Article contents

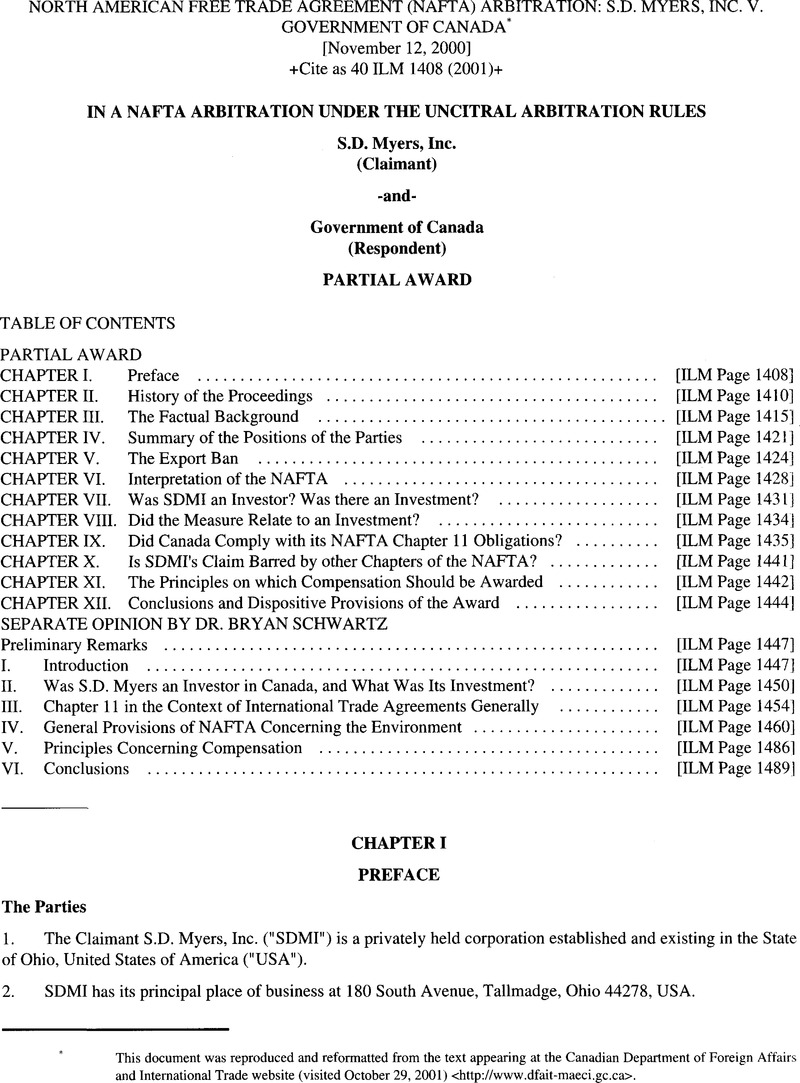

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Arbitration: S.D. Myers, Inc. v Government of Canada

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2001

References

End notes

* This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade website (visited October 29, 2001) <http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca>.

1 In the international context this is equivalent to state or cabinet privilege.

2 Transcript, February 15, 2000, p. 475.

3 Valentine affidavit, paras. 7-12.

4 Transcript, February 15, 2000, p. 475.

5 Ibid.

6 Mr. Jeff Smith, then employed as a political assistant to the Minister of the Environment, was asked if Canada would be willing to provide funds to SDMI for the purpose of constructing a treatment facility in Canada. The answer was “No.“v

7 There were exceptions for U.S. military PCB's and a few minor enforcement discretions.

8 Investor's Supplemental Memorial, paras. 78-79.

9 This is a direct reference to SDMI's Statement of Claim. A more accurate description of the obligation is the provision of the same in- jurisdiction treatment.

10 Joint Book of Documents, vol. 3, tab 86.

11 Lot. Cit, tab 80.

12 Op. Cit., vol. 4, tab 101.

13 Unless otherwise stated, references to “minister” and “ministries” are to those of the Federal Government.

14 Joint Book of Documents, vol. 2, tab 43.

15 Op. Cit., vols. 2 and 3, tabs 39 and 81.

16 This evidence is from the cross-examination of Mr. Mates on an affidavit filed in other proceedings.

17 Joint Book of Documents, vol. 3, tab 43.

18 Op. Cit., vol. 1, tab 17.

19 Op. Cit., vol. 2, tab 59.

20 Op. Cit., vol. 3, tab 86.

21 Op. Cit., vol. 2, tab 56.

22 Op. Cit., vol. 3, tab 80.

23 Op. Cit., vol. I,tab6.

24 Loc. Cit, tab 30.

25 Ibid.

26 Op. Cit, vol. 2,tab 58

27 Loc.Cit.,tab 35.

28 Loc.Cit.,tab 42.

29 Ibid

30 Op.Cit.,vol.l,tab 2.

31 Op.Cit.,vol.3,tab 84.

32 Op.Cit..vol.10.tab 1 Op. Cit., vol. 10, tab 186. In fact, it was a condition of the US EPA's permission to SDMI that imported PCB wastes should not be land filled. SDMI did not use landfill methods.

33 The Tribunal has noted that there were other equally effective means of encouraging the development and maintenance of a Canadian- based PCB's remediation industry.

34 The Tribunal does not suggest that national law is irrelevant, as it may be relevant in various ways; but the general principle of interpretation is clear.

35 Insofar as Canada did refer to its domestic legal regime, it anchored its position on the contention that the measure was necessary to protect health and the environment.

36 NAFTA's Commission for Environmental Cooperation issued a report in June 1996 on the Status of PCB Management in North America. Its discussion of the various agreements notes that “Although NAFTA is designed to promote free, uninhibited trade between the three countries, it also recognizes the supremacy of the Basel Convention, the 1986 Agreement between Canada and the U.S. and the 1983 La Paz Agreement between the United States and Mexico in case of any inconsistency between NAFTA and these environmental agreements. In fact, the Canada-U.S.-Mexico hazardous waste agreements are predicated upon the free movement of hazardous waste between the parties subject to prior notice and consent by the importing country. The Basel Convention principles that disposal facilities be established within the country generating waste and that transboundary movement of waste shall be reduced to the minimum do not apply to bilateral movements of hazardous waste between the U.S. and Mexico or Canada because these would be governed by the principle of the freedom of movement, subject to notification and consent of the country of import.” [Authorities, tab 41.]v

37 SDMTs Notice of Arbitration, Section C.

38 Ibid. Section E.

39 See generally the evidence of Dana Myers, Transcript, February 15, 2000.

40 Article 1139 refers incorporates the definition in Article 201 which says that…enterprise means any entity constituted or organized under applicable law . .

41 . Transcript, February 14, 2000, pp. 34, 117.

42 Transcript, February 15, 2000, pp. 139-152.

43 Article 1102(4) appears to be of little relevance to the current discussion. It confirms that a state cannot require that a minimum level of equity in an enterprise in its territory be held by its own nationals, and that an investor of another Party cannot be required to sell or otherwise dispose of its investment in the territory of the Party.

44 [1989] 1 S.C.R. 143, at paragraphs 27 to 31. Decisions of U.S. courts are to a similar effect. Although domestic law is not controllingin Chapter 11 disputes, it is not inappropriate to consider how the domestic laws of the parties to the dispute address an issue.

45 The USA on behalf ofGeorge W. Hopkins v. The United Mexican States (Docket No. 39), 21American Journal of International Law 160, at 166-167(1926).

46 F.A. Mann, “British Treaties for the Promotion and Protection of Investments” (1981) 52 Brit. Y.B. Int'l L. 241 at p. 243.

47 The fact that the border was closed again on the U.S. side in July 1997 cannot be laid at Canada's door.

48 This is a matter for argument at a later stage of the proceedings.

49 Award of June 26, 2000, para. 104.

50 Wt/396/R.

51 The Dispute Settling Panel, at footnote 422 to the quoted passage, elaboratesThe principle of interpretation against conflict has been confirmed by the Appellate Body in Canada —Certain Measures Concerning Periodicals adopted on 30 July 1997, WT/DS31/AB/R, (“Canada Periodicals“), page 19; in EC Bananas, paras. 219-222; in Guatemala Cement, para. 65; and by the panel in Indonesia — Certain Measures Affecting the Automobile Industry, adopted 23 July 1998, WT/DS54, 55, 59 and 64/R (not appealed) (“Indonesia Autos“), para. 14.28. For a definition of conflict, see for instance the Appellate Body statement in Guatemala Cement, para. 65 or the Panel Report on Indonesia Autos, para. 14.28.

52 According to some commentators, that express provision was intended to resolve a long standing difference of opinion between the USA and Mexico over compensation in expropriation cases. The latter contended that in the case of a lawful expropriation, a lower standard of compensation might be more appropriate than all of the economic loss sustained.

53 The Tribunal does not suggest that punitive damages may be awarded, as these are expressly prohibited by NAFTA

1 S.D. Myers argued that it qualified as having an investment in Canada under definition 1139(h): “Interests arising from the commitment of capital or other resources in the territory of a Party to economic activity in such territory, such as under:

-

(i)contracts involving the presence of an investor's property in the territory of the Party, including turnkey or construction contracts or concessions;

-

(ii) contracts where remuneration depends substantially on the production, revenue or profits of an enterprise.“ I would leave it to the next round for the parties to explore this argument in more detail if either thinks that doing so has some effect on the measure of compensation in this case. They may, if they wish, similarly explore S.D. Myers’ argument that it qualified under definition 1139(e), an interest in an enterprise that entitles the owner to share in income or profits of the enterprise.

2 Article 201 defines an “enterprise” as including “any entity constituted or organized under applicable law, whether or not for profit, and whether privately-owned or governmentally-owned, including any corporation, trust, partnership, sole proprietorship, joint venture or other association.“

3 Article 1139 of NAFTA defines “enterprise” as including “a branch of an enterprise.“

4 InManitoba Fisheries Ltd. v. Canada, [1979] 1 S.C.R. 101 a company had many loyal customers who used its services as a fish marketer. A federal statute then intervened and required that fish producers instead use the marketing services of a Crown corporation. The company was effectively put out of business. It claimed that an expropriation had taken place. The federal government, it claimed, had expropriated its goodwill. The Supreme Court of Canada agreed. I will refrain at this stage from deciding whether either “market share” or “goodwill” are included in the “property” branch of the definition of investment under Chapter 11 of NAFTA; see Article 1139(g). I will also refrain from exploring any similarities and differences between the facts of the Manitoba fisheries case and those before this tribunal in this case.

5 See generally Vandevelde, K. J., United States Investment Treaties: Policy and Practice(Deventer:Kluwer Law and Taxation, 1992)Google Scholar and Sornarajah, M.,The International Law on Foreign Investment,(New York:Cambridge University Press, 1994) at.225–276 Google Scholar.

6 Statement on Implementation, CanadaGazette Part 1 (1 January 1994) 68 at 148

7 The TRIMs Agreement applies only to “investment measures related to goods.” Parties are prohibited from adopting such measures that breach two core articles of the original GATT agreement, Articles III and Article XI. Article III (National Treatment) of GATT requires a state to extend “national treatment” — the most favorable treatment it applies to its own goods. In that way the good is regulated or taxed once it has entered the local stream of commerce. Article XI (Quantitative Restrictions) of GATT proscribes limitations on the import and export of goods.

8 See generally I. S. Moreno, J. W. Rubin, R. F. Smith III, and T. Yang, “Free Trade and the Environment: the NAFTA, the NAAEC and Implications for the Future” (1999) 12 Tulane International Law Journal 405 at 458-459. The authors summarize a recent report of the WTO's Committee on Trade and the Environment as follows:

The CTE Report concluded, however, that the WTO was interested in building a constructive relationship between trade and environmental concerns. It stated that trade and the environment were both important areas of policy-making and should be mutually supportive to promote sustainable development. The Report further indicated that governments had the right to establish their national environmental standards in accordance with their own conditions, needs and priorities, but that it was inappropriate for them to relax their existing standards or enforcement merely to promote trade. The Report acknowledged that an open, equitable and non-discriminatory multilateral trading system and environmental protection are essential to promoting sustainable development. Finally, the CTE Report noted that removal of trade restrictions and distortions, in particular high tariffs, tariff escalation, export restrictions, subsidies, and non-tariff barriers, can potentially yield benefits for both the multilateral trading system and the environment.

9 Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Canada concerning the Trans boundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes C.T.S. 1986 No. 39 (Date of Entry into Force 11 August 1986).

10 For more information on the Basel Agreement, see K. KummerInternational Management of Hazardous Wastes: The Basel Convention and Related Legal Rules (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

11 NAFTA's own Commission for Environmental Cooperation issued a report in June 1996 on the Status of PCB Management in North America. Its discussion of the various agreements notes that:

Although NAFTA is designed to promote free uninhibited trade between the three countries, it also recognizes the supremacy of the Basel Convention, the 1986 Agreement between Canada and the United States, and the 1983 La Paz Agreement between the United States and Mexico in case of any inconsistency between NAFTA and these environmental agreements. [Actually, Basel is not supreme unless and until ratified]. In fact, the Canada — U.S. and Mexico — U.S. hazardous waste agreements are predicated upon the free movement of hazardous waste between the parties subject to prior notice and consent by the importing country. The Basel Convention principle that disposal facilities be established within the country generating waste and that trans boundary movement of waste shall be reduced to the minimum do not apply to bilateral movements of hazardous waste between the United States and Mexico or Canada because these would be governed by the principle of freedom of movement, subject to notification and consent of the country of import.Joint Book of Documents, Volume I, Tab 4.

12 NAAEC, Article 10(3)(b).

13 Article 1102(4) appears to be of little relevance to the current discussion. It clarifies that a state cannot require that a minimum level of equity in an enterprise in its territory be held by its own nationals, and that an investor of another Party cannot be required to sell or otherwise dispose of its investment in the territory of the Party.

14 [1989] 1 S.C.R. 143, at paragraphs 27 to 31.

15 AB-1996-2

16 OECD International Investment and Multinational Enterprises: National Treatment of Foreign-Controlled Enterprises (Paris: OECD, 1985) at 17.

17 The Treasury Board policy does not, by itself, render a regulation passed in an inconsistent manner illegal under the laws of Canada.

18 Joint Book of Documents, Volume III, Tab 78.

19 EC — Bananas, AB-1997-3; WT/DS27/AB/R, 9 September 1997at paragraph 221;Memorial of the Investor, 25 at paragraph 35.

20 WT/DS54/R, WT/DS55R, WT/DS59R, WT/DS64/R, (2 July 1998), at paragraphs 14.52-53;Memorial of the Investor, 26 paragraph 36.

21 The Dispute Settling Panel, at footnote 422 to the quoted passage, elaborates:

The principle of interpretation against conflict has been confirmed by the Appellate Body in Canada— Certain Measures Concerning Periodicalsadopted on 30 July 1997, WT/DS31/AB/R, (“Canada Periodicals”),page 19; in EC— Bananas,paras. 219-222; in Guatemala— Cement,para.65; and by the panel in Indonesia— Certain Measures Affecting the Automobile Industry,adopted 23 July 1998, WT/DS54, 55, 59 and 64/R (not appealed) (“Indonesia— Autos”),para. 14.28. For a definition of conflict, see for instance the Appellate Body statement in Guatemala— Cement,para. 65 or the Panel Report on Indonesia— Autos,para. 14.28.

22 Joint Book of Documents, Volume I, Tab 17.

23 See, for example, Martin Wagner, J., “International Investment, Expropriation and Environmental Protection” (1999) 29 Golden Gate University Law Review 465.Google Scholar

24 Pennsylvania Coal Co. v.Mahon, (1922) 260 U.S. 393, at 415. For an overview of more recent pronouncements from the Supreme Court of the United States,see D.L. Callies editor,Takings: Land-Development Conditions and Regulatory Takings After Do/an and Lucas (American Bar Association 1996). There is a useful review of expropriation laws in the three NAFTA countries in Wagner,ibid. In addition,see generally Mouri, A. The International Law of Expropriation as Reflected in the Work of the Iran-US. Claims Tribunal (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 1994)Google Scholar.

25 “The United States of America on behalf of George W. Hopkins, Claimant, v. the United Mexican States (Docket No. 39)” (1926) 21American Journal of International Law 160 at 166-167.

26 Mann, F. A., “British Treaties for the promotion and protection of Investments” (1981) 52 Brit. Y. B. Int'l L. 241 at 243Google Scholar.

27 United States — Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products WT/DS58/AB/R (12 October 1998) 55 at paragraph 183.

28 Cheng, B., General Principles of Law as applied by International Courts and Tribunals (London: Stevens ' Sons Ltd., 1953)Google Scholar at 122:Memorial of the Investor, 50 at paragraph 114.

29 See NAFTA, Article 1108(7).

30 Germany v.Poland (1922) 17 P.C.I.J. Ser. A No. 17, 3 at 47;Memorial of the Investor, 78 at paragraph 212.

- 12

- Cited by