Article contents

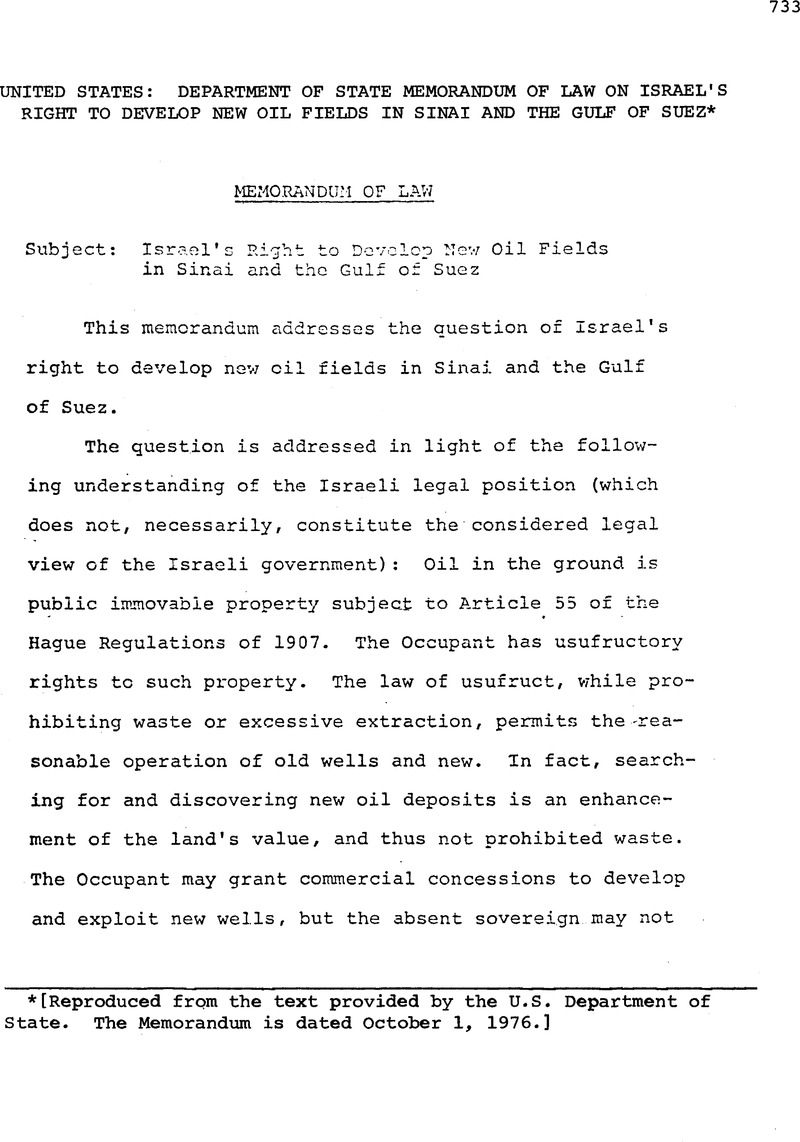

United States: Department of State Memorandum of Law on Israel's Right to Develop New Oil Fields in Sinai and the Gulf of Suez*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Other Documents

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1977

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of State. The Memorandum is dated October 1, 1976.]

References

1 See, E.H. Feilchenfeld, The International EconomicLaw of Occupation (1942) p. 817: “The textbooks areagreed that an occupant is not a sovereign.” Feilchenfeldcites, C.C. Hyde, International Law, Chiefly as Interpreted and Applied by the United Statin, (1922) p. 362; Oppenheim 5th” Edition, p. 345T F. von Liszt, Das Voelkerrecht systematise dargestellt, (1898), p. 228; and P./Fauchille, Traite de droit international public, (1921), Tome II, Guerre et Neutralite, p. 215. As Fauchille puts it, [f]or as long as the war lasts, the invader is not juridically substituted for the legal government. He is not the sovereign of the territory.His powers are limited to the necessities of the war“(Fauchille, p. 218, informally translated).. See also,Oppenheim's International Law, Lauterpacht ed., 7th Edition, Vol. II, pp. 432-434, hereafter cited asOppenheim.

2 See e.g., Judgement of the International MilitaryTribunal, Nuernberg, 1 Trial of the Major War Criminals253-54 (1947); U.S. v. Von Leeb, 11 Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 1, at 533; Oppenheim, (7th), Vol. II, pp. 234-35 and 397-415; Property in occupied territories must be disposed of “according to the strict rules laid down in the Hague Regulations” U.S. v. Krupp, 9 Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Tribunals 1341; The taking of property “must. be judged by reference exclusively to the Hague Regulations”, E. Lauterpacht, The Hague Regulations and the Seizure of Munitions de Guerre, 32 Brit. Y.B. Int’l. L. 218, 220 (1955).

3 C.P. Sherman, Roman Lav; in the Modern World, (1937)p. 142; E.R. Cummings, “Oil Resources in Occupied ArabTerritories Under the Law of Belligerent Occupation”, 9 The Journal of Int’l Law and Econ. 533, 557-558.

4 S. Siksek, The Legal Framework for Oil Concessionsin the Arab World, 9, 11 (1960).

5 Oppenheim, p. 397; Department of the Army Field Manual,The Law of Land Warfare, FM 27-10, p. 151; Cummings,pp. 558-559.

6 Department of the Army, International Law, (1962) Vol. II, p. 183.

7 Some civil code jurisdictions have not adopted even this permissive a rule and prohibit exploitation by a usufructuary of already operating mines, unless expressly authorized by the deed creating the usufruct. See, for example, Mexico, Article 1001; Puerto Rico, Article 1516; and Spain, Article 476. Spain, however, provides a limited exception, in Article 477, for operating existing mines on a profit-sharing basis with the owner.

8 The French Civil Code, Article 598, for example, provides: “He also has the use, in the same manner as the owner, of mines and quarries which are being exploited at the beginning of the usufruct; and, nevertheless, if the exploitation is one which requires a concession, the usufructuary can only enjoy it after having obtained the permission of the King (President of the Republic). “He has no right to unopened mines and quarries nor to peat-bogs which have not begun to be exploited nor to treasure which might be discovered during the period of the usufruct.” (Informal translation.) A partial survey shows similar express provisions are found in the civil codes of Argentina, Article 2900; Belgium, Article 598; Italy, Article 987; Louisiana, Article 552; and the Netherlands, Article 823. See also, G. Pugliese, “On Roman Usufruct”, 40 Tulane L. Rev. 523, 546-47; Sherman, C.P., Roman Law in the Modern World, (1937).p. 165.

9 E. Kuntz, A Treatise on the Law of Oil and Gas,p. 168 (1962). Blackstone, Commentaries on the Lawsof England, Book 2, Ch. 18.

10 See footnote 7 above.

11 Fauchille, pp. 253-5 4; Gerhard von Glahn, The Occupation of Enemy Territory, (1957), p. 177.

12 Stone, Julius, Legal Controls of InternationalConflict, (1959), p. 714.

13 Writing during World War II, Feilchenfeld stated:“[T]he Hague Regulations speak of ‘seizure’ [of publicchattels] not of ‘appropriation’. It would seem therefore,that no unlimited title is acquired.... It seemsadmitted that the occupant may sell, spend, otherwisedispose of seized public chattels during the occupation;but it is at least not beyond doubt that seized foodstores, for instance, may be sold abroad in order toenrich the home treasury of the occupant. The Frenchword saisie does not necessarily connote unlimited rights.”Feilchenfeld, pp. 53-54; A later writer stated that “[s]omejurxsts go 'so far as to justify the sale of [lawfully seized enemy movable public property], but the present writer believes that such a sale would violate the important restriction imposed by Article 53 of the Haque Requlations. That is, that the property in question must be usable for military purposes. If seized enemy property is not to be utilized by an occupant at a given time, hisauthorities should appoint property custodians who should be placed in control of the property in question” von Glahn, p. 183; “The Occupant may take possession of [the property of the occupied State under Article 53], provided that it may be used for operations of war. This is a power of requisition which the Occupant enjoys in relationto private property under Article 52. It is wider principally because the Occupant is not limited by the restriction that property should be required only for the necessities of the army of occupation. It is narrower for the reason that the Occupant does not acquire title by his act of seizure, but only obtains a right to use the property (if necessary to the point of consumption or destruction)” E. Lauterpacht, p. 221.

14 A sweeping statement on this point was contained in a resolution adopted by the London International Law Conference of 1943: “The rights of the occupant do not include any right to dispose of property, rights or interests for purposes other than the maintenance of publicorder and safety in the occupied territory. In particular,the occupant is not, in international law, vested with any power to transfer a title which will be valid outside that territory to any property, rights or interests which he purports to acquire or create or dispose of; this applies whether such property, rights or interests are those of the State or of private persons or bodies.” (Entire resolution is set out in von Glahn, pp. 194-96). The judgment in the trial of the major German war criminals included the following: “Article 49 of theHague Convention provides that an occupying power may levy a contribution of money from the occupied territory to pay for the needs of the army of occupation, and for the administration of the territory in question. Article 52 of the Hague Convention provides that an occupying power may make requisitions in kind only for the needs of the army of occupation, and that these requisitions shall be in proportion to the resourcesof the country. These articles, together with Article 48... S3, 55 and 56...make it clear that under the rules of war, the economy of an occupied country can only be required to bear the expenses of the occupation, and these should not be greater than the economy of the country can reasonably be expected to bear.” Judgement, I Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal 239 (1947) . See also the decisions reached in the U.S. Nuernberg trials, In re Flick, In re Krupp and In re Krauch. This reasoning was followed by Whyatt, C.J., in the Singapore Oil Stocks Case, who noted that the Japanese exploitation of Sumatran oil fields was part of a Japanese plan to “secure the oil resources of the Netherlands Indies, not merely for the purpose of meeting the requirements of an army of occupation but for supplying the naval,military and civilian needs of Japan both at home andabroad, during the course of the war against the Allied Powers.” Citing the decisions of the International and United States Military Tribunals, Whyatt concluded that “the seizure and the subsequent exploitation by the Japanese armed forces of the oil resources of the appellants in Sumatra was in violation of the laws and customs of war and, consequently, did not operate to transfer the appellants' title to the belligerent occupant.” 51 Am. J. Int’l L. at 808 (1957).

15 Stone, p. 697.

16 E. Lauterpacht, p. 222.

17 von Glahn, p. 209.

18 see, Stone, p. 698.

19 von Glahn, p.

19a it has been asserted that the oil activities and rightsin the Gulf are those of GUPCO (the Gulf of Suez PetroleuiaCompany) and not those of Amoco. However, GUPCO is a nonprofit Egyptian corporation which carries out operations-under the concession agreement as the agent of Amoco andEGPC (Egyptian General Petroleum Company). The use of anagent does not affect the status of Amoco as a principalin the operations conducted and rights held under a concession.

20 This is the considered opinion of the State DepartmentGeographer. Egypt has taken none of the actions which would have been necessary to extend the territorial sea through baselines, or to close the Gulf and make its waters internal. While Egypt claims a twelve mile territorial sea, the United States continues to refuse recognition to any claims beyond three.

21 Even in a case of state succession, acquired rights of a concessionaire must be respected by a successor state.D.P. O’Connel, “Economic Concessions in the Law of State Succession”, 27 Brit. Y.B. Int’l L. 93, 116 (1951). A fortiori, they must be respected by a belligerent occupantwhose rights fall far short of a successor sovereign's.The United States appears to have considered propertyrights based on concessions to be protected, and the occupant bound to respect those rights, even prior to the Kague Regulations. See Cummings, n. 148, pp. 570-571, and the numerous authorities cited therein.

22 In the Lighthouse Case, the Permanent Court of International Justice considered as binding a concession contract for the usufruct of public immovable property granted in 1913 by the absent sovereign, Turkey, while the territory was under Greek belligerent occupation. The ad hoc judge appointed by the Greek Government argued that theoccupant has the exclusive right to grant a concession tothe usufruct of public immovable property. However, themajority did not acknowledge such a rule. The Court foundit could decide without ruling on the point. The concessionagreement, while concluded in 1913, covered the period1924-1949, long before which the occupant, Greece, hadbecome the sovereign. World Court Reports, Hudson, ed., Vol. Ill, pp. 368, 383, 388-89, 407-409.

23 Looking to pre-World War II authority, McNairstated: “It is at any rate arguable that, assumingthe new law to fall within the category of that large portion of national law which persists during the ..occupation and which the enemy occupant cannot lav/fullychange or annul, it ought to operate in occupied territoryin spite of the absence of power to make it effective during the occupation.” McNair, Legal Effects of War (1948) p. 383. The matter is somewhat differently stated in the leading American case: “In short, the legitimate sovereign should be entitled to legislate over occupied territory insofar as such enactments do not conflict with the legitimate rule of the occupying power.” State of Netherlands v. Federal Reserve Bank of New York et. al., 201 F.2d 455 at 462 (U.S.C.A.2nd Circuit 1953) . See this opinion for a thorough statement of the law and for citations to the relevant cases. “The currently accepted principle appears to be that the legitimate sovereign may legislate for an occupied portion of his territory, provided that his laws do not conflict with the powers of the occupant as outlined in conventional international law.” von Glahn, p. 35, Apparently, only the post-war decisions of Greek courts are contra.

- 5

- Cited by