Article contents

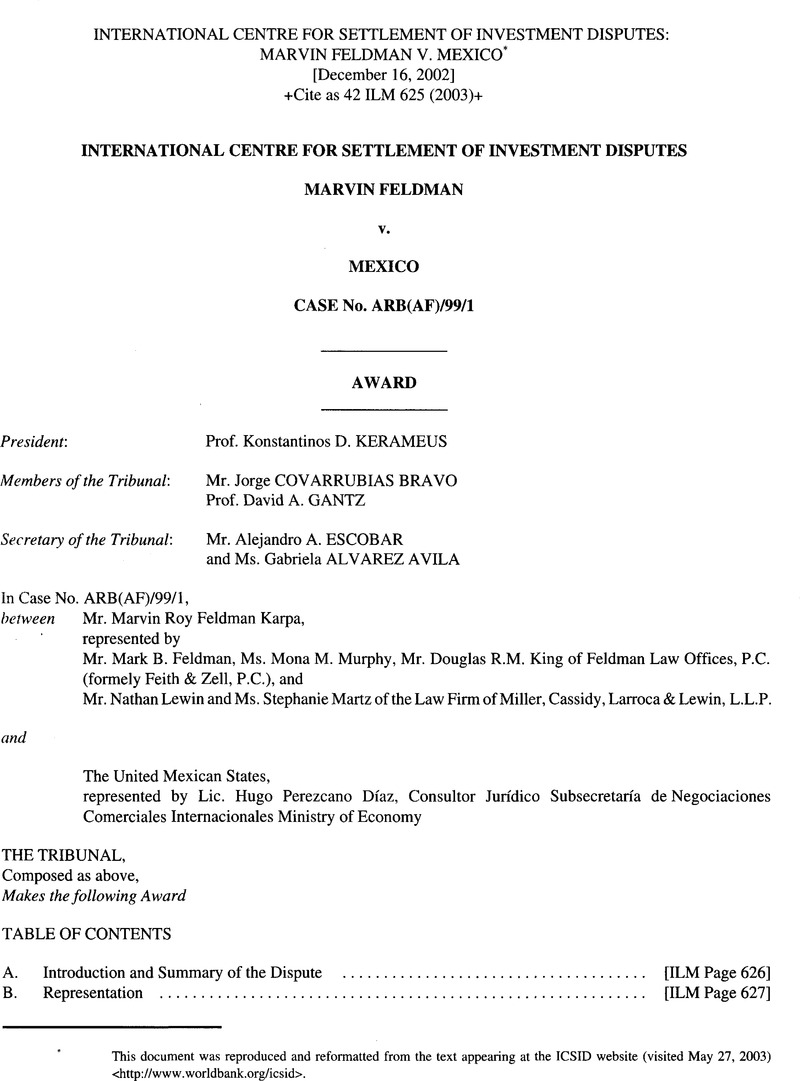

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes: Marvin Feldman v. Mexico*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 July 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2003

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the ICSID website (visited May 27, 2003) <http://www.worldbank.org/icsid>.

References

Endnotes

page 670 note 1 See the Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim, submitted under NAFTA Article 1119, p. 2. The Notice of Intent also mentioned NAFTA Article 1106, on performance requirements, but the obligations of this provision were not invoked in the Notice of Claim.

page 670 note 2 Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States, opened for signature March 18, 1965, entered into force October 14, 1966.

page 670 note 3 The Claimant's Notice of Arbitration, p. 5 (submitted on April 30, 1999).

page 670 note 4 The Claimant subsequently submitted an additional request for a declaration that Mexico had breached its obligations to afford CEMSA national treatment under NAFTA Article 1102.

page 670 note 5 Emphasis added. Paras. 2-6 provide for compensation “equivalent to the fair market value of the expropriated investment immediately before the expropriation took place;” that compensation be paid without delay and be fully realizable; include interest in a hard currency; and be freely transferable. Id. Article 1110(1) (2-6).

page 670 note 6 Memorial, paras. 151 ff.; counter-memorial, paras. 335 ff. (with some qualifications). It is important to note that the language used by the Restatement, section 712, differs significantly from that used in NAFTA, even though the concepts are similar.

page 670 note 7 The Tribunal notes that the S.D. Myers tribunal (citing Pope&Talbot) effectively concluded that the words “tantamount to expropriation” were designed to embrace the concept of “creeping” expropriation rather than to “expand the internationally accepted scope of the term expropriation.” See S.D. Myers v. Government of Canada Partial Award, November 13, 2000, para. 286, <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/3992.pdf>.

page 670 note 8 As discussed in the “Damages” section of this Award (paras. 189-207), there is a serious question as to whether the Claimant's business would have been economically viable even had SHCP consistently granted the rebates in the proper amount, given the very low gross profit, based on the gross profit of less than US$0.10 between CEMS A's net-of-tax cost of the cigarettes and the selling prices realized from CEMSA's customers.

page 670 note 9 First, NAFTA Article 2103 generally excludes tax measures from coverage under NAFTA: “Except as set out in this Article, nothing in this Agreement shall apply to tax measures.” However, this exclusion is not absolute. Article 21O3(3)(b) makes Article 1102 applicable to tax measures, and Article 2103(6) makes Article 1110 applicable under certain conditions. Article 1105 is not mentioned among the exceptions to the exclusion; therefore, it does not apply to tax measures, other than in a situation in which an expropriation under Article 1110 has been found, and there is an analysis as to whether the expropriatory action met the requirements of due process and Article 1105 as provided in Article 1110(l)(c).

page 670 note 10 Pope&Talbot v. Government of Canada Interim Award, June 26,2000, paras. 87-88, <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/3989.pdf>. Canada also asserted that “tantamount” simply means “equivalent,” and that this language was not intended to expand Article 1110's coverage beyond creeping expropriation to cover regulatory action. Id. para. 89.

page 670 note 11 Also, although the Tribunal is aware, as indicated earlier, that the 1999 Fiscal Court proceedings challenging SHCP's efforts to recoup tax rebates from the Claimant are not final, the most recent decision has upheld the Claimant's position that the requirements of the IEPS law for invoices stating the tax amounts separately and precluding rebates for exports to low tax jurisdictions, are unconstitutional under Mexican law. The significance of this court decision is somewhat offset by the fact that in a separate, 1998 proceeding challenging denials of tax rebates from October 1997 through January 1998, which is final, another Mexican court determining essentially the same issues found in favor of SHCPsee Amparo decision of August 24, 2000).

page 671 note 12 See, e.g. Annex 6 of the Claimant's reply memorial, providing copies of recent newspaper reports regarding the smuggling of U.S. cigarettes to Canada and several European countries; indications that cigarette producers in Mexico have reduced cigarette prices by 25% in order to compete more effectively with smuggled cigarettes (transcript, July 12, 2001, p. 148); and documentation provided by the Respondent suggesting that some cigarettes exported from Mexico to the United States are being re-imported into Mexico from El Paso.

page 671 note 13 Technically, the Amparo appears to apply only to the IEPS law challenged, i.e. the 1990 version. However, Article 2(111) of the law was further amended in 1992 to provide the 0% tax rate to reseller/exporters as well as producer/exporters, so long as the destination nation was not a low tax (tax haven) jurisdiction.

page 671 note 14 Although the tax base for the IEPS cigarette tax was the retail sale price, under the IEPS law the party responsible for paying the tax was the producer or its controlled distributor, not the retailer, presumably to assure that the full amount of the taxes would be paid in a distribution system where many of the retailers were small kiosk operators who apparently were not trusted to remit the proper tax amounts to SHCP, or to maintain records adequate to assure SHCP that the full taxes were being paid. See IEPS Law, Article 11 (1991).

page 671 note 15 The record is largely devoid of any statement of CEMSA's physical assets. The Claimant asserts that the initial capitalization of CEMSA upon its formation in 1998 was a total of $ 510,000 Mexican pesos, but there is no indication as to what percentage of this was paid in capital. Feldman declaration of March 28, 2001, para. 1. Moreover, the Claimant's claim for compensation is based almost entirely on a calculation of lost profits and its value as a going business [concern], plus a demand for the rebates anticipated but not paid for October-November 1997. See memorial, para. 231.

page 671 note 16 Several possible reasons emerged during the hearing. It was suggested that Article 4 of the IEPS law could only have been challenged within 15 days of the enactment of the provision, which occurred in 1984 or 1985, well before CEMSA was incorporated, or tbecause at the time the Article 4 requirements had not been applied to the Claimant (transcript, July 12, 2001, pp. 127-135, testimony of Oscar Enriquez Enriquez).

page 671 note 17 The IEPS applied to alcoholic beverages appears to function in a manner similar to normal value added taxes, with each succeeding seller being treated as a taxpayer. The special rules using the retail price as the tax base but making the producer or distributor the person responsible for paying the taxes for cigarettes apparently apply only to tobacco products, gasoline and diesel fuel. See IEPS law, Article 11 (1992 and other years).

page 671 note 18 It states in operative part that “you are hereby confirmed your opinion in the sense that you are entitled to request the return of the balance in your favor resulting from the crediting of the special tax on production and services paid on the acquisition of alcoholic beverages and processed tobacco exported as from January 1 st, 1992, provided such exports are made to countries with an Income Tax rate applicable to legal entities exceeding 30%.” (Letter from Jose Antonio Riquer Ramos to CEMSA, March 12,1992, App. 0062- 0069.) SHCP reserved the rights of surveillance and verification. It is also unfortunate that neither the Claimant nor the Respondent were able to produce a copy of the February 6, 1992, letter to which SHCP's letter was a response, so it is impossible for the Tribunal to know whether this response was in the context of a letter raising the Article 4 invoice issue, or, equally likely, raising only the 0% tax rate issue which was then before the Supreme Court.

page 671 note 19 As discussed more fully in the section of this award on discrimination, evidence in the record suggests that there are 5-10 or more firms registered under Mexican law as cigarette exporters. (Obregon-Castellanos testimony, transcript, July 9, 2001, p. 141). It may well be that the requirements of Article 4 have been waived from time to time for them as well given the practical impossibility for resellers to export without the tax rebates, although the Mexican government has unfortunately been unwilling or unable to enlighten the Tribunal on this fact.

page 671 note 20 Using the formula 7.40 = 1.85 X, where X is the price net of tax, X = 7.40/1.85 = 4.00. (See Feldman affidavit, Mar. 28, 2001, para. 6.) The remaining amount is the tax, US$7.40-US$4.00 = US$3.40. See IEPS law, Article 2(1 )(H).

page 671 note 21 Although the methodology used in 1996 is relatively obscure (see Zaga-Hadid affidavit, annex A, exh. 3 of memorial), the result of the methodology used was to increase the portion of the purchase price treated as IEPS taxes subject to rebates from 45.95% to 55.95% of the purchase price.

page 671 note 22 He arrived at this figure by simply multiplying the price of US$7.40 by 85%, in other words, treating 85% of the purchase price as tax amounts subject to government rebate upon exportation. (Zaga-Hadid affidavit, annex 3; first Feldman statement, para. 70.) This increased the tax amounts, in an unwarranted way, from 45.95% to 85% of the gross sales price.

page 671 note 23 There was considerable discussion in the testimony of the parties regarding whether one of the Poblano Group companies, Lynx, had received excess IEPS rebates for 1991 as a result of Lynx's Amparo suit. (See third statement of Enrique Diaz Guzman, paras. 7-8, App. 6455-6456; declaration of Oscar Enriquez Enriquez, Jun. 8, 1991, paras. 3bis 14Z/s.) However, the Tribunal believes that the Claimant failed to demonstrate that the amounts received on behalf of Lynx were excessive, once interest and an inflation factor for the five year period between accrual and payment are factored in.

page 672 note 24 Respondent made an extensive effort in its briefs and during the hearing to document a series of export transactions by the Claimant, and to link those exports with re-entry of the cigarettes into Mexico. While Respondent was unable to demonstrate that the Claimant was aware of any such illegal practices, or that any of the cigarettes the Claimant exported were re-entered into Mexico, Respondent did demonstrate evidence of a serious problem. Counter-memorial, pp. 104-116, and transcript, July 12, 2001, pp. 148 ff.

page 672 note 25 See supra paras. 130, 131, and Respondent's exhibits for cross-examination of the Claimant, Vol. II, tab 6.

page 672 note 26 Moreover, under international law, there is considerable doubt whether the discrimination provision of Article 1110 covers discrimination other than that between nationals and foreign investors, i.e. it is not applicable to discrimination among different classes of investors, such as between producers and resellers of tobacco products, at least unless all producers are nationals and all resellers are aliens. Thus, under the Restatement, the relevant comment states that “a program of taking that singles out aliens generally, or aliens of a particular nationality, or particular aliens, would violate international law.” The comment does not refer to discrimination between national producers and resellers (whether national or foreign) operating under somewhat different circumstances, particularly under the tax laws. Also, there is an implication in the NAFTA Parties’ interpretation of Article 1105 of July 31, 2001, that a breach of one substantive provision of Section A should not in itself be considered a breach of a separate provision (NAFTA Free Trade Commission, Notes of Interpretation of Certain Chapter 11 Provisions, July 31, 2001, consulted on the web site of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade of the Government of Canada. See NAFTA Articles 1131(2) and 2001).

page 672 note 27 Moreover, the Mexican courts have been deciding issues of national law which it is inappropriate for the Tribunal to review, except and unless those determinations (or of Mexican administrative agencies such as SHCP) are themselves denials of justice or otherwise in violation of NAFTA or international law.

page 672 note 28 See Metalclad Corporation v. United Mexican States Award, August 30, 2000, paras. 1, 32,38,40,45-46, 16 ICSID Review. FILJ 1, 2001. Metalclad and Mexican federal environmental authorities entered into an agreement in which Metalclad agreed, interalia to make certain modifications in the site, take specified conservation steps, recognize the participation of a Technical Scientific Committee and a Citizen Supervision Committee, employ local manual labor, and make regular contributions toward the social welfare of the municipality, including limited free medical advice. Id. para. 48.

page 672 note 29 This is rather strangely characterized as an act “tantamount to expropriation,” although it probably was more accurately described as a direct expropriation. Id. paras. 109-111. Ultimately, the tribunal awarded Metalclad compensation of US$16,685,000 for the loss of its investment in Mexico (more than US$90 million in damages was sought) based on violations of NAFTA Articles 1105 (fair and equitable treatment) and 1110 (expropriation). See Metalclad, Id., paras. 76-92, 103-105, 123-125, 128, 131.

page 672 note 30 Here, as in Metalclad there was without doubt a lack of transparency with regard to some actions by Mexican government officials. Yet, if the British Columbia Supreme Court is correct that lack of transparency is not in itself a violation of Chapter 11 of NAFTA, the fact that SHCP communications and other actions after the 1993 Amparo decision were inconsistent and ambiguous, and difficult for the Claimant to assess, are insufficient to justify a finding of expropriation under Article 1110.

page 672 note 31 S.D. Myers v. Government of Canada Partial Award, November 13, 2000, para. 280, <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/3992.pdf>.

page 672 note 32 The Claimant had argued that the Canadian lumber export control regime had “deprived the Investment of its ordinary ability to alienate its product to its traditional and natural market,” and that by reducing the claimant's quota of lumber that could be exported to the United States without paying a fee, Canada violated Article 1110. Pope&Talbot v. Government of Canada Interim Award, June 26, 2000, para. 81, <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/3989.pdf>.

page 672 note 33 For a discussion of the profitability of the Claimant's cigarette exporting business (or lack thereof), see Section J, infra.

page 672 note 34 Mexico has provided excerpts from United States submissions in other cases, which imply that there must be a showing that the reason for differential treatment is nationality. See, e.g. U.S.Submission of April 7,2000, in Pope & Talbot <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/4097.pdf>. However, such statements were made in the context of cases with different fact situations and, possibly, legal and policy considerations. Under those circumstances, this Tribunal chooses not to consider them.

page 672 note 35 See Daniel M. Price & P. Brian Christy, An Overview of the NAFTA Investment Chapter, in The North American Free Trade Agreement: A New Frontier in International Trade and Investment in the Americas 165, 174 (Judith H. Bello, Allan F. Holmer&Joseph J. Norton, eds., 1994).

page 672 note 36 The issue of whether the size of the “universe” of foreign investors, and of domestic investors, matters has been an issue in other NAFTA Chapter 11 cases, including S.D. Myers ﹛see S.D. Myers v. Government of Canada Partial Award, November 13, 2000, paras. 93,112,256,)and particularly in Pope&Talbot ﹛see Pope&Talbot v. Government of Canada Interim Award, June 26,2000, paras. 11, 24, 36, 38, <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/3989.pdf >). However, the Respondent here has not raised that issue, and the Tribunal accordingly does not address it ﹛see infra paras. 185, 186).

page 673 note 37 With minor exceptions, NAFTA does not regulate the creation and maintenance of monopolies. "Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent a Party from designating a monopoly." Article 1502(1). Thus, affording cigarette producers a monopoly on exports would not appear to be an article 1102 violation, as long as all non-producers, both domestic and foreign, are treated in the same manner.

page 673 note 38 United States –Measures Affecting Imports of Woven Wool Shirts and Blouses from India, Adopted 23 May 1997, WT/DS33/AB/R, p. 14. Accordingly, Asian Agricultural Products Limited v. Republic of Sri Lanka, ICSID Reports, pp. 246, 272,1990. ("In case a party adduces some evidence which prima facie supports his allegation, the burden of proof shifts to his opponent.").

page 673 note 39 Counter-memorial, para. 488; see, e.g., transcript, July 10, 2001, pp. 110-113. It is undeniable that CEMSA and the Poblano Group maintained a business relationship; CEMSA, inter alia, was a seller of cigarettes to several of the Poblano Group companies from time to time, and had borrowed working capital from Mr. Poblano (memorial, paras. 101-102). However, there is no evidence of any common stock ownership, common membership on corporate boards of directors or any of the normal indices of common ownership and control. Moreover, SHCP has treated the two as completely separate taxpayers, audited CEMSA early on, while more than three years later no final action has been taken against the Poblano Group. Clearly, there is no evidence that the Mexican government considered CEMSA and the Poblano Group companies to be a common enterprise prior to this proceeding. Accordingly, this Tribunal would not be inclined to treat them as such so as to defeat the Claimant's assertion of discrimination.

page 673 note 40 See Zaga-Hadid testimony, transcript, July 13, 2001, p. 142, tables introduced into evidence during the hearing. Allegations that Lynx had been intentionally paid excessive rebates by SHCP were denied (third witness statement of Diaz-Guzman, App. 06455-06456) and further disputed at the hearing by both parties. The evidence on this issue before the Tribunal is conflicting, and the Tribunal is not convinced that the amounts paid, including interest paid and the inflation adjustment for the 1993-1996 period, were in fact excessive.

page 673 note 41 We observe, without deciding, that even if there had been an expropriation, there is inadequate proof in the record to demonstrate that CEMSA had more than negligible going concern value. As noted in footnote 15, there is no statement of CEMSA's physical assets in the record, other than an assertion of an initial capitalization of 510,000 Mexican pesos at the time of formation in 1988, without any indication as to what percentage of this was paid in. The going concern value of an enterprise which earns 90% of its alleged revenues from gray market sales of cigarettes is also suspect. As discussed in para. 201, infra, after selling and financing costs, this operation could not have been profitable, and a money losing business seldom has significant value as a going concern.

page 681 note 1 See Section H3.3 of the Award, paragraphs 117 y 188.

page 681 note 2 See Section H3.4, paragraph 136.

page 681 note 3 See Jaime Zaga Hadid's Affidavit, where he states the following “I know that the cigarette business was by far CEMSA's most profitable business line. By 1997, cigarette exports represented more than 90% of CEMSA's gross profits.“

page 681 note 4 1991-1998 Tax Resolutions, Volume 1 Audits, 1996 and 1997 bank statements of account, 1996 and 1997 checks’ supporting documents, 1996 and 1997 purchase invoices, 1996 and 1997 journal and earnings supporting documents, 1996 and 1997 Journal Reports, Financial Information, 1996 and 1997 Export Documentation.

page 681 note 5 Claimant's Statement.

page 681 note 6 Article 22 of the Federation's Fiscal Code.

page 681 note 7 The record shows that CEMSA obtained the following rebates: on May 15, 1996, $21,761; on June 4, 1996, $240,752; on October 12, 1996, $1,061,033; on July 10, 1996, $335,183; on September 9, 1996, $612,908, on October 18, 1996, $1,588,138; on December 2, 1996, $5,010,722; on January 20,1997, $12,908,447, on February 4,1997, $783,360; on March 4,1997, $9,173,115; on April 4,1997, $5,368,500; on May 6, 1997, $6,220,528; on June 4, 1997, $7,899,720; on July 3, 1997, $8,052,575; on September 10, 1997, $8,849,367; on August 5, 1997, $5,259,676 and on November 3, 1997, $9,032,364.

page 681 note 8 See note 25 of the Award and its references.

page 681 note 9 CEMSA stablishes at pages 54, paragraphs 128, 129 y 130 of English version and pages 59 and 60, paragraphs 128, 129 and 130 Spanish version as follows: “128. Around July, 1999, Claimant learned that Hacienda was permitting cigarette exports and making rebates of IEPS taxes on such exports to at least one company owned by Mexican citizens that, like CEMSA, is not a cigarette producer. That company was Mercados Regionales, S.A. de C.V. (“Mercados I“). This information CAME from Cesar Poblano, a principal in the LYNX business, who had also been a lender to CEMSA in 1997 when CEMSA borrowed to finance cigarette purchases as discussed above. Feldman Decl.) 91. 129. Later, Claimant obtained documents showing Hacienda's payment of IEPS rebates to Mercados I for cigarette exports made in 1999. He received these documents from CEMSA's former counsel, Javier Moreno Padilla. Feldman Decl.) 91; and see documents at App. 0473-0505. 130. CEMSA's complaints to the Tribunal about this discrimination apparently disrupted Mercados I's arrangements with Hacienda, and its owners made efforts to substitute a new corporation as the exporter of record, Mercados Extranjeros, S.A. de C.V. (“Mercados II“). These efforts failed, at least temporarily, because Hacienda mistakenly believed that Marvin Feldman was involved in Mercados II's business. Feldman Decl.) 92; App. 0470-72.“

page 681 note 10 To the same effect, Giuseppe Chiovenda. Istituzioni de Diritto Processuale Civile Vol. Ill, p 99.

page 681 note 11 See M. Feldman Statement, paragraphs 72 and 73, where he acknowledges having borrowed money from Mr. Poblano to purchase cigarettes, with a 14% interest on the loan that was to be returned after obtaining the IEPS rebate; it is clear that they had an agreement to share in the profits and not only an arrangement for the payment of interest.

page 682 note 12 For instance, the United States of America and Canada, who are Mexico's trade partners in the NAFTA, are also bound to keep the information on their taxpayers confidential. So much so that both countries have entered into a broad Tax Information Exchange Agreement with Mexico to exchange data pertaining to their taxpayers, but undertaking to ensure that the information received from one another will be handled with the same degree of confidentiality as that obtained on the basis of their domestic law. On the matter of the banking secret, attorney-client privilege and the confidentiality of returns and information obtained by the tax authorities, in Spain, Germany and Argentina, see Guiliani Fonrouge, Derecho Financiero, Vol. 1, p. 549, Ediciones Depalma, Buenos Aires, 2001.

page 682 note 13 From official letter no. DGCJN.J11.01.373.01 dated July 2, 2001 can be read: ”… With respect to files 328 and 333, as has been manifested by the Respondent, these are files that contain confidential information from third party taxpayers, the disclosure of which is forbidden by Law. The Respondent advised the Tribunal on the restriction in the matter of providing confidential taxpayer information through its official letter of January 11, 2001. Neither the person signing this official letter, nor any official from the Ministry of the Economy or their consultants have access to these files, nor have they had any and we are not authorized to know their content. Respectfully, the Respondent does not have knowledge according to which rules the Tribunal could authorize the officials from the Ministry of the Economy or other persons to have access to such communications. Moreover, any official from the Ministry of the Treasury and Public Credit that divulges information contained in the referred to files can incur in administrative and criminal liability … The order of the Tribunal would obligate the officials from the Ministry of the Treasury and Public Credit to act in direct contravention of precise legal dispositions and would personally make them incur in the risk of responsibility.“

page 682 note 14 Same official letter as that cited in the last part.

page 682 note 15 Equal circumstances, according to the comments on article 24. Nondiscrimination of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development's Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital, arise when de jure and de facto conditions are similar. The United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention between Developed and Developing Countries has provisions to the same effect. The evidence furnished by the Claimant does not meet those requirements.

page 682 note 16 Comment 2 to Article 15 of that Agreement states the following: “Composite acts covered by Article 15 are limited to breaches of obligations which concern some aggregate of conduct and not individual acts as such. In other words, their focus is a series of acts or omissions defined in aggregate as wrongful. Examples include the obligations concerning genocide, apartheid or crimes against humanity, systematic acts of racial discrimination, systematic acts of discrimination prohibited by a trade agreement, etc

- 2

- Cited by