Introduction

Bipolar disorders are a group of conditions that encompass pathological alterations in mood, activity, and biological rhythms. In addition to this, these disorders are associated with varying degrees of psychotic symptoms, loss of functioning, and neuropsychological impairments.Reference Aminoff, Hellvin, Lagerberg, Berg, Andreassen and Melle 1 The last decade has witnessed a surge of interest particularly in the latter: the neuropsychological correlates of this commonly occurring phenotype.

Neuropsychological dysfunction is a well-established finding in people with bipolar type I (BP-I), even in the euthymic state of the illness.Reference Doruk, Yazihan, Balikci, Erdem, Bolu and Ates 2 – Reference Santos, Aparicio and Bagney 5 Cognitive performance is an area of increasing interest in bipolar type II (BP-II), as recent studies have found that these patients also perform more poorly than healthy controls on neuropsychological tests.Reference Andersson, Barder, Hellvin, Lovdahl and Malt 6 – Reference Torrent, Martinez-Aran and Daban 9 A previous review published by Sole et alReference Sole, Bonnin and Torrent 8 suggested a possible subtle distinction in performance between BP-I and BP-II; however, they stated that more studies were needed in order to make any firm conclusions. Despite this, recent research has focused mainly on BP-I, partly due to researchers and clinicians attitudes toward BP-II, ie, recognizing the difficulty in differentiating BP-II from major depressive disorder (MDD) in those experiencing major depressive episodes (MDE). For example, 2 studies concluded that over 40% of bipolar disorders are misdiagnosed as MDD.Reference Angst, Azorin and Bowden 10 , Reference Ghaemi, Sachs, Chiou, Pandurangi and Goodwin 11

Even more challenging to diagnose accurately are subthreshold bipolar disorders (SBP), for example, bipolar not otherwise specified (BP-NOS) and those with mixed (ie, subthreshold hypomanic) features alongside their depressive episodes, which are most often misdiagnosed as MDD.

Current classifications have major limitations, and because of this, individuals are termed as “not otherwise specified” (BP-NOS). Similarly, the clinical entity termed MDD represents only the final, external manifestations of an enormously complex, multilevel, multifactorial process, and mood disorder research, particularly in the area of neuropsychological functioning, might benefit from stratifying these classifications into more homogenous dimensions of pathology. An alternative model is necessary to either complement or replace the traditional categorical approach. Recognizing the complexity of both uni/bipolarity and the limitations of current diagnostic systems should motivate researchers to work toward building alternative models for understanding these conditions.

Cognitive deficits in attention are part of the MDD current diagnostic criteria,Reference Goeldner, Ballard, Knoflach, Wichmann, Gatti and Umbricht 12 and deficits of attention and memory are often reported by patients suffering from this condition. However, there remains no agreement as to the nature and extent of dysfunction in depression, and the neuropsychological functioning of SBP, particularly in euthymic periods, has not yet been established.

Iverson et alReference Iverson, Brooks, Langenecker and Young 13 found that a subgroup of mood disorder patients had frank cognitive impairments, but that the majority were broadly cognitively normal. A larger proportion of patients with bipolar disorder (41.9%) than patients with depression (27.1–28.6%) met criteria for cognitive impairment in this study. Iverson and colleagues concluded that future research should determine if this identified subgroup has neuroanatomical, neurophysiological, and/or or neuroendocrine abnormalities. In addition, a meta-analysis revealed that euthymic MDD patients were characterized by significantly poorer cognitive functions; however the magnitude of observed deficits, with the exception of inhibitory control, were generally modest when late-onset cases were excluded.Reference Bora, Harrison, Yucel and Pantelis 14 Late-onset cases demonstrated significantly more pronounced deficits in verbal memory, speed of information processing, and some executive functions. Bora et alReference Bora, Harrison, Yucel and Pantelis 14 concluded that more research was needed, particularly in remitted psychotic and melancholic MDD and in SBP disorders.

The aim of this review, therefore, is to provide an update on neuropsychological dysfunction in BP-II, since the earlier review by Sole et alReference Sole, Bonnin and Torrent 8 and the meta-analysis by Bora et alReference Bora, Harrison, Yucel and Pantelis 14 , with the aim of confirming whether BP-II patients do indeed differ from or whether they share a similar cognitive profile to that of BP-I. We will then focus on the neuropsychology of subthreshold bipolar disorders; we present and review all studies relating to neuropsychological function in this phenotype. Utilizing our findings from this review, we will discuss the plausibility for an alternative dimensional approach to bipolar disorders and whether the current taxonomy, which partitions what may essentially be better understood as a spectrum into discrete disorders, is the most valid approach. Last, and in keeping with this dimensional model, the underlying bases for cognitive dysfunction need to be investigated, and we suggest recommendations for future research.

Methods

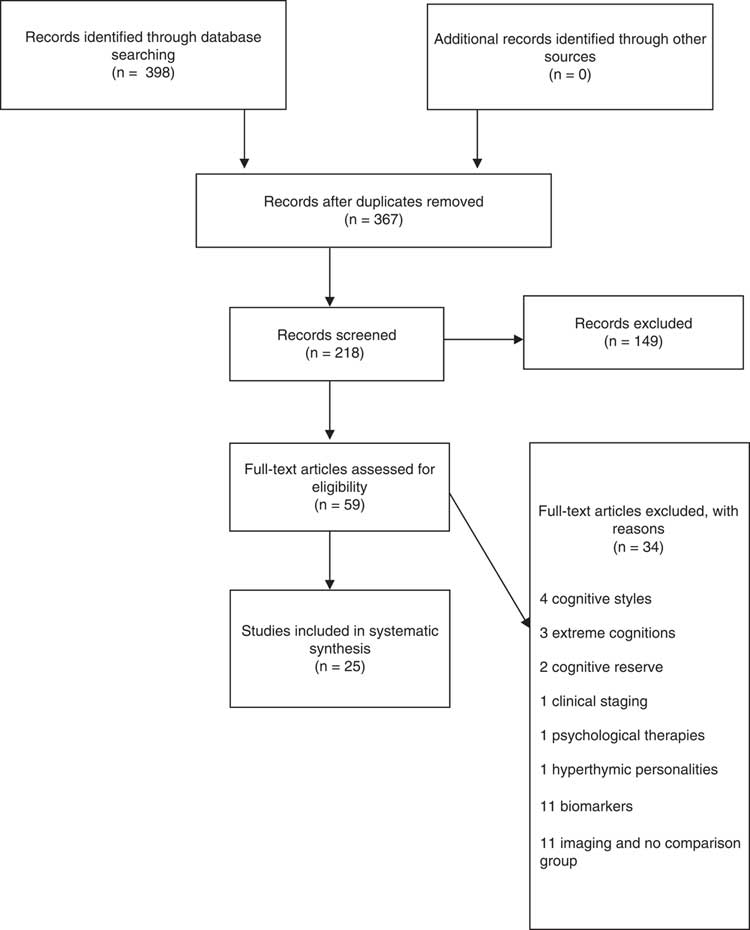

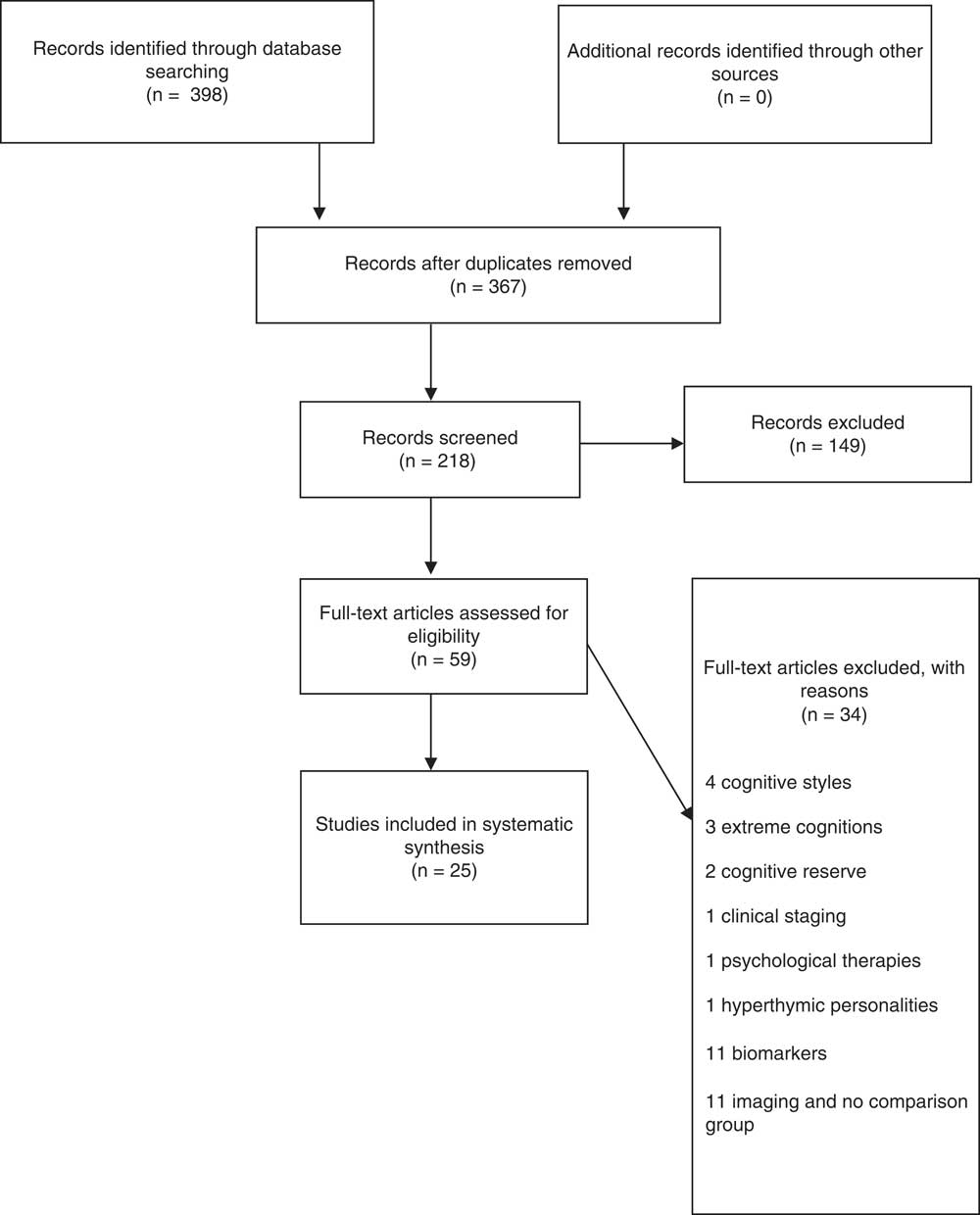

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Medline, PsycINFO, and The Cochrane Library was carried out in order to conduct a systematic review of the available literature on neurocognitive function in hypomanic bipolar disorders; 17 studies met eligibility criteria (see Figure 1). Articles were excluded if they did not fit the eligibility criteria, ie, they examined constructs such as cognitive styles, extreme cognitions, and hyperthymic personalities. Eligibility criteria were (a) studies that included a comparison group [psychiatric or healthy control (HC) group], cross-sectional case-control studies or normative data for standardized tests; (b) published through to January 2017; and (c) adult patients (aged 18–65). Only English-language articles published through to January 2017 were included in the present review, using the search terms “bipolar,” “bipolar II,” “sub-syndromal bipolar,” “subthreshold bipolar,” “bipolar spectrum,” “other related bipolar,” “not otherwise specified,” “DSM-5 mixed episodes specifier,” “cyclothymia,” and “cyclothymic disorder,” cross-referenced with “cognition,” “cognitive function,” “cognitive impairment,” “neuropsychological,” “neurocognitive,” “attention,” “memory,” “verbal memory,” and “executive function.”

Figure 1 Systematic search of cognition in BP II and SSBP.

Search-Term Selection

The above cognitive domains were specifically chosen as search terms by the authors, as they have been found to show large effect sizes in bipolar disorder research, across the spectrum.Reference Robinson, Thompson and Gallagher 15 See below for an outline of the current literature regarding each domain and the alterations involved, specifically in bipolar disorders.

Executive function

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the definition of executive function (EF), its components, and their neurobiological underpinnings. Despite these disagreements, an essential characteristic of EF is its capacity to coordinate cognition, behavior, and emotions and to direct an organism to establish goals. EF is a set of mental processes that helps connect past experience with present action. EF (ie, memory, planning, behavior) are all governed by the brain, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC and its related neural circuitry are critically involved in executing many of the components underlying executive function: “The PFC is the most evolved brain region—and sub serves our highest-order cognitive abilities. However, it is also the brain region that is most sensitive to the detrimental effects of stress exposure” (p. 1).Reference Arnsten 16 Executive function is also closely linked to emotional regulation,Reference Siddiqui, Chatterjee, Kumar, Siddiqui and Goyal 17 contributing to successful psychosocial functioning. According to Addis et al,Reference Addis, Hach and Tippett 18 even subtle changes in executive function may induce overgeneralization of the past or future events. See Table 1 for how executive function relates to bipolar disorders.

Table 1 Cognitive domains and alterations in mood disorders

Attention

Attention is a concept that includes a number of processes that work together and influence one another. These processes include working memory (which refers to the ability to keep a limited number of mental objects in awareness for a limited duration of time), vigilance (which is the capacity to identify a specific target among many other stimuli), freedom from distraction or interference, and the ability to split or to rapidly shift attention. Concentration is a term that refers to the ability to sustain attention over prolonged periods of time. There are many tests, with each of them assessing one of the previously mentioned processes. See Table 1 for how problems with attention relate to bipolar disorders.

Verbal learning and memory

Learning and memory occur over time and involve a number of different individual events, including attention and concentration, encoding (learning), and retrieving (the memory). These processes are distinct from one another but are also interrelated and interdependent. Verbal memory is a broad term used to refer to the memory of language in various forms. This type of memory has commonly been linked to the left side of the brain. Particularly, it is generally associated with the medial temporal lobe on the left side. This is not the case in all individuals, though, and some individuals who use both sides of the brain to access this type of memory have demonstrably better verbal memories. See Table 1 for evidence of verbal learning and memory impairments in bipolar disorders.

Visual spatial working memory

Visual spatial working memory maintains spatial and visual information, thus ensuring the formation and manipulation of mental images. These processes have been linked to the right hemisphere. Visuospatial working memory theory is used to interpret the cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar disorder, and deficits are associated with the condition.Reference Thompson, Hamilton and Gray 19 Working memory is postulated to be composed of a central executive control system that monitors 2 independent subsystems: a visuospatial sketchpad for spatial processing and a phonological loop for nonspatial, mainly verbal information.Reference Baddeley 20 , Reference Baddeley, Logie, Bressi, Della Sala and Spinnler 21 See Table 1 for evidence of how visual spatial working memory are affected in bipolar disorders.

Quality Assessment

Research reports were assessed by the authors using 7 criteria: selection bias, design, confounders, blinding, data collection, methods, and withdrawals and dropouts. The “Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies”Reference Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci 37 developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) is a tool for knowledge synthesis. This instrument, along with a user manual, provides a standardized means to assess study quality and develop recommendations for study findings. The quality appraisal tool was developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) as a discrete step within the systematic review process. Validity and reliability properties meet accepted standards. The scoring is divided into 3 categories, strong=3, moderate=2, weak=1 and a sum total of each for the overall score. The authors of this review contacted all authors of the studies, who were given an opportunity to agree or disagree with the rating. If discrepancies were found in the initial study rating, scores were updated based on evidence provided by authors, all of whom agreed to their individual ratings in Table 2.

Table 2 Quality assessment

Results

The systematic search yielded 59 articles, 17 of which are relevant for and included in this review. Table 3 summarizes the findings of all of the studies included in this review. Results will be described here based on sample size, cognitive task used, main findings, and limitations. First, we give a more detailed description of all of the cognitive tasks and domains used in each of these studies (Table 2), and then we present an in depth review of the most relevant domains (Table 3).

Table 3 Neuropsychological classifications of tests used in each study

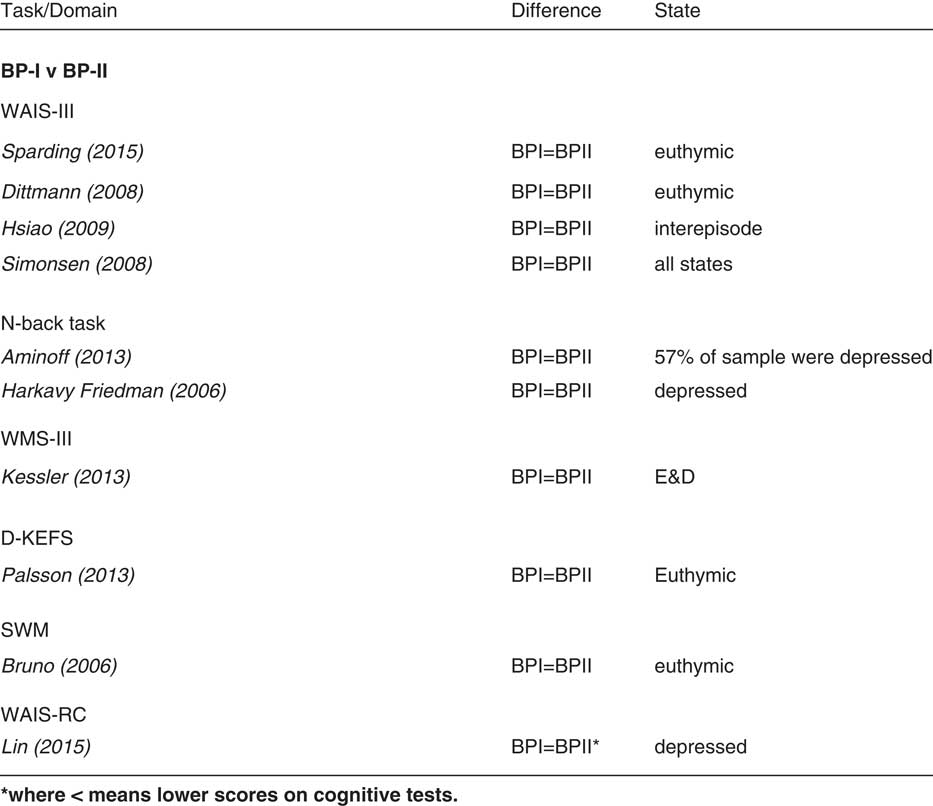

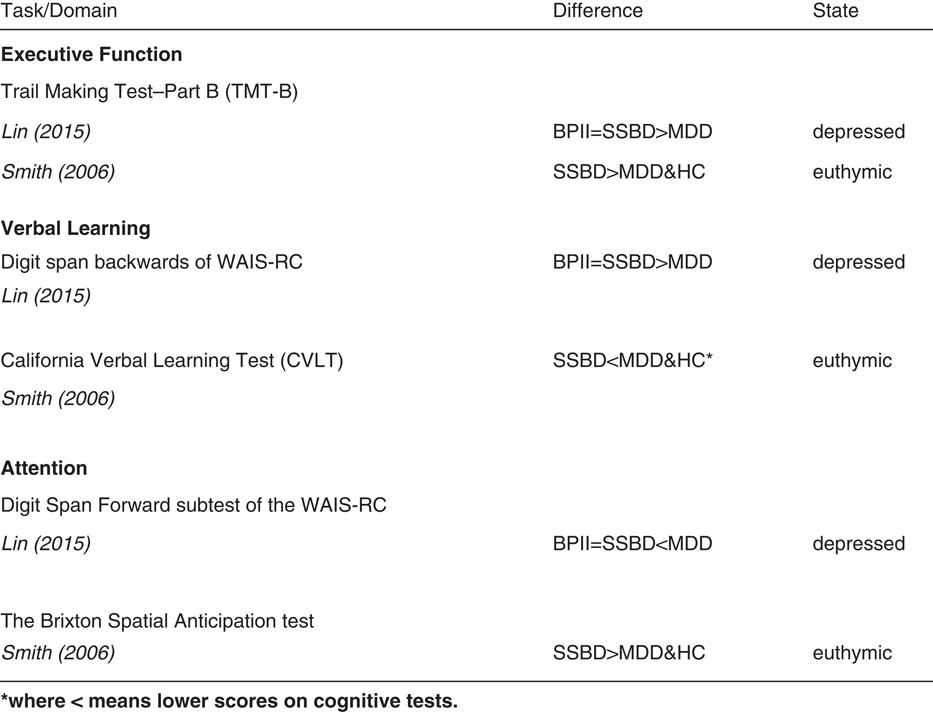

Next, we present accounts of each cognitive domain in the Figures 2–7 to give a more in depth review and clear answer as to whether (i) neurocognitive dysfunction in BP-II is similar to BP-I in each cognitive domain and (ii) whether these deficits exist in subsyndromal disorders SBP. Due to the limited amount of studies and to provide a more transparent account of the neuropsychological profile of (SBP), we have divided the results as follows: (i) comparison of neuropsychological functioning between BP-I and BP-II and (ii) neuropsychological functioning in SBP.

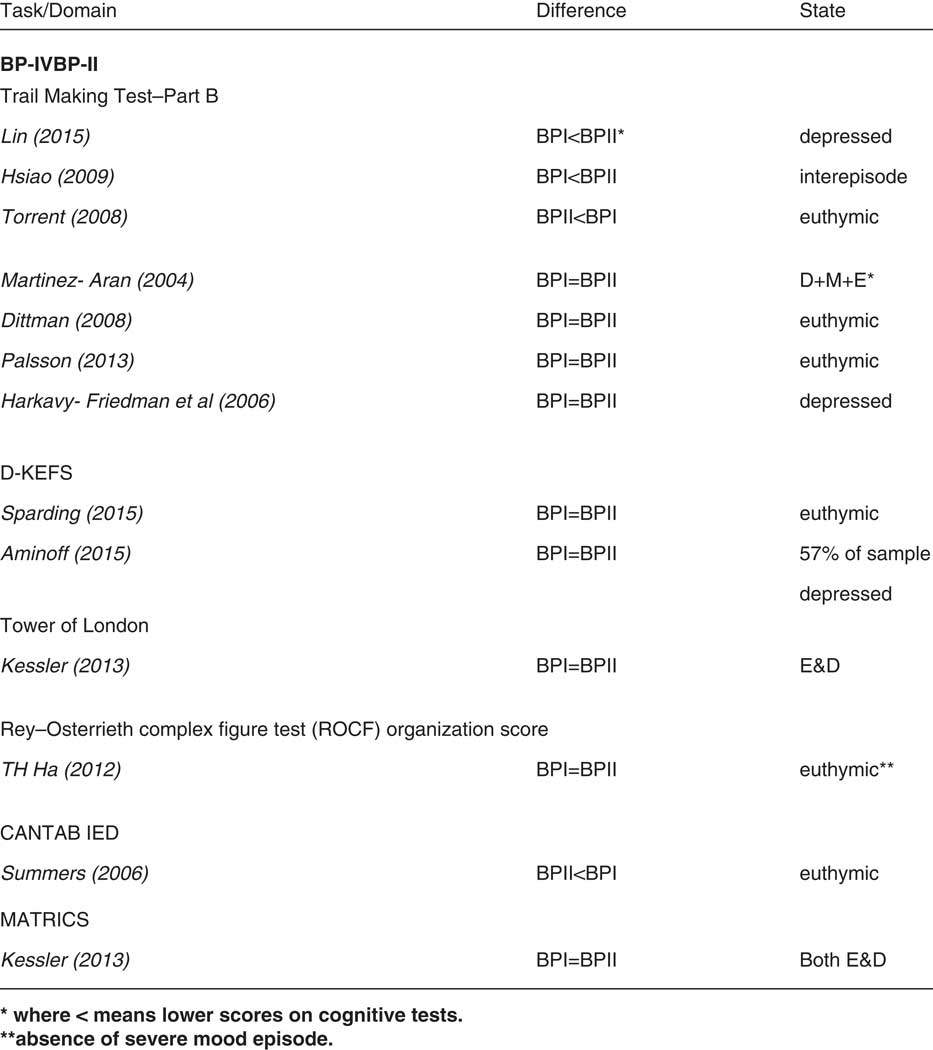

Figure 2 BP-I vs BP-II executive function.

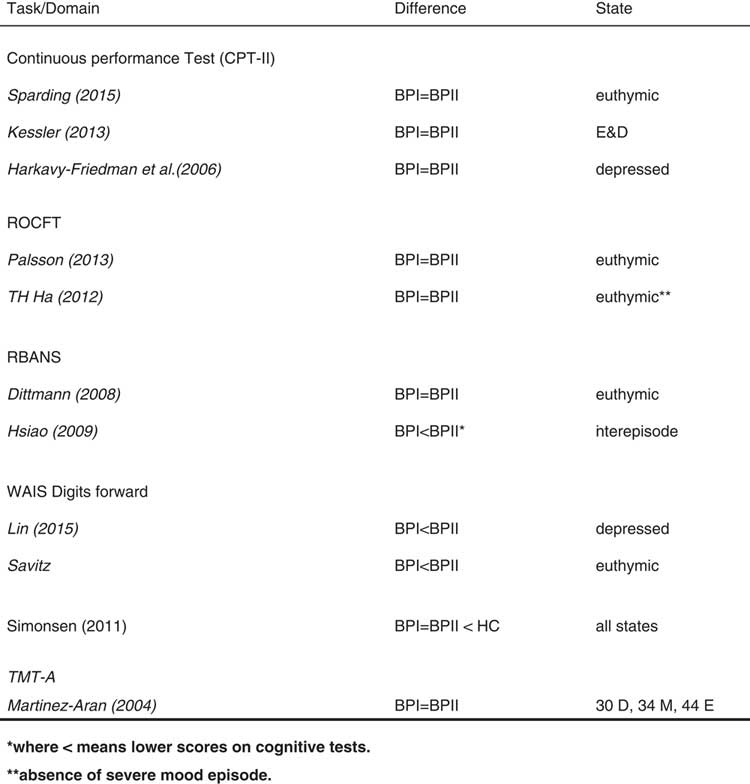

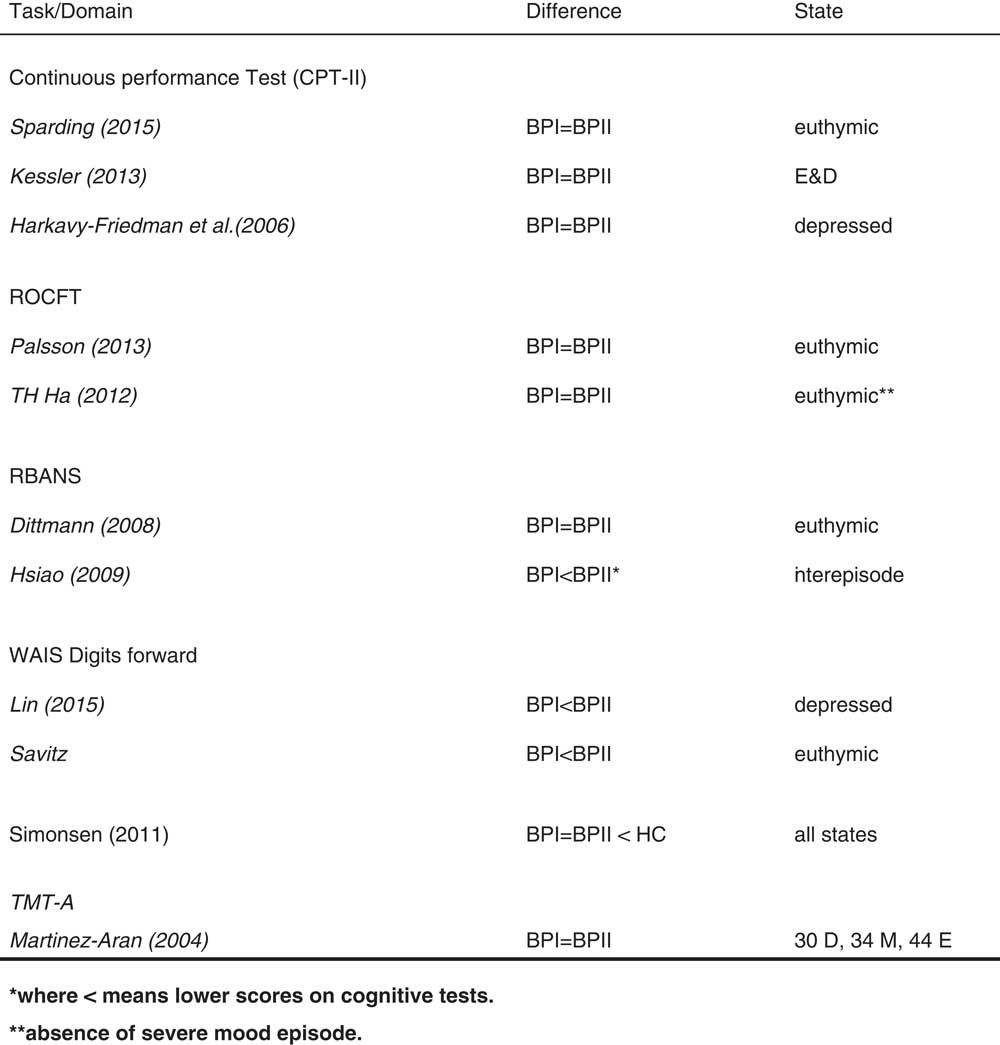

Figure 3 Attention in BP-I v. BP-II.

Figure 4 Verbal memory.

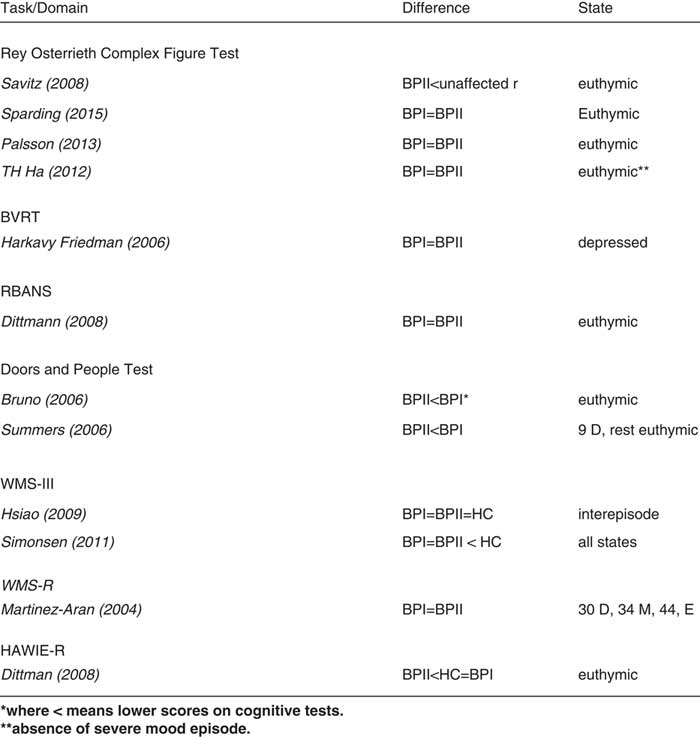

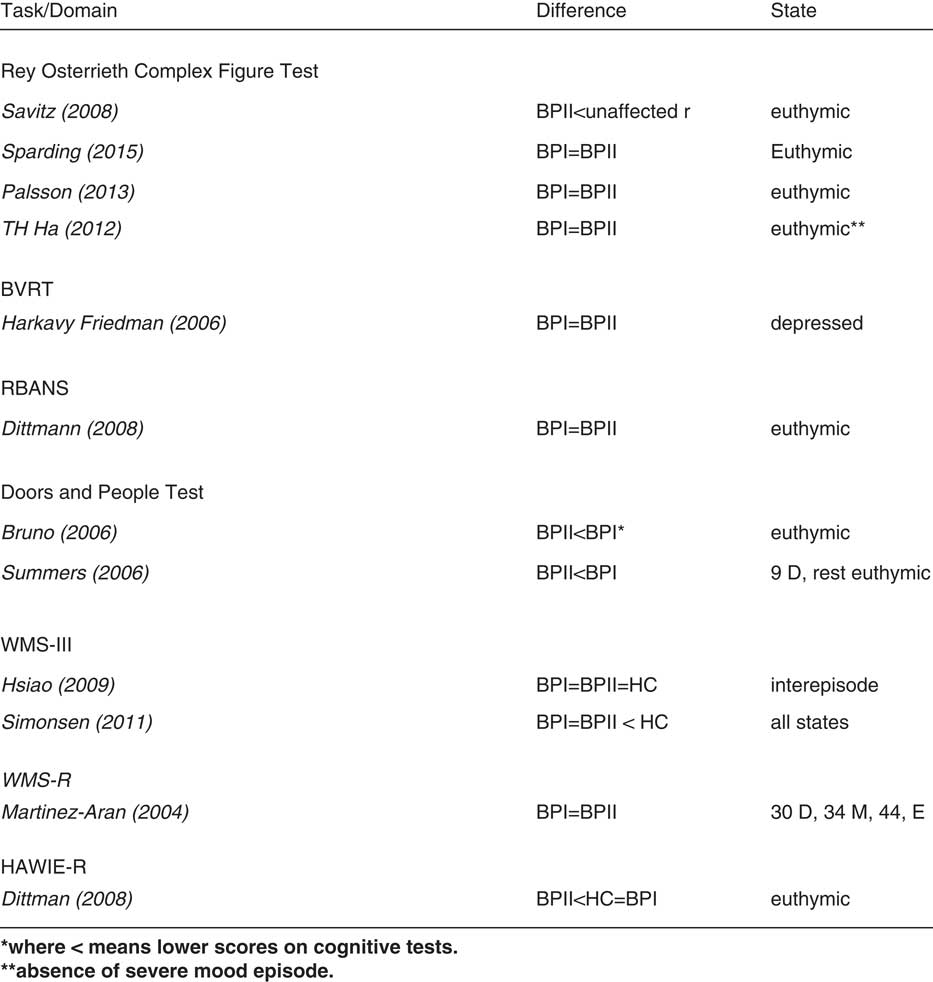

Figure 5 Visual spatial / working memory.

Figure 6 Working memory.

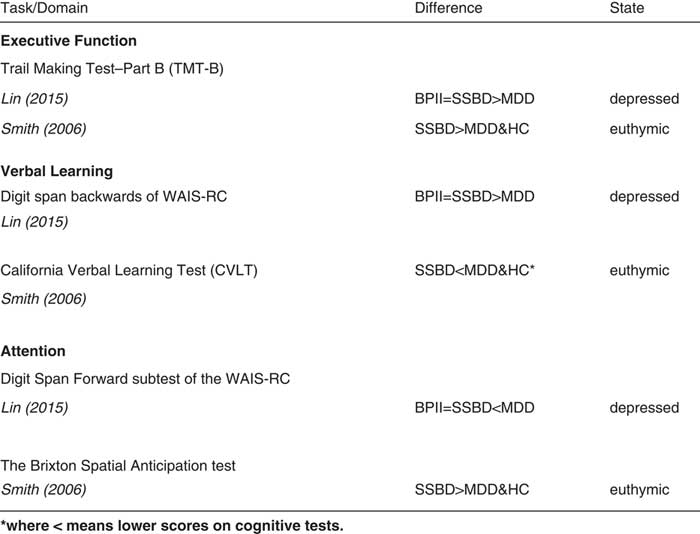

Figure 7 SBP vs MDD vs BP-II.

Global intellectual function

Most of the studies (11 of 17) included an IQ measure in their analysis, all of which failed to detect significant differences in the IQ of BD II patients compared with BD I patients, and between subthreshold disorders and both major depressive disorders and healthy control subjects.

Executive function

Most of the articles (13 of 17) looked at executive function, all of which directly compared EF between BP-I and BP-II. All patient groups scored lower on tests compared to healthy controls (see Figure 2). Nine of these 13 studies showed no difference in cognitive dysfunction between groups, with Sparding et alReference Sparding, Silander and Pålsson 24 concluding that EF most reliably detected cognitive impairments in the patient group using the Trail Making Test B as their cognitive task. Ha et al also found no difference between groups and concluded that executive dysfunctions exert additional influence on memory impairment. Both Sparding et al’s and Ha et al’s samples were euthymic, along with those of 3 other studies, ie, 5 euthymic studies that found no difference in total. There were 4 studies that showed a different profile between BP-I and BP-II, 1 in a depressed sample, 1 euthymic, and the other 2 had a mixed sample of both euthymic and depressed patients.

Attention

Many of the studies (11 of 17) looked at attention, all of which directly compared scores on attention between BP-I and BP-II. Most studies used the Continuous Performance Test (CPT-II) as their cognitive measure to assess attention. See Figure 3.

Two studies, 1 in an inter-episode sample and 1 in an “all states” sample, found BP-I to be more cognitively impaired that BP-II. One other study found BP-I to be more cognitively impaired that BP-II, this time in a euthymic sample. Eight studies found no difference between BP-I and BP-II, 3 of which were in euthymic samples.

Verbal learning and memory

Almost all studies (15 of 17) looked at learning and verbal memory, all of which directly compared neuropsychological performance between BP-I and BP-II (see Figure 4). Six studies in total found that BP-I performed significantly worse than BP-II in measures of verbal memory. Four of these studies were in a euthymic sample, 1 in a depressed sample, and 1 in an “all states” sample.

Seven studies found no difference between BP-I and BP-II in verbal memory, 4 of which were euthymic samples, 2 were both euthymic and depressed samples, and the other 1 was a depressed sample. Two studies found that BP-II had more verbal memory impairment than BP-I; however, the small sample size of BP-II in 1 of these studies should be taken into account, as it could have led to type-II errors.

Visual spatial working memory

Twelve out of 17 studies looked at visual spatial working memory (see Figure 5). Seven studies in total showed no difference, 5 were in euthymic samples, 1 in a depressed sample, and the other in an “all states” sample. Two studies found that BP-II patients were more cognitively impaired than BP-I. Two showed a difference between the 2 patient groups, and 1 found BP-I and BP--II to have no impairment, ie, similar performance to healthy controls.

Working memory

Ten out of 17 studies looked at working memory, all of which directly compared BP-I and BP-II. All studies showed patient groups to be more impaired than healthy controls. Seven studies showed no difference between BPI and BPII, 4 of which were euthymic samples (see Figure 6).

Neuropsychological function in subthreshold bipolar disorders

Two out of the 17 studies included in this review investigated neuropsychological functioning in subthreshold bipolar disorders, comprising the only available literature on this subject, to the authors’ knowledge. Both studies investigated the 3 cognitive domains of executive function, verbal memory, and attention and used a strict unipolar MDD sample for comparison, while only 1 also included a BP-II sample (see Figure 6). One study, in a depressed sample, showed that individuals who met criteria for a bipolar spectrum disorder were more cognitively impaired than those with strict unipolar MDD, while they shared a similar cognitive profile to BP-II. The other study, in a euthymic sample, showed that individuals who met criteria for a subthreshold bipolar disorder performed cognitively better than strict unipolar MDD. This study did not include a BP-II comparison.

Discussion

This review set out to (a) provide an update on neuropsychological functioning in BP-I and BP-II, (b) review all literature pertaining to neuropsychological functioning in SBP, and (c) discuss the plausibility of a dimensional approach to understanding bipolar disorders. Regarding (a), we found that when accounting for the cognitive domains of executive function, verbal memory, attention, working memory, and visual spatial working memory, more studies than not show a similar cognitive profile between BP-I and BP-II. Two additional studies found that BP-II performed worse than BP-I in visual spatial working memory. Regarding executive function, 9 out of 13 studies found no difference between these patient groups, most of which (5 of 9) consisted of euthymic samples with large sample sizes (64 BP-I vs 44 BP-II, 65 BP-I vs 38 BP-II, 67 BP-I vs 43 BP-II, 37 BP-I vs 46 BP-II, 127 BP-I vs 72 BP-II), and the majority of which (4 of 9) used Trail Making Test B (TMT-B) as their measure for executive function. TMT-B has been validated to test an individual’s cognitive flexibility, which some researchers understand as executive function. Clinicians should be aware of the severity of cognitive impairment in BP-II, particularly in the areas of executive function, verbal memory, attention, and visual spatial working memory. Important potential confounding factors for why some studies show BP-I to have a more severe cognitive profile than BP-II will be highlighted below in the limitations section.

Considering (b), SBP patients share a similar cognitive profile to BP-II and have a different cognitive profile to strict unipolar MDD, ie, in the areas of executive function, attention, and verbal memory. Although the sample size was generous in both studies, findings need to be interpreted with caution, mainly due to this conclusion being based on a mere 2 studies but also due to other important reasons which are highlighted below in the limitations section.

Last, we come to (c), and utilizing our findings from both (a) and (b), we can see how neuropsychological alterations may appear similar across subtypes of bipolar disorders, revealing that this condition may be better understood as a spectrum. With this evidence, therefore, we can conclude that neuropsychological functioning, particularly in the areas of executive function, verbal learning, and attention, may represent an endophenotype for 1 current categorical classification, ie, bipolar disorder and related subtypes. These findings are directly applicable to other mental illnesses, and dimensional approaches should be used to better our understanding. We have seen how cognitive dysfunction seems to play an important role across the bipolar spectrum, and scientists are urged to utilize such dimensional approaches when investigating neurobiological underpinnings. How such alterations compare across current DSM-5 classifications of mental illness (eg, major depression, bipolar disorder) would be an interesting undertaking. We have not seen much success with genetics and imaging studies so far; however, research on cognition and neuropsychological testing could pave the way forward. The field is in its infancy, and if we are to move in the right direction, we need to refine our approach to elucidate important clinical factors such as cognitive function and related processes. Investigating the neuroscientific underpinnings of cognition is of equal importance, and below we discuss this topic further.

Limitations

The findings of studies included in this review have many limitations.

BP-I vs BP-II limitations

Medication

An important limitation to be considered with regard to the studies included in this review is the use of antipsychotics not controlled for in these studies. While some studies suggest BP-II is similar to BP-I, many have found different cognitive profiles between the 2 groups, and 1 important reason for this may be due to the differential use of medication within samples. For example, Palsson et al in Sweden found that bipolar type I and type II were cognitively impaired compared to healthy controls, and there were no statistically significant differences between the 2 subtypes (I and II). The strongest predictor of cognitive impairment within the patient group was current antipsychotic treatment. Palsson et al suggested that the type and degree of cognitive dysfunction is similar in bipolar I and II patients; they add that “treatment with antipsychotics—but not a history of psychosis was associated with more severe cognitive impairment” (p. 1).Reference Palsson, Figueras and Johansson 35 Given that patients with bipolar I disorder are more likely to be on antipsychotic drugs, this might explain why some previous studies have found that patients with type I bipolar disorder are more cognitively impaired than those with type II.Reference Palsson, Figueras and Johansson 35 Furthermore, Kessler et al found that a high proportion of patients with therapy-resistant BP-I or BP-II depression exhibited global neurocognitive impairments with clinically significant severity.Reference Kessler, Schoeyen and Andreassen 23 The cognitive impairments were more common in BP-I compared to BP-II patients, particularly processing speed. However, there were other important differences between the samples including the BP-I group having had a shorter duration of education and more BP-I patients taking anti-psychotics. Many patients with this disorder take several psychotropic medications at varying doses, and it is unknown what the cognitive effects of combined therapy might be, particularly over time.

Neuropsychological tests

A further limitation of the studies in this review is that each utilizes a wide variety of different measures, each with its own limitations, and it is clear that a consensus should be made on the tasks that most likely test the most important cognitive domains. This review suggests TMT-B for executive function, CVLT for verbal learning and memory, N-back working memory tool for visual working memory, and the Continuous Performance Test (CP-II) or Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) for attention to be the most suitable.

Comorbidities

Furthermore, an important limitation that needs to be considered is that comorbid conditions have not been discussed to much extent in many of the studies included in this review. Comorbidity (psychiatric and medical) in bipolar disorders is generally very high, and this is clearly of clinical importance, but even more so if we are to begin to attempt to understand the etiology of cognitive impairments. Comorbidity is especially high in BP-II and SSBD, particularly in terms of anxiety disorders and personality disorders, and it has been questioned whether multiple individual diagnoses (constructs largely derived from clinical presentation as categorized in the DSM-5) are the most efficient way of moving forward in our attempt to understand frequently co-occurring symptoms. Severity, for example, is not considered in this way.

SBP limitations

Patient selection

One important limitation is the criteria used in each study’s samples. For example, both authors of the 2 SBP studies in this review use the term spectrum disorders SBPReference Lin, Xu and Lu 25 and BSDReference Smith, Muir and Blackwood 36 with inclusion criteria based on the definition by Ghaemi et al and Akiskal and PintoReference Akiskal and Pinto 38 , respectively. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain from both authors’ definitions and the details presented whether these patients would meet criteria for BP-NOS or SBP-ME (mixed episodes), and indeed they could also be cyclothymic. For example, Lin et al categorically re-assigned those with MDD into 81 SBP (36 bipolar II 1/2, 9 bipolar III, and 36 bipolar IV using the Akiskal and Pinto criteria; please see Appendix 2 for reference to this criteria). Smith et al used definitions according to BSD diagnostic criteria from Ghaemi et al (see Appendices). Despite the availability of more defined categories, such as in the DSM-5, there is a paucity of studies that use such criteria, and future studies would benefit from such a refined approach.

Mood state

A further limitation is that although SBP patients were shown to be different from strict unipolar MDD, the results of the 2 available studies to date are contradictory, which may be due to the different SBP criteria used or it may be due to the different mood states recruited within groups. For example, Smith et al found euthymic patients with BSD were significantly better than MDD patients and controls on tests of executive function and verbal memory, whereas Lin et al found the opposite in a sample of depressed patients. On the other hand, Lin et al’s data suggest that patients with BSD perform significantly worse than strict unipolar MDD. Further research might benefit from using the strict DSM-5 criteria along with a strict euthymic sample.

Conclusions

It appears pertinent that bipolar disorder type II (BP-II) has cognitive impairments that are just as severe as they are in bipolar disorder type I (BP-I), and in some cases more so, specifically in the areas of executive function and visual spatial working memory. Executive function is a construct that is most vulnerable to the effects of stress exposure, and this might be even more pronounced with both of these conditions. Reasons for this are unknown. However, it is interesting that Smith found in his sample that patients with subthreshold disorders performed significantly better than both MDD and healthy controls. What happens to individuals with subthreshold bipolar disorders over time?

The possibility of a link between bipolar disorder and positive attributes such as intelligence and creativity have been discussed since antiquity.Reference Smith, Anderson, Zammit, Meyer, Pell and Mackay 39 Whether, and how, IQ may relate to neuropsychological dysfunction is unclear; however, Smith et alReference Smith, Anderson, Zammit, Meyer, Pell and Mackay 39 found that childhood IQ was associated with bipolar disorder, and that intellectual function may be an endophenotype biomarker for bipolar disorders. If SBP were found to be an early onset BP-II or BP-I disorder, it might be likely that intelligence is indeed, as Smith and colleagues suggest, a predictor and endophenotype biomarker for bipolar disorders,Reference Smith, Anderson, Zammit, Meyer, Pell and Mackay 39 and that such factors may lead to more severe alterations in mood, activity, and biological rhythms.

Implications

Unrecognized bipolarity is thought to be a significant factor contributing to treatment resistance in depression,Reference Correa, Akiskal, Gilmer, Nierenberg, Trivedi and Zisook 40 and is therefore of great potential significance as a possible predictor of treatment response. A traditional categorical approach to major depressive disorders in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) and subthreshold bipolar disorders (SBP), in particular BP-NOS, may be limiting for research purposes, and a dimensional approach to neuropsychiatric illnesses such as the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) could be considered as a model to work toward. RDoC is an attempt to create a new kind of taxonomy for mental disorders by bringing the power of modern research approaches in genetics, neuroscience, and behavioral science to the problem of mental illness.Reference Cuthbert and Insel 41 A stratified model such as RDoC may lead to better understanding of these underlying conditions so that more appropriate treatments can be implemented for patients.

Neuropsychological functioning represents one of the key RDoC constructs that crosses DSM-5 boundaries and may substantially enhance our understanding of the pathophysiology of diverse illnesses, such as the heterogeneity of MDD. While RDoC is still in its infancy, nevertheless, future research should work toward an RDoC approach. A pragmatic precision medicine model currently being explored is “the development of a neural circuit taxonomy suited to clinical actions to address the gap between brain imaging advances and practice” (p. 2).Reference Williams 42 William’s approach provides the foundation for a “taxonomy of putative types of dysfunction, which cuts across traditional diagnostic boundaries for depression and anxiety and includes instead distinct types of neural circuit dysfunction that together reflect the heterogeneity of depression and anxiety.”Reference Williams 42 This taxonomy provides a foundation for building research evidence to help guide clinical practice. Cognitive remediation strategies are one such example. Future research should investigate cognitive functions and neural circuits across major depressive disorders by administering short neuropsychological assessments and carry out MRI studies to gain a further understanding of the underlying mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction.

Protocol for future studies

Regarding neuropsychological tests that should be used, this review suggests TMT-B for executive function, CVLT for verbal learning and memory, N-back working memory tool for visual working memory, and Continuous Performance Task for attention. The THINC batteryReference McIntyre, Best and Bowie 43 is a digitized cognitive test application designed to assess cognitive function in MDD and administers the following cognitive test components: Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), Trail Making Test B (TMT-B), Choice Reaction Time (CRT) One-back working memory tool, and Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-5 Depression (PDQ-5-D). This tool can be administered in 20 minutes, and although it does not involve a verbal learning task, it may be a short and concise method of assessing and distinguishing bipolar disorders from MDD. Strict euthymic criteria should be used in all patient groups, to rule out the effect of sub-syndromal depressive symptoms. Including euthymic samples has also been recommended by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Targeting Cognition Task Force.Reference Miskowiak, Burdick and Martinez-Aran 44 Other key methodological challenges they suggest are lack of consensus on how to screen for entry into cognitive treatment trials, define cognitive impairment, track efficacy, assess functional implications, and manage mood symptoms and concomitant medication. The authors’ recommendations are to “(a) enrich trials with objectively measured cognitively impaired patients; (b) generally select a broad cognitive composite score as the primary outcome and a functional measure as a key secondary outcome; and (c) include remitted or partly remitted patients” (p. 1).Reference Miskowiak, Burdick and Martinez-Aran 44 Furthermore, there are no studies in this review that have used the most recent DSM-5 criteria for SBP (ie, BP-NOS), and future studies should address this.

Strengths and weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first review to investigate systematically the literature on the relationship between neuropsychological dysfunction and subthreshold bipolar disorders. One main strength of this review is the culmination of a quality assessment of each study included, the results of which indicate that there are a significant number of potential confounders not controlled for, such as use of antipsychotics particularly in BP-I, history of psychosis, and comorbidities. The review discussed the implications of these confounders in more detail, suggests that a consensus should be agreed upon as to how studies should be carried out, and includes a recommended protocol for future studies. A meta-analysis was not possible with the available data from current studies, something which would be of real value in the future if methodology of studies will allow. The conclusions drawn from the SBP studies are based on 2 articles, and more research in the area is necessary, particularly studies that utilize a more refined methodology approach, as outlined above. Last, we only used English language articles. (Tables 4–9)

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852918001463