No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

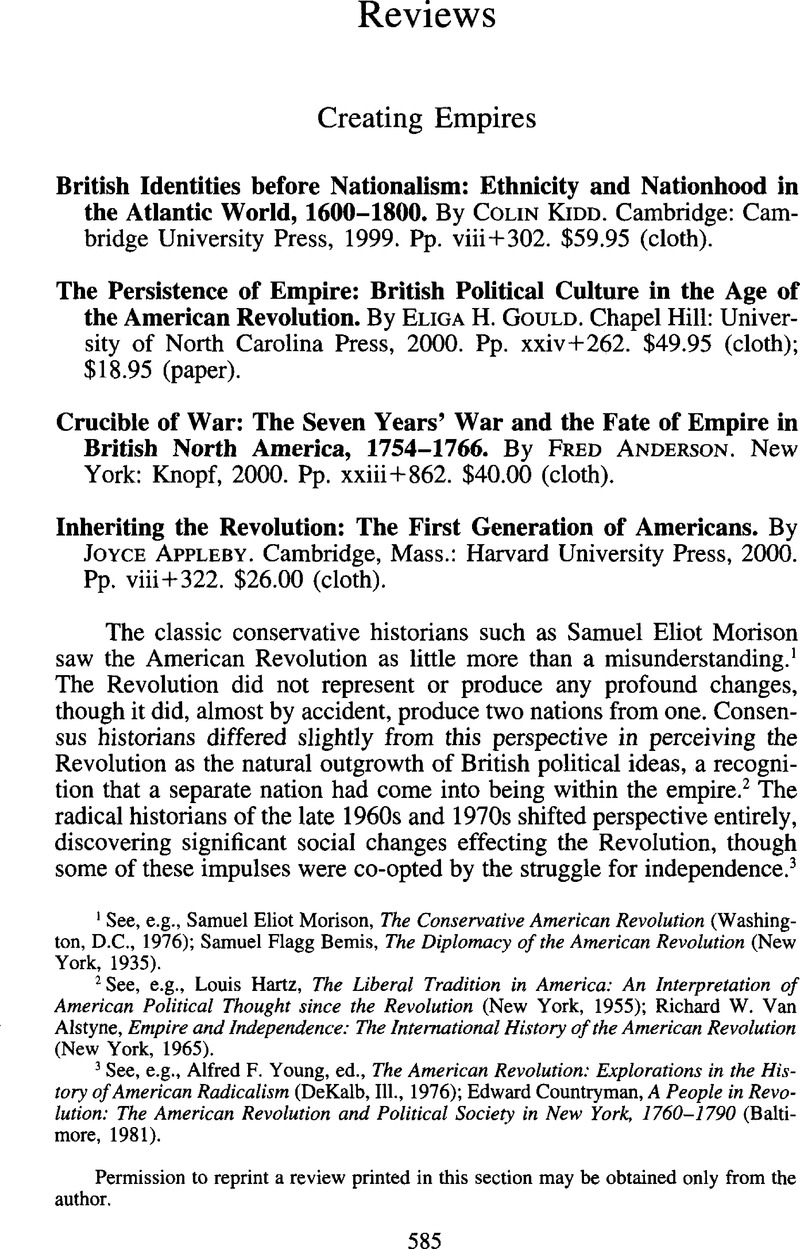

Creating Empires - British Identities before Nationalism: Ethnicity and Nationhood in the Atlantic World, 1600–1800. By Colin Kidd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Pp. viii + 302. $59.95 (cloth). - The Persistence of Empire: British Political Culture in the Age of the American Revolution. By Eliga H. Gould. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Pp. xxiv + 262. $49.95 (cloth); $18.95 (paper). - Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. By Fred Anderson. New York: Knopf, 2000. Pp. xxiii + 862. $40.00 (cloth). - Inheriting the Revolution: The First Generation of Americans. By Joyce Appleby. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000. Pp. viii + 322. $26.00 (cloth).

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 January 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Journal of British Studies , Volume 40 , Issue 4: At Home in the Empire , October 2001 , pp. 585 - 605

- Copyright

- Copyright © North American Conference of British Studies 2001

References

1 See, e.g., Morison, Samuel Eliot, The Conservative American Revolution (Washington, D.C., 1976)Google Scholar; Bemis, Samuel Flagg, The Diplomacy of the American Revolution (New York, 1935)Google Scholar.

2 See, e.g., Hartz, Louis, The Liberal Tradition in America: An Interpretation of American Political Thought since the Revolution (New York, 1955)Google Scholar; Van Alstyne, Richard W., Empire and Independence: The International History of the American Revolution (New York, 1965)Google Scholar.

3 See, e.g., Young, Alfred F., ed., The American Revolution: Explorations in the History of American Radicalism (DeKalb, Ill., 1976)Google Scholar; Countryman, Edward, A People in Revolution: The American Revolution and Political Society in New York, 1760–1790 (Baltimore, 1981)Google Scholar.

4 See, e.g., Draper, Theodore, A Struggle for Power: The American Revolution (New York, 1996)Google Scholar; Greene, Jack P., Peripheries and Center: Constitutional Development in the Extended Polities of the British Empire and the United States, 1607–1788 (New York, 1990)Google Scholar.

5 Sainsbury, W. Noelet al., eds., Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and the West Indies, 44 vols. (London, 1860–1969), 18:3Google Scholar.

6 Onuf, Peter S., Jefferson's Empire: The Language of Nationhood (Charlottesville, Va., 2000), p. 36Google Scholar.

7 Common Sense (1 August 1741), quoted in Langford, Paul, A Polite and Commercial People: England, 1727–1783 (Oxford, 1989), p. 172Google Scholar.

8 Quoted in ibid., p. 320.

9 Ibid., pp. 328–29.

10 Mossner, E. C., The Life of David Hume (Austin, Tex., 1954), pp. 405–6Google Scholar.

11 Langford, , A Polite and Commercial People, p. 328Google Scholar.

12 Cannon, J., ed., The Letters of Junius (Oxford, 1978), p. 161Google Scholar.

13 See particularly two recent collections from Cambridge University Press: Bradshaw, Brendan and Roberts, Peter, eds., British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707 (1998)Google Scholar; and Claydon, Tony and McBride, Ian, eds., Protestantism and National Identity: Britain and Ireland, c. 1650–c. 1850 (1998)Google Scholar.

14 Bailyn, Bernard, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), p. 26Google Scholar.

15 Mackesy, Piers, The War for America, 1775–1783 (Cambridge, Mass., 1964)Google Scholar; Atwood, Rodney, The Hessians: Mercenaries from Hessen-Kassel in the American Revolution (Cambridge, 1980)Google Scholar; Stephens, Thomas Ryan, “‘In Deepest Submission’: The Hessian Mercenary Troops in the American Revolution” (Ph.D. diss., Texas A&M University, 1998)Google Scholar.

16 Article 7 of the Bill of Rights of 1689 states that “the Subjects, which are Protestants, may have Arms for their Defence suitable to their Conditions and as allowed by Law.” Most readers, including Sir William Blackstone, perceive three qualifications to this “right”: it is limited by religious belief, social condition, and the law.

17 Both of the traditional names for the war are inaccurate: the Seven Years' War lasted nine years, and the French and Indian War involved many more parties.

18 Labaree, Leonard W.et al., eds., The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven, Conn., 1964), pp. 93–106Google Scholar; Flower, Milton Embick, John Dickinson, Conservative Revolutionary (Charlottesville, Va., 1983), pp. 11–19Google Scholar.

19 Quoted in Gould, , The Persistence of Empire, p. 59Google Scholar.

20 Tucker, Josiah, Treatise Concerning Civil Government (London, 1781)Google Scholar; Smith, Adam, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 2 vols. (London, 1776; reprint, 1922), 2:58–160, esp. pp. 89–108Google Scholar.

21 Onuf, , Jefferson's Empire, p. 7Google Scholar.

22 Boyd, Julian P.et al., eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 27 vols. (Princteon, N.J., 1950–1997), 1:129Google Scholar.

23 Mackesy, The War for America; Draper, A Struggle for Power; Dickinson, H. T., ed., Britain and the American Revolution (London, 1998)Google Scholar; Reich, Jerome R., British Friends of the American Revolution (Armonk, N.Y., 1998)Google Scholar.

24 Price, Richard, Observations on the Importance of the American Revolution (London, 1785), p. 6Google Scholar.

25 Langford, , A Polite and Commercial People, p. 620Google Scholar.

26 Ibid., p. 619.

27 Lipscomb, Andrew A., ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 20 (Washington, D.C., 1904–1905), 3:377–78Google Scholar.

28 Quoted in Onuf, , Jefferson's Empire, p. 57Google Scholar.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid., p. 186.

31 Kulikoff, Allan, The Agrarian Origins of American Capitalism (Charlottesville, Va., 1992), p. 242Google Scholar.

32 See Lease, Benjamin and Lang, Hans-Joachim, The Genius of John Neal: Selections from His Writings (Frankfurt am Main, 1978)Google Scholar.

33 Smith, Page, As a City upon a Hill: The Town in American History (New York, 1971), pp. 84–109Google Scholar.

34 On this general point, see Bellesiles, Michael A., Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture (New York, 2000), pp. 305–22Google Scholar.

35 Cress, Lawrence Delbert, Citizens in Arms: The Army and the Militia in American Society to the War of 1812 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1982)Google Scholar; Tucker, Robert W. and Hendrickson, David C., Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson (New York, 1990)Google Scholar.

36 See, e.g., Jefferson to Madison, 12 February 1799, in Lipscomb, , ed., Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 10:110–13Google Scholar.

37 Heyrman, Christine Leigh, Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt (New York, 1997)Google Scholar.

38 For a contrary view, see Genovese, Eugene D., A Consuming Fire: The Fall of the Confederacy in the Mind of the White Christian South (Athens, Ga., 1998)Google Scholar.

39 Grimsted, David, American Mobbing, 1828–1861: Toward Civil War (New York, 1998)Google Scholar.

40 Quoted in Onuf, , Jefferson's Empire, p. 9Google Scholar.

41 Boyd, et al., eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 7:540Google Scholar.

42 Appleby, , Inheriting the Revolution, p. 242Google Scholar.

43 de Tocqueville, Alexis, Democracy in America, trans. Lawrence, George (New York, 1969), pp. 254–55Google Scholar.

44 Boyd, et al., eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 20:97Google Scholar.