In 1960, Robert Braidwood discovered, by chance, an Acheulean biface at Gakia, Kermanshah Province, in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran (Braidwood Reference Braidwood1960). Since then, only around ten Lower Palaeolithic sites have been identified on the Iranian Plateau, most of which are open-air sites (see Biglari & Shidrang Reference Biglari and Shidrang2006). Despite growing interest in the Palaeolithic of Iran over the past decade, studies generally continue to focus on particular sites and are largely concerned with the technology and typology of raw materials. A major problem for studies of the Lower Palaeolithic, in particular, is the rarity of cave sites, making it very difficult to study the behaviour of the early hominids through excavation. This paper reports the discovery of an Acheulean biface during a survey of the Deh Luran Plain to the south of the plateau, adding to the picture of human dispersal during the Pleistocene.

During the 1960s, Frank Hole and his team conducted a number of extensive surveys of the Deh Luran Plain, including excavations at Ali Kosh, Choqa Sefid, Faroukh Abad and Sabz (Hole et al. Reference Hole, Flannery and Neely1969; Wright Reference Wright1981). In addition, James Neely and Henry Wright conducted a survey of ancient irrigation and canal systems, identifying around 330 artefacts, including material from a Palaeolithic site (Neely Reference Neely and Hole1969). According to Neely, 96 stone artefacts were collected from an open-air site at Ain Girzan, including some with Bradostian features of the Zagros region (Neely & Wright Reference Neely and Wright1994: 163), although no photographs or drawings have been published to date.

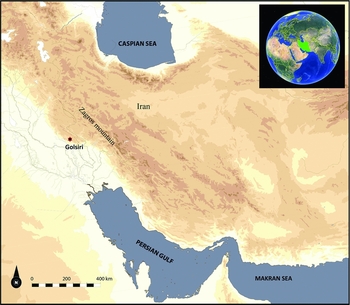

The archaeological significance of the Deh Luran Plain lies in its strategic location between Mesopotamia and the Susiana Plain to the south, and the Central Zagros Mountains to the north (Figure 1). The plain sits between 100 and 300m asl, and is situated between the Mehmeh and Dawairij Rivers. In 2016, archaeological survey in this region was undertaken in advance of new irrigation and drainage projects (Zeynivand Reference Zeynivand2016). During this work, a number of sites, from the Middle through to the Upper Palaeolithic, have been identified and studied (Figure 2). These sites are all located on the margins of the plain and on outcrops of the Bakhtiari Formation, providing abundant raw materials for lithic industries (Figure 3). A preference for similar site locations is also documented in adjacent regions such as the Karkheh Basin to the east (Bahramiyan & Ahmadzadeh Shouhani Reference Bahramiyan and Ahmadzadeh Shouhani2016) and the Mehran Plain to the north-west (Darabi et al. Reference Darabi, Javanmardzadeh, Beshkani and Jami-Alahmadi2012). One of the major discoveries during the survey of the Deh Luran Plain was an Acheulean biface, found on the northern side of Golsiri village, 8km north-west of the city of Deh Luran (Figure 4); the Mehmeh River, rising in the Kabir Kuh to the north, flows 3km to the west of the site. The biface is made of chert, 23cm long, 13cm wide and 6cm thick, and weighs 1.705kg (Figure 5); a number of chips are probably due to later usage or subsequent damage.

Figure 1. The location of the Golsiri site on the edge of the Central Zagros Mountains, Iran.

Figure 2. Some of the artefacts collected during the 2016 Deh Luran survey.

Figure 3. The availability of raw materials in Bakhtiari Formation.

Figure 4. The landscape of the northern Deh Luran Plain and the findspot of the biface.

Figure 5. The Acheulean biface discovered at Golsiri.

Since its identification by Neely, Palaeolithic studies of the Deh Luran Plain have focused on the site at Ain Girzan. Neely's survey, however, omitted the north-western and western edges of the plain, and it is precisely in these areas that recent survey work has identified open-air Palaeolithic sites on the Bakhtiari Formation. These include Middle and Upper Palaeolithic sites and an Acheulean biface. In relation to the latter, the site of Amar Merdeg, 100km to the north-west of Golsiri, has produced a collection of Lower Palaeolithic artefacts including a hand axe (Biglari et al. Reference Biglari, Nokandeh and Heydari2000). These sites are located in a natural corridor connecting the Levant with South and Central Asia, and contribute to growing knowledge of human dispersal through this region during the Pleistocene (e.g. Petraglia et al. Reference Petraglia, Drake, Alsharekh, Petraglia and Rose2009; Heydari Guran Reference Heydari Guran, Fahimi and Alizadeh2012; Vahdati Nasab et al. Reference Vahdati Nasab, Clark and Torkamandi2013).

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the Iranian Center for Archeological Research, and to Siamak Sarlak especially, for issuing permission to survey and for valuable collaboration.