No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

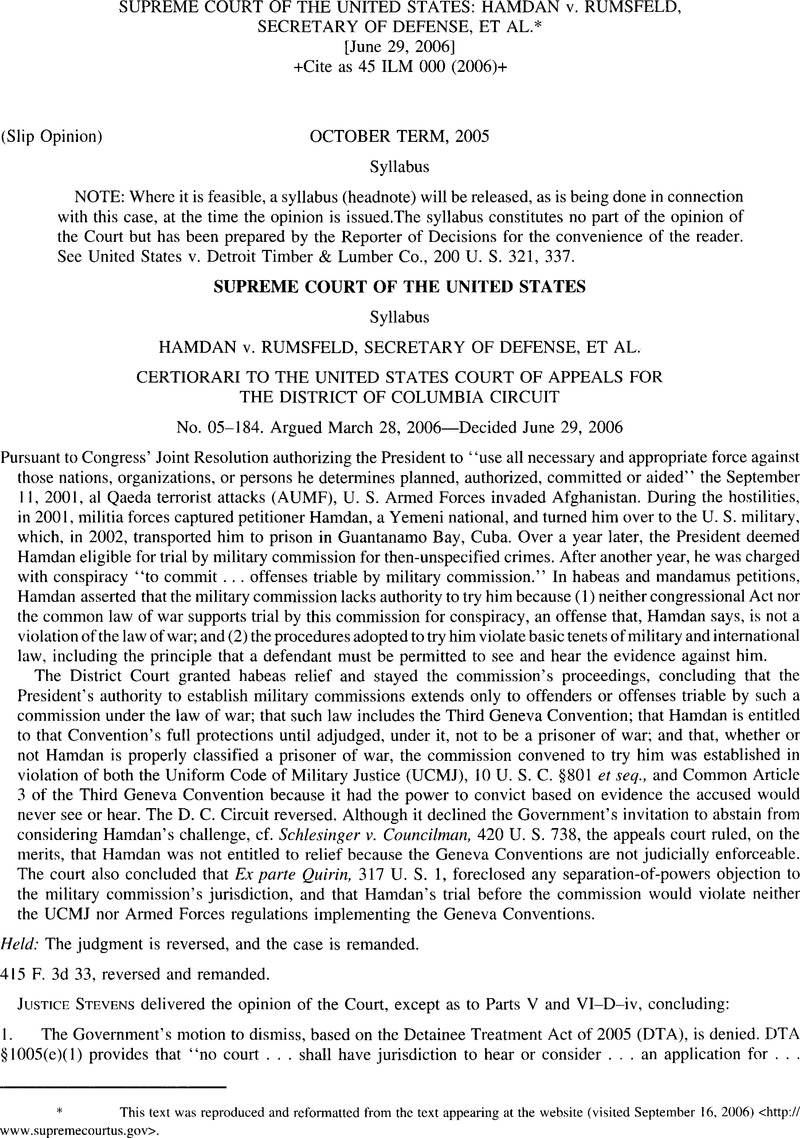

Supreme Court of the United States: Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, Secretary Of Defense, et al.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2006

References

Endnotes

* This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the website (visited September 16, 2006) <http://www.supremecourtus.gov>.

1 An “enemy combatant” is defined by the military order as “an individual who was part of or supporting Taliban or al Qaeda forces, or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners.'’ Memorandum from Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz re: Order Establishing Combatant Status Review Tribunal §a (Jul. 7,2004), available at <http://www.defense link.mil/news/ Jul2004/d20040707review.pdf> (all Internet materials as visited June 26, 2006, and available in Clerk of Court's case file).

2 The military order referenced in this section is discussed further in Parts III and VI, infra.

3 The penultimate subsections of § 1005 emphasize that the provision does not “confer any constitutional right on an alien detained as an enemy combatant outside the United States” and that the “United States” does not, for purposes of §1005, include Guantanamo Bay. §§1005(f)-(g).

4 '’ ‘And be it further enacted, That so much of the act approved February 5, 1867, entitled “An act to amend an act to establish the judicial courts of the United States, approved September 24, 1789,” as authorized an appeal from the judgment of the Circuit Court to the Supreme Court of the United States, or the exercise of any such jurisdiction by said Supreme Court, on appeals which have been, or may hereafter be taken, be, and the same is hereby repealed.’ “ 7 Wall., at 508.

5 SeeHughes Aircraft Co. v. United States ex rel. Schumer, 520 U. S. 939, 951 (1997) (“The fact that courts often apply newly enacted jurisdiction-allocating statutes to pending cases merely evidences certain limited circumstances failing to meet the conditions for our generally applicable presumption against retroactivity …“).

6 Cf.Hughes Aircraft, 520 U. S., at 951 (“Statutes merely addressing which court shall have jurisdiction to entertain a particular cause of action can fairly be said merely to regulate the secondary conduct of litigation and not the underlying primary conduct of the parties” (emphasis in original)).

7 In his insistence to the contrary, Justice Scalia reads too much into Bruner v. United States, 343 U. S. 112 (1952), Hallowell v. Commons, 239 U. S. 506 (1916), and Insurance Co. v. Ritchie, 5 Wall. 541 (1867). See post, at 2-4 (dissenting opinion). None of those cases says that the absence of an express provision reserving jurisdiction over pending cases trumps or renders irrelevant any other indications of congressional intent. Indeed, Bruner itself relied on such other indications- including a negative inference drawn from the statutory text, cf. infra, at 13-to support its conclusion that jurisdiction was not available. The Court observed that (1) Congress had been put on notice by prior lower court cases addressing the Tucker Act that it ought to specifically reserve jurisdiction over pending cases, see 343 U. S., at 115, and (2) in contrast to the congressional silence concerning reservation of jurisdiction, reservation had been made of “ ‘any rights or liabilities’ existing at the effective date of the Act'’ repealed by another provision of the Act, ibid., n. 7.

8 The question in Lindh was whether new limitations on the availability of habeas relief imposed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), 110 Stat. 1214, applied to habeas actions pending on the date of AEDPA's enactment. We held that they did not. At the outset, we reject the State's argument that, in the absence of a clear congressional statement to the contrary, a “procedural” rule must apply to pending cases. 521 U. S., at 326.

9 That paragraph (1), along with paragraphs (2) and (3), is to “take effect on the date of enactment,” DTA §1005(h)(l), 119 Stat. 2743, is not dispositive; “a ‘statement that a statute will become effective on a certain date does not even arguably suggest that it has any application to conduct that occurred at an earlier date.’ “ INS v. St. Cyr, 533 U. S. 289, 317 (2001) (quoting Landgrafv. USI Film Products, 511 U. S. 244, 257 (1994)). Certainly, the “effective date” provision cannot bear the weight Justice Scalia would place on it. See post, at 5, and n. 1. Congress deemed that provision insufficient, standing alone, to render subsections (e)(2) and (e)(3) applicable to pending cases; hence its adoption of subsection (h)(2). Justice Scalia seeks to avoid reducing subsection (h)(2) to a mere redundancy—a consequence he seems to acknowledge must otherwise follow from his interpretation—by speculating that Congress had special reasons, not also relevant to subsection (e)(l), to worry that subsections (e)(2) and (e)(3) would be ruled inapplicable to pending cases. As we explain infra, at 17, and n. 12, that attempt fails.

10 We note that statements made by Senators preceding passage of the Act lend further support to what the text of the DTA and its drafting history already make plain. Senator Levin, one of the sponsors of the final bill, objected to earlier versions of the Act's “effective date” provision that would have made subsection (e)(l) applicable to pending cases. See,e.g., 151 Cong. Rec. S12667 (Nov. 10, 2005) (amendment proposed by Sen. Graham that would have rendered what is now subsection (e)(l) applicable to “any application or other action that is pending on or after the date of the enactment of this Act“». Senator Levin urged adoption of an alternative amendment that “would apply only to new habeas cases filed after the date of enactment.” Id., at S12802 (Nov. 15, 2005). That alternative amendment became the text of subsection (h)(2). (In light of the extensive discussion of the DTA's effect on pending cases prior to passage of the Act, See,e.g., id., at S12664 (Nov. 10, 2005); id., at SI2755 (Nov. 14, 2005); id, at S12799-S12802 (Nov. 15, 2005); id., at S14245, S14252- S14253, S14257-S14258, S14274-S14275 (Dec. 21, 2005), it cannot be said that the changes to subsection (h)(2) were inconsequential. Cf. post, at 14 (SCALIA, J., dissenting).) While statements attributed to the final bill's two other sponsors, Senators Graham and Kyi, arguably contradict Senator Levin's contention that the final version of the Act preserved jurisdiction over pending habeas cases, see 151 Cong. Rec. S14263-S14264 (Dec. 21,2005), those statements appear to have been inserted into the Congressional Record after the Senate debate. See Reply Brief for Petitioner 5, n. 6; see also 151 Cong. Rec. S14260 (statement of Sen. Kyi) (“I would like to say a few words about the now completed National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2006” (emphasis added)). All statements made during the debate itself support Senator Levin's understanding that the final text of the DTA would not render subsection (e)( 1) applicable to pending cases. See,e.g., id., at S14245, S14252-S14253, S14274-S14275 (Dec. 21, 2005). The statements that Justice Scalia cites as evidence to the contrary construe subsection (e)(3) to strip this Court of jurisdiction, see post, at 12, n. 4 (dissenting opinion) (quoting 151 Cong. Rec.S 12796 (Nov. 15, 2005) (statement of Sen. Specter))—a construction that the Government has expressly disavowed in this litigation, see n. 11,infra. The inapposite November 14,2005, statement of Senator Graham, which Justice Scalia cites as evidence of that Senator's “assumption that pending cases are covered,” post, at 12, and n. 3 (citing 151 Cong. Rec. S12756 (Nov. 14, 2005)), follows directly after the uncontradicted statement of his co-sponsor, Senator Levin, assuring members of the Senate that ‘ ‘the amendment will not strip the courts of jurisdiction over [pending] cases.” Id., at S12755.

11 The District of Columbia Circuit's jurisdiction, while ‘ ‘exclusive” in one sense, would not bar this Court's review on appeal from a decision under the DTA. See Reply Brief in Support of Respondents’ Motion to Dismiss 16-17, n. 12 (“While the DTA does not expressly call for Supreme Court review of the District of Columbia Circuit's decisions, Section 1005(e)(2) and (3)… do not remove this Court's jurisdiction over such decisions under 28 U. S. C. §1254(1)“).

12 This assertion is itself highly questionable. The cases that Justice Scalia cites to support his distinction are Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U. S. 677 (2004), and Hughes Aircraft Co. v. United States ex rel Schumer, 520 U. S. 939 (1997). See post, at 8. While the Court in both of those cases recognized that statutes “creating” jurisdiction may have retroactive effect if they affect “substantive” rights, see Altmann, 541 U. S., at 695, and n. 15; Hughes Aircraft, 520 U. S., at 951, we have applied the same analysis to statutes that have jurisdiction-stripping effect, see Lindh v. Murphy, 521 U. S. 320, 327-328 (1997); id., at 342-343 (Rehnquist, C. J., dissenting) (construing AEDPA's amendments as “ousting jurisdiction“).

13 See Landgraf, 511 U. S., at 271, n. 25 (observing that “the great majority of our decisions relying upon the antiretroactivity presumption have involved intervening statutes burdening private parties,” though “we have applied the presumption in cases involving new monetary obligations that fell only on the government” (emphasis added)); see also Altmann, 541 U. S., at 728-729 (Kennedy, J., dissenting) (explaining that if retroactivity concerns do not arise when a new monetary obligation is imposed on the United States it is because “Congress, by virtue of authoring the legislation, is itself fully capable of protecting the Federal Government from having its rights degraded by retroactive laws“).

14 There may be habeas cases that were pending in the lower courts at the time the DTA was enacted that do qualify as challenges to “final decision[s]” within the meaning of subsection (e)(2) or (e)(3). We express no view about whether the DTA would require transfer of such an action to the District of Columbia Circuit.

15 Because we conclude that §1005(e)(l) does not strip federal courts’ jurisdiction over cases pending on the date of the DTA's enactment, we do not decide whether, if it were otherwise, this Court would nonetheless retain jurisdiction to hear Hamdan's appeal. Cf. supra, at 10. Nor do we decide the manner in which the canon of constitutional avoidance should affect subsequent interpretation of the DTA. See,e.g., St. Cyr, 533 U. S., at 300 (a construction of a statute “that would entirely preclude review of a pure question of law by any court would give rise to substantial constitutional questions“).

16 Councilman distinguished service personnel from civilians, whose challenges to ongoing military proceedings are cognizable in federal court. See,e.g., United States ex rel. Toth v. Quarles, 350 U. S. 11 (1955). As we explained in Councilman, abstention is not appropriate in cases in which individuals raise ‘’ ‘substantial arguments denying the right of the military to try them at all,’ ‘’ and in which the legal challenge ‘ ‘turn[s] on the status of the persons as to whom the military asserted its power.” 420 U. S., at 759 (quoting Noyd v. Bond, 395 U. S. 683, 696, n. 8 (1969)). In other words, we do not apply Councilman abstention when there is a substantial question whether a military tribunal has personal jurisdiction over the defendant. Because we conclude that abstention is inappropriate for a more basic reason, we need not consider whether the jurisdictional exception recognized in Councilman applies here.

17 See also Noyd, 395 U. S., at 694-696 (noting that the Court of Military Appeals consisted of “disinterested civilian judges,” and concluding that there was no reason for the Court to address an Air Force Captain's argument that he was entitled to remain free from confinement pending appeal of his conviction by court-martial “when the highest military court stands ready to consider petitioner's arguments“). Cf. Parisi v. Davidson, 405 U. S. 34, 41-3 (1972) (“Under accepted principles of comity, the court should stay its hand only if the relief the petitioner seeks … would also be available to him with reasonable promptness and certainty through the machinery of the military judicial system in its processing of the court- martial charge“).

18 If he chooses, the President may delegate this ultimate decision-making authority to the Secretary of Defense. See §6(H)(6).

19 Justice Scalia chides us for failing to include the District of Columbia Circuit's review powers under the DTA in our description of the review mechanism erected by Commission Order No. 1. See post, at 22. Whether or not the limited review permitted under the DTA may be treated as akin to the plenary review exercised by the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, petitioner here is not afforded a right to such review. See infra, at 52; §1005(e)(3), 119 Stat. 2743.

20 Having correctly declined to abstain from addressing Hamdan's challenge to the lawfulness of the military commission convened to try him, the Court of Appeals suggested that Councilman abstention nonetheless applied to bar its consideration of one of Hamdan's arguments—namely, that his commission violated Article 3 of the Third Geneva Convention, 6 U. S. T. 3316, 3318. See Part VI, infra. Although the Court of Appeals rejected the Article 3 argument on the merits, it also stated that, because the challenge was not “jurisdictional,” it did not fall within the exception that Schlesinger v. Councilman, 420 U. S. 738 (1975), recognized for defendants who raise substantial arguments that a military tribunal lacks personal jurisdiction over them. See 415 F. 3d, at 42. In reaching this conclusion, the Court of Appeals conflated two distinct inquiries: (1) whether Hamdan has raised a substantial argument that the military commission lacks authority to try him; and, more fundamentally, (2) whether the comity considerations underlying Councilman apply to trigger the abstention principle in the first place. As the Court of Appeals acknowledged at the beginning of its opinion, the first question warrants consideration only if the answer to the second is yes. See 415 F. 3d, at 36-37. Since, as the Court of Appeals properly concluded, the answer to the second question is in fact no, there is no need to consider any exception. At any rate, it appears that the exception would apply here. As discussed in Part VI, infra, Hamdan raises a substantial argument that, because the military commission that has been convened to try him is not a “ ‘regularly constituted court’ “ under the Geneva Conventions, it is ultra vires and thus lacks jurisdiction over him. Brief for Petitioner 5

21 See also Winthrop 831 (“[I]n general, it is those provisions of the Constitution which empower Congress to ‘declare war’ and ‘raise armies,’ and which, in authorizing the initiation of war, authorize the employment of all necessary and proper agencies for its due prosecution, from which this tribunal derives its original sanction” (emphasis in original)).

22 Article 15 was first adopted as part of the Articles of War in 1916. See Act of Aug. 29, 1916, ch. 418, §3, Art. 15, 39 Stat. 652. When the Articles of War were codified and reenacted as the UCMJ in 1950, Congress determined to retain Article 15 because it had been “construed by the Supreme Court (Ex Parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1 (1942)).” S. Rep. No. 486, 81st Cong., 1st Sess., 13 (1949).

23 Whether or not the President has independent power, absent congressional authorization, to convene military commissions, he may not disregard limitations that Congress has, in proper exercise of its own war powers, placed on his powers. See Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S. 579, 637 (1952) (Jackson, J., concurring). The Government does not argue otherwise.

24 On this point, it is noteworthy that the Court in Ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1 (1942), looked beyond Congress’ declaration of war and accompanying authorization for use of force during World War II, and relied instead on Article of War 15 to find that Congress had authorized the use of military commissions in some circumstances. See id., at 26-29. Justice Thomas’ assertion that we commit “error” in reading Article 21 of the UCMJ to place limitations upon the President's use of military commissions, see post, at 5 (dissenting opinion), ignores the reasoning in Quirin.

25 The justification for, and limitations on, these commissions were summarized in Milligan: “If, in foreign invasion or civil war, the courts are actually closed, and it is impossible to administer criminal justice according to law, then, on the theatre of active military operations, where war really prevails, there is a necessity to furnish a substitute for the civil authority, thus overthrown, to preserve the safety of the army and society; and as no power is left but the military, it is allowed to govern by martial rule until the laws can have their free course. As necessity creates the rule, so it limits its duration; for, if this government is continued after the courts are reinstated, it is a gross usurpation of power. Martial rule can never exist where the courts are open, and in the proper and unobstructed exercise of their jurisdiction. It is also confined to the locality of actual war.” 4 Wall., at 127 (emphases in original).

26 The limitations on these occupied territory or military government commissions are tailored to the tribunals’ purpose and the exigencies that necessitate their use. They may be employed “pending the establishment of civil government,” Madsen, 343 U. S., at 354-355, which may in some cases extend beyond the “cessation of hostilities,” id., at 348.

27 So much may not be evident on cold review of the Civil War trials often cited as precedent for this kind of tribunal because the commissions established during that conflict operated as both martial law or military government tribunals and law-of-war commissions. Hence, “military commanders began the practice [during the Civil War] of using the same name, the same rules, and often the same tribunals” to try both ordinary crimes and war crimes. Bickers, 34 Tex. Tech. L. Rev., at 908. “For the first time, accused horse thieves and alleged saboteurs found themselves subject to trial by the same mili tary commission.” Id., at 909. The Civil War precedents must therefore be considered with caution; as we recognized in Quirin, 317 U. S., at 29, and as further discussed below, commissions convened during time of war but under neither martial law nor military government may try only offenses against the law of war.

28 If the commission is established pursuant to martial law or military government, its jurisdiction extends to offenses committed within ‘ ‘the exercise of military government or martial law.” Winthrop 837.

29 Winthrop adds as a fifth, albeit not-always-complied-with, criterion that “the trial must be had within the theatre of war …; that, if held elsewhere, and where the civil courts are open and available, the proceedings and sentence will be coram non judice.” Id., at 836. The Government does not assert that Guantanamo Bay is a theater of war, but instead suggests that neither Washington, D. C, in 1942 nor the Philippines in 1945 qualified as a “war zone” either. Brief for Respondents 27; cf. Quirin, 317 U. S. 1; In re Yamashita, 327 U. S. 1 (1946).

30 The elements of this conspiracy charge have been defined not by Congress but by the President. See Military Commission Instruction No. 2, 32 CFR §11.6 (2005).

31 Justice Thomas would treat Osama bin Laden's 1996declaration of jihad against Americans as the inception of the war. See post, at 7-10 (dissenting opinion). But even the Government does not go so far; although the United States had for some time prior to the attacks of September 11, 2001, been aggressively pursuing al Qaeda, neither in the charging document nor in submissions before this Court has the Government asserted that the President's war powers were activated prior to September 11,2001. Cf. Brief for Respondents 25 (describing the events of September 11, 2001, as “an act of war” that “triggered a right to deploy military forces abroad to defend the United States by combating al Qaeda“). Justice Thomas‘ further argument that the AUMF is ‘ ‘backward looking’ ‘ and therefore authorizes trial by military commission of crimes that occurred prior to the inception of war is insupportable. See post, at 8, n. 3. If nothing else, Article 21 of the UCMJ requires that the President comply with the law of war in his use of military commissions. As explained in the text, the law of war permits trial only of offenses “committed within the period of the war.” Winthrop 837; see also Quirin, 317 U. S., at 28-29 (observing that law-of-war military commissions may be used to try “those enemies who in their attempt to thwart or impede our military effort have violated the law of war” (emphasis added)). The sources that Justice Thomas relies on to suggest otherwise simply do not support his position. Colonel Green's short exegesis on military commissions cites Howland for the proposition that “[o]ffenses committed before a formal declaration of war or before the. declaration of martial law may be tried by military commission.” The Military Commission, 42 Am. J. Int'l L. 832, 848(1948) (emphases added) (cited post, at 9-10). Assuming that to be true, nothing in our analysis turns on the admitted absence of either a formal declaration of war or a declaration of martial law. Our focus instead is on the September 11, 2001 attacks that the Government characterizes as the relevant ‘ ‘act[s] of war,'’ and on the measure that authorized the President's deployment of military force—the AUMF. Because we do not question the Government's position that the war commenced with the events of September 11, 2001, the Prize Cases, 2 Black 635 (1863) (cited post, at 2, 7, 8, and 10 (THOMAS, J., dissenting)), are not germane to the analysis. Finally, Justice Thomas” assertion that Julius Otto Kuehn’ s trial by military commission “for conspiring with Japanese officials to betray the United States fleet to the Imperial Japanese Government prior to its attack on Pearl Harbor'’ stands as authoritative precedent for Hamdan's trial by commission, post, at 9, misses the mark in three critical respects. First, Kuehn was tried for the federal espionage crimes under what were then 50 U. S C. §§31, 32, and 34, not with common-law violations of the law of war. See Hearings before the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, 79th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 30, pp. 3067-3069 (1946). Second, he was tried by martial law commission (a kind of commission Justice Thomas acknowledges is not relevant to the analysis here, and whose jurisdiction extends to offenses committed within “the exercise of… martial law,” Winthrop 837, see supra, n. 28), not a commission established exclusively to try violations of the law of war. See ibid. Third, the martial law commissions established to try crimes in Hawaii were ultimately declared illegal by this Court. See Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U. S. 304,324 (1946) (“Thephrase ‘martial law’ as employed in [the Hawaiian Organic Act], while intended to authorize the military to act vigorously for the maintenance of an orderly civil government and for the defense of the Islands against actual or threatened rebellion or invasion, was not intended to authorize the supplanting of courts by military tribunals“).

32 Justice Thomas adopts the remarkable view, not advocated by the Government, that the charging document in this case actually includes more than one charge: Conspiracy and several other ill defined crimes, like “joining an organization” that has a criminal purpose, “ ‘[b]eing a guerilla,’ “ and aiding the enemy. See post, at 16-21, and n. 9. There are innumerable problems with this approach. First, the crimes Justice Thomas identifies were not actually charged. It is one thing to observe that charges before a military commission “need not be stated with the precision of a common law indictment,’ “ post, at 15, n. 7 (citation omitted); it is quite another to say that a crime not charged may nonetheless be read into an indictment. Second, the Government plainly had available to it the tools and the time it needed to charge petitioner with the various crimes Justice Thomas refers to, if it believed they were supported by the allegations. As Justice Thomas himself observes, see post, at 21, the crime of aiding the enemy may, in circumstances where the accused owes allegiance to the party whose enemy he is alleged to have aided, be triable by military commission pursuant to Article 104 of the UCMJ, 10 U. S. C. §904. Indeed, the Government has charged detainees under this provision when it has seen fit to do so. See Brief for David Hicks as Amicus Curiae 1.Third, the cases Justice Thomas relies on to show that Hamdan may be guilty of violations of the law of war not actually charged do not support his argument. Justice Thomas begins by blurring the distinction between those categories of “offender” who may be tried by military commission (e.g., jayhawkers and the like) with the “offenses” that may be so tried. Even when it comes to “ ‘being a guerilla,’ “ cf. post, at 18, n. 9 (citation omitted), a label alone does not render a person susceptible to execution or other criminal punishment; the charge of “ ‘being a guerilla’ “ invariably is accompanied by the allegation that the defendant “ ‘took up arms’ “ as such. This is because, as explained by Judge Advocate General Holt in a decision upholding the charge of “ ‘being a guerilla’ “ as one recognized by “the universal usage of the times,” the charge is simply shorthand (akin to “being a spy“) for “the perpetration of a succession of similar acts” of violence. Record Books of the Judge Advocate General Office, R. 3, 590. The sources cited by Justice Thomas confirm as much. See cases cited port, at 18, n. 9. Likewise, the suggestion that the Nuremberg precedents support Hamdan's conviction for the (uncharged) crime of joining a criminal organization must fail. Cf. post, at 19-21. The convictions of certain high-level Nazi officials for ‘ ‘membership in a criminal organization'’ were secured pursuant to specific provisions of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal that permitted indictment of individual organization members following convictions of the organizations themselves. See Arts. 9 and 10, in 1 Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal 12 (1947). The initial plan to use organizations’ convictions as predicates for mass individual trials ultimately was abandoned. See T. Taylor, Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir 584-585, 638 (1992).

33 Cf. 10 U. S. C. §904 (making triable by military commission the crime of aiding the enemy); §906 (same for spying); War Crimes Act of 1996, 18 U. S. C. §2441 (2000 ed. and Supp.III) (listing war crimes); Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Appropriations Act, 1998, §583, 111 Stat. 2436 (same).

34 While the common law necessarily is “evolutionary in nature,” port, at 13 (THOMAS, J., dissenting), even in jurisdictions where common law crimes are still part of the penal framework, an act does not become a crime without its foundations having been firmly established in precedent. See,e.g., R. v. Rimmington, [2006] 2 All E. R. 257, 275-279 (House of Lords); id., at 279 (while “some degree of vagueness is inevitable and development of the law is a recognised feature of common law courts,… the law-making function of the courts must remain within reasonable limits“); see also Rogers v. Tennessee, 532 U. S. 451, 472 - 478 (2001) (SCALIA, J., dissenting). The caution that must be exercised in the incremental development of common-law crimes by the judiciary is, for the reasons explained in the text, all the more critical when reviewing developments that stem from military action.

35 The 19th-century trial of the “Lincoln conspirators,” even if properly classified as a trial by law-of-war commission, cf. W. Rehnquist, All the Laws But One: Civil Liberties in Wartime 165 - 167 (1998) (analyzing the conspiracy charges in light of ordinary criminal law principles at the time), is at best an equivocal exception. Although the charge against the defendants in that case accused them of “combining, confederating, and conspiring together” to murder the President, they were also charged (as we read the indictment, cf. post, at 23, n. 14 (THOMAS, J., dissenting)) with “maliciously, unlawfully, and traitorously murdering the said Abraham Lincoln.” H. R. Doc. No. 314, 55th Cong., 1st Sess., 696 (1899). Moreover, the Attorney General who wrote the opinion defending the trial by military commission treated the charge as if it alleged the substantive offense of assassination. See 11 Op. Atty. Gen. 297 (1865) (analyzing the propriety of trying by military commission “the offence of having assassinated the President“); see also Mudd v. Caldera, 134 F. Supp. 2d 138, 140 (DC 2001).

36 By contrast, the Geneva Conventions do extend liability for substantive war crimes to those who “orde[r]” their commission, see Third Geneva Convention, Art. 129, 6 U. S. T., at 3418, and this Court has read the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 to impose “command responsibility” on military commanders for acts of their subordinates, see Yamshita, ill U. S., at 15-16.

37 The other examples Justice Thomas offers are no more availing. The Civil War indictment against Robert Louden, cited post, at 25, alleged a conspiracy, but not one in violation ofthe law of war. See War Dept., General Court Martial Order No. 41, p. 20 (1864). A separate charge of “‘[transgression of the laws and customs of war''’ made no mention of conspiracy. Id., at 17. The charge against Lenger Grenfel and others for conspiring to release rebel prisoners held in Chicago only supports the observation, made in the text, that the Civil War tribunals often charged hybrid crimes mixing elements of crimes ordinarily triable in civilian courts (like treason) and violations of the law of war. Judge Advocate General Holt, in recommending that Grenfel's death sentence be upheld (it was in fact commuted by Presidential decree, see H. R. Doc. No. 314, at 725), explained that the accused “united himself with traitors and malefactors for the overthrow of our Republic in the interest of slavery.” Id., at 689.

38 The Court in Quirin “assume[d] that there are acts regarded in other countries, or by some writers on international law, as offenses against the law of war which would not be triable by military tribunal here, either because they are not recognized by our courts as violations of the law of war or because they are of that class of offenses constitutionally triable only by a jury.” 317 U. S., at 29. We need not test the validity of that assumption here because the international sources only corroborate the domestic ones.

39 Accordingly, the Tribunal determined to “disregard the charges … that the defendants conspired to commit War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity.” 22 Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal 469 (1947); see also ibid. (“[T]he Charter does not define as a separate crime any conspiracy except the one to commit acts of aggressive war“).

40 See also 15 United Nations War Crimes Commissions, Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals 90-91 (1949) (observing that, although a few individuals were charged with conspiracy under European domestic criminal codes following World War II, “the United States Military Tribunals” established at that time did not’ ‘recognis[e] as a separate offence conspiracy to commit war crimes or crimes against humanity“). The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), drawing on the Nuremberg precedents, has adopted a “joint criminal enterprise” theory of liability, but that is a species of liability for the substantive offense (akin to aiding and abetting), not a crime on its own. See Prosecutor v. Tadič,Judgment, Case No. IT-94-1-A (ICTY App. Chamber, July 15, 1999); see also Prosecutor v. Milutinovič, Decision on Dragoljub Ojdanićs Motion Challenging Jurisdiction—Joint Criminal Enterprise, Case No. IT-99-37-AR72,¶26 (ICTY App. Chamber, May 21, 2003) (stating that “[c]riminal liability pursuant to ajoint criminal enterprise is not a liability for … conspiring to commit crimes“).

41 Justice Thomas suggestion that our conclusion precludes the Government from bringing to justice those who conspire to commit acts of terrorism is therefore wide of the mark. See post, at 8, n. 3; 28-30. That conspiracy is not a violation of the law of war triable by military commission does not mean the Government may not, for example, prosecute by courtmartial or in federal court those caught “plotting terrorist atrocities like the bombing of the Khobar Towers.” Post, at 29.

42 The accused also may be excluded from the proceedings if he “engages in disruptive conduct.” §5(K).

43 As the District Court observed, this section apparently permits reception of testimony from a confidential informant in circumstances where “Hamdan will not be permitted to hear the testimony, see the witness's face, or learn his name. If the government has information developed by interrogation of witnesses in Afghanistan or elsewhere, it can offer such evidence in transcript form, or even as summaries of transcripts.” 344 F. Supp. 2d 152, 168 (DC 2004).

44 Any decision of the commission is not “final” until the President renders it so. See Commission Order No. 1 §6(H)(6).

45 See Winthrop 835, and n. 81 (“military commissions are constituted and composed, and their proceedings are conducted, similarly to general courts-martial“); id., at 841-842; S. Rep. No. 130, 64th Cong., 1st Sess., 40 (1916) (testimony of Gen. Crowder) (“Both classes of courts have the same procedure“); see also, e.g., H. Coppee, Field Manual of Courts-Martial, p. 104 (1863) (“[Military] commissions are appointed by the same authorities as those which may order courts-martial. They are constituted in a manner similar to such courts, and their proceedings are conducted in exactly the same way, as to form, examination of witnesses, etc.“).

46 The dissenters’ views are summarized in the following passage: “It is outside our basic scheme to condemn men without giving reasonable opportunity for preparing defense; in capital or other serious crimes to convict on ‘official documents …; affidavits;…documents or translations thereof; diaries .. ., photographs, motion picture films, and … newspapers “ or on hearsay, once, twice or thrice removed, more particularly when the documentary evidence or some of it is prepared ex parte by the prosecuting authority and includes not only opinion but conclusions of guilt. Nor in such cases do we deny the rights of confrontation of witnesses and cross examination.” Yamashita, 327 U. S., at 44 (footnotes omitted).

47 Article 2 of the UCMJ now reads: “(a) The following persons are subject to [the UCMJ]: “(9) Prisoners of war in custody of the armed forces “(12) Subject to any treaty or agreement to which the United States is or may be a party or to any accepted rule of international law, persons within an area leased by or otherwise reserved or acquired for the use of the United States which is under the control of the Secretary concerned and which is outside the United States and outside the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands.” 10 U. S. C. §802(a). Guantanamo Bay is such a leased area. See Rasul v. Bush, 542 U. S. 466, 471 (2004).

48 The International Committee of the Red Cross is referred to by name in several provisions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and is the body that drafted and published the official commentary to the Conventions. Though not binding law, the commentary is, as the parties recognize, relevant in interpreting the Conventions’ provisions.

49 Aside from Articles 21 and 36, discussed at length in the text, the other seven Articles that expressly reference military commissions are: (1) 28 (requiring appointment of reporters and interpreters); (2) 47 (making it a crime to refuse to appear or testify ‘ ‘before a court-martial, military commission, court of inquiry, or any other military court or board“); (3) 48 (allowing a ‘ ‘court-martial, provost court, or military commission” to punish a person for contempt); (4) 49(d) (permitting admission into evidence of a “duly authenticated deposition taken upon reasonable notice to the other parties” only if “admissible under the rules of evidence” and only if the witness is otherwise unavailable); (5) 50 (permitting admission into evidence of records of courts of inquiry “if otherwise admissible under the rules of evidence,” and if certain other requirements are met); (6) 104 (providing that a person accused of aiding the enemy may be sentenced to death or other punishment by military commission or court-martial); and (7) 106 (mandating the death penalty for spies convicted before military commission or court martial).

50 Justice Thomas relies on the legislative history of the UCMJ to argue that Congress’ adoption of Article 36(b) in the wake of World War II was “motivated” solely by a desire for ‘ ‘uniformity across the separate branches of the armed services.” Post, at 35. But even if Congress was concerned with ensuring uniformity across service branches, that does not mean it did not also intend to codify the longstanding practice of procedural parity between courts-martial and other military tribunals. Indeed, the suggestion that Congress did not intend uniformity across tribunal types is belied by the textual proximity of subsection (a) (which requires that the rules governing criminal trials in federal district courts apply, absent the President's determination of impracticability, to courts-martial, provost courts, and military commissions alike) and subsection (b) (which imposes the uniformity requirement).

51 We may assume that such a determination would be entitled to a measure of deference. For the reasons given by Justice Kennedy, see. post, at 5 (opinion concurring in part), however, the level of deference accorded to a determination made under subsection (b) presumably would not be as high as that accorded to a determination under subsection (a).

52 Justice Thomas looks not to the President's official Article 36(a) determination, but instead to press statements made by the Secretary of Defense and the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy. See post, at 36-38 (dissenting opinion). We have not heretofore, in evaluating the legality of Executive action, deferred to comments made by such officials to the media. Moreover, the only additional reason the comments provide—aside from the general danger posed by international terrorism—for departures from court-martial procedures is the need to protect classified information. As we explain in the text, and as Justice Kennedy elaborates in his separate opinion, the structural and procedural defects of Hamdan's commission extend far beyond rules preventing access to classified information.

53 Justice Thomas relies extensively on Madsen for the proposition that the President has free rein to set the procedures that govern military commissions. See post, at 30, 31, 33, n. 16, 34, and 45. That reliance is misplaced. Not only did Madsen not involve a law-of-war military commission, but (1) the petitioner there did not challenge the procedures used to try her, (2) the UCMJ, with its new Article 36(b), did not become effective until May 31, 1951, after the petitioner's trial, see 343 U. S., at 345, n. 6, and (3) the procedures used to try the petitioner actually afforded more protection than those used in courts-martial, see id., at 358-360; see also id., at 358 (“[T]he Military Government Courts for Germany … have had a less military character than that of courts-martial“).

54 Prior to the enactment of Article 36(b), it may well have been the case that a deviation from the rules governing courts martial would not have rendered the military commission “illegal’ “ Post, at 30-31, n. 16 (THOMAS, J., dissenting) (quoting Winthrop 841). Article 36(b), however, imposes a statutory command that must be heeded.

55 Justice Thomas makes the different argument that Hamdan's Geneva Convention challenge is not yet “ripe” because he has yet to be sentenced. See post, at 43-45. This is really just a species of the abstention argument we have already rejected. See Part III, supra. The text of the Geneva Conventions does not direct an accused to wait until sentence is imposed to challenge the legality of the tribunal that is to try him.

56 As explained in Part VI-C, supra, that is no longer true under the 1949 Conventions.

57 But See,e.g., 4 Int'l Comm. of Red Cross, Commentary:Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War 21 (1958) (hereinafter GCIV Commentary) (the 1949 Geneva Conventions were written “first and foremost to protect individuals, and not to serve State interests“); GCIII Commentary 91 (“It was not… until the Conventions of 1949 … that the existence of ‘rights’ conferred in prisoners of war was affirmed“).

58 But see generally Brief for Louis Henkin et al. as Amici Curiae; 1 Int'l Comm. for the Red Cross, Commentary: Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field 84 (1952) (“It should be possible in States which are parties to the Convention … for the rules of the Convention to be evoked before an appropriate national court by the protected person who has suffered a violation“); GCII Commentary 92; GCIV Commentary 79.

59 For convenience's sake, we use citations to the Third Geneva Convention only.

60 The President has stated that the conflict with the Taliban is a conflict to which the Geneva Conventions apply. See White House Memorandum, Humane Treatment of Taliban and al Qaeda Detainees 2 (Feb. 7, 2002), available at <http:// www.justicescholars.org/pegc/archive/White_House/bush_ memo_20020207_ed.pdf> (hereinafter White House Memorandum).

61 Hamdan observes that Article 5 of the Third Geneva Convention requires that if there be ‘ ‘any doubt'’ whether he is entitled to prisoner-of-war protections, he must be afforded those protections until his status is determined by a “competent tribunal.” 6 U. S. T., at 3324. See also Headquarters Depts. Of Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps, Army Regulation 190-8, Enemy Prisoners of War, Retained Personnel, Civilian Internees and Other Detainees (1997), App. 116. Because we hold that Hamdan may not, in any event, be tried by the military commission the President has convened pursuant to the November 13 Order and Commission Order No. 1, the question whether his potential status as a prisoner of war independently renders illegal his trial by military commission may be reserved.

62 The term “Party” here has the broadest possible meaning; a Party need neither be a signatory of the Convention nor ‘ ‘even represent a legal entity capable of undertaking international obligations.” GCIII Commentary 37.

63 See also GCIII Commentary 35 (Common Article 3 ‘ ‘has the merit of being simple and clear. … Its observance does not depend upon preliminary discussions on the nature of the conflict“); GCIV Commentary 51 (“[N]obody in enemy hands can be outside the law“); U. S. Army Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School, Dept. of the Army, Law of War Handbook 144 (2004) (Common Article 3 “serves as a ‘minimum yardstick of protection in all conflicts, not just internal armed conflicts’ “ (quoting Nicaragua v. United States, 1986 I. C. J. 14, ¶218, 25 I. L. M. 1023)); Prosecutor v. Tadič, Case No. IT-94—1, Decision on the Defence Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction, ¶102 (ICTY App. Chamber, Oct. 2, 1995) (stating that “the character of the conflict is irrelevant” in deciding whether Common Article 3 applies).

64 The commentary's assumption that the terms “properly constituted“and “regularly constituted” are interchangeable is beyond reproach; the French version of Article 66, which is equally authoritative, uses the term “régulièrement constitués” in place of “properly constituted.“

65 Further evidence of this tribunal's irregular constitution is the fact that its rules and procedures are subject to change midtrial, at the whim of the Executive. See Commission Order No. 1, § 11 (providing that the Secretary of Defense may change the governing rules “from time to time“).

66 Other international instruments to which the United States is a signatory include the same basic protections set forth in Article 75. See,e.g., International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Art. 14, f3(d), Mar. 23, 1976, 999 U. N. T. S. 171 (setting forth the right of an accused “[t]o be tried in his presence, and to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing“). Following World War II, several defendants were tried and convicted by military commission for violations of the law of war in their failure to afford captives fair trials before imposition and execution of sentence. In two such trials, the prosecutors argued that the defendants’ failure to apprise accused individuals of all evidence against them constituted violations of the law of war. See 5 U. N. War Crimes Commission 30 (trial of Sergeant-Major Shigeru Ohashi), 75 (trial of General Tanaka Hisakasu).

67 The Government offers no defense of these procedures other than to observe that the defendant may not be barred from access to evidence if such action would deprive him of a “full and fair trial.” Commission Order No. 1, §6(D)(5)(b). But the Government suggests no circumstances in which it would be “fair” to convict the accused based on evidence he has not seen or heard. Cf. Crawford v. Washington, 541 U. S. 36, 49 (2004) (” ‘It is a rule of the common law, founded on natural justice, that no man shall be prejudiced by evidence which he had not the liberty to cross examine’ “ (quoting State v. Webb, 2 N. C. 103, 104 (Super. L. & Eq. 1794) (per curiam)); Diaz v. United States, 223 U. S. 442, 455 (1912) (describing the right to be present as “scarcely less important to the accused than the right of trial itself); Lewis v. United States, 146 U. S. 370, 372 (1892) (exclusion of defendant from part of proceedings is “contrary to the dictates of humanity” (internal quotation marks omitted)); Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 170, n. 17, 171 (1951) (Frankfurter, J., concurring) (“[t]he plea that evidence of guilt must be secret is abhorrent to free men” (internal quotation marks omitted)). More fundamentally, the legality of a tribunal under Common Article 3 cannot be established by bare assurances that, whatever the character of the court or the procedures it follows, individual adjudicators will act fairly

1 The Court apparently believes that the effective-date provision means nothing at all. “That paragraph (1), along with paragraphs (2) and (3), is to ‘take effect on the date of enactment,’ DTA §1005(h)(l), 119 Stat. 2743, is not dispositive,” says the Court, ante, at 14, n. 9. The Court's authority for this conclusion is its quote from INS v. St. Cyr, 533 U. S. 289, 317 (2001), to the effect that “a statement that a statute will become effective on a certain date does not even arguably suggest that it has any application to conduct that occurred at an earlier date.” Ante, at 14, n. 9 (emphasis added, internal quotation marks omitted). But this quote merely restates the obvious: An effective-date provision does not render a statute applicable to “conduct that occurred at an earlier date,” but of course it renders the statute applicable to conduct that occurs on the effective date and all future dates—such as the Court's exercise of jurisdiction here. The Court seems to suggest that, because the effective-date provision does not authorize retroactive application, it also fails to authorize prospective application (and is thus useless verbiage). This cannot be true.

2 A comparison with Lindh v. Murphy, 521 U. S. 320 (1997), shows this not to be true. Subsections (e)(2) and (e)(3) of § 1005 resemble the provisions of AEDPA at issue in Lindh (whose retroactivity as applied to pending cases the Lindh majority did not rule upon, see 521 U. S., at 326), in that they “g[o] beyond ‘mere’ procedure,” id., at 327. They impose novel and unprecedented disabilities on the Executive Branch in its conduct of military affairs. Subsection (e)(2) imposes judicial review on the Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRTs), whose implementing order did not subject them to review by Article III courts. See Memorandum from Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz re: Order Establishing Combatant Status Review Tribunals, at 3 §h (July 7, 2004), available at <http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Jul2004/ d20040707review.pdf> (all Internet materials as visited June 27, 2006, and available in Clerk of Court's case file). Subsection (e)(3) authorizes the D. C. Circuit to review “the validity of any final decision rendered pursuant to Military Commission Order No. 1,” §1005(e)(3)(A), 119 Stat. 2743. Historically, federal courts have never reviewed the validity of the final decision of any military commission; their jurisdiction has been restricted to considering the commission's “lawful authority to hear, decide and condemn,” In re Yamashita, 327 U. S. 1,8 (1946) (emphasis added). See also Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U. S. 763, 786-787 (1950). Thus, contrary to the Court's suggestion, ante, at 17, subsections (e)(2) and (e)(3) confer new jurisdiction: They impose judicial oversight on a traditionally unreviewable exercise of military authority by the Commander in Chief. They arguably “spea[k] not just to the power of a particular court but to … substantive rights … as well,” Hughes Aircraft Co. v. United States ex rel. Shumer, 520 U. S. 939,951 (1997)—namely, the unreviewable powers of the President. Our recent cases had reiterated that the Executive is protected by the presumption against retroactivity in such comparatively trivial contexts as suits for tax refunds and increased pay, see Landgrafv. USI Film Products, 511 U. S. 244, 271, n. 25 (1994).

3 ''Because I have described how outrageous these claims are— about the exercise regime, the reading materials—most Americans would be highly offended to know that terrorists are suing us in our own courts about what they read.” 151 Cong. Rec. S12756 (Nov. 14, 2005). “Instead of having unlimited habeas corpus opportunities under the Constitution, we give every enemy combatant, all 500, a chance to go to Federal court, the Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia … It will be a one-time deal.” Id., at S12754. “This Levin-Graham-Kyi amendment allows every detainee under our control to have their day in court. They are allowed to appeal their convictions.” Id., at S12801 (Nov. 15, 2005); see also id., at SI2799 (rejecting the notion that “an enemy combatant terrorist al-Qaida member should be able to have access to our Federal courts under habeas like an American citizen“).

4 “An earlier part of the amendment provides that no court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to consider the application for writ of habeas corpus… . Under the language of exclusive jurisdiction in the DC Circuit, the U. S. Supreme Court would not have jurisdiction to hear the Hamdan case . …” Id., at S12796 (statement of Sen. Specter).

5 “[T]he executive branch shall construe section 1005 to preclude the Federal courts from exercising subject matter jurisdiction over any existing or future action, including applications for writs of habeas corpus, described in section 1005.” President's Statement on Signing of H. R. 2863, the “Department of Defense, Emergency Supplemental Appropriations to Address Hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico, and Pandemic Influenza Act, 2006” (Dec. 30, 2005), available at <http:// www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2005/12/print/ 2OO5123O8.html>

6 The Court asserts that ‘ ‘it cannot be said that the changes to subsection (h)(2) were inconsequential,” ante, at 15, n. 10, but the Court's sole evidence is the self-serving floor statements that it selectively cites.

7 Petitioner also urges that he could be subject to indefinite delay if military officials and the President are deliberately dilatory in reviewing the decision of his commission. In reviewing the constitutionality of legislation, we generally presume that the Executive will implement its provisions in good faith. And it is unclear in any event that delay would inflict any injury on petitioner, who (after an adverse determination by his CSRT, see 344 F. Supp. 2d 152, 161 (DC 2004)) is already subject to indefinite detention under our decision in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U. S. 507 (2004). Moreover, the mere possibility of delay does not render an alternative remedy “inadequate [o]r ineffective to test the legality” of a military commission trial. Swain v. Pressley, 430 U. S. 372,381 (1977). In an analogous context, we discounted the notion that postponement of relief until postconviction review inflicted any cognizable injury on a serviceman charged before a military court-martial. Schlesinger v. Councilman, 420 U. S. 738,754-755 (1975); see also Younger v. Harris, 401 U. S. 37, 46 (1971). The very purpose of Article II's creation of a civilian Commander in Chief in the President of the United States was to generate “structural insulation from military influence.” See

8 The Federalist No. 28 (A. Hamilton); id., No. 69 (same). We do not live under a military junta. It is a disservice to both those in the Armed Forces and the President to suggest that the President is subject to the undue control of the military.

9 In rejecting our analysis, the Court observes that appeals to the D. C. Circuit under subsection (e)(3) are discretionary, rather than as of right, when the military commission imposes a sentence less than 10 years’ imprisonment, see ante, at 23, n. 19, 52-53; §1005(e)(3)(B), 119 Stat. 2743. The relevance of this observation to the abstention question is unfathomable. The fact that Article III review is discretionary does not mean that it lacks “structural insulation from military influence,” ante, at 23, and its discretionary nature presents no obstacle to the courts’ future review these cases. The Court might more cogently have relied on the discretionary nature of review to argue that the statute provides an inadequate substitute for habeas review under the Suspension Clause. See supra, at 16-18. But this argument would have no force, even if all appeals to the D. C. Circuit were discretionary. The exercise of habeas jurisdiction has traditionally been entirely a matter of the court's equitable discretion, see Withrow v. Williams, 507 U. S. 680, 715-718 (1993) (Scalia, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part), so the fact that habeas jurisdiction is replaced by discretionary appellate review does not render the substitution “inadequate.” Swain, 430 U. S., at 381.

1 As previously noted, Article 15 of the Articles of War was the predecessor of Article 21 of the UCMJ. Article 21 provides as follows:’ “The provisions of this chapter conferring jurisdiction upon courts-martial do not deprive military commissions, provost courts, or other military tribunals of concurrent jurisdiction with respect to offenders or offenses that by statute or by the law of war may be tried by military commissions, provost courts, or other military tribunals.” 10 U. S. C. §821.

2 Although the President very well may have inherent authority to try unlawful combatants for violations of the law of war before military commissions, we need not decide that question because Congress has authorized the President to do so. Cf. Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U. S. 507, 587 (2004) (THOMAS, J., dissenting) (same conclusion respecting detention of unlawful combatants).

3 Even if the formal declaration of war were generally the determinative act in ascertaining the temporal reach of the jurisdiction of a military commission, the AUMF itself is inconsistent with the plurality's suggestion that such a rule is appropriate in this case. See ante, at 34-36, 48. The text of the AUMF is backward looking, authorizing the use of “all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001.” Thus, the President's decision to try Hamdan by military commission—a use of force authorized by the AUMF—for Hamdan's involvement with al Qaeda prior to September 11, 2001, fits comfortably within the framework of the AUMF. In fact, bringing the September 11 conspirators to justice is the primary point of the AUMF. By contrast, on the plurality's logic, the AUMF would not grant the President the authority to try Usama bin Laden himself for his involvement in the events of September 11, 2001.

4 The plurality suggests these authorities are inapplicable because nothing in its “analysis turns on the admitted absence of either a formal declaration of war or a declaration of martial law. Our focus instead is on the … AUMF.” Ante, at 35, n. 31. The difference identified by the plurality is purely semantic. Both Green and Howland confirm that the date of the enactment that establishes a legal basis for forming military commissions—whether it be a declaration of war, a declaration of martial law, or an authorization to use military force—does not limit the jurisdiction of military commissions to offenses committed after that date.

5 The plurality attempts to evade the import of this historical example by observing that Kuehn was tried before a martial law commission for a violation of federal espionage statutes. Ibid. As an initial matter, the fact that Kuehn was tried before a martial law commission for an offense committed prior to the establishment of martial law provides strong support for the President's contention that he may try Hamdan for offenses committed prior to the enactment of the AUMF. Here the AUMF serves the same function as the declaration of martial law in Hawaii in 1941, establishing legal authority for the constitution of military commissions. Moreover, Kuehn was not tried and punished ‘ ‘by statute, but by the laws and usages of war.” United States v. Bernard Julius Otto Kuehn, Board of Review 5 (Office of the Military Governor, Hawaii 1942). Indeed, in upholding the imposition of the death penalty, a sentence “not authorized by the Espionage statutes,” ibid., Kuehn's Board of Review explained that “[t]he fact that persons may be tried and punished … by a military commission for committing acts defined as offenses by … federal statutes does not mean that such persons are being tried for violations of such … statutes; they are, instead, being tried for acts made offenses only by orders of the… commanding general.'’ Id., at 6. Lastly, the import of this example is not undermined by Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U. S. 304 (1946). The question before the Court in that case involved only whether ‘ ‘loyal civilians in loyal territory should have their daily conduct governed by military orders,” id., at 319; it did “not involve the well-established power of the military to exercise jurisdiction over … enemy belligerents,” id., at 313.

6 Indeed, respecting the present conflict, the President has found that “the war against terrorism ushers in a new paradigm, one in which groups with broad, international reach commit horrific acts against innocent civilians, sometimes with the direct support of states. Our Nation recognizes that this new paradigm—ushered in not by us, but by terrorists—requires new thinking in the law of war.” App. 34-35. Under the Court's approach, the President's ability to address this “new paradigm” of inflicting death and mayhem would be completely frozen by rules developed in the context of conventional warfare.

7 It is true that both of these separate offenses are charged under a single heading entitled “Charge: Conspiracy,” App. to Pet. for Cert. 65a. But that does not mean that they must be treated as a single crime, when the law of war treats them as separate crimes. As we acknowledged in In re Yamashita, 327 U. S. 1 (1946), “charges of violations of the law of war triable before a military tribunal need not be stated with the precision of a common law indictment.” Id., at 17; cf. W. Birkhimer, Military Government and Martial Law 536 (3d ed. 1914) (hereinafter Birkhimer) (“[I]t would be extremely absurd to expect the same precision in a charge brought before a court-martial as is required to support a conviction before a justice of the peace” (internal quotation marks omitted)). Nevertheless, the plurality contends that Hamdan was “not actually charged,” ante, at 37, n. 32 (emphasis deleted), with being a member in a war criminal organization. But that position is demonstrably wrong. Hamdan's charging document expressly charges that he “willfully and knowingly joined an enterprise of persons who shared a common criminal purpose.” App. to Pet. for Cert. 65a. Moreover, the plurality's contention that we may only look to the label affixed to the charge to determine if the charging document alleges an offense triable by military commission is flatly inconsistent with its treatment of the Civil War cases—where it accepts as valid charges that did not appear in the heading or title of the charging document, or even the listed charge itself, but only in the supporting specification. See,e.g., ante, at 45-46 (discussing the military commission trial of Wirz). For example, in the Wirz case, Wirz was charged with conspiring to violate the laws of war, and that charge was supported with allegations that he personally committed a number of atrocities. The plurality concludes that military commission jurisdiction was appropriate in that case not based upon the charge of conspiracy, but rather based upon the allegations of various atrocities in the specification which were not separately charged. Ante, at 45. Just as these atrocities, not separately charged, were independent violations of the law of war supporting Wirz's trial by military commission, so too here Hamdan's membership in al Qaeda and his provision of various forms of assistance to al Qaeda's top leadership are independent violations of the law of war supporting his trial by military commission.

8 These observations respecting the law of war were made by the Attorney General in defense of the military commission trial of the Lincoln conspirators'. As the foregoing quoted portion of that opinion makes clear, the Attorney General did not, as the Court maintains, “trea[t] the charge as if it alleged the substantive offense of assassination.” Ante, at 40, n. 35. Rather, he explained that the conspirators “high offence against the laws of war” was “complete” when their band was “organized or joined,” and did not depend upon “atrocities committed by such a band.” 11 Op. Atty. Gen. 297, 312 (1865). Moreover, the Attorney General's conclusions specifically refute the plurality's unsupported suggestion that I have blurred the line between “those categories of ‘offender’ who may be tried by military commission . .. with the ‘offenses’ that may be so tried.” Ante, at 37, n. 32.

9 The General Orders establishing the jurisdiction for military commissions during the Civil War provided that such offenses were violations of the laws of war cognizable before military commissions. See H. R. Doc. No. 65, 55th Cong., 3d Sess., 164 (1894) (“[P]ersons charged with the violation of the laws of war as spies, bridge-burners, marauders, &c, will … be held for trial under such charges“); id., at 234 (“[T]here are numerous rebels … that … furnish the enemy with arms, provisions, clothing, horses and means of transportation; [such] insurgents are banding together in several of the interior counties for the purpose of assisting the enemy to rob, to maraud and to lay waste to the country. All such persons are by the laws of war in every civilized country liable to capital punishment” (emphasis added)). Numerous trials were held under this authority. See,e.g., U. S. War Dept., General Court-Martial Order No. 51, p. 1 (1866) (hereinafter G. C. M. O.). (indictment in the military commission trial of James Harvey Wells charged “[b]eing a guerrilla” and specified that he “willfully .. . [took] up arms as a guerrilla marauder, and did join, belong to, act and co-operate with guerrillas“); G. C. M. O. No. 108, Head-Quarters Dept. of Kentucky, p. 1 (1865) (indictment in the military commission trial of Henry C. Magruder charged “[b]eing a guerrilla” and specified that he “unlawfully, and of his own wrong, [took] up arms as a guerrilla marauder, and did join, belong to, act, and co-operate with a band of guerrillas“); G. C. M. O. No. 41, p. 1 (1864) (indictment in the military commission trial of John West Wilson charged that Wilson “did take up arms as an insurgent and guerrilla against the laws and authorities of the United States, and did join and co-operate with an armed band of insurgents and guerrillas who were engaged in plundering the property of peaceable citizens … in violation of the laws and customs of war“); G. C. M. O. No. 153, p. 1 (1864) (indictment in the military commission trial of Simeon B. Kight charged that defendant was “a guerrilla, and has been engaged in an unwarrantable and barbarous system of warfare against citizens and soldiers of the United States“); G. C. M. O. No. 93, pp. 3^ (1864) (indictment in the military commission trial of Francis H. Norvel charged “[b]eing a guerrilla” and specified that he “unlawfully and by his own wrong, [took] up arms as an outlaw, guerrilla, and bushwhacker, against the lawfully constituted authorities of the United States government“); id., at 9 (indictment in the military commission trial of James A. Powell charged “[trans-gression of the laws and customs of war'’ and specified that he “[took] up arms in insurrection as a military insurgent, and did join himself to and, in arms, consort with … a rebel enemy of the United States, and the leader of a band of insurgents and armed rebels“); id., at 10-11 (indictment in the military commission trial of Joseph Overstreet charged “[b]eing a guerrilla” and specified that he “did join, belong to, consort and co-operate with a band of guerrillas, insurgents, outlaws, and public robbers“).

10 Even if the plurality were correct that a membership offense must be accompanied by allegations that the “defendant ‘took up arms,’ “ ante, at 37, n.32, that requirement has easily been satisfied here. Not only has Hamdan been charged with providing assistance to top al Qaeda leadership (itself an offense triable by military commission), he has also been charged with receiving weapons training at an al Qaeda camp. App. to Pet. for Cert. 66a-67a.

11 The plurality recounts the respective claims of the parties in Quirin pertaining to this issue and cites the United States Reports. Ante, at 41-42. But the claims of the parties are not included in the opinion of the Court, but rather in the sections of the Reports entitled “Argument for Petitioners,” and “Argument for Respondent.” See 317 U. S., at 6-17.

12 The plurality concludes that military commission jurisdiction was appropriate in the case of the Lincoln conspirators because they were charged with ‘’ ‘maliciously, unlawfully, and traitorously murdering the said Abraham Lincoln,’ “ ante, at 40, n. 35. But the sole charge filed in that case alleged conspiracy, and the allegations pertaining to “maliciously, unlawfully, and traitorously murdering the said Abraham Lincoln” were not charged or labeled as separate offenses, but rather as overt acts “in pursuance of and in prosecuting said malicious, unlawful, and traitorous conspiracy. “ G. C. M. O. No. 356, at (emphasis added). While the plurality contends the murder of President Lincoln was charged as a distinct separate offense, the foregoing quoted language of the charging document unequivocally establishes otherwise. Moreover, though I agree that the allegations pertaining to these overt acts provided an independent basis for the military commission's jurisdiction in that case, that merely confirms the propriety of examining all the acts alleged—whether or not they are labeled as separate offenses—to determine if a defendant has been charged with a violation of the law of war. As I have already explained, Hamdan has been charged with violating the law of war not only by participating in a conspiracy to violate the law of war, but also by joining a war criminal enterprise and by supplying provisions and assistance to that enterprise's top leadership.

13 The plurality's attempt to undermine the significance of these cases is unpersuasive. The plurality suggests the Wirz case is not relevant because the specification supporting his conspiracy charge alleged that he “personally committed a number of atrocities.” Ante, at 45. But this does not establish that conspiracy to violate the laws of war, the very crime with which Wirz was charged, is not itself a violation of the law of war. Rather, at best, it establishes that in addition to conspiracy Wirz violated the laws of war by committing various atrocities, just as Hamdan violated the laws of war not only by conspiring to do so, but also by joining al Qaeda and providing provisions and services to its top leadership. Moreover, the fact that Wirz was charged with overt acts that are more severe than the overt acts with which Hamdan has been charged does not establish that conspiracy is not an offense cognizable before military commission; rather it merely establishes that Wirz's offenses may have been comparably worse than Hamdan's offenses.The plurality's claim that the charge against Lenger Grenfel supports its compound offense theory is similarly unsupportable. The plurality does not, and cannot, dispute that Grenfel was charged with conspiring to violate the laws of war by releasing rebel prisoners—a charge that bears no relation to a crime “ordinarily triable in civilian courts.” Ante, at 46, n. 37. Tellingly, the plurality does not reference or discuss this charge, but instead refers to the conclusion of Judge Advocate Holt that Grenfel also “ ‘united himself with traitors and malefactors for the overthrow of our Republic in the interest of slavery.’ “ Ibid, (quoting H. R. Doc. No. 314, at 689). But Judge Advocate Holt's observation provides no support for the plurality's conclusion, as it does not discuss the charges that sustained military commission jurisdiction, much less suggest that such charges were not violations of the law of war.

14 The plurality contends that international practice—including the practice of the IMT at Nuremberg—supports its conclusion that conspiracy is not an offense triable by military commission because “ ‘[t]he Anglo-American concept of conspiracy was not part of European legal systems and arguably not an element of the internationally recognized laws of war.’ “ Ante, at 47 (quoting T. Taylor, Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir 36 (1992)). But while the IMT did not criminalize all conspiracies to violate the law of war, it did criminalize “participation in a common plan or conspiracy” to wage aggressive war. See 1 Trials, pp. XI-XII. Moreover, the World War II military tribunals of several European nations recognized conspiracy to violate the laws of war as an offense triable before military commissions. See 15 U. N. Commission 90-91 (noting that the French Military Tribunal at Marseilles found Henri Georges Stadelhofer ‘ ‘guilty of the crime of association de malfaiteurs,” namely of “having formed with various members of the German Gestapo an association with the aim of preparing or committing crimes against persons or property, without justification under the laws and usages of war“); 11 id., at 98 (noting that the Netherlands’ military tribunals were authorized to try conspiracy to violate the laws of war). Thus, the European legal systems’ approach to domestic conspiracy law has not prevented European nations from recognizing conspiracy offenses as violations of the law of war. This is unsurprising, as the law of war is derived not from domestic law but from the wartime practices of civilized nations, including the United States, which has consistently recognized that conspiracy to violate the laws of war is an offense triable by military commission.

15 Though it does not constitute a basis for any holding of the Court, the Court maintains that, as a “general rule,” “the procedures governing trials by military commission historically have been the same as those governing courts-martial.“Ante, at 54, 53. While it is undoubtedly true that military commissions have invariably employed most of the procedures employed by courts-martial, that is not a requirement. See Winthrop 841 (“[Military commissions … are commonly conducted according to the rules and forms governing courts-martial. These war-courts are indeed more summary in their action than are the courts held under the Articles of war, and … their proceedings … will not be rendered illegal by the omission of details required upon trials by courts-martial'’ (emphasis in original; footnotes omitted)); 1 U. N. Commission 116-117 (“The [World War II] Mediterranean Regulations (No. 8) provide that Military Commissions shall conduc their proceedings as may be deemed necessary for full and fair trial, having regard for, but not being bound by, the rules of procedure prescribed for General Courts Martial” (emphasis added)); id., at 117 (“In the [World Warll] European directive it is stated … that Military Commissions shallhave power to make, as occasion requires, such rules for the conduct of their proceedings consistent with the powers of such Commissions, and with the rules of procedure … as are deemed necessary for a full and fair trial of the accused, having regard for, without being bound by, the rules of procedure and evidence prescribed for General Courts Martial“). Moreover, such a requirement would conflict with the settled understanding of the flexible and responsive nature of military commissions and the President's wartime authority to employ such tribunals as he sees fit. See Birkhimer 537-538 (“[Military commissions may so vary their procedure as to adapt it to any situation, and may extend their powers to any necessary degree…. The military commander decides upon the character of the military tribunal which is suited to the occasion … and his decision is final“).

16 The Court suggests that Congress’ amendment to Article 2 of the UCMJ, providing that the UCMJ applies to “persons within an area leased by or otherwise reserved or acquired for the use of the United States,” 10 U. S. C. §802(a)(12), deprives Yamashita's conclusion respecting the President's authority to promulgate military commission procedures of its “precedential value.” Ante, at 56. But this merely begs the question of the scope and content of the remaining provisions of the UCMJ. Nothing in the additions to Article 2, or any other provision of the UCMJ, suggests that Congress has disturbed this Court's unequivocal interpretation of Article 21 as preserving the common-law status of military commissions and the corresponding authority of the President to set their procedures pursuant to his commander-in-chief powers. See Quirin, 317 U. S., at 28; Yamashita, 327 U. S., at 20; Madsen v. Kinsella, 343 U. S. 341, 355 (1952).

17 It bears noting that while the Court does not hesitate to cite legislative history that supports its view of certain statutory provisions, see ante, at 14^15, and n. 10, it makes no citation of the legislative history pertaining to Article 36(b), which contradicts its interpretation of that provision. Indeed, if it were authoritative, the only legislative history relating to Article 36(b) would confirm the obvious—Article 36(b)'s uniformity requirement pertains to uniformity between the three branches of the Armed Forces, and no more. When that subsection was introduced as an amendment to Article 36, its author explained that it would leave the three branches “enough leeway to provide a different provision where it is absolutely necessary” because “there are some differences in the services.” Hearings on H. R. 2498 before the Subcommittee No. 1 of the House Committee on Armed Services, 81st Cong., 1st Sess., 1015 (1949). A further statement explained that “there might be some slight differences that would pertain as to the Navy in contrast to the Army, but at least [Article 36(b)] is an expression of the congressional intent that we want it to be as uniform as possible.” Ibid.

18 In addition to being foreclosed by the text of the provision, the Court's suggestion that 10 U. S. C. A. §839(c) (Supp. 2006) applies to military commissions is untenable because it would require, in military commission proceedings, that the accused be present when the members of the commission voted on his guilt or innocence.

19 The Court does not dispute the conclusion that Common Article 3 cannot be violated unless and until Hamdan is convicted and sentenced. Instead, it contends that’ ‘the Geneva Conventions d[o] not direct an accused to wait until sentence is imposed to challenge the legality of the tribunal that is to try him.” Ante, at 62, n. 55. But the Geneva Contentions do not direct defendants to enforce their rights through litigation, but through the Conventions’ exclusive diplomatic enforcement provisions. Moreover, neither the Court's observation respecting the Geneva Conventions nor its reference to the equitable doctrine of abstention bears on the constitutional prohibition on adjudicating unripe claims.

20 Notably, a prosecutor before the Quirin military commission has described these procedures as “a substantial improvement over those in effect during World War II,” further observing that “[t]hey go a long way toward assuring that the trials will be full and fair.” National Institute of Military Justice, Procedures for Trials by Military Commissions of Certain Non-United States Citizens in the War Against Terrorism, p. x (2002) (hereinafter Procedures for Trials) (foreword by Lloyd N. Cutler).

1 Section 821 looks to the “law of war,” not separation of powers issues. And §836, as Justice Kennedy notes, concerns procedures, not structure, see ante, at 10.