The United States has played an ambivalent role in the multilateral governance of finance since the end of World War I. An international committee headed by American Owen Young initiated plans for a Bank for International Settlements (BIS); however, the Hoover Administration distanced the U.S. government from the institution before it commenced operations. Disproportionate American power would seem to produce treaty results attractive to domestic American constituencies. Banking groups have increasingly participated in global processes over time, both with regard to their numbers and the intensity of their efforts. Yet these same groups frequently reject attempts at global coordination through formal international organizations of the type that occurs in other areas of U.S. foreign policy.Footnote 1 Such behavior baffles American allies and poses an obstacle to efforts at multilateralism on the part of the world community. What explains the paradoxical pattern of American participation in multilateral efforts to coordinate financial governance?

I propose a model of the American foreign policy process in finance that builds upon a foundation of the standard interplay among the governmental elements in the field of U.S. foreign policymaking: presidential administrations, executive branch agencies, congressional committees, interest groups, and the media. Yet I argue that—unlike other foreign policy areas—the domestic and international processes cannot be distinguished from each other in creating the political conditions necessary to foster multilateralism in this area. Decisions made in a global crisis lead to the formation of new domestic institutions and groups. The expansion leads to a higher number of both institutional and partisan veto players, or individuals, interest groups, and agencies that must be satisfied in the next round at both the domestic and international levels.Footnote 2 To put it another way: In finance, the United States cannot cooperate externally without internal cooperation among foreign policy–making actors who push and pull each other constantly. While these governmental players cannot always prevent the United States from cooperating (or truly veto a change in policy), they can alter the way that the United States cooperates, particularly with respect to the involvement of Congress and federal government agencies the interest groups lobbies. The process is propelled by the competition among banks for market share at both the domestic and international levels that has no clear beginning or endpoint.

The complexity of American foreign economic policymaking in finance matters to the world because the international monetary and financial regimes are joined now in such a way that the solution to every problem affects the distribution of wealth both among and within national economies. American banks and capital markets represent a large percentage of the global whole, and thus exert disproportionate importance. As others have argued, the structural power of the United States figures prominently in attempts to explain why so little cooperation appears to have been achieved since the financial crisis of 2008.Footnote 3 Yet such explanations do not delve into the internal processes that result in support, or lack of support, for the multilateral form. Similarly, distinctive domestic and international processes that are equally as important for their magnitude operate in the states that comprise the European Union; however, the governmental institutions of monetary union and banking regulation in the European Union have been investigated elsewhere.Footnote 4

To demonstrate the model, I revisit the archival record and major historical treatments of American participation in the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) specifically. I supplement this evidence with background interviews with policymakers involved in the policy process. The history of this participation explains variation through the governmental mechanisms the United States has used in its history, and the degree of internal coordination that can be achieved among regulators, congressional committees, the presidential administration, and major interest groups in the affected banking segments, rather than a stark dichotomy between cooperation and non-cooperation. The article proceeds in five sections. The first presents a heuristic model for understanding how cooperation can be achieved in the international American policy cycle concerning financial governance. The next two sections demonstrate the model of American participation in the two cases of the BIS and BCBS (which is headquartered at the BIS) at their inceptions. The fourth section explores how this model can be used to understand later cycles with respect to the key elements of American foreign policymaking in this area that produce ambivalence. The final section offers conclusions about future research.

The U.S. foreign policy process in the governance of finance

Pioneering models of foreign economic policymaking explained state behavior through different domestic political systems, constituencies, and the material interests within them.Footnote 5 In recent years, work on the coordination of financial governance veers from the earlier approaches and focuses on general investigations at the systemic level. To different degrees, these authors explore the relationship between global governance mechanisms and the capacity of national banking regulators to supervise national banks, yet ignore how international initiatives are filtered through the domestic policy processes of governments, each with its distinct state and societal characteristics—or the European Union with its mixture of state and international organization structure.Footnote 6 Without such a domestic component, this literature implicitly assumes a high degree of similarity in how governments operate with respect to diplomacy, lobbyists, and policymaking procedures. While this work has added depth and precision towards understanding how decentralized rules without a coercive authority to enforce them are constructed at the international level, it leaves the specifics of states and their societies out of the picture.

American foreign policymaking

What makes American foreign policymaking distinct from other industrial democracies in determining a course of action? Two features stand out: the participation of Congress and the involvement of competing regulatory agencies in determining a course of action.Footnote 7 Given the notion of separation of powers in the U.S. government, the Constitution gives Congress the power to coin money as well as some other powers related to foreign policy making such as the power to raise an army and declare war; yet it gives the President the power to negotiate treaties and to act as Commander in Chief of the armed forces. Although both Congress and the President have played a role throughout American history, Congress does not always assert itself.

To understand when and why Congress does assert itself requires political as well as legal insight. Lindsay hypothesizes that when Americans believe the country faces an external threat, they also believe that it needs strong presidential leadership.Footnote 8 When Americans believe that international engagement could itself produce a threat, or there are otherwise few threats, they support congressional activism. Engagement can take many forms. Congress can fund, or refuse to fund, a particular policy. It can hold hearings on sensitive matters in order to attract media attention. Members of Congress can pressure agency heads through private channels.Footnote 9 It can write laws that direct the activities of agencies in multilateral forums; however, given the “soft law” features of many financial agreements, legislation is rarely needed.Footnote 10 It is easiest for policy makers to avoid Congress when at all possible to prevent intervention. Yet opponents of a given policy are likely to seek assistance there.

The second distinctive feature of American government in foreign policy making is the politics at work among federal agencies and within them. Allison introduces the notion of bureaucratic competition into understandings of foreign policymaking, wherein agencies compete for mandates, budgets, and personnel.Footnote 11 Hence, they have their own interests in how a particular policy is conducted as well as its outcome.Footnote 12 While Allison's model has been criticized, work after the Cold War has argued that as the United States becomes enmeshed in a host of issues above and beyond the military, myriad U.S. agencies—mostly oriented toward domestic affairs—have jurisdiction over, and are involved in, making policy. As domestic agencies, they frequently lack the language skills, international affairs experience, or foreign policy background to carry out their assigned roles successfully.Footnote 13

Such widespread agency jurisdictions are particularly complex in finance due to the ambiguous division of responsibilities between the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department, and within the Federal Reserve System's Board of Governors in Washington (FRBG) and Regional Reserve Bank of New York. The Federal Reserve System is not precisely a central bank as other countries’ are, albeit it performs central banking functions of monetary control as well as supervisory regulation of those private commercial banks and bank holding companies entrusted by Congress to it.Footnote 14 Since the Federal Reserve Act was passed in 1913, intervening laws re-arranged areas of international responsibility, particularly with respect to regulation of banks and capital adequacy. The Act initially gave the Federal Reserve the power to set monetary policy, but each of twelve Regional Reserve Bank directed open-market operations in its own district. The Banking Act of 1935 centralized authority in the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and reduced the independence and stature of the Regional Reserve banks.Footnote 15 Among them, however, the FRBNY retains a special role, including acting as the primary contact with other foreign central banks.Footnote 16 Nonetheless, the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 established the Exchange Stabilization Fund of the U.S. Treasury in order to contribute to exchange rate stability and counter disorderly conditions in the foreign exchange market. The Act authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to use the fund under his or her exclusive control, subject to the approval of the president. The FRBNY conducts the related transactions. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and to a lesser extent the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Corporation (CFTC) have each expanded their activities into the international arena.

Therefore, in order to account for the “domestic politics” aspect at the intersection of international relations and comparative politics, theory must account for congressional involvement (or lack thereof) and the competition among myriad agencies involved. Which actor is at work across the domestic/international divide: the president? An executive branch department? A congressional committee? An independent regulatory agency? A political party? Interest groups attached to large banks or small ones? How has this actor's past actions shaped the decisions that will occur in the future? What exogenous shocks have altered the playing field? The answers to these questions are not consistent across time in the United States because the actors themselves have changed, as have their own internal cleavages.Footnote 17

The cycle of foreign policy

Attempts to depict the foreign policy process begin with the premise that any country's foreign policy decisions result from both internal and external sources. Many authors offer a diagram of a funnel, with a feedback arrow at the bottom of the funnel running back into the wide set of inputs at the top.Footnote 18 Since decisions occur across time, the foreign policy output becomes its own input at the next stage in a dynamic process where no factor explains a decision exclusively, and where any decision cannot be separated from those that preceded it.

Unlike other policy areas, the funnel does not offer an accurate depiction of the process in finance. The American public does not have the same intuitive understanding of the nature or degree that a financial threat poses to their well-being as they do in more traditional areas of national security, such as a nuclear or terrorist threat. Moreover, most transactional banking information is highly confidential by necessity. Hence, the earliest signs of a financial crisis are only apparent to regulators and banking institutions themselves, limiting the width of the internal and external participants that feed the process to a group of fragmented regulators that, in turn, inhibits a consistent policy outcome. Rather than narrowing, these groups broaden as the process moves forward through successive rounds.

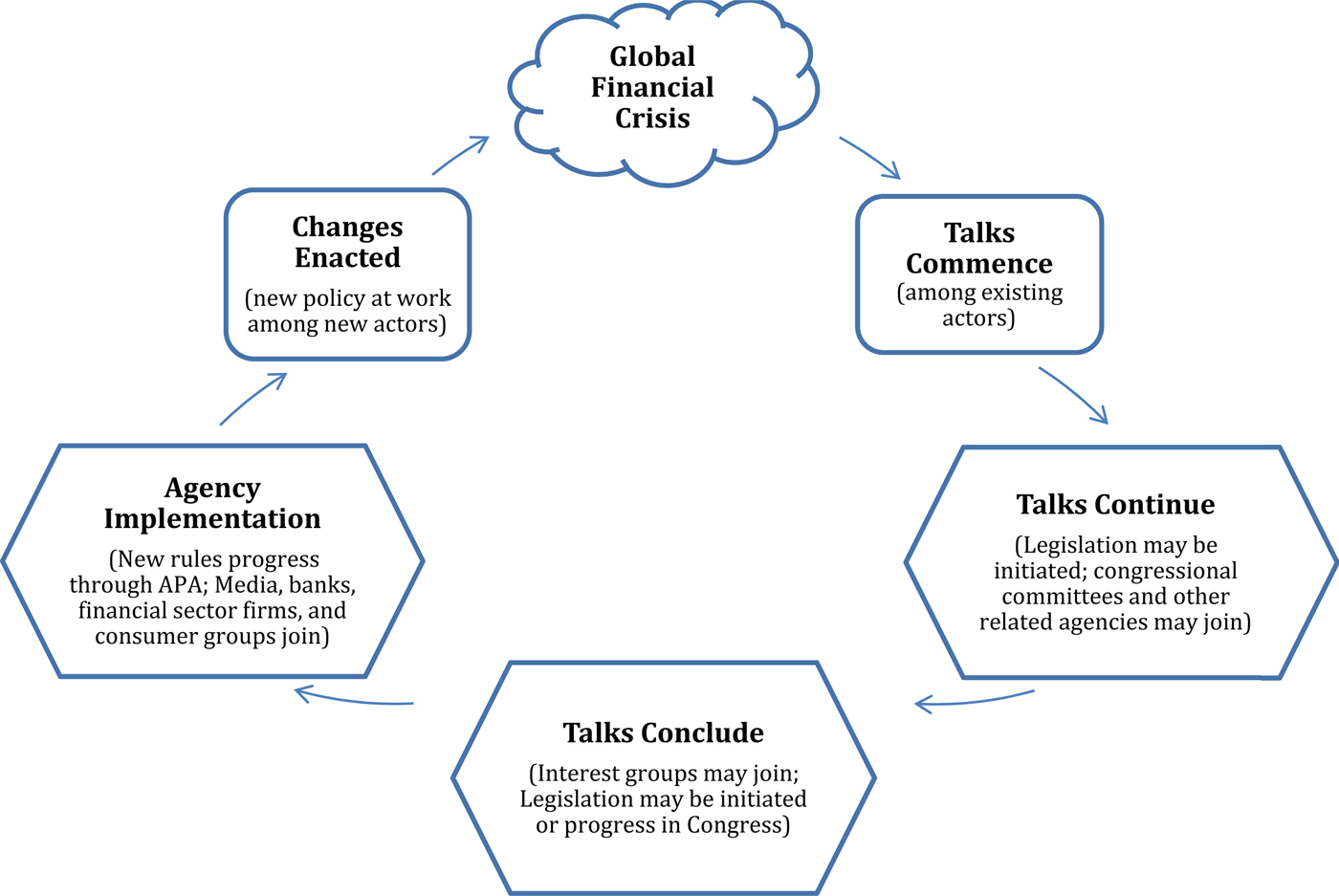

Rather than using a funnel that leads to a clear policy, figure 1 depicts the successive phases of American participation in efforts to cooperate in financial governance following a global financial crisis. I represent the process as an ongoing cycle, wherein the number of participants widens, rather than narrows, as it progresses. Since the end of fixed parity in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1971, each cycle following a crisis has resulted in a larger number of agencies that participate at the outset with more actors that might prefer to use Congress as a forum to pursue their goals and frequently seek diverging methods of implementation of an agreement. Likewise, more arenas in which to achieve results raises the number that must be satisfied in order to cement any substantive change.

Figure 1: The Cycle of U.S. Foreign Policy in Financial Governance

The first two stages of the cycle occur at the international level. At the first stage, a financial crisis rises to the level where central banks, treasuries, and financial actors perceive a need for multilateral cooperation. The need for secrecy is paramount because the threat of an imminent bank collapse can quickly turn the threat into reality. The Federal Reserve and other regulators can take immediate action within the United States and to a lesser extent internationally. At the second stage, talks commence. Within the U.S. government, the FRBNY had been the initial agency representing U.S. interests in an informal manner. Later, the FRBG, OCC, FDIC, Treasury, and SEC have taken more active roles. After 1971, each agency and the Presidential administration became involved at an earlier stage. Moreover, different agencies seek to negotiate in different forums where they perceive to hold an advantage. Prior to 1971, the major outlets were the BIS, IMF, and G10 deputies with a far more restricted number of American agencies. After 1971, the BCBS and other combinations of central banks from industrial states began to appear on an ad hoc basis. As the financial crises of the 1980s and 1990s progressed, the Basel Committee became a more permanent entity and the IMF re-emerged as a venue to resolve sovereign debt. Eventually, the G20 and Financial Stability Forum (FSF—now the Financial Stability Board—FSB) formed.

In the next three stages of the cycle, domestic American governance structures play a greater role: chiefly, congressional committees, domestic agencies, and interest groups. At the third stage of the process where talks continue, congressional committees may seize on a particular issue or hold hearings where interest groups can air their positions on the U.S. position. Congress may also initiate legislation to provide funds, or deny them, to a particular effort. Hence, participation widens additionally, making the outcome more difficult. By the fourth stage, talks conclude and an agreement is reached. Remaining interest groups formulate a strategy with respect to the agreement and Congress may play a role if further legislation is needed.

In the fifth stage, federal agencies must implement the agreement, which widens the number of participants even further. When Congress writes the goal of a particular policy into a statute, but does not detail how to achieve it, agencies must write rules to prescribe the specifics of government policy.Footnote 19 Agencies may also write rules to change government policy based on the terms of an informal agreement if the agency already has existing authority in that area. According to the rulemaking process set forth in the Administrative Procedure Act, agencies and interest groups must have the opportunity to participate.Footnote 20 They generally do so by submitting comment letters to a proposed rule and meeting with officials at the agency in question. The results can help the agency gauge what enforcement might be necessary, or whether or not a lawsuit might challenge the rule before it is implemented.Footnote 21 The affected communities are usually within the United States; however, in the financial services area, they could be in other countries too. Since participants in the rulemaking process must know that a rule is under development and how it might affect their interests, groups, organizations, firms, and other governments (U.S. state and local) are the most common participants, albeit individuals have increased their participation since the advent of electronic submissions.

In the last stage of the cycle, the agencies must enact the rules, making the new policy a reality. Some agencies may enforce the new rules more vigorously than others. Banks and financial firms subject to the new rules may sue the agency on grounds that it lacks the statutory authority in the area (if legislation was not involved). New legislation may be needed to clarify and issue or clarify the jurisdictional issues. In successive iterations of the process, actors that joined at later stages in previous cycles become involved in earlier stages as they learn from those experiences what their stakes are in the outcome of these particular negotiations.

American bureaucratic politics leading to a banking and financial regime

In the financial domain, issues operate within an international economic regime that both the American state constructs, and is constructed by. Since the twentieth century, the regime has both a monetary and a financial component. One facilitates international transactions with the exchange of monies to pay for them; the other provides the investment capital that is required for trade or manufacturing and development to take place around the world.Footnote 22 Flows of international capital and foreign investment are conducted in money, so that changes to the two components are difficult to separate.Footnote 23 Nonetheless, different formal international organizations handle different issues connected to money and finance. The monetary system and exchange rates are more closely associated with the IMF; and the financial system and the integration of capital markets are more closely associated with the BIS and later BCBS. While both aspects are important, I focus on the growing governance of finance for purposes of the historical examination that follows because it has received far less attention in the academic literature on the topic than the more formal mechanisms associated with the IMF.

Informed by archival evidence, the review that follows of the history of the shocks in the 1970s illustrates the policy process with regard to the expansion of actors involved in the BCBS's four major agreements, the Concordat, Basel I, II, and III. As the system of fixed exchange rates unraveled in the early 1970s, there was effectively no international financial system in place because almost every country maintained capital controls. Although a market for deposits denominated in foreign currencies emerged in the 1950s and grew in the 1960s, the market's growth escalated in the 1970s. West European and other international banks took greater quantities of such eurocurrency deposits, particularly in dollars, in order to escape the limits on interest charges by Regulation Q in the United States. The Soviet Union participated in the market in order to secure its hard currency deposits in European banks. Therefore, eurocurrency markets developed as offshore centers where dollars could be traded outside the regulatory environment of the United States. Their growth eventually undermined the United States’ authority to guarantee the value of the dollar in the fixed rate system.Footnote 24 Petrodollars that flooded the market after the oil price rise in 1971 compounded the problem. The result of these developments was that the financial and monetary components began to influence each other.Footnote 25

Bank Herstatt, Franklin National, and domestic regulation in the New World of global finance

Strains on the fixed exchange rate system were accompanied by domestic problems in the American economy. Throughout the summer of 1971, unemployment was between 6.3 percent and 6.6 percent as real output rose. Prices rose faster than wages. Federal Reserve Chair Arthur Burns began to call for a price-wage policy, although it was not a goal of the Nixon Administration.Footnote 26 In June of that year, Congressman Henry Reuss, Chair of the Subcommittee on International Exchange and Payments of the Joint Economic Committee held a hearing on “The Balance of Payments Mess.”Footnote 27 Reuss and Senator Javits recommended an international conference or severing the dollar's link to gold. The dollar could float temporarily until an appropriate realignment of exchange occurred.

The presidential administration, represented by Paul Volcker, argued that a difference existed between the basic and underlying deficit and short-term capital flows resulting from differences in exchange rates. Volcker's argument was that overcoming inflation at home was the paramount goal, without destroying the system of integrated capital markets, mostly free convertibility of capital, freedom of trade and payments, and reasonably stable exchange rates.Footnote 28 The outflow of dollars continued to rise, and Paul Volcker argued that the crisis had reached its climax. By the weekend of August 15, the Nixon Administration's top economic officials went to Camp David where Treasury Secretary Connally argued that economic policy—both domestic and international—needed to be changed.Footnote 29 The United States devalued the dollar in 1971 and then again in 1973.

The new world of floating exchange rates created a new environment for banks operating internationally and put new pressures on the existing weaknesses of national supervisory and regulatory methods. In the United States, the diffusion of supervisory and regulatory responsibilities among federal and state authorities complicated any efforts at public control of international banking. At the time, most multinational banks were nationally chartered and supervised by the OCC—part of the Treasury. Foreign branches of these banks were authorized by the Federal Reserve but supervised by the OCC. The Federal Reserve authorized the formation and supervision of Edge Act corporations (subsidiaries of national banks organized for the purpose of international activities.) The Federal Reserve also authorized the formation or acquisition of foreign subsidiaries by bank holding companies or member banks. The OCC supervised foreign subsidiaries of national banks, and the Federal Reserve and state authorities supervised foreign subsidiaries of state member banks jointly. The complexity of the situation required cooperation, but created opportunities for differences, given the varying standards for evaluating a bank's condition and the standards required for it to engage in international finance.Footnote 30

Once fixed parity collapsed, exchange trading became a higher risk activity with higher rewards. Two bank failures associated with the new environment prompted calls for action at the international level. The German Bank Bankhaus Herstatt initially encountered troubles from its large foreign exchange business. In September 1973, it suffered losses four times its capital when the dollar appreciated unexpectedly. After the bank changed its strategy to speculate on the appreciation of the dollar (until mid-January 1974), it suffered further losses when the direction of the dollar changed again.Footnote 31 In the other crisis of 1974, the twentieth largest bank in the United States, Franklin National, became heavily involved in foreign exchange in order to compensate for losses in other divisions. Hence, while Franklin National's problems began in domestic markets, its foreign exchange traders sought to make up for losses by speculating heavily in volatile markets without much experience in the area and without much control of their activities by management.Footnote 32

In domestic politics, Franklin National was significant for its size and for its effect on the three regulatory agencies forced to cooperate on behalf of systemic stability: the OCC as the main supervisor, the FDIC as its insurer and the entity that would potentially receive its assets and liabilities in collapse, and the two arms of the Federal Reserve (occasionally playing diverging roles) as the lender of last resort.Footnote 33 The eventual failure took up a considerable amount of the FDIC's personnel resources, because there were negotiations over a five-month period among the FDIC, the OCC, the Federal Reserve, and the bidding banks. Foreign bank branches and foreign exchange speculation complicated the transaction. At the time, a non-New York State American bank could not purchase Franklin and New York State purchasers were limited by antitrust concerns. Hence, foreign banks were more likely merger partners or potential purchasers.Footnote 34

As the time frame lengthened, deposits left the bank that were funded by advances from the FRBNY. Therefore, by the time it closed, Franklin had borrowed $1.7 billion from the Federal Reserve. The FDIC agreed to pay the amount due the Federal Reserve in three years, with periodic payments to be made from liquidation collections.Footnote 35 In September of 1974, it became increasingly difficult to find foreign exchange dealers who would enter into foreign exchange contracts with Franklin National that might help the bank to wind down its exposure. There was also a risk that parties to contracts favorable to Franklin might find reasons not to honor the contracts.Footnote 36 The FRBNY was particularly concerned with this situation because Franklin's unexecuted foreign exchange contracts posed a threat to stability in the foreign exchange markets. The contracts posed a conflict of interest to the FDIC and they were later purchased by the FRBNY.

Here too, foreign central banks cooperated. As with the commercial parties to the contracts, the risk in the Federal Reserve's purchase was that parties to the contracts would renege on the unfavorable ones, arguing that they had contracted with Franklin and not the Federal Reserve. These actions would have destabilized markets already shaken by the Franklin and Herstatt. The other central banks pressed their commercial banks to agree to the transfer of the contracts to the FRBNY.Footnote 37 On 8 October 1974, the OCC declared Franklin National to be insolvent and appointed the FDIC as the bank's receiver. The FDIC also accepted the bid of European-American Bank & Trust Company as the purchaser. “European-American” was an FDIC-insured state nonmember bank owned jointly by six large European banks.Footnote 38

The formation of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

As the international crises of 1974 wore on, the BIS became a locus of activity for managing its impact on the international system. When Franklin's foreign exchange problems grew, the FRBNY informed other central banks. Richard Debs of the FRBNY informed all of the major central banks the week of 11 May 1974. He wanted them to be able to react quickly to any emerging crisis and to understand why the Federal Reserve might have to intervene to support the dollar in exchange markets. The Federal Reserve kept other central banks informed throughout the five months of the crisis. Foreign central banks also cooperated with the Federal Reserve in searching for a bank to purchase Franklin. The regular monthly meeting at the BIS in July 1974 was less than two weeks after Herstatt collapsed and in the midst of the Franklin crisis. The central bankers made vague commitments to cooperate without wanting to specify the conditions for assistance, depending on their national circumstances. Among them, the Bank of England sought international rules that would restrict its responsibilities as a lender of last resort. The British sought to persuade others to adopt this position.Footnote 39

This cooperation among central bankers in the new environment led them to believe that some coordination of supervisory practices and international regulation would be necessary. Once again, the British took the lead through existing arrangements. The G10 had already assigned topics to different “committees of experts” on topics of interest such as the Eurocurrency markets. Although the Federal Reserve was not a member of the BIS, the secretariat invited the FRBNY and Board representatives to these meetings.Footnote 40 Governor Richardson of the Bank of England proposed that the G10 governors establish a Standing Committee on regulatory and supervisory practices that would improve regulation and create an international early warning system.Footnote 41 When the initial Committee on Banking Supervision formed, representatives of the two arms of the Federal Reserve were likewise invited.Footnote 42 Among other questions, the Committee looked into the principle of consolidated bank statements. The Federal Reserve System at the time also sought to improve the regulation and supervision of international banking by establishing a Steering Committee on International Banking Regulation with Governor George Mitchell as Chair. Governor Mitchell independently invited the G10 supervisors to a meeting in 1975.Footnote 43

The Standing Committee was established in autumn of 1974 with its own secretariat at the BIS. Nonetheless, its role was intended to be consultative. At the first meeting, the Committee Chair remarked that it “was not intended that the Committee should engage in far-fetched attempts to harmonize countries’ supervisory techniques. The idea rather was that the members should learn from each other's experience in this field, though they should also consider whether there were any particular techniques that could be recommended to the Governors for general adoption.”Footnote 44 The U.S. representative remarked that after what happened in 1974, the United States had tightened its bank supervision. Nonetheless, no supervisory measures had been taken. There had been some exploratory work on the international side of the banks’ business, concerning ways of evaluating the political and economic risks involved in foreign lending.Footnote 45 At the second meeting of the Basel Committee, the members expressed frustration that a leak had occurred in the press about the first meeting. The Committee chair informed the members that the leak had been from someone with access to reports made after the meeting, and they had been advised to be more discreet in the future.Footnote 46

In 1975, the Committee completed its first major accomplishment in setting forth an agreement on the responsibilities between supervisors in home and host countries—The Concordat of 1975—that attempted to establish an international division of responsibility, common principles, mechanisms for information sharing, and a decentralized mechanism to force supervisors to comply with common standards.Footnote 47 It was modified in 1983, 1990, and 1992.Footnote 48 Nonetheless, there were flaws to the initial 1975 Concordat. First of all, bank supervision in a particular jurisdiction was of limited value because the Concordat did not attempt to establish standards for the quality of that supervision. Secondly, the Concordat was not released publicly for five years, and it was not precise enough to eliminate confusion among supervisors and banks regarding where responsibility rested among supervisors. Lastly, there was not an enforcement mechanism to guarantee that supervisory authorities would comply with its provisions.Footnote 49

American participation as the financial regime matures: Congress and the agencies

In order to demonstrate the proposed model of U.S. foreign policy decision making in finance depicted in figure 1, it is necessary to explore the two aspects of this decision making that account for such ambivalent American cooperative patterns: congressional assertion and agency competition. Since the initial discussions that produced the Basel Concordat were conducted in secret and there was little international financial governance prior to the collapse of fixed parity in the IMF, opportunities for participation were limited during the 1970s. Moreover, there were no federal statutes specifically subjecting the establishment and conduct of foreign banking operations to central bank supervision in the United States. Without it, there was no central repository for statistics to even know how many existed.Footnote 50 After the collapse of Franklin National and as the results of the Basel meetings became germane to domestic bank regulation in the United States, the international situation became more important to other actors in the U.S. foreign policy process. When pressed by interest groups and agencies, Congress became more assertive. The effects of the new system for domestic and international cooperation on capital adequacy regulation fed back into the international policy cycle during a series of crises both domestic and foreign during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

Congressional assertion: legislation and international banking

The earliest movements for some type of regulation of foreign bank operations had appeared in the late 1960s after the Joint Economic Committee in Congress requested a study of the issue. Senator Jacob Javits of New York, who proposed it, was not as interested in the lack of regulation of these banks, but rather in the lack of opportunity for these banks to enter the U.S. market where they needed state authorization for the branch or to obtain a charter to operate. The rationale for Javits’ concern came from his constituency. Two of the three largest U.S. banks at the time (First National City Bank and the Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A.) had sought to liberalize New York banking law in 1960 in order to liberalize foreign entry. Each had extensive foreign operations. These banks had an interest in supporting freedom of access to the United States for foreign banks insofar as their own foreign expansion was limited by foreign countries that would only permit U.S. bank entry on a reciprocal basis.Footnote 51 Attempts at legislation followed in the remainder of the 1960s, but none became law.

Hence, in the early 1970s, foreign banks held a unique position within the American banking regulatory structure. Like other foreign firms, they could enter the U.S. market by a direct extension of the foreign corporate entity as a U.S. office, or establish a separate entity—subsidiary banks chartered under state or federal law. Unlike industrial establishments, however, a foreign bank needed a license from a supervisory authority before it could engage in depository banking.Footnote 52 Therefore, other than the impact of the Bank Holding Company Act on incorporation of a foreign-owned subsidiary bank and some related provisions of the Banking Act of 1933 concerning securities transactions, there was no federal legislation governing foreign bank entry.Footnote 53

The FRBNY and FBG remained the primary representatives of the United States at the early BIS meetings, despite the fact that the OCC was the principal supervisor of national banks and their overseas branches. Spero details several reasons that the OCC was not invited to the Standing Committee meetings from 1975 to March 1978.Footnote 54 First of all, the Standing Committee had grown out of the concerns of central bank governors at the BIS—itself an organization of central banks. Secondly, in the fragmented American regulatory and supervisory system, the OCC had less power and status than the Federal Reserve. Thirdly, the rivalry between the Federal Reserve and Treasury in policymaking is particularly strong in the area of the management of international financial relations. Inviting the OCC might have been perceived as opening a door to the Treasury. Finally, an Acting Comptroller headed the agency from June 1976 to May 1977 and was not in a position to press for participation. Hence at the beginning, the Federal Reserve merely kept the Comptroller informed of the Standing Committee's actions. When John G. Heimann became the new Comptroller, he pressed for inclusion. The Federal Reserve dropped its resistance.Footnote 55 From March 1978 the OCC was included.

Regulation addressed both the domestic and international situations. Some legislative proposals circulated that sought to reform the entire system of supervision in the United States. The U.S. representative to the BCBS reported on these proposals to the Committee, particularly on the effect that they would have on the status of foreign banks in the United States.Footnote 56 The law, the International Banking Act of 1978,Footnote 57 provided federal regulation of foreign bank participation in domestic financial markets. Its purpose was to give foreign banking institutions the same rights, duties, and privileges as domestic banks, while subjecting them to the same limitations, restrictions, and conditions.Footnote 58 Two major provisions would propel later international initiatives with respect to reserve requirements and deposit insurance.

As the Basel Committee continued its work and further crises ensued, Congress became more directly involved. In 1983, when Congress was debating the International Lending Supervision Act (ILSA) in response to the international debt crisis provoked by the Mexican default of 1982, Fernand St. Germain (D-RI), the Chair of the House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, and his staff met with the Chair of the Basel Committee and later remarked that he thought its work should be less secretive.Footnote 59 When the FDIC sought to attend the meetings of the BCBS, its Chairman, Peter Cooke, resisted because he felt that the FDIC was not very involved in supervising international banks and that U.S. representation was already excessive.Footnote 60 However, ILSA specified that agencies are to use the Basel Committee to establish an international agreement on uniform capital standards. Moreover, the FDIC was to be a participant in this process. After an Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) was established, Congress acted again. The Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006 amended ILSA to include the OTS at Basel as well.Footnote 61

Agency involvement: the rules process increases participation

As the work of the BCBS progressed in the early 1980s, it turned to the issue of capital adequacy. Since then, it has issued three major agreements on capital adequacy (Basel I, II, and III) as well as several interim agreements. Although Congress directed the agencies to participate in the Basel process, the agreements reached there must still proceed through the rule-making function set forth by the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act (APA) in order to become law in the United States. This requirement is necessary because the U.S. Constitution gives the executive branch the power to negotiate treaties, which are ratified in the Senate. While regulators may make a number of informal agreements among themselves, they cannot make agreements that contradict existing U.S. banking and securities law. Moreover, Congress can step in at any time with legislation to change the process. In the case of the later Basel agreements, the agencies and interest groups have approached Congress directly with their concerns.

Capital adequacy is an issue that is both highly technical and extremely contentious because if a bank must hold more capital, it cannot make a profit on it by lending it out. Yet the less it holds, the more vulnerable it is to insolvency. Early attempts at quantifying capital adequacy in the United States were controversial and unsuccessful, albeit the National Bank Act attempted to set static minimum capital requirements based on the population of each bank's service area as early as 1864. When regulators did try to issue formal capital adequacy requirements, they were not uniform. They used a fixed capital to asset ratio, meaning that a bank held a given amount of capital against its assets, regardless of their level of risk.Footnote 62 When Congress eventually passed ILSA in 1983, it directed domestic regulatory agencies to establish minimum levels of capital at the same time they were working to establish an international agreement in the Basel Committee.Footnote 63 Therefore, attempts at domestic and international harmonization took place simultaneously so that standards would not disadvantage any one segment of the market with a given regulator.

When finally released on 15 July 1988, the first Basel accord on capital adequacy had two main sections, the first defines capital and the second elaborates risk weights. It set forth a “two-tier” definition of capital in which the first tier would comprise shareholders' equity, and the second would include other elements at the discretion of national authorities.Footnote 64 The system also permitted national authorities some discretion in assigning weights to asset categories. While the agreement may have moved in the direction of international harmonization, it provoked a turf war among U.S. regulators concerning how the new standards would apply. The problem centered on the risk-based capital approach, and the way the agreement treated U.S. mortgages since they were determined to be riskier than sovereign bonds. While sovereign bonds are more likely to be repaid than mortgages, they do have a degree of risk. The new rules threatened the FDIC's insurance fund because they would have allowed nine out of ten small banks to lower their capital cushion. The OCC wanted to use the Basel standard for sovereign bonds because it wanted the banks it regulates to be able to compete with foreign banks that would be using the lower standards. The Federal Reserve was not satisfied with the OCC's line, but compromised with the FDIC. Eventually, the OCC agreed with the FDIC-Fed compromise, but not until a lengthy delay caused a good deal of confusion in the industry about how the agreement would be implemented.Footnote 65

While Basel I had established the principle of risk-weighting in capital adequacy requirements and led to greater harmonization of capital held, that harmonization was far from complete. The actual risk weights assigned had been trouble from the start.Footnote 66 Member-states proposed to establish a new accord to replace the 1988 Accord, and remove distortions like the favorable risk weightings assigned to OECD countries' bonds.Footnote 67 Also of note, the Agreement had not handled the problem of residential mortgages in the United States, which comprised a large part of American financial sector activity. Thus, problems with the implementation led to an immediate need to amend the agreement, and eventually seek a new one.

During the process of negotiating the next agreement, disagreements among American regulators rose to the level that Members of the House Committee on Financial Services introduced H.R. 2043 in order to attempt to reach a common position on it.Footnote 68 Hearings were held in June of 2003 to air the concerns of the regulators and industry affected.Footnote 69 In 2004, the Basel II accord was published. It was structured around three pillars that address different aspects of banking regulation and that sought to reward banks that used more sophisticated risk management systems with lower capital requirements. Pillar 1 outlines capital requirements.Footnote 70 Pillar 2 addresses the supervisory reviewing of a bank's capital adequacy and internal assessment process. Pillar 3 proposes a wide range of disclosure initiatives that would enhance the effective use of market discipline to encourage sound banking practices.Footnote 71

Once again, implementation of Basel II in the American framework was a problem due to the diversity of banks and regulators, and despite the fact that the Federal Reserve finally took up its shares and appointed the Chairman of the FRBG and president of the FRBNY to its board in the intervening years.Footnote 72 Federal Reserve Vice Chair Ferguson announced that the United States would use a bifurcated approach—meaning smaller banks would be exempt from additional capital requirements and compliance costs. The overall level of regulatory capital in the banking system should have remained roughly the same. The capital reductions to take place would be tempered by maintaining a leverage ratio.Footnote 73 Initially, it appeared that the bifurcated approach would be acceptable to all parties. However, implementation called these suppositions into question. Some large U.S. banks objected to the persistence of a leverage ratio in domestic practice as contradicting the spirit of the intended capital reductions in the international agreement. The smaller banks perceived competitive advantages to accrue to core banks in adopting the new standards.

As the agencies worked to resolve their differences on Basel II implementation, another financial crisis hit. The largest U.S. investment banks either failed (Lehman Brothers), were taken over by commercial banks (Bear Stearns), or converted to commercial banks charters (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley). The largest savings and loan associations failed or were sold during the crisis (Countrywide Financial, IndyMac, and Washington Mutual). The mortgage finance system was likewise reshaped in the summer of 2008 when the government-sponsored enterprises Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA or Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Association (FHLMA or Freddie Mac) were placed into government conservatorship. Thus, the implementation of Basel II would need to occur in the new landscape while leaders immediately called for a “Basel III.”

In July 2010, the U.S. Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which eliminated the OTS as a regulatory agency, and thus changed the bureaucratic structure through which any Basel Accord must be negotiated and implemented. At the same time Congress passed the Dodd-Frank bill, banks regulators and central bankers met again in Basel to try to reach an agreement on capital requirements, now known as Basel III. Europeans immediately questioned whether the United States would implement the accord, if and when it would be reached.Footnote 74 The week after the bill was passed, the House and Senate banking committees announced that they would hold hearings on the Basel negotiations, lest the Committee conclude lower capital requirements than were initially anticipated.Footnote 75 Before an agreement has been reached, banks objected that the economies of the United States and Europe would be 3 percent smaller after five years than if Basel III is not implemented. A new debate has begun over the trade-off between the safety with the greater degree of regulation vs. the cost of a smaller economic growth rate.

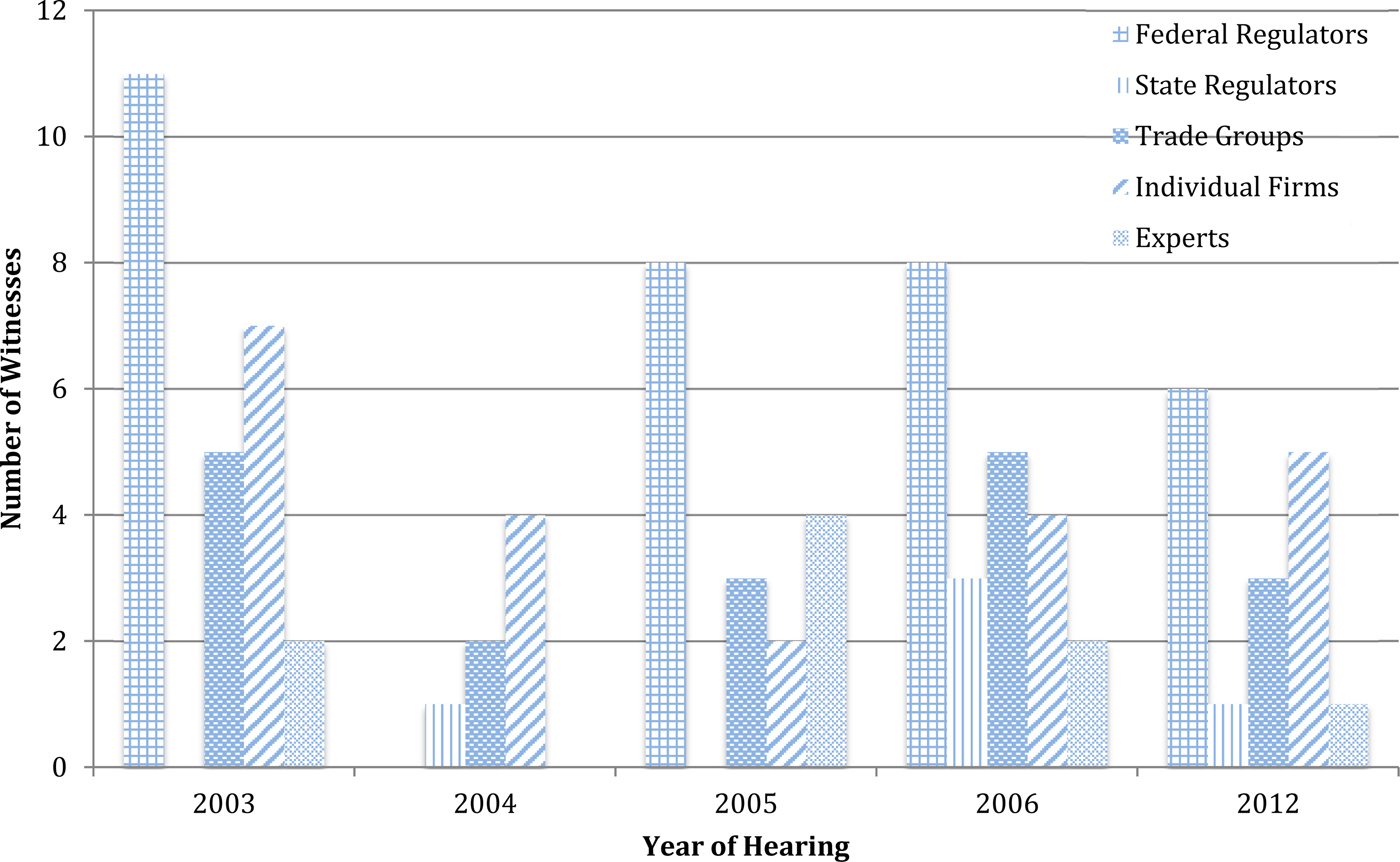

Therefore, as the process for reaching a multilateral agreement on finance matures, Congress has become more assertive when it perceives a threat to a segment of the American financial services industry. The APA process for seeking comments has drawn in a broader number of participants. The major political actors on these issues have also appeared before congressional committees to press for their interests with respect to an agreement itself, or how the United States is represented on the committee. In earlier years, activities at the Basel Committee were only mentioned in passing in hearings on related legislation. By 2003, Congress held hearings on the Basel Committee itself.

Rather than a wide set of inputs narrowing to a policy output as conventional models of foreign policy making would depict, figure 2 fleshes out how participation of types of regulators and groups has evolved at congressional hearings devoted solely to Basel agreements since 2003. Of the eleven hearings, federal regulatory agencies have provided the greatest number of regulators, even after the OTS was disbanded. Trade associations and individual firms are also well represented. State regulators became regular witnesses in later years. While there is overlap between the participation of individual firms and their inclusion in trade groups, figure 2 represents their category as stated on the hearing record. The trade associations with the most appearances were the Independent Community Bankers of America and America's Community Bankers with four and three appearances, respectively. In late 2007, the latter group merged with the American Bankers Association. The activity displayed in the figure is a sharp contrast to the relative absence of such activity in the previous twenty-five years of discussion of the Basel Committee in U.S. congressional hearings.

Figure 2: Congressional Witnesses at Basel Hearings

The upshot of these later and future cycles of the BCBS is that as the course of successive banking crises unfolded, jurisdiction over the foreign branches of U.S. banks became an important concern of American regulators at the federal and state levels. Given the new environment for all banks that were forced to compete internationally in a world of newly flexible exchange rates, the United States needed agreement at the international level over who would supervise what, and how. Individual firms lobbied on their own behalf, as well as through trade groups. Yet the United States also needed new institutional arrangements within the regulatory structure at home. Later agreements on capital adequacy (Basel I, II, and III) can be understood to reflect the similar need for the United States to coordinate regulations at both the national and international level, eroding the distinction between domestic and international politics and the distinction between the international monetary system and financial systems.

Conclusion

I have argued that the way the U.S. government acts internationally in the financial area has important implications for present responses to all international crises. The dynamics and expanded participation of domestic American political institutions are crucial to understanding the evolution of global financial standards. Yet this is not to say that the United States is the only country that matters in the international financial system this way. European foreign policymaking in finance is equally as important. Nor are the BIS or BCBS Basel Committee the only arenas for multilateral discussions of financial governance. Rather than offering a theory that is generalizable across states, I offer a refinement of existing understandings by digging into the American state. Ignoring the nature of U.S. domestic political and regulatory dynamics overlooks the important implications these dynamics have for the way the international system of financial governance works. The unique American political culture that operates here must be taken into account theoretically because the United States plays such a central role overall—both in terms of its influence in multilateral forums and volume of capital flows.