To the Editor—Collaborative public health partnerships between competing healthcare system hospitals are uncommon in today’s healthcare environment, despite their potential for improving community health.Reference Prybil, Scutchfield and Dixon 1 – Reference Ainsworth, Diaz and Schmidtlein 4 One potential area of collaboration between hospital systems is management of influenza season parameters and messaging team members and the community. Traditionally, acute-care facilities make independent decisions regarding influenza season parameters. In geographic areas with multiple healthcare systems, the lack of coordination in influenza-season decision making can lead to a local patchwork of policies and messages. These different public health messages can be confusing to patients and the public, potentially affecting patient care, visitor access, and patient satisfaction.

We established a regional collaboration between multiple healthcare systems that emphasized information sharing and unified messaging to the public and local media. A weekly conference call was initiated that included 6 competing healthcare entities located in the piedmont region of North Carolina: Novant Health, Cone Health, Randolph Health, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Atrium Health, and High Point Regional UNC Health Care. In total, these systems represent 36 acute-care facilities covering ∼9,000 square miles with ∼4 million people. 5 All of these systems have mandatory influenza vaccination programs for team members, and 4 of the systems have mandatory masking programs for team members unable to be vaccinated (ie, Novant Health, Atrium Health, High Point Regional UNC Health Care, and Randolph Health). The call included infection prevention representatives, marketing/communication professionals, nursing leaders, physicians, and hospital administrators. Each healthcare system reported their local emergency department influenza-like-illness (ILI) rate for comparison with the other systems. Facility differences were noted based on the geographic location of the hospitals. Emergency department (ED) ILI data were obtained using the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool (NC DETECT), a statewide syndromic surveillance system. 6 Collective decisions were made to establish parameters for influenza season, which were then communicated through internal and external communication pathways.

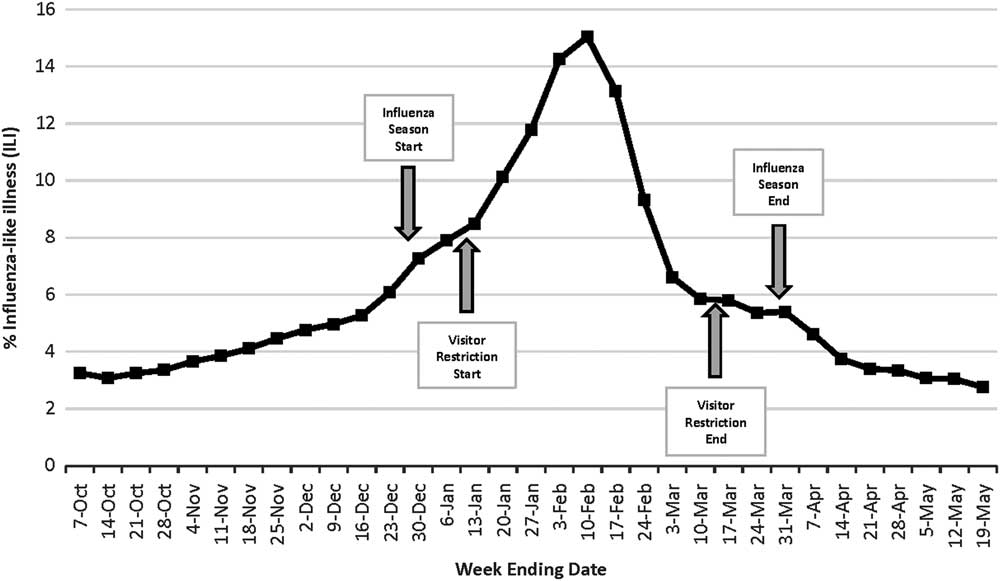

Influenza season was declared when the ILI rate in North Carolina hospital ED visits reached ≥5% and ended when the ILI rate declined back to <5% (Fig. 1), considering the general ILI trend. For the 2017–2018 influenza season, the start date was December 27, 2017, and the end date was March 30, 2018. Declaring when influenza season started and ended was more important for those healthcare systems that require mandatory masking of team members who do not receive an influenza vaccination, as this was the date in which mandatory masking began. In the past, for some healthcare systems, the influenza season started and ended using predetermined dates such as October 1 (start) and March 31 (end). Although the time between these predetermined dates typically encompassed the influenza season, these dates did not consider variations in influenza activity in a given year. Using predetermined influenza season dates instead of a data-based approach has the potential to lead to team member masking early in the season when it might not be necessary or to the discontinuation of masking later when influenza activity remains high. Our approach allowed for masking only during times of true increased influenza activity and allowed for extension of the traditional influenza season if warranted.

Fig. 1 Influenza-like illness surveillance, North Carolina Emergency Departments, 2017–2018. Near real-time syndromic surveillance for ILI is conducted through the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool (NC DETECT). This system uses a variety of data sources including emergency departments (EDs). NC DETECT is currently receiving data daily from 126 of the 126 24/7 emergency departments in North Carolina. The NC DETECT ILI syndrome case definition includes any case with the term “flu” or “influenza,” or at least 1 fever term and 1 influenza-related symptom.

Visitor restrictions, defined as the restriction of visitation to an acute-care facility by children <13 years of age, was instituted by all healthcare systems when the ILI rate was ≥7% and lifted when the ILI rate returned to <7% (Fig. 1). For the 2017–2018 influenza season, visitor restrictions were initiated on January 12, 2018, and lifted on March 16, 2018. When the ≥7% threshold was reached, a coordinated effort was made between the healthcare systems to provide consistent messaging to team members and the media about who would be restricted from acute-care facilities and when. This was particularly effective for communicating with local media outlets as the media reported the collective decision using a single story. 7 , 8 In years past, multiple media stories would have been published as each system made their decision, leading to mixed public messaging. Likewise, when the level of influenza activity fell to <7%, the media was informed that visitor restrictions would be lifted. We found that marketing and communication professionals were vital to the success of this process.

One additional benefit was noted. In our communities, team members often work in multiple facilities moving between the different healthcare systems. A unified approach to the influenza season reduced confusion when team members moved between hospitals.

Our approach has some limitations. The chosen thresholds for our decisions were based on clinical judgement and not published research. In addition, the size of some of the healthcare organizations meant that a few hospitals were geographically distant. Thus, the ILI rate near those facilities might vary significantly from the other facilities in the collaborative. This distance has led to the consideration of developing additional collaboratives in those areas.

The development of this process was a simple solution that improved communication between competing healthcare systems, simplified public messaging around influenza season, and standardized influenza season parameters in a single geographic region. The collaboration and exchange of information also increased the congeniality between the healthcare systems, and the participants found it to be informative and enjoyable. We hope that we can apply this approach to additional issues to benefit the communities that we serve.

Acknowledgments

The case data used in this study were provided by the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool (NC DETECT), an advanced, statewide public health surveillance system. NC DETECT is funded with federal funds by North Carolina Division of Public Health (NC DPH), Public Health Emergency Preparedness Grant (PHEP), and is managed through a collaboration between NC DPH and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Emergency Medicine’s Carolina Center for Health Informatics (UNC CCHI).

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.