The open-air stratified site of Kamyana Mohyla I was discovered by V.M. Danilenko in the 1930s. It is situated in front of a natural sandstone mound (Kamyana Mohyla, Figure 1), where numerous engravings and figurines have been recovered, mostly dating to the Metal Ages (Mykhailov Reference Mykhailov2005). The site has been excavated by a joint Swiss-Ukrainian expedition since 2011. The excavation revealed a long sequence over 4.2m deep, and the lower part comprises several Mesolithic habitations. The new finds described here come from this period, and consist of two zoomorphic sandstones, both intentionally shaped in order to resemble snake heads. They are a notable addition to the inventory of otherwise rare non-utilitarian objects of this age.

Figure 1. Kamyana Mohyla I (arrow) and the Kamyana Mohyla stone mound, viewed from the south (aerial photograph by S. Radchenko).

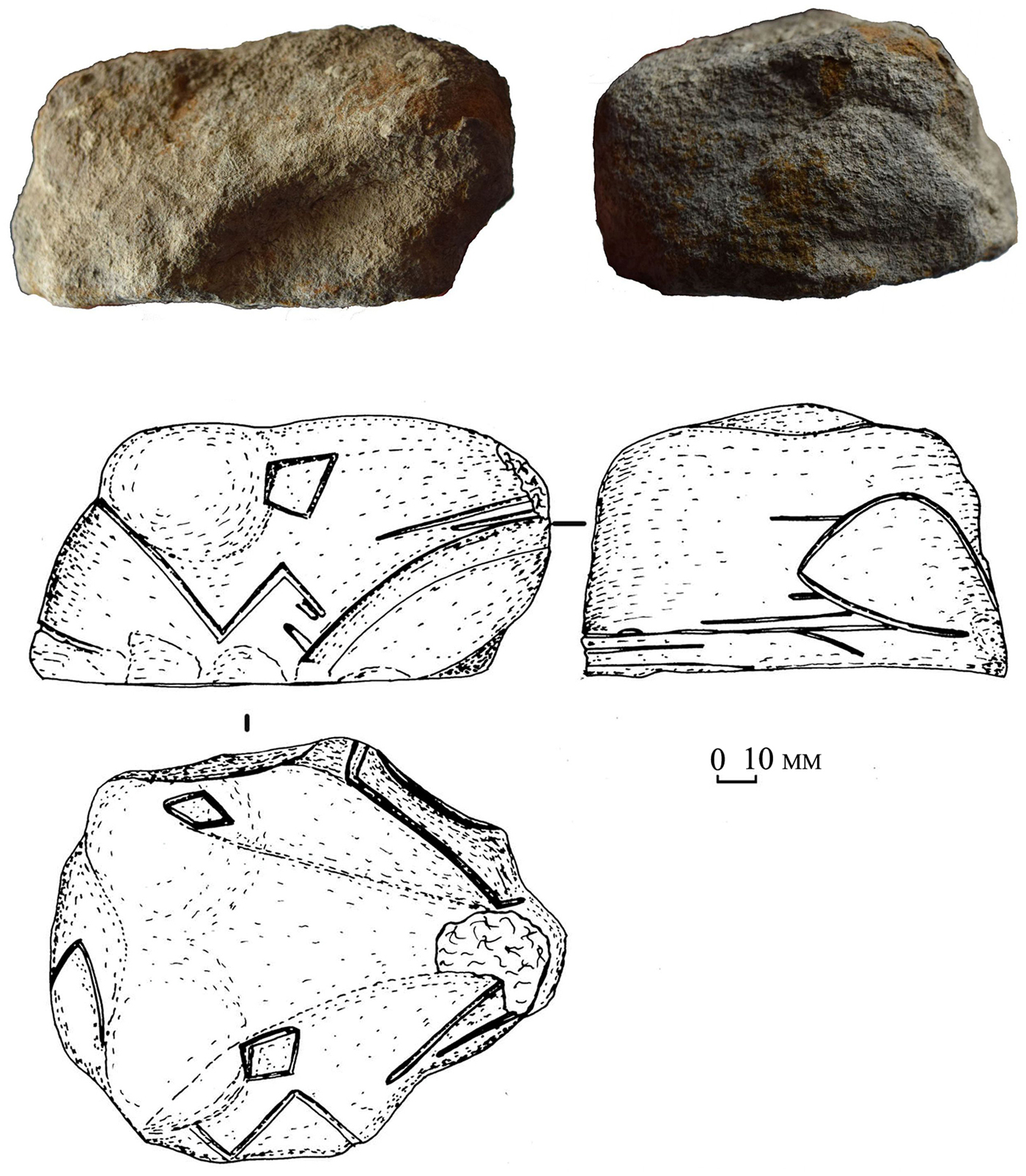

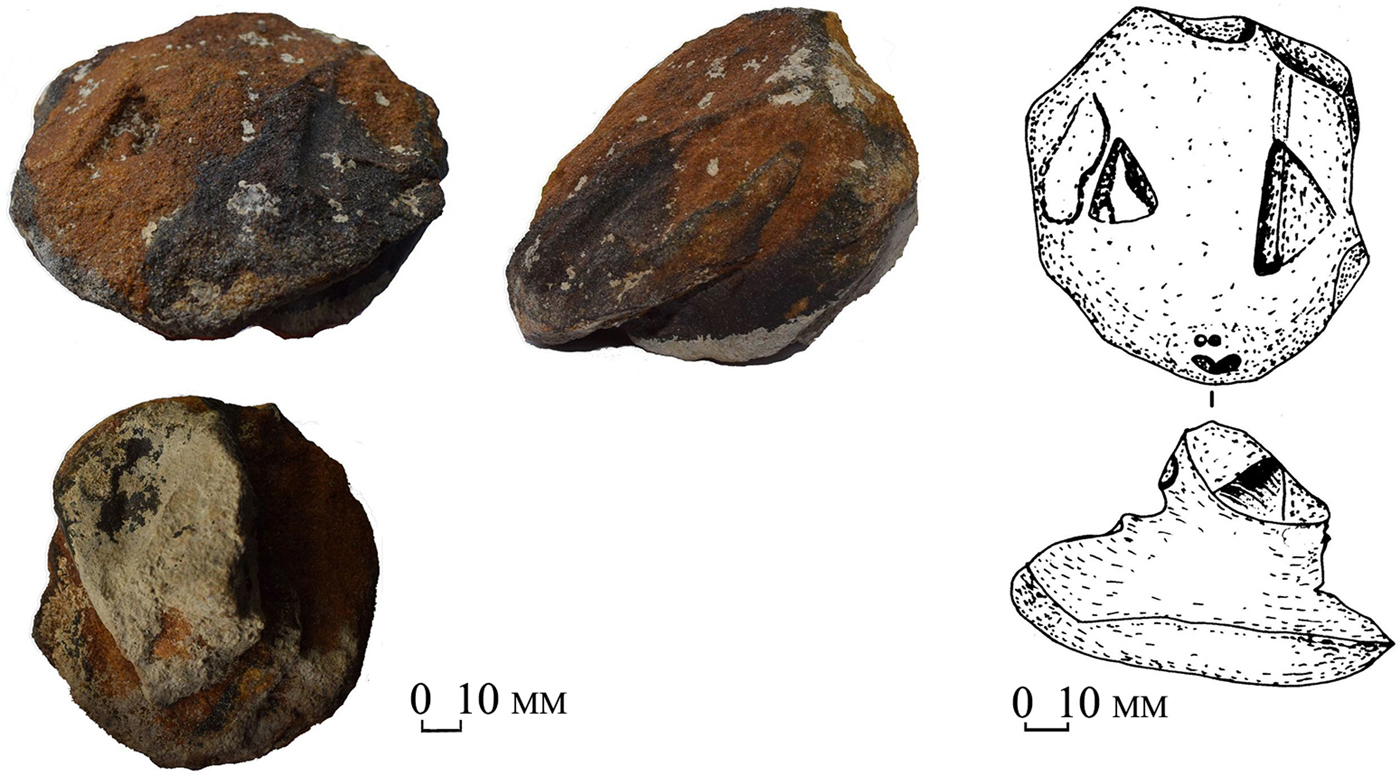

The ‘older’ figurine (Figure 2) was found in a Mesolithic cultural layer alongside an open fireplace, heaps of shells and occasional flint tools. The hearth provided two somewhat divergent radiocarbon dates: 8379±160 and 7550±107 cal BC, while the paucity of lithic finds precludes precise dating on the basis of material culture. The ‘younger’ figurine (Figure 3) came from another Mesolithic stratigraphic unit that contained a fireplace, which was radiocarbon-dated to 7424±46 cal BC. The zoomorphic stone was accompanied by four bone points and a lithic assemblage that included some ‘Kukrek inserts’ and an obliquely truncated bladelet (oblique point). These have close parallels with the local Mesolithic Kukrek technocomplex (Telegin Reference Telegin1982).

Figure 2. ‘Older’ figurine (figure by N. Kotova).

Figure 3. ‘Younger’ figurine (figure by N. Kotova).

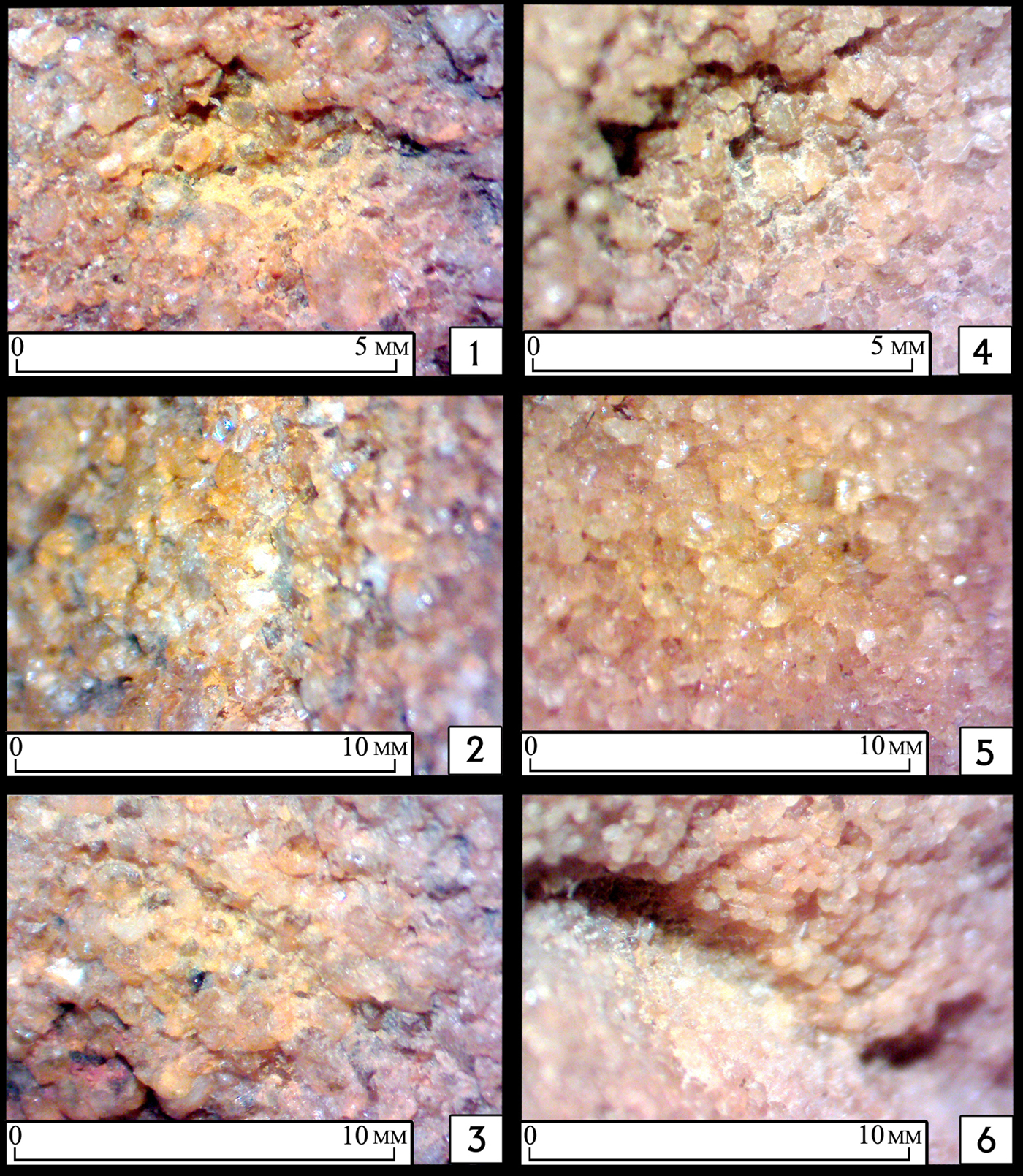

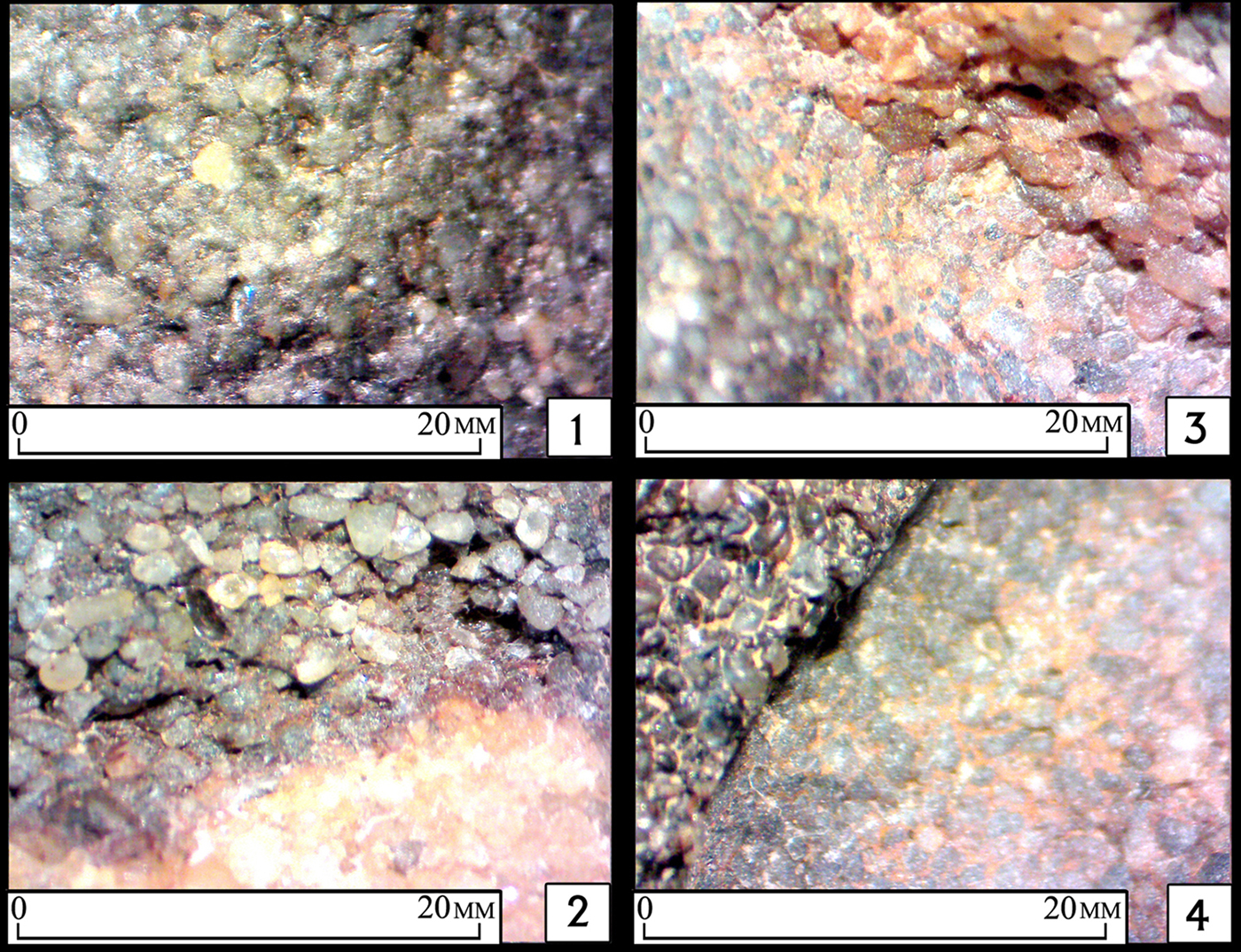

The figurines were examined under stereoscopic microscope (Optika SZM-45). Magnifying by a factor of 20 allows us to identify damage to single sandstone grains. These were compared to marks made by a flint tool on a sandstone block taken from the site. The examination reveals three ways of shaping the objects—striking, scratching and scraping (Figure 4). There are also some signs of water erosion on the younger figurine (Figure 5.1). Almost all of the surfaces received treatment, forming eyes, a ‘neck’, a mouse and some zig-zag patterns (Figures 4–5).

Figure 4. Microscopic examination of the ‘older’ figurine in comparison with experimental marks: 1–3) experimental marks; 4–6) traces on the figurine; 1 & 4) strikes with the flint cutter; 2 & 5) scratches; 3 & 6) traces of scraping (figure by S. Radchenko).

Figure 5. Microscopic examination of the ‘younger’ figurine: 1) traces of water erosion; 2) traces of scraping near the ‘neck’; 3) traces of strikes on the nose; 4) traces of scraping on the left eye (figure by S. Radchenko).

The older figurine measures 130 × 68mm. The stone has a subtriangular shape with a flat lower part. Two rhombic eyes were carved on the upper surface alongside two knobs. A wide long line represents a mouth. Several narrow lines and depressions are carved around the mouth, along with a zig-zag line on the left side of the head, continuing on the rear side with a triangle. The stone was damaged on the ‘nose’ during excavation. The most recent stone sculpture has a flattened shape with a clear ‘neck’. It measures 85 × 58mm. Two triangular eyes, a mouth in the shape of a butterfly and two points as a nose were carved on it. The closest comparator for the new finds comes from Kamyana Mohyla itself, where a fish-like stone was found out of stratigraphic context (Figure 6). Zig-zags were incised on bone points coming from the sites of Sursky I and Kizlevy V, and both zig-zags and rhomboids are found on bracelets from the cemetery of Vasylivka II. All these sites are slightly later in date than the Middle Mesolithic layer at Kamyana Mohyla I, and are considered to relate to the pottery-bearing Surska culture (Kotova Reference Kotova2003).

Figure 6. Fish-like stone from the Kamyana Mohyla mound (image courtesy of B. Mykhailov).

Serpent-like motifs are well known in Stone Age art outside Ukraine. These are mostly realised in softer materials (wood and antler) rather than stone. Ophidian images are present on the antler and bone tools of the Scandinavian and Baltic Mesolithic (Mundkur Reference Mundkur1983). Zig-zags were applied for the decoration of famous stone sculptures from Lepenski Vir (Srejović Reference Srejović1972), while zoomorphic stone figurines from the north Azov Sea region also provide parallels. Alternatively, the schematic realisation of images and decorative patterns on the Kamyana Mohyla examples connects them to another category of Mesolithic portable art—pebble-tokens with incised ornaments. The latter are known from many Mesolithic contexts from Britain (Milner et al. Reference Milner2016) up to the Ural Mountains (Zhilin Reference Zhilin2015). The Kamyana Mohyla ‘snakeheads’ may represent a variety of these tokens, and thus a next step towards 3D sculptures, as the support was shaped into a certain zoomorphic (ophidian) image.

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to Larisa Spitsyna, who passed away in the summer of 2018. The fieldwork on Kamyana Mohyla I was supported by the SNF SCOPES grant (Project IZ73Z0_152732).