1. INTRODUCTION

One of the main research fields of the Japanese Association of Sociology of Law (JASL) is the legal profession. Even in the Journal of Sociology of Law,Footnote 1 this subject has repeatedly been a special topic of annual meetings. In 2011, I held a special session of the annual meeting of the JASL and edited a volume of the journal entitled New Fields of Legal Profession and Sociology of Law.Footnote 2

In Japan, in addition to fully qualified legal professionals, or bengoshi (attorneys at law),Footnote 3 there are many different certified law-related practitioners (quasi-lawyers) such as shihō shoshi (judicial scriveners),Footnote 4 gyōsei shoshi (administrative scriveners),Footnote 5 zeirishi (certified public tax attorneys),Footnote 6 benrishi (patent attorneys),Footnote 7 and shakai hoken rōmushi (labour and social-security attorneys (abbreviated as sharōshi)),Footnote 8 among others. Various law-related practitioners have arisen to meet the practical need for the support of civil and administrative applications to authorities. Currently, these certified law-related practitioners play important roles, providing practical support not only in matters of civil and administrative law, but also in matters of corporate compliance in the specialized law-related fields of business, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Japan.

So far, the legal- and law-related-service market has been shared by bengoshi and various certified law-related practitioners in specialized fields. Bengoshi are regarded as court advocates and representatives in dispute cases, but other law-related practitioners are also regarded as important actors in the practice of civil, administrative, and corporate law. It is worth noting that, while the number of bengoshi is now almost 40,000, the total number of legal and law-related practitioners, including shihō shoshi, gyōsei shoshi, zeirishi, benrishi, and sharōshi, amounts to more than 200,000.

Until about three decades ago, bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners enjoyed a symbiotic relationship, with relatively low competition in the legal- and law-related-services market. However, it seems that this symbiotic relationship began to break up, mainly because of the increasing numbers of bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners, and because of the development of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which deplete the supply of routine legal and law-related work. This paper introduces the current condition of competition in the legal- and law-related-services market in Japan and shows the possible direction of competition in the future.

2. BACKGROUND OF THE TRANSFORMATION

2.1 Conditional Change before the Justice-System Reform in Japan

Until the late 1980s, the legal- and law-related-services market in Japan was relatively stable, because the population of bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners was relatively small. At that time, the need for legal and law-related services was divided clearly based on the specialized fields of practitioners. Bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners shared the market for legal and law-related services symbiotically, without competition. However, that began to gradually change in the 1990s.

One of the most significant background factors in the change was Japan’s entrance into the dynamic global trade market. Especially since the Plaza Accord in 1985,Footnote 9 Japan’s relatively stable domestic industrial market was driven to change by global commercial bodies, investors, nonprofit pressure groups, and non-governmental organizations, which were highly demanding and insistent. Since then, Japanese corporations have become more cautious towards the downside risks of business activities such as a lack of social responsibility, a decrease in product quality, and corporate misconduct, which all damage corporate brand values. Corporations that sustain damage to their public reputations by such problems are generally forced out of the global market and go bankrupt. Critical views on business activities from the global stakeholders mentioned above are highly stringent against corporate misconduct. Thus, Japanese corporations have become more oriented toward risk prevention. Affected by this conditional change, the legal- and law-related-services market has become larger and more diversified.

2.2 Justice-System Reform in Japan and Its Results

The Justice System Reform Council (JSRC), which discussed comprehensive reform of the justice system in Japan, was established under the Cabinet of Japan on 27 July 1999. The JSRC discussed the measurements of enhancement of the use of the civil justice system, expansion of access to justice, promotion of alternative dispute resolution, popular participation in criminal justice, and the expansion of the legal profession, among other issues. On 12 June 2001, the JSRC released its recommendations: (1) the legal population should be substantially increased; (2) training for potential lawyers should be comprehensively reformed; (3) lawyers should be encouraged to focus on social responsibility (public-interest lawyering) and specializations such as business law and international transactions; and (4) the status of people engaged in corporate legal affairs, who have not been admitted to practise, should be reviewed.Footnote 10 Based on the recommendations, the new Law School System (Hōka-Daigakuin) was introduced in 2004, and the traditional judicial examination was replaced by a new examination. Following this reform, the number of successful judicial examinations has risen to about 1,500–2,000 every year, and the total number of lawyers has increased rapidly.

2.2.1 The Increasing Numbers of Bengoshi

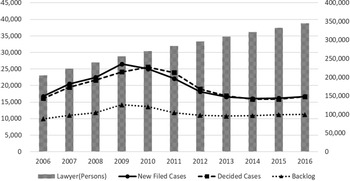

The rapid increase in the number of bengoshi is shown in Figure 1. The total number of bengoshi has been increasing gradually since the 1960s, but the rate jumped drastically beginning around 2000. As of 1 September 2018, there were 39,983 lawyers in Japan.Footnote 11

Figure 1. The number of bengoshi (attorneys) in Japan. Source: Japan Federation of Bar Associations (2017).

This increase has pressured bengoshi to diversify and expand their field of practice. Traditionally, bengoshi were regarded as professionals who only dealt with court-related practices like court representation, filing civil lawsuits, criminal defence, and supporting negotiation, conciliation, and settlement. Recently, however, bengoshi practices have become increasingly business-oriented, as the rate of corporate practice has been increasing. Even though the main part of bengoshi’s frequent legal work is still court-related practices, corporate-related work has also become an important part of their practices.Footnote 12

The number of in-house bengoshi is also increasing to meet the expanding need for legal professionals internal to corporations. In 2002, there were only 80 in-house bengoshi in Japan; by 2017, there were more than 1,900.Footnote 13 In-house bengoshi deal with various corporate legal matters, from drafting contracts, conducting legal research, performing legal management, and organizing negotiations to outreach to outside bengoshi offices. The main focus of in-house bengoshi is preventive legal management, but they also play an important role in proactive corporate strategy. They are regarded as attractors of the transformation of the image of the legal professional in corporations.Footnote 14

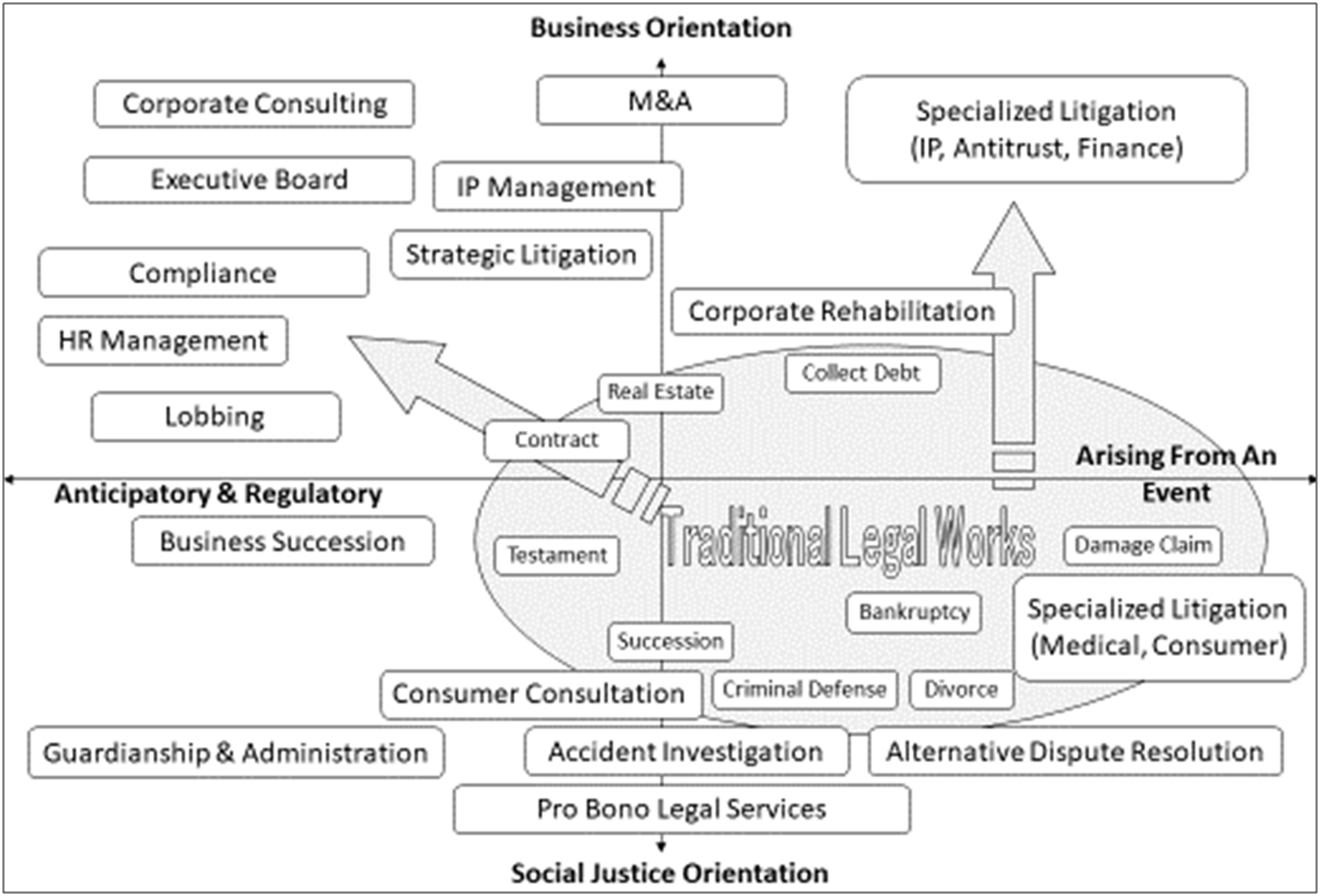

As described, bengoshi’s field of practice has greatly diversified over the recent decades (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Recent diversification among bengoshi in Japan. Source: Fukui & Fukui (Reference Fukui and Fukui2010).

2.2.2 The Slump in Court Practice

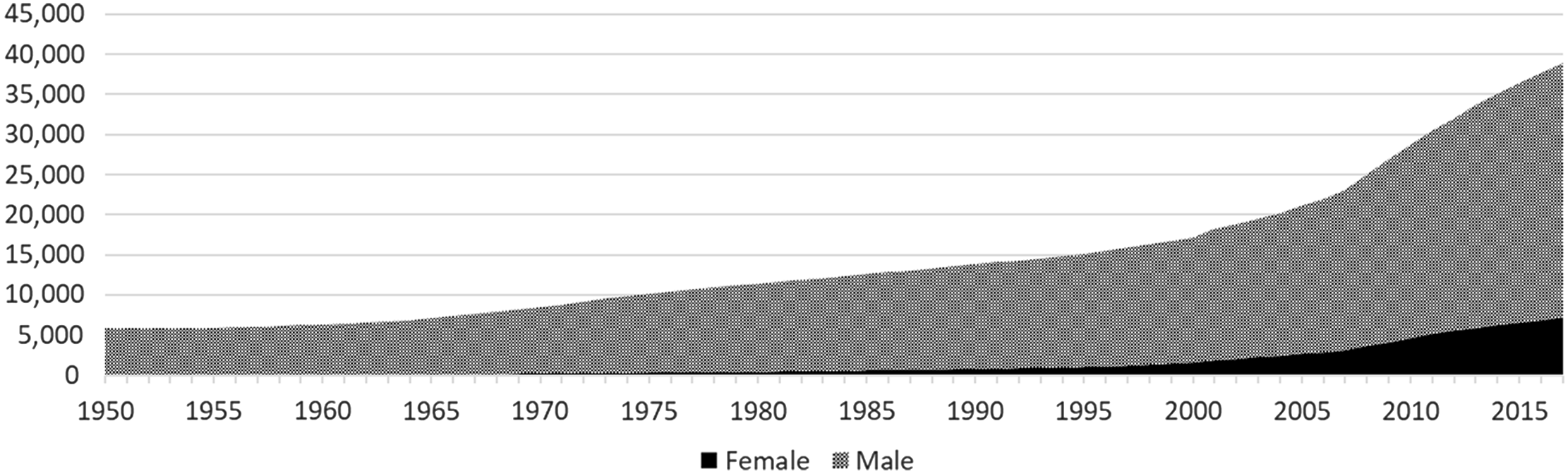

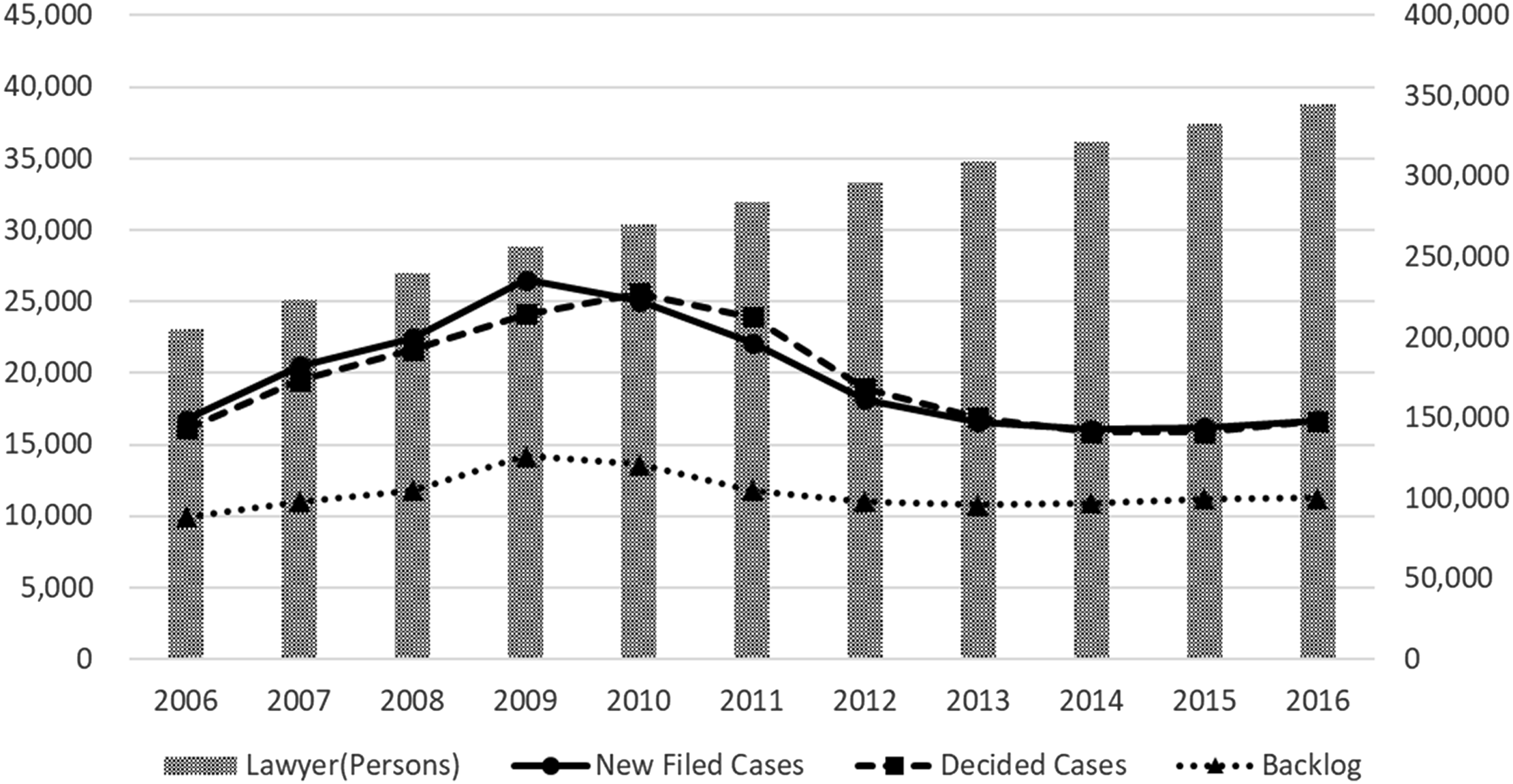

Despite the diversification of bengoshi’s practice in the legal market, the expansion of the number of bengoshi has not been the primary cause of increases in the amount of their court work. Figure 3 depicts a ten-year comparison of the number of bengoshi and transition trends in the number of newly filed cases at local courts.

Figure 3. The number of filed cases of the district court (first instance) and the number of bengoshi, 2006–16. Source: Japan Federation of Bar Associations (2017).

Since 2010, the number of newly filed cases in the district courts in Japan has decreased, even though the population of bengoshi has been increasing. One reason for the decreasing number of cases filed in district courts is the reduction in cases concerning claims for overpayment of credit-loan interest, which was decided in 2006 by the Supreme Court to be unlawful.Footnote 15 That being said, there seem to be more complicated factors behind this decrease.Footnote 16

Faced with a decreasing number of court cases, bengoshi have been transforming their practice, supplementing or even replacing their court-oriented work with more work from the business sector.

3. DEVELOPMENT OF CERTIFIED LAW-RELATED PRACTITIONERS IN JAPAN

3.1 Current Conditions of Practice for Certified Law-Related Practitioners

Like the bengoshi, certified law-related practitioners are also growing in number, and they have an interest in the bengoshi’s service market. As discussed above, the legal- and law-related-services market was formerly symbiotically shared by the bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners. Shihō shoshi dealt with real-estate and commercial registration, judicial documentation, and the procurement of submissions to the judicial authorities.Footnote 17 Gyōsei shoshi dealt with administrative documentation and the procurement of submissions to the administrative authorities.Footnote 18 Zeirishi dealt with documentation for tax-return filing and the procuration of petition for tax complaints.Footnote 19 Benrishi dealt with applications for patents and the procurement of petitions for patent complaints.Footnote 20 Sharōshi dealt with labour and social-security insurance documentation.Footnote 21 Still, there are some other law-related practitioners in Japan.Footnote 22 Their respective roles in the legal- and law-related-services market was not harmonized until the late 1980s.

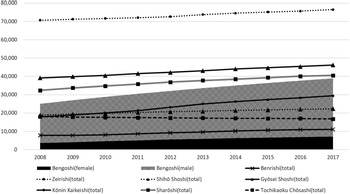

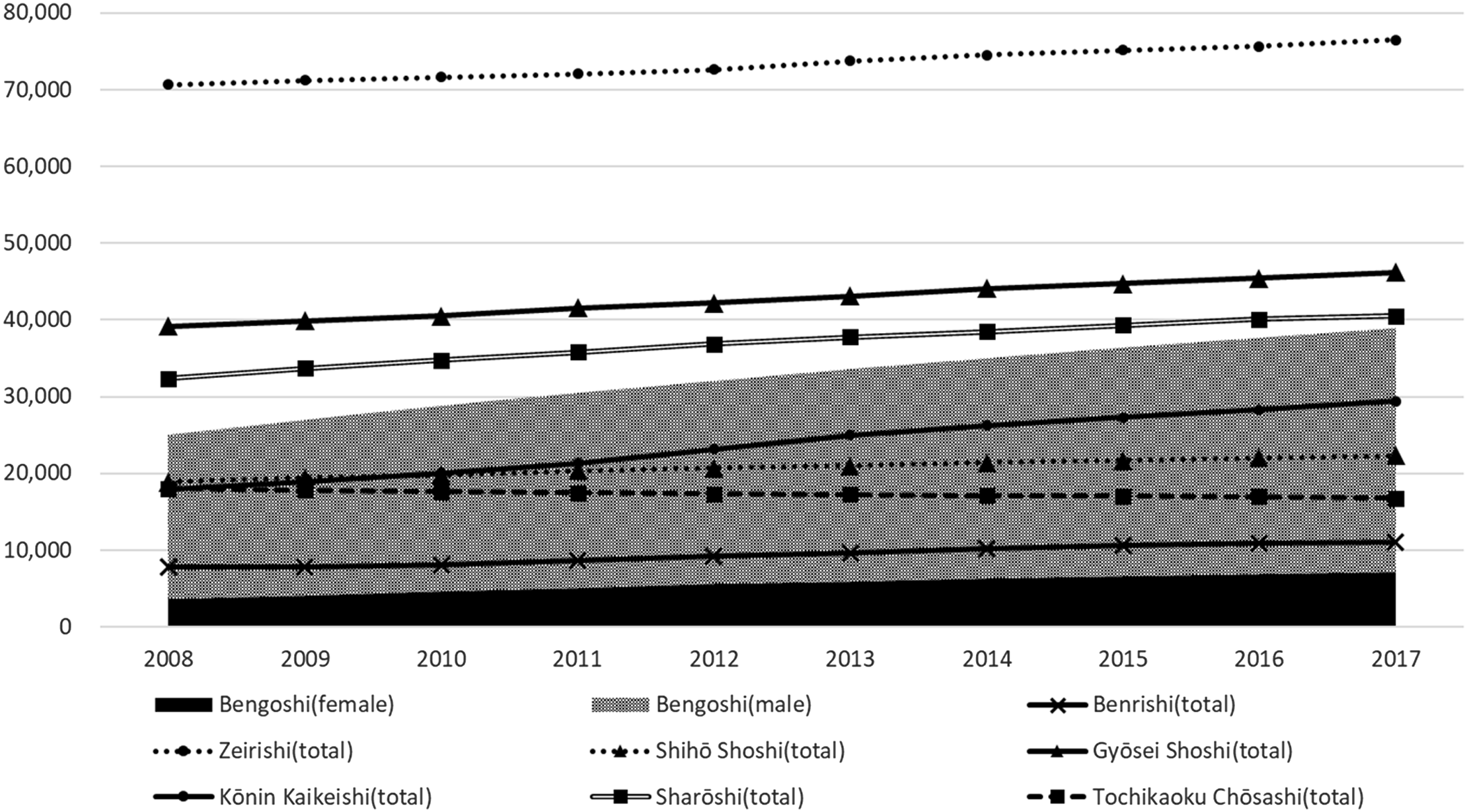

The population of certified law-related practitioners has been increasing. For example, the number of shihō shoshi in 2000 was about 17,000 but, as of April 2018, it had risen to 22,488.Footnote 23 As of 2017, the number of gyōsei shoshi stood at 46,205, of zeirishi at 76,493, of benrishi at 11,057, and of sharōshi at 40,535.Footnote 24 In 2018, their total population was over 200,000 and still increasing (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The transition of the population of law-related practitioners. Source: Japan Federation of Bar Associations (2017).

Another aspect of the transforming conditions of the market for law-related practitioners’ services is the development of ICT and AI. Recently, the Japanese government has been enhancing the comprehensive introduction of ICT for the administrative application of registrations and petitions, which directly relate to the exclusive practical field of gyōsei shoshi.Footnote 25 This has made it much more convenient for applicants to deal with administrative applications by themselves. Tax-return filing, which is an exclusive practical field of zeirishi, is also gradually being replaced by online filing,Footnote 26 because it is convenient for individuals and corporations to enter their revenue directly to report to the tax office. Real-estate and commercial registration, which is an exclusive field of practice of shihō shoshi, is also gradually being replaced by online registration,Footnote 27 though it is still mainly done at the Regional Legal Affairs Bureau. Patent filing, which is an exclusive field of practice of benrishi, has mostly been replaced by online filing.Footnote 28 Additionally, social-insurance filing, which is an exclusive field of practice of sharōshi, has been materially replaced by online filing administered by the Japan Pension Service.Footnote 29

In addition to ICT technology, the development of AI has also led to great changes in the respective fields of practice of certified law-related practitioners. The documentation work dealt with by such law-related practitioners is expected to be replaced by AI documentation assistant systems installed in personal computers and/or connections to the Internet.Footnote 30 Tax preparation and social-insurance applications, regarded as among the most “computerizable” tasks, have traditionally been the exclusive fields of practice of zeirishi and sharōshi, respectively. Legal and administrative documentation, traditionally handled by shihō shoshi and gyōsei shoshi, respectively, are also regarded as “computerizable.” Patent research work, the essential base of patent filing, can be dealt with by AI systems connected to the Internet. As shown above, the current daily work of certified law-related practitioners is threatened by the development of computer- and Internet-based AI systems. Under the pressure of both the increasing professional population and developments in ICT and AI, law-related practitioners are increasingly cultivating new practices beyond their traditional practical fields.

3.2 Developing Fields of Certified Law-Related Practitioners

As discussed above, under the pressure of the increasing professional population and ICT and AI development, certified law-related practitioners are opening up new fields of practice. One of the pioneering examples is that, since 2002, shihō shoshi have been authorized to act with the power of representation at summary courts.Footnote 31 Shihō shoshi can now represent parties at the summary court, in cases under the limit of JPY 1,400,000 (ca. USD 12,000), provided they have received the additional qualification from the Ministry of Justice. Since this amendment, which is limited to civil cases at the summary court, shihō shoshi have gained the same authorization powers as bengoshi.

Another example of a new field of certified law-related practitioners is alternative dispute resolution (ADR). In discussions by the JSRC in the early 2000s, empowerment of ADR was one of the most important issues. The JSRC recommended that efforts to reinforce and vitalize ADR should be made to ensure that people would consider ADR to be an equally attractive option to adjudication.Footnote 32 In response, the certification of ADR-service providers was introduced in 2007 in the form of the Act on Promotion of Use of Alternative Dispute Resolution.Footnote 33 Following this reform, most certified law-related practitioners started to establish their own specialized ADR-service providers, certified by the Ministry of Justice of Japan.Footnote 34 Though its authorization is limited to the specialized fields of practice, from the point of view of certified law-related practitioners’ daily practices, permission to represent clients in dispute resolutions looks attractive.Footnote 35 More than 150 ADR-service providers have been established since 2007.

Corporate consulting is also a remarkable example of a new field for certified law-related practitioners. As mentioned above, since the latter half of the 1980s, Japanese corporate society has become strongly influenced by global stakeholders, who are stringent against corporate misconduct. Japanese corporations have become increasingly protective against downside risks, which can seriously damage their brand value. Affected by this conditional change, certified law-related practitioners are entering the market of corporate consulting in matters relating to their certified field of law. They can give advice relating to their own certified practices, as needed for preventive management of a corporation, and they are gaining respect in such fields.

3.3 Example of the Competition between Bengoshi and Sharōshi

Under such conditions, competition between bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners has become more intense. One example is that between bengoshi and sharōshi. Sharōshi’s main field of practice has traditionally been limited to labour and social-security documentation and the procurement of filings. However, affected by the new needs of sophisticated labour management, sharōshi now get more chances to give advice to SMEs on employment regulations, industrial injury insurance, industrial health and safety management, and similar issues. This change widens sharōshi’s practical field greatly, and they are now regarded as a kind of labour law and social-security-management consultants.Footnote 36

Additionally, sharōshi have been authorized to represent parties at the individual labour dispute-resolution system at the Prefectural Labour Bureaus (since 2003), at the Labour Relation Commission (since 2007), and at their certified ADR-service provider (since 2007).Footnote 37 Also, in 2015, sharōshi gained authorization to be assistant representatives at the court in labour and social-security disputes (for all these, additional certification is required).Footnote 38 Sharōshi’s practices have become similar to bengoshi’s practices in the areas of labour and social-security law, which has led to sharōshi becoming important in the area of corporate compliance in the field of labour and social-security law.Footnote 39

Compared to other certified law-related practitioners, like sharōshi, it is difficult for bengoshi to get consultant positions at SMEs because SME business owners regard bengoshi only as court advocates, and they have very little such corresponding work. They also think that bengoshi’s fees are too expensive in proportion to the work provided.Footnote 40 For some important law-related practices, like making employment regulations for corporations, a task in which sharōshi and bengoshi both are competent, most SME business owners prefer to deal with sharōshi. So, sharōshi and bengoshi get into competition. Another new law-related field of practice in which sharōshi are more dominant than bengoshi is mental health labour-conditions management.Footnote 41

As shown above, in some important corporate-law-related practical fields, bengoshi and sharōshi are in competition, and sharōshi dominate in some fields.

3.4 Other Anecdotal Evidence of the Competition between Bengoshi and Certified Law-Related Practitioners

There is more anecdotal evidence. One such example is the registration practice at the registry office. The registration practice was generally regarded as shihō shoshi’s exclusive field of practiceFootnote 42 ; bengoshi and shihō shoshi had been in conflict on the registration practice because bengoshi sometimes conduct real-estate and/or commercial registration at the registry office on behalf of their clients. Since the case of Bengoshi v. Saitama Shihō Shoshi Association on the matter of bengoshi’s Authorization of Registration Practice,Footnote 43 the registration practice has been officially recognized as being included in bengoshi’s competent practices. According to the decision, Article 3(1) of the Bengoshi Act, which defines bengoshi’s duties in general, their duties cover all legal practices, and these are not excluded by any other acts, like the Shihō Shoshi Act. Even though bengoshi are guaranteed the right to practise registration at the registry office, they are still not always given priority in this field of practice. Most people still regard registration at the registry office as shihō shoshi’s exclusive practice, and they usually commission shihō shoshi to register their real estate and/or to establish a corporation.

Another piece of evidence is the giving of consultation on amicable divorces. Article 763 of the Japanese Civil Code allows a husband and wife to divorce by agreement, in an amicable manner.Footnote 44 Thus, some gyōsei shoshi give advice for profit to a husband and wife, who want to divorce by such an agreement, about achieving a smooth and low-cost divorce with no trouble, because gyōsei shoshi believe that Article 72(1) of the Bengoshi Act, which prohibits the provision of legal services by non-bengoshi, exceptionally permits gyōsei shoshi to do so, since making a notification of divorce to the municipal office on behalf of their clients is included in gyōsei shoshi’s certified scope of practice.Footnote 45 The Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) regards this as illegal but, so far, there has been no decisive precedent on this issue by the court,Footnote 46 meaning that it is still in the grey zone of what is legally permitted. However, even though bengoshi are obviously competent to deal with divorce matters, they seem unable to dominate in this service market.

3.5 Tentative Result of the Discussion

So far, there have not been much detailed empirical data on the competition between bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners. But, as confirmed above, the developing fields of certified law-related practitioners are overlapping with the bengoshi’s areas of practice. Inevitably, in some fields of practice, the competition between bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners has been observed. However, as the population of bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners is increasing, and ICT and AI developments are rapidly progressing, full-scale competition between them seems unavoidable in the near future.

The most competitive areas of practice are presumed to be legal consulting, corporate compliance, and dispute resolution. Most of the certified law-related practitioners have entered into these service markets and began to compete with bengoshi. Even now, bengoshi do not always dominate the competition in these fields, and the competition map of these fields could change greatly in the near future.

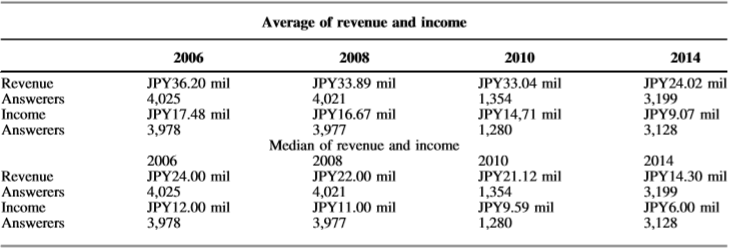

There is only indirect evidence that the annual income (average and median value) of bengoshi is decreasing (Table 1). This decrease seems to correlate with their competition in the service market, even though it can be thought of both as a cause and as a result of their competition.

Table 1. The average and median revenue and income of bengoshi, 2006–14

Source: Japan Federation of Bar Associations (2015).

4. CONCLUSION

Bengoshi and certified law-related practitioners still seem to enjoy a relationship that is mostly symbiotic, sharing the legal- and law-related-services market, but competition among them is increasing, and full-scale competition will be unavoidable in the near future. The number of bengoshi and other certified law-related practitioners is still increasing, and the development of ICT and AI will not stop; both place heavy pressures on the legal- and law-related-services market, fuelling the above-discussed transformation. The main overlapping practical fields, such as legal consulting, corporate compliance, and dispute resolution, are becoming battlegrounds.

From the point of view of the desirable future of the legal and law-related practices, quality competition is welcome, but price competition might cause harmful side effects on the quality of the practices, overall. In the current situation, quality control of legal and law-related practice is essential.

Discussion in this paper still remains provisional analysis, as it is based on past surveys and somewhat dated official statistics. It is necessary to conduct a new survey that properly focuses on this issue to enable a more detailed empirical exploration.