Introduction

2021–2022 has seen the dynamic return of many archaeological projects and the beginning of new ones (Map 3.1 ), thanks to the lifting of the most stringent pandemic travel restrictions, which limited possibilities in the past two years. Collaborative projects taking advantage of new technologies have made important new discoveries, especially in the sphere of underwater archaeology. Overall, studies ranging from surface survey, geoarchaeology, and traditional excavation have brought to light a wealth of new data that brings significant insights to the archaeology of Greece, from prehistoric to modern times. The key archaeological developments of 2021–2022 are summarized below.

Map 3.1. Map showing sites mentioned in the Newsround: 1) Veroia; 2) Anthemous Valley; 3) Ioannina; 4) Skiathas-Kato Polydendri; 5) Preveza; 6) Kastro at Kallithea; 7) Alonissos, Agios Petros; 8) Elateia; 9) Agia Marina; 10) Eleon; 11) Amarynthos; 12) Trapeza; 13) Kotroni; 14) Styra; 15) Gourimadi; 16) Tenea; 17) Ambelakia; 18) Kerameikos; 19) Aegina, Mount Oros; 20) Praso; 21) Koroni; 22) Tolon; 23) Epidauros; 24) Asine; 25) Kalaureia; 26) Fournoi; 27) Kalamata; 28) Kythera, Mentor shipwreck; 29) Antikythera shipwreck; 30) Karydaki; 31) Phaistos; 32) Gortyn; 33) Khavania; 34) Itanos. For the Small Cycladic Islands Project, not shown in this map, see Fig. 3.54. © BSA.

Epirus and Central Macedonia

The Ephorate of Antiquities of Ioannina reports on the 2021 discovery of a Bronze Age settlement (2000–1100 BC), close to the beltway around Ioannina city (ID15057). Among the finds were stone tools as well as handmade, unpainted, and painted fine ware and coarse ware, some of which are decorated. The finds provide valuable information regarding habitation patterns in the liminal areas of the lake basin around Ioannina during the Bronze Age. These finds contribute to improving the otherwise fragmented picture of settlement organization in the interior of Epirus during the late prehistoric period.

Janusz Czebreszuk (Polish Archaeological Institute at Athens), in cooperation with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and the Adam Mickiewicz University of Poznań, reports on the 2021 season of the Anthemous Valley Archaeological Project (ID18174). The project has as its focus the reconstruction of human–environment relations in an alluvial part of the lower basin of the Anthemous Valley (Fig. 3.1 ). The time period of interest is the Early Holocene natural evolution of the landscape and the identification of human interventions during the Neolithic, Bronze, and Early Iron Ages. The methodologies used are geoarchaeological, including vibra-coring, electrical resistivity tomography, and laboratory analysis of sediments for palaeogeographical reconstructions. This project is a continuation of the earlier work that has taken place in the Anthemous Valley since 2010.

3.1. General view of the Anthemous Valley. © Polish Archaeological Institute at Athens (photo: L. Pospieszny).

In 2021 geophysical survey both in Agia Paraskevi and in Vassilika-Metamorfosi showed aggradation deposits that covered the oldest pre-Holocene terrace. The eastern part of the valley, where the Early Bronze Age toumba is located, was also investigated, with the aim of understanding a possible continuity of the settlement from the Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age. A percussive core that was scheduled to be taken at Vassilika-Kyparissi stopped 2m from the surface due to a breakdown of the drilling equipment. The core was split open to assess the damage. Its structure was undisturbed and showed clear anthropogenic sediments with numerous layers of charcoal and several pottery fragments, one of which was dated to the Middle Neolithic period. Continued research in the valley will contribute further to the understanding of the Neolithic and Bronze Age landscape of the Anthemous River Valley.

The Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia reports on the discovery of a marble statue, almost one metre in height, in the centre of ancient (now modern) Veroia (ID17017), very close to the archaeological site of Agios Patapios, in one of the very few unbuilt city blocks (Fig. 3.2 ). The statue dates to the Imperial period, when the city – as the seat of the Koinon of the Macedonians and neokore (sexton) of imperial worship – was the first polis of Macedonia. With a chlamys (cloak) thrown over its left shoulder, which wraps around the left hand, the naked youth stands firmly in contraposto, recalling Classical prototypes, particularly statues of Hermes and Apollo. For some reason, despite the fact that the artist had advanced in his depiction of the frontal surfaces, coming almost to a final stage, he then decided to abandon the process halfway. This phenomenon makes the statue particularly valuable for the study of processes of craftsmanship, as well as of the creation of copies of well-known prototypes.

3.2. Statue uncovered in the rescue excavation at Veroia. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia.

Thessaly and West Greece

Architectural remains of a monumental building were brought to light in 2021 during excavation work led by archaeologist Nektaria Alexiou (Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa) at the site known as Skiathas in the coastal area of Kato Polydendri next to the Agiokampos harbour, and in an area where a marble threshold and parts of walls could be seen (https://digitalculture.gov.gr/2021/11/evrimata-tis-anaskafikis-erevnas-sti-thesi-skiathas-sto-kato-polidendri-larisas/). From the excavation data so far, it appears that this is a sanctuary of Hellenistic times (third-second century BC), made of poros and local stone (Fig. 3.3 ). Part of an architrave and five Doric capitals have been identified among the building remains. Inside the structure, a statue pedestal, part of a column, a marble table leg, and two marble heads of children (one male and one female) came to light (Fig. 3.4 ). The fortified settlement, with which this structure is associated, occupies an area of some 22ha. Only the defence wall had previously been investigated, by Athanasios Tziafalias.

3.3. Hellenistic temple structure at Skiathas, viewed from above. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa.

3.4. Marble statue head of a boy found at Skiathas. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa.

Other finds from the 2021 excavation include clay textile weights, clay lamps, and fragments of commercial amphorae. Significantly, stamped tiles with the names of the owners of ceramic workshops have been identified, as well as a tile with the inscription MEΛIBOIAΣ, which probably identifies the settlement at the Skiathas site with Melivoia, an important ancient city of Magnesia. On a lower terraced level, a square tower was investigated, which belongs mainly to the Byzantine period (Fig. 3.5 ). Further research is expected to provide answers to important archaeological questions with respect to this coastal area and its rich archaeological history.

3.5. Square tower of the Byzantine period. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa.

The Ephorate of Antiquities of Preveza reports that the head of a statue (Fig. 3.6 ) dating to the Roman period was pulled up from the sea off the coast near Preveza (ID15058; https://www.tovima.gr/2021/10/12/culture/preveza-anasyrthike-apo-ti-thalassa-kefali-agalmatos-romaikon-xronon/). It probably dates to the period of Antoninus or Severus (second/third century AD). The head is made of Pentelic marble and is almost intact, apart from parts of the nose, right ear, and chin. The object has been transferred to the Archaeological Museum of Nikopolis to undergo the necessary conservation.

3.6. Roman period head retrieved from the sea near Preveza. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Preveza.

Central Greece

The Central Achaia Phthiotis Survey (CAPS; https://caps.artsrn.ualberta.ca/) is a research project that developed out of the Kastro Kallithea Archaeological Project, which finished its fieldwork in 2013. This innovative landscape project, which had a pilot fieldwork season in 2019 (ID12959) and continued in 2021 (ID18176), is co-directed by Sophia Karapanou (Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa) and Margriet Haagsma (University of Alberta). It is supported by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and the CIG. CAPS seeks ‘to contribute to the re-evaluation and study of so-called “marginal landscapes” in the Mediterranean and focuses on an endangered and topographically challenging region, Achaia Phthiotis, on the margins of the Thessalian plains in Central Greece’ (Haagsma et al. Reference Haagsma, Karapanou, Toufexis, Vouvalides, Vaxevanopoulos, Chykerda, Middleton, Wiznura and Sanchez-Azofeifa2021). The focus of the project is the study of some 3,000ha of cultivated and uncultivated land surrounding the Kastro at Kallithea, dating to the fourth–second century BC (Fig. 3.7 ).

3.7. The CAPS 2021 team, seen here at a distance, surveying the Neolithic site. © Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa/CIG (photo: M. Haagsma).

Results of the 2021 season cover a broad chronological timespan of human activity, from the Neolithic to pre-Modern periods; pottery was collected, amounting to 7,632 pieces and weighing a total of 182kg. Other artefacts gathered include lithics and bone remains likely to be human. Perhaps most notably, the 2021 season yielded monochrome ceramics dating to the later phase of the Early Neolithic/early phase of the Middle Neolithic (late fifth millennium BC) and a few fragments of figurines, including part of a seated female (Fig. 3.8 ) and a terracotta animal head, originally part of a vessel (Fig. 3.9 ). The majority of ceramics and rooftiles from the survey were dated to the historic and late historic periods (especially Hellenistic/Roman, Late Roman, and Medieval).

3.8. Terracotta fragments of a Middle Neolithic figurine. © Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa/CIG (photo: M. Haagsma).

3.9. Terracotta head of an animal, originally part of a vessel. © Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa/CIG (photo: M. Haagsma).

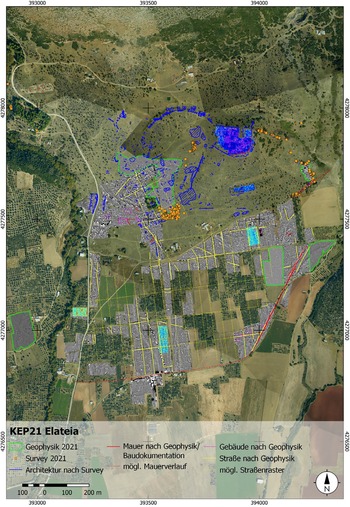

Katja Sporn (DAI) and Petros Kounouklas (Ephorate of Antiquities of Phthiotis and Evrytania) report on the 2021 season of the joint Greek–German programme Kephissos Valley Project (ID18181). The programme, which started in 2018, studies the development of settlements and their respective areas of activity during antiquity in the context of the area’s natural landscape. Central to these investigations is the question of the effects that climatic change has had on the use of land and the relocation of the settlements on the two sides of the river. The research programme, which focuses on a 145km2 section in the middle of the river valley of the Phocian Kephissos, continued successfully in 2020 and 2021 – albeit in limited scope due to the pandemic. The work in Elateia, the largest city of the Phocaeans, prioritized the mapping of preserved architectural remains – on the one hand of structures preserved on the surface, with the help of architectural study, and on the other hand of structures located below the surface of the earth, with the help of geophysical survey.

Jutting out from the fortified acropolis of Elateia, with its late antique settlement, two walls with a southeast and southwest direction extend towards the valley (Fig. 3.10 ). Square towers define the course of the walls. The excavations of the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich in and around the area of Elateia have focused on evidence related to the presence of a Roman army in the region. From four test sections on the acropolis of Elateia, it has come to light that the site was completely restructured and rebuilt in the second half of the fourth century AD. Significantly, some of the deepest levels of stratigraphy were dated to the late Middle Bronze Age, documenting, for the first time, the prehistoric habitation of the hill.

3.10. Mapping and results of research at the ancient polis of Elateia until 2021. © DAI.

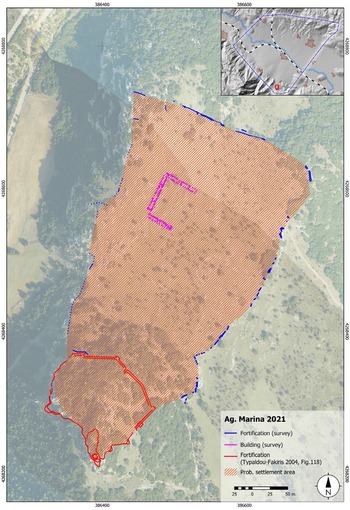

South of and above the village of Agia Marina, the Kephissos Valley Project reports on the extensive works carried out at the ancient city located on the slope of Mount Parnassos (Fig. 3.11 ). The settlement stands out for the fact that many ancient building remains are preserved above the ground, including walls, streets, conduits, etc. In 2021 large areas were cleaned and its agora was discerned for the first time, also clearly visible via orthophotography and LiDAR. Three connected constructions, which form a Π-shape and surround the aforementioned agora (55m × 45m), have been identified. As in neighbouring Elateia, it was possible to ascertain, through cuts in the bedrock, the foundation of the wall. However, in this case, there were no towers at regular intervals, and the rocks making up the wall are polygonal stones. Future test sections are expected to contribute to the dating of the city of Agia Marina, often identified with the ancient cities of Patronis or Ledon.

3.11. Acropolis and polis of Agia Marina. © DAI.

Alexandra Charami (Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia), Brendan Burke (University of Victoria), and Bryan Burns (Wellesley College) report on the five-week season in 2021 at Eleon, part of the Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project (ID18175), comprising geophysical survey and artefact study. The project is a synergasia between the CIG and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia. Due to the brevity of the season, the team limited themselves to conducting geophysical survey of the unexcavated areas of the acropolis with magnetometry and resistivity/resistance survey. The main aim was ‘to survey the area between the fenced excavation block on the eastern side of the acropolis and the medieval tower on the western edge of the acropolis…and then to examine the area south of the excavation trenches’ (Burke, Burns and Charami Reference Burke, Burns and Charami2021). The gradiometer survey covered 1.97ha, encompassing most of the acropolis. Various anomalies were brought out in the survey results, among which the most apparent was located 25m west of the polygonal wall. During the study season, the macroscopic examination of Late Bronze Age pottery fabrics took place, confirming the presence of Euboean, Attic, and Theban groups. There was also a focus on osteology, which revealed that the remains from Tomb 10 represent three individuals: Individual 1 is a subadult that was laid in the middle to western side of the tomb; Individuals 2 and 3 represent two young adults whose remains had been moved to the eastern wall of the tomb and were mixed.

Euboea

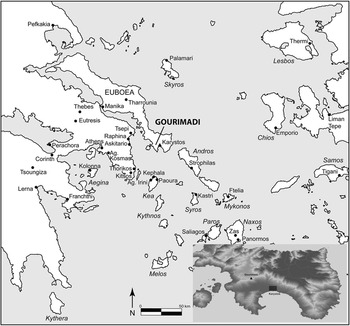

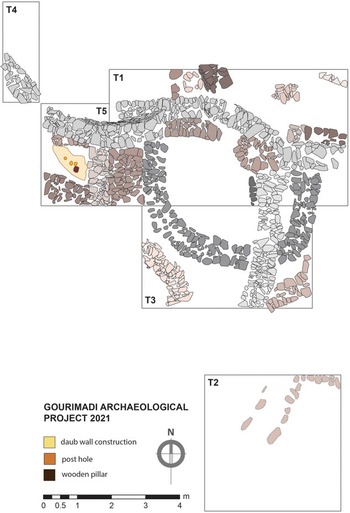

Žarko Tankosić (NIA), Paschalis Zafeiriadis (NIA), and Fanis Mavridis (EPS) report on the fourth season of the Gourimadi Excavation Project (ID17977, ID17976, ID8512) in the region of Karystos in southern Euboea (Fig. 3.12 ). The project at Gourimadi is organized by the NIA. The 2021 excavations involved the excavation of two trenches: Trench 1 and Trench 5, neither of which reached the bedrock (Fig. 3.13 ). Excavation of Trench 1 articulated further the remains of the stone-built walls excavated in previous seasons (Fig. 3.14 ), while at the same time revealing additional walls lying at lower elevation. Excavation in Trench 5 brought to light new evidence of construction in the west of the habitation, which can be dated to the end of the Final Neolithic. Notably, three aligned postholes were discovered (Fig. 3.15 ). The finds include obsidian tools of various types (scrapers, blades, and arrowheads), implying commercial relations with the Aegean islands. Ceramic sherds from the Late Final Neolithic were also found, some of which were painted. Although this setting has yet to be fully excavated, due to time constraints, it is noted that the postholes evidence the presence of building techniques different from those of stone-built masonry, which are commonly found elsewhere in Gourimadi. This is therefore the first known occurrence of such building techniques in prehistorical Karystia.

3.12. Location of Gourimadi. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/NIA.

3.13. Trench 1 and Trench 5 at Gourimadi, which were explored during the 2021 season. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/NIA.

3.14. General view of Gourimadi. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/NIA.

3.15. Gourimadi, Trench 5: the three postholes. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/NIA.

Sylvian Fachard (ESAG) and Angeliki Simossi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea) report on the beginning of a new four-year programme (2021–2024) at the Artemision of Amarynthos (ID18254) (https://www.esag.swiss/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ESAG-Public-Report-2021-gr-eng.pdf; Fig. 3.16 ). Research in 2021 focused on the earliest phases of the site’s occupation, with the study of the prehistoric settlement on Palaeoekklisies hill, as well as the Geometric and Archaic sanctuary remains. The aim of the programme is to gain a better understanding of the beginnings and development of Amarynthos. Additional intensive archaeological survey aims to help reconstruct the surrounding landscape of the Artemision.

3.16. Site plan of Amarynthos. © ESAG/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

The 2021 excavations focused on two areas. Close to the top of the hill of Palaeoekklisies, a Medieval cemetery was uncovered, as well as structures and levels of use from the Mycenaean period. Lower down, some finds of special significance came to light, including a well connected to a large stone wall, parallel to the hillside, probably dating to the Early Bronze Age (Fig. 3.17 ). In front of the wall, a small deposit of miniature vessels and clay figurines from the Classical and Hellenistic period was uncovered. These discoveries highlight the importance of the prehistoric settlement, which extended to the base of the hill of Palaeoekklisies, and perhaps beyond.

3.17. Early Bronze Age wells and walls in a trench at the foot of Palaeoekklisies hill. © ESAG/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

Excavations in 2021 also focused on the sanctuary itself, and in particular on the excavation of dedications from its interior. More than 600 objects of various types have been found in this rich deposit to date, which bear witness not only to the identities of those participating in ritual but also to the motivations behind the offering of dedications. The excavations led to the discovery also of an older sanctuary, oriented towards a horseshoe shaped altar (Fig. 3.18 ). Traces of fire on the altar and surrounding ash layers containing carbonized animal bones bring to light the sacrifices that took place here during the Archaic period.

3.18. The Archaic altar and mud-brick floor at Amarynthos. © ESAG/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

Finally, the intensive survey at Amarynthos was complemented also by archaeological terrain recognition based on LiDAR technology. Several archaeological sites from the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of the Bronze Age, as well as four previously unknown sites from the Archaic period, were discovered between Eretria and Amarynthos (ID18257). At least three demes belonging to Eretria could also be located. These sites were all established between the Hellenistic and Byzantine period. The position of the most important settlements, as well as the funerary monuments, make it possible to trace the Sacred Way from Eretria to the Artemision of Amarynthos, as well as to identify communication links.

Karl Reber (University of Lausanne), Angeliki Simossi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea), and Maria Chidiroglou (National Archaeological Museum) report on the Greek–Swiss project in the region of Styra on Euboea (ID18259) (https://www.esag.swiss/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ESAG-Public-Report-2021-gr-eng.pdf). The project focuses on a particular type of dry-stone rural building located in the mountain range of southern Euboea, the so-called drakospita or ‘dragon houses’ (Fig. 3.19 ). In 2021, the complex at Palli-Lakka was surveyed and the drakospito of Ilkizes was excavated. The few fragments found in the construction fill date it to the fourth century BC at the earliest. Numerous bones, the remains of a hearth, and pottery sherds dating to the Classical and Late Hellenistic period were found on the floor level. However, the study of this material does not yet provide enough evidence for the building’s identification. Interestingly, the architecture and location of the drakospito find close parallels with modern sheepfolds found in the region. In addition to the excavation at Ilkizes, fieldwork focused on documenting three other drakospita at Kroi-Phtocht, Loumithel-Mariza, and Palli-Lakka.

3.19. The Palli Lakka drakospito building complex in Euboea. © ESAG/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

Attica Region (incl. Kythera and Antikythera)

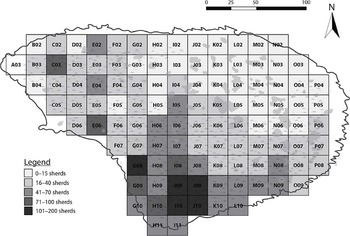

Eleni Andrikou (Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica), Anastasia Dakouri-Hild (University of Virginia), and Stephen Davis (University College Dublin) report on the second season of fieldwork for the Kotroni Archaeological Survey Project (ID18035; https://afidna.org/). During 2021, intensive pedestrian survey around Kotroni led to the identification of several new archaeological sites in the vicinity of the citadel (Figs 3.20–3.21 ). Among these is included a potentially significant prehistoric site outside the citadel itself and several Iron Age sites. According to the report, ‘7,111 sherds were recovered, of which 1,467 (20.6%) are form-diagnostic and 385 (5.4%) are useful for initial spot dating (i.e. highly diagnostic)’. The sherds are ‘strongly concentrated in the prehistoric eras, especially the Middle Helladic period (238, 61.8% of highly diagnostic finds), but also include decorated early Late Helladic, and decorated and plain Late Helladic pieces’ (Andrikou, Dakouri-Hild and Davis Reference Andrikou, Dakouri-Hild and Davis2021). Pottery from the Classical period is well-attested, followed by Roman/Roman Byzantine, Geometric, Ottoman/Early Modern, and Byzantine/Byzantine-Frankish (Fig. 3.22 ). Based on the preliminary analysis of finds, it is possible to ascertain the presence of Bronze Age occupation on several parts of the 2021 survey, and especially in the southern part of Sector W and near the top of Gaitaná (as adjudged by numerous obsidian pieces). Geometric and Archaic pottery are largely found in a small area of Sector W and Gaitaná. Classical evidence is more broadly present, particularly in the east, south, and southwest parts of the survey. The Hellenistic-Roman, Roman, and Roman Byzantine finds display a similar pattern, while occupation dating to the Byzantine, Frankish, and Ottoman appears most frequently in the east and south parts of the 2021 survey area.

3.20. The Kotroni hill near Kapandriti and Lake Marathon. © IIHSA/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica.

3.21. Tentative Bronze Age-Geometric habitation spread around Kotroni (shown here in the form of highlighted tracts). © IIHSA/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica.

3.22. A selection of ceramic finds dating from the Bronze Age to the Ottoman era. © IIHSA/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica.

In 2021, the ESAG and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands began a new research project on Mount Oros on Aegina (https://www.esag.swiss/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ESAG-Public-Report-2021-gr-eng.pdf) (Fig. 3.23 ). The first investigations of the area, carried out during the first half of the 20th century, were never followed by a detailed publication. The new research project is led by Stella Chrysoulaki (Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands), Tobias Krapf (ESAG), Leonidas Vokotopoulos (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki), Sofia Michalopoulou (Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands), and Jérôme André (University of Lausanne).

3.23. Analipsis chapel and the surrounding wall on the Mount Oros summit. © ESAG/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands.

The Mount Oros project aims to verify the diachronic use of the sanctuary, as well as its early period of cultic use, and to determine more precisely the dating of the settlement in this unique position, which likely corresponds with the period after the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces. In 2021, excavation was undertaken in the areas on both sides of the church. While on the southern side, it seems to be the case that the majority of the soil above the Mycenaean layers is fill from excavations at the beginning of the 20th century, on the north side, the soil is more or less undisturbed. It is on the north side that a noteworthy amount of Mycenaean pottery was uncovered, as well as the head of a Phi or Psi-figurine, and many thousands of tiny bone fragments bearing traces of burning. The last of these likely came from activity in relation to the altar, which is found at a higher level. The numerous ceramic offerings point to the frequency of visits to the summit already from the Middle Bronze Age, during the first half of the second millennium BC, until the Roman, Byzantine, and even modern period. Another aim of this research project is gaining a better understanding of the location of the sanctuary in the context of its environment. To this end, in 2021 a surface survey of the area took place, covering the southern, uninhabited area of the island (11km2), about 1/8 of the full terrain of Aegina. During the prehistoric, historic, and Early Modern periods, the area seems to have been utilized more intensely than in the modern period, as is demonstrated, among other things, by a second Late Mycenaean fortification, a ‘dragon house’, stone terracing, and water tanks.

Sarah Murray (University of Toronto/CIG) and Catherine Pratt (University of Western Ontario/CIG) report on the second season of the diachronic Bays of East Attica Regional Survey project (ID18083). The goals for this season were to finish the survey of the outer slopes of the Koroni peninsula, which started in 2019, and to survey the Praso islet. Intensive survey units were focused on the slopes of Koroni, as well as the undeveloped hilltop to the immediate south which connects the Koroni peninsula with the mainland (Fig. 3.24 ), where Curtius and Kaupert’s Karten von Attika (Reference Curtius and Kaupert1895) show the foundations of ancient structures. Survey on the slopes of Koroni facilitated the discovery of many substantial features that will be mapped and studied in detail in 2022, including a round tower on the outer of the peninsula that appears related to the fortification architecture on the acropolis. In contrast, artefacts encountered and collected in the units surveyed in 2021 were minimal, aside from the identification of additional LH IIIC pottery on the slopes of the acropolis and the location of a possible dump from the 1960 excavations.

3.24. Map of survey units on Koroni, 2019–2020. © CIG.

The focus of the 2021 season was surveying the islet of Praso. Praso is a low-lying islet directly to the southeast of the Pounta peninsula, which splits the bay into northern and southern sections. The survey on Praso documented a dense scatter of pottery, tile, and other artefacts (Fig. 3.25 ), making evident the diachronic nature of habitation in the Porto Rafti area; finds ranged from the Final Neolithic to the Byzantine periods. According to Murray and Pratt (Reference Murray and Pratt2021), the diachronic diversity of archaeological finds from Praso stands out within the archaeology of Porto Rafti, since most known sites around the bay show intensive use only in one or two periods. The survey on Praso represents a significant contribution for understanding the islet’s true archaeological significance.

3.25. Sherd densities from feature a003 (Praso). © CIG.

A diverse array of artefacts is present throughout nearly the entire surface of the islet. Noteworthy concentrations of ceramic and tile were identified on the flat apron extending over the western third of Praso and along the central part of the south-facing slope. A large quantity of prehistoric pottery was observed eroding out from below the later material near the islet’s southern shore, providing evidence for the presence of Classical/Hellenistic and prehistoric deposits lower down in the islet’s stratigraphy. Across the survey area, finds from the LH IIIC, Hellenistic, and Late Roman period were generally most ubiquitous. In addition to pottery, tile, lithics, and a total of 320 objects categorized as ‘other’, ranging from ‘fragments and lumps of metal (iron, bronze, and lead), pieces of lamps (Fig. 3.26 ), fragmentary terracotta anthropomorphic and zoomorphic Bronze Age figurines (Fig. 3.27 ), pyramidal loom weights and spindle whorls, glass vessel fragments, and large quantities of material associated with both ceramic (pottery and tile) and metallurgical production’ were found (Murray and Pratt Reference Murray and Pratt2021). These moveable finds from Praso highlight the human occupation of the islet across different periods. Likewise, the range of finds suggests multiple and changing uses for the islet over time, spanning from ritual to industrial activities.

3.26. Lamps from Praso islet. © CIG.

3.27. Two joining pieces of a Bronze Age zoomorphic figurine. © CIG.

Jutta Stroszeck (DAI) reports on work conducted in 2021 at Kerameikos (ID17197). An area west of the Kerameikos Street was investigated, which had previously been excavated in the 1940s and recognized as a workshop area. Pottery kilns were also found in the N part, and the area was dated to the fifth century BC.

For a sixth year, and in the context of the new three-year project (2020–2022), underwater research on the eastern shores of Salamis (ID18173) continued, as part of a collaboration between the Institute of Marine Archaeological Research (I.EN.A.E.) and the EUA. Angeliki Simossi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea) and Yannos G. Lolos (Ioannina) report on discoveries made on the first programme of underwater research undertaken in 2021 in the Ambelakia-Kynosoura area. The underwater survey, in its first phase, was focused on the northern portion of the head of the modern-day Gulf of Ambelakia, where there had been systematic study of submerged remains belonging to the ancient polis of Salamis, which extends on the southern side of the Pounta peninsula. A large section of the Classical city wall was found, oriented north–south (Figs 3.28–3.29 ). The structure was investigated in 4m × 4m excavation units, over a total area of 50m2. Towards the south, the wall was followed for 16m, and two construction phases were identified of the fourth century BC. The latter phase was 3m thick and contained large worked stones; to the west of the wall, parts of the ancient construction had been incorporated into the Early Modern jetty. This wall is so far the only systematically excavated part of the ancient city’s fortifications. Pottery of the Hellenistic and Roman periods came from the most recent excavation, along with some Attic pottery of the Late Classical period (Fig. 3.30 ). Amphora sherds were found, as well as some marble objects. More generally, incorporating also the results of the previous five years of excavation, the orientation of the wall has been established as following along the harbour of the Classical-Hellenistic polis of Salamis. It makes up a crucial portion of the entire fortification system of the polis of Salamis, whose perimeter can now be more or less entirely reconstructed, based also on the studies of 19th-century archaeologists W.M. Leake, H.G. Lolling, and A. Milchhöfer.

3.28. Ambelakia Bay. Aerial photograph of the research area, with a view of part of the submerged Classical city wall. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA/Institute of Marine Archaeological Research (photo: E. Kroustalis).

3.29. Ambelakia Bay. Partial view of the E face of the submerged Classical city wall. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA/Institute of Marine Archaeological Research (photo: C. Marabea).

3.30. Ambelakia Bay. Examples of black-painted Late Classical pottery. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA/Institute of Marine Archaeological Research (photo: C. Marabea).

The second phase of underwater research focused on the inner portion of Ambelakia Bay, in the anchorage area of a large part of the Greek fleet on the eve of the naval battle of 480 BC (Fig. 3.31 ). Test excavation sections were carried out at three points of interest, among the many that have been identified by the intensive geophysical research of previous years by George Papatheodorou (University of Patras). From the exploratory sections, which reached a depth of 1–2m in the silt of the sea floor, evidence emerged that will contribute to the study of local sedimentation, the reconstruction of the paleogeography of historical Ormos, and to the more precise delineation of its coastline during the Classical period. A dense accumulation of stones mixed with fragments of vases and ceramics from various periods (including Hellenistic amphorae) came from Section 3, on the northwest side of the present cove. This is probably drifted mixed material, very similar to that from the nearby excavation of the wall and other submerged remains, which appear to be related to activities on land during antiquity.

3.31. Ambelakia Bay. View of the research area. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA/Institute of Marine Archaeological Research (photo: Y. Lolos).

In 2021 the excavations at ancient Kalaureia, Poros (https://www.sia.gr/en/articles.php?tid=546&page=1), were continued by the SIA in Area L, part of the site associated with the ancient settlement outside of the sanctuary of Poseidon. In 2021, a larger segment of stone Feature 3, which seems to consist of several walls enclosing a surface formed by a stone packing, was excavated. It was not possible, however, to expose the full feature due to the presence of Roman walls positioned directly above it (Fig. 3.32 ). The Roman walls provide useful information on the structural development of Area L in the Roman period. A thick construction fill dating to the late first century BC or first century AD was uncovered in several areas. This fill seems to have served as the foundation for a new level, with some of the older walls reused, and with new stretches of wall built on top of the previous structures. Further evidence for the stratigraphy and structuring of the chronological phases was brought forth by the exposure of a pebble floor (first found in 2018) in the northern part of the trench. This is preliminarily dated to the same period as the fill. Although much work remains to be done to establish a firmer chronology and understanding of the building phases in Area L, the 2021 excavations have improved our understanding of the function and uses of the buildings over time.

3.32. Kalaureia: feature 3 (formed by lower walls) with the newly exposed Roman walls situated above it. South orientation. © SIA.

Dimitris Kourkoumelis (EUA) reports on discoveries made in 2021 during the excavation of the Mentor shipwreck at Kythera (ID18169), as part of an ongoing underwater archaeological investigation (Fig. 3.33 ). Recent discoveries (Kourkoumelis and Tourtas Reference Kourkoumelis, Tourtas and Simosi2018) contribute important information on how the ship was built, while also offering a glimpse of the lives of the people on board. The first sector excavated was the keel on the north side, with the aim of clarifying details relating to construction. Pieces of military uniform, furniture, and a gold ring decorated with flowers and dots (identical to one found in 2019) were among some of the objects that are thought to have belonged to the crew. The second sector investigated covered almost the entire length of the south end of the ship, with a focus on exploring the hull and making observations and measurements on the structure of the ship. Of particular interest were two large sections of rope and two Dutch coins, issued in 1777 and 1800 (Fig. 3.34 ). Part of a theodolite (Fig. 3.35 ) was also uncovered, corresponding with fragments located in 2013 and 2015. It is possible that this object belonged to William Martin Leake, who was travelling on this vessel. The vessel was owned, however, by Lord Elgin, who is thought to have been using it to transport antiquities from the Athenian Acropolis to the United Kingdom (Leontsinis Reference Leontsinis2010).

3.33. Mentor shipwreck: general view of the area excavated in 2021. © V. Tsiaris / Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA.

3.34. Mentor shipwreck: Dutch gold coin (ducat), issued in 1800. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA.

3.35. Mentor shipwreck: part of a theodolite, after cleaning. © P. Vezirtzis/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA.

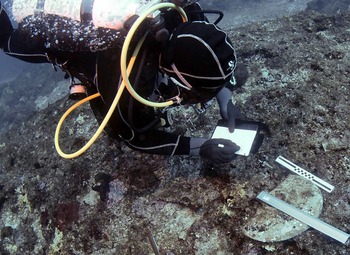

Angeliki Simossi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea) and Lorenz Baumer (ESAG / University of Geneva) report on the results of a survey carried out on the Antikythera shipwreck (ID15659), launching a new five-year underwater research programme on the context (2021–2025). The research project is also under the auspices of the EUA and the president of the Hellenic Republic. Work in 2021 focused on the creation of a full 3D photogrammetric model of the shipwreck, which sank in the first century BC. One of the key goals of the project is to identify the existence of any remnants of the Antikythera mechanism, especially in the area where the ship has been covered over as the result of a landslide. Research is also focused on the possible connections between the vessels and people on board vessels A and B (Fig. 3.36 ). Another key aim is the discovery and collection of parts of the cargo, and/or any human skeletal remains. The most important find in 2021 was a marble statue trapped under a heavy boulder. Smaller wooden and copper structural elements of the ship were retrieved, as well as small pieces of ceramic that will be useful for dating the cargo.

3.36. Identification and documentation of pottery from the Antikythera shipwreck. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

Especially rich in finds was the second season of the underwater archaeological excavation of the Antikythera Shipwreck in 2022 (ID18172; https://www.esag.swiss/return-to-antikythera-2022/) (Fig. 3.37 ). Among the new finds are a marble statue base and a larger-than-life-size marble head of a bearded man (Fig. 3.38 ) that preliminary observations suggest is associated with Herakles of the so-called ‘Farnese’ type. It is likely that it belongs to the headless statue (inv. no. 5742) in the National Archaeological Museum, which was discovered by sponge divers in 1900. Two human teeth were also found, which will undergo DNA analysis that will hopefully give further indication with regard to sex and other genetic features of the person(s) to whom they belong. Many items belong to the ship’s equipment, such as bronze and iron nails, as well as the leaden (tip?) of a wooden anchor, and many other corroded masses of metal which will be examined with X-ray.

3.37. Excavation in a section of the Antikythera shipwreck. © ESAG / Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

3.38. Discovery of larger-than-life marble head. © ESAG / Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea.

Peloponnese

Andreas Vordos (Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaea) and Elisabetta Borgna (University of Udine) report on the 2021 excavations from Trapeza (ID15660; https://www.culture.gov.gr/el/Information/SitePages/view.aspx?nID=3999), 8km southwest of Aigio, which brought to light important objects (Fig. 3.39 ). The site is associated with Rypes, a city that flourished in early historical times, and founded the colony of Crotone in Magna Graecia. Excavation focused on the site’s Mycenaean necropolis, located on the southwest slope of the plateau, and on the ancient road that led to the acropolis in the historic periods. Graves consist of chamber tombs carved into soft, sandy soil. The graves were used extensively during the first Palatial period, and significant reuse dates to the 12th century BC, when the tombs were reopened repeatedly, and until the end of the 11th century BC. Assemblages from the necropolis included pottery, seal stones, and beads and jewellery made of various materials (glass, faience, gold, carnelian, rock crystal). Significant among these are also gold amulets in the form of bulls (bucrania). These finds indicate trade contacts with the eastern Aegean and with Cyprus. The rectangular chamber of Grave 8 (Fig. 3.40 ) yielded three layers. In the first layer, dating to the 12th century BC, three burials were found associated with stirrup jars. Bones from an earlier burial had been removed with great care and placed in two parallel deposits against the back wall of the chamber; at the top, three painted clay alabastra and an amphora date the first burials to the 14th century BC. Among the bones and grave goods that accompanied these burials, a clay horse figurine and an extremely well-preserved bronze sword were also found. At the base of the piles of bones, two more bronze swords were found, entirely intact apart from their wooden handles, which nevertheless are partially preserved. The swords were of different types (Sandars D and E) and date back to the peak of the Mycenaean palaces. These finds, and spears of the same period found in nearby graves at Trapeza, are distinctive from graves found elsewhere in Achaea and suggest the dependency of the local community on powerful centres, as the weapons are probably the products of palace workshops. The location of the Mycenaean settlement of Trapeza remains unclear. It is possible that, during the early use of the necropolis, the settlement was on a hill about 100m to the south. In 2021, in parallel to the work at the necropolis, excavations revealed part of a building, comprising a wide rectangular room, with a hearth and pottery of the 17th century BC.

3.39. Bronze sword among the bones of the burial deposit excavated at Trapeza. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaea.

3.40. Excavation of chamber tomb 8 at Trapeza. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaea.

The Ephor of Antiquities of Messenia, Evangelia Militsi, reports on excavations at Ypapanti square in Kalamata (https://www.messinialive.gr/oi-archaiotites-tis-plateias-ypapantis-kai-orthi-diacheirisi-tous-simantiko-zitima-politismou-gia-tin-kalamata/). Back in 1964–65, Nikos Gialouris had brought to light the walls of a public building, ca. 100m × 20m, in the same area. It seems that it was in this part of the ancient city of Pharai that the town centre was located, with the market and the related public buildings around it.

Elena Korka (Director General Emerita of the General Secretariat of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage at the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports) reports on discoveries made during the systematic excavation at ancient Tenea (ID17186) at Chiliomodi, Corinth, in 2021. The aim of this year’s work was to complete the excavation of the rooms of the Roman bath (Fig. 3.41 ) and to investigate the commercial buildings identified in 2020. The finds from the excavations bear witness to organized settlement in the area of Tenea as early as the third millennium BC. The quality, as well as the quantity, of the finds highlight the existence of a well-organized settlement placing Tenea on the map of Early Helladic sites of the northeastern Peloponnese.

3.41. Aerial photographs of the 2021 excavations in Ancient Tenea, demarcating areas currently under investigation. © Elena Korka.

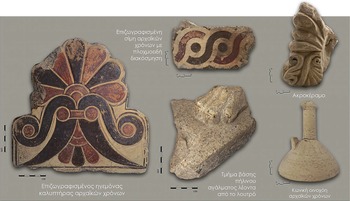

Behind the arch of the western caldarium (warm room for bathing), the Vespasian baths (public toilets) were revealed. A raised floor was found made of clay slabs and pipes re-enforced with clay slabs and rooftiles, serving as sewage drainage. Eight coins were uncovered, the earliest of which dates to the end of the second century AD, with others to the third century AD and the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth century AD. Among these were also finds from Roman times, such as a bronze ring, a bone fibula, lamps, and a marble colonnade. Subsequently, to the north of the caldarium, the third praefurnium (furnace providing underfloor heating) of the baths and the spaces that served to store wooden materials for its operation were excavated. Within these sections, among other finds from Roman times, fallen architectural members of the Archaic period were brought to light, as well as a cover tile and a seme (the upturned edge of a roof which serves as a gutter) painted with a red-and-black guilloche border (Fig. 3.42 ). These elements probably come from a building of the Archaic period, which is presumed to be located within the vicinity of the monument, and from which important architectural members have been identified in previous excavation periods. The bath complex covers a total area of some 800m2, and includes three caldaria with arched ends, which have alvei (small pools) inside them, as well as underfloor and wall heating, two cold and warm bath rooms, resting areas and footbaths, Vespasians toilets, a three-part water filtration tank, rainwater collection tank, a water tower, and fuel storage areas. The public baths of Tenea seem to have been founded shortly before the middle of the second century AD, with two new building phases following, one in the fourth century AD and one in the fifth century AD, during which interventions, repairs, and extensions were carried out.

3.42. Finds from the Archaic period at ancient Tenea. © Elena Korka.

To the east of the bath, the archaeological investigation of the areas of commercial activity continued. These areas extend both to the north and to the south, creating building blocks delimited by surrounding streets and passages. The excavation of the above areas helped significantly in mapping the urban fabric of the city, which is constantly being defined with greater clarity. Within the rooms, objects relating to commercial activity (Roman coarse ware pottery, as well as glass and fine ware vessels for cosmetics, lamps, etc.) were found. Also excavated were 179 coins dating from the end of the second century AD until the middle of the sixth century AD (Fig. 3.43 ). The continuation of excavations in the room where the hoard of 30 gold coins of the emperors Marcian, Justin I and Justinian were found in 2020 yielded more than 120 new coins. In the same room, at a lower depth, an earlier building of the late Hellenistic period was revealed, with a north–south orientation. The building appears to extend beyond the boundaries of the excavated area and will be further investigated during the next excavation period.

3.43. Coins from ancient Tenea dating from the second to fourth centuries AD. © Elena Korka.

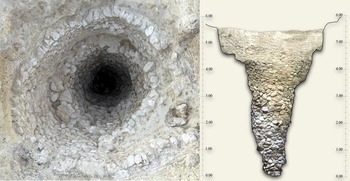

The most significant discovery of the season, an Early Bronze Age deposit (Fig. 3.44 ), was brought to light 45m north of the bath complex and 2m below the ground. It was covered in a thick layer of stones and a pile of ceramics, and was itself lined with stones. The deposit was elliptical in shape, with dimensions 3.3m × 3.1m, and descending to 6.8m, gradually narrowing at the end. Finds worthy of mention from the layer covering the deposit and its near vicinity are human and animal clay figurines, bases of storage vessels with woven basket impressions and one base with a leaf impression (Fig. 3.45 ), portions of clay hearths with incised decoration, feet of tripods, jugs, numerous fragments of open vessels, plates (including footed and ring-based examples), handles of storage vessels, etc. Significant is also the discovery of a large number of spindle whorls, as well as loom weights, obsidian flakes, and tools (Fig. 3.46 ).

3.44. The Early Helladic deposit at ancient Tenea. © Elena Korka.

3.45. Select finds from the Early Helladic deposit. © Elena Korka.

3.46. Obsidian cores, flakes and tools, clay and stone whorls and weights, a metal and a flint tool from the Early Helladic deposit. © Elena Korka.

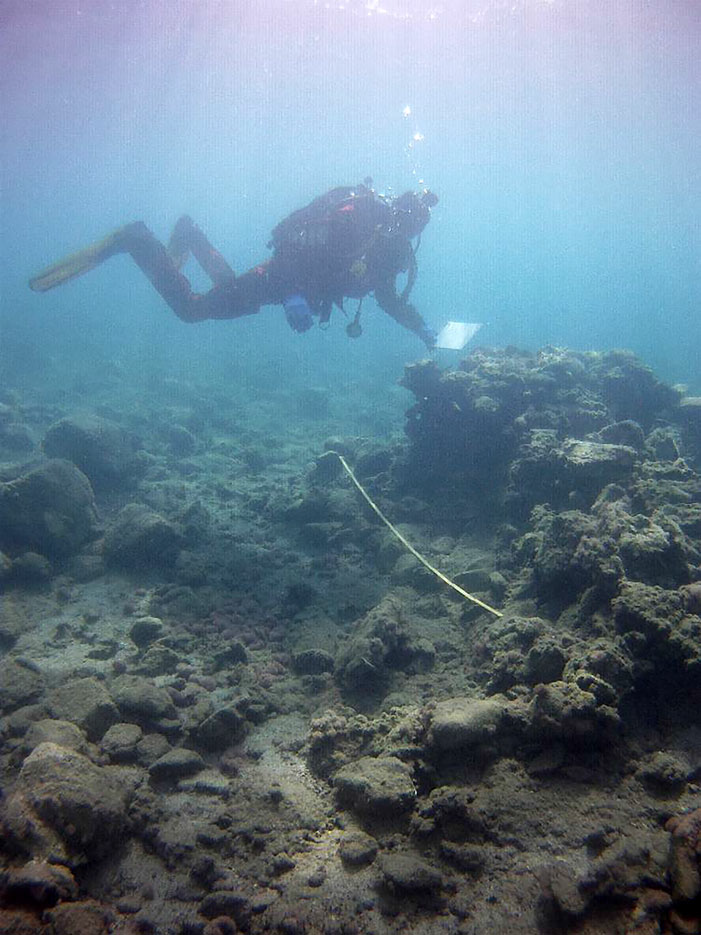

A pilot underwater archaeological investigation (Fig. 3.47 ) took place in October 2021 in the waters outside Asine and Tolon in the Argolid (https://www.sia.gr/en/articles.php?tid=669&page=1). The project was a collaboration between the EUA, the SIA, and Stockholm University, with participants also from the University of Gothenburg and the Nordic Maritime Group. The project had as its primary aim for the season the documentation of the seabed with an advanced (side-scan) sonar, and to then subsequently carry out dives at identified anomalies. The project also investigated the seabed around the Kastraki promontory, outside the boundaries of the ancient settlement. Due to the rise in sea level outside the Kastraki promontory over the past millennia, water erosion has led to the partial collapse of the Hellenistic city wall into the sea. The accretion of mud and other stones makes it challenging to ascertain when underwater formations are natural and when they are manmade. Comprehensive sonar investigation, however, has brought forth evidence that Asine’s harbour in fact comprised a larger area than previously thought, stretching from the Kastraki promontory to the strait between Tolon and Romvi island. This entire area was mapped with sonar, and several anomalies on the seabed were investigated, although these turned out to largely be modern remains or natural objects. The diving team investigated the water on both sides of the Kastraki promontory. The area was documented with photogrammetry, drone photography, and underwater sketches. The process of sedimentation, as well as the sandy seabed, may explain the absence of shipwrecks, anchors, and/or cultural layers. A built ‘platform’ of rocks and small stones (Fig. 3.48 ) appears to have been directly connected with the ancient settlement at Asine. In the best preserved northern part of the ‘platform’, several room-like structures came to light. The structures on top of the ‘platform’ are challenging to interpret as the wall remains are eroded and deformed.

3.47. Diver Niklas Eriksson participating in photogrammetry and traditional drawing underwater at a depth of 2.5m. © Staffan von Arbin/SIA/EUA.

3.48. A built stone platform with presumed building remains west of the Kastraki promontory. © Niklas Eriksson/SIA/EUA.

Alcestis Papadimitriou (director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Argolid) reports on the discovery of a life-sized female marble statue of the Roman period, found last December in the agora of ancient Epidauros (ID17185). The statue was found intact apart from its hands and head, which probably broke when the statue fell. It was discovered after the main excavation period at Epidauros during the summer, when a small part of the back of the statue came to light following heavy rainfall (Figs 3.49–3.50 ). The pose and form of the statue is typical of either a married woman or of Hygeia, wife or daughter of Asklepios. The statue is thought to date to the Roman Imperial period.

3.49. Statue of a woman in a chiton. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Argolid.

3.50. Findspot of Roman statue in ancient Epidauros. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Argolid.

Since 2015, systematic excavations have been taking place in the sanctuary of Asklepios by the National Kapodistrian University of Athens, under the direction of Vasilis Lambrinoudakis. Close to the ancient theatre (today known as ‘little Epidauros’), which was found inside the ancient agora, an important well installation has been excavated, connected also to a fourth century BC peribolos, which in the Roman period took on a new form with the addition of a stoa on the west and a ‘round’ building on its northern side. Details have come to light that strengthen the association of this structure with the temenos (sacred precinct) of Asklepios mentioned by Pausanias (Paus. 2.27–8) in relation to the polis of Epidauros.

North Aegean

The EUA and the Archaeology Department of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki report on the results of the underwater exploration of the small islet of Agios Petros (https://digitalculture.gov.gr/2022/06/apotelesmata-tis-enalias-sistimatikis-archeologikis-erevnas-sti-nisida-agiou-petrou-alonnisou/), off Alonissos. The research was carried out within the framework of the first year of the approved five-year programme (2021–2025). Exploratory underwater research (Figs 3.51–3.52 ) has been completed in the submerged part of the Neolithic settlement of Agios Petros, located in the homonymous bay of Kyra-Panagia, north of Alonissos. This is an important site among the islands of the Aegean, the findings of which give a complete archaeological picture of the first agricultural groups that settled permanently in the Greek area, shortly before 6000 BC. The main objective of the underwater archaeological excavation was to uncover the image presented by the submerged part of the Neolithic settlement (due to the gradual rise of the sea level), to record the archaeological remains that have been preserved until today, and to make an assessment regarding their future investigation.

3.51. Divers undertaking underwater archaeological research at Agios Petros, Alonissos. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA.

3.52. Divers exploring the seabed at Agios Petros, Alonissos. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA.

The identification of visible anthropogenic remains (technical stone piles, walls, and pottery, at a depth of 5–7m) was particularly important. The nature of these is expected to be clarified in the context of a future excavation. Equally noteworthy was the preservation of archaeological embankments, mainly below the sandy bottom, as shown by the core samples taken. The possibility offered by the continuation of underwater archaeological research at Agios Petros, the earliest sunken island settlement in the Aegean, is expected to reveal important aspects of the life of the first communities and navigation in the Aegean islands.

Giorgos Koutsouflakis (EUA) reports on discoveries made in 2021, during the sixth season (2015–2021) at the Fournoi Archipelago (ID18031, ID8147, ID6598, ID6586). A Byzantine period shipwreck was investigated near Cape Fygou (Aspros Kavos), north of the settlement of Kamari on the east coast of Fournoi, 43–48m below the surface. This ship was considered the most scientifically interesting of 58 shipwrecks found at Fournoi, due to its near-complete condition and the broad variety of cargo it was carrying, including six different types of amphorae from the Black Sea region. A large part of the cargo seems also to have been made up of pottery (tableware) from Phokaia. Underwater archaeological investigations were conducted on the western part of the ship’s perimeter (the shallower side of the wreck). A test section was also opened in the northwest corner to establish the wreck’s stratigraphy. Fifteen buried amphorae were uncovered (Fig. 3.53 ), among which some were attributed to Sinope. Ceramics, some wood, and part of a scaffold were also found. The ceramics proved instrumental for dating the shipwreck to between AD 480 and AD 520, likely during the reign of Anastasios I (AD 491–518).

3.53. Divers on the seabed examining buried amphorae. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: EUA.

South Aegean

Alex Knodell (Carleton College), Dimitrios Athanasoulis (Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades), and Žarko Tankosić (University of Bergen) report on the third season of the Small Cycladic Islands Project (SCIP) (ID18178), which carried out intensive pedestrian survey and architectural documentation in the uninhabited islets of the western Cyclades and Syros. SCIP is a regional and diachronic archaeological survey of various small (most under one km2 in area), currently uninhabited islands in the Cyclades. SCIP aims to investigate archaeological evidence of past human activities on islands that are currently uninhabited (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2020; Athanasoulis et al. Reference Athanasoulis, Knodell, Tankosić, Papadopoulou, Sigala Diamanti, Kourayos and Papadimitriou2021). The 2021 field season included comprehensive surveys of 18 islands close to Kythnos, Seriphos, Siphnos, and Syros (Fig. 3.54 ). Each island was surveyed using a combination of systematic fieldwalking, as well as environmental study and architectural documentation. The islets surveyed revealed a broad range of human activity from prehistory to the present. Places of particular interest were subject to more detailed site-based collections, which allowed for the amassing of information about the history of occupation and use on each island, building upon previous years’ work on Seriphopoula and Kitriani by members of the Ephorate of Antiquities (Pantou and Papadopoulou Reference Pantou and Papadopoulou2005; Papadopoulou et al. Reference Papadopoulou, Pantou, Chrysoverghi, Giannakopoulou and Bassiakosforthcoming).

3.54. Islets surveyed in 2021 (map by Alex Knodell). © NIA/Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades.

The results of survey on Agios Loukas, Seriphopoula, Piperi, Kitriani, and Didymi revealed a complex history of diachronic use, while other islets had minimal evidence for human activity. Neolithic and Early Bronze Age sites were able to be identified on the large islets of Seriphopoula, Piperi, and Kitriani, while Classical-Hellenistic towers were documented on both Piperi and Seriphopoula. At Kolonna, extensive remains of the Classical, Roman, and Byzantine periods were noted at the site of the Church of Agios Loukas (built in 1779). On Kitriani, intensive survey provided new insights about the 11th-century church of Panaghia Kypriani (Fig. 3.55 ), which contains the only known Middle Byzantine wall paintings of Siphnos (Chatzidaki Reference Chatzidaki2001). On the island of Didymi (also known as Gaidouronisi), renowned for its 19th-century lighthouse (Fig. 3.56 ), sites of the Archaic to Early Roman period came to light. Finally, the project also noted the large quantities of modern garbage on many islands, highlighting the high levels of risk to such marine and small-island environments, which are already experiencing challenges due to climate change and encroaching development.

3.55. Church of the Panaghia Kypriani on Kitriani, with Siphnos in the background. © NIA / Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades.

3.56. Didymi Lighthouse, Syros with Ermoupolis in the background © NIA / Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports: Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades.

Crete

Pietro Militello, director of the ongoing mission at Phaistos (University of Catania/ Ca’ Foscari University of Venice/ Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale – Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche; https://www.scuoladiatene.it/component/k2/nsa-ia-notizie-degli-scavi-della-scuola-archeologica-italiana-di-atene-2022-1.html) reports on finds from the recent season. The mission is part of the new five-year plan that aims to address some crucial aspects of the settlement and environmental history of Phaistos, from the Neolithic to the first millennium BC. In 2022, the area to the west of the palace was investigated with three new trenches (Figs 3.57–3.59 ), while Evi Margaritis (Science and Technology in Archaeology and Culture Research Center, The Cyprus Institute) focused on reconstructing the paleo-environment and diet. Architectural studies were carried out, focusing on the materials used, masons’ marks, and the reconstruction of elevation, while a topographic group focused on creating relevant cartographic documentation.

3.57. Phaistos, Trench 1. Protogeometric compartment NN, with the wall structures from the destruction phase and the phase post-destruction visible. © SAIA.

3.58. Phaistos, Trench 2. Hellenistic Room 1 from the south. © SAIA.

3.59. Phaistos, Trench 3. Hearth and Geometric wall, from the south. © SAIA.

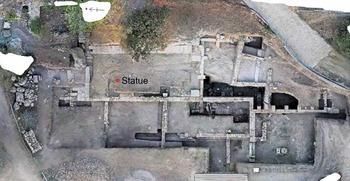

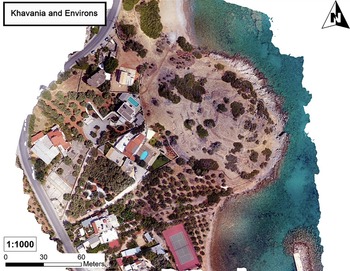

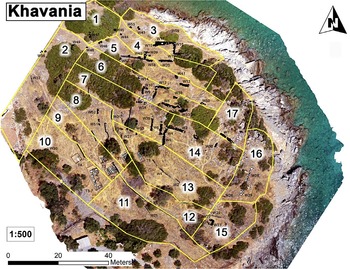

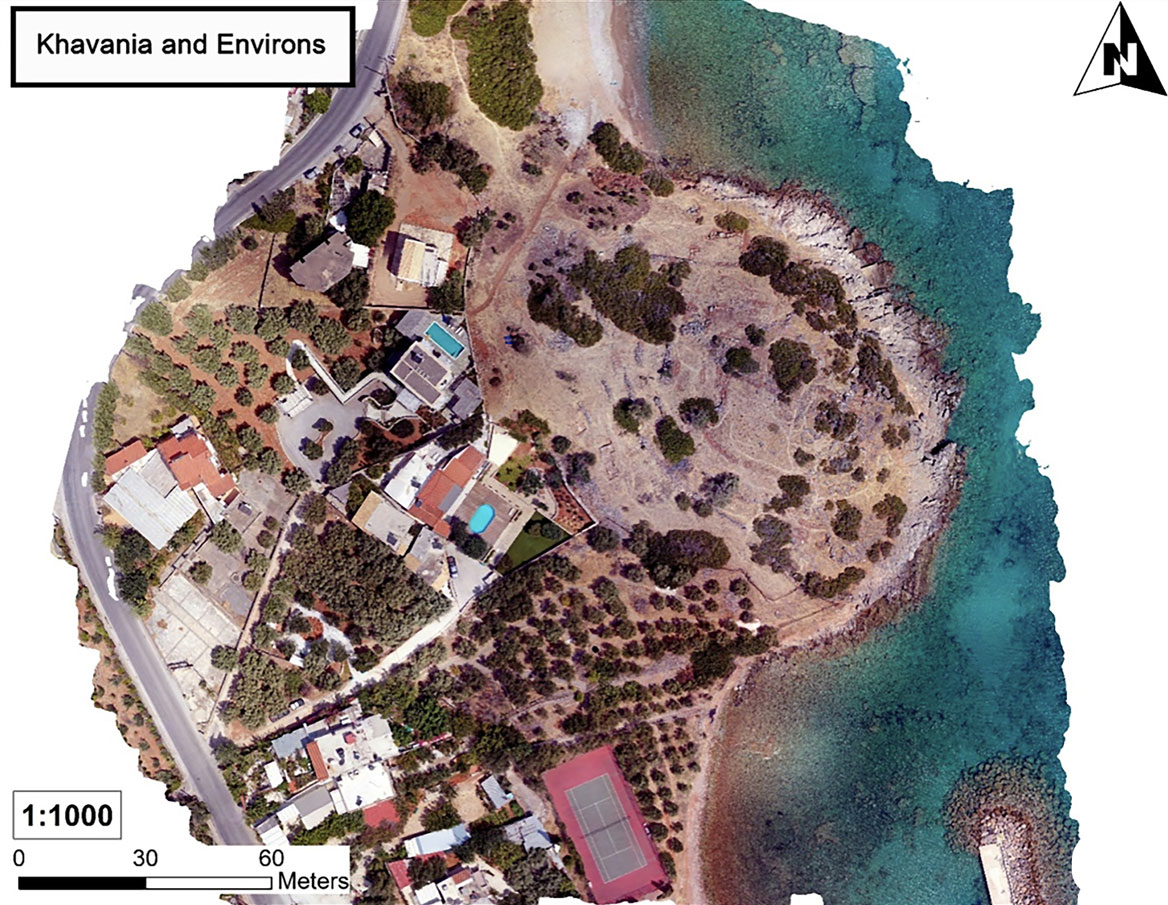

D. Matthew Buell (CIG/Concordia University) and Rodney D. Fitzsimons (CIG/Trent University) report on the Khavania Topographic and Architectural Mapping Project (ID18054) (Figs 3.60–3.61 ). The overall goal of the project is to study the development of the Bronze Age site at Khavania, considering in particular its local, East Cretan, and broader, island-wide socio-political and economic impact. During the 2021 session, which continued to be affected by the pandemic, cleaning and documentation of architectural features took place, employing UAV-captured aerial imagery. The Khavania team also conducted intensive pedestrian survey, aiming to determine the general settlement history of the site and its spatial and chronological patterning. According to Buell and Fitzsimons (Reference Buell and Fitzsimons2021): ‘24 new architectural features were discovered, including 19 previously identified features and five newly identified ones. These were all drawn, photographed, and integrated into the overall site plan. To date, 77 architectural features, including a quarry [Fig. 3.62 ], have been identified and fully documented on the Khavania peninsula.’ Examination of the architectural features has allowed nearly all of these to be identified as walls made of local materials. Furthermore, a minimum of three independent buildings have also been identified on the Khavania peninsula. The remains of a large structure (ca. 100m2 measurable extant area) on the northern slope of the peninsula stands out, in particular its impressive northern façade, which has a maximum width of ca. 1.8m (average width is 1.4m). It is not possible at this time to make any interpretation regarding the building’s dating and function.

3.60. Khavania and the immediate surroundings. © CIG.

3.61. Intensive survey areas on Khavania. © CIG.

3.62. Khavania, quarry face. © CIG.

The intensive pedestrian survey resulted in a diverse array of finds: 1,603 ceramic sherds, 19 groundstone implements, 17 mud-brick fragments, nine bone fragments, eight pieces of obsidian (chipped), and one fragment of a Second World War-era mortar shell. One particularly remarkable find, which came from Area 4, was the stem of an LM II goblet, described as having the ‘very pale buff fabric typical of Knossian wares’ (Buell and Fitzsimons Reference Buell and Fitzsimons2021). The short and hollow stem, as well as its brownish lustrous paint, are typical of LM II vessels. Preliminary analysis suggests there may be other associated LM II sherds from this context. The significance of the find comes from the fact that LM II vessels are rare in East Crete, and rarer still in the Mirabello region. The presence of LM II materials at Khavania may therefore indicate that the site was in fact occupied during this period and interacting with Knossos.

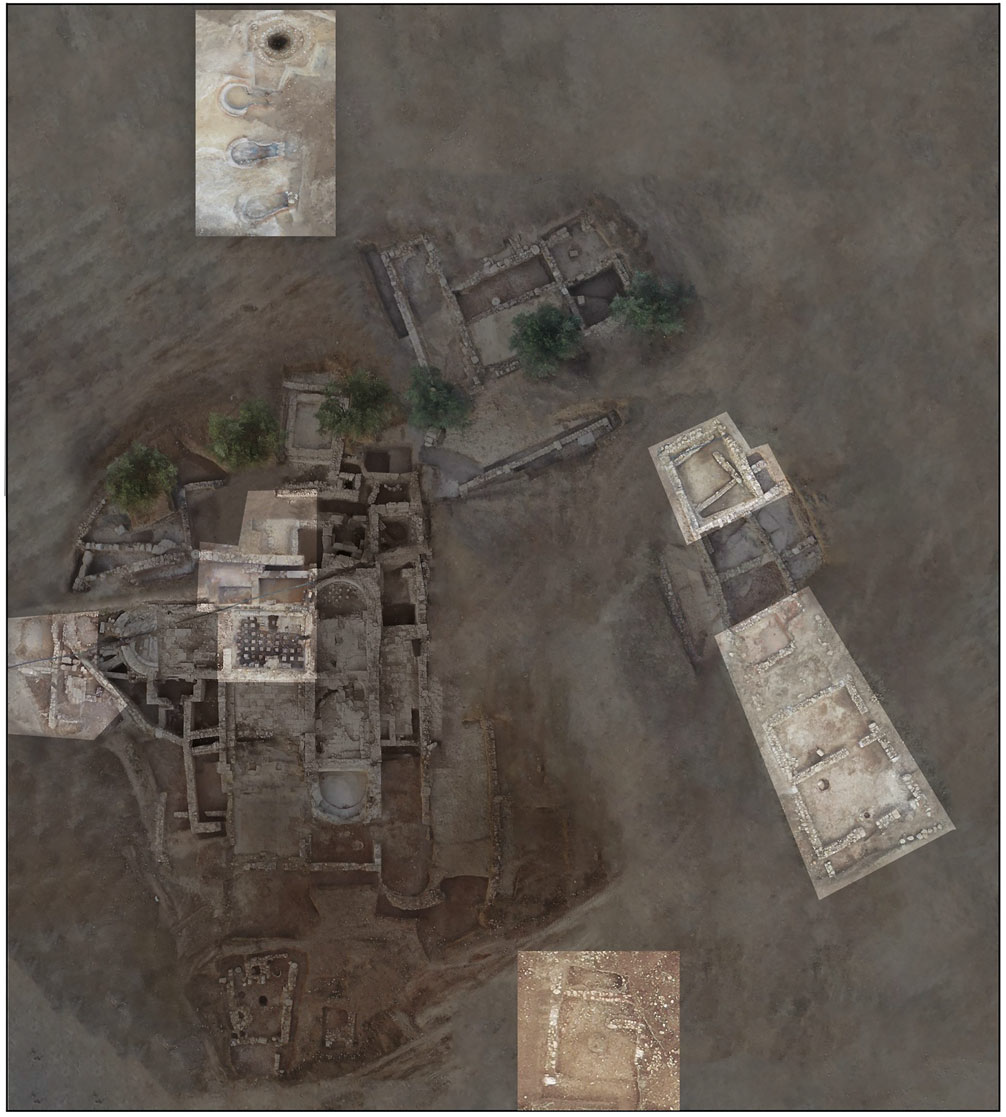

Athena Tsingarida and Didier Viviers (Université libre de Bruxelles) report on the first season of the new five-year Itanos campaign (2021–2025) (ID18152), under the auspices of the Belgian School of Archaeology at Athens (Viviers and Tsingarida Reference Viviers and Tsingarida2021). In 2021, two sectors were excavated. These point to an occupation going back to at least the seventh century BC, and to a significant reorganizational phase, subsequent to the destruction of the Archaic complex dated to the first half of the fifth century BC. A large slab and parts of a destroyed wall on the west side (Sector 14) may belong to the phase predating the construction of the Archaic complex. A Cretan aryballos dating to the seventh century BC was found under a levelling fill that covered these structures, along with a number of round stones north and west of the slab (Figs 3.63–3.64 ). Two of these rounded stones, along with a layer of ashes, were placed directly on the rock, which appears to have been cut out specifically for this purpose. On the east side (Sector 13), a badly damaged Hellenistic retaining terrace wall was brought to light. Underneath this, a circulation level appears to have been built on a levelling fill covering a thick destruction layer. The latter comprised fragmentary mud bricks and ceramic material, dated chiefly to the Archaic period. It seems to be the case that these came from the destruction of the southern façade of the Archaic complex, the southeastern interior corner of which was uncovered. Zone Γ, located north of the Archaic funerary complex, was also partially investigated in 2021. It occupies an intermediary terrace on the slope of the hill (Fig. 3.65 ) and bears on its surface evidence of destroyed graves, as well as the top of a number of walls. Work at the site continues.

3.63. Itanos, necropolis – Zone E, Sector 14: Cretan aryballos, seventh century BC (inventory number ITA21.61515.01) deposited on the rock. © EBSA.

3.64. Cretan aryballos, seventh century BC, after restoration. © EBSA.

3.65. Itanos, necropolis – Zone Γ. © EBSA.

Amanda Kelly (University College Dublin) reports on a second season of field inspection of the Aqueducts of the Greater Iraklio Area (ID18034, ID8142). The biggest discovery of the 2021 fieldwork was an in situ Roman-type stone pipeline at Karydaki (the main spring source of the Venetian aqueduct). The discovery of the Roman-type stone pipeline at Karydaki (Figs 3.66–3.67 ) constitutes a unique find in Crete and perhaps even in Greece. While fallen stone pipes have previously been identified on the east side of the Venetian bridge at Karydaki, the in situ stone pipeline is a new discovery. While Roman in terms of typology, these pipes are reused in this pipeline in the Venetian period (Kelly Reference Kelly2022). The supporting wall carried at least 19 in situ stone pipes (11 complete and at least another eight damaged in situ pipes) with at least another eight stone pipes lying on the ground below. This constitutes a more impressive number of in situ stone pipes than in any ancient stone pipeline. Similar stone pipelines from Asia Minor (modern Turkey) have largely been regarded as Roman in date, so this type of pipeline was a surprising find at the start of the walking study of a known Venetian aqueduct.

3.66. Karydaki Bridge, north face (photo facing southeast). © IIHSA (photo: A. Kelly).

3.67. Karydaki Bridge deck (photo facing east towards stone pipeline). © IIHSA (photo: A. Kelly).

At Gortyn (https://www.scuoladiatene.it/component/k2/nsa-ia-notizie-degli-scavi-della-scuola-archeologica-italiana-di-atene-2022-2.html), the investigation in the Byzantine Quarter, co-directed by Enrico Zanini and Elisabetta Giorgi (University of Siena), now also involves the area surrounding the ancient temple, where the 2019 excavations revealed an unsuspected continuity of use up to the seventh century AD (Fig. 3.68 ). This discovery has prompted a radical rethinking of the traditional interpretation, which linked the abandonment of the temple to an earthquake in 365 AD. In 2022 the excavation team reviewed the sparse documentation of the old excavation, cleaned up the walls and the bottom of the ‘crater’ left by previous interventions, and worked on a virtual reconstruction of the Late Antique walls, as well as recovering some of the chronologically-later finds that may have been discarded in previous excavations. This research, undertaken via a synergy between the University of Padua and the SAIA, promises to build a new narrative of Gortyn’s life in the early Byzantine period.

3.68. Drone photo of the area outside the Pythion at Gortyn, with traces of the late antique walls that were demolished in the 19th-century excavation. © SAIA.