Since the 2000s, we have observed significant reforms of family policy in South Korea. Most notably, a series of improvements in subsidized childcare brought an era of free childcare for all. For families that do not want externally provided childcare, a home-care allowance is available, regardless of household income. The reforms translated into a six-fold increase in social expenditures on families, from 2 to 13 per cent of total social spending between 2002 and 2012, placing family policy expenditure as the third largest element of public spending, only below old-age and health care expenditures. Corresponding to the dramatic expenditure increase, Korea has experienced a huge leap in the percentage of children (under the age of two) in childcare during the same period – from 3.9 per cent (far below the OECD average) to 36.1 per cent (above the OECD average) (OECD 2016). The percentage of children in publicly funded childcare has also greatly increased, from 30.1 in 2004 to 62.1 in 2006, and to 98.9 in 2015 (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2015). Policy changes of such magnitude have important implications for the developmental/productivist model of social policy, which largely draws on the experience of East Asian welfare states (Holliday Reference Holliday2000; Kwon Reference Kwon2005; White and Goodman Reference White and Goodman1998). The model suggests a clear hierarchy in public policy; while economic policy was regarded as the highest priority, reflecting the late industrializers’ strong desire to catch up with advanced economies, social policy was relegated to be a ‘handmaiden’ of economic development. In order to maximize investment in industrialization, the government minimized public welfare expenditure, and the lion’s share of social policy was geared towards productive populations.

In the absence of a comprehensive social security system, the family was assumed to take a central role in welfare provision. As a result, welfare expenditure on the family was virtually non-existent. In the context of the developmental bias in public policy, recent family policy reforms, with their huge increases in the state’s financial commitments to the family, imply a fundamental change in the Korean welfare state. Moreover, the reforms have wider implications for developmentalism in East Asian social policy on the whole, owing to the prominence ascribed to Korea in the literature. Korea is often considered as a critical case for the understanding of the developmental model, having been portrayed as the case that most resembles the archetype of the model (Holliday Reference Holliday2000; Ringen et al. Reference Ringen, Kwon, Yi, Kim and Lee2011; Tang Reference Tang2000). Yet, family policy expansion occurred on a much larger scale in Korea than in Japan or Taiwan (An and Peng Reference An and Peng2016). Hence, an investigation of Korean family policy reforms enhances our understanding of the future of welfare developmentalism in East Asia.

This article aims to explain the political underpinnings of Korean family policy reforms by highlighting the critical role of political parties. Political parties have received scant attention in the literature on East Asian welfare states, and that is particularly the case with the literature on the Korean welfare state. The reason for this is two-fold. First, the developmental (welfare) state literature has been influential in understanding Korean and East Asian welfare politics (Deyo Reference Deyo1992; Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, White and Kwon1998; Kwon Reference Kwon2005). Portraying bureaucrats as the driver of welfare state development in Korea left little room to acknowledge the rise of new actors in social policymaking. Second, even when scholars broadened the scope of investigation beyond bureaucrats, the conventional wisdom – which sees Korean parties as non-policy-oriented parties – hindered the development of an account that captured the new roles parties have taken on in welfare politics. To fill this gap in the literature, this article investigates the role of political parties in family policy reforms. In doing so, it specifically asks the following research questions: how have political parties emerged as the driver of family policy reforms? And, why have supposedly non-policy-oriented parties moved family policy centre stage in election campaigns? The main argument of the article is that a generational change in the Korean electorate incentivized parties to pay greater attention to policy issues, and family policy was deemed instrumental to draw in young voters, especially young women, whose support has become increasingly important for electoral victory.

This article is structured as follows. The first part delineates the development of family policy and juxtaposes the modest and comprehensive nature of family policy before and after the reforms in the 2000s. The second part reviews the literature on Korean party politics in comparative perspective and shows, with reference to the wider comparative welfare state literature, that studies of the Korean welfare state have paid insufficient attention to political parties. The third part investigates how the Korean parties emerged as a key agency of family policy reforms and why they promoted family policy as one of the central issues of elections in the 2000s. Lastly, the article concludes by summarizing its findings. With reference to research methods, the research draws on quantitative evidence (various election survey data) as well as qualitative evidence (14 interviews with party officials and senior bureaucrats, party manifestos and government white papers). In terms of time frame, it covers three governments since the 2000s: the centre-left Roh Moo-Hyun government (2003–8) and the conservative Lee Myung-Bak and Park Geun-Hye governments (2008–13 and 2013–present, respectively).

THE DEVELOPMENT OF KOREAN FAMILY POLICY

Welfare Developmentalism and Family Policy before the 2000s

Much of the literature on East Asian welfare capitalism highlights the developmental bias in public policy in the region. It is postulated that the state had an entrenched interest in maximizing resources for economic development while minimizing public expenditure on social security programmes (Kwon Reference Kwon2005). Even residual social protection is geared towards ‘productive’ populations (notably, male workers of large enterprises and public sector employees), while ‘non-productive’ populations (such as women, children and the elderly) are not considered ‘worthy’ of state welfare efforts. The absence of a comprehensive welfare system puts a heavy burden on the family, in particular on women, to care for those in need, especially for the non-productive populations (Goodman and Peng Reference Goodman and Peng1996; Kwon Reference Kwon1997). It is imperative, therefore, that women perform the role of unpaid caregiver in order to maximize investment in economic development. This also explains why other key features of social and labour market policy in the region (such as lifetime employment practice, generous enterprise welfare and seniority wages) underpin the protection of male breadwinners. While these elements facilitate the stable employment of male workers, they penalize female workers, whose employment is more likely to be interrupted by childrearing and other care responsibilities (Rosenbluth and Thies Reference Rosenbluth and Thies2010).

Since women in the family were regarded as primary caregivers, public policies promoting work/family reconciliation were underdeveloped in the region (Pascall and Sung Reference Pascall and Sung2007). In Korea, maternity leave was paid but short, and only mothers were entitled to unpaid parental leave (Ministry of Labour 2008a). Childcare was regarded as a private matter, and only some very limited public childcare was provided for low-income families. The rudimentary status of family policy reflected the low priority that work/family reconciliation received in the political domain. For instance, in its presidential campaign of 1997, the ruling conservative party pledged ‘housewife-friendly’ policies, which underscored the party’s deep commitment to the male-breadwinner ideology (National Election Commission 1998).

During the Kim Dae-Jung government (1998–2003), however, family policy underwent a first, cautious, expansion. Maternity leave was extended from two to three months. Parental leave became gender neutral, with its eligibility being extended to fathers, and more generous, although the newly introduced flat-rate monthly benefit of 200,000 won (approximately £110) was modest. Tax-funded free childcare for children aged five was introduced for low-income families. Also, private childcare was deregulated in order to increase childcare provision through the market (Ministry of Health Welfare and Family Affairs 2009). On balance, however, family policy under the first centre-left government remained modest. The modest nature of the expansion becomes even more evident when compared with the extensive reforms in other domains of social policy (e.g. the universalization of unemployment insurance and national pension schemes) during the tenure of the government. Considering that these reforms were geared towards protecting family wages earned by male breadwinners, it is clear that work/family reconciliation was not a priority.

The Expansion of Family Policy since the 2000s

With the election of the second centre-left government of Roh Moo-Hyun (2003–8), the development of family policy began to take a different trajectory. Moving away from strict means-testing, tax-funded childcare benefits were extended to middle-class families for the first time. In particular, a universal childcare subsidy was introduced, covering up to a third of the childcare costs for all children under the age of two in private childcare centres. Moreover, the government pushed for the public provision of childcare, which involved a greater financial commitment from the government than a market-driven approach. A National Childcare Strategy was drawn up for the first time, pledging to double the number of public childcare centres from 1,352 to 2,700 by 2010 (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family 2006). Accordingly, between 2003 and 2006, the childcare budget increased fourfold from 235 billion won to 1.04 trillion won (approximately from £131 million to £578 million); the majority of the budget increase was due to the expansion of childcare benefits (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family 2007). Furthermore, parental leave became substantially more generous. While the individual maximum leave duration of 12 months was not changed and the restriction prohibiting both parents from being on leave for the same child at the same time remained, the relaxation of eligibility (from the parents of children under the age of one to children under the age of three) effectively doubled the total leave duration for a couple up to 24 months. Also the flat-rate leave benefit gradually increased from 200,000 won to 500,000 won (approximately £278). Lastly, a three-day unpaid paternity leave was institutionalized (Ministry of Labour 2008b). These measures represent a visible enhancement of the state’s efforts to promote work/family reconciliation.

Under the following two conservative governments of Lee Myung-Bak and Park Geun-Hye, family policy stayed on the course of expansion. The continuous improvement in generosity and scope of childcare benefits led to a watershed in 2013 when childcare became free for every family. A similar trend was observed in parental leave schemes. The introduction of earnings-related benefits (at a 40 per cent income replacement rate – with a floor and a ceiling) effectively doubled the maximum amount of benefit to 1,000,000 won (approximately £556). The eligibility was also extended to parents of children under the age of six. Lastly, paternity leave was extended from three to five days, with benefits paid for the first three days (Ministry of Employment and Labour 2012).

It should be noted that, parallel to the abovementioned expansion of employment-oriented family policy, a ‘conservative’ measure was also instigated and expanded during these two governments. A home-care allowance was introduced by the Lee government with a limited eligibility and became universal at the beginning of the Park government. All families which do not use externally provided childcare for their pre-school children are now entitled to an allowance of between 100,000 and 200,000 won, depending on the child’s age (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2013). This gave rise to a debate on whether the new initiative diluted the employment orientation of family policy. However, given the impressive turn to the free childcare era and low generosity of the home-care allowance, it should be acknowledged that work/family reconciliation has been continually emphasized during the last two conservative governments. In addition, the budget commitment to the family and childcare continued to rise under the two conservative governments, from 6.1 trillion won in 2010 (approximately £3.4 billion) to 12.2 trillion won in 2013 (approximately £6.8 billion) (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2015).

The expansion of family policy represents a substantial decline of pure developmentalism in Korean social policy. Not only does it signify that non-productive populations (notably, women and children) are now ‘worthy’ beneficiaries of the welfare state in their own right, but it also facilitates women to ‘exit’ the role of unpaid carer, which was critical to maximizing state resource allocation for economic development. In the next section, the article examines the political underpinnings of family policy reforms, with special attention to the role of political parties. Before doing so, it first reviews the East Asian and Western welfare state literatures to show how the literatures treat political parties differently and how the insights from the Western literature can greatly contribute to enhancing our understanding of the role of Korean political parties in welfare politics.

KOREAN POLITICAL PARTIES IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

Partisan Politics and Western Welfare States

Political parties have been regarded as key actors in the rise and transformation of Western welfare states. The traditional partisan politics scholarship contends that parties offer distinctive platforms on the welfare state based on their ideologies. According to the ‘parties-matter’ literature, parties of the left are associated with more redistribution through the expansion of the welfare state, while parties of the right are associated with downward pressures on public expenditures (Castles Reference Castles1978; Hibbs Reference Hibbs1977). The difference in party platform on the welfare state is seen as the result of the parties’ class origins. In other words, a party’s ideological position on the welfare state is determined by the social class whose interest it represents. Similarly, the power resources thesis points to the impact of social democracy on the welfare state. By highlighting the role of organized labour in the establishment of social democratic parties, power resources theorists traced social democratic parties’ championing of the welfare state back to their working-class constituency (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1985; Korpi Reference Korpi1983). Therefore, the traditional partisanship literature sees parties as the agents of social class.

The traditional partisanship scholarship has been challenged by a plethora of literature suggesting that the party–voter linkage has been in flux as a result of substantial social changes since the 1970s. Class voting has been declining as the performance of parties and their stance on issues have become increasingly important to voters’ electoral decisions (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2007; Kayser and Wlezien Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011). In this context, the concept of party competition offers a powerful explanation of how parties actively exploit new opportunities brought about by social changes and the resulting more fluid party–voter linkages. Contrary to the traditional understanding of parties as the agents of social class, the party competition thesis sees parties as resourceful organizations with partial autonomy from social structures. Parties, in order to maximize voter mobilization, seek potentially popular issues that can draw in an array of new constituents and adjust their traditional (ideological) platform accordingly (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2007; Riker Reference Riker1986). Parties’ greater ability to adjust their platform to maximize voter mobilization is also supported by the literature on party organizations. The concept of catch-all parties and cartel parties suggests a much looser connection between parties and their electorate, as parties have reached out to a new constituency beyond their traditional supporters (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995).

One of the social changes that contributed to the fluidity in party–voter linkages and parties’ quest for new constituents is the entrance of women in the labour market on a large scale since the 1970s. Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994) pointed out the success of the left-wing parties in attracting new constituents among middle-class voters. In particular, these are younger, highly educated and highly skilled middle-class voters, among whom the number of working women has been on the rise. It is suggested that paid employment makes women more ‘left-leaning’ as working women display greater support for the welfare state, not only as an enabling tool for their employment (e.g. publicly subsidized childcare), but also as an important source of their employment (e.g. care service jobs in the public sector) (Greenberg Reference Greenberg2000; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006). Nevertheless, their entrance into the labour market means that women have to face social risks different from those that working men encounter (i.e. the interruption of employment due to pregnancy and motherhood) (Bonoli Reference Bonoli2007; Taylor-Gooby Reference Taylor-Gooby2004). The emergence of these ‘new’ social risks indicates that working women, of whom the majority are employed in the service sector, have policy preferences and priorities different from male industrial workers, the traditional core constituency of parties of the left. A growing body of literature has shown how left-wing parties adjusted their traditional platforms to address the policy preferences of working women (e.g. work/family reconciliation and gender equality) and how the parties’ success in mobilizing working women triggered right-wing parties to adjust their platforms in turn to appeal to working women. Here the concept of party competition has been at the centre of political explanations for the expansion of new social policies (see Ellingsæter Reference Ellingsæter2014; Fleckenstein Reference Fleckenstein2010; Morgan Reference Morgan2013 for European cases).

Partisan Politics and the Korean Welfare State

In contrast to the prominent role that political parties are ascribed in the development of the Western welfare states, parties are not deemed the key actor of welfare politics in Korea. It has been argued that the traditional partisanship literature offers little utility in explaining the development of the Korean welfare state. The thrust of such argument is that Korean parties are not policy oriented and they do not offer distinctive programmes (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008; Ringen et al. Reference Ringen, Kwon, Yi, Kim and Lee2011; Wong Reference Wong2004). Kim (Reference Kim2000) argues that the non-policy-oriented nature of Korean parties is attributed to the weak role that social class plays in political mobilization in Korea. He points out that deep-rooted Confucianism renders individuals to see their home region as one large family by emphasizing common bonds and interests.

This legacy had a profound impact on political mobilization, as individuals’ regional ties become a more critical element of identity than their class. In addition, the Cold War left long-lasting damage on the political left and the political mobilization of the working class. The scarring experience of the Korean War between the US-occupied South and the communist North created strong antipathy towards left ideology in South Korea, and the public was unable or unwilling to distinguish social democracy from communism (Kang Reference Kang2003). Consequently, political ideology was confined to the right end of the spectrum, limiting parties’ ability to compete on qualitatively distinctive ideologies and programmes.

To make things even worse, the long authoritarian rule further suppressed the development of electoral cleavages along the lines of social class. Under authoritarianism the room for genuine electoral and party competition was very limited at best. Parties were either an apparatus of military dictatorship, or organized opposition against it. Under these circumstances, parties were simply unable to function as an agent of class with an elaborated set of programmes. As policy issues were not salient for electoral politics, the ruling party largely delegated policymaking to the bureaucrats. The bureaucratic dominance in the policy process was well demonstrated by the developmental state literature, drawing on the experiences of Japan, Korea and Taiwan, especially in the area of economic policy (e.g. Johnson Reference Johnson1987). Similar to the developmental state literature, Goodman and Peng (Reference Goodman and Peng1996) and Kwon (Reference Kwon1999) also highlight the key role that bureaucrats played in social policy.

The insignificance ascribed to parties might have been expected to change in the aftermath of the democratic transition of the late 1980s. The regime-controlled change ensured stability during the transition period, which facilitated the opposition’s consolidation in the form of parties (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2016). The introduction of electoral competition opened up real possibility for parties to take up a key role in policymaking processes. Yet, the ‘parties do not matter’ perspective still prevails in the scholarship examining the politics of social policymaking in the democratic era. The developmental welfare state literature defends its corner by portraying bureaucrats as the key driver of welfare state expansion in the democratic era (Holliday Reference Holliday2005; Kwon Reference Kwon2003). Even the democratization literature fails to shed new light on parties. Wong (Reference Wong2004) argues that Korea’s democratization produced neither programmatic parties nor policy-oriented legislators.

Instead of well-developed sets of ideologies or programmes, it is argued that regionalism, which was underpinned by Confucianism, filled the vacuum in electoral politics created by the democratic transition. It is conventional wisdom in the Korean party politics literature that regionalism became the most dominant factor in electoral politics in the 1990s. This decade was known as the ‘three Kims era’, as the main political parties were essentially identified with three long-standing politicians (Kim Young-Sam, Kim Dae-Jung and Kim Jong-Pil) rather than with distinctive ideologies or policy positions (Kim Reference Kim2011; Lee Reference Lee1998). As noted earlier, Korean parties do not have close links with social classes, which prohibited them from mobilizing mass membership.

In essence, Korean parties were cadre parties, relying heavily on their leaders for campaign financing and in return giving leaders almost entire control over election campaigns (Hellmann Reference Hellmann2011; Heo and Stockton Reference Heo and Stockton2005). Because each Kim could draw loyal support from his region, parties were incentivized to exploit regional patronage for voter mobilization. Hence, the charismatic leadership of politicians very often featured more prominently than specific policy issues in election campaigns. Similarly, Haggard and Kaufman (Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008) contend that partisanship did not have marked effects on the welfare state development in the democratic Korea. They underline regionalism and the weakness of the political left as reasons why the traditional partisanship literature is not applicable to welfare state expansion in the democratic Korea.

While these scholars tend to downplay the role of parties on the grounds that Korean parties do not fit the traditional partisanship literature, they identify electoral competition as being key to the new dynamics of welfare politics in the democratic era. With the arrival of democracy, and ample room to explore welfare expansion given limited welfare provision and favourable economic conditions, ‘parties of all political stripes stood to gain by making social-policy promises’ (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008: 259). In other words, the introduction of genuine electoral competition turned social policy into a ‘winning platform’ (Peng and Wong Reference Peng and Wong2008; Wong Reference Wong2004). However, electoral competition is discussed in rather vague terms, telling us little about how and why supposedly non-policy-oriented parties began to ascribe prominence to social policy in election campaigns. It is especially puzzling, in light of the claim that public demand for the welfare state was negligible (Deyo Reference Deyo1992; Goodman and Peng Reference Goodman and Peng1996), that parties perceived social policy as a winning platform.

While explanations on these important questions are missing, the democratization literature highlights civil society as a source of bottom-up demand for welfare state expansion, and it portrays parties as merely transmitting civil society’s demands to policymaking processes (Y.-M. Kim Reference Kim2008; Peng and Wong Reference Peng and Wong2008; Wong Reference Wong2004). This emphasis on civil society can also be found in an emerging body of literature explaining the politics of family policy expansion in Korea. In particular, ‘femocrats’ with civil society activist backgrounds are identified as the key driver (Estévez-Abe and Kim Reference Estévez-Abe and Kim2014; Peng Reference Peng2004; Peng and Wong Reference Peng and Wong2008). This research will show that despite the femocrats’ passionate championing of family policy reform, due to their ‘powerlessness’, the reform would not have happened in the absence of the reform impetus provided by political parties. Moreover, it will also show that when femocrats were sidelined under the recent conservative governments, the incumbent party continued to expand family policy.

To fill the gap in the literature, this article draws on recent party politics scholarship illuminating the autonomy of parties in adjusting to the changing party–voter linkages. The scholarship offers a great insight in light of important changes in the Korean electorate that occurred in the last two decades. First, the significance of regionalism, the key factor undermining the policy orientation of political parties in Korea, has been decreasing since the retirement of the three Kims. Second, a generational change in the electorate has been observed. At the start of the 2000s, a younger generation in their twenties and thirties showed great concern about political ideologies and displayed more sympathy for left ideology – unlike the older generation in their fifties and sixties. The interaction of the two factors led to the increasing importance of policy issues in electoral politics. It is this context of the generational change of the electorate that triggered parties to move policy issues to centre stage in their electoral campaigns. Thus, the absence of a class base is not a stumbling block for parties in becoming policy oriented. In fact, it is argued here that the absence of class-based mobilization allowed Korean parties more flexibility in adopting new election strategies, in which policy issues – including the welfare state – were given prominence. Utilizing insights from the recent partisanship scholarship, the following section shows how political parties emerged as the driver of family policy reforms in Korea and explains why non-policy-oriented parties have ascribed great prominence to family policy in their election campaigns.

EXPLAINING THE POLITICS OF KOREAN FAMILY POLICY REFORMS

Political Parties as Key Agency

The investigation into the role of political parties indicates that parties were at the centre of the reform process. First, political parties were the most critical actor which set the work/family reconciliation issue as an important item on the agenda. Since the early 2000s family policy has become politically salient through election campaigns. In the 2002 presidential election, the centre-left and conservative parties converged on the issue as the latter made a policy U-turn and joined the former to promote female employment and the socialization of care (Grand National Party 2002, 2007); the centre-left party responded to the conservatives’ policy U-turn with a promise of greater policy reforms to consolidate their progressive appeal (Democratic Party 2002, 2007). Therefore, due to convergence on the issue, the two main parties have tried to outbid each other, making bolder pledges on the expansion of childcare benefits, childcare provision and care-leave schemes (interviews with three representatives of the Democratic Party and the Grand National Party, 21, 27 and 28 September 2010). Bolder pledges on this issue also translated into giving family policy greater weight in general election strategies. Quite different from the active role of parties as agenda-setters, no ministry was seriously interested in the issue until recently except the Ministry of Gender Equality (Ministry of Labour 2008a; interview with a gender equality bureaucrat, 9 September 2010). Yet, this ministry was not in a position to put family policy expansion on the agenda as it was largely powerless due to its symbolic role and small budget (interviews with gender equality bureaucrats, 9 and 20 September 2010).

Second, it was the political parties that steered the implementation of family policy reform. When in power, both political parties reshuffled government ministries in order to spearhead family policy reform according to their preferences. During the Roh government, the centre-left party promoted the Presidential Committee of Women’s Affairs to the Ministry of Gender Equality and transferred childcare policy to this newly established ministry from the powerful Ministry of Health and Welfare. This was done because the party considered feminist agency a better vehicle to promote its progressive childcare platform (interviews with two representatives of the Democratic Party, 9 and 21 September 2010 and with a gender equality bureaucrat, 16 September 2010). In addition, some cabinet members of the Roh government, who had previously held senior positions within the centre-left party, initiated the establishment of the Presidential Committee on Low-Fertility and Ageing Society, which was instrumental in spearheading family policy reform. The committee dubbed the fertility decline a ‘major crisis’ (Government of the Republic of Korea 2009), similar to the Japanese ‘1.5 low fertility shock’ of 1989. As the discourse on the ‘low fertility crisis’ turned out to be an effective means of gaining public support, family policy was then also promoted as a pro-natal measure (interviews with two representatives of the Democratic Party, 9 and 21 September 2010).

In the same vein, when the conservative party returned to government in 2008, it implemented family policy reform through its preferred ministry. The childcare policy was transferred back to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, as the party wanted to emphasize its ‘child-wellbeing-centred’ platform (as opposed to the ‘feminist’ stance of the Roh government) on family policy (interviews with three health and welfare bureaucrats, 15, 16 and 20 September 2010). The conservative government also continued using the Presidential Committee on Low-Fertility and Ageing Society as the main forum for reform deliberations, where family policy was highlighted as a tool to boost fertility. However, family policy reforms should not be relegated to a mere response to fertility decline, given that family policy entered the political agenda prior to the pro-natalist policy discourse.

It should be noted that, at first, parties – based on electoral strategies – championed family policy in the context of promoting female employment and work/family reconciliation, and not as a means to raise fertility. In the 2002 presidential campaigns, both the conservative and the centre-left parties promoted family policy without an explicit link to fertility decline. It was only after the Presidential Committee was established in 2005 that the parties spun the reforms as an instrument to raise fertility.

Third, parties also played a key role in securing the necessary budgets for family policy reforms. Specifically, parties were able to override the fierce opposition from economic bureaucrats, notably the Budget Bureau (interviews with two health and welfare bureaucrats, 6 and 20 September 2010, and with two gender equality bureaucrats, 9 and 16 September 2010). During the Lee government, the conservative party defended the budget plans drawn up by the Ministry of Health and Welfare at party-government meetings, wherein the leadership of the incumbent party met with high-level bureaucrats to decide on priority agendas (interview with a representative of the Grand National Party, 15 September 2010).

Furthermore, in the case of care-leave reform, parties even bypassed bureaucratic apathy through the legislature. The ministry of Labour, which was in charge of care-leave schemes, was reluctant to push for the reform. Although the ministry supported the expansion of the schemes in principle, it was divided on whether expansion should be funded by the Employment Insurance Fund. The Bureau of Female Employment Promotion was in favour of using the fund for the reform, whereas other bureaus were strongly against the idea, being concerned that it would hamper the fiscal stability of the fund (Ministry of Labour 2008a). While the ministry was mired in internal divisions, political parties took the legislative initiative. Unlike the convention that reform bills were submitted by government ministries, care-leave reform bills were submitted by parties and then approved by the National Assembly. This reform episode corresponds with the trend that parties had begun to exercise their legislative authority proactively since the democratic transition. During the last two decades, the number of bills submitted by parties has gradually increased, and finally, in the 2000s, party bills outnumbered government bills (National Assembly 2012). Thus, it can be said that political parties evolved from being mere ‘rubber stamps’ of government proposals and developed into actors in their own right in policymaking.

This section has shown that political parties, not bureaucrats as perceived wisdom suggests, were the driver of family policy reforms. They provided political salience to the reforms and found ways to overcome bureaucratic apathy for or opposition to the reforms.

Why Have Parties Moved Family Policy to the Centre Stage of Electoral Politics?

Entering the 2000s, a change in the dynamics of electoral behaviour has been observed. In tandem with the retirement of the three Kims, the impact of regionalism on electoral behaviour began to decline. For instance, Roh Moo-Hyun gained only 52 per cent of support from the centre-left party’s regional base of Cholla Province, which was substantially lower than the 93 per cent his predecessor Kim Dae-Jung had received (Kim Reference Kim2011).

At the same time, a visible generational cleavage emerged: while younger voters preferred progressive forces, older voters supported the conservatives (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Choi and Cho2008). Specifically, Byung-Kook Kim (Reference Kim2008) points out an electoral cleavage between the ‘5060 generation’ (people in their fifties and above) and the ‘386 generation’ – the appellation coming from their age (30–39 years old), their decade of college entrance (1980s) and their decade of birth (1960s), at the time of the 2002 presidential election. What made the emergence of the progress-oriented young voters more notable, and thus made their support critical for electoral success, was the size of the age group. In 2002, voters in their thirties constituted the single largest age cohort of the electorate (B.-K. Kim Reference Kim2008).

The interaction between the decline of regionalism and the rise of younger voters with stronger ideological orientation led to the growing importance of policy issues in electoral politics. By 2007, policy issues had become nearly as important as the personality of candidates in determining voters’ choice, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Key Determinants of Voters’ Choice in Korean Elections (in percentage)

Source: Korean Election Survey, Korean Social Science Data Centre (1997, 2002, 2007).

In addition, the generational change of the electorate provided a more fertile ground for pro-welfare state platforms. Public support for expansion of the welfare state, even at the expense of higher taxes, has been growing, as shown in Table 2. By the time of the 2002 election, more than half of voters were in support of welfare state expansion. What is even more noteworthy is the rapidly growing support for the policy among women voters since the 1990s. In light of the evidence that Korean women had been ideologically more conservative than their male counterparts (Wade and Seo Reference Wade and Seo1996), the fact that women are fast catching up with men on support for the welfare state suggests that the traditional gender gap (i.e. that women typically voted to the right of men and had a more conservative ideological stance than men; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2000) has been closing. In the most recent presidential election of 2012, the gender gap on support for the welfare state had almost closed. Equally important, the gender gap in voter turnout has not only been closed but even reversed, as shown in Table 3, putting ever increasing pressure on parties to appeal to women voters.

Table 2 Growing Support for Welfare State Expansion

Source: Korea Gallup Survey (1993, 1998) Korean Election Survey (2002, 2012).

Note: The table shows the percentage of respondents who answered either ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ to the statement, ‘The welfare state should be expanded even if it requires a tax increase’. The two surveys asked essentially the same questions – there was no meaningful difference in the wording of the questions.

Table 3 Trend of Gender Gap in Voter Turnout for Presidential Elections

Source: Voter Turnout Analysis for the 1997 and 2012 Presidential Elections, National Election Commission.

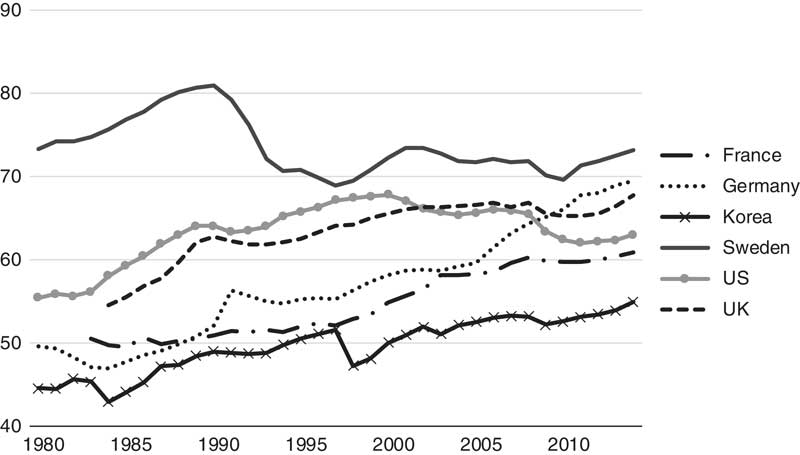

The closing of the gender gap took place against the background of growing female employment. Since the mid-1980s women’s entrance in the labour market has been on a steady increase, almost catching up with the OECD average in the 2010 (see Figure 1). Moreover, in terms of full-time equivalent employment rates, Korea (with 57 per cent in 2014) is ahead of many Western countries (e.g. OECD average 51.2 per cent) (OECD.Stat 2016).

Figure 1 Female Employment Rates, 1980–2014 Source: OECD.Stat (2016).

Coinciding with the generational change in the electorate, parties have ascribed greater importance to social policy since the 2002 presidential campaigns. The nomination of Roh Moo-Hyun as presidential candidate meant that the centre-left party needed to consolidate support from progressive voters in order to win the election. Roh’s ties to Cholla Province, the stronghold of the party, were rather weak, as he was born and established his political career in Kyongsang Province, the stronghold of the conservatives. Meanwhile, he drew strong support from young progressive voters of the 386 generation due to the reformist image he had earned as a human rights lawyer and legislator. Therefore, it became an integral part of the party’s campaign strategy to secure the support of these voters.

Against this background, social policy appeared to have more instrumental value than ever to the centre-left party. Among the sub-domains of social policy, family policy was chosen to showcase the party’s commitment to the welfare state for two reasons. First, as a new social policy dealing with new social risks, family policy had more room for expansion than old social policies (e.g. pensions and health insurance, and public assistance schemes) which had already experienced comprehensive reforms. Second, and more importantly, family policy was considered strategically significant in attracting young voters, especially young women voters, who were deemed particularly responsive to benefits for young families with pre-school children. According to the 2003 Korean General Social Survey data, an overwhelming majority of young voters (in their twenties and thirties) supported family policy; the level of support was particularly high among young women (86.3 per cent) as compared to the still impressive support from young men (74.2 per cent).Footnote 1

However, Roh’s popularity among the young voters was by no means unchallenged. It was put to the test when Chung Mong-Joon, an independent candidate, entered the electoral race just two months before the election. Campaigning on a similarly progressive platform to Roh (Walker and Kang Reference Walker and Kang2004), Chung garnered strong support from young voters. Particularly threatening to Roh was his popularity among young women, as Chung enjoyed support from 44.3 per cent and 35.7 per cent of women in their twenties and thirties respectively at one point (Seoul Shinmun 2002). Chung’s platform on gender equality was considered by far the most progressive one, including the appointment of a female prime minister, introducing a 50 per cent quota for women candidates for the party list, the complete abolition of the patriarchal family register system (hoju-je), and free childcare for children under the age of three and an increase in the share of public childcare by 30 per cent (Chosun Ilbo 2002a). Chung’s high popularity among young women voters was perceived as a threat by Roh’s election camp, making it imperative that they won back these voters ‘stolen’ by Chung. In this context of competing over young women voters, Roh announced 10 bold pledges for women, including the creation of 500,000 jobs for women, an increase in childcare benefits to up to the half of childcare fees, and the introduction of a 50 per cent quota for women candidates for the party list for the National Assembly elections (Chosun Ilbo 2002b; Seoul Shinmun 2002).

Family policy became an even more key electoral issue when the centre-left and conservative parties began to compete over young voters. Traditionally the conservative party paid little attention to young voters as its support base was anchored in regional voters in Kyongsang Province and voters of the 5060 generation (B.-K. Kim Reference Kim2008). There had been growing awareness of the importance of young (women) voters, however, since the party lost a presidential election for the first time in 1997. Reflecting this growing awareness, not only was the ‘housewife-friendly’ platform discarded but pledges for family policy expansion were adopted in the 2002 presidential campaign (National Election Commission 2009).

This policy U-turn by the conservatives created party competition on female employment and work/family reconciliation issues in the 2002 presidential election. The consecutive electoral defeat in 2002 made the party realize that it was imperative to be even more attractive to young voters, whose support was considered the key to the party’s rival’s somewhat unexpected electoral victory. Facing the 2007 presidential election, therefore, the conservative party seriously endeavoured to mobilize young, especially young women, voters, whose support for the party had been weak (interview with a representative of the Grand National Party, 28 September 2010).

The party’s commitment to mobilize young voters was reflected in the organization of Lee’s campaign team. First, Chun Jae-Hee, a female legislator with a long record of work/family reconciliation advocacy, was appointed one of the two deputy chiefs of the campaign team (Donga Ilbo 2007), demonstrating the party’s determination to devise a comprehensive family policy platform (interview with a former representative of the Grand National Party, 15 September 2010). Moreover, the ‘2030 team’ was set up specifically to channel the voice of young voters in their twenties and thirties into Lee’s campaign (Seoul Kyungie 2007). At the same time, the party strove to please its traditional conservative supporters by promising support for male-breadwinner families, most notably through a home-care allowance. The catch-all party strategy in the family policy platform was also employed by the party during 2012 presidential election campaign; Park Geun-Hye promised free childcare for all as well as a full-scale expansion of home-care allowances.

This section has shown that party competition on family policy has emerged as a way to adapt to the generational change of the electorate. With the rise of younger voters, policy issues have become much more critical in electoral decisions, and parties realized the instrumental value of family policy to appeal to young voters.

CONCLUSION

This research has shown that family policy reforms since the 2000s pose a great challenge to the developmental bias in the Korean welfare state. Before the 2000s, the financial commitment of the state to the family was almost non-existent. More than a decade after the 2002 presidential elections, when family policy became a key election issue for the first time, social expenditure on families has experienced a record increase. Given that women were considered to ‘function’ as unpaid carers in the developmental welfare state, it can be said that women gained the most from the reforms of family policy. It signifies that women and children, the non-productive population formerly excluded from the welfare state, are now at the centre of welfare state expansion.

This research has also demonstrated that political parties were in the driving seat of these important reforms, suggesting that parties have become key actors in Korean welfare politics. Despite rich scholarship highlighting their prominence in the development of Western welfare states, political parties have not received due attention in the study of East Asian welfare states, shadowed by the dominant bureaucrat-centred perspective. Parties have been regarded as irrelevant to social policymaking in East Asia on the grounds of their non-policy-oriented nature. This conventional wisdom has not been questioned, even by the democratization literature, which points to the changing nature of welfare politics in the reform of East Asian welfare states, but left the role of parties in the reform under-studied. The research presented here has filled this gap in the East Asian welfare state literature, specifically by showing how and why parties moved family policy to the centre stage of election campaigns. Drawing on the party competition thesis, this article has demonstrated how Korean political parties adjusted their platforms (from personality- to policy-centred) in the face of changing electoral behaviour and preferences. Far-reaching changes in the electorate, namely the diminishing effect of regionalism and increasing importance of young voters, incentivized parties to promote family policy. Thus, this research calls into question the conventional wisdom that political parties in East Asia are insignificant in social policymaking and calls for bringing political parties to be brought into the analysis of welfare state reform in the region.