1. Introduction

I have been concerned with the issues discussed in this article for a long time, which also found expression in some of my earlier work (Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta and Bilińska-Suchanek2006, Reference Szczurek-Boruta2007).

Seeing a gap in pedagogical research on youth developmental tasks and the limitations of the existing research, which tends to have been fragmentary and narrowed to one discipline or specialization, I undertook in the school year 2003/2004 a comprehensive study of youth developmental tasks and the social conditions of school education. The neglect and deficits revealed at that time, both in the performance of the developmental tasks by young people and in the extent of a school not fulfilling its tasks prompted me to repeat this study 13 years later.

The structure of the considerations undertaken in this article is determined by the holistic and dynamic approach. It allows for recognizing the mutual conditioning of identity and school as inseparable and dynamic systems. Such an approach takes all external and internal impacts on the student and school into account as well as the inseparability of the micro (a human individual as a system), meso (school as a system) and macro (society) perspectives.

I believe that considering the issue of youth identity and the functioning of schools as autonomous, independent systems is not sufficient. A comprehensive, multifaceted approach contributes to a better design of educational activities. It is a perspective that involves asking questions about the essence, dynamics, validity of cognition, the validity of the principles of evaluation, and the causative power.

I conceptualize identity as consisting of a number of constant components constructed in the course of social interactions; a structure (Marcia Reference Marcia and Adeloon1980, 159) composed of a number of developmental tasks that are related to each other – a structure that is solid, open and dynamic (Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta2019).

I assign a significant role to school as a factor in the process of shaping youth identity. School is an element of a broader social system, a whole reflecting the dynamic interrelationships between its various components, and any change in one of the elements entails changes of the other elements and, as a consequence, of the whole system.

2. Theoretical and Methodological Assumptions of Research

In the theoretical construction, in the approach and in the interpretation of research results, I have adopted an eclectic approach. I make reference to psychological, sociological and pedagogical theories, including the theory of psychosocial development by Erik Erikson (Reference Erikson1968, Reference Erikson1994 and other works), the concept of developmental tasks by Robert Havighurst (Reference Havighurst1953, Reference Havighurst1981), Jan Szczepański’s concept of the social conditions of education (Szczepański Reference Szczepański1989), the theory of reproduction by Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1990) and Bogdan Nawroczyński’s universal pedagogy of culture (Nawroczyński Reference Nawroczyński1947).

I am interested in young people as a force shaping the future of society, an element of culture, a social group of a subjective character faced with the challenge of identity formation, which is a significant generational experience, as this challenge is clearly felt by the group and must be addressed. Adolescence is one of the most difficult stages in a human life. The crisis that then occurs, with its depth and reach, exceeds all other crises related to development experienced in a lifetime. The existential task often proves to be beyond the strength of a young person. It is sometimes a time of dramatic attempts to rebuild his or her own identity (Erikson Reference Erikson1994, 53–57).

I consider research on youth as significant, as this group is a barometer of social change, a driving force of progress. It determines the future of the world and the economy that is already adapting to the needs of the to-be consumers.

The study covered two generations: Y and Z. These two generations together form the most numerous generation group in Poland, hence their importance for society is enormous (Sadowski Reference Sadowski2018).

Generation Y can remember political transformations in Poland at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s, the pre-internet times, Poland’s accession to the European Union, borders between counties, joining the Schengen Area. Their legacy was different from Generation Z’s. They suffered shortages in many spheres, e.g. lack of goods in shops, queues, and no common access to the internet. In their childhood, the representatives of Generation Y did not use media to such an extent as Generation Z (Generations X Y Z 2018).

Representatives of Generation Z were born in the world dominated by technology, they cannot live without the internet and new technologies, of which they are fully aware. Many studies seem to confirm that those who belong to Generation Z declare that customization is of great significance to them, it is a manifestation of the individuality of needs; digital communication is more convenient to them than traditional interpersonal contact; the borderline between the virtual and real world gets blurred, they value their close friends as equally well as their friends from social media.

Both generations were educated in a different system of school education, according to different curricula.

Generation Y went through the two-stage system (primary school, secondary school), which had been introduced in 1968, whereas Generation Z were educated in the three-stage system (primary, lower-secondary, upper-secondary school).

Following Erikson (Reference Erikson1968), I consider identity as an aspect of personality that determines its degree of integration. It is a complex whole which gives life a direction, a system responsible for a specific way of behaviour, a system integrating developmental tasks (after Havighurst Reference Havighurst1981, problems to be solved, social expectations to which the individual gives individual content), enabling the adoption of a stable commitment to a specific set of goals, values and beliefs.

School is an institution of social education and as such it is expected to ensure adequate conditions for the development of each individual. It is a carrier of values and experiences, a place to meet students’ needs, to let them know each other and the world.

Education in the Republic of Poland is a common good of the whole society. It is guided by principles contained in the Constitution of the Republic of Poland in addition to the postulates contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In accordance with the current act on the education system (Journal of Laws 1991, No. 95, as amended, item 425, Article 13, paragraphs 1 and 4), Polish schools should enable students to maintain a sense of national, ethnic, linguistic and religious identity, in particular through the study of their native language, history and culture. Public schools also ensure the maintenance of regional culture and tradition.

Recognizing the dependence of the individual’s psychosocial development processes on the quality of the social offer, I assume that satisfying the existential need characteristic of the fifth stage of psychosocial development is hardly possible without external support in the form of natural and intentional educational interventions.

School education is part of the process of shaping the identity of new generations. In addition to family socialization and the socialization taking place in the local environment, it is one of the active links providing students with knowledge, experience and identification models. It enables experimentation with social roles, creates opportunities for developing a sense of loyalty to ideals and motivation to take initiative in action.

Following comparatists’ thought, it should be highlighted that education is anchored in the social and cultural context (Sadler Reference Sadler1979), in the contexts of a nation’s characteristics, geographical location or culture (Manzon Reference Manzon2018). Social, economic and cultural systems are interrelated (Alexander Reference Alexander2000). What takes place outside school is the basis for understanding the system of education. The awareness of the historical-cultural context in which education has developed and a skilful analysis and interpretation of educational phenomena can contribute to predicting changes in the functioning of a school.

I assume that the tasks of education are formulated against the background of social expectations, social cultural and economic conditions as well as the context of the times. These tasks include: providing offers of identification, extending the range of interactions, ethos, ambivalence, revitalization, and extending the developmental moratorium (Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta2007). The tasks identified – the categories adopted from Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development and empirically verified during the author’s study conducted in 2003/2004 – guide and actuate the activities of teachers and school. They bring specific results, both in the subject (the identity of a young person) and often in other elements of the school as a system.

Growing up – according to Erikson (Reference Erikson1994, 78) – forces one to experiment, accept and reject a number of roles on offer. The number of possible identifications available to a young person is essential when they reach the stage of being willing to experience different roles. Given young people’s natural tendency to experiment with social roles, the educational system must offer a range of possible alternatives.

A young person desires recognition from other people. This leads youth to observing others, imitating them, modelling them, daring to go beyond the circle of parents and teachers, unlike in the previous phases. There is a significant expansion of the circle of potential models, which is necessary for ‘role experimentation’ and thus extends the range of social interactions. The ways that interaction influences who a person is become important not only from the perspective of shaping the identity of an individual (self-assessment, providing criteria for measuring one’s own success or failure, negotiation for a space of recognition that is demanded from others), but also in terms of the tasks of the school (preparation for life in society).

The ethos is the existential basis for the possibility of realizing the need for identity (as well as a source of new potential threats to further development). According to Erikson (Reference Erikson1968, 233), ethos is an ideology that is institutionally present in society, an expression of the need for and the vital force of ‘loyalty’. An adolescent young man is looking for people and ideas that he can be faithful to and thus feel valuable and gain credibility. The primary task of school is to provide experiences that will allow youth to build their own ideology.

Ambivalence (bivalence, ambiguity or even multiple ambiguity and the mutual opposition of the perceived and experienced world) is imprinted in the reality of school in both material and spiritual dimensions. Ambiguity is intertwined in the complicated mechanism of the organization of the educational process, resulting from the high degree of complexity of school reality (Witkowski Reference Witkowski, Brzeziński and Witkowski1994; Gnitecki Reference Gnitecki1994). School must develop sensitivity to ambiguity in both students and teachers and show young people how to deal with ambivalent situations.

The sense of revitalization generates the desire to change, integrate and do things in a perfectionist manner. For an individual, it means understanding the world and its tools in culture, gaining experiences, becoming a member of various communities while keeping the awareness that the social relations within them are subject to change. It is a time of departure from the ‘role identity’ pattern, which is extremely defined in school practice and developed in the fifth phase of psychosocial development, towards consolidating one’s identity needs around one’s individual skills, e.g. social, technical and professional skills.

One of Erikson’s developmentally distinguished forms of reacting by adolescents to the role and offer of identification that they find in society is a moratorium. It is a period of delay, postponement, a grace period granted to those who are not ready yet to face their duties, who need more time (Erikson Reference Erikson1968, 157). The task faced by a young person and their environment is very difficult. It requires adequate duration, intensity and ritualization of adolescence, which is different from individual to individual. Societies offer, as expected by individuals, more or less authorized intermediate periods between childhood and adulthood, specific developmental moratoriums, during which the permanent pattern of internal identity is subject to relative actualization (Erikson Reference Erikson1994).

While focusing on selected tasks of education which, according to theoretical assumptions, are conducive to satisfying the need for identity and the fulfilment of developmental tasks characteristic of Erikson’s fifth phase of psychosocial development, I attempt to answer the following question.

Which tasks of education, in the opinion of young people surveyed at two points in time (in the school year 2003/2004, and 2016/2017), are successfully carried out by school and which are not?

The pedagogical reflection conducted in this article begins with diagnosis, it serves the acquisition of new knowledge about the foundations of phenomena and observable facts, but also aims to clarify, interpret and compare the research results obtained. It is intended to facilitate discussion about the possible solutions to theoretical and practical problems that will appear in the context of research and its results.

This research undertaken in the field of pedagogy follows the scheme of a survey and comparative studies (Konarzewski Reference Konarzewski2000). I use one of the three research strategies found in the psychology of human development, namely the sequential research strategy, typically used for the study of different people at different times, but they are similar in terms of their age. Within this strategy, I used a cross-sequential study (Schaie and Strother Reference Schaie and Strother1968, 671–680; Bee Reference Bee2004). I carried out measurements of a given variable (developmental tasks, tasks of school) with the same tool and in a repeatable manner but at different times and with different groups of respondents all of the same age.

This article uses part of the empirical material of the author’s nationwide quantitative and qualitative research conducted in the school year 2003/2004 and part of the data collected during research conducted in the school year 2016/2017.Footnote 1 In this article, only the quantitative data are considered (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias Reference Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias1996, 153–154; Rubacha Reference Rubacha2008), found by using my own questionnaire based on Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, Havighurst’s concept of life tasks, Lewowicki’s Theory of Identity Behaviours, and sociological theories of conflict. The questionnaire is included in Szczurek-Boruta (Reference Szczurek-Boruta2007, 381–384) and Szczurek-Boruta (Reference Szczurek-Boruta2019). Taking into account the accepted reliability of the tools employed, it can be concluded that the results obtained during this research project are a reliable indicator of the relationships between the analysed phenomena occurring in the sample group (Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.730 for the 2003/2004 study; Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.698 for the 2016/2017 study) (Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta2007, 178–183; Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta2019, 29).

I collected data on two different demographic cohorts, grouping people born in a given year, surveyed at two separate points in time (in the school year 2003/2004 and in the school year 2016/2017). I surveyed 18-year-olds at different times, i.e. people born in 1985, belonging to generation Y and people born in 1998, referred to as generation Z (Tulgan Reference Tulgan2009; Meister and Willyerd Reference Meister and Willyerd2010).Footnote 2

In the school year 2003/2004, 195 students participated in the study and in the school year 2016/2017 it was 248 students. The requirement for each sample is its maximal representativeness in relation to the population from which the sample was extracted. Multilevel sampling was chosen: a random choice of schools and of classes within them. This was done with the use of the random numbers generator of STATISTICA 5.1 software. Taking into account that, in social sciences, a representative sample is 5, 10, 15 classes, p<0.05, eight classes were accepted for the research (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias Reference Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias1996; Ferguson and Takane Reference Ferguson and Takane1989). The cohorts are not equal as the numbers of learners in the examined classes in 2003/2004 and in 2016/2017 were different.

The sample group was selected using the target-randomized selection and it meets the criteria of a representative sample. The target elements are: age of students – 18; type of school – secondary school; research territory – the Silesian Voivodeship, a zone with intensive economic development.

The Silesian Voivodeship is located in Southern Poland, and borders the Czech Republic and Slovakia. It is a local government unit and an administrative unit of Poland that covers the area of 12,333.09 km2 and is inhabited by 4.52 million people. It is the most highly urbanized and most densely populated voivodeship. The seat of voivodeship authorities is in Katowice. The gross domestic product per capita was 44,300 PLN (105.8% of the national average), which ranks the Silesian Voivodeship as the fourth among other voivodeships (Rocznik Statystyczny Województw 2014, 625). The Silesian Voivodeship comprises the south-eastern part of historical Silesia.

The industrialization of the region, a favourable local labour market (low unemployment), a high gross domestic product per capita compared with the rest of Poland, constant population growth, negative migration balance, concentrated and diversified schools, and the great number of socio-cultural institutions and organizations have consistently offered favourable conditions for education and life to the inhabitants of the Śląskie Voivodeship, an area experiencing intensive socio-economic development (CSO data on the Śląskie Voivodeship 2017). The richness of the region’s cultural potential (Eckart and Krahe Reference Eckart and Krahe2003; Ćwikła et al. Reference Ćwikła, Gnieciak and Wódz2019) shapes the group’s sense of value, increases self-esteem and motivates initiative.

The research data collected were verified using the methods of quantitative research analysis. Statistical methods were used for the analysis of the empirical data obtained, i.e. canonical analysis and descriptive statistics (Ferguson and Takane Reference Ferguson and Takane1989).

3. Discussion of Research Results

I assumed that the mastery (fulfilment) of an existential task (satisfying the need for identity according to Erikson) involves the necessity to synthesize (master) a number of individual developmental tasks (after Havighurst). Based on the sense of accomplishment of developmental tasks by young people, I make conclusions about identity and its formation, and about the youth’s condition and development.

The results of the research conducted show that representatives of two generations – Y and Z – although different, are similar to each other. They are subject to the same universal logic of development as living beings (agreement of the development process with the laws of nature) and as social beings (they live among other people); they live in the same territory, in similar socio-cultural conditions, they live at the turn of the century, in the era of rapid development of information and new technologies.

The similarity of the results between the two cohorts is probably due to the repeatability of the development pattern. The respondents belong to the generational group of secondary school students. The two sample groups have a greater number of common compared with differing features, which is why many researchers embrace both generations with one term – the Millennials (Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change 2010). Their developmental accomplishments are similar as they are the effect of participation in similar school situations, and these result in shared experiences in a given historical time. At the same time, however, this development followed various paths, was shaped by the combination of individual experiences, non-punctual biological (accelerated/delayed puberty) and social events, and unexpected life events (traumas, crises), both positive and concerning events. It should be noted that the childhood of these groups coincides with the time of the information society, network society, media society, and age of accessibility. There is a similar quality of developmental and educational offers and the ways of taking advantage of them by the two cohorts. Models of identity will always be grounded in the socio-cultural, and hence territorial, context. These contexts are a source of identity forming (they provide information on who one is and who one wants to be). Placed among various factors, an individual draws some self-defining elements from all of them and combines them with mental factors. Both Y and Z generations of young people achieved a similar general identity profile, and they have the same deficits in the performance of individual developmental tasks, e.g. they do not understand the problems of the surrounding world and do not engage in activities for the benefit of the country, ecology, and world.

Schools lead young people with different personal and social resources and living in different historical and socio-cultural times to a similar value of identity capital (the overall result of generation Y for the performance of all developmental tasks/developing a sense of identity, is slightly higher than the result of generation Z). The differences between the cohorts are insignificant, and the dynamics of change can be seen as quantitative, i.e. observed as an increase or decline in the degree of fulfilment of individual developmental tasks (see Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta2019).

Schools have reproduced and continue to reproduce behavioural patterns through specific social practices (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1990). Socialization practices dictate specific expectations of individuals and members of various groups. The similarities in social expectations, which are individually interpreted by young people through the developmental tasks, are also the manifestations of the impact of a common culture and social pressure.

Culture determines the meanings attributed to various behaviours, responsibilities or instances of growing into stereotypes. The world of culture and the personality of a young person may interact with each other passively or actively. The novelty and the pioneering character of the thoughts of the Polish culture educator Bogdan Nawroczyński consist in formulating such goals and norms of education which, based on values, guide the process of education towards the emerging future of society and culture. Nawroczyński (Reference Nawroczyński1923, 9) is aware of the fact that:

education has not only adaptive functions, but should also promote development and prepare the young generation to create new forms of social life, culture and civilization. […] This, in turn, requires not only forming a disposition for active and creative life, not only ensuring favourable conditions for the development of outstanding individuals, but also orienting oneself in the developmental tendencies of social life and bringing them into the process of education.

This pedagogue rejects both extreme socio-cultural determinism and unlimited freedom in creating educational goals and pedagogical norms.

Pedagogy views culture as an educational institution, an impulse that penetrates the meaning and the methods of educational practice. By participating in culture, an individual achieves a greater ability to live, a deepened sense of the meaning and value of life, an ability to communicate with other people.

Human functioning is immersed in the context of time (past, present and future create a horizontal dimension of development) and in the socio-cultural context (networks of relationships, multiple roles, vertical dimension of current functioning). In their development, young people undergo similar training and are subject to similar influences. The process of socialization taking place within a specific culture may be viewed as a kind of programming of the individual and of entire social groups (Hofstede et al. Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010). The common interest and the strategic goal of school and society leads to the creation of similar forms/models of identity. The educational environment is based on universal values which are the result of the impact of a shared culture. That culture is also strongly associated with the place of life.

The studies were conducted in the territory of the Silesian Voivodeship, which is in the south-eastern part of Silesia – a historical region of Poland. This area was chosen because it is an example of a Polish relict region (the others are Greater Poland, Lesser Poland and Mazovia) which in the past had constituted a separate political and administrative unit (in Poland, this is the legacy of the territorial partitions of Poland). The name of the region has been preserved in its unchanged form and is used in everyday life.

Silesia is inhabited by the national groups of Poles, Germans, Czechs and the population that call themselves Silesians in the sense of a separate nationality (the Silesian nationality is not officially recognized in Poland). Depending on the exact location of residence, the population of Silesia communicates in the Polish, German or Czech language, as well as the Silesian dialect of Polish (in certain environments considered as a separate language).

Silesia is a specific cultural melting pot, an area of distinct identity, which is traditionally cherished in the local culture (Lipok–Bierwiaczonek Reference Lipok–Bierwiaczonek1994; Bazielich Reference Bazielich1995).

A fundamental and inalienable feature for Silesians is family. Its high rank in the structure of values mostly results from historical determinants. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, the model of the ‘fortress family’ has dominated – the family which, in the face of denationalization processes, especially Germanization (particularly visible in the cultural space of Silesia), kept its cultural identity and became the core of the national life (Świątkiewicz Reference Świątkiewicz and Świątkiewicz1994, 43).

The course and shape of socio-cultural processes in this territory has been largely determined by the stereotypical (but consolidated in the social awareness) perception of Silesians as homo religious – indigenously religious people (Świątkiewicz Reference Świątkiewicz1997, 36–37).

The ethnic and cultural uniqueness of the indigenous population relates it to Catholicism and its rituality, as well as to Slavic (Polish and Moravian) local dialects and to Protestantism.

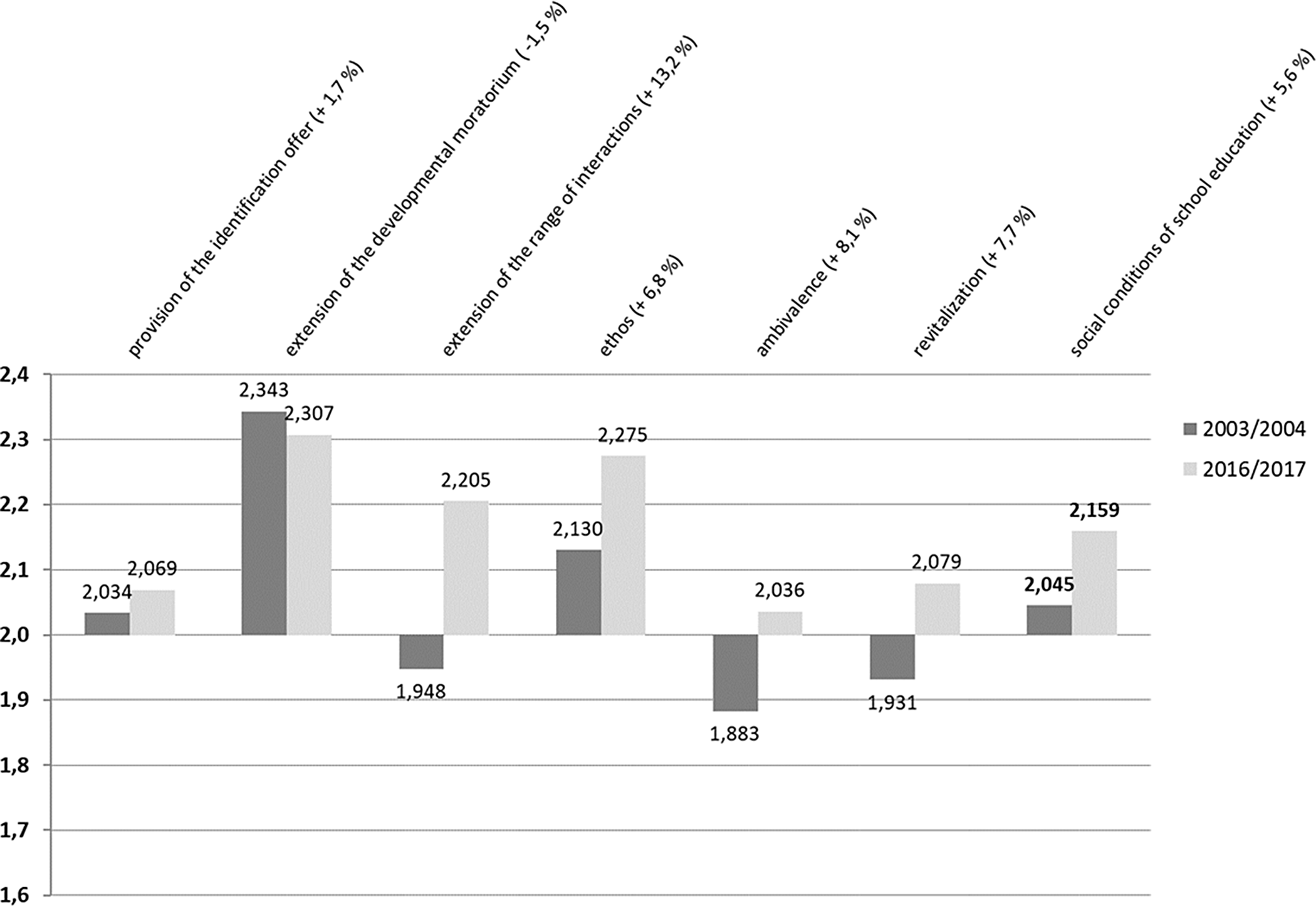

The selected and empirically verified tasks – as the research results have shown – prove to be universal for Polish secondary schools at two points in time. The average score for the completion of individual tasks was graded on a scale of 1 to 3 (1 – false; 2 – I don’t know; 3 – true) and has an average value above 2.0 (average 2.0 was considered the threshold for the completion of the tasks).Footnote 3

Research conducted in 2003/2004 showed that the secondary school carried out three of its six tasks. It offered real possibilities of extending the developmental moratorium, gave the basis for activity in situations where the principles of school life were clearly defined and justified – ethos; and it made it possible for individuals to identify with their own peer group, social group, school form, significant people and identification with the territory. Deficits of school education, i.e. its failure to fulfil its tasks in terms of shaping young people’s identity included the lack of situations/educational opportunities to: extend the range of interactions or experience ambivalence and revitalization.

In the opinion of youth surveyed in 2016/2017, the school performs all of its tasks.

Research conducted after an interval of 13 years revealed the greatest dynamics of change (see Figure 1) in the functioning of school and the fulfilment of its tasks in the areas of: extending the range of interactions (in 2003/2004

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 1.948; in 2016/2017

$$\overline x $$

= 1.948; in 2016/2017

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.205; change: 13.2%); ambivalence (in 2003/2004

$$\overline x $$

= 2.205; change: 13.2%); ambivalence (in 2003/2004

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 1.883; in 2016/2017

$$\overline x $$

= 1.883; in 2016/2017

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.036; change 8.1%); revitalization (in 2003/2004

$$\overline x $$

= 2.036; change 8.1%); revitalization (in 2003/2004

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 1.931; in 2016/2017

$$\overline x $$

= 1.931; in 2016/2017

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.079; change of 7.7%); ethos (in 2003/2004

$$\overline x $$

= 2.079; change of 7.7%); ethos (in 2003/2004

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.130; in 2016/2017

$$\overline x $$

= 2.130; in 2016/2017

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.275; change of 6.8%). The smallest change occurred in the area of providing the offers of identification (in 2003/2004

$$\overline x $$

= 2.275; change of 6.8%). The smallest change occurred in the area of providing the offers of identification (in 2003/2004

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.034; in 2016/2017

$$\overline x $$

= 2.034; in 2016/2017

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.069; change: 1.7%). A slight decline was noted in the extension of the developmental moratorium (in 2003/2004

$$\overline x $$

= 2.069; change: 1.7%). A slight decline was noted in the extension of the developmental moratorium (in 2003/2004

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.343; in 2016/2017

$$\overline x $$

= 2.343; in 2016/2017

![]() $$\overline x $$

= 2.307; change –1.5%).

$$\overline x $$

= 2.307; change –1.5%).

Figure 1. Tasks performed by schools in the school year 2003/2004 and 2016/2017 – the state and dynamics of change.

Source: own work

The highest dynamics (increase by 13.2%) was recorded in the area of extending the range of interactions, which in 2003/2004 was marked by a deficit. Over time, opportunities for youth to contact other people have increased, e.g. through social media, which are conducive to creating so-called horizontal friendships, an extended network of superficial, shallow relationships that do not require time, effort, attention or commitment (Gergen Reference Gergen, Katz and Aakhus2002, 227–241). The teacher–student relationship has changed for the better, and student subjectivity has increased (see Szczurek-Boruta Reference Szczurek-Boruta2007, Reference Szczurek-Boruta2019).

Against the background of the many tasks of schools, I regard ambivalence as a normal fact, a state of ambiguity, a specific task that the contemporary school is doing better and better at (an increase of 8.1% compared with the results of the survey in the school year 2003/2004). At the same time, school is not about deliberately generating ambiguous situations, but about using existing states that result from the structure of social relations and which underpin the behaviour of teachers and students. Both subjects (teacher, student) are aware of the ambivalence occurring at school, learn to live with ambivalence, and learn how to use divalent situations to serve their development.

School is part of a greater social system. Social life has power over adolescent individuals, repeatedly forcing them to behave in a manner that is characteristic of children. This power also lies in the fact that it pushes (reduces) individuals down to a lower development level, making them face the problem of revitalization (an increase of 7.7% compared with the research obtained in the school year 2003/2004), not just recreating in oneself the desire to live, but to recover a number of these vital forces (through independence, spontaneity and readiness to take initiative – the ability to stake one’s own professionalism, the ability to be faithful to ideals) that constitute the basic resources of human energy. School education creates opportunities and conditions for developing the individual’s ability to change the world, restore the desire to live and rebuild vitality.

The school attaches significance to ethos (an increase of 6.8% compared with the results obtained in the school year 2003/2004). Ethos means a set of values, norms and patterns of behaviour adopted by a given group of people, a constant manner of behaviour, attitudes to other people. It sometimes is tantamount to the general culture, the current lifestyle and custom. School contributes to the adolescents’ developing the ability to meet their obligations, show loyalty to a specific set of values, and stability in friendships.

Young people’s vital issue of identity is related to the quality of the identification offer which they encounter and which is available at the moment of entrance into the adult world. The identification process is the most important psychological aspect of culture, a bridge connecting culture and personality. Parents remain invariably important role models, objects of identification and persons who inspire respect in young people by their behaviour and manners (63%). The identification offer is also provided by people associated with broadly understood high and popular culture (music idols 39%; actors 32%). Culture propagated by the media is a creator and determinant of fashion: outer appearance, lifestyle, tastes, and ways of spending free time.

The secondary school extends the developmental moratorium, prepares for general education and for higher studies, postpones the decision to take up employment. Subsequent educational reforms in Poland sanctioned forms of extended school education, thus allowing young people to wait through periods of ambiguity, offering opportunities for development and better preparation for functioning in society.

The overall level of school fulfilling its tasks is not impressive. However, the 5.6% increase noted over the course of 13 years allows for a dose of optimism when thinking about the slow changes taking place within school.

The results of research carried out at two points in time revealed a relationship between the social conditions of school education and the identity of young people (in the school year 2003/2004 r = 0.682; p < 0.001,Footnote 4 moderate relationship); in the school year 2016/2017 r = 0.73757, p = 0.000, high correlation, significant relationship). Identity and the conditions for its formation are inseparable.

In analysing the results obtained, it is also necessary to take into account the changes in the structure of education, educational concepts, curriculums and assessment systems that have taken place. Over the period of the 13 years, education was reformed several times.

The group studied in the school year 2003/2004, representatives of generation Y, are graduates of an eight-year primary school and students of a four-year secondary school/five-year technical college. They undertook compulsory education in accordance with the Act on the education system of 1991 and its subsequent amendments as well as the applicable regulations regarding the core curriculum. Generation Y participated in the educational system reform postulated since 1989 (democratization of school life, programme changes, increases of school autonomy, and reduction of the controlling role of the pedagogical supervision; up to 1996, schools had been gradually transferred to communes and these adjusted the operation of existing primary schools to the requirements of the new school system and created junior secondary schools).

In the school year 2016/2017, the study covered representatives of generation Z – graduates of a six-year primary school, a three-year junior secondary school; general secondary school students (licea), vocational secondary school students (vocational training schools, technical colleges). Generation Z was covered by subsequent educational reforms. On 1 September 2012, the Act of 19 August 2011 amending the Act on the education system and some other acts came into force (Journal of Laws 2011, No. 205, item 1206), which by 1 September 2014 closed down three-year profiled secondary schools, two-year supplementary general secondary schools and three-year supplementary technical colleges accompanied by changes in the core curricula.

The changes described above did not have an impact on the formation of identity by young people. The effect of school activity (personality effect) did not change within 13 years.

Identity formation is a process strongly embedded in social, cultural, political and economic contexts (this interconnection was observed by Erikson and Havighurst).

School is an element of a broader social system, its activity is deeply embedded in the social, cultural and territorial context. These inseparable and dynamic systems largely determine the shape of youth’s identity, with due regard to the individual and their activity.

The functions of the school are determined from the outside by various factors operating in society. These include: culture and national culture demanding cultural continuity, cultural development and the creation of equal opportunities for all social groups in this respect; ideology, worldview and the system of moral norms and customs regarding human coexistence; and economic potential, which profiles education at the general level as well as in individual schools to meet the economic needs of the region and country.

Without a doubt, the educational reforms (curricular, administrative and financial ones) have resulted in an increase in the significance of school education and of school as a social institution, which has become an object of both common attention and criticism. The implemented reforms pertained to the outer aspects of school functioning. Not much has changed inside, in its inner functioning. Moreover, the changes take place slowly and their effects should be still awaited.

4. Conclusions

I have described several important tasks present in the field of education. They reflect the multidimensionality and complexity of matters determining the processes of upbringing, education and caregiving occurring in schools, and their effects.

For centuries, school has been accompanied by a belief that it has a very special role and place in society. It is supposed to help young people to manage their individual development and make intelligent life choices, it is intended to promote personality development and to help the formation of an individual’s unique identity.

Depending on the socio-cultural and economic conditions, the time when the education process takes place and the pedagogical concepts adopted, the importance of individual functions or sets of functions is highlighted.

The functioning of educational institutions is influenced by society, it reflects the principles, culture, internal divisions and crises existing in this society.

The degree to which a school performs its tasks is determined by the system in which the school operates. Schools invariably reproduce the social order, they focus on the performance of the socializing function and on the transmission of values. There are many indications that they are increasingly better at fulfilling the emancipation function. A special role in the Polish education system is played by: cultural capital (cultural goods, educational qualifications) and its transmission, and social capital (social networks) (an in-depth analysis of selected functions of educational systems is presented by Pierre Bourdieu in his reproduction concept).

The power of transmission of the Silesia cultural capital is invariably significant. The society is attached to the family, to traditional values and values associated with Christianity (especially to the customs of Christian holidays). It attaches a huge role to the nation (the awareness of harm suffered, a special mission in the world) and place of life – Silesia as a region. These well-established patterns and stereotypes – with a strong emotional background – are passed down from generation to generation.

School participates in this process and fulfils the integrating function. Educational institutions were founded to prepare members of the society to maintain the continuity of its existence and identity, and for keeping the pace of development that enables coexistence with other societies.

School enhances the forming of young people’s identity. It does this by passing on to them the appropriate elements of collective experience, which have been selected in compliance with developmental needs, and the components of symbolic culture – school implants socially desired behaviour patterns into young people.

For the young, school education is the first – and probably the most decisive for their future – contact with such an institution, and the type of experiences shaped in this way consolidates attitudes, of which the social usefulness will be tested in their mature lives.

The identified, described and empirically verified tasks of a school create a specific map of educational activities, which can be successfully used as a matrix to describe and interpret what is happening at school. It can be seen as a pattern (profile) of the social conditions of school education, which remains unchanged, with occasional shifts of emphasis from one element to another.

The research conducted and its results have provided a language and concepts with which we can penetrate deeper into the reality of the school and the social reality in which the school operates.

Making changes to the way the school works is a long-term process. The results of studies carried out at an interval of 13 years show a slight change in the degree of the school’s performance of its tasks (change 5.6%). It is not possible to immediately obtain a new, better and modern product. School has its operating logic, with staff qualifications and habits, established patterns of activity, and its kind of dependence on the external environment. Even a highly adaptive corporation needs ample time to carry out change. This does not depreciate the usefulness of school and education as tools for implementing change. It only calls for the realization that this is a long-term process, and school often remains isolated in its activities, even though it is a part of a broader system.

Youth research allows for thinking about this group in the category of ‘socially formative force’, which is able to join – as the Mannheim (Reference Mannheim1944) tradition puts it – in the current of social transformations and give the youth a character and direction resulting from generational traits.

Research on identity viewed through the lens of developmental tasks is research on the achievement of an individual’s own goals and research on the programme of activities in the pedagogical sphere. This programme cannot be conducted in isolation from the socio-cultural context in which pedagogical activities take place. In describing its characteristics, account must be taken of continuity, which refers to the links between functioning in earlier and later phases; the stability of behaviour patterns (which are automatized), and the stability of forms of behaviour manifestation, and the processes of culturalization and socialization responsible for the content of cultural identity and its change.

Two processes are key in the identity formation process: exploratory and decision-making processes. Exploration is a process in which an active individual seeks to solve problems related to the choice of goals, values and roles. Commitment means making a choice and constitutes a solution to a crisis.

On the one hand, educational activities need a broader range of offers, enabling students to undertake exploration, and enhance and verify their competences. On the other, educators need to encourage young people to make choices, to take decisions and experience their consequences, thus creating opportunities for young people to learn how to deal with the consequences of their own decisions.

While carrying out its educational tasks, a school cannot remain alone in its activities. Its educational successes are related to and largely dependent on the knowledge of the environment in which students live and whether the school acquires this environment as a partner in the process of education.

About the Author

Alina Szczurek-Boruta is a Professor at the University of Silesia in Katowice. Her research interests focus on multiculturalism and interculturalism, intercultural education, a sense of reflective identity and educational support for young adults, early school education, social pedagogy and the pedagogy of youth. She is the author of six monographs, co-editor of 15 monographs in the series Edukacja Międzykulturowa (Multicultural Education) and five in the series Pedagogika Społeczna (Social Pedagogy), and Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the journal Edukacja Międzykulturowa (Multicultural Education).