Introduction

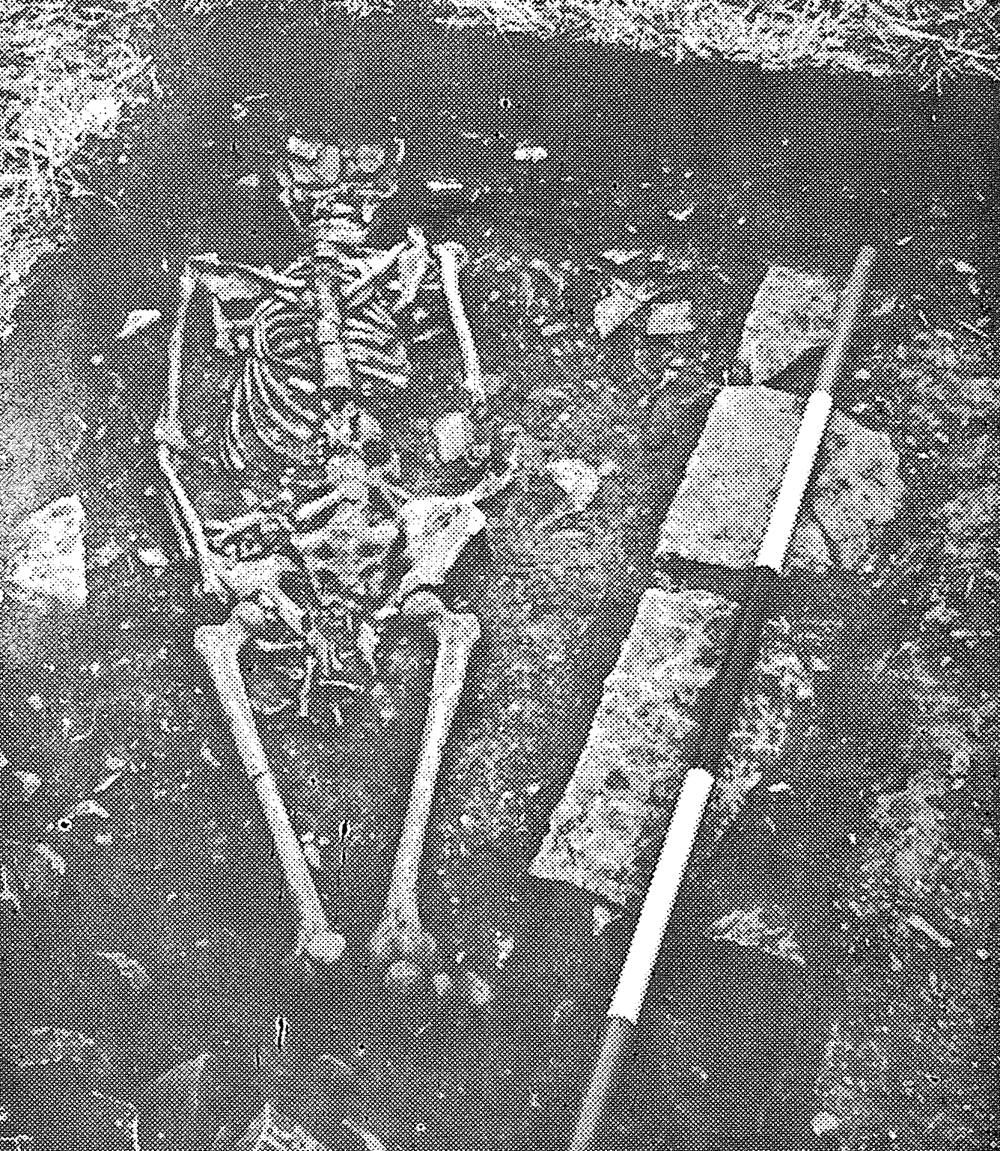

Rural communities in the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire experienced widespread transformation during Late Antiquity. This shift is clear in the development of new productive practices and habitational styles in Roman villas between the third and fifth centuries ad, a topic repeatedly addressed in the literature of the last few decades (e.g. Van Ossel, Reference Van Ossel1992; Chavarría, Reference Chavarría and Christie2004; Dodd, Reference Dodd2014, Reference Dodd2019). Despite this, overviews have lacked a data-driven approach to specific elements of this transition, especially in the funerary sphere and more specifically among the so-called ‘transitional burials’ at villa complexes. The burials under investigation here have generally been labelled as ‘transitional’ in that they are between the superficially ‘neat’ rural cemeteries of the Middle Roman period (Ferdière, Reference Ferdière1993; Hatton, Reference Hatton1999: 160–180; Kießling, Reference Kießling2008) and the later cemeteries arranged in rows of graves (the so-called Reihengräberzivilisation; Halsall, Reference Halsall1995: 9–13). Transitional burials have been considered ‘secondary’ in that they use features that were not originally designed for mortuary purposes. These burials differ from more ‘formal’ Late Antique cemeteries, both urban (e.g. Tongres in Belgium [Lesenne, Reference Lesenne1975: 81–86] and Poundbury in south-west Britain [Farwell & Molleson, Reference Farwell and Molleson1993]) and rural (e.g. Bradley Hill in south-west Britain: Leech, Reference Leech1981), in that they are characterized by a haphazard approach to inhumation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A ‘transitional burial’ in a villa context: inhumation in the east building at Ilchester Mead (from Hayward, Reference Hayward1982: fig. 21). By permission of Toucan Press.

Early Investigations

A long tradition of explanation is attached to transitional burials at Roman villas and the wider transformation or abandonment of such rural establishments. These aspects were used to support the ‘Gibbonist’ tradition (Lewit, Reference Lewit2001), which painted a picture of a declining empire (for general approaches, see Rémondon, Reference Rémondon1964, 71; Pignoil, Reference Pignoil1972; Gorges, Reference Gorges1979: 43–45). The narrative of ‘Decline and Fall’ was rooted in the literary sources, with archaeology playing a supporting role in painting a pessimistic account of Late Antiquity. For the villa landscape, its archaeology was used to highlight the destructive nature of Barbarian invasions (Grenier, Reference Grenier1934: 890–900; Wightman, Reference Wightman1985: 219–22) and to stress the end of the socio-economic norms of the Classical world.

The wider transformation of villa sites, including transitional burials, was addressed with a biased language: phrases such as ‘type d’ habitat précaire’ (a phrase for poorly constructed occupation; Lewit, Reference Lewit, Brogiolo, Chavarría and Valenti2005: 254; see also Mattingly, Reference Mattingly2007: 534) were used to describe archaeological features that appeared to reuse or damage earlier ‘Romanized’ elements. In English, the term ‘squatter occupation’ typically covers all of these. Squatter occupation was dismissed as an insignificant phase before the eventual abandonment of sites, or simply attributed to the ‘Germanic’ reuse of sites. This has led to serious deficits in our understanding of transformation at villa sites in Late Antiquity and the early medieval period (Storrie, Reference Storrie1908; Whiting, Reference Whiting1941).

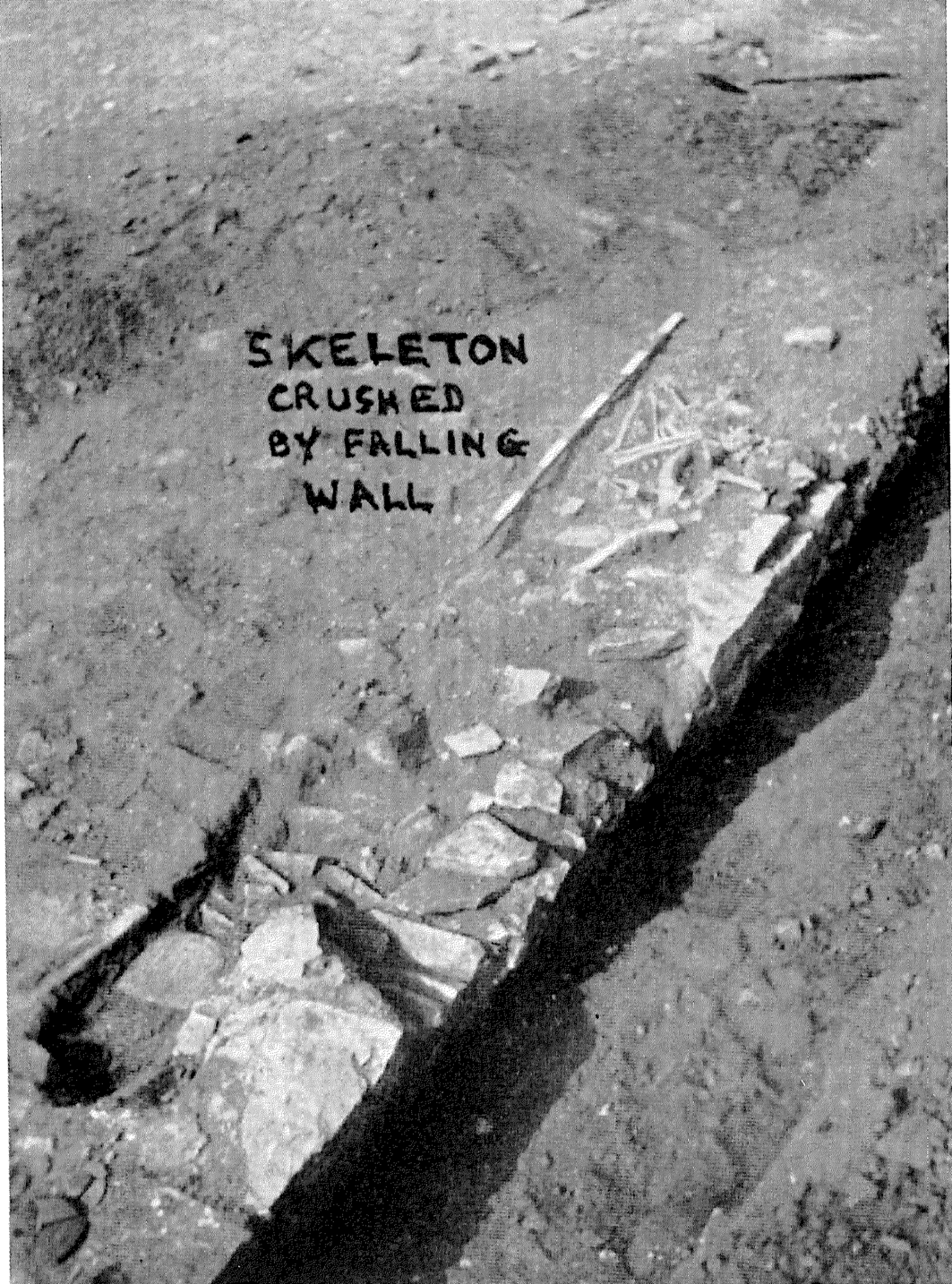

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the reuse of villas for funerary activities. The early investigation of transitional burials was highly fragmented by national-linguistic boundaries, although the analysis of the graves developed within the same broad framework. Specific explanations were repeatedly employed to describe and explain away the presence of Late Antique burials at villa sites (Figure 2), with implausible narratives deployed in individual cases (Oswald, Reference Oswald1937: 158–60):

‘How did the skeleton on the wall come there? The adjoining rooms and all the levels of this period bore traces of a fierce fire. It is perhaps permissible to suggest that these people were trying to escape from the burning building and that as the man on the wall passed over the threshold of the door the lintel collapsed on top of him, crushing the body into the distorted condition in which it was found. It is also possible that the other two people met their death in a collapse of the outer wall; certainly the skeleton of 2 was covered by wall stones, and at this point the foundation of the wall had subsided sideways in a northerly direction.’

Figure 2. Example of a ‘specific explanation’ of a Late Antique transitional burial at the Norton Disney villa (from Oswald, Reference Oswald1937: 157, pl. XLIII). By permission of Cambridge University Press and the Society of Antiquaries of London.

The use of ‘specific explanations’ has resulted in case-by-case study of transitional burials with individuals considered as everything from the victims of murder (Boon, Reference Boon1950: 18, Reference Boon1993: 78–80) to looters who improbably crawled into the ruins of a Roman town at Kingscote in western Britain to expire (Swain, Reference Swain1976: 21). At Brislington (Bristol), the interpretative options for three burials in a well is piracy, war, or suffocation in the fire which destroyed the site in the second half of the fourth century (Barker, Reference Barker1901: 289–90). In northern Gaul, the development of a ‘specific explanation’ was influenced by the identification of an occupation hiatus in the late third century ad.

Nineteenth-century investigation established a phase of abandonment and presumed destruction of a vast number of sites in Germania Inferior and Belgica (Grenier, Reference Grenier1934: 890–900), and destruction horizons and abandonment phases were linked to the breakdown of Roman control during the third-century crisis (De Maeyer, Reference De Maeyer1937: 290–95). Following the foundation of the German Reichs-Limeskommission and its subsequent excavations along the limes (Roman-Germanic frontier) between 1894 and 1900, this was explicitly linked to a fall of the limes, which stated that the Romans abandoned the Rhine in ad 259/260 (see Heeren, Reference Heeren2016: 185–88). It was assumed that the collapse of the limes allowed subsequent Barbarian incursions across the Rhine which destroyed or forced the abandonment of most of the villas in Germania Secunda and Belgica. Limited Late Antique occupation at sites in Germania Secunda was explained as involving Barbarian groups unable to comprehend the correct use of Romanized architectural elements (Joerres, Reference Joerres1886: 92–93). Transitional burials were an important part of this interpretation, especially those without defined features. Such burials were linked to Germanic raiding and it was widely assumed that haphazard burials in villas were the victims of the raiders (Schuermans, Reference Schuermans1867: 246).

Recent Approaches

From the 1970s onwards, it has become increasingly rare to evaluate transitional burials in the terms described above. Narratives of ‘squatter’ occupation were re-examined, and more nuanced narratives of ‘villa transformation’ were developed (Petts, Reference Petts and Meadows1997: 102–03; Christie, Reference Christie and Christie2004: 8–27). These new narratives focused on the economic basis of rural transformation (Lewit, Reference Lewit1991; Van Ossel & Ouzoulias, Reference Van Ossel and Ouzoulias2000) and emphasized the transformative nature of Late Antiquity society (Petts, Reference Petts and Meadows1997; Lewit, Reference Lewit2003, Reference Lewit, Brogiolo, Chavarría and Valenti2005; Chavarría, Reference Chavarría and Christie2004, Reference Chavarría2007). This development went hand-in-hand with the changing nature of the academic consensus, which increasingly stressed that the rejection of Classical traditions cannot be equated with socio-economic decline without resorting to overly simplistic models (e.g. Esmonde-Cleary, Reference Esmonde-Cleary1989; Van Ossel, Reference Van Ossel1992; Gerrard Reference Gerrard2013).

Within mortuary archaeology, new evidence has prompted a shift in our perception of cemeteries in Late Antiquity. Large Late Antique cemeteries have undergone further analysis (e.g. in northern Gaul: Brulet, Reference Brulet1990) whilst scholarship has begun to focus on the ritual and meaning of burials (Ripoll & Acre, Reference Ripoll, Arce, Brogiolo, Gauthier and Christie2000: 88–94; Chavarría, Reference Chavarría, Blasco and Christie2018) and move towards a more rigorous analysis of burials in the Late Roman period (Gerrard, Reference Gerrard2015). Although the theoretical framework has changed, and the academic consensus has moved away from a simplistic model of ‘Decline and Fall’, there has been little analysis of transitional burials at villa sites and an almost tacit acceptance of these explanations for transitional burials in villa sites. The critical investigation that exists (e.g. Morris, Reference Morris1992; Scott, Reference Scott1999, Reference Scott2018) has been dwarfed by the lack of large-scale analysis. Instead, modern scholarship has moved to placing these burials within the broader framework provided by the Christianization of the landscape (Percival, Reference Percival, Elton and Drinkwater1992; Cantino Wataghin, Reference Cantino Wataghin1999; Ripoll & Acre, Reference Ripoll, Arce, Brogiolo, Gauthier and Christie2000: 74–86; Lewit, Reference Lewit2003: 262–63), viewing decaying or abandoned villas as focal points within the wider countryside. The evidence behind these assumptions is either non-existent or has been ‘cherry-picked’ from across a variety of Roman provinces with increasingly divergent settlement trajectories.

The Dataset

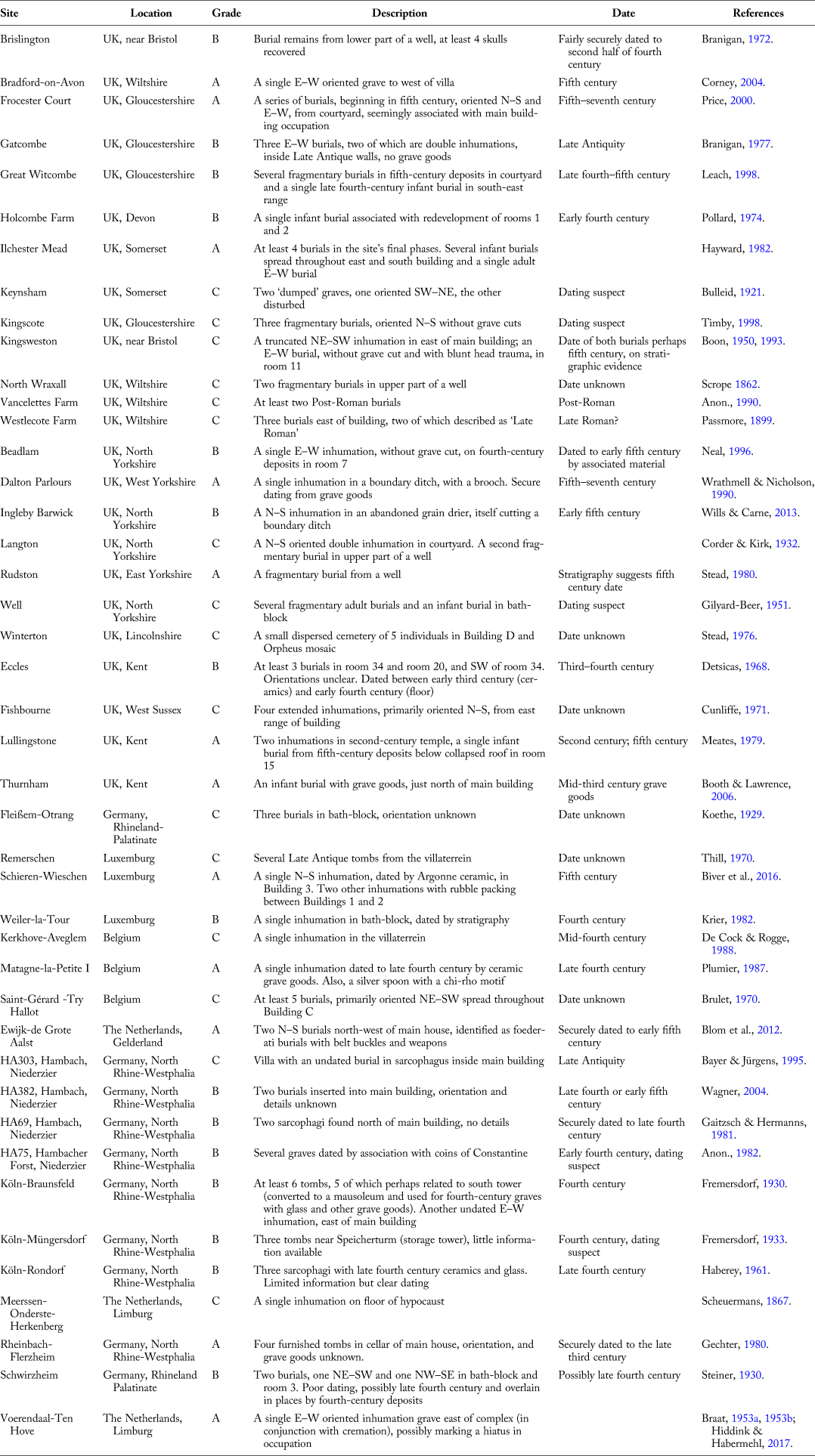

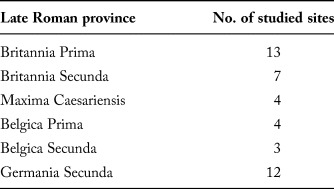

The dataset in this study consists of a regionally representative sample of forty-three villa sites with evidence of transitional burials (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1). Four distinct regions of the north-western provinces were chosen to provide diverse microregional studies in socio-economically different regions, capable of interacting with each other on a statistical level. These sites are unequally spread across Britannia, Belgica, and the Germanic provinces (Table 2).

Table 1. Site list. Grades refer to the reliability of the data, A being the most reliable.

Table 2. Breakdown of sites by Late Roman province.

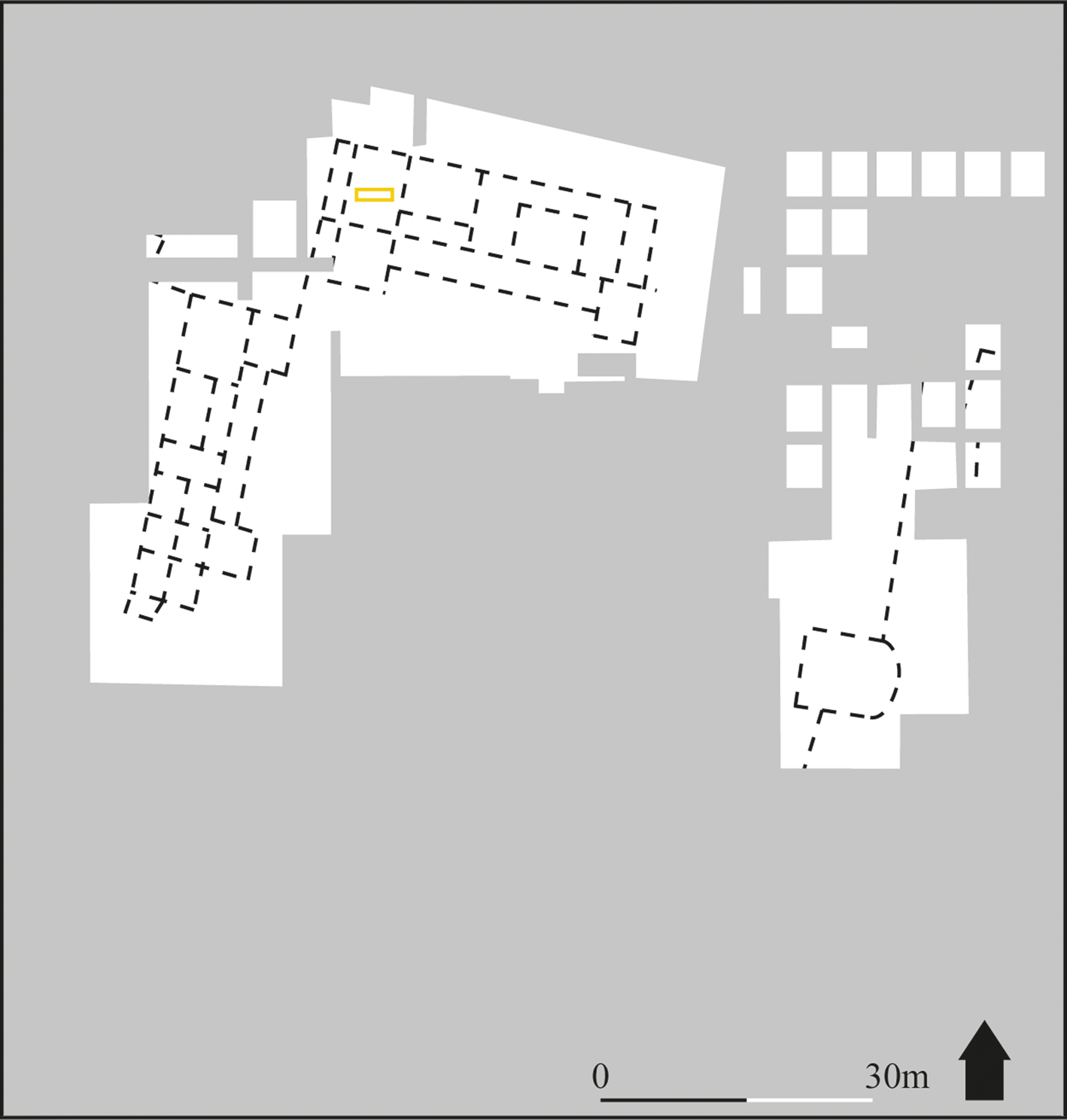

The transitional burials were defined along relatively loose parameters. The burials are identified as graves superimposed on features that were not originally designed for funerary purposes. This includes main buildings, agricultural buildings, and courtyard spaces or compounds around villa complexes. These inhumation burials, sometimes termed ‘secondary burials’, are morphologically varied; but we can often observe a link between the position of a grave and walls, pavements, or courtyard alignments of the villa complex (Figure 3). This definition does not include larger sites which could be interpreted as longer-term cemeteries, for example at Llantwit Major in Wales (Storrie, Reference Storrie1908) or those which have been identified as ‘Germanic’, for example, Rosmeer-Dieperstraat in Belgium (De Boe & Van Impe, Reference De Boe and Van Imp1979).

Figure 3. Plan of the Roman villa at Beadlam with a transitional burial of an adult female (in yellow) on a mosaic pavement from phase 4 (sub-Roman) (Dodd, adapted from Neal, Reference Neal1996: fig. 1).

Spatially, this study has limited the collection of data to the villaterrein. This Dutch word has no precise English equivalent but is a useful moniker. Generally, it refers to the area of a villa complex, including courtyards and open spaces as well as residential and productive zones and this study will use the term in this form. As for abandonment and transformation, these are two important linked terms used here. Traditionally viewed as a linear process (Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1987: 89), abandonment consists of a series of interlinked activities that defy simple categorization (Cameron & Tomka, Reference Cameron and Tonka1993; Stanton & Magnoni, Reference Stanton and Magnoni2008: 6–9). Here, abandonment is viewed as an ongoing process, with activities such as stone-robbing, partial reuse and mortuary activity loosely grouped together as ‘post-abandonment processes’. Mortuary activity, other than infant burial (see Millett & Gowland, Reference Millett and Gowland2015) is assumed in this study to have taken place in areas of villa sites that were not being used for other purposes.

The primary basis for the data (Dodd, Reference Dodd2014) has been supplemented by further collection from other gazetteers (De Maeyer, Reference De Maeyer1937; Scott, Reference Scott1993), using selection criteria designed to improve the quality of the dataset. Survey data were excluded and the selection limited to sites with at least one excavated building. Many small-scale commercial excavations of villa sites, often available through the French INRAP and British ADS repositories, have been left out because they were not excavated to a point at which contextual information about their later phases could be examined in detail. This leaves some areas under-represented, such as Belgica Secunda, where aerial photography has historically been the primary driver for villa identification (Agache, Reference Agache1978). Once the sites were selected, excluding sites unavailable for analysis despite large-scale excavations, individual site reports were used to select burial data. The distribution of the sites selected is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Distribution of transitional burials at villa sites in the study region.

The chronology of these burials is complicated. Traditional scholarship often attributed transitional burials to periods of historical upheaval, for example, the late fourth and early fifth century in Britannia and the late third or early fourth century in Germania Secunda. This has inevitably created biases in the dataset, for example, fourth-century burials dominate the corpus in Britannia. Recent radiocarbon dating of burials, however, indicates that burials spread over longer periods, especially in Britannia, where much of the work has been conducted (Gerrard, Reference Gerrard2015; Smith, Reference Smith, Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford and Lodwick2018). This chronological issue is further compounded by the lack of grave goods. Only a few burials, for example at Matagne-la-Petite in Belgium (Plumier, Reference Plumier1987), are closely datable. Most graves in this study are unfurnished and, therefore, difficult to identify. Chronologically, this problem presented a choice: either reject outright traditional identification and invalidate any statistical appreciation of the phenomenon or take burials at face value. Neither of these options was satisfactory, so a blend of the two was selected as viable. The data were graded according to their reliability (grades A, B, C, see Table 1), based on a close scrutiny of the site reports. This allows for normative judgements to be made and for burials to be reassessed on stratigraphic information, separating sites into those where dating is relatively secure and those where dating is suspect.

It is not the aim of this article to reassess the much-discussed meaning of the word ‘villa’ (see e.g. Percival, Reference Percival1976: 14–15; Willems, Reference Willems1981; Habermehl, Reference Habermehl2014: 17–18) but rather to examine elements of the Late Antique landscape. This study defines the villa as a rectangular, monumentalizing, stone-built, rural building displaying non-functional features that exhibit a degree of Romanized material culture. This approach has been repeatedly used to define the term archaeologically and is common to a variety of studies of Late Antique phases at villa complexes (Van Ossel, Reference Van Ossel1992: 39–44; Heimberg, Reference Heimberg2002–2003: 68–69; Chavarría, Reference Chavarría2007: 32–36).

The transitional burials consist mostly of individuals or small groups. Groups of four or more inhumations are rare in the dataset. These larger groups make up about 23 per cent of the dataset and are concentrated in Germania Secunda and Britannia (Table 3). Although the evidence consists of burials on villaterrein, it should be noted that this is not a villa-specific phenomenon. A variety of other rural settlements, including rural sanctuaries (see Derks & de Fraiture, Reference Derks and de Fraiture2015), also underwent a similar phase of funerary reuse.

Table 3. Number of sites by burial group size arranged by province.

Temporal Dimension

Traditionally, transitional burials have been identified as a Late Antique phenomenon, with the majority assumed to date to the late fourth century onwards. The Germanic provinces are the exception, with a period of activity in the late third century. These chronological approaches appear in the traditional literature, through the repeated use of terms such as ‘Sub-Roman’, as well as in modern approaches, which assume that the phenomenon developed towards the end of the Roman period as part of the breakdown of socio-cultural practices associated with the end of the Classical world (Lewit, Reference Lewit, Brogiolo, Chavarría and Valenti2005: 252–54).

The data laid out in Figure 5 show a spike in activity in the fourth century rather than a post-Roman peak, although radiocarbon dating may change this situation in future, if applied to the large ‘unknown’ variable. Three phases can be discerned: a third-century development phase geographically limited to certain provinces, a fourth-century period of intense use, and a slow decline in activity in the fifth century.

Figure 5. Chronological composition of the dataset, by Late Roman province (n = 43).

The emergence of the transitional burial phenomenon in the third century suggests that, in some regions, rural populations were burying in villa buildings, either as abandoned areas or as buildings in use. This indicates that it was part of a wider tradition of termination rituals (Esmonde-Cleary, Reference Esmonde-Cleary, Pearce, Millett and Struck2000; Pearce, Reference Pearce2013; Smith, Reference Smith, Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford and Lodwick2018: 234–38). The presence of infant burials (Millett & Gowland, Reference Millett and Gowland2015) as foundation markers is well-researched and, in most cases, differs from the traditions examined in this article. Repeated evidence from this dataset is suggestive of mortuary activity as the final activity in parts of sites or even across entire sites. Eccles in Kent (Detsicas, Reference Detsicas1968) is a clear example. The bath complex was decommissioned in the late third century and was marked by three crouched inhumations, dated to the fourth century by the flooring that sealed them. This is mirrored at Schieren-Wieschen in Luxemburg, where a fifth-century burial (Biver et al., Reference Biver, Stead and Polfer2016) was the last activity in Building 1.

The decrease in the number of burials in the fifth century is most noticeable. This contrasts with long-held views that transitional burials occurred after the formal end of Roman rule. Only the group of burials from Britannia Secunda shows a bias towards the fifth century. Primarily, transitional burials are a feature of the funerary landscape of the fourth century, which indicates two broadly similar trends. First, different attitudes towards the dead were developing across the north-western provinces amongst rural populations, perhaps as a harbinger of the same phenomenon in fifth-century urban centres (Bidwell, Reference Bidwell1979: 245–50; Bridger, Reference Bridger, Müller, Zieling and Schalles2008; Speed, Reference Speed2014: 101). Second, it suggests that villa buildings were still visible when the individuals were inhumed. This supports the notion that some of these burials were placed rather than ‘dumped’ into ruins. Many transitional burials were deliberately aligned with the orientation of buildings, for example at Winterton in Lincolnshire (Stead, Reference Stead1976: 49–50) and Fishbourne in Sussex (Cunliffe, Reference Cunliffe1971: 219).

Spatial Dimension

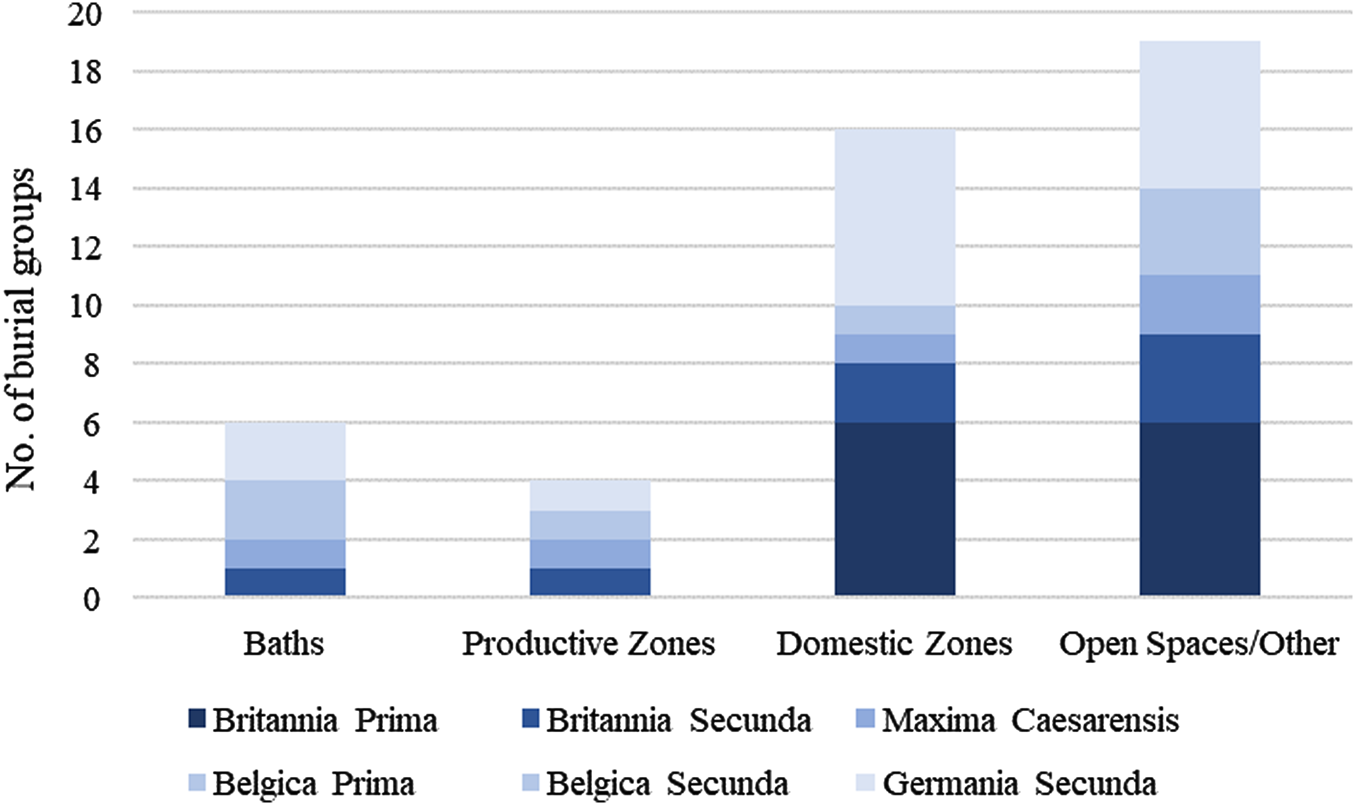

The assumption that high-status buildings, such as bathhouses, were focal points for transitional burials has been a recurrent topic in the literature (Percival, Reference Percival1976: 183–99; Lewit, Reference Lewit1991: 41–43, Reference Lewit, Brogiolo, Chavarría and Valenti2005: 256; Le Maho, Reference Le Maho, Fixot and Zadora-Rio1994, 12–13, 19–20). Our data (Figure 6) illustrate a different situation, being dominated by the use of open spaces with other zones less important. This is repeated in all regions, with burials primarily located in courtyards (Corder & Kirk, Reference Corder and Kirk1932: 59) or the villa's wider neighbourhood (Plumier, Reference Plumier1987: 146, figs. 2 & 3) rather than in high-status zones. Burials in the villaterrein represent a different trajectory but complemented by a preference for domestic zones when burials are interred in existing structures. Burials in bath complexes, contrary to circumstantial data collection, are not very frequent, although they are a widespread sub-set of mortuary practice across most of the north-western provinces. The lack of use of a site's productive areas for burial purposes is a notable divergence from other regions in the Late Roman West (Chavarría, Reference Chavarría2007: 134–37). This is not borne out in the data, where the overwhelming preference is for other areas. It may be that productive zones in north-western Europe experienced more activity in Late Antiquity and were, therefore, not considered suitable for funerary purposes.

Figure 6. Composition of the location of transitional burials, where data are available (n = 45).

The micro-spatial breakdown of transitional burials at villa sites raises questions about the division between burials in the wider villaterrein and burials inside domestic zones or bath complexes. Villas with an exterior funerary phase appear to have some occupation on site, for example at Ewijk-De Grote Aalst in the Netherlands, where burials are placed outside the inhabited zone in the early fifth century (Blom et al., Reference Blom, van der Feijst and Veldman2012: 275–83). This sharply contrasts with burials inside structures, where the individual building or villa site appears to have been abandoned, for example the abandoned Building C used as a cemetery at Try Hallot in Belgium (Brulet, Reference Brulet1970: 73, fig. 5). This can be tied to the widespread abandonment of sites across the region and is perhaps indicative of a phase of ‘termination rituals’ in which burials marked the end of occupation rather than the ‘specific explanations’ traditionally used to describe these graves. The shift from a clearly delimited boundary between occupied and funerary landscapes towards burials moving into villa buildings suggests a significant change in mortuary practices. This may point to a social pattern where there was little or no convention regulating the separation of the landscape of the living and dead and a new pattern of funerary expression developing in lieu of Romanized traditions. Burials marking the end of occupation at villa sits could conceivably have taken place at the same time as post-abandonment activities, such as stone recovery or the temporary use of abandoned sites.

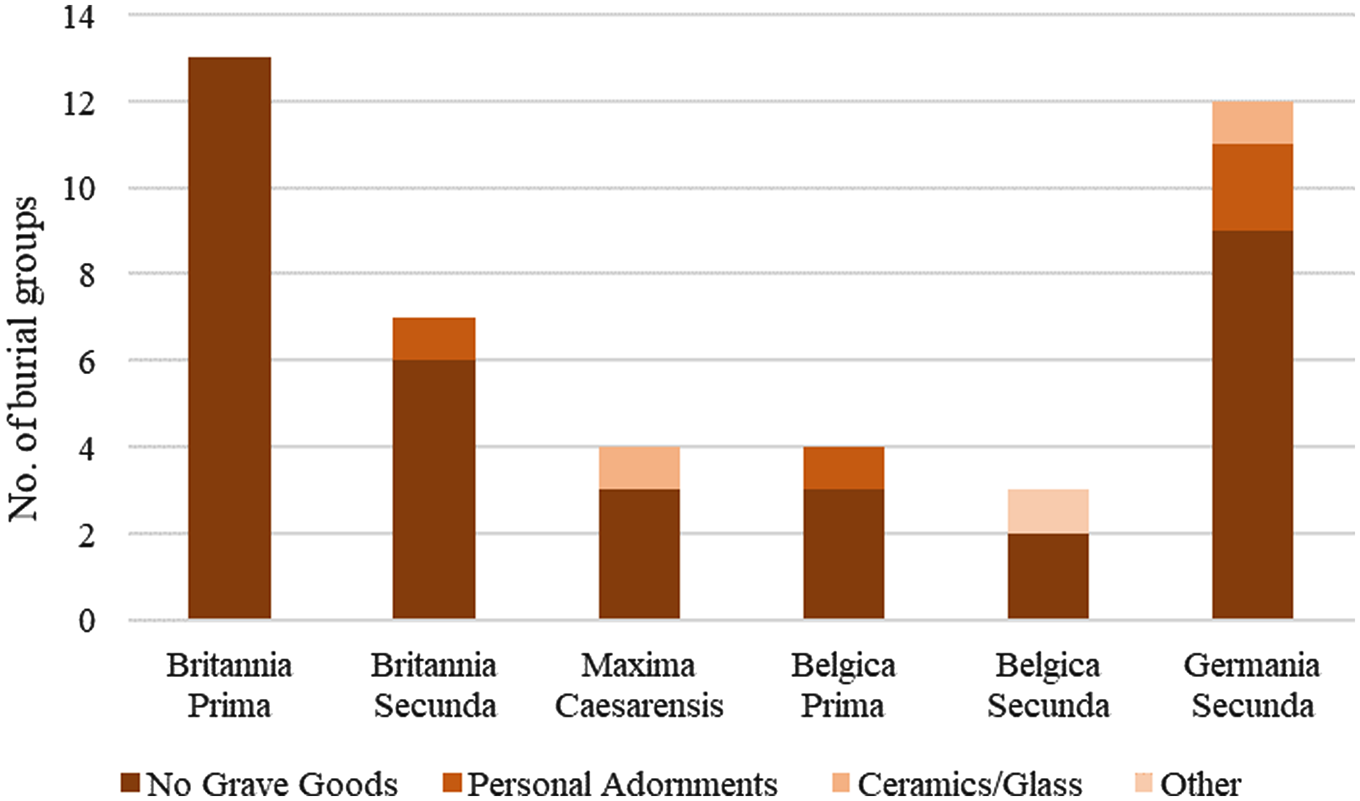

Grave Goods

Few burials show evidence of grave goods, with only 17.5 per cent of graves containing any (Figure 7). This fits the Late Antique tradition of unfurnished burials (Smith, Reference Smith, Smith, Allen, Brindle, Fulford and Lodwick2018: 265–68, fig. 6.48), and it is notable that most furnished burials date to the third century and seem to relate to earlier traditions (e.g. Thurnham in Kent: Booth & Lawrence, Reference Booth and Lawrence2006: 108–09). Where grave goods are present, there is significant diversity, albeit with a distinct lack of ceramic vessels. Personal adornments dominate and include rings (e.g. Köln-Braunsfeld: Fremersdorf, Reference Fremersdorf1930: 128–32), glass vessels (e.g. Köln-Rondorf: Haberey, Reference Haberey1961: 336–39), and military objects (e.g. Ewijk: Blom et al., Reference Blom, van der Feijst and Veldman2012: 27–283). In some cases, such as Köln-Braunsfeld and Gatcombe in Gloucestershire (Branigan, Reference Branigan1977: 65), there are indications that burials form part of a Christian tradition with overt religious motifs or burials oriented east–west.

Figure 7. Composition of the types of grave goods in transitional burials, by Late Roman province (n = 42).

Stylistic and cultural-historic analysis of individual graves and their associated artefacts has focused on the divide between unfurnished burials and the richer cemeteries of the Migration period and the creation of binary ‘Roman/Barbarian’ narratives (see Theuws, Reference Theuws, Roymans and Derks2009; Burmeister, Reference Burmeister2016). Traditionally, transitional burials were viewed as ‘Roman’ in origin because they were unfurnished or contained demonstrable ‘Roman’ grave goods. Scholarship has repeatedly placed them in the Late Antique mortuary tradition, despite a lack of chronological indicators (Percival, Reference Percival1976: 183–99).

Conclusions

The analysis presented here is by no means conclusive but serves to illustrate what can be achieved when evidence from different burials is examined as collectively rather than on a case-by-case basis. The key finding in this paper is the lack of disparity between Britannia and the continental provinces, suggesting they are not as divergent as has been thought (e.g. Gerrard, Reference Gerrard2013). The distribution of burials suggests that villa-using populations in Belgica, Germania Secunda, and Britannia had the same form of funerary expression over the course of Late Antiquity. This supra-regional approach to funerary expression may indicate that similar factors were influencing the development of the phenomenon across large regions, rather than limited socio-cultural trends. Despite transitional burials in villas being a widespread phenomenon, their time span is short. The evidence so far, although future radiocarbon dating could radically change this picture, suggests a peak of intensity in the fourth century and little use of villa sites for this purpose beyond the fifth century. The decline of transitional burials may point to new realities in the post-Roman fifth century and the appearance of new population groups in north-western Europe (Heeren, Reference Heeren, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015) not engaging in this form of mortuary expression. From the mid-fifth century onwards, larger cemeteries with hybridizing styles (Heeren & Roymans, Reference Heeren, Roymans, Kars, van Oosten, Roxburgh and Verhoeven2018), many with features identified as ‘Germanic’ (Halsall, Reference Halsall2009), replaced transitional burials as the primary form of funerary expression on villa sites in both Britannia and north-western Gaul.

Our data suggest that two separate traditions can be discerned: the use of the wider villa landscape for burial when the site was in occupation, and the use of abandoned (or partially abandoned) zones for termination rituals. The first is visible in the increasing spatial diversity of burials across the wider villaterrein, rather than in the clustered cemeteries of the Middle Roman period in continental Europe and rural cemeteries in Britannia. Although this appears to be a break from the past, it is a less dramatic rupture than would first appear. The Classical taboo between life and death was retained and clear divisions between operational structures and the funerary landscape maintained. The second tradition appears to act as a form of ‘termination ritual’ (Merrifield, Reference Merrifield1987), in which burials were used to seal off abandoned areas of a site; it is linked to similar uses of animal burials (King & Grande, Reference King, Grande, Henig, Soffe and Adcock2015: 9). Such ‘dumped’ burials, as they used to be interpreted, are present on a variety of sites, where burials act as the final activity overall or in certain sectors of sites. The phenomenon requires much more investigation: without further radiocarbon dating work, little more can be added.

The meaning of these ‘casual’ burials has long created interpretative problems in developing a ‘neat’ solution for the end of the villa landscape. Consequently, archaeologists instead developed specific explanations for individual burials. It seems likely that we merged two conflicting trends and assumed they represented the same phenomenon. Burials inside buildings were probably related to the termination rituals of entire sites or zones within them, with other buildings being given over to burial upon decommissioning. The alignment of many of these burials with the structures on site suggests that the deceased were not simply ‘dumped’ but carefully positioned to take advantage of the visible ruins. One notable aspect of this situation is that transitional funerary use of some buildings was concurrent with quarrying, including the reclamation of building material, illustrating the multiple trajectories that a site can follow after the end of its formal use. Burials in the wider villaterrein are a different phenomenon, highlighting the changing nature of Late Antique habitation within an occupied and productive landscape. There are significant differences compared to burials inside abandoned buildings, especially with respect to grave goods. Within this group, the Classical taboo (i.e. separation of the realm of the dead from that of the living) was maintained; but the apparent lack of clearly defined cemeteries on the sites’ edges suggests that this was no longer strictly applied.

These patterns indicate that the villa landscapes of the north-western provinces underwent large-scale social change, reflected in burial practices and the shifting priorities of rural populations in the north-western provinces during Late Antiquity. They hint at new socio-economic conditions, which encouraged the abandonment and termination of villa settlements across the region and began to erode the important separation between life and death.