Introduction

This review covers recent archaeological work on Early Iron Age (EIA) to Classical Crete, building upon previous reviews by Matthew Haysom published in AR 2012–2013 (Iron Age to Hellenistic Crete) and AR 2013–2014 (prehistoric to Hellenistic Crete) (Haysom Reference Haysom2012–2013; Reference Haysom2013–2014). The literature cited in this paper includes articles from the Archaiologikon Deltion (ADelt) from the past 15 years (including volumes covering 2006 to 2015), the Archaiologiko Ergo Kritis (AEK) (volumes 3 and 4), and the 10th, 11th, and 12th Cretological conferences, as well as a range of monographs and other publications from around 2010 onwards (excluding works previously covered by Haysom). Accordingly, this review focuses on the 2010s, but also includes select references to work published in the late 2000s and the early 2020s. Only a few of the discoveries and the literature cited below have so far made it into Archaeology in Greece Online (AGOnline; where appropriate references to ID numbers are given in the text that follows).

Notwithstanding the economic crisis and its grave impact on archaeology in Greece (Plantzos Reference Plantzos2018), archaeology in Crete has flourished over the past decade. The hefty volumes of AEK 3 and 4 are indicative of the success of this recent enterprise, which dates from 2008. Indeed, AEK has emerged as the preferred journal for the publication of reports of current archaeological work in the region. Conversely, Cretan contributions to the ADelt, especially concerning the east of the island, are in sharp decline for unclear reasons. Only excavations of the Archaeological Service at Chania and American fieldwork projects at Kommos and in east Crete have received systematic annual reports in the ADelt in the last 15 years, which means that Azoria is the only systematic excavation from EIA to Classical Crete that one can follow uninterruptedly in the ADelt. The new and diversified state of the field leaves a lot to slip through the cracks, with important (and systematic) work potentially not being reported, being reported only in the mass media (and only rarely through press releases from the Ministry), or receiving only interpretative studies which appear long after the actual fieldwork and can be highly selective. A more consistent approach to the reporting of archaeological fieldwork would probably be more useful, and this issue deserves the attention of stakeholders of Cretan archaeology, perhaps in a future AEK meeting.

Reference works and current debates

Literature on EIA to Classical Crete has applied different names to the island’s culture of this period, including Post-Minoan, Dorian, and Greek, but none of them is without conceptual problems and they have grown unpopular as a result. The entry for ‘Ancient Crete’ in Oxford Bibliographies provides an up-to-date literature review (Chaniotis and Kotsonas Reference Chaniotis and Kotsonas2020), while reference works by Saro Wallace (Reference Wallace2010) and Brice Erickson (Reference Erickson2010a) have synthesized data and current interpretations on EIA to Classical Crete. These two works capitalized on monographs of the 2000s, which offered comprehensive studies of the settlements, sanctuaries and cemeteries of the island from the periods in question (Sporn Reference Sporn2002; Prent Reference Prent2005; Sjögren Reference Sjögren2006; Eaby Reference Eaby2007). Major studies of sub-regions of the island, especially the Messara (Lefèvre-Novaro Reference Lefèvre-Novaro2014) and the Mirabello (Gaignerot-Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2016), have also appeared in recent years. Site-specific studies have proliferated, as explained below, and a database for Cretan sites of the 10th to seventh centuries BC is available through the project The Social Archaeology of Early Iron Age and Early Archaic Greece (http://aristeia.ha.uth.gr/theproject.php). A steady flow of collective volumes presents new research and synthesizes earlier work on EIA to Archaic Crete (Rizza Reference Rizza2011; Niemeier, Pilz and Kaiser Reference Niemeier, Pilz and Kaiser2013; Gaignerot-Driessen and Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen and Driessen2014), and one such volume problematizes the low archaeological visibility of the island’s material culture in the Archaic and Classical periods (Pilz and Seelentag Reference Pilz and Seelentag2014). Other books cover specialized topics, such as terracotta plaques and figurines (Pilz Reference Pilz2011; Pautasso and Pilz Reference Pautasso and Pilz2015) or fortifications (Coutsinas Reference Coutsinas2013). Gagarin and Perlman (Reference Gagarin and Perlman2016) provide an authoritative analysis of the Archaic and Classical inscriptions of Crete, which are also explored by the Cretan Institutional Inscriptions project (https://ilc4clarin.ilc.cnr.it/cretaninscriptions/en/). Oikonomaki (Reference Oikonomaki2010) studies the epichoric alphabets of Archaic and Classical Crete. The field is increasingly attracting historiographic studies that situate the exploration of ancient Crete in the context of broader political and disciplinary history (e.g. Whitley Reference Whitley, Haggis and Antonaccio2015b; Kotsonas 2016; Reference Kotsonas2019a). These studies help illuminate the complex pedigree of some of the current debates on the island’s history and archaeology.

Notwithstanding this output, and the fieldwork and research reported below, the archaeology and history of Crete of the first millennium BC remains relatively marginal to the grand narratives of Greek history and archaeology of this period. This attitude has a long history, indicative of which is Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (Reference von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff1893: 24–25) conceptualizing Crete as an isolated island occupied by semi-barbarous people, which was discovered by scholars in Athens only in the fourth century BC. Although current literature does not embrace such terminology, general works on Greek history and archaeology make little reference to EIA to Classical Crete, and, when they do, this is typically limited to Late Minoan (LM) IIIC Karphi and the EIA cemeteries of Knossos (an exception is Hall Reference Hall2014: 190–99 on the Cretan Archaic Gap), while discussion of Greek religion often engages with evidence from the sanctuary of Syme Viannou. Conversely, neither the spectacular finds from the cemetery of Eleutherna nor the systematic fieldwork at the settlement of Azoria, which is probably the best excavated Archaic site anywhere in the Greek world, have been incorporated into the grand narratives of ancient Greece. Perhaps it is too early for this fieldwork to reach broader audiences and perhaps the lack of final publication has a limiting effect. It might also be because Crete is too peculiar for most archaeologists and historians of Greece to engage with and Greek archaeology of the period remains terribly Athenocentric and resists groundbreaking discoveries from alleged peripheries that call for major revisions in the traditional master narratives. Nevertheless, the archaeology of Crete receives greater attention in a recent discourse on the importance of context in Classical archaeology (Osborne Reference Osborne2015; Whitley Reference Whitley2017b; Haggis Reference Haggis2018), which is indicative of the ways in which fieldwork on the island can revolutionize the discipline.

The relative marginalization of the archaeology of Crete is partly due to the problematic concept of Cretan exceptionalism. This concept is centred on perceived unusual attributes of the culture of ancient Crete, which include the remarkably strong religious continuity from the Bronze Age, the limited evidence for pictorial art and the culture of the symposion, the lack of any peripteral temples, the rarity of sculpture and the scarcity of evidence for private inscriptions (e.g. Whitley Reference Whitley, Fisher and van Wees2015a; Reference Whitley and Nevett2017a; Reference Whitley, Parker and Steele2021). The notion of Cretan exceptionalism has received considerable pushback in recent years. Studies on Cretan religion (Haysom Reference Haysom, Haysom and Wallensten2011), the relevance of Homer to Crete (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2018b; Reference Kotsonas2019b), myth in Cretan art (Sporn Reference Sporn2013; Pilz Reference Pilz, Pilz and Seelentag2014; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2019b) and Cretan epigraphic habits (Perlman Reference Perlman, Pilz and Seelentag2014) have challenged the otherness of the island’s culture, while acknowledging remarkable local traditions.

The notion of Cretan exceptionalism has partly been shaped by the island’s close contact with the Eastern Mediterranean in the EIA. Indeed, the study of Near Eastern imports to Crete during this period has become a topic of perennial interest. Recent work on this includes a comprehensive analysis of the island’s record of Near Eastern imports dating to the EIA (Pappalardo Reference Pappalardo2012) and a study focused on Cypriot imports and imitations (Karageorghis et al. Reference Karageorghis, Kanta, Stampolidis and Sakellarakis2014). These catalogue-based projects make important contributions, while adhering to a line of inquiry that has been explored intensively since the 1990s. Contextual analyses of such imports can probably offer more original insights (e.g. Antoniadis Reference Antoniadis2017). The traditional emphasis on imports has offered implicit support to widespread assumptions on the passive role of Cretans in Mediterranean interaction during the EIA. These assumptions seem problematic to me (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Morgan and Charalambidou2017), and they are called into question by the identification of Cretan vases beyond the Aegean, including Late Geometric–Protoarchaic and – much more numerous – Classical pieces in the Eastern Mediterranean (see respectively Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas and Iacovou2012, 156–57; Gilboa et al. Reference Gilboa, Shalev, Lehmann, Mommsen, Erickson, Nodarou and Ben-Shlomo2017) and Protoarchaic pieces at Megara Hyblaia (de Barbarin Reference de Barbarin, Stampolidis and Giannopoulou2020). More exceptional is the discovery of much earlier, Cretan Subminoan-Early Protogeometric pottery in two chamber tombs at Lindos, Rhodes, which show Cretan architectural features and have been attributed to Cretans (Zervaki Reference Zervaki and Polychronakou-Sgouritsa2019). These little known, but highly important, finds can generate a more balanced appreciation of the role of Cretans in Mediterranean interaction during the period in question.

Archaeologists and historians of Crete have been particularly concerned with the poor archaeological visibility of the sixth century BC, which has been variously conceptualized as a ‘Dark Age’, a ‘period of silence’ or the time of the ‘Archaic gap’ (Erickson Reference Erickson2010a: 1–22). The problem has a long history, which has been traced back to the work of Thomas Dunbabin in the late 1930s (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2020: 31–32), and has received considerable attention in the last two decades (e.g. Pilz and Seelentag Reference Pilz and Seelentag2014), during which our understanding of ceramic typology and chronology has improved considerably (Erickson Reference Erickson2010a; Reference Erickson2010b) and the systematic excavations at Azoria in east Crete have revealed a well-preserved Archaic settlement (Haggis Reference Haggis, Gaignerot-Driessen and Driessen2014; Reference Haggis, Haggis and Antonaccio2015; Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry, Snyder and West2011a; Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011b; Haggis and Fitzsimons Reference Haggis and Fitzsimons2020). However, much more groundwork is needed to generate a solid understanding of the material culture of sixth-, and partly fifth-, century BC Crete.

Presently, Classical archaeologists of Crete focus their attention on identifying the andreion, the important all-male political, social and economic institution (Whitley Reference Whitley, Duplouy and Brock2018). The first attempts to identify an excavated building as an andreion can be traced back to the work of Minos Kalokairinos at Knossos (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2016: 320), but over time, and especially during the last few decades, various other buildings in the central and the eastern part of the island have been identified tentatively as andreia (as the following review indicates), with most scholars remaining unconvinced. The frantic search for the andreion parallels the search for Minoan palaces by prehistorians of Crete. However, unlike the numerous Minoan palaces discovered to date, the Cretan andreion remains elusive. Inadequately described by ancient textual sources, and systematically sought after since the beginnings of Cretan archaeology, the andreion has become a holy grail for Classical archaeologists working on the island.

Fieldwork and publication

The discussion proceeds geographically from west to east and chronologically from the LM IIIC to the Classical period, but excludes material dated broadly to the fourth century BC (which may thus be Early Hellenistic).

Chania district (Map 6.1)

Archaeology in the Chania district is dominated by the work of the Greek Archaeological Service. Katerina Tzanakaki (Reference Tzanakaki2016) has produced a comprehensive thesis on the site of Chania (Kydonia) from the Geometric to the Classical period. In addition to a discussion of local geology, and a gazetteer of locations of domestic, cultic, industrial, and burial activity, the work offers a diachronic analysis of occupation at the site. Archaeological evidence from the period after the abandonment of the LM IIIC settlement on Kastelli hill is very poor. Protogeometric evidence is scarce and comes from only two locations in the periphery of the modern city: in the mid-eighth century, occupation resumed on top of the prehistoric ruins on Kastelli hill and another settlement nucleus emerged at a short distance to the southwest of the hill. Despite a destruction event in the early seventh century BC, the two nuclei persisted and have yielded fragments of stone architecture and sculpture dating from the Archaic period. References by Herodotus (3.44.1, 3.59.3–14) to settlement at the site by people from Zakynthos, to their expulsion by settlers from Samos in 524 BC and to the involvement of Aeginetans in the expulsion of the Samians in 519 BC have not been confirmed by the material record. The city grew considerably in the Classical period, and its main cemetery was located southeast of the settlement.

Map 6.1. Map showing sites in west and central-west Crete mentioned in the text: 1) Phalasarna; 2) Fournakia; 3) Kato Kefala; 4) Elyros; 5) Lissos; 6) Nerospilia; 7) Chania; 8) Tarrha; 9) Aptera; 10) Kalyves; 11) Kera; 12) Agia Eirini; 13) Onithe Gouledianon; 14) Stavromenos; 15) Thronos/Kephala; 16) Kalogeros; 17) Melidoni Cave; 18) Eleutherna; 19) Orne Kastellos; 20) Axos; 21) Idaean Cave. © BSA.

Tzanakaki’s thesis builds upon an overview of the history of occupation at Chania produced by Maria Andreadaki-Vlazaki (Reference Andreadaki-Vlazaki, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011a: esp. 121–27, 136 and 140–41) (Fig. 6.1 ). This allows for better contextualization of discoveries made at Chania in recent years, including within the LM IIIC settlement (ID2832, ID2833; Tsigkou Reference Kataki and Tsigkou2008: 1159; Reference Tsigkou2010; Andreadaki-Vlazaki Reference Andreadaki-Vlazaki2010 (ID9408, ID9409, ID9410, ID9411); Reference Andreadaki-Vlazaki2011b (ID9106)), the Geometric to Classical settlement (Preve Reference Preve2006; Reference Preve2008; Andreadaki-Vlazaki Reference Andreadaki-Vlazaki2010 (ID9408, ID9409, ID9410, ID9411); Reference Andreadaki-Vlazaki2011b (ID9106); 2022; Tsigkou Reference Tsigkou2015; for a room filled with imported transport amphorae of Classical date, see Tsigkou 2010: 1692; Reference Tsigkou2015: 82–83; Kataki and Tsingou Reference Kataki, Tsigkou and Gavrilaki2018) and burials of LM IIIC (Protopapadaki Reference Protopapadaki2015), Late Geometric II (Kataki and Tsigkou Reference Kataki and Tsigkou2012: 741) and Classical date (Kataki Reference Kataki2009: 910; Kataki and Tsigkou Reference Kataki and Tsigkou2011 (ID9107); 2012: 741; Preve Reference Preve2012; Reference Preve2015; Skordou Reference Skordou2012). The notable finds on the plot of 1 Katre Street, on the Kastelli hill, include a sanctuary of the late seventh and early sixth century BC and evidence for a major seismic event of the early sixth century BC (Andreadaki-Vlazaki Reference Andreadaki-Vlazaki2022: 31–32).

6.1. Plan of modern Chania showing the location of settlement and burial remains from the EIA to the Roman period (10th century BC to 4th century AD). The Kastelli hill overlooks the harbour area. © M. Andreadaki-Vlazaki.

The name a-pa-ta-wa is attested on a Linear B tablet from Knossos, but prehistoric (specifically LM II-IIIB) habitation in the area of Aptera is located north of the Classical city, on the hill of Palaiokastro (Papadopoulou Reference Papadopoulou, Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018). The hilltop of Aptera has yielded evidence for occupation going back to ca. 700 BC, but individual burials located west and east of the hill date to ca. 1000 BC (Niniou-Kindeli and Tzanakaki Reference Niniou-Kindeli, Tzanakaki, Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018). Archaic and Classical occupation is represented by sporadic finds, a small temple with a double cella, which dates to the fifth century BC and overlies an earlier cult site, and evidence for the construction of the fortification wall before the mid-fourth century BC. Burial activity at the western cemetery commenced in the LM IIIC-late or the Subminoan period, but can be traced more clearly from the late eighth century BC, when pithos burials became common (Tzanakaki Reference Tzanakaki2007; Reference Tzanakaki, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011a; Niniou-Kindeli and Tzanakaki Reference Niniou-Kindeli, Tzanakaki, Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018). Pithos burials persisted to ca. 400 BC, but at least one secondary cremation is documented, and rock-cut pits seem to have been introduced at the end of the sixth century BC. Part of the cemetery was levelled during the Late Archaic period, with old burials giving way to new ones. This development involved some ritual activity, which is represented by a deposit of the first half of the fifth century BC containing pottery and silver pins probably deriving from disturbed burials.

East of Aptera, a building of the seventh and sixth centuries BC was excavated at Kalyves (Tzanakaki Reference Tzanakaki2006), while further east, at Kera, fieldwork revealed 104 pits of the 12th century BC (Fig. 6.2 ), which contained burned soil, animal bone, horn and shell, plant remains, ceramics, lumps of clay, and stone tools (Milidakis Reference Milidakis2015; Papadopoulou Reference Papadopoulou, Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018: 33; Milidakis and Papadopoulou Reference Milidakis and Papadopoulou2020). Comparable finds are known from the district of Rethymnon, at Agia Eirini and Eleutherna (on which see below), as well as Chamalevri and Thronos/Kephala (Sybrita).

6.2. Kalyves Apokoronou, Kera pit 62. © Ministry of Culture and Sports/Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania.

Other activity at the north coast and its vicinity includes: the discovery of a marble head from a large funerary monument at Phalasarna, dated ca. 370–350 BC (Fragkakis Reference Fragkakis2016–2017); the exploration of the cave sanctuary of Nerospilia, southwest of Chania, which hosted the cult of Eileithyia from the fourth century BC onwards (Liakopoulos Reference Liakopoulos2020: 674–75); and the offering to the local Ephorate of a number of Attic white-ground and especially black-figure lekythoi of the second quarter of the fifth century BC from Kato Kefala (south of Kolymvari), a site that falls into the district of ancient Pergamos and is known from limited and scattered excavations of Classical graves (Kataki Reference Kataki2012; Reference Kataki2020).

The rest of the district of Chania from the EIA to Classical period is little known. Contributions from recent years include: the publication of a cluster of seven seventh/sixth-century BC pithos burials from Tarrha (Tzanakaki Reference Tzanakaki2013); a study of the topography and the little known archaeological record of Elyros, which includes a few Classical burials (Kyriazopoulou Reference Kyriazopoulou, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011); the identification of a fifth- or early fourth-century BC building at the sanctuary of Asklepios at Lissos (Kanellopoulos Reference Kanellopoulos2020: 756); a cache of 58 well-preserved vases, and a few clay figurines and sherds of Late Geometric to Classical date, offered by a villager who claimed they came from Fournakia, northwest of Palaiochora (Tzanakaki Reference Tzanakaki2011b).

Rethymnon district (Map 6.1)

Recent archaeological output in the region of Rethymnon includes richly illustrated accounts of finds from Eleutherna and the Idaean Cave.

Map 6.2. Map showing sites in central Crete mentioned in the text: 22) Phaistos; 23) Kommos; 24) Kouroupitos Cave; 25) Gortyn; 26) Agia Pelagia; 27) Kavrochori; 28) Krousonas; 29) Prinias: Dodeka Apostoli; 30) Prinias: Siderospilia; 31) Prinias: Patela; 32) Kophinas; 33) Phoinikia; 34) Heraklion; 35) Knossos: Tekke; 36) Knossos; 37) Aitania; 38) Astritsi: Kephala; 39) Choumeri: Kephala; 40) Arkalochori; 41) Rotasi; 42) Kefala; 43) Smari; 44) Kastelli; 45) Lyktos; 46) Afrati; 47) Inatos; 48) Hersonissos; 49) Malia: Pezoula; 50) Agios Konstantinos; 51) Katofygi-Erganos; 52) Syme Viannou. © BSA.

Besides newspaper reports on discoveries from recent years (ID271, ID1827, ID2005, ID2857), the archaeology of Eleutherna, and especially of the cemetery of Orthi Petra, is showcased in a recent exhibition catalogue, a popularizing book, and a conference volume, which cover familiar ground but also present new material. A notable new find presented in the catalogue is a Late Archaic inscription from the eastern part of the city (Stampolidis Reference Stampolidis, Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018: 121 and 184, no. 67). The importance of this location emerged through the study of the notebooks of Federico Halbherr, which resulted in the discovery of an earlier Archaic inscription (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas and Gavrilaki2018a). The popularizing book presents the collection of the newly established museum of Eleutherna (see below), including a fair amount of previously unknown finds (Stampolidis Reference Stampolidis2020a). The conference volume includes short studies on a range of finds from the cemetery of Orthi Petra (Stampolidis and Giannopoulou Reference Stampolidis and Giannopoulou2020).

More comprehensive work on the cemetery of Orthi Petra includes a monograph that publishes some 400 clay vessels from chamber tomb A1K1 that date from the ninth to early sixth centuries BC (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2008), and an unpublished PhD thesis that deals with over 150 pieces of gold, silver and electrum jewellery from the site (Mitaki Reference Mitaki2019). Shorter studies review the archaeology of the cemetery (Stampolidis Reference Stampolidis2020b) and discuss the form and modern reconstruction of two seventh-century BC monuments (Stampolidis and Koutsogiannis Reference Stampolidis and Koutsogiannis2013) and a range of pieces of Protoarchaic limestone sculpture (Stampolidis Reference Stampolidis2014). The archaeology of other locations at Eleutherna has also received considerable attention. The top of the acropolis (Pyrgi) yielded LM IIIC-PG pits – comparable to those found at Chamalevri, Thronos/Kephala (Sybrita), Agia Eirene (on which more below) and Kera (as noted above) – as well as a temple (an oikos with a porch), which was built in the Protoarchaic period and remained in use for many centuries (Kalpaxis et al. Reference Kalpaxis, Tsigonaki, Spanou and Bitis2021). The finds from the temple include a Daedalic mould-made figurine and a bronze mitra (a helmet belly guard) with a Daedalic face (Spanou Reference Spanou2020; Kalpaxis et al. Reference Kalpaxis, Tsigonaki, Spanou and Bitis2021: 164–65) (Fig. 6.3 ). Other studies discuss finds from the top of the Nisi hill, which extends immediately west of the acropolis of Eleutherna. These finds include numerous clay figurines of various types that date from throughout the EIA (Karamaliki Reference Karamaliki2020), as well as evidence for occupation and the making of ceramics during the Late Geometric and Protoarchaic periods (Tsatsaki Reference Tsatsaki2013).

6.3. Bronze mitra with Daedalic face. © Eleutherna, Sector II excavations.

Recent publications on the Idaean Cave include a popularizing well-illustrated book, which outlines the exploration of the site and its finds (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki2011), as well as a set of three volumes that summarize the results of specialist studies on a range of artefact classes (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki2013). The first of these three volumes covers the textual tradition on the Idaean Cave, the landscape of the Nida plain and the history of excavations in the cave. It also offers an outline of activity at the site from the Neolithic to Roman period and a study of ritual practices. The second volume discusses the clay finds (vessels, other equipment and figurines), the bronzes (vessels, other equipment, figurines, jewellery, weapons and other finds; on bronze figurines see also Lagogianni-Georgakarakou Reference Lagogianni-Georgakarakou, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011), the gold and silver objects, the ivory and bone objects, and a range of other finds made in faience (on which see also Psaroudakis Reference Psaroudakis2012–2013) (Fig. 6.4 ), glass, rock crystal, amber, and stone, as well as the inscriptions. The third volume includes photographs and drawings of numerous finds, some previously unknown to the scholarly community.

6.4. Figurine of male god made of Egyptian blue. After Psaroudakis Reference Psaroudakis2012–2013: 94–95 no. A2. © K. Psaroudakis. Photo by Y. Papadakis-Ploumidis.

Axos has recently received renewed attention, which has shed light on the ancient topography (Tegou Reference Kataki2013; Reference Tegou, Gaignerot-Driessen and Driessen2014). Locations of interest include the Subminoan to Hellenistic sanctuary of Aphrodite, the Archaic to Roman suburban sanctuary of Demeter stou Gerakaro, the ‘andreion’ on the acropolis, the LM IIIB to Early Geometric and Archaic to Roman cemetery at Megalos Trafos/Teichio, and the EIA cemetery at Limnostratari.

The extra-urban sanctuary in the Melidoni Cave was probably connected to Axos for part of the EIA to Classical period. Recent studies have discussed a few figurines of Subminoan to Classical date (including fragments of life size terracotta statues of the first half of the sixth century BC), and they have shown that a female divinity was worshipped at the site in this period (Pateraki Reference Pateraki2016–2017; Gavrilaki Reference Gavrilaki2017: 217–26).

Thronos/Kephala (Sybrita) has yielded a clay pictorial krater that dates to the 10th century BC and depicts two male warriors dancing next to a lyre and perhaps more instruments, indicating the importance of dance in the Cretan socio-political system (D’Agata Reference D’Agata2012). The village of Kalogeros, just east of Thronos/Kephala, is the findspot of some 600 figurines of Subminoan to Hellenistic date (Karamaliki Reference Karamaliki, Mitsotaki and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2019). South of Thronos and close to the south coast of Crete lies Orne Kastellos, a fortified acropolis inhabited in the earlier part of LM IIIC (Kanta Reference Kanta, Papadakis and Pelantakis2014; Kanta et al. Reference Kanta, Stampolidis, Tzigounaki, Stefanakis, Stampolidis and Giannopoulou2020).

Other fieldwork was conducted in the broad area surrounding the city of Rethymnon. New fieldwork at Onithe Gouledianon revisited the Archaic and later settlement and the general topography of the site (Psaroudakis Reference Psaroudakis2015). A Classical cemetery was excavated at Stavromenos, east of Rethymon (Tzigounaki Reference Tzigounaki2020: 115). The settlement of Agia Eirini, 3km southeast of Rethymnon, yielded LM IIIC remains underlying a Hellenistic settlement (Karamaliki Reference Karamaliki2015). These remains include traces of buildings as well as two pits cut into bedrock and filled with burned soil, cooking and table ware, and animal bone. The contents of the pits are ascribed to ritual meals and are comparable to finds made at nearby Chamalevri, and also at Thronos/Kephala (Sybrita), Eleutherna and Kera (on the last two sites, see above).

Notwithstanding the importance of these scholarly outputs, the western half of Crete suffers from the paucity of any major final publication of material from the period in question since 2008. This has perpetuated the imbalance of archaeological research between the west and east part of the island.

Heraklion district (Map 6.2)

A review of the archaeology of Knossos from the end of the Bronze Age through the EIA (Hatzaki and Kotsonas Reference Hatzaki, Kotsonas, Lemos and Kotsonas2020) and the Knossos Urban Landscape Project (KULP) (Fig. 6.5 ) have shed new light on the site. KULP confirms that Knossos greatly reduced in size by the LM IIIC period. The potential extent of ca. 20ha, however, would make the site the largest in Postpalatial Crete (Cutler and Whitelaw Reference Cutler, Whitelaw, Mitsotaki and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2019: 17–19). Knossos grew markedly in the EIA to reach 50–60ha in the eighth and seventh centuries BC (i.e. four times larger than previously assumed). This was a nucleated settlement surrounded by cemeteries, but involved no dispersed villages, which refutes the model of polis formation through synoecism at Knossos (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Mitsotaki and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2019c; cf. Kotsonas et al. Reference Kotsonas, Whitelaw, Vasilakis, Bredaki and Gavrilaki2018). Although sixth-century BC Crete is poorly documented, especially in relation to Knossos (but see Paizi Reference Paizi2019), the KULP material includes pieces that clearly date to this period (Fig. 6.6 ). Additionally, the Early Classical city seems to match Geometric and Protoarchaic Knossos in size, and indicates stability over the sixth century BC, with notable growth during the Classical period (Trainor Reference Trainor, Mitsotaki and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2019: 4–5).

6.5. Knossos: KULP survey plans showing the distribution of pottery in different phases, from the LM IIIB/IIIC to the Hellenistic period, as well as the outline of the settlement in these phases. Created by Todd Whitelaw. © BSA.

6.6. Knossos: KULP survey plan showing the distribution of EIA, Archaic, and Archaic-Hellenistic pottery, as well as the location of EIA tombs in the Knossos valley. Created by Todd Whitelaw. © BSA.

The work of the Archaeological Service at Knossos and Heraklion has produced further insights. The Anetaki plot at Knossos yielded two kilns of the LM IIIC period and two more of the Protogeometric period (Sythiakaki Reference Sythiakaki2020: 28), as well as pits and other deposits with burned remains and EIA material (Kanta Reference Kanta, Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018: 263). A destroyed Archaic funerary monument was identified at Knossos Tekke (Mavraki-Balanou Reference Mavraki-Balanou2008a). Previously unpublished EIA finds from burials located north of Knossos appeared in a recent exhibition (Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas Reference Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018: 288–303). Further north, in the southern suburbs of Heraklion, rescue work explored a rock-cut chamber tomb and a pit grave of the EIA (Spercheiou street) (Sythiakaki Reference Sythiakaki2020: 32) and a larnax of the Protogeometric period (Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 66). At Heraklion itself, two limestone pieces of seventh-century BC architectural sculpture from a door frame were found reused in a Venetian structure located north of the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (Ariadnis street) (Sythiakaki Reference Sythiakaki2020: 36–37; cf. Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas Reference Stampolidis, Lourentzatou and Fappas2018: 307). The lintel illustrates a row of bovids, while the vertical jamb shows a goddess wearing a polos. The pieces are attributed to a sanctuary located on the acropolis of ancient Heraklion.

West of Knossos, an EIA chamber tomb from Phoinikia was published (Galanaki and Papadaki Reference Galanaki, Papadaki, Loukos, Xifaras and Pateraki2009), and two others were found at Kavrochori (ID1817; Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 67). Further west, Late Archaic and Classical burials were identified among Hellenistic graves at Agia Pelagia (ancient Apollonia) (Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 67; Kontopodi et al. Reference Kontopodi, Thanos, Papadaki, Sidiropoulos and Galanaki2020: 136).

East of Knossos, at Aitania, pottery from two EIA chamber tombs excavated in the 1950s and the 1990s was published (Galanaki and Papadaki Reference Galanaki and Papadaki2019), while an Archaic to Hellenistic sanctuary was tentatively identified on the hilltop of Kefala, south of Gournes (Panagiotakis, Panagiotaki and Dipla Reference Panagiotakis, Panagiotaki, Dipla and Gavrilaki2011; Panagiotakis and Panagiotaki Reference Panagiotakis and Panagiotaki2014–2015). This may have been a border area between Knossos and Lyktos. Further east, Malia Pezoula, a defensible but not inaccessible site that lies southwest of prehistoric Malia, commands a view of the north coast of Crete and dates from the 11th and 10th centuries BC (Mandalaki Reference Mandalaki2006). The site comprises a stand-alone building complex, which preserves evidence for two architectural phases. Because of its very small size (0.04ha), Malia Pezoula could be classified as a farmstead, in which case it would be the first of its kind in Crete to be fully excavated, and a rare find for the Aegean of the period as a whole. Around Hersonissos, finds from the period in question include Geometric material from north of the Amirandes Hotel (Mandalaki Reference Mandalaki2010: 1657; ID8580) and at Lyttos Beach Hotel (Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 61), and Archaic and Classical material from Limenas Hersonissou (Mandalaki Reference Mandalaki2010: 1657; ID8581).

Fieldwork activity extended over different parts of the plain of Pediada. The recent publication of the Galatas survey, which covers diachronic occupation in the northwest part of the area, established that, from the EIA to the Classical period, habitation was restricted to Astritsi Kephala and Choumeri Kephala (Watrous et al. Reference Watrous, Buell, Kokinou, Soupios, Sarris, Beckmann, Rethemiotakis, Turner, Gallimore and Hammond2017). The settlement pattern of the Pediada changed markedly in the LM IIIC period, when the Minoan town of Kastelli was abandoned and other sites (re)-emerged, namely Smari and Lyktos. The fortified Prepalatial acropolis of Smari was re-inhabited ca. 1200 BC, when three megara were built on the hilltop; habitation spread beyond the old fortifications and involved a new rampart (Chatzi-Vallianou Reference Chatzi-Vallianou2016). After a destructive episode in the LM IIIC or Subminoan period, only the hilltop was resettled and the three megara were re-inhabited, allegedly by a ruler and his kin, and remained in use until the late seventh century BC, when the site was abandoned. A temple dedicated to Athena, which yielded ample terracotta plaques, is also assigned to the late eighth and seventh centuries BC. The excavator, Chatzi-Vallianou, identifies Smari with Homer’s Lyktos, and interprets the site in light of Homeric and other textual tradition for Lyktos (thus, the megara are thought to have been used both for Homeric type feasting and for the Lyktian syssitia, the common meals shared by citizens). She further suggests that the ancient toponym was relocated to the area of Classical to Roman Lyktos (on the hill of Xidas) after the abandonment of Smari. I have previously expressed scepticism over the identification of Smari with early Lyktos, the associated use of Homer and the actual date of the latest material from Smari, which seem to be as late as the fourth century BC (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2018b: 6–7; Reference Kotsonas2019a: 433–34).

Limited LM IIIC surface evidence from the top of the Xidas hill indicates that Lyktos was perhaps founded at this time (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2019a: 410 and 431–33). The excavations, which commenced in 2021, revealed Protogeometric material and thick deposits of Archaic and Classical date, which include ample pottery imported from Athens (Fig. 6.7 ), and considerably fewer pieces from Laconia and Corinth. The range of material found in these deposits may not represent ordinary settlement debris.

6.7. Attic black-figure and red-figure pottery of the sixth and fifth centuries BC from Lyktos, Sector A. © Lyktos Archaeological Project and Archaeological Society at Athens.

Two clusters of Archaic settlement remains were excavated at Agios Konstantinos, northeast of Lyktos and just west of Avdou (Mavraki-Balanou et al. Reference Mavraki-Balanou, Kastanakis, Triantafyllidi, Papadaki and Gavrilaki2011: 96–97; Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 54). The settlement was destroyed by fire ca. 550 BC.

Finds from Lyktos, Smari, and other sites confirm that the Pediada was a major production area of relief pithoi. Numerous pieces of Archaic style have been found in Hellenistic settlement contexts around this area and elsewhere in Crete, thus raising questions on the survival of individual vessels over several centuries and the persistence of earlier styles into later periods (Galanaki, Papadaki and Christakis Reference Galanaki, Papadaki, Christakis, Haggis and Antonaccio2015: 326–28; Galanaki et al. Reference Galanaki, Papadaki, Sidiropoulos, Spyridakis and Moutzouris2017a: 205–07; Galanaki, Papadaki and Christakis Reference Galanaki, Papadaki and Christakis2019; Ximeri Reference Ximeri2021: 194–218). Particularly interesting is a Late Archaic to Early Classical pithos from Arkalochori, which bears pictorial decoration and two graffiti (Galanaki et al. Reference Galanaki, Papadaki, Simantoni-Bournia, Kritzas, Rogdakis and Sinodinaki2017b) (Fig. 6.8 ).

6.8. Late Archaic–Early Classical relief pithos from Arkalochori. © K. Galanaki. Photo by Y. Papadakis-Ploumidis.

The area west of the Pediada is dominated by work on Prinias. Indeed, the Italian team working at the site has produced probably the highest number of excavation reports and interpretative studies for any Cretan site in recent years. Their work is reported on an annual basis in the Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente (ASAtene) (see, e.g. Pautasso et al. Reference Pautasso, Rizza, Pappalardo, Hein, Biondi, Gigli Patanè, Perna and Guarnera2021), but there are also ample reports in the tenth, 11th, and 12th Cretological conferences, in AEK 4 and in Stampolidis and Giannopoulou (Reference Stampolidis and Giannopoulou2020). This research output is summarized by Pautasso (Reference Pautasso2014) and Palermo (Reference Palermo and Gavrilaki2018). Below, I comment on the most recent and important studies.

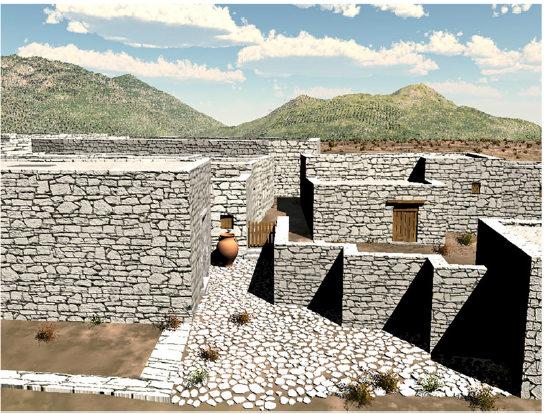

Recent fieldwork on the hill of Prinias Patela has targeted the settlement area south of Temple B, which has yielded late eighth- and seventh-century BC structures (Gigli Patanè Reference Gigli Patanè and Gavrilaki2018; Pautasso et al. Reference Pautasso, Rizza, Pappalardo, Hein, Biondi, Gigli Patanè, Perna and Guarnera2021), and the building complex on the south-central part of the Patela hill, which was built in the mid-seventh century to host both communal and domestic functions (Fig. 6.9 ) and overlies possible ritual remains of the two previous centuries (Rizza and Pautasso Reference Rizza and Pautasso2015; Pautasso and Rizza Reference Pautasso, Rizza, Lefèvre-Novaro, Martzolff and Ghilardi2015). Likewise, the area of Temple A was found to have attracted ritual activity from as early as the 12th century BC (Pautasso and Rizza Reference Pautasso, Rizza and Gavrilaki2018). The rich sculptural decoration of Temple A was re-examined in light of recent findings. Accordingly, the famous frieze of the riders is now reconstructed as a dado frieze on the façade of the temple. Also, the relief of a female figure on the lintel is reconsidered in light of the discovery of a new fragment, while the discovery of the squatting body of an animal corresponds to a wing fragment found in earlier excavations, and the two indicate that the temple was adorned with two sphinxes. The sculptural decoration of Prinias Temple A has previously been compared to Neo-Hittite reliefs and Egyptian monuments, but a recent study draws closer comparison with the EIA temple of ‘Ain Dārā; in North Syria (Yalçin Reference Yalçin2020), a monument that was destroyed by airstrikes during the Turkish invasion of Syria in 2018. Another site of EIA cult activity at Prinias Patela is indicated by the discovery of terracotta figurines and sculptural finds in the area of the Hellenistic fortress (Biondi Reference Biondi2020).

6.9. Prinias Patela: virtual reconstruction of Courtyard AZ and Building C from the south. 3D reconstruction by S. Rizza. © Archive of the Italian Archaeological Mission at Prinias.

Finds from the excavations of 1969–78 at the EIA necropolis of Prinias Siderospilia are reported in numerous papers in AEK 4, in Stampolidis and Giannopoulou (Reference Stampolidis and Giannopoulou2020) and in the 12th Cretological conference. This literature covers the development of the cemetery, the human bones from inhumations, the pottery, the bronze vessels, the jewellery, and the evidence for contact between the site and the Aegean and Near East. In anticipation of the forthcoming final publication of the cemetery, I single out a diachronic analysis of human activity at Siderospilia and of the typology of the tombs (Rizza Reference Rizza, Mitsotaki and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2019) and the study of several huge, pedestalled kraters with figural decoration from the eighth century BC (Pautasso Reference Pautasso2018). Two dozen pieces of EIA pottery from the site, including one of the kraters in question, were explored by means of chemical analysis, which shed light on local production and identified Attic imports (Pautasso et al. Reference Pautasso, Rizza, Pappalardo, Hein, Biondi, Gigli Patanè, Perna and Guarnera2021: 30–52). A burial enclosure with an enchytrismos and several inurned cremations of the EIA was discovered at Dodeka Apostoli, 250m north of Prinias Siderospilia (Biondi Reference Biondi, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011), while one or more burial areas and other locations of EIA activity were identified around Prinias by a recent surface survey (Biondi Reference Biondi, Lefèvre-Novaro, Martzolff and Ghilardi2015a).

Varied archaeological activity was conducted in the area of Krousonas. Archaic houses overlying LM IIIC layers were excavated on the hill of Koupos-Kastellas, while a LM IIIC tholos tomb was found in the broader area (Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 56). Lastly, a new prehistoric and Classical cave sanctuary identified in the Kouroupitos Cave yielded material from different periods, including LM IIIC-Protogeometric pottery and figurines (Darlas Reference Darlas2020: 162; Efstathiou, Kanta and Kontopodi Reference Efstathiou, Kanta and Kontopodi2020: 64–65, fig. 5).

The archaeology of the Messara and the rest of south-central Crete has been treated in a comprehensive synthesis encompassing the Late Bronze Age and the EIA (Lefèvre-Novaro Reference Lefèvre-Novaro2014; also Santaniello Reference Santaniello, Lefèvre Novaro, Martzolff and Ghilardi2015a). Italian fieldwork at Gortyn and Phaistos is reported on an annual basis in ASAtene, but here emphasis is placed on other publications on material from these sites.

A new monograph provides a comprehensive synthesis of the archaeology of Gortyn from the EIA to the Classical period (Anzalone Reference Anzalone2015a; see also Santaniello Reference Santaniello2013). Recent fieldwork has focused on the EIA settlement on the south slope of the Profitis Ilias hill (ID1807, ID1915; Allegro Reference Allegro, Lefèvre-Novaro, Martzolff and Ghilardi2015; Allegro, Anzalone and Santaniello Reference Allegro, Anzalone, Santaniello and Gavrilaki2018; Allegro and Anzalone Reference Allegro and Anzalone2020). Traces of activity go back to the 12th century BC, and the site developed into a densely built settlement by the late ninth century BC. It was rebuilt following an earthquake, ca. 700 BC. The preserved layout (which comprises five buildings) dates to the seventh century BC, by which time the site covered an area of 15ha. The settlement was abandoned ca. 600 BC and its population moved to the plain as part of the urbanization of Gortyn. The clay figurines from Profitis Ilias date from the main period of the settlement (tenth to seventh centuries BC), but also persist into the Classical and Hellenistic periods, probably because a sanctuary was located in the vicinity (Anzalone Reference Anzalone2015b). Recent studies also treat a potters’ quarter located on the foothills of Profitis Ilias, from ca. 600 BC (Santaniello Reference Santaniello, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011), as well as an EIA to Hellenistic sanctuary on the Armi hill, east of Profitis Ilias, which yielded pottery and clay figurines (Anzalone Reference Anzalone2013). Lastly, new excavations targeted the sanctuary of Apollo Pythios through small trials (Bonetto et al. Reference Bonetto, Bertelli, Brombin, Colla, de Scarpis di Vianino and Metelli2020; Bonetto et al. Reference Bonetto, Bertelli, Brombin, Colla, de Scarpis di Vianino and Metelli2021; see also Bonetto, Bertelli and Colla Reference Bonetto, Bertelli and Colla2015). This work found that cult activity began in the Protogeometric period and dated the first monumental structure to around the mid-seventh century BC. This structure is reconstructed not as a roofed temple, but as an open-air enclosure with stone steps on which inscriptions were incised. The structure was remodelled during the fifth century BC.

In addition to the annual reports in ASAtene, numerous papers, especially in AEK 3, have reported on excavation and surface survey at Phaistos. Novel insights into the period under review are summarized by Longo (Reference Longo, Lefèvre-Novaro, Martzloff and Ghilardi2015a; Reference Longo2015b). They include the identification of a scattered habitation pattern during the EIA (Fig. 6.10 ). A settlement on top of the hill of Christos Efendi with associated burials downhill (on this see also Greco and Betto Reference Greco and Betto2015; Greco, Betto and Giglio Reference Greco, Betto and Giglio2020: 334–36) broadly coexisted with the ‘Geometric Quarter’ in the area of the Minoan palace (on which see Carinci and Militello Reference Carinci and Militello2020) and with EIA burials found northwest and southwest. The scant Protogeometric and Geometric remains from Haghia Photini are hard to interpret (Di Biase Reference Di Biase2020: 379–80 and 383). Surface survey of the underlying plain yielded poor evidence for habitation from the EIA to the Classical period (Santaniello Reference Santaniello2015b), but further settlement and burial areas were identified within a radius of a few kilometres. The Archaic and Classical periods are poorly attested, but a Classical sanctuary may have existed on Christos Efendi, as deduced from an inscription to Athena(?) rendered before firing on a ceramic piece (Greco and Betto Reference Greco and Betto2015: fig. 5; Longo Reference Longo, Lefèvre-Novaro, Martzloff and Ghilardi2015a: 179 pl. VI,4). Archaic architectural materials also come from the area east of Christos Efendi. The fortification walls probably date from the fourth century BC or later, and earlier dates previously proposed cannot be confirmed. Likewise, the ‘Temple of Rhea’ is now dated after the Archaic period (Iannone Reference Iannone2020), although Carinci and Militello (Reference Carinci and Militello2020: 305–06) seem less certain on the dating.

6.10. Plan of Phaistos marking areas of settlement and burial in the Protogeometric and Geometric periods. Settlement areas (insediamento) and burial areas (area funeraria) are marked around the site of the Minoan palace (area del palazzo). © Fausto Longo and Phaistos Project.

Recent publications have revisited EIA pottery from Kommos. This includes an analytical project on the Phoenician transport amphorae (Gilboa, Waiman-Barak and Jones Reference Gilboa, Waiman-Barak and Jones2015) and a new interpretation of a local seventh-century BC cup, which carries the most complex and multifigured scene on any Cretan ceramic vessel to date (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2019b).

Sporadic news comes from the southeastern part of the Heraklion district. After a demise throughout most of the LM II and III period, the Minoan peak sanctuary of Kophinas recovered in LM IIIC and attracted material throughout the EIA (Spiliotopoulou Reference Spiliotopoulou2014: 170; Reference Spiliotopoulou2015: 285–86). The publication of a selection of old finds from the Minoan to Roman cave sanctuary at Inatos (Tsoutsouros) includes an impressive range of EIA terracotta figurines and numerous faience figurines from ca. 600 BC, some of which illustrate scenes of childbirth or kourotrophic figures, suggesting that the divinity worshipped was Eileithyia (Kanta and Davaras Reference Kanta and Davaras2011; Kanta, Davaras and Betancourt Reference Kanta, Davaras and Betancourt2022; the publication of the Egyptian-type artefacts from this site has also just appeared: Hölbl Reference Hölbl2022).

New studies summarize old and new evidence from Rotasi (ancient Rhytion), with emphasis on the discovery of five inurned cremations of the Geometric and Protoarchaic periods, which yielded ceramic and metal finds, as well as an early sixth-century BC inscribed gravestone (ΣTAΣIΟΣ EMI) and two Archaic decorated stelai (Galanaki and Papadaki Reference Galanaki, Papadaki and Gavrilaki2011; Galanaki et al. 2017). Two late seventh–sixth century burials excavated at Afrati Orthi Petra in 1975 were published recently (Biondi Reference Biondi2015b). The earlier burial was an inurned cremation, the later burial was in a clay sarcophagus, and both were found in a poorly explored area southeast of the ancient settlement. Additionally, Katofygi-Erganos, on the western foothills of the Lasithi mountains, yielded a Subminoan pithos burial (Mavraki-Balanou Reference Mavraki-Balanou2008b).

Lastly, several new publications present the archaeology of the sanctuary of Syme Viannou, which now boasts the longest publication series of any Greek archaeological project in the country. One new volume treats the roof tiles, which date from the Early Classical to the Roman period (Zarifis Reference Zarifis2020) (Fig. 6.11 ). This is the first publication of a sizeable body of roof tiles from Crete and is therefore foundational to any future research on this understudied body of material. Another volume treats the clay anthropomorphic figurines, including figures in the round and in relief, and composite votives from the early second millennium BC to the fourth century BC (Lebessi Reference Lebessi2021). This volume (in addition to Lebessi Reference Lebessi2018–2019) demonstrates the leading role of Cretan workshops of terracotta figurines in the introduction of different iconographic types and their dissemination elsewhere in the Greek world. Additionally, two new studies present a list of unpublished metal finds from the sanctuary (Muhly and Muhly Reference Muhly, Muhly, Giumlia-Mair and Lo Schiavo2018: 546; Papasavvas Reference Papasavvas, Papantoniou, Morris and Vionis2019: 247) and report on the results of chemical analysis of bronze figurines from the site (Muhly and Muhly Reference Muhly, Muhly, Giumlia-Mair and Lo Schiavo2018: 548–50).

6.11. Typology of roof tiles from Syme Viannou, including type I (sixth to fifth century BC) and type II (fourth to third centuries BC). The columns show – respectively – different profiles of side wall, drip edge and joining edge (from Zarifis Reference Zarifis2020: 76, fig. 12). © N. Zarifis.

Lasithi district (Map 6.3)

Major final publications of material from east Crete of the period in question focus on LM IIIC sites and assemblages. Indeed, the site of Karphi recently received two monographs: one authoritative study on the pottery from the excavations of 1937–39 (Preston Day Reference Preston Day2011), and one comprehensive analysis of results from the 2008 excavations (ID777; Wallace Reference Wallace2020). This output probably makes Karphi the best published site of EIA Crete. Following suit, the Kavousi publication series has expanded through the addition of a new volume on the LM IIIC hilltop village of Vronda. The volume discusses the architecture, pottery, figurines, stone tools and other objects, and plant remains (Gesell and Preston Day Reference Gesell and Preston Day2016). A publication of comparable scope focuses on the LM IIIC elite House A.2 at Chalasmenos (Eaby Reference Eaby2018). This first volume of the final publication of this site comes only a few years after the end of fieldwork in 2014. A preliminary study also examines a LM III kiln found at Chalasmenos (Rupp and Tsipopoulou Reference Rupp and Tsipopoulou2015).

Map 6.3. Map showing sites in central-east and east Crete mentioned in the text: 53) Karphi; 54) Anavlochos; 55) Dreros; 56) Priniatikos Pyrgos; 57) Meseleroi; 58) Mochlos; 59) Azoria; 60) Kavousi Vronda; 61) Chalasmenos; 62) Praisos; 63) Droggari of Ziros; 64) Roussa Ekklesia: 65) Itanos; 66) Cavo Plako. © BSA.

The region of the Mirabello, from Anavlochos to Kavousi, which has been the focus of an impressive range of excavation and survey projects in the last decades, received a comprehensive study by Florence Gaignerot-Driessen, the excavator of Anavlochos (Gaignerot-Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2016). The study is especially concerned with settlement development, urbanization and the rise of the polis, and includes a catalogue of sites dating from the Postpalatial to the Archaic period.

The ridge of Anavlochos controls the Mirabello valley, and thus the route that connects central and east Crete (ID772, ID2769, ID4548, ID5433, ID6195, ID6890, ID8499, ID8615; Zographaki Reference Zographaki2005; Reference Zographaki2006; Zographaki, Gaignerot-Driessen and Devolder Reference Zographaki, Gaignerot-Driessen and Devolder2012–2013; Gaignerot-Driessen et al. Reference Gaignerot-Driessen, Fadin, Bardet and Devolder2016; Gaignerot-Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen, Mitsotaki and Tzedaki-Apostolaki2019; Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2020; Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2022) (Fig. 6.12 ). The site was probably established in the transition to the LM IIIC period, when it was organized in hamlets. Anavlochos underwent a process of nucleation starting in the Protogeometric period. The houses were arranged in terraces and extended over 10ha by ca. 700 BC, shortly after which the settlement was abandoned. An extensive burial area with graves dating from the 12th to the seventh centuries BC lies at the north foot of the hill. The most impressive burial monument is a tumulus with a diameter of 15m, which was used in the eighth and seventh centuries BC. Lastly, three deposits of votive material, which date between the LM IIIC and the Classical period, were excavated at Kako Plai, half-way between the settlement and the cemetery (Gaignerot-Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2022).

6.12. Plan of Anavlochos. © Anavlochos Project/L. Fadin, F. Gaignerot-Driessen, B. Guillaume.

New fieldwork at Dreros was missed in previous overviews of EIA to Classical Crete but deserves considerable attention (ID1371, ID1957, ID4081, ID8504, ID8505; Zographaki and Farnoux Reference Zographaki and Farnoux2010; Reference Zographaki and Farnoux2011; Reference Zographaki and Farnoux2012–2013; Reference Zographaki and Farnoux2014a; Reference Zographaki, Farnoux, Gaignerot-Driessen and Driessen2014b; Farnoux, Kyriakidis and Zographaki Reference Farnoux, Kyriakidis and Zographaki2012; Farnoux and Zographaki Reference Farnoux, Zographaki and Gavrilaki2018). This fieldwork explored different periods of the ancient city, revealing its notable extent in the Hellenistic period. Concerning earlier periods, the fieldwork established that the structure excavated by Xanthoudidis on the west acropolis of the site was a temple (Temple A) (Figs 6.13–6.14 ), as the excavator had assumed, rather than an andreion, as others have proposed. Cult activity in the area must have been open-air in the early eighth century BC, at roughly the time the more famous Temple B was erected in the area of the agora. A ritual deposit, which was found below a paved area inside Temple A, was rich in kalathoi and wheel-made figurines dating from the early eighth century BC to the mid- and perhaps the late seventh century BC. Temple A was probably erected in the course of the seventh century BC. The temple remained in use until ca. 200 BC, when Dreros was destroyed by Lyktos. The new fieldwork also established that the architecture in the area of the agora is not Archaic, but Hellenistic in date, which does not exclude the earlier use of the same space for civic functions. Remarkably, an Archaic inscription, which mentions a tomb, was found in the area of the agora (Zographaki and Farnoux Reference Zographaki and Farnoux2014a: 786, fig. 3).

6.13. Dreros, the temple of the west acropolis. © A. Farnoux/EFA.

6.14. Dreros, plan of the temple of the west acropolis. © S. Zugmeyer/EFA.

The Azoria project, which completed its second five-year plan in 2013–17, is exploring a hilltop settlement of the poorly understood Archaic period (ID765, ID1700, ID2856, ID4550, ID5576) (Fig. 6.15 ). Annual reports in the ADelt (2006–2015) are too numerous to cite, but longer reports appear in Hesperia (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry, Snyder and West2011a; Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011b) and there are also ample interpretative studies (e.g. Haggis 2014; Reference Haggis, Haggis and Antonaccio2015; Haggis and Fitzsimons Reference Haggis and Fitzsimons2020). This literature explains how the site was transformed from one of several small EIA villages around Kavousi to an urban settlement of 15ha in the late seventh century BC, when it was radically rebuilt with megalithic, roughly concentric terrace walls, which physically supported the hillsides and notionally tied the community together. The labour and resources invested in creating domestic and communal spaces increased drastically, and new kinds of communal architecture were introduced at this time. This is evidenced especially by the Monumental Civic Building, which is a single large hall with a permanent seating arrangement for assemblies and feasting, and the Communal Dining Building, which is internally differentiated into separate dining rooms serviced by kitchens and storage rooms. The houses around the hilltop are much larger than the Cretan houses of the EIA, and they show notable elaboration and clearly differentiated functional spaces. Judging by their form, their contents, and their relationship to public space, these houses must have been inhabited by elite groups, which maintained privileged access to the community’s wealth and power. The systematic archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological research, which is conducted on a scale and intensity that is probably unmatched for Aegean sites of the historical period, have established that the urban centre of Azoria was mainly a consumption zone, with production and processing taking place in the outskirts of the city and also in outlying farmsteads. The end of fieldwork at Azoria leaves many questions open, concerning, for example, the ancient name and political status of this community (on epigraphic evidence from the site see West Reference West2015), but has already revolutionized our understanding of Archaic Crete and has given the public a sizeable and well-preserved archaeological site, which offers unique insights into ancient society and economy.

6.15. State plan of Azoria south acropolis (2017). © R.D. Fitzsimons/Azoria Project.

Recent work has shed light on Protoarchaic to Classical activity on the island of Mochlos, which is better known for its Minoan antiquities. Apparently, the summit of the island, which was previously unoccupied, attracted building activity during the seventh century BC and also at around 400 BC (Vogeikoff-Brogan Reference Vogeikoff-Brogan, Kephalidou and Tsiaphaki2012). The seventh-century BC architecture, which includes a hearth and the pottery found with it, such as a Corinthian Transitional oinochoe (a rare find for Crete) (Fig. 6.16 ), suggest that people from a nearby community sporadically came to the summit of Mochlos to partake in drinking and feasting activities through which they could have promoted socio-political aspirations.

6.16. Corinthian oinochoe from Mochlos (P 1613). © Mochlos Excavations. Photo by C. Papanikolopoulos.

Praisos has received a synthesis of old and new archaeological data in light of broader questions concerning commensality and citizenship (Whitley Reference Whitley2014). The animal bone assemblage recovered from the dump of the old excavations at the so-called andreion has generated intriguing insights into feasting and the Cretan polis (Whitley Reference Whitley, Duplouy and Brock2018; Whitley and Madgwick Reference Whitley, Madgwick, van den Ejinde, Biok and Strootman2018).

New work on the north necropolis of Itanos has shown that the necropolis was established in the seventh – or perhaps the eighth – century BC. It was arranged in terraces and had a large enclosure; the early burials were in pits and were largely destroyed by later tombs (ID2822, ID5575; Tsingarida and Viviers Reference Tsingarida, Viviers, Lemos and Tsingarida2019) (Fig. 6.17 ). Some 100m north of the necropolis, a cluster of cremation burials from ca. 700 BC yielded, among other finds, a few spaghetti-ware aryballoi (which are otherwise rare on Crete) and a pyxis with a battle scene (Sofianou and Saliaka Reference Sofianou, Saliaka, Kapsomenos, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Andrianakis2011). The seventh-century enclosure was transformed into a new architectural complex of 300m2 in the early sixth century BC, with different rooms dedicated to feasting and storage and involving copious imported drinking vessels. The building was destroyed ca. 500 BC, but was reoccupied in the fifth century only to be abandoned in the mid-fourth, around which time burial activity resumed at the site. Surface survey in the territory of Itanos identified only a few Geometric to Classical sites (D’Agata et al. Reference D’Agata, Duplouy, Moody, Rackham and Gavrilaki2018), the most notable being a small sanctuary of Demeter at Vamies, which yielded the remains of a rectangular building and ample pottery and figurines from the seventh (and perhaps the eighth) century BC to the late Hellenistic period (Siard and Duplouy Reference Siard and Duplouy2014).

6.17. Itanos necropolis: plan of the excavation (2015) of the southern sector (Archaic funerary complex and Hellenistic necropolis). © Archaeological Mission of Itanos/CReA-Patrimoine-Université libre de Bruxelles.

Following his major study of Crete in the Archaic and Classical periods (Erickson Reference Erickson2010a), Brice Erickson has produced several site-specific publications. These concern a large deposit of the Early Classical period from Priniatikos Pyrgos (Istron), the contents of which indicate public feasting (Erickson Reference Erickson2010c), as well as Protoarchaic to Hellenistic finds (mostly pottery and figurines) from the old excavation at the spring sanctuary of Roussa Ekklesia (Erickson Reference Farnoux, Kyriakidis and Zographaki2009; Reference Erickson2010b) (Fig. 6.18 ). It appears that the latter site hosted the cult of a goddess responsible for natural fertility and human growth, as well as a male rite of passage.

6.18. Terracotta plaques from Roussa Ekklesia, seventh and sixth centuries BC. © B. Erickson.

Other archaeological news from the Lasithi district is limited, but includes the following: the identification of LM IIIC occupation on the Cavo Plako promontory near Palaikastro (Sofianou and Thanos Reference Sofianou and Thanos2015); the clandestine excavation of a small tholos tomb of the Subminoan-Protogeometric period at Droggari of Ziros (Sofianou Reference Sofianou2010; ID8574); the excavation and prompt publication of the pithos burial of a ‘male spinner’ from Meseleroi, which dates to the late eighth or early seventh century BC (Apostolakou Reference Apostolakou2007a; Vogeikoff-Brogan and Kirkpatrick Smith Reference Vogeikoff-Brogan and Kirkpatrick Smith2009–2010); the offering to the Archaeological Museum of Agios Nikolaos of clay and bronze vessels and a few other objects of EIA and perhaps other date from Meseleroi (Apostolakou Reference Apostolakou2007b).

Museums

The last decade has been a fascinating period for Cretan museums, irrespective of the economic crisis that has swept across Greece. The reopening of the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion is undeniably the most prominent development. However, the archaeological museum of Sitia has also reopened and that of Agios Nikolaos is being refurbished. New museums opened at Chania, Eleutherna and Gazi (Archaeological Collection of Malevizi), and others will be opening very soon at Rethymnon and the Messara.

The Archaeological Museum of Heraklion has a fabulous display of material dating from the historical period (Rethemiotakis Reference Rethemiotakis2020; cf. Haysom Reference Haysom2013–2014: 85–86). On the upper floor of the museum are rooms dedicated to the island’s settlements, sanctuaries and cemeteries, broadly separating material of the EIA and the Archaic period from the material of the Classical and later periods. The ground floor has a room dedicated to sculpture of the Daedalic, Archaic, and Classical styles. Daedalic art also featured in the exhibition Daedalus: In the Footsteps of the Legendary Craftsman, which focused on Minoan material (Mandalaki Reference Mandalaki2021).

The remarkable collection of the Archaeological Museum of Sitia (on which see Haysom Reference Haysom2013–2014: 86) showcases, among other things, material from the newly discovered cremations at Itanos and a range of Archaic vessels with relief decoration originating from ritual deposits from the area of modern Sitia. The display at the Archaeological Museum of Agios Nikolaos is designed to include a section that covers east Crete from the 10th century BC to the fourth century AD, including settlement development (with emphasis on Kavousi Kastro and Azoria), sanctuaries (at Anavlochos, Sitia, Azoria, Dreros) and burials (from Sitia and Ierapetra) in the region. The treatment of the east Cretan city states (Latos, Olous, Dreros, Istron, and – to a lesser extent – Hierapytna, Praisos, and Itanos) covers the economy, everyday life and religion, and focuses on Hellenistic and later finds (Zografaki and Zervaki Reference Zografaki and Zervaki2020: 243–46).

The concept and structure of the display at the new Archaeological Museum of Chania are discussed in Papadopoulou and Tzanakaki (Reference Papadopoulou and Tzanakaki2013; Reference Papadopoulou and Tzanakaki2015). Concerning the period discussed in this review, the display covers the following: the stories for the foundation of west Cretan cities in the EIA and the legendary figures who held key roles in these stories; the development of major settlements and city states; the archaeology of Kydonia, Aptera, and other west Cretan cities; economy and trade (including the import and imitation of Attic vases and the circulation of coins); households; sanctuaries and cult; death and burial.

An Archaeological Museum and an associated park in Eleutherna was inaugurated in 2016 (Stampolidis 2018: 156–63; Reference Stampolidis2020a). The museum showcases spectacular finds from over three decades of excavations of the University of Crete at the site. Particular attention is given to the finds from the EIA cemetery of Orthi Petra, which are wide-ranging in form and material, and include copious imports from different parts of the Eastern Mediterranean. The branding of the display under the label ‘Homer in Crete’ is unnecessary, since Eleutherna was apparently unknown to Homer and the Homeric tradition. The relevance of Homer to ancient Crete can best be approached in the light of current interpretations of the formation of the epics and the archaeological record (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2018b; Reference Kotsonas2019b).

The Archaeological Collection of Malevizi opened at Gazi in 2011 and includes finds from the prehistoric and Classical periods (Kanta and Serpetsidaki Reference Kanta and Serpetsidaki2015: 54–55). Most of the objects on display come from the former Metaxas collection, but 30 objects are from the area of Gazi.

The scope of the new Museum at Rethymnon ranges from deep prehistory to the foundation of the Greek state in 1830; indeed, this is celebrated as the first fully diachronic museum on Crete (Gavrilaki et al. Reference Gavrilaki, Tegou, Varthalitou and Fiolitaki2015). Concerning the period discussed in this review, the display covers the settlement pattern that emerged at the end of the Bronze Age, and the transition from refuge settlements to cities, including foundation myths, writing, and the introduction of coinage.

The chronological scope of the Archaeological Museum of Messara extends from the prehistoric to the Byzantine period (Sythiakaki Reference Sythiakaki2020: 22–23).

Conclusion

In the past decade, archaeological research in Crete of the EIA to Classical period has flourished in many respects, except for final publications of large bodies of material, which remain uncommon. Excavations continued at the sites of Chania, Eleutherna, Prinias, Gortyn, Phaistos, Azoria and Itanos, and new fieldwork commenced at Anavlochos, Dreros, and most recently Lyktos. Active surface surveys remain limited in comparison to previous decades, but the urban surveys at Knossos and Phaistos are generating important new insights into diachronic occupation at these two major sites. Additionally, as many as eight archaeological museums have recently been opened, reopened, or are about to open. This floruit of Cretan archaeology comes despite the challenges created by the international financial crisis and its harsh impact on Greece, and, more recently, the constraints posed by the global pandemic (including the decline in construction and thus in rescue excavations).

While archaeological research in Crete is thriving, it is often treated as relatively marginal, and – arguably – rather inconsequential to the bigger narratives of Greek history, art, and archaeology. Revising the current paradigm of the study of ancient Greece into one that is more accommodating to regional trajectories is probably the greatest challenge for the archaeology of Greece in the 21st century; the thriving research in Crete can lead the way, as evidenced especially by the emphasis it receives in the recent discourse on the importance of context for Classical archaeology (Osborne Reference Osborne2015; Whitley Reference Whitley2017b; Haggis Reference Haggis2018).