Article contents

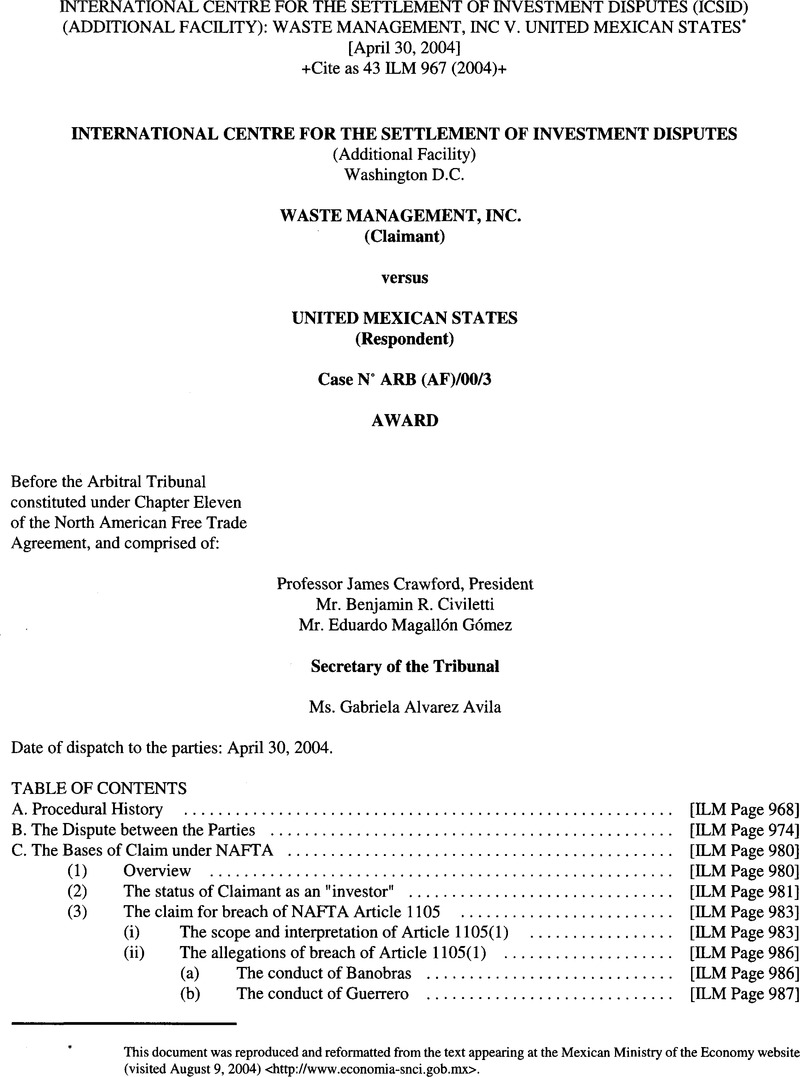

International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) (Additional Facility): Waste Management, Inc v. United Mexican States

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2004

References

* This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the Mexican Ministry of the Economy website (visited August 9, 2004)<;http://www.economia-snci.gob.mx.>

1 For the Award of 2 June 2000 see 5 ICSID Reports 443.

2 Inter-American Convention on International Commercial Arbitration, Panama City, 30 January 1975, 1438 UNTS 249.

3 The Tribunal's Decision is reported at 6 ICSID Reports 541.

4 The Tribunal's Decision is reported at 6 ICSID Reports 541.

5 Setasa negotiated with Acaverde's principal shareholder, Sanifill, for the purchase of Acaverde in 1997 and accordingly received confidential information about the company as part of the due diligence process. It is this information which was the subject of the Respondent's letter to the Tribunal of 12 November 2002. See further para. 66.

6 USA Waste Services Inc. merged with Acaverde's principal shareholder, Sanifill, in 1996. The merged company was subsequently renamed Waste Management, Inc.

7 The relationship between Acaverde and its parent companies is discussed at paras. 77-85, below.

8 “NP” refers to Mexican New Pesos.

9 Translation by the Tribunal. The original reads: “En caso que una o más disposiciones hechas contra la línea no se paguen en el plazo de 90 días, el Banco procederá sin demora a hacer efectiva la garantía correspondiente al las participaciones presentes y futuras que le correspondan en ingresos federales al Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero, recuperando así las cantidades pagadas a ‘Acaverde, S.A. de C.V.', con cargo a este crédito.“

10 Mr. Rodney Proto, transcript, 7 April 2003, 102; Mr. Steven Walton, ibid., 282-7. Acaverde's Mexican lawyer, Mr. Jaime Herrera stated that Acaverde did not participate in the drafting of the Line of Credit Agreement and that its suggestions in that regard were rejected by Banobras (Herrera Statement, para. 9; see also Banobras’ letter to Sanifill of 19 June 1995). But it is clear that Acaverde, which had agreed to the amended Concession Agreement at Banobras’ insistence, had notice of the precise terms of the Line of Credit Agreement when it commenced operations in August 1995: ibid., para. 8.

11 In the correspondence preceding the Line of Credit Agreement, its limitations are consistently spelled out: e.g. in the letter of the State Delegate, Banobras to Acaverde, 26 May 1995. Subsequently (but before operations commenced), Banobras made it clear that the terms of the Agreement could not be changed: State Delegate, Banobras to Acaverde, 19 June 1995.

12 Decree No. 127, 15 December 1994, published in the Guerrero Official Gazette, 3 January 1995.

13 See e.g., Mr. Rodney Proto, transcript, 7 April 2003, 89, lines 7-11.

14 E.g., letters of Acaverde to the City, 2 September 1996, 13 December 1996.

15 See Statement by Mr. D. Harich, a civil engineer employed by Waste Management to design the proposed landfill.

16 “No es obligatorio Acaverde: ROA”, El Sol de Acapulco, 13 October 1995, p. 1.

17 The City made a swap proposal in respect of the 1995 invoices which Acaverde refused, as it was entitled to do.

18 Witness statement of Mr. Rogelio Moreno Jarquin, 4 December 2002, para. 8 (emphasis added).

19 In accordance with a request of the City to Setasa, 12 November 1997.

20 See further Compania deAguas delAconquija S.A. & Vivendi Universal v. Argentine Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/97/3), Decision on Annulment, (2002) 6 ICSID Reports 340, 365-7 (paras. 95-101), cited with approval by the Tribunal in SGS Societe Generate de Surveillance S.A. v. Islamic Republic of Pakistan, (ICSID Case No. ARB/01/13), decision of 6 August 2003, (2003) 18 ICSID Rev.-FILJ 307,352-6 (paras. 147-8). See also Azinian, Davitian & Baca v. United Mexican States (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/97/2), (1998) 5 ICSID Reports 269, 286 (paras. 81, 83).

21 Statement of Mr. Mario Alcaraz Alarcón, para. 3.

22 Annexed to GA Res. 56/83, 12 December 2001.

23 The ILC's commentary describes the notion of a “para-statal” entity as a narrow category: the essential requirement is that the entity must be “empowered by the law of the State to exercise functions of a public character normally exercised by State organs, and the conduct of the entity [which is the subject of the complaint] relates to the exercise of the governmental authority concerned”: Commentary to Article 5, paras. 2 and 7, reproduced in Crawford, J, The International Law Commission's Articles on State Responsibility (Cambridge, 2002) 100, 102.Google Scholar

24 ILC Articles, Art. 8; see the commentary, esp. para. 6, in Crawford, 112-113.

25 See below, paras. 103, 139 for the Tribunal's findings on this point.

26 Mr. Walton, transcript, 7 April 2003, 233.

27 Novedades (Acapulco), 30 October 1994, identifying Sanifill Inc. as the prospective concessionaire.

28 On 30 November 1995, a merger agreement left Sanifill de Mexico, S.A. de C.V., a Mexican company, as the sole successor of the various intermediate holding companies of Aceverde, the ultimate controlling interest of which was in Sanifill.

29 NAFTA, Article 1113(2).

30 Memorial, para. 5.43.

31 Reply, paras. 4.32-4.33.

32 Reply, paras. 4.32, 4.39-4.40.

33 Mondev International Limited v. United States of America, Award of 11 October 2002, 6 ICSID Reports 192.

34 ADF Group Inc. v. United States of America, Award of 9 January 2003, 6 ICSID Reports 470.

35 Mondev International Limited v. United States of America, Award of 11 October 2002, 6 ICSID Reports 192, 216 (para. 98), 223 (para. 120). See also ADF, 527 (para. 178).

36 Mondev International Limited v. United States of America, 216 (para. 98).

37 Ibid., 223 (para. 121).

38 Ibid., 223 (para. 122).

39 Ibid., 224 (para. 125).

40 ADF Group Inc. v. United States of America, Award of 9 January 2003, 6 ICSID Reports 470, 527-8 (para. 179).

41 USA(L.F.Neer)v. United Mexican States, 1927, AJIL 555, at 556, cited in Mondev, 221 (para. 114).

42 S.D. Myers, Inc. v. Government of Canada, Partial Award, 13 November 2000, para. 263. The majority (Arbitrator Chiasson dissenting) considered that the facts which supported a finding of breach of Article 1102 also established a breach of Article 1105, para. 266.

43 Mondev v. United States, 225-6 (para. 127).

44 Ibid., 528-31 (paras. 180, 183-4).

45 Ibid., 531 (para. 184).

46 Ibid., 531 (para. 188).

47 Ibid., 531-2 (para. 189).

48 Ibid., 532-3 (para. 190).

49 Ibid., 533 (para. 191).

50 The Loewen Group, Inc. and Raymond L. Loewen v. United States of America, Award of 26 June 2003 (Case No. ARB(AF)/98/3). For the Tribunal's discussion of the Article 1105 and the FTC interpretation see ibid., paras. 124- 8.

51 Ibid., para. 132.

52 Ibid., para. 135.

53 Ibid., para. 168.

54 Ibid., para. 137.

55 See Lovett, William A., “Lessons from the Recent Peso Crisis in Mexico”, (1996) 4 Tulane JICL 143.Google Scholar

56 The monthly fee increased from NP1 million to NP1.6 million in January 1996.

57 See e.g., Claimant's Memorial, para. 1.1.

58 Statement of Mr. Mario Alcaraz Alarcón, para. 4.

59 Ibid., para. 7.

60 See e.g. the letter from the State Representative, Mr. Alcaraz Alarcon to his superior in the Banobras head office, 10 October 1996.

61 Second Statement of Mr. Alcaraz Alarcón, paras. 4-5.

62 The land in question was ejido land (a form of customary or communal title). The agreement of 5 August 1995 conferred rights of exclusive use of 56 hectares of land for 25 years for use as a sanitary landfill by Acaverde.

63 See Mayor Almazán's letter to Banobras, 26 August 1996 and the reply of 4 September 1996.

64 E.g., letter of Mr. Proto to the Secretary-General of the City, 24 April 1996.

65 Statement of Mr. D. Harich, paras. 4, 10.

66 Maffezini v. Spain, Award, 13 November 2000, 5 ICSID Reports 419, 432 (para. 64), cited in para. 29 of CMS Gas Transmission Company v. Argentina, Decision of the Tribunal on Objections to Jurisdiction, 17 July 2003, 42ILM 788 (2003). See also Eudoro A. Olguín v. Republic of Paraguay, ICSID Case No. ARB/98/5, Award, 26 July 2001, 6 ICSID Reports 164, paras. 72-75.

67 See below, paras. 155-176.

68 For the terms of Article 17 of the Concession Agreement see para. 53 above.

69 Cf.Azinian, Davitian &Baca v. United Mexican States, Award of 1 November 1999, 5 ICSID Reports 269, 289 (para. 97).

70 The Claimant asserts that Canaco imposed the requirement for deposit of costs “because it was concerned about its own liability in the nullification lawsuit if the arbitration continued”. Whether or not its concerns were justified, they were still those of Canaco as a private entity, and there is no sufficient evidence that the judicial process was dilatory or gave unfair advantages to state entities in seeking to avoid domestic arbitration clauses to which they had agreed.

71 Order of Permanent Arbitration Commission, National Chamber of Commerce of Mexico City, 18 June 1998.

72 H. Juzgado Primero de Distrito en Materia Civil en el Distrito Federal. Juicio Ordinario Mercantil, expediente 12/97, Acaverde, S. A. de C. V. v. Banco Nacional de Obral y Servicios Públicos, Sociedad Nacional de Crédito.

73 Decision of the First Civil District Court of the Federal District, 7 January 1999.

74 H. Segundo Tribunal Unitario del Primer Circuito. Toca Civil 16/99-11.

75 Decision of 11 March 1999.

76 H. Sexto Tribunal Colegiado en Materia Civil del Primer Circuito. Amparo Directo D. C. 5026/99.

77 Decision of 6 October 1999.

78 H. Juzgado Segundo de Distrito en Materia Civil en el Distrito Federal. Juicio Ordinario Mercantil, expediente 88/98. Acaverde, S. A. de C. V. v. Banco Nacional de Obras y Servicios Públicos, Sociedad Nacional de Crédito. Institucion de Banca de Desarrollo.

79 Decision of 12 January 1999.

80 H. Primer Tribunal Unitario del Primer Circuito. Toca Civil 24/99-1.

81 Interlocutory Decision, 18 February 1999.

82 H. S é ptimo Tribunal Colegiado en Materia Civil del Primer Circuito. Amparo Directo D. C. 2870/99.

83 See above, para. 51.

84 In Azinian the tribunal also addressed whether the Claimants could have successfully pursued a denial of justice claim. It said: “A denial of justice could be pleaded if the relevant courts refuse to entertain a suit, if they subject it to undue delay, or if they administer justice in a seriously inadequate way.... There is a fourth type of denial of justice, namely the clear and malicious misapplication of the law [which] ... overlaps with the notion of 'pretence of form' to mask a violation of international law.” However, in the view of the tribunal, the findings of the Mexican courts could not “possibly be said” to be in any way a denial of justice, Azinian, Davitian & Baca v. United Mexican States, Award of 1 November 1999, 5 ICSID Reports 269, 290 (paras. 102-103).

85 Mondev International Limited v. United States of America, Award of 11 October 2002, 6 ICSID Reports 192.

86 The ADF Tribunal, rejecting the investor's submission that a federal administrative body had acted ultra vires in its interpretation of the measures in question, the Tribunal said, ”…even had the investor made out a prima facie basis for its claim, the Tribunal has no authority to review the legal validity and standing of the US measures… under US internal administrative law. We do not sit as a court with appellate jurisdiction…. The Tribunal would emphasize, too, that even if the US measures were somehow shown or admitted to be ultra vires under the internal law of the United States, that by itself does not necessarily render the measures grossly unfair or inequitable under the customary international law standard of treatment embodied in Article 1105(1) … [S]omething more than simple illegality or lack of authority under the domestic law of a State is necessary to render and act or measure inconsistent with the customary international law requirements of Article 1105(1)…”, ADF Group Inc. v. United States of America, Award of 9 January 2003, (para. 190).Nor was the authority's refusal to follow prior rulings “grossly unfair or unreasonable” on the facts presented by the investor.

87 The Loewen Group, Inc. and Raymond L. Loewen v. United States of America, Award of 26 June 2003, (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/98/3). For the Tribunal's discussion of Article 1105 and the FTC interpretation see ibid., paras. 124- 128.

88 Ibid., paras. 119-123.

89 Loewen, para. 123.

90 See Claimant's Memorial, paras. 3.74-3.76.

91 A 60 day letter of intent was concluded between Sanifill & Setasa on 27 February 1997: see above, para. 66.

92 See Statement of J. Herrera, para. 21.

93 Case Concerning Elettronica Sicula S.P.A. (ELS1) (United States of America v. Italy), 1989 ICJ Reports 15.

94 See e.g., Claimant's Memorial, para. 3.65.

95 Statement of Mr. Mario Alcaraz Alarcon, para. 22 (“Nobody at Banobras had anything to do with the sending of this letter.“); Second Declaration of Mr. Mario Alcarez Alarcon, paras. 7-8 (“I deny that there was any type of coordination of the actions taken by the City Council and those taken by the Bank… Neither I nor the personnel of the Banobras office for which I was responsible took part in any discussion of [the cancellation of the concession].“).

96 Reply, para. 4.23.

97 Liberian Eastern Timber Corporation [LETCO] v. Government of the Republic of Liberia (1986) 2 ICSID Reports 343.

98 Ibid., 359.

99 Ibid., 363.

100 Ibid., 366-7.

101 Arbitral Award, 15 March 1963, 35 ILR 136 (1967). The decision was later set aside by an Iranian court: see 9 ILM 1118 (1970).

102 35 ILR 136, 185.

103 Memorial, para. 5.30.

104 35 ILR 136, 170-6. Arbitrator Calvin found that the law of the contract was the rules of law “common to civilized nations” on the basis that the parties had not specified the applicable law in the contract, and the contract was fundamentally different from the ordinary commercial contract envisaged by the rules of private international law because of its long-term and quasi-international character.

105 The term “expropriation” was not used by the arbitrator in Sapphire.

106 Interim Award of 26 June 2000, 122 ILR 293, 334-337.

107 S.D. Myers, Inc. v. Government of Canada, Partial Award, 13 November 2000, para. 283, cited in Claimant's Reply, fn 184: see <http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/tna-nac/disp/SDM_archive-en.asp.> This was an arbitration conducted under the UNCITRAL Rules.

108 Ibid., paras. 280-1.

109 Ibid., para. 285.

110 Ibid., paras. 285-6, citing Pope & Talbot, Inc. v. Canada, Interim Award, 26 June 2000, para. 104.

111 S.D. Myers, para. 286.

112 Ibid., para. 287.

113 Metalclad Corporation v. United Mexican States, Award, 30 August 2000, 5 ICSID Reports 209.

114 Ibid., 230 (para. 103).

115 The tribunal found that under federal law the municipal authority had the power to issue or refuse construction permits on construction grounds only, and its denial of the permit on ecological grounds was ultra vires: ibid., 228 and 230 (paras. 92, 106).

116 Ibid., 230 (paras. 106-7)

117 Ibid., 231 (paras. 109, 111).

118 United Mexican States v. Metalclad Corporation, decision of 2 May 2001, 2001 BCSC 664, 5 ICSID Reports 236.

119 Ibid., 5 ICSID Reports 236, 253 (para. 66).

120 Ibid., 255 (paras. 78-9).

121 Ibid., 259-60 (paras. 100, 105).

122 Ibid., 259 (para. 99)

123 Mr. Rodney Proto, transcript, 7 April 2003, 194.

124 Memorial, para. 5.8; Reply, para. 4.23.

125 See paragraphs 153-154 above.

126 See paragraph 56 above for the statement and its context.

127 Mondev International Limited v. United States of America, Award of 11 October 2002, 6 ICSID Reports 192, 216 (para. 98).

128 Azinian, Davitian x0026; Baca v. United Mexican States, Award of 1 November 1998, 5 ICSID Reports 269.

129 Ibid., 288 (para. 89).

130 Ibid., 288 (para. 90).

131 The tribunal stressed that the claimants’ failure to plead denial of justice in respect of the decisions of the Mexican courts was fatal: “if there is no complaint against a determination by a competent court that a contract governed by Mexican law was invalid under Mexican law, there is by definition no contract to be expropriated“: ibid., 290 (para. 100).

132 Ibid.

133 George W. Cook v. United Mexican States, Opinion of 3 June 1927, 22 AJIL 189. See also Feller, A.H., The Mexican Claims Commissions 1923-1934 (New York, Macmillan, 1935) 179–80.Google Scholar

134 United States Treaty Series, No.678;118 British & Foreign State Papers 1103.

136 Reported in F.K. Neilsen, ed., The American-Turkish Claims Settlement Commission. Opinions and Report (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1937), 490, cited in Claimant's Memorial, paras. 5.46-5.47.

137 Nielsen, 491.

138 Text in CI Bevans, Treaties and other International Agreements of the United States of America 1776-1949 (1974) vol. 11, 1105.

139 See above, para. 164.

140 Thus in the Rudloff case, the council unilaterally terminated the contract and destroyed the building the Claimant was constructing on the land in question: (1905) 9 RIAA 255, 259.

141 E.g., Libyan American Oil Company v. Government of the Libyan Arab Republic, (1977) 62 ILR 141, 189-90. See also Revere Copper & Brass, Inc. v. Overseas Private Investment Corporation (1978) 56 ILR 258.

142 See the cases reviewed by GH Aldrich, The Jurisprudence of the Iran- United States Claims Tribunal (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1996) ch. 5.

143 See, e.g., Starrett Housing Corporation v. Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1987) 16 Iran-US CTR 112, 230-1 (paras. 361-2).

144 See Shufeldt Claim, (1930) 2 RIAA 1083, 1097. This was a case of legislative invalidation of a concession agreement 6 years after its inception.

145 Article 201 defines “measure” as including “any law, regulation, procedure, requirement or practice”.

146 Cf. Marvin Feldman v. Mexico, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/99/l, Award of 16 December 2002, para. 111.

147 See above, para. 118-132 for an analysis of the remedies sought by Acaverde in the context of Article 1105.

148 Waste Management, Inc.v.United Mexican States, Award, 2 June 2000, 5 ICSID Reports 443, 461-2.

- 3

- Cited by