraction, which varied between places and over time, consisted of some combination of rents and jurisdictional privileges.Footnote 13 In this schema, the relations between lords and tenants were inexorably conflictual.Footnote 14 At least some of these jurisdictional privileges could, it is argued, be levied at the lord's will and thus had “an arbitrary and unexpected character.”Footnote 15 Often, the lord's manor court has been seen as a crucial instrument for the extraction of these rents and privileges. The court gathered information about who owed seigniorial dues and punished those who failed to render them, and therefore acted as a key tool of oppression.Footnote 16

However, more recent contributions, written from both Marxist and revisionist perspectives, have tended to complicate this view of manorial institutions. A crucial focus has been on the role of custom as a constraint on lordship. These were local norms and practices that had developed over centuries and defined the rights of lords more specifically than theoretical legal entitlements.Footnote 17 For example, Mark Bailey has demonstrated that tallage, typically the right of lords to charge an extraordinary tax on their tenants, was not a “monetary facet of lordly power” that could be levied at will, as R. H. Hilton had claimed,Footnote 18 but was in reality “neither arbitrary nor unpredictable” and “heavily influenced by custom.”Footnote 19 Local customs were a powerful force that acted to routinize and fix both the land rents and feudal dues that tenants could expect to pay to their lords.Footnote 20 Significantly, manorial custumals and courts provided key channels through which tenants could define and shape custom and therefore were a crucial part of this process.Footnote 21

Other studies have challenged the notion of a strictly extractive lord-tenant dynamic by examining the ways in which manorial structures could work positively to serve the purposes of seignorial tenants.Footnote 22 This new direction has been partly the result of a shift away from analyzing peasants in terms of their relationship with lords to examining them as economic actors engaged in a far wider network of market-based associations.Footnote 23 Although historians such as Hilton working in a Marxist framework, were always aware that peasants engaged in economic activities beyond paying rents to their lords,Footnote 24 newer studies from a “commercialization” perspective have tended to emphasize peasant economic activity as a crucial driver of economic development in the late Middle Ages.Footnote 25 In making this case, these studies argue that many manorial structures and institutions actually helped peasants by creating a constructive environment for production, investment, and trade.Footnote 26

John Langdon's exhaustive study of medieval English milling articulates such a revisionist interpretation.Footnote 27 Rather than viewing millsuit, the obligation of all tenants (as opposed to only unfree, or customary, tenants) to use the lord's mill, as a form of seigniorial extraction, Langdon demonstrated that millsuit violations were rarely recorded in court records. He suggested that this feudal practice was not enforced very actively, concluding, “Customers generally came to mills because they wanted to, not because they were forced there.”Footnote 28 He goes so far as to suggest that lords may have had a “paternalistic attitude to their tenants,” and tenants may have actually appreciated the easy access to a local mill that many lords provided.Footnote 29

Langdon's exploration of the milling industry goes some way toward rehabilitating the image of the manor court. Courts provided a direct channel from tenants to lords through which the former could raise concerns to the latter about the unfair dealing of millers or even the need for the improvement or refurbishment of community mills.Footnote 30 Such a view can be fit into a wider literature that has demonstrated the facilitative role that courts could have in medieval English village communities.Footnote 31 In this paradigm, courts could work on both individual and collective levels. In terms of individual tenants, the manor court had a significant role, most pronounced in East Anglia, in transferring customary land (the land of unfree, or villein, tenants as opposed to free tenants).Footnote 32 Property transfers not only facilitated land sales in an active market, but also allowed tenants to fashion complex inheritance strategies.Footnote 33 For both free and unfree tenants, manor courts also provided a forum for cheap and easily accessed interpersonal litigation.Footnote 34 Ultimately, manorial courts allowed tenants to enter into enforceable contracts that, in turn, fostered the growth of an array of economic activities such as a burgeoning peasant credit market.Footnote 35 Tenants also used manorial courts for a wider array of collective processes, such as registering and enforcing bylaws. These were sets of regulations drawn up by village communities concerning common lands, grazing rights, and other collective concerns. The manor court was the primary venue that dealt with these issues in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote 36 Thus, historiography has shifted in recent years to seeing the manor court as a vital institution that provided tenants with an array of commercial opportunities while also ensuring collective protections of common resources.Footnote 37

Lords did generate revenues from all of the “services” discussed above. They took fees for land transfers, charged for hearing interpersonal suits, and were paid for use of their mills. However, there is growing recognition that manorial institutions, particularly courts, also played a positive role in village communities. They did so not only by providing ways for tenants to constrain lords using the power of custom but also by facilitating a range of processes essential to the day-to-day economic and social lives of rural inhabitants. In this latter role, courts helped to create a commonality between lords and tenants, who collaborated to achieve the common objective of providing an institutional environment conducive to agricultural production and commerce.

The Legal Framework of the Stray System

The stray system offers a case that powerfully illustrates how lords and tenants could use manorial institutions cooperatively to facilitate economy activity. While every manorial lord had the right to hold a manor court, not every lord had the right to claim stray animals. This particular entitlement was part of a larger set of privileges, called franchises, that typically belonged to the crown but could be granted to lords or claimed by them through immemorial usage.Footnote 38 The famous legal treatise Bracton places the franchise of strays alongside those of wrecks and great fish as res nullius: things that “belong to the lord king because of his privilege or to those whom the king has granted such liberty.”Footnote 39

Other franchises included relatively common grants such as the view of frankpledge and the assize of bread and ales. The former allowed lords to administer the tithing system, a law and order mechanism that made ten men responsible for their fellows’ behavior,Footnote 40 while the latter empowered lords to monitor and regulate the sale of bread and ale. However, some franchises were more unusual. The right to take strays was an exalted privilege, alongside return of writs (allowing the lord to perform duties usually undertaken by royal officials), infangthief (allowing the lord to hang thieves caught red-handed within the manor), outfangthief (allowing the lord to hang inhabitants of the manor even if they committed crimes abroad), felony forfeiture (allowing lords to take both stolen goods and the chattels of convicted felons), and wreck (allowing lords to profit from items washed up from the sea).Footnote 41 These more privileged franchises often came as a package.Footnote 42

How was the franchise of stray exercised? Setting a trend that later writers would follow, Bracton wrote simply that stray livestock must be animals “which no one pursues, claims or avows.”Footnote 43 Another legal treatise, Britton, provides more detail. It places strays within the category of “those things lost and found above ground.” More importantly, the treatise defines a specific window of time for reclaiming lost livestock, stating that “if the owner demand them within the year and day, and can prove them to be his property, they shall be delivered to him.”Footnote 44 Alternatively, “waifs or estrays, not challenged within the year and day, shall belong to the lord of the franchise.”Footnote 45 The text goes on to emphasize that forfeiture to the lord was only legitimate if the animal had been clearly proclaimed throughout the 366-day period, outlining that “if the lord did not cause the beast so found to be publicly cried in manner aforesaid, then no time shall be run against the owner of the thing or beast, to bar him from replevying it whenever he pleases.”Footnote 46 So, according to Britton, for lords to claim a stray legally, they had to keep stray beasts for 366 days and also to ensure that word of the animal's discovery was appropriately advertised for this period. Only then, if the animal remained unclaimed, would it become the legal property of the claiming lord.

Importantly, lords could only exercise the franchise of stray (as with all other such franchises) within the boundaries of their own manor.Footnote 47 This restriction is exemplified in 1394 at Little Downham in Cambridgeshire, when the manor's jury specifically defined the territory in which the lord had the right to collect strays in the surrounding fenland.Footnote 48 The defining of such stray “catchment areas” could, and often did, lead to conflict between lords. The Year Books note several conflicts over who could exercise the franchise of strays on a particular manor.Footnote 49 These disputes illustrate that not only did lords seek to protect their rights to strays but also that the crown regulated lords’ claims to these privileges.

To exercise the franchise of strays illegitimately could incur heavy penalties, as a trespass case from 1382 at the court of common pleas, replete with lords and their officials, illustrates. The case hinged on who had the right to take strays within the vill of Shawell, Leicestershire. A stray mare was seized by William de Garton, the bailiff of the Prior of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in England. However, Sir John de Crophill brought suit claiming that he had the right to strays in Shawell and that his official had (lawfully) seized the mare before William had subsequently taken it.Footnote 50 William responded by arguing that, in his capacity as bailiff, he had lawfully seized the mare on behalf of his lord, who held the right to strays. Ultimately, the court decided that John's bailiff had seized the mare lawfully within his lordship.Footnote 51 William was ordered to pay damages of one hundred shillings for illegally attempting to exercise the franchise of strays where he was not entitled to do so. Similar disputes are mentioned occasionally in manorial court rolls, when officials of one manor accused neighboring manors of illicitly seizing strays.Footnote 52 For instance, in 1307 at the manor of Wakefield in Yorkshire, the court ordered that Sir Thomas de Burgh, a subtenant of the earl holding the nearby manor of Waleton, be distrained for retaining two stray horses “because no one has waif in the Earl's liberty, save the Earl himself.”Footnote 53

Disputes often hinged on identifying where an animal had first been taken as a stray. This point was an issue in asserting property rights over possessions that could wander between manors. Some court rolls even record complaints about potential strays lost to rival local lords. For instance, in 1393, jurors at Tottenham Pembrokes in Middlesex presented that an exceptionally valuable grey horse had appeared on the manor in May but that it had then escaped into an adjacent manor held by Adam Franceys, where it was arrested by Adam's bailiff.Footnote 54 From the other perspective, at Bradford (Yorks.) around 3 May 1360, the bailiff arrested a stray horse and placed it in the manor's common pasture. Subsequently, around 25 December 1360, this same horse was taken by the bailiff of the neighboring manor of Morley. The bailiff of Morley came to Bradford's manor court and argued that he was justified in taking the animal because it had first wandered in a place called “Rensthaghe outside Bradfordale” before 3 May and he had arrested the stray “in the park of . . . Morley.”Footnote 55

The legal history of the franchise of strays remains a topic that could be fruitfully subjected to further analysis.Footnote 56 However, for the purposes of this article, three relevant and important conclusions arise from this brief investigation. Firstly, the right to take strays was often held by the most powerful lords, often in combination with a portfolio of other rights. If any lords could have squeezed a surplus from their tenants, it would surely have been the ones with these extensive legal rights. Secondly, lords were active in defending their rights to strays. They utilized both their manor courts and royal jurisdictions to exercise their franchises and to resolve disputes in which strays had crossed manorial boundaries. Thirdly, legal theorists had clear guidelines on how the franchise of strays should be exercised. Of course, legal theory does not necessarily reflect legal practice. In the next section, we address this issue by close examination of the way that strays were processed through manorial courts.

The Operation of the Stray System: Lords, Tenants and Claimants

Our analysis, below, of the stray system at the manorial level, is based on 1,066 observations of strays systematically drawn from surviving court rolls of nine manors across medieval England.Footnote 57 Little Downham in Cambridgeshire, Wakefield in West Yorkshire, and Worfield in Shropshire were chosen because their court rolls survive in large numbers over long periods of time. Located in the North, the Midlands, and East Anglia, and with both ecclesiastical (Downham) and aristocratic (Wakefield and Worfield) lords, these manors give the study breadth in terms of both geography and lordship. These manors have been supplemented by shorter series of rolls from other manors from the Thames Basin region, which include manors held by the crown and religious houses.

The sample has some limitations. Most of the court rolls are drawn from either the pre– or post–Black Death period, with only one short series for Bradford crossing this divide. The composition of our sample presents some difficulty in measuring change over time in terms of the frequency or types of stray animals reported in courts. The growth of the pastoral sector and the proliferation of demesne leasing after the Black DeathFootnote 58 may have led manor courts to take a greater interest in stray animals. However, our sample cannot provide direct insights on such trends. Similarly, all except one of the manors were characterized by common field systems or common field systems with limited enclosure, and it seems logical to suggest that straying may have been a less pressing issue in communities with higher levels of enclosure. These issues await further investigation. Despite the heterogeneity of our sample and the almost two centuries surveyed, the stray system we outline seems to have been remarkably uniform, suggesting our conclusions are meaningful on a national scale.

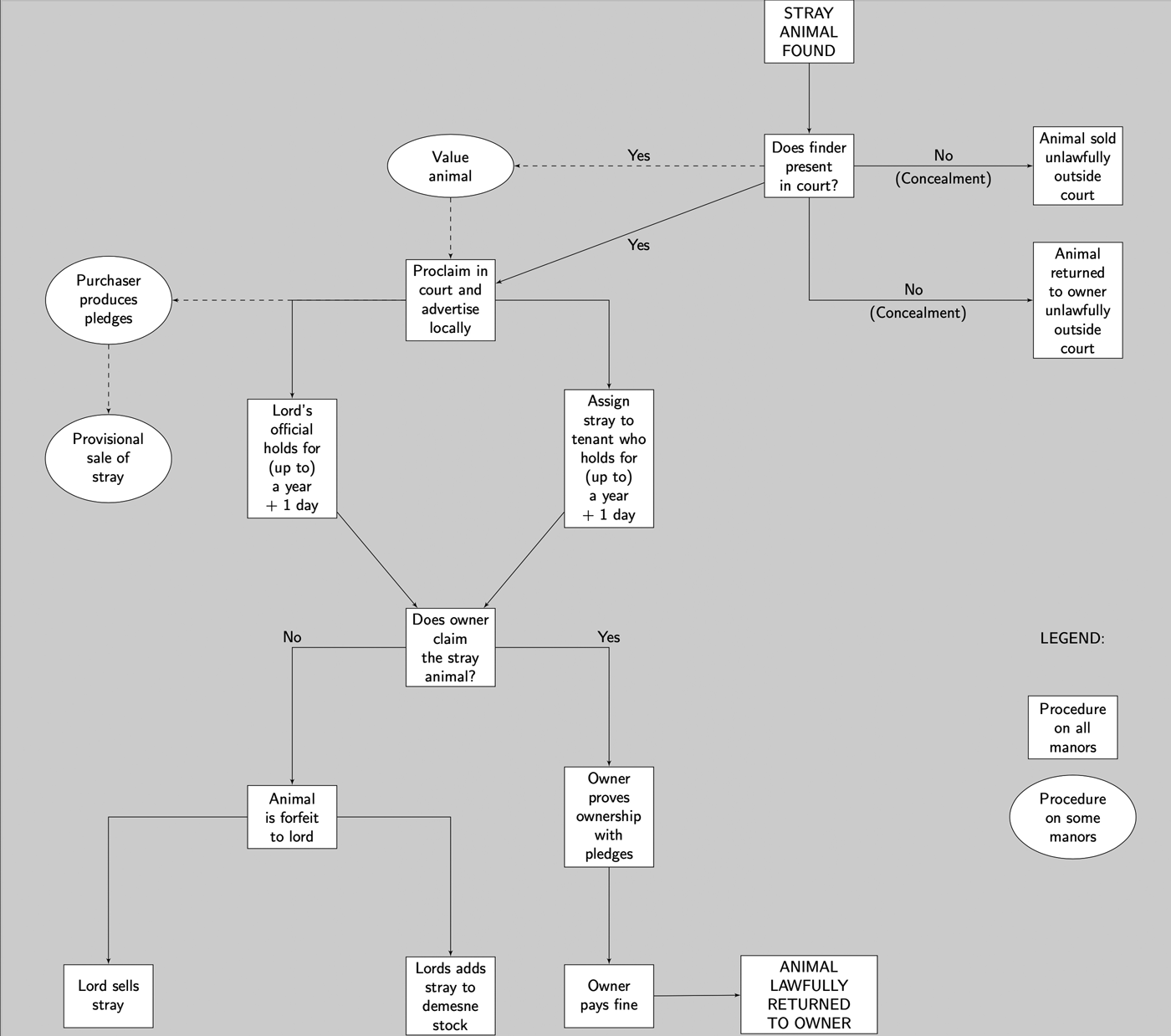

The stray system had four fundamental stages. If the most direct route was followed, a stray was found, presented in court, advertised to neighboring communities, and finally either claimed by its owner or, if unclaimed for year and a day, forfeit to the lord. There were, however, a number of local peculiarities on any given manor as well as multiple opportunities for individuals to try to cheat the system. Both factors could complicate the process. In all cases, the aims of the stray system seem to have been remarkably similar; the core idea was to ensure that the process was sufficiently public and transparent so as to give the owners of lost beasts ample opportunity to find and reclaim them. In this section, we reconstruct the complex processes of the stray system, illustrated in figure 1, as it was administered by manor courts.

Figure 1 Flow Chart of Stray System

The starting point for all cases was for a stray animal to be found within a lordship. This could happen in two ways: either through an ad hoc discovery or via an organized search for unidentified livestock.Footnote 59 In terms of the former, larger animals like horses and oxen were often found on common land. For example, in Wakefield, a suspected stray ox was described as “wandering in the great wood.”Footnote 60 Strays could also be discovered when they appeared on the lord's land, as when pigs “came into the lord's park as strays.”Footnote 61 Some manors also carried out systematic searches for strays. This practice was most prevalent at manors with large waste and/or common lands. For example, at Little Downham, a manor located within the vast fenland around the Isle of Ely, strays were frequently found on the large fen commons. Here, strays were identified through annual drives performed by the community of tenants, where all unclaimed livestock were collected and identified.Footnote 62 At other times, strays were identified not through an actual “roundup” but through a systematic bureaucratic inquiry. The process did not require the physical presence of the animal at a court session, but instead officials simply created a written memorandum documenting the stray's appearance. Officials at Downham made use of both strategies, and juries regularly made inquiries into strays that had recently come onto the manor.Footnote 63 For instance, in 1428, the jury was ordered to “inquire of all strays existing inside this lordship both inside the park and inside the marsh.” These animals were then meant to be presented at the next court.Footnote 64

Once a stray animal was found, the discovery needed to be “registered” at the next session of the manor court.Footnote 65 Sometimes this involved actually bringing the animal to the session, perhaps to ensure that it could be identified by the community. In 1297, Adam Francis was ordered to bring a set of pigs “thought to be strays” to the next court at Wakefield, and similar orders were given at various sessions at this manor between 1307 and 1338.Footnote 66 This public registration of strays had several benefits for lords. Perhaps most importantly, it identified the existence of an asset in their lordship that they could potentially later claim as their own property. It also meant that lords could establish where, and with whom, the animal was being kept, and therefore assign responsibility if an animal was subsequently injured or lost. Such concerns can be seen in inquiries into the death of strays at Worfield and Downham.Footnote 67 At Worfield in 1385, a former reeve was amerced 12d. “for negligence” because “at the time he ought to have guarded . . . an ox.”Footnote 68 Any ambiguity over the provenance of strays created problems. A 1275 case from Wakefield involved a stray that had not been properly taken and presented, so that it was hard to establish who was ultimately responsible for its loss. Initially, the entire township of Walton, a village within the larger manor of Wakefield, was ordered to answer for a stray bullock “that [had been] among them” for around four months between the feast of St. Giles and Christmas but had “afterwards [been] sent away by them.”Footnote 69 In the subsequent court, the township responded to this accusation by arguing that, while the stray had been present “going about in the town and in the fields,” it “was not in anybody's custody who could be made responsible for it.” The stray had then been seized by Ralph Pykard (via his servant) from nearby Normanton, a village outside Wakefield. Ralph's servant was therefore held responsible, allowing the township to be absolved of any wrongdoing.Footnote 70

At several manors, the registration process explicitly involved a valuation of the animals, which could occur even before a beast was necessarily forfeit to the lord.Footnote 71 At Worfield and Downham it is on occasion explicitly stated in the rolls that these valuations were made in court by manorial juries or tenants.Footnote 72 These initial valuations were presumably undertaken so that any loss could be charged to the person holding the animal if a defect of care occurred. For example, in 1413 the reeve of Worfield was ordered to exact from William Preests a fee of 12d., the value of a horse in William's guard that “ran off by negligence of the same William.”Footnote 73

Valuing a stray shortly after it was found also worked to prevent fraud by officials. Accordingly, in 1393, the court at Worfield ordered that a former reeve, Thomas de Rugge, pay 4s. because he had rendered only 7s. for a stray cow that had been valued at 11s. in his account.Footnote 74 Similarly, in 1308 at Wakefield, a grave (a manorial official acting on behalf of the lord) was amerced 24d. for “concealment” because he had not charged himself in the court roll for a stray horse he had purchased for himself or for another stray horse he had sold.Footnote 75 Finally, valuation also helped lords recover the value of strays that fell into the hands of outsiders, either by accident or sometimes by deliberate theft.Footnote 76 For instance, when the jury at Tooting Bec, Surrey, presented that Richard Bradwatere had carried off a stray hog, the lord could order that its value of 16d. be claimed from Richard's goods and chattels. Thus, even if the stray was gone, its value could still be realized.Footnote 77

Despite the registration and valuation mechanisms, the administration of the stray system could be vulnerable to fraud. Court rolls reveal a range of presentments against officials who attempted to circumvent procedure in the manor court in order to profit from stray animals directly.Footnote 78 For instance, at Worfield, in part of a larger set of abuses, Thomas Jenkins, a former reeve, was found to have “seized one cow . . . which came of an outsider or of stray, which . . . he did not present in the court.” Then, “without warrant of the steward or . . . council of the lord [he] delivered the [stray] cow out of the liberty.”Footnote 79 Similarly in 1410 at Downham, the reeve, Thomas Colleson, delivered two stray bullocks “without claim in court.”Footnote 80 In both cases, the lord's officials circumvented the stray system and simply gave the animals back to their original owners, presumably pocketing for themselves the fee owed to the lord.

Officials could also commit fraud by selling stray animals for their own profit. For example, at Wakefield in 1275, the lord's sergeant was found, among other illicit activities, to have sold a stray sheep forfeit to the lord. Thomas Colleson, noted above, committed a similar fraud when he sold, at Ely Market, a foal born of a stray horse.Footnote 81 Defrauding a lord by abusing the stray system was not the preserve of officials alone; tenants also occasionally attempted to cheat the system. The easiest way for a tenant to abuse the system was simply to not report the discovery of strays in court.Footnote 82 At Wakefield, in 1315 and 1316, tenants were presented for taking and concealing stray animals.Footnote 83 Particularly audacious was the case of William de Godeley Jr., who was presented at court for selling a stray ox at Wakefield. When the ox, for reasons left unstated, “returned to William's house,” he sold it for a second time to a second buyer.Footnote 84 Deliberate attempts to circumvent the system could be interpreted as an affront to the lord's authority. Such cases were certainly described in these terms in the court rolls, which ultimately reflect the lord's perspective. However, we might also interpret these cases from the tenants’ point of view.

In cases like the ones discussed above, when a lord's official circumvented the manor court but still returned a stray animal to its original owner, the owner obviously stood to benefit from the evasion. In such a scenario, an owner likely colluded with the official and presumably paid a smaller fee than a lord would exact, or even no fee at all, to get their animal back. Individual tenants and officials would obviously stand to profit from such an arrangement. However, concealment would have had further-reaching negative effects on trust and cohesion within the larger village community and beyond. Ultimately, the stray system was designed to return lost animals to their original owners. For that to work, it needed to be both public and transparent. Concealment, especially if the animal was sold outside the stray system by the concealer, would have deprived a tenant of the ability to reclaim an important capital asset and ultimately undermined the integrity of the stray system.

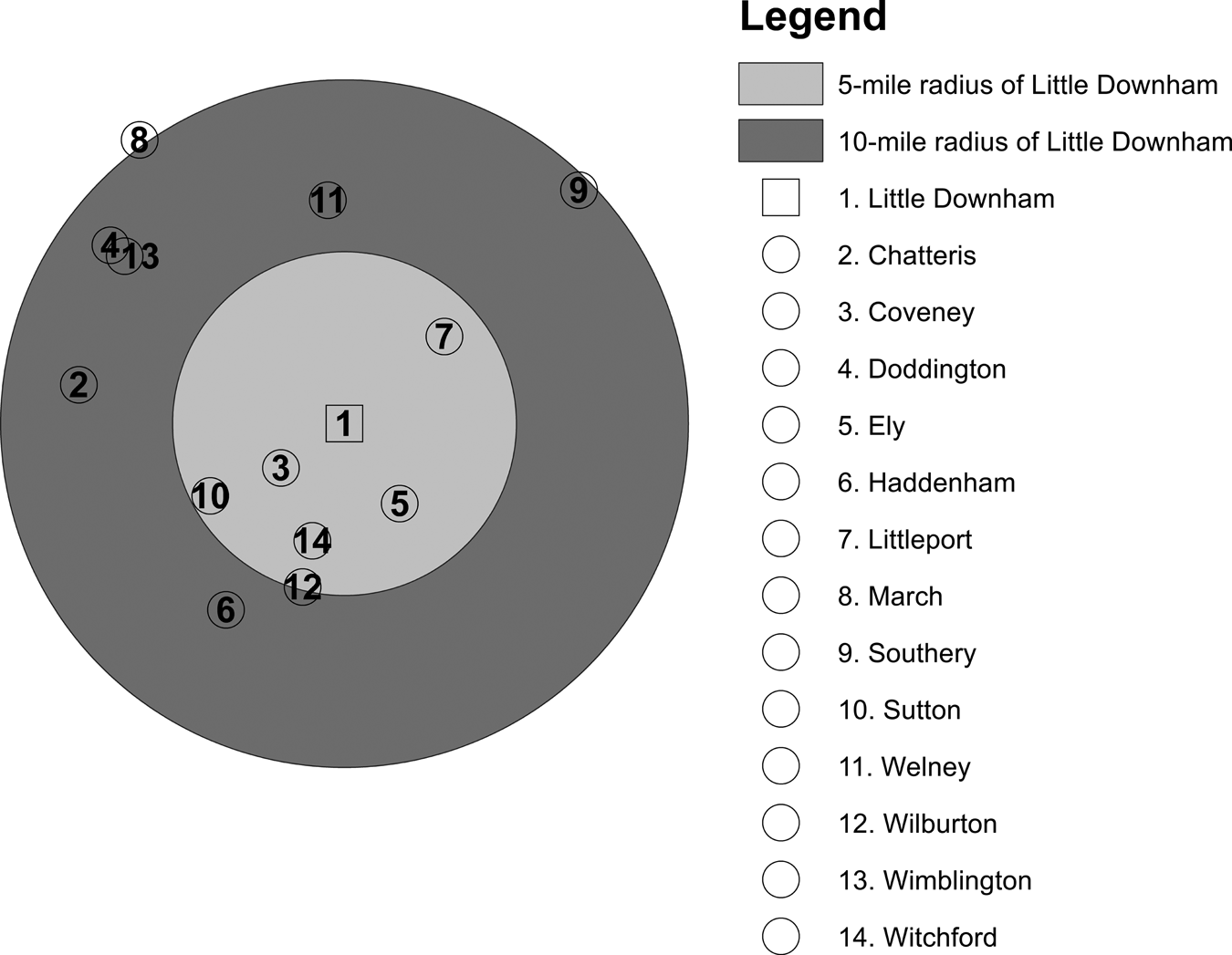

Once an animal was brought to the court and registered as stray, the system required it to be “proclaimed.” This essentially meant that news of the discovery had to be “advertised” or disseminated both inside the community and in other nearby public forums, according to the law. This was the fundamental aspect of the stray system that allowed claimants to locate and recover their lost animals. How did the proclaiming process work? While most court roll entries simply state that animals “are to be proclaimed,”Footnote 85 “were proclaimed,”Footnote 86 or “hav[e] been proclaimed,”Footnote 87 at Tottenham and Alrewas some entries are more prescriptive and explicitly mimic the precise language of the franchisal law, stating that proclamations should occur “in the market place and church.”Footnote 88 At the latter manor, one stray foal was claimed by the bailiff of the precentor of Lichfield after being “cried twice in Lichfield fair and three times in the church.”Footnote 89 Similarly, in 1327, the court at Wakefield ordered that Thomas Alayn, into whose care a stray steer was entrusted, was “to have it proclaimed for three days in the Wakefield market.”Footnote 90 In 1358, at Bradford, a stray was said to have been “multiple times proclaimed everywhere,”Footnote 91 while, in 1444, at Elmley Castle, strays had been proclaimed “in various foreign districts.”Footnote 92 These proclamations were effective in spreading news about strays, as the information traveled across a relatively wide geographical area. Figure 2 illustrates the impressive reach of these advertisements by plotting the home villages of individuals who successfully claimed strays at Little Downham's manor court. As can be seen, claimants came from as far as ten miles away to recover their lost animals. This was a significant distance in the medieval world, the round trip requiring a whole day's travel.Footnote 93

Figure 2 Home Villages of Claimants to Strays at Little Downham's Manor Court. Sources: CUL, EDR, C11/1/2-3, C11/2/4-6.

After a stray beast had been proclaimed, it entered a period of legal limbo where no one person could claim to truly be its owner. Stray animals remained in this stage of the system until they were either claimed or were forfeit to the lord after a year and a day. As one can imagine, there were practical concerns around maintaining an animal during this period. This responsibility was shared by the lord and the community. On some manors, the lord's officials were responsible for maintaining the animals, while on others tenants actively collaborated with lords to care for the beasts and uphold the integrity of the stray system. At Downham, the custody of strays seems to have been largely the remit of seigniorial officials, as strays were held in the bishop's 250-acre park.Footnote 94 At Worfield, in contrast, strays were frequently assigned to individual tenants. Of the 386 strays whose guardians can be traced in the court rolls for 1353–1450, just under 80 percent were looked after by tenants rather than officials. Guardianship was spread throughout the tenant community; over 157 individuals cared for two animals each, on average.Footnote 95 This phenomenon of entrusting strays to individual tenants can also be seen at Wakefield, Willington, Bradford, and Elmley Castle.Footnote 96 Having custody of a stray did not mean that the tenant had legal ownership of the animal, and courts clearly recognized this distinction.Footnote 97

For claimants to get their animal back, they had to provide certain assurances. Strays had to be “proved” or “haymalded” by the original owner as part of a public process. Typically, the claimant appeared in court with between three and twelve “hands”: individuals who would vouch that the stray indeed belonged to the person claiming it.Footnote 98 As with many medieval legal processes, these hands had to be “trustworthy” men.Footnote 99 For example, in 1390 at Tottenham Bruces, Thomas Benworth of Walthamstow came with “true men of the neighbourhood” to “prove” his calf.Footnote 100 This process could also be carried out by an agent acting on behalf of the actual claimant, such as a servant acting for a master, or a family member acting for a relative who was perhaps a minor.Footnote 101 In addition to proving ownership, claimants were sometimes required to demonstrate that the stray animal in question had not been stolen or been in the possession of thieves while out of their care.Footnote 102

The only legally legitimate way to recover a stray animal was through the manor court. Circumvention of the court system, even by the original owner, was punishable by amercement. Simply put, once a stray had been discovered and entered the system, an owner could not just go and take it back. Claimants had to recover their animals through the stray system. This was designed to prevent illegitimate claims, but perhaps most importantly, to protect the transparency upon which the system depended. A number of cases illustrate this point.Footnote 103 In an unusually detailed example from Wakefield in 1331, William, son of William del Hirst, was arraigned for taking two stray mares held in the custody of Thomas de Stainland. William admitted that he had indeed taken the strays but claimed that his actions were permissible, as the two mares were his property. Nevertheless, because he had circumvented the system, he was fined 12d. for taking the mares without the bailiff's license.Footnote 104

Strays could be returned to owners outside of an actual court sitting, but this still had to be approved by a seigniorial official.Footnote 105 Even once strays were returned, several courts had procedures to ensure that if a second claimant subsequently appeared with a genuine claim, the owner could still recover the property. This was typically done through a pledging system, where the original claimant had to find one or more pledges. Similar to the hands discussed above, pledges were “trustworthy” men from the community. Rather than simply vouching for the legitimacy of an individual's claim to a stray, as hands did, a pledge was made responsible for either producing the animal or providing its value, if another (legitimate) claimant came forward within a year and a day of the stray's original discovery.Footnote 106 Therefore, a claimant's property rights were always protected by the system, even if the court had initially allowed another to (illegitimately) recover a stray, so long as a claim was made within a year and a day.

Once the myriad stages of the stray system are broken down, it becomes clear that it was heavily biased toward claimants who could rely on a public system not only to find and secure a lost animal but also to protect largely unalienable rights to claim the stray within a 366-day window. Despite these rights, a significant number of stray animals went unclaimed. Evidence from Downham, where it is possible to track animals over time, reveals that of 299 strays that can be tracked between 1365 and 1449, around 57 percent were not claimed.Footnote 107 When this happened, unclaimed animals became the property of the lord. In several cases, lords then took the animals into their own hands for their own uses. Working animals were often taken for the lord's demesne. Court rolls sometimes illuminate such transfers, as in 1274 at Wakefield when two horses and a cow went unclaimed and were subsequently ordered to be placed with the earl's stock.Footnote 108 Account evidence reveals that the acquisition of strays augmented other seigniorial perquisites, like heriots (a death due, usually tenants’ best beast, owed to their lord), and provided lords with a significant source of demesne livestock.Footnote 109 When lords put an acquired stray draft animal to work on their farm, it often displaced an incumbent of lower quality.Footnote 110 When non-working animals fell to the lord, they were sometimes simply consumed. At Downham in 1450, a black bullock valued at an exceptional 9s. 6d. fell to the lord and was slaughtered “in hospitality of the lord to the use and welcome of the lord.”Footnote 111 As Downham was a rural retreat of the bishop of Ely, the beast was likely slaughtered for the bishop and his guests.

Lords often chose simply to realize the value of acquired strays through sale. This option presumably offered greater flexibility, especially as many of the stray draft animals acquired by lords would have been of lower quality than those employed in demesne agriculture.Footnote 112 Indeed, many of the stray horses that fell to demesnes would have been surplus to requirements and were therefore quickly “flipped” for cash.Footnote 113 At some manors, such as Worfield and Bradford, sale seems to have been almost universally favored. At Worfield, sales are described as being made “by the steward” and “in full court.”Footnote 114 This means that sales of stray livestock were public, ensuring that tenants had first access to the unclaimed strays that had fallen to the lord. At other manors, sales seem to have been managed differently. At Elmley Castle, strays were often sold to the tenants who had guarded them for the requisite 366-day claiming period. The possibility of securing permanent ownership perhaps suggests an incentive for tenants to maintain strays well.Footnote 115

Bradford saw this arrangement taken a stage further, with stray animals being sold before the end of the 366-day period and thus being placed in the custody of these purchasers. However, the sale explicitly did not obviate the claim of the original owner. Much as when strays were claimed, purchasers were required to provide pledges to ensure that they would produce the animal or its value if a claimant later appeared within the allotted time period.Footnote 116 At the same time, payment to the lord could be delayed until after the 366-day period had elapsed, meaning that purchasers did not lose their investment.Footnote 117 Tenants at Bradford seem to have been allowed right of first refusal for animals found as strays. In an example from 1353, three stray foals were given to the Brothers of Pontefract because “none will buy them.”Footnote 118 Of course, the difficulty of finding a buyer in this case may well have been an effect of dampened demand and economic uncertainty in the wake of the Black Death. On rare occasions, strays were sold in bulk. An entrepreneurial individual might have been able to lease or purchase the right to buy prospective strays, as seemingly happened at Wakefield when all the strays found in the accounting year 1350–51 were sold in advance to William Mirefield for a flat sum of 10s.Footnote 119 This particular sale also may have been an exceptional response in the aftermath of plague, but other bulk sales were not unheard of, as was the case at Downham in 1452 when twelve strays were sold to Roger Davy, described as “of Ely.”Footnote 120

Overall, however, the discussion above suggests two significant conclusions about the exercise of franchisal rights to strays in late medieval England. Firstly, there was a robust and sophisticated procedure that was heavily biased toward legitimate claimants, ensuring that any owners had the right to claim their stray within the year and a day, as stipulated in the franchise. Courts worked to ensure that strays were publicly registered and then widely proclaimed within the 366-day period. The system also punished both officials and tenants who tried to profit illicitly from animals or simply failed to guard them properly. The rights of claimants were protected in all circumstances.

Secondly, this system necessitated the significant involvement of a large number of the lord's tenants. These obviously included the seigniorial officials, drawn from among the peasantry, who managed strays, but it also extended beyond this to encompass the broader community. In terms of involvement in the stray system, tenants not only utilized the court to present strays but also acted as jurors or a general collective to assign valuations to these animals. They often became responsible for the custody of the animals over the 366-day claiming period. Moreover, this system provided the additional benefit of allowing tenants the opportunity to purchase unclaimed strays, giving community members access to a relatively cheap stock of animals. In this way, the system is akin to that described by Johnson for wreck courts, where the system provided a way to legitimately realize the value of found objects.Footnote 121

Of course, it could be argued that there were more efficient ways to provide the public good of policing strays. One hypothetical alternative would be a finders-keepers model, where those who found a stray simply got to keep the animal. Another would have been a system at the village level that cut out the lord completely. In this second scenario, there would have been no need to pay a fee to the lord for custody upon a claim, nor would it have been necessary to buy strays from the lord. Under such a hypothetical situation, the lord would not have had the ability to take strays for his own stock or consumption. However, even in the unlikely scenario that lords would have allowed such an undercutting of their authority, a solely village-run institution would not have offered the protection guaranteed by the public process of the lord's court and its ability to coerce those who flouted the system through financial penalties. While other systems could have provided protection against destruction of crops by animals, they could not simultaneously preserve the property rights of the original owner.

Could Lords Profit from The Stray System?

Our analysis suggests that the stray system protected the property rights of tenants, serving their purposes as much as their lord's. However, this conclusion raises an obvious question: did administering the system bring lords a windfall of profits? When strays were claimed back by their owners, lords received a fee. In addition, if animals went unclaimed after the 366-day period, lords, either by adding the animal to their stock or by selling it, realized its value.

But any such income derived from the stray system needs to be weighed against the costs of administering it. This section addresses this issue with a hypothetical exercise, asking whether it would have been possible for lords to turn a profit on the stray system. We illustrate that, due to a range of constraints imposed by the legal institutions underpinning the stray system, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for most lords to profit from the system even if they had wanted to. To illustrate we conceive of a situation where lords did try to profit from the system. What would this look like? What conditions would have to be met for lords to gain in a meaningful way from wielding the franchise of strays?

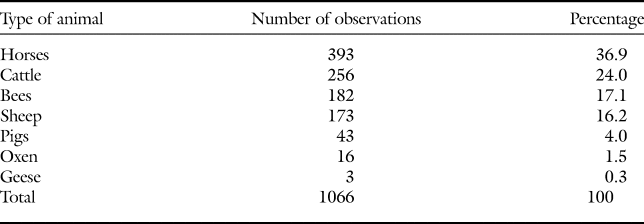

In this exercise, we focus only on stray horses, which are the best available test of the stray system. Within the wide range of livestock that came into the system, horses appeared most frequently, and accordingly they represent the largest group in our sample. Out of our total of 1,066 stray observations, 393 were horses, comprising 36.9 percent of the total sample (see table 1). Cattle are also a large group (256 animals accounting for 24 percent of the total), but the great range of types and variations in maturity of these beasts makes any quantification impossible. Horses, on the other hand, were a rather more homogenous group of animals, and there is sufficient surviving quantitative evidence to model both lords’ costs in maintaining horses and the potential payoff they could have received if the animals ultimately fell to them. Oxen could be modeled similarly, but the sixteen observations in the sample are too few to draw meaningful conclusions. Horses were also a more expensive beast to buy and keep than sheep or pigs and therefore are the obvious case study to pursue here.Footnote 122

Table 1 Composition of Stray Animals

Sources: SA, P314/W/1/1/31-303; CUL, EDR, C11/1/2-3, C11/2/4-6; Baildon, Wakefield 1274–29; Baildon, Wakefield 1297–1309; Lister, Wakefield 1313–1316; Lister, Wakefield 1315–1317; Walker, Wakefield 1322–1331; Helen M. Jewell, The Court Rolls of the Manor of Wakefield from September 1348 to September 1350 (Leeds, 1981); Walker, Wakefield, 1331 to 1333; Habberjam, O'Regan and Hale, Wakefield 1350 to 1352; Troup, Wakefield 1338 to 1340; TNA, DL 30/129/1957; Oram, Tottenham 1377–1399; Jamieson Transcriptions: BARS, R Box 212; London County Council, Tooting Beck; British Library, Additional MSS. 63428-51; SROI, HA116/3/19/1/2-5.

The costs that lords would have incurred in keeping a stray horse for the requisite 366-day period could include a range of components. The largest by far would have been fodder, and there were also other obvious costs in maintaining a working animal. Horses were frequently shod with metal shoes, and the stables or barns in which they were kept had to be maintained. On a more theoretical level, one might also figure depreciation into the equation. The year and a day that lords were required to keep stray animals was a significant portion of a horse's effective working life of around ten years, so the animals clearly lost value as they aged.Footnote 123

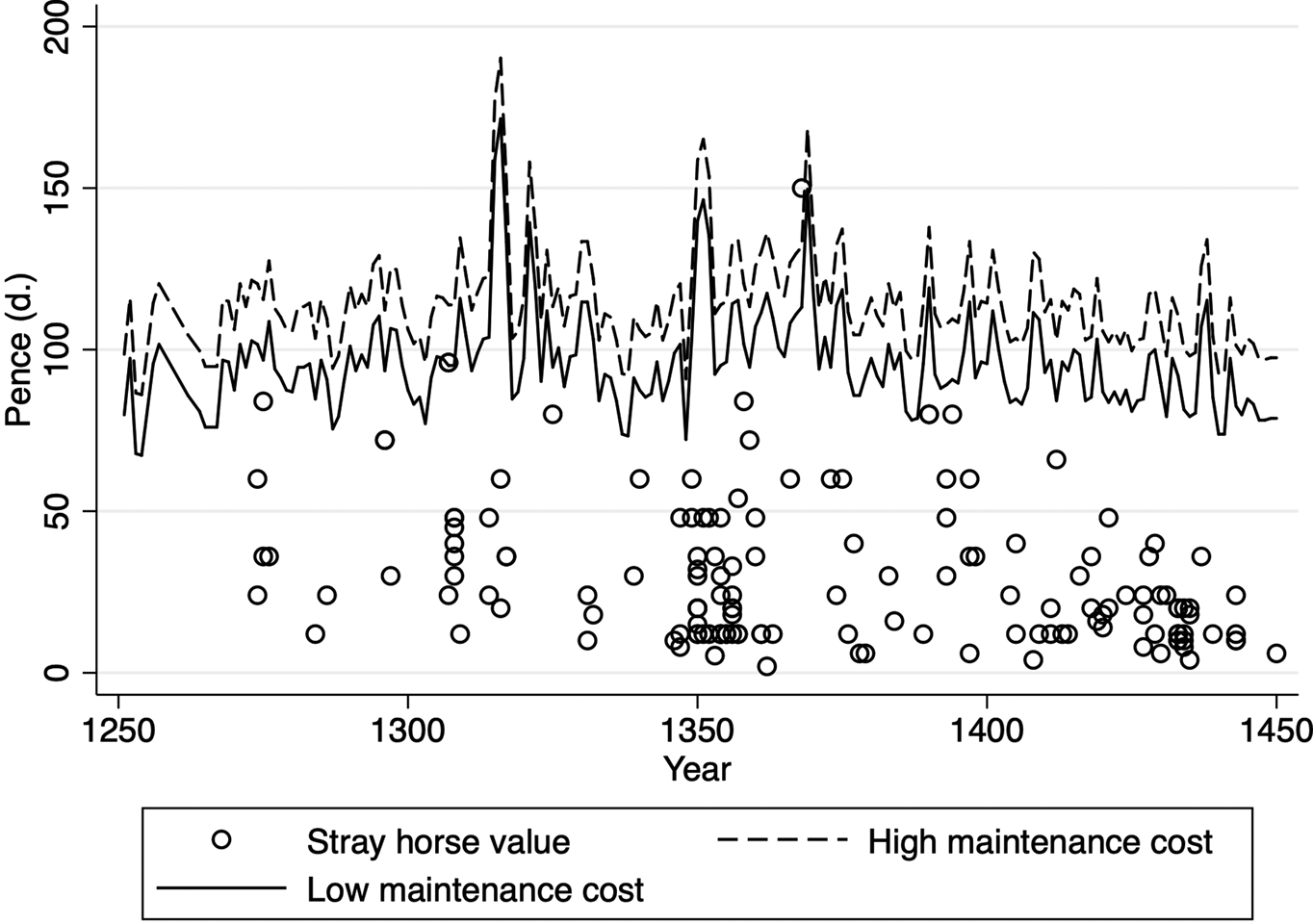

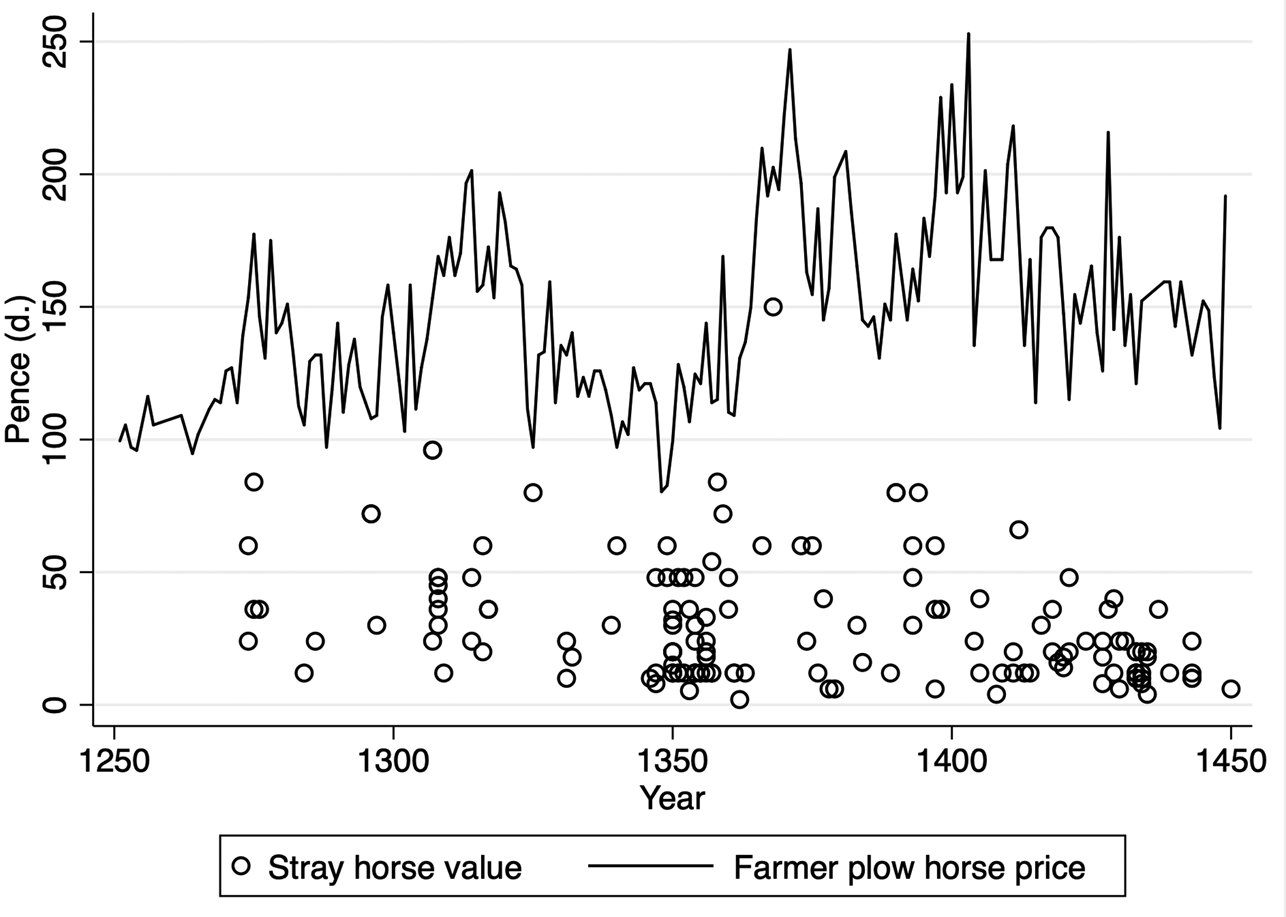

Taking all these elements into account, we have created two maintenance cost estimates for every year between 1250 and 1450, a high estimate that includes all the components discussed above, and a low or bare-bones estimate that only includes fodder costs and is basically the amount required to simply keep an animal alive. The specific composition of each estimate and the relevant methodological concerns are described in Appendix A. These are illustrated, along with discrete values of individual stray horses, in figure 3. Over the two centuries from 1250 to 1450, the average cost of maintaining a horse for 366 days would have been around 115d. at a high level and 102d. at the bare-bones level of subsistence. As our maintenance estimates are driven by fluctuating grain prices, maintenance costs were substantially higher in the famine years of 1315–1317 and following the Black Death in 1350–1352. A third spike is observed in 1369, which Bruce Campbell has attributed to a “combination of dearth and plague” in a period of bad harvests and recurring plague episodes.Footnote 124 In any event, the cost of maintaining a stray horse was centered around 100d., or 8s. 4d., for most of our period. That amount would have been equivalent to forty days’ wages for a semi-skilled worker, such as a thatcher, in 1300 when such a job paid 2.5d. per day, or twenty-two days’ pay in 1400 when wages had climbed to 4.5d.Footnote 125

Figure 3 Comparison of Stray Horse Values with “High” and “Low/Bare Bones” Maintenance Costs. Sources: Stray values: SA, P314/W/1/1/31-303; Baildon, Wakefield 1274–1297; Baildon, Wakefield 1297–1309; Lister, Wakefield 1313–1316; Lister, Wakefield 1315–1317; Walker, Wakefield 1322–1331; Jewell, Wakefield 1348 to 1350; Walker, Wakefield 1331 to 1333; Habberjam, O'Regan and Hale, Wakefield 1350 to 1352; Troup, Wakefield 1338 to 1340; TNA, DL 30/129/1957; Oram, Tottenham 1377–1399; Jamieson Transcriptions, BARS, R Box 212; London County Council, Tooting Beck. Maintenance costs: see Appendix A.

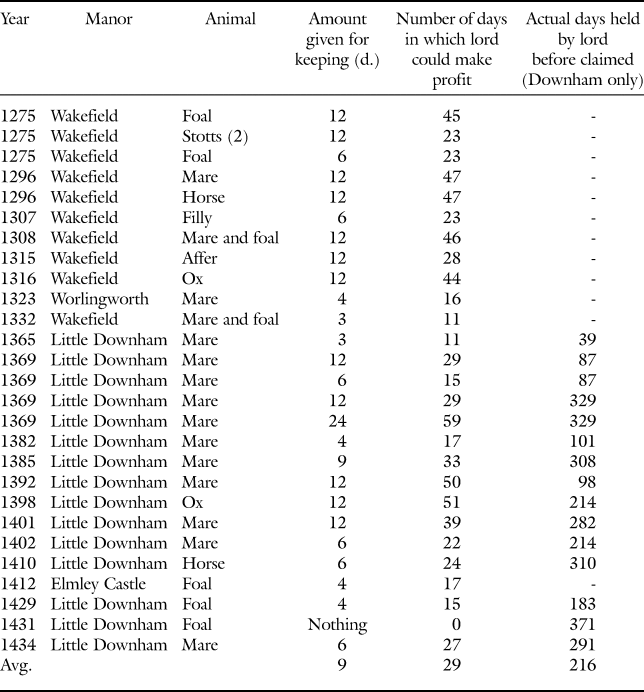

To calculate a cost/benefit analysis, the lords’ outlays need to be balanced against the income they could generate through the stray system. The first revenue channel was the fines that claimants paid to retrieve their stray animals from the lord. The court rolls unfortunately do not record this information systemically, but we were able to glean twenty-eight observations, which appear in table 2. As can be seen, these retrieval fines tend to cluster in distinct groups. Claimants usually paid either 3d., 6d., or 12d., to reclaim their animals. These rates are typical of the wider range of manor court fines and amercements at the time. When described in the court rolls, the fines are justified as either for keeping the animal or, more generally, as a fee for claiming.Footnote 126 What is obvious is that these fines are so low that it would have been difficult for lords to make any significant profit from them. Table 2 compares the fines paid by claimants against lords’ maintenance costs. The table provides the number of days of maintenance that any individual fine would have financed. As can be seen, these fines, on average, would have covered only twenty-nine days’ maintenance costs, and most strays spent significantly more time under the lord's care. Fortunately, Downham's court rolls provide enough information to estimate the number of days that some stray horses spent in the lord's care before being claimed. In all fifteen cases, the lord held the animal for significantly longer than would have been profitable. A case of 1370 described in the Year Books supports this view. A plaintiff (clearly of high status, if not a lord himself) sued a certain lord for refusing to return his stray mule. The defendant argued that he had retained the mule justly, as the fee of 2s. offered by the plaintiff (through his bailiff) “was too little, for the [month] that the mule was in the defendant‘s keeping.”Footnote 127 This fine of 2s. is much greater than the average fine of 9d., yet it was argued that the amount was still insufficient to cover the costs of maintaining this particular mule.

Table 2 Stray Fines in Comparison to Maintenance Costs

Sources: Baildon, Wakefield 1274–1297; Baildon, Wakefield 1297–1309; Lister, Wakefield 1313–1316; Lister, Wakefield 1315–1317; Walker, Wakefield 1331 to 1333; CUL, EDR, C11/1/2-3, C11/2/4-6; SROI, HA116/3/19/1/2-5; Field, Elmley Castle 1347–1564.

If lords could not generate any significant revenue from fining claimants, the only remaining profit channel would be to benefit in some way from realizing the value of unclaimed strays. Figure 3 compares all of the values of stray horses contained in our sample against the high and low annual maintenance cost estimates. This analysis reveals that both maintenance cost estimates consistently exceeded the values of stray horses, with very few exceptions, over the duration of our study. Even the very conservative bare-bones cost, which includes only enough food to keep the animal alive and assumes no loss in value over the time it was held, is consistently higher than the values that lords could expect to realize from any single stray horse. Put simply, the costs of maintaining a stray horse for 366 days would almost inevitably outstrip the animal's value, whether a lord ultimately decided to keep the beast for his demesne or to sell it for cash. In this paradigm, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for lords to profit in any meaningful way from the stray system. The one real exception to this pattern is the horse discussed above, worth an abnormally high 13s. 4d., which appeared at Tottenham Pembrokes in 1393.Footnote 128 If this horse had gone unclaimed, the joint lords of the manor would have stood to make a profit of around 4s.Footnote 129 However, the horse subsequently escaped into a neighboring lordship and was seized by this other manor's bailiff. This particular horse was likely an unusually valuable stray, as Tottenham's clerk took the unusual step of noting that the lord's counsel should be sought on this matter.

Figure 4 plots the values of stray horses in our sample against the average national price for plow horses, as compiled by David Farmer.Footnote 130 It is immediately apparent that the values of the strays in our sample were not only significantly less than the annual cost of their upkeep but also much lower than cost of the average plow horse. How can we explain the persistently low values of these animals? The most obvious reason is that they were simply of low quality. Many examples from the court rolls support this conclusion. Stray horses were often described as “infirm,” “disabled,” or “debilitated,” and in 1331 the clerk at Wakefield noted that a foal was sold for 10d., a price that was “so little because [the foal] is of no value.”Footnote 131 Similar indications of low quality can be found for other animals, with a range of other beasts also described as “debilitated” as well as “lame” and “weakened.”Footnote 132 Indeed, the jury at Worfield noted a sheep had been valued at 4d., “and not more because [it is] debilitated.”Footnote 133 More colorful examples include a pig at Wakefield described as “leprous”Footnote 134 and a bull at Bradford as “insane.”Footnote 135 The low quality was potentially a selection effect. Owners may have released worthless or diseased livestock rather than going to the bother of slaughtering them, or at least expended little effort to recapture such low-quality animals if they escaped.

Figure 4 Comparison of Stray Horse Values with Farmer's Annual Plow Horse Price Series. Sources: Stray values: see figure 3. Plow horse prices: Farmer, “Prices and Wages,” in The Agrarian History of England and Wales, vol. 2, 1042–1350, ed. H. E. Hallam and Joan Thirsk (Cambridge, 1986), 745–55, 799–806; Farmer, “Prices and Wages, 1350–1500,” in The Agrarian History of England and Wales, vol. 3, 1348–1500, ed. Edward Miller (Cambridge, 1991), 455–61, 508–12.

The very nature of these transactions would have also pushed values down, as these were essentially “fire sales.” Having already borne the high costs of upkeep for a year and a day, lords would have been highly motivated to get rid of strays quickly, pushing them into a forced sale. Similarly, as discussed above, the values recorded in the court rolls were most frequently determined by tenant juries when strays first appeared and were registered with the manor court. These juries could have deliberately undervalued stray beasts and would have had reasonably strong incentives to do so, as tenants often ended up purchasing unclaimed stray animals from the lord. But, even if the values of these stray animals were not market prices, they were the sale prices. The value determined in the registration process was essentially binding, and lords, if they sold strays that fell to them, almost invariably received the registered price.Footnote 136

Thus, lords ultimately lost money through the stray system because maintenance costs would always outstrip whatever they could make from either fines paid by claimants or by selling or keeping the stray beasts that fell into their hands. Of course, horses are only one type of stray animal, and non-working livestock would have produced goods like wool and milk that could have offset the cost of their maintenance. Similarly, draft beasts had a potential value in the work they could do. However, as demesne farms operated on full stocking regimes, there was likely little value in having an extra and often unsuitable horse to contribute to farm operations.Footnote 137 More generally, the fact that lords often did not maintain strays themselves for the 366-day period but frequently assigned them to tenants suggests that they did not see a significant opportunity for profit. As a process that essentially allowed lords to collect low-quality animals that were unsuited for demesne agriculture and unable to realize a good price at sale after a long period of costly maintenance, the stray system can in no way be seen as being primarily a source of revenue for lords.

Conclusion

We started with a curious narrative about eight animals that had appeared in a small village community in fourteenth-century Cambridgeshire. We hope to have demonstrated that this story is much more consequential than it might first appear. Stray animals were an ever-present feature of rural life in the Middle Ages, and administering scores of such animals had far-reaching implications for the society and economy of late medieval England.

The right to take strays was granted, via formal franchise, by the crown to the most privileged lords. However, on the ground, it was effectively a system run by some of the humblest individuals. Peasants were the actors who found, registered, advertised, and cared for stray beasts. They were the owners who came and claimed their lost animals as well as the people who often ended up buying those whose owners never came forward. This system helped secure and circulate a stock of cheap animals that, while perhaps unsuitable for the demands of commercial demesne agriculture, could be productively utilized by peasants.Footnote 138 In this way, the stray system aided the broader pastoral economy of late medieval England by catalyzing the circulation of animals among the peasantry.

The system had two clear purposes: to protect the property rights of those who had lost animals and to safeguard the agricultural land upon which the whole country depended for its livelihood. These ends were achieved by cooperation between lords and tenants. Lords channeled royal privileges to the local community and utilized their manor courts to ensure the transparent administration of the system that was vital to protecting claimants’ rights. In a society where individuals could, and often did, resort to violence to settle disputes,Footnote 139 such transparency was necessary to maintain social cohesion.

Did lords exercise the franchise of stray for profit? Or did they exercise it for the benefit of the community? We have demonstrated that it was impossible for lords to have profited from the stray system in any meaningful way. Our examination of the costs and potential benefits involved in the management of stray horses proves this point. The fines that claimants paid to lords to reclaim their lost animals were simply too low to have generated any revenue. Further, lords would have spent more on maintaining most strays than they could recoup even if a beast went unclaimed and ultimately fell into their hands. This explains why lords did not attempt to benefit financially from their franchise. Instead, they used their privilege to provide an integral public good to the communities over which they had lordship.

What does our study of stray animals suggest about the role of manorial institutions and lord-tenant relations in late medieval England? Our examination of the stray system supports the growing corpus of revisionist literature that has emphasized the facilitative role played by manorial structures in peasant communities. It demonstrates one way in which lords used their manor courts to coordinate a cooperative solution to a pressing problem for their tenants, rather than as a tool for direct expropriation. The stray system illustrates how seigniorial lords, and their institutions, helped solve a problem that would have been difficult for tenants to resolve by themselves. The reasons for this were not necessarily altruistic. Lords were reliant on a productive peasantry to fill their fields with able-bodied laborers or their coffers with rents—or both. Using their manor courts to provide an essential public good, as they did by administering the stray system, simply made economic sense. While lord-tenant relationships could be, and often were, conflictual, our examination of the stray system illustrates how the manor court could also facilitate cooperation. From this perspective, we might think of the manor court as the glue that allowed for social cohesion and the pursuit of mutual economic benefits.

Appendix A

Calculating Maintenance Costs for Medieval Draft Animals

We attempt here an estimate of how much it would have cost to maintain working horses in late medieval England. As discussed in the text, many variables are involved in such an estimation, but we have a wealth of data from which to judge the matter.

Many of these components have been meticulously calculated by John Langdon.Footnote 140 As Langdon outlines, there are three main components to consider when calculating these costs:

1. Food and fodder costs. These usually comprised some combination of hay and other more expensive and more calorific grains like oats, but also straw and grass pasture.

2. Other maintenance costs. These would include costs for shoeing, harnessing, and stabling.

3. Depreciation. This component considers the average loss in value of a working animal over time.

We have followed Langdon's methodology except that, while he used fixed average prices for food and fodder costs, we have utilized annually variable grain prices drawn from the work of David Farmer to compute a more accurate annual cost series.Footnote 141

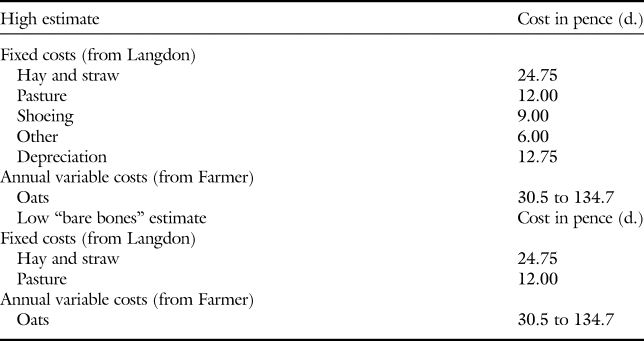

Table A1 Draft Horse Maintenance Cost Estimates

Appendix B

Court Roll Sample and Stray Horse Value Sample

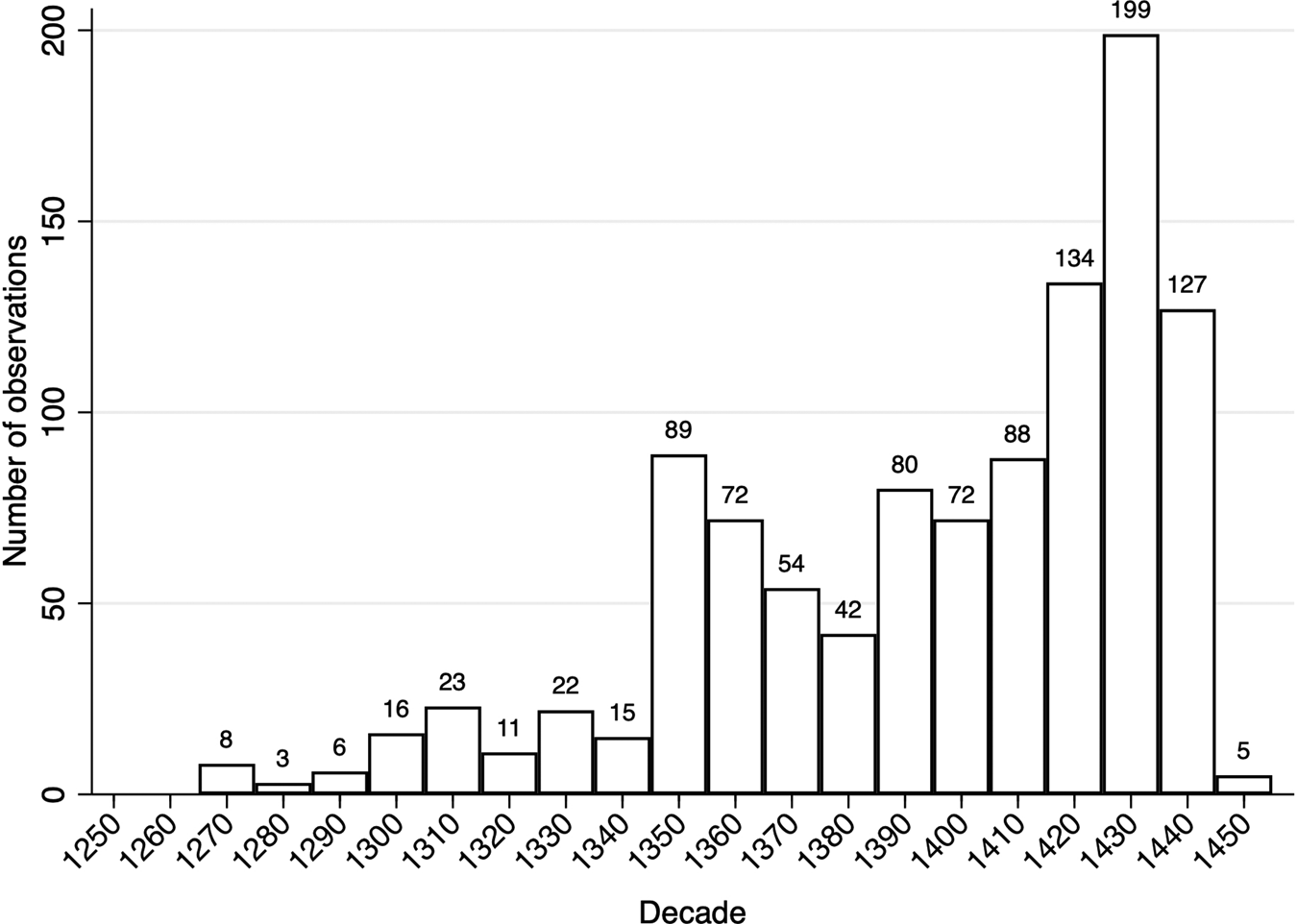

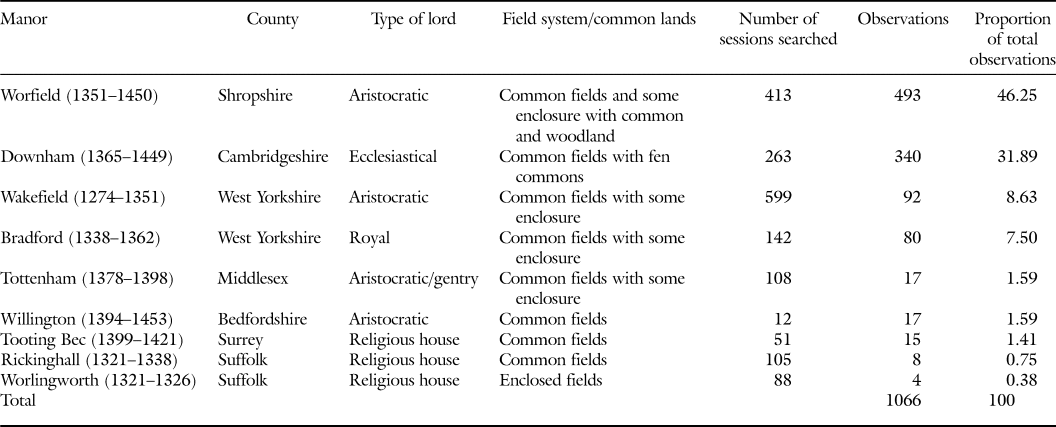

The empirical basis for this article rests on a corpus of 1,066 observations of stray animals based on a sample of manorial court rolls spanning the years 1274 to 1453 and containing a total of 1,781 court sessions. As table B1 illustrates, these sessions are drawn from nine different manors. The sample is not balanced, with the core manors of Worfield and Little Downham making up a large proportion of the total observations of strays. Similarly, there is a bias toward the post–Black Death period, with the majority of observations coming from the 1350s onward, as seen in figure B1.

Figure B1 Frequency of Stray Observations by Decade. Sources: See table B1.

Table B1 Manors Sampled

The sample does have several advantages. It encompasses a wide variety of regions including the North, West Midlands, Home Counties, and East Anglia. It thus captures regions traditionally seen as more commercialized, such as the Thames Basin area around London and East Anglia along with less commercialized areas such as the North East and West Midlands. There is some bias in the sample towards manors with open-field systems and commons. There are two likely explanations for this. First, animals were more likely to escape and therefore stray on such manors, and second, strays posed a more significant threat to crops on open-field manors and therefore tenants had more incentive to catch them. The sample also captures a variety of more powerful lords, including manors held by a mixture of royal, aristocratic, ecclesiastical, and monastic lords.

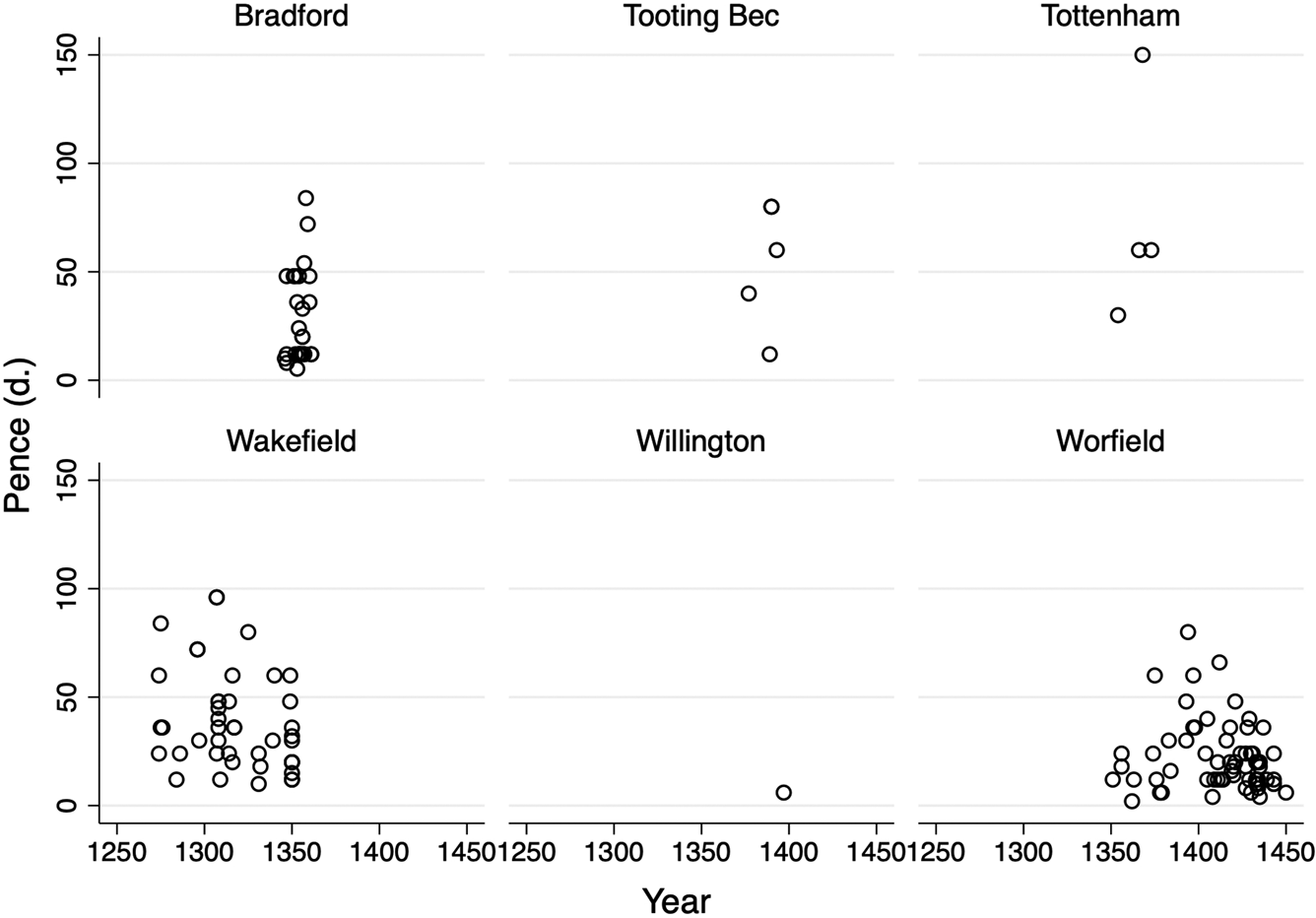

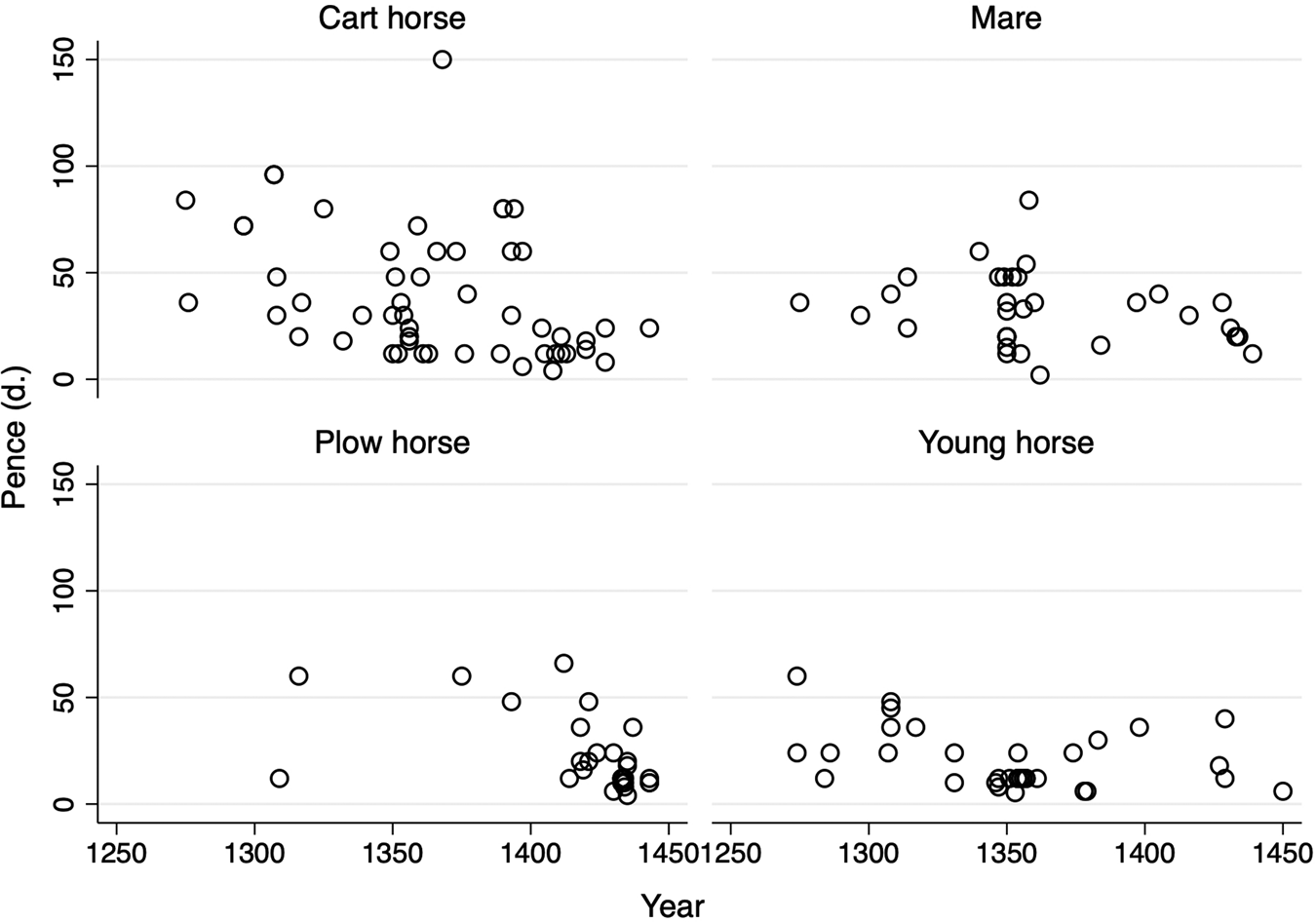

A subsection of the sample was used to provide values for stray horses. The sample consists of the values reported for stray horses from six manors as shown in figure B2. There are no observations from Downham, Rickinghall, or Worlingworth in the horse subsample. Downham's court rolls provided no values for stray animals, and no horses were among the strays reported with values at Rickinghall or Worlingworth. Wakefield accounts for the majority of the pre–Black Death horse observations and Worfield for the majority of the sample after 1350. As figure B3 demonstrates, the sample is well balanced in terms of horse type, with all types of horses except plow horses being found relatively uniformly throughout the period examined.

Figure B2 Composition of Stray Horse Sample by Manor. Sources: Worfield: Shropshire Archives, P314/W/1/1/31-303. Wakefield: Baildon, Wakefield 1274–1297; Baildon, Wakefield 1297–1309; Lister, Wakefield 1313–1316; Lister, Wakefield 1315–1317; Walker, Wakefield 1322–1331; Jewell, Wakefield, 1348 to 1350; Walker, Wakefield, 1331 to 1333; Habberjam, O'Regan, and Hale, Wakefield 1350 to 1352; Troup, Wakefield 1338 to 1340. Bradford: TNA, DL 30/129/1957. Tottenham: Oram, Tottenham 1377–1399. Willington: Jamieson Transcriptions: BARS, R Box 212. Tooting Bec: London County Council, Tooting Beck.

Figure B3 Composition of Stray Horse Sample by Horse Type. Sources: See figure B2.

Despite the unbalanced nature of our data, the sample is well suited to the quantitative exercise conducted here, as we make no claims about the average cost or value of animals but rather use each observation individually.