The Chairman (Mr O. Thoresen, F.F.A.): I am currently Chairman of the National Employment Savings Trust, and chairman of the Pensions and Long-term Care Steering Group, which has oversight of the Product Research Group, who we are going to hear from at this meeting.

Tom Kenny is Chair of the Products Research Group. He has been involved in the product design and pricing of retirement products for many years and since 2011 has been head of retail pricing at Partnership Insurance.

Paul Burstow served for two and a half years as a Minister of State for Care Services in the Department of Health during the Coalition Government, where he had an extensive brief, including care for the elderly, adult social care, mental health, cancer, diabetes and learning disability programmes. He was responsible for setting up the Dilnot Commission, which we will hear more about shortly, on paying for long-term care, reforming social care law, drafting the government’s mental health strategy, the return of public health to local government and the creation of health and well-being boards.

Since leaving Parliament at the 2015 General Election, Paul has chaired 2-year-long independent commissions, one on mental health with the think-tank Centre Forum; another on the Future of Residential Care with the think-tank Demos.

Richard Purcell is Head of Technical Marketing at Vitality Life, where his role is focused on helping to bring new protection products to the market. He is also an active volunteer in the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA), having previously been on the Health & Care Research Committee.

Currently, Richard is on the Health & Care Conference Committee and is also Editor at The Actuary magazine. We will be hearing from Paul and from Richard after we hear from the Product Research Group.

Ben Rickayzen started his actuarial career in pensions consultancy at Bacon & Woodrow (B&W), where he qualified in 1990.

After around 10 years at B&W, he decided to move into academia and took up a lectureship at City University London, where he has worked ever since. He has been Head of the Faculty of Actuarial Science and Insurance at Cass Business School since 2008, and was promoted to Professor of Actuarial Science in 2013. His main research interest is health, and long-term care in particular.

We also have Jerry Barnfield. Jerry has held a number of roles in the industry, most recently Group Head of Market and Product Strategy at Aquila Heywood. He is now retired and working as a volunteer adviser for the Pension Advisory Service.

Moving on to Linda Daly: she is an Actuarial Science Lecturer at University College, Cork (UCC). Linda worked as a pension consultant with Mercer for over 10 years and joined the university in 2012. Linda conducts the main part of her research in the area of mortality and morbidity studies as well as the funding of long-term care.

The question of how we deal with the funding for care in later life has been with us, it seems, for decades. It has been a subject I have been close to for much of the last 10 years. We all hoped that the Dilnot Report in July 2011 signalled the opportunity and potential for real progress.

In January 2014 Norman Lamb, Minister of State for Care and Support, signed the statement of intent, when I was director-general of the Association of British Insurers (ABI). We declared that the industry and government would work together to create the right conditions for a larger market in financial products in this area. Then, in March 2014, we had the Freedom and Choice Budget, followed in 2015 by the deferral of aspects of the Care Act, which had been built off the Dilnot Report, to 2020 at the earliest.

With the environment in which product and advice solutions need to work still developing and evolving, the need is still clearly there and growing. It is a great opportunity for the actuarial profession to shape the way that policy develops in this area, and the work of the Group is extremely valuable.

Professor B. D. Rickayzen, F.I.A. (introducing the paper – background and products): I begin by giving some background to the work that we have been doing. Then I am going to discuss insurance and other financial products we consider in our paper. Linda Daly is going to take you through the case studies that we produced in the paper. Finally, Jerry Barnfield will describe the results we have obtained from the modelling of care costs.

Originally, we were writing the paper on the basis that the Care Act 2014 would be implemented in full. In the event, the government decided to delay implementing Phase 2 of the Act until 2020. In particular, they announced last year that the introduction of the care cap of £72,000, and the new means test limits, would be deferred for those 4 years. So we have taken the opportunity to consider in our paper what the social care landscape would look like if those changes had been made. In other words, we hope the paper is going to act as a catalyst for policymakers to consider what changes should be made to social care by 2020.

I have been carrying out research in the area of long-term care since the mid-1990s and recall the discussions that took place on this topic when the Royal Commission was set up in 1996. There were many opinions about what should be done. One aspect everybody could agree was that the social care system could not possibly stay as it was. It is disappointing 20 years later that we seem to be in exactly the same position as we were 20 years ago.

This perhaps is not surprising when you consider the position of the main players in the social care arena; the individuals, the State and the private sector, including insurers. The individual is reluctant even to contemplate making provision for long-term care, since it is such a grim and unsavoury subject. There is also a lack of awareness around the topic, made worse by the complexity, which we illustrate in our case studies.

People hope that they will never need long-term care. So they feel that they would be wasting their premiums. With something like only a one-in-four chance of actually requiring care, they may well be right.

The State, on the other hand, is reluctant to make big, irreversible decisions on social care since the costs always come out looking so high. Hence the Phase 2 deferment to 2020. The insurance industry is reticent about devoting lots of time and money in developing products because they might not sell, since there is no certainty that a future government will not reverse decisions made by a previous government. So we live in this state of what I call “unstable equilibrium”.

Despite this “unstable equilibrium” we should not stop trying to develop products that might help people fund their long-term care: that cost will not go away just because we do not like thinking about it.

Turning to the work described in our paper. Our working party was set up about 3 years ago. We presented a paper in 2014 which analysed the way in which pension-type products could be adjusted to help long-term care. We were then asked by the Profession to consider more widely what kinds of financial products (i.e. not just pensions or insurance products) could meet the brief and we produced our paper. As we consider the array of products analysed in this paper, we need to bear two things in mind. First of all, it is not a matter of one size fits all; different products will suit different people, depending on their personal circumstances such as wealth, home ownership status, whether they have dependants, and so on.

Secondly, we are in a new paradigm with regard to the pensions’ freedom and choice agenda which came into effect last year. It is still too early to say how that will play out for individuals in practice.

So which products did we consider in the paper? I start with the products that we included in our 2014 paper and update the situation in the light of the changes that have occurred since 2014. We know that pre-funded long-term care products have not sold in the past. Had the cap of £72,000 been introduced, we felt that there might be a market for cover up to reaching that cap. However, with the cap being delayed to 2020, and many people wondering if the cap really will be introduced, given that 2020 is the year of the next election, the scope for pre-funded long-term care products seems very limited at the moment.

By contrast, income drawdown does seem to lend itself well to the concept of funding long-term care, particularly as a result of the new pensions’ freedom and choice changes.

In our previous paper, we suggested that some thought be given to introducing a pension care fund. This would be a ring-fenced long-term care fund set up within a defined contribution pension fund with attaching inheritance tax advantages as well as the usual tax advantages. However, with the new flexibility around pensions being introduced, the tax advantages of the pension care fund seem to have largely disappeared.

Disability linked annuities are products that we believe individuals would find attractive, as such annuitants would receive a standard annuity while they are healthy, but be reassured that the annuity would increase to a much higher level to help defray the costs of care, should they subsequently require long-term care. This seems to be an unusual long-term care product in that it has a positive spin to it. The fact that long-term care would not expect to begin for many years and would not expect to last very long, when it does begin, should make the extra premium payable relatively low.

An alternative to that type of disability linked annuity, which would have an even lower extra cost, is one which pays nothing while the individual is healthy but, again, a high level of annuity once the person requires long-term care.

Immediate needs annuities and variable annuities are well-established and I will not say anything more about those at the moment.

We explored the idea of introducing innovative non-pension products. For example, a few companies have started to introduce accelerated whole life products where an accelerated payment is made should the policyholder require care in either a residential or domiciliary setting, with the eventual death benefit being reduced accordingly. This product is aimed at people who wish to take out a whole life policy but are worried about the unexpected costs of long-term care, should it be required. Since the sum assured will definitely eventually be paid, whether it is triggered by death or by long-term care, it is a low-risk way for an insurer to enter the long-term care insurance market.

With such a high proportion of older people in the UK owning their home, we believe that equity release has a big part to play in the funding of long-term care. However, the ongoing review by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) presents a risk to the market that equity release products might become expensive, and therefore less attractive.

Apart from those existing equity release products, it is worth considering the UK Equity Bank product which my colleagues at Cass Business School, Professor Les Mayhew and David Smith, have advocated and written a paper about. Essentially, the State acts as the lender.

We have also described in our paper the concept of the Care Individual Savings Account (ISA). This would be an ISA where the fund was ring-fenced to cover only long-term care costs with the facility for it to be passed from one generation to another. There were rumours that it would be introduced in the recent Budget since a strong advocate was the Pension Minister, Baroness Altmann. In the event, a lifetime individual savings account was introduced instead, which is aimed at helping people under aged 40 to build up their savings, but not specifically with long-term care in mind.

A final product that we mentioned is aimed at people who have only a basic pension and modest savings. This is the Personal Care Savings Bond and is an idea developed, again, by Prof Mayhew and David Smith. It is like a premium bond with monthly prize draws, but would earn a small amount of interest and pay out once long-term care was required. This product seems to tap neatly into the lottery mentality that we all seem to possess.

I will now hand over to Linda Daly, who is going to discuss the case studies we have produced. These illustrate how complicated the current social care payment structure is.

I end on a thought-provoking note. A recent survey commissioned by the IFoA disclosed that about half the respondents had considered long-term care costs, but only 4% of the respondents had made any kind of provision. Clearly, there is much work to be done in convincing people to think about their future long-term care needs.

Miss L. M. Daly, F.I.A. (introducing the paper – case studies): As part of the working group analysis, we decided to develop a number of case studies to illustrate the complexity of the system and in particular look at how the proposed cap of £72,000 and the new means test limit would work in practice from 2020, when all aspects of the Care Act are in place.

In our report, we looked in detail at three people with different financial backgrounds. I am briefly going to lead you through two of the three examples contained in the report.

The first example is Susan. She is married. She enters a care home costing nearly £33,000 pa of which £12,000 is the daily living cost to cover the basic essentials like heating and food. She has an income of £21,000, which includes a State pension, and a private pension, and she is also in receipt of the National Health Service (NHS)-funded allowance (included in that sum). She qualifies for the NHS-funded allowance, but we have assumed that she does not qualify for the attendance allowance (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Example – Susan

Her home is jointly owned. It is valued at £200,000. The couple have combined savings of £50,000. The reason we picked this example was, we wanted to illustrate the case where the home is excluded from the financial assessment that somebody is required to pay, given that her husband is still living in the home and of their combined savings just 50% of the savings are taken into account in the financial assessment of what Susan is required to pay.

The bar charts on Figure 2 lead us through how the funding of her care costs are formed before and after the cap.

Figure 2 Progression of care costs for married person jointly owning home valued at £200,000 with £50,000 of joint savings

In the first column we have the local authority set rate, which is the first component of the cost of the care home. On the top of that there are the daily living costs. That brings us up to the figure of £33,000, which is the cost of Susan’s care home. We have assumed that she is going to enter the care home.

In the 1st year, she is going to use her State pension, her NHS-funded allowance and 50% of her private pension to fund the cost of care. You can see the State pension less the personal expense allowance. She is entitled to keep £25.77 a week for herself. But, other than that, the rest of her income is to fund the cost of care in the 1st year. Also, she has to contribute a portion of her savings. Her savings are deemed to be 50% of the combined savings of her and her husband, that is, £25,000. We call the proportion of savings she pays the tariff income. There is a fixed formula for calculating it, which says for every £250 you have over £17,000 in savings, you need to contribute £1 a week. That actually works out at over £1,600 in the 1st year. That is the first make-up of the care costs.

There is a funding gap, so the local authority contribution will apply, because under the means test she has paid what she can, and they must fund the balance.

A similar picture arises in the 2nd year. She is going to pay a little bit less tariff income, because her savings are gradually diminishing as she is paying out a portion from them that keeps going for approximately three and a half years, when £72,000 has been contributed towards care. After that, the cap kicks in, but she still needs to pay for her daily living costs going forward with the local authority contribution applying to fund the balance. So, as long as she meets her daily living costs, the local authority will fund the balance once she has reached the cap after three and a half years.

The key thing from this example is that it shows when the home is not taken into account under the means testing limits, because her husband is currently living in the marital home and so it is excluded from the financial assessment of what she is required to pay.

The next example we looked at is a relatively well-off individual. Her name is Mary. She is single. She is going for a more expensive home than the previous example. Her care home costs nearly £43,000 a year, which again is made up of the local authority rate of £33,000 including the £12,000 daily living cost, but as her chosen home is more expensive home, she pays another £10,335 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Example – Mary

She again has an income of £21,000 a year, made up of her State pension, a private pension, the NHS-funded allowance and we have assumed the attendance allowance. She owns her home mortgage-free, valued at £200,000. She has £30,000 in savings.

This person is single and because she does not have a spouse living in her home, it can be taken into account in the financial assessment of what she is required to pay.

We looked at two scenarios for Mary. First, we assume that she does not use her home effectively as collateral under the deferred payment scheme. The second example is where we assume that she enters into the deferred payment scheme.

We prepared bar charts similar to the previous example, with the care costs in the first column. The first component is the local authority rate, then the daily living cost of £12,000 and finally the excess over the local authority rate, the Top-Up cost (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Progression of care costs for a single person owning a house valued at £200,000 and with savings of £30,000

In the 1st year, we assume that she pays as much as she can. She uses her State pension, the attendance allowance, the NHS-funded allowance and the private pension. As a relatively well-off individual, she has to use her savings to fund the balance.

In year 2, it is a similar picture, but her £30,000 of savings are depleted and have run out. Then we assume that either a family member, or some other third-party steps in, takes the burden of the balance, the shortfall top-up payment. This funding is going to continue for about three and a half years at which point Mary, or the third party, will have contributed £72,000 based on the local authority rate. The £72,000 cap does not include the daily living cost or the top-up cost. It is just based on what the local authority would pay towards nursing care. We assume that £72,000 is reached in about three and a half years. After that, Mary or the third-party is still responsible for paying the daily living costs and the top-up costs, but the local authority contribution kicks in because she has reached the cap. That stays in a steady state from that point on.

That is an example assuming that she has a third party to cover her bill. If she does not, Mary can take out a loan against her house, which we call the deferred payment scheme.

Using the same costs, and again assuming that the costs of the nursing home are there, the total costs are £43,000 a year. The funding in the 1st year is the same as she pays as much as she can with her State pension and attendance allowance, her private pension and her savings. Again, her savings run out in year 2, at which point there is a shortfall. As she is living on her own, her house can be taken into account in what she is required to pay. She basically enters a deferred payment scheme where she takes a loan out against her house, which will be repaid when Mary is deceased and her estate is sold.

In the 3rd year, when no savings are left, she has to take out a bigger loan. The gap is a little bit bigger.

By year 4 she continues to pay as much as she can but the local authority contribution kicks in because the £72,000 cap was reached after three and a half years. In year 4 the cap is implemented in full so she does not have to borrow as much against her house. So the Deferred Payment Option block shown on Figure 5 starts getting smaller from that point on because the cap has kicked in. She does not need as much of the loan against her house.

Figure 5 Progression of care costs for a single person owning a house valued at £200,000 and with savings of £30,000 using the deferred payment option

The Deferred Payment Option loan grows with the balance required and with interest if it is not paid back. The bar charts show how the loan progresses over the first 5 years. The difference is quite big in the 1st year. She does not need any loan in year 1 because her savings have been used. In year 2 and year 3, there is quite a big jump. In year 4 and in year 5 that gap starts getting smaller because she has to borrow less, given that the cap has kicked in (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Progression of deferred payment loan for a single person owning a house valued at £200,000 and with savings of £30,000

We chose this example to demonstrate how the care cap and the means testing limits would work when somebody’s house is taken into account.

There is a third example in the report for somebody living in rented accommodation as well as more detail for the two examples. I hope these have illustrated how complex the new system is.

Mr J. K. Barnfield, F.I.A. (introducing the paper – modelling aspects): Within the working group I worked on some of the modelling that we have developed over the last few years. These include modelling the costs of care, the likelihood of needing care, the probability of reaching the care cap, the regional variation of some of the results and the incentive to save for potential care costs in future.

Some of the modelling work is an update to the work that we did in 2014 with more up-to-date data, while the “incentive to save” modelling is completely new.

I will start with a recap of the detailed modelling that we carried out in 2014.

Figure 7 shows whether individuals entering care homes at various ages are likely to benefit from the £72,000 care cap that is proposed to be implemented in 2020. The results indicate that, given the assumptions set out in the paper, females entering care homes at the average age of 85 have a 14% probability of reaching the cap compared with 8% for males. The vast majority will not reach the cap because they will not survive long enough to do so.

Figure 7 Approximate probability of reaching the cap by age & gender

Linda (Daly) went through some of the key components of funding care costs. It is important to recognise that some of the components vary by region, especially the care home costs and the local authority set rates. This results in significant variation in the probability of reaching the cap, and the length of time before reaching the cap.

Individuals in care homes in London and the South are likely to have a higher probability of reaching the cap and in a shorter period than those in other regions. This brings up questions as to whether there should be a regional care cost, as currently, or whether there should be a standard rate across the country, like the daily living costs, and the attendance allowance and NHS-funded allowances (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Personal funding of care costs by region in England from 2016, care home with nursing – 85 at entry into Care

One of the major challenges that we have to address is the incentive to save for potential future care costs. While we recognise that State provision of social care needs are subject to a means test, it does mean that for many individuals there is no financial incentive to save for potential care costs. Some individuals will save for long-term care needs so that they can influence the type of care or the quality of care that they receive, or indeed the location of a particular care home.

For financial incentives, our model demonstrates that the current means testing approach is a significant disincentive to save. The changes in the means test proposed for 2020 would reduce this disincentive, but there would still be a significant disincentive to save. We believe that further changes in the means test should be considered before 2020 to reduce the disincentive to save.

Figure 9 looks at the impact of the current means test on saving. In the model we look at what happens if an individual decides to increase their level of saving by an additional £10,000 over and above the savings that they expect to have at the point of entering care. So, for example, say an individual expects to have £40,000 in assets at the point of entering care, what would be the impact of their personal contributions to the care costs if they save an extra £10,000 before entering care?

Figure 9 Increase in personal costs from saving £10k towards care costs (Current Means Test)

The total care costs payable by the individual over a 10-year period would increase by a bit more than £12,000 as a result of the £10,000 increase in saving. This means that saving the extra £10,000 has resulted in the extra saving all being taken away as a result of the reduced means tested benefits. This is a bit of an extreme example as only 1% of those in care are likely to be in care for a 10-year period. But the point remains.

Figure 10 shows an equivalent analysis for the Care Act 2014 means test limits, which are scheduled to be implemented in 2020. It shows that there is a greater incentive to save under the new system. In this case, a person expected to have £40,000 at the point of entry in care who saves an additional £10,000, finds their total care costs payable over a 10-year period increase by £8,000. So the individual actually has £2,000 left over to spend. While this offers a greater incentive to save than the current means test limits, the individual is still losing 80% of what they have saved as a result of the means test.

Figure 10 Increase in personal costs from saving £10k towards care costs (Care Act 2014 Means Test)

Overall, we believe that there could and should be more done to increase the incentive to save for potential future care costs.

Our conclusions are

-

1. A year after the introduction of “Freedom and Choice” for pensions it is still too early to understand exactly how individuals will respond to the new freedoms.

-

2. The care funding system is very difficult for people to understand. While the proposed changes in the Care Act in 2020 would be beneficial for consumers, it will make it even more complicated.

-

3. The current means testing system can cause a disincentive to save with an effective “tax rate” of over 100% for some people. The proposed changes to the means testing system in 2020 would reduce this disincentive but it will still exist, whereas we really need individuals to be incentivised to save for their potential care costs in future.

Our recommendations to address these issues are set out in the paper and Tom (Kenny) is going to refer to these.

Mr P. K. Burstow (opening the discussion): The paper sets out the history of many, many fruitless attempts to try to address some of the perceived unfairness within the current arrangements for paying for long-term care. All of those have one difference from the reforms that this paper talks about, the 2014 legislation. For the first time ever, we have a new legislative framework that provides a basis on which the level of the cap can be determined and the level of the threshold for means testing can be determined. That is a significant shift and a significant opportunity.

There are two reasons that the government chose to “postpone” the decision to go ahead with the implementation this year. One was the continuing absence of new significant products coming on to the market. My counter to that is: how would you expect a market to respond when there has been so much uncertainty historically? The government’s decision to postpone has created yet more uncertainty, so why would the sector deliver a new product?

The second, was a question about the overall funding of social care in this country and a suggestion that if the introduction were postponed, some additional money would come into the adult social care system as a whole. However, there is not much evidence to suggest that the Treasury has repurposed the monies that were earmarked towards the end of this parliament for that particular purpose. Certainly, there are significant pressures in the system.

The recommendations in the paper are all very sensible. The need for an awareness campaign, should the recommendations in the legislation be implemented, is necessary.

The proposals around data collection make sense and will provide a better understanding between industry and government. This discussion about new incentives makes sense and is heartening in terms of the analysis with respect to the current system and how the new system would work.

One of the reasons for introducing the cap was not just to protect assets, not just to protect people from the risk of catastrophic cost, it was also to effect a change in terms of behaviour with respect to people engaging with their local authorities and planning in a more long-term way for care costs and for the meeting of their care needs.

In other words, placing a whole part of our population who are self-funding much more clearly on the radar of local authorities; and by placing them on the radar of local authorities, engaging one of the duties that sits within the Care Act, which is to prevent and postpone the need for care. In other words, it would create the opportunity for public health interventions, for a sensible conversation to take place at an early stage with people about how they manage their care journey, but also how they perhaps minimise the need and the risk of going into more expensive end of life care.

The biggest missed opportunity is not bringing in the legislation, as it is a benefit that would have been gained very early, whereas the cap as is a benefit much later in the life of the legislation.

Returning to my point about the government arguing that part of the reason for postponing was to help with the stabilisation of the social care system as a whole in terms of funding. We have had one parliament where there has been a significant reduction in spend by many local authorities on their adult social care commitments; and it is now forecast that by the end of the current parliament we will have halved the proportion of GDP that we spend on long-term care in this country from 2% to around 1% of GDP. That will have profound implications not just for the viability of the publicly-funded marketplace, it will have significant implications for the overall viability of the marketplace for care services in this country. There are many providers who already speak to those points.

It is also accelerating the bifurcation in this market: those that are funding and being provided for in completely separate service provision models compared to those that are State-funded. For a whole series of reasons the paper is a helpful contribution. When the announcement was made last year that there was to be a postponement, it almost caused no ripples at all. It did not seem to cost the government much politically. That may be partly because of the complications of explaining what this is about; but there is still an opportunity during this parliament to make it a political issue, both in terms of the funding of the whole system, which has to be front and centre, but also the equity and fairness questions that the Dilnot Commission was tasked to try to address and did provide I believe an elegant solution to.

Mr R. E. Purcell, F.I.A. (advising on care: bridging the gap): My perspective is as one of the insurers that has brought to market a new solution which is referred to in the paper as an iterated whole life policy for long-term care, so essentially allowing people to use their protection policy and access that cover early should they need it in later life.

I thank the product group for their work and support their recommendations. The point about complexity is perhaps the most significant one and the call for more education is very important. This is where we have a massive challenge as a country. A national awareness campaign will be valuable. Also, there is a very important role for advice.

I am going to share with you a few observations that we have had in launching a new proposition through advisers; some of the challenges that we have had and some of the research that we did with consumers and advisers.

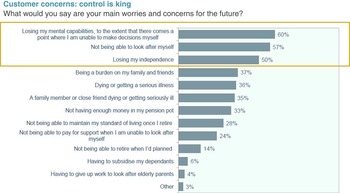

Some of this is not particularly surprising; but we asked customers what their concerns were when they are thinking about planning for care later in life. Unsurprisingly, remaining in control is top of the list, whether it is being able to make decisions, looking after yourself or remaining independent. That is important in thinking about our product design. What do we bring to market? What are our customers ultimately trying to do when they are thinking about the future?

The other point is around customer mindset. We found quite a wide range of mindsets among customers. One represents peoples’ own experience; people in their 50s or their 60s who have seen their own older parents go into care. They have had first-hand experience. That was very emotive but they could see that need more clearly (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Customer concerns, based on research commissioned by VitalityLife, 2014

At the other end of the spectrum there was a group of people who try to ignore the future need. They view themselves as being young at heart, carefree and did not really care much for planning for the future. Trying to address that group of people is going to be particularly difficult for the whole industry.

The need for advice was also interesting. How do people expect to pay for care? Again, some expected results: expecting that the State would pay came out top. Interestingly, 23% thought that they would not be able to pay for care at all using personal savings and investments. We need a bit of education there. The State might pay but, as we have seen from most case studies, there is a lot of complexity around when or how much it will pay (Figure 12).

Figure 12 The need for advice, based on research commissioned by VitalityLife, 2014

Also, there is need. Our assessment of what people are likely to need suggests that 40% will be in some form of financial difficulty in later life.

Looking at the advisers; we are a protection provider, selling most of our products through the advice channel in the UK. That is, what we see as a challenge in creating and bringing to market a new solution. I have tried to estimate how many advisers are qualified to advise on full long-term care. That is defined as the CF8 qualification, which is about 2.5%. This means that whilst we have many advisers, not many of them are qualified to talk about the full set of existing care products in the UK.

We have created a protection product which does not fall under that traditional care banner and therefore advisers do not need to be qualified: advisers seem to lack the confidence to talk about the whole subject. A couple of quotations from advisers shows us current thinking, “It’s one of the greyest areas of financial planning as there are no rules” and “I haven’t had the discussion with my clients about long term care because there isn’t a product on the market. Unless you talk about savings or investments”.

I disagree with these quotes, as there are a lot of products available. The industry needs to help the advisers understand what there is; and what they can be doing for their clients. We have gone through the process of trying to work out how we can help advisers better understand that journey. We believe there is an uphill struggle to help advisers, as well as customers, think about their needs and how we think about it.

There are a lot of solutions to help close that advice gap. A public awareness campaign has been mentioned and that would be valuable to help increase demand for advice. There are also more innovative ways to pay for advice being considered, for example, proposals around the pension advice allowance, which would allow people to draw down from their pensions to pay for advice and also using advice vouchers. That sort of remit should also broadly cover advice on care.

The next question is how to improve the supply of advice in the country. There is much welcome discussion about guidance at the moment with changes to pensions advice and also about robo-advice. We need to think about different forms of advice for different parts of society. We already have about 22,000 advisers in the country, so we have a massive footprint of advisers that we should be working with and leveraging to improve education. That is why I support the industry working more closely with the adviser community to help them get out there and talk about care needs with their clients.

Mr J. Constantinou, F.F.A.: I am a member of Council of the IFoA. Your first paper set the grounding for this paper and you have carried it forward very well.

However, you make no mention of compulsion as a means of stimulating the market. I would contend that there are sufficient overseas examples that demonstrate that that might be an interesting way of kick-starting a market.

On the opposite side, we have not had long-term care products for a long time, yet people have got by. Why should that change going forward?

Mr Burstow (responding): The question of compulsion was not something we asked Dilnot to look at. We did debate it in framing the terms of reference for his work. We did draw some analogies with the pension arrangements that have now come in and the “payroll giving” that takes place that way. There was some at least internal contemplation as to whether there was an opportunity to build something into that system. Maybe that would have been a better, tidier, more complete way of addressing it.

It partly reflects the fact that the development of pension policy and the development of social care policy and the funding of social care has tended to be developed largely in silos, even within government. Although there has been some cross-discussion, there was not a sufficient desire in the last government to make that a centrepiece reform. That is unfinished business and certainly something to come back to.

As for, people doing without insurance style products “the absence of any solution has not hurt anyone” is perhaps a rather crude summary of that.

I would contest that as it has both hurt in terms of the very obvious goal, which was around protection against catastrophic costs, but also in a more subtle way, the psychological shock that people sustain when they learn that this is a system that is not free. We have heard that 36% of people still think that it is going to be paid for by the State. Conflate that with the National Health Service and you have angry and frustrated people. It is underscored by the sense that people save and are not rewarded for that saving by the system but are penalised.

The issue now is one that to not sort this issue out risks sorting out the bigger question of how we sustain a social care system being pushed off the agenda.

One of the benefits of having implemented a cap, if it had come in from this year, is it would have brought into the system a whole group of people who would have been alerted to the fact that we have an inadequately funded, poorly operating care system in this country. It would have created a much greater lobby for investment but also for reform of the whole system, as well as the public health gains that I was talking about earlier on, which appear to have been lost.

People here and at other gatherings, are concerned and we have a role to play in creating the noise in the system. Whether it is an informed policy framework, detailed work of the sort that you were doing, we need that noise and agitation, and stating that there is a political cost for not doing anything.

The message that the Chancellor gave last year is that there is no political cost.

Mr T. P. J. Kenny, F.I.A.: On the compulsion point, we touched on incentives and we did a lot of analysis of that, particularly around means testing and tax policy. But we have not really gone into any depth. It is definitely an area that the profession should look at, as well research around sustainable funding models.

The other point about there being no products in relation to the whole issue of social care funding is that it is becoming more and more important. Our profession is probably one of the best positioned in the country to see the demographic issue that is in front of us. The population that is affected by social care policy is going to grow dramatically over the next 20 years.

In our public interest role, our profession should be informing the debate, making people aware and making government care about it. There should be a political cost to not having it high on the agenda.

Mr J. G. Spain, F.I.A.: I am a defined benefit pensions actuary. This paper is really about demand, whether it is met by the consumer or indirectly by the consumer through insurance of some sort or other provision.

But what about the supply? I am looking at example one, some £32,000 a year, which buys very little in the south-east. I recall a company, Southern Cross Health Care, which became insolvent a few years ago. We also need to look at the supply of care because some care homes are absolutely awful. If dogs were treated like that, there would be a problem politically. But for people, it does not really seem to matter.

Mr Burstow: Your point about supply underscores the point that I have been making. This is a market – I am talking about a provision market here – in which still the vast majority of it, and in some regions almost all of it, is dependent on the State funding that comes into the system.

If you are in the South East, yes, the premium to come into the system is higher and you are paying it yourself. But there is a bigger and more viable private market. If you are living in the North East, the private market is very small. The numbers paying into it are very small relative to the South East. Its viability, without a viable State sector, is much, much diminished.

So this is a question that affects more than just those who are the direct beneficiaries. As the example showed, there are people who have a mixture of different funding. Many more people are contributing indirectly through top-up payments to their provision as well as the State. The question of supply is absolutely at the heart of any debate about how we privately pay for our care, and the contribution the State, through the taxes we pay, puts in as well.

What we have seen, particularly in the last decade, is a decoupling of public funding for care being related to demography. By the end of this parliament there will be implications for many families, who will no longer have an easily-available care option available to them, and informal family care will have to be the backstop and shoulder a greater share of the burden.

Mr J. Instance, F.I.A.: I was taken by the complexity argument of care costs but also worried with the focuses on the different products and the possible complexities. As a profession, we have a public interest in explaining the need and how things work.

What do people need? If they have a house, they can choose equity release, and we can possibly improve on existing products. Otherwise, they are going to need to find other sources for cash. New freedom and choice for pension products provides one source of cash as does an ISA or other savings. George Osborne suggested different types of ISAs such as care and lifetime ISAs. I believe these are efficient tax-free savings products already available to fund care. We should be spending less time on developing new products and more time promoting these products and keeping things simpler for people to grasp.

Industry has always been very good at creating complexity, but we need to make life a lot simpler. That would make it easier for people to understand and grasp the issues. I would be interested in how we, as a profession, can lead that reduction in complexity argument.

The Chairman: One of the things that we can do is to help people begin to come to grips with how the system actually works or how it is proposed to work. I have heard the presentation on the case studies probably two or three different times in different forms and am now only finally starting to understand.

Not every man or woman in the street is going to be willing to give it that time. For me, the challenge is how and when should you engage with people in trying to get their attention on this subject so that they can begin to come to grips with what is involved. In the end it is adequacy, which is a large part of the discussion; the adequacy of the savings that have been made.

Mr Kenny: I totally agree that simplification is always something to aim for, particularly when you are trying to develop products. As has been highlighted by Ben, there is not really one product that fits all. It really depends where the person is in their savings and their life. Are they pre-retirement? Are they in retirement? Are they at the point of need and just going into care?

You can possibly reduce it down to three products for the different stages of life. I do not think that you can get away from having more than one product. Also, certain people are willing to take on different risks.

As an individual, if you understand it, are you willing to take on longevity risk? If you are, then you might not buy an annuity. But if you are aware of that risk, you might actually decide to buy an annuity, particularly if you are about to go into care and you understand the possible variation in life expectancy at that point in time. You might think it is quite a good thing to buy an immediate need annuity because it actually provides financial certainty for your loved ones – it is usually the loved ones who are making decisions at that point through power of attorney.

I agree it is complex and we are potentially proposing to make it even more complex by offering a wider range of products to ensure all bases covered.

The Chairman: Paul, could I ask you to develop this a bit? It strikes me that the challenge we still face is that people have not really got a sense of what the State does provide, and what their personal responsibility is.

I have been involved in this subject for some time. Governments are not always good at being absolutely clear about how a system can work and what personal responsibility the individual has to take. Do you think that that is part of the problem? Do you think that might change?

Mr Burstow: That brings us to the point that the first presenter, Ben, was saying about the idea that this would be introduced in 2020 – an election year. The decision to implement it in 2016 was very much for that reason because, although an implementation of the Dilnot system would have been a significant advance on where we were, it would have still raised a whole set of questions. It was not the actual amount that the individual was to pay, but the amount that the local council had to notionally set as what it would pay.

This scenario is political: you then have a new postcode lottery of different local authorities’ determinations, some which can be justified and some which cannot. The desire to delay was partly driven by those complexities and a fear of how you would explain some of those things.

I believe it would be helpful to still have to explain those things and strongly support the recommendation of awareness-raising. Access to good information and local authority signposting are aspects that some of us argued for during the passage of legislation along with the concept of not just hand-outs from the local authority to other agencies. There ought to be much more of an informed discussion to make sure people did actually avail themselves of more advice to facilitate their plans.

I confirm that the benefit of creating a care account and applying to be registered to have a care account, which is the mechanism for clocking up entitlement to the cap coming in, was an opportunity to prevent and postpone need, but is now lost. Consequently, costs will increase for all. It was also an opportunity for the local authority to prevent people falling back on public resources by actually having an early conversation and signposting into the necessary financial advice that would enable people to start making financial plans.

We know from some of the products that have been in the market for some time that, where those are available, they can avoid people falling back onto State resources. It can actually save the Exchequer some money as well.

Awareness is absolutely critical. I welcome what Tom was saying earlier about the profession’s public interest duty not to be political, but to be very clear at helping in the general public discourse about these issues. This will go back up the agenda during this parliament and the profession’s voice setting out dispassionately the evidence will be very important to moving this agenda forward.

Mr D. B. Martin, F.F.A.: The topic is fascinating. A combination of more interesting products and communication education is obviously required. The whole of life after retirement needs to be considered in the new products.

There is a U-shape that people follow at the early stages of retirement. Their need for finance is quite high initially because people are still healthy enough to be able to enjoy life, go on nice holidays, and so on. It dips down typically throughout retirement. Some people drop off the scale at that stage. Others, however, go up in their expenditure substantially at the end of life.

I have experience of this with my parents, one of whom died before that extra cost was required, and the other one was much later. It really is quite a puzzle to know what to do. Some useful thinking is required as to what sort of products might be available.

There was mention in the presentation about the low cost of the deferred annuity type that might be required in the case of ill-health and that will be useful.

We should look at it in the context of the whole of retirement and not just the very end.

Mr Kenny: The point around retirement needs, the profile, the U-shape, (and there are possibly different shapes, depending on your own attitude to lifestyle and that sort of thing) goes back to points around potentially different products for different people.

For someone who wants to live for today, maybe they will want to have a drawdown product and are willing to take on the investment risk and the longevity risk associated with that, assuming that they are informed of those risks. Perhaps that is the product for them. If someone wants to get rid of all financial uncertainty, perhaps they will go for a disability-linked annuity, if that is made available in the market. If someone is pre-retirement, perhaps they will go for a pre-funded protection product.

It really depends on the person, their attitude to risk and their understanding of the different risks.

Coming back to the complexity point raised earlier, perhaps one of the obvious answers to solving the complexity point is for the government to provide a solution. But that would be going back to the question Jules asked around compulsion. That is not something that we have been looking at. I cannot see getting away from the complex system unless you take the responsibility away from the individual.

The Chairman: Linked into the broader discussion on freedom and choice in pensions, do you think we will see a significant growth in the deferred annuity market in the UK?

Mr Kenny: I believe so. It is potentially quite an attractive product. Once people are made aware of longevity risk, and we are starting to do a lot in that area to raise the profile of it, providers will come out with products that perhaps bolt on to drawdown products.

Mr Burstow: One final observation is how to frame the debate about how we pay, as individual citizens, for our long-term care costs and the wider question of the sustainability of our health and social care systems.

Some arbitrary decisions were made in the 1940s about how the line was drawn between health and social care. That line has moved in an ad hoc way, in a piecemeal way, not a way that has been subject to much public debate over the last 60, 70 or 80 years. My colleague, Norman Lamb, who succeeded me as Care Minister in the Coalition Government, with support across parties, has been advancing the notion that we need to address – whether you call it another Beveridge, or whether you call it an independent commission with Government support – some of those really awkward questions about why it is that someone with dementia finds themselves in the social care system picking up most of the costs of that unplanned-for-condition, while someone perhaps with a cancer that is the result of smoking has all of their costs picked up by the State.

Those issues of fundamental equity do need to be reopened in order actually to design and create a fair and sustainable tax-funded system as well as identifying those things where the individual should bear the risk and fund their costs themselves.

Mr Purcell: One of the points that has come up again in questions is around how products can add complexity and agree with that to an extent. Part of that is down to the need being complex. Different products doing different things. The need for care is a complex one against complex State support. To an extent that that can be simplified, then that will help, and then the products that we develop become simpler as a result. Those things probably are not going to change any time soon.

The opportunity, possibly a big one, is how we can help customers understand the options and maybe the development of more tools to look at all the different options and what works for different risk appetites and profiles of people. This is the front end, not at product level, but more the holistic kind of solution.

Mr T. P. J. Kenny, F.I.A. (closing the discussion): Picking up where Jerry left off, I will highlight the recommendations that we made in our paper. Then focus on some of the elements that have been covered in the debate.

One of the recommendations that we made in our paper was that there should be a joint government and industry approach to collecting data on how people are responding to the new system, and that will help to assess whether education in the use of default retirement options, or incentives for long-term care products such as tax relief and employer contributions could be effective in helping people to use their savings to meet care costs.

Another recommendation, which we have already touched on, was around the national awareness-raising campaign. That will help people to understand what their potential care costs might be, what State support is available, and possible products that might protect them from having to make a decision at the point of crisis, which is often the things that we hear about when we have these debates around care. Many people do not realise or understand the system.

The third recommendation was around how to incentivise people to save. Assuming that we have this model where individuals need to save for their care costs, what could be done to incentivise or to increase the incentive to save?

One of our recommendations is that there could be a new product or category of products that allow savings to be exempt from the means test up to a specified threshold. That would increase the awareness of care funding because product providers would promote those products. The government would make people aware of the products.

The costs of introducing this new exemption could be met by removing existing loopholes which are not widely made public, but a lot of advisers are aware of them. One of them is that investment bonds currently are exempt from the means test, as are some life insurance products, which means that if people are minded to do so, they can place significant amounts of assets in those vehicles and can still qualify for the means test.

Those are the three main recommendations from our paper.

Picking up on some of the points from the debate, as Jerry highlighted from our analysis in the paper, regional variation is a big factor in care funding. There is variation in actual cost of care; there is variation in the way that the new Care Act is actually applied to individuals in the different regions. There is also regional variation in the supply and the split between self-funders and local authority-funded individuals. Regional variation is a very important point and there is no easy answer to that one. Perhaps that is something which we, as a Profession, could help to provide an answer to, given that there has been a deferral of implementation.

Compulsion: that is a very good question and that should be revisited as part of the research that the Profession is doing at the moment on sustainability of funding models.

Complexity: we have made the point in our paper around the fact that the system is very complex. We need a way of informing individuals about how it works so that they are given the opportunity to save for their potential care costs; but also we need a way of doing that which does not completely confuse people and put them off dealing with that at all. That is a difficult one to solve in itself.

Supply of care: someone raised that point. Is there sufficient supply of good quality care homes in the UK? I guess from what you see in the media that the answer probably is that there is not. Again, going back to the demographics, you have to think that if you are a supplier of care homes, you would think it is a great opportunity to build new care homes as long as the funding works. That goes back to “where?” I can imagine in the south-east, where there are a lot of self-funders. That is a very attractive place to build a care home. In the north, where it is mostly local authority-funded individuals, perhaps it is not so attractive. Maybe more needs to be done about that, otherwise there is going to be a geographic variation in the quality of care, which is obviously not ideal.

Those are the main points.

The Chairman: I was struck by something that Paul said which was that as this Parliament goes on, as we begin to approach the next election, it is clear that this subject will begin to move up the agenda again in terms of political focus. For me that has always been a significant opportunity for the profession to give an objective point of view on a subject for which it is very difficult for the policymakers to find a sensible destination, and where our contribution could be extremely useful.

I would encourage the group to keep working; I would encourage anybody in the audience who is interested to consider becoming involved in some way.

I should like to thank the contributors and all the speakers and the panellists, and particularly those who have been involved in the group for the excellent work that they have done. I encourage you to carry on with it and look forward to its development over the months to come.