Article contents

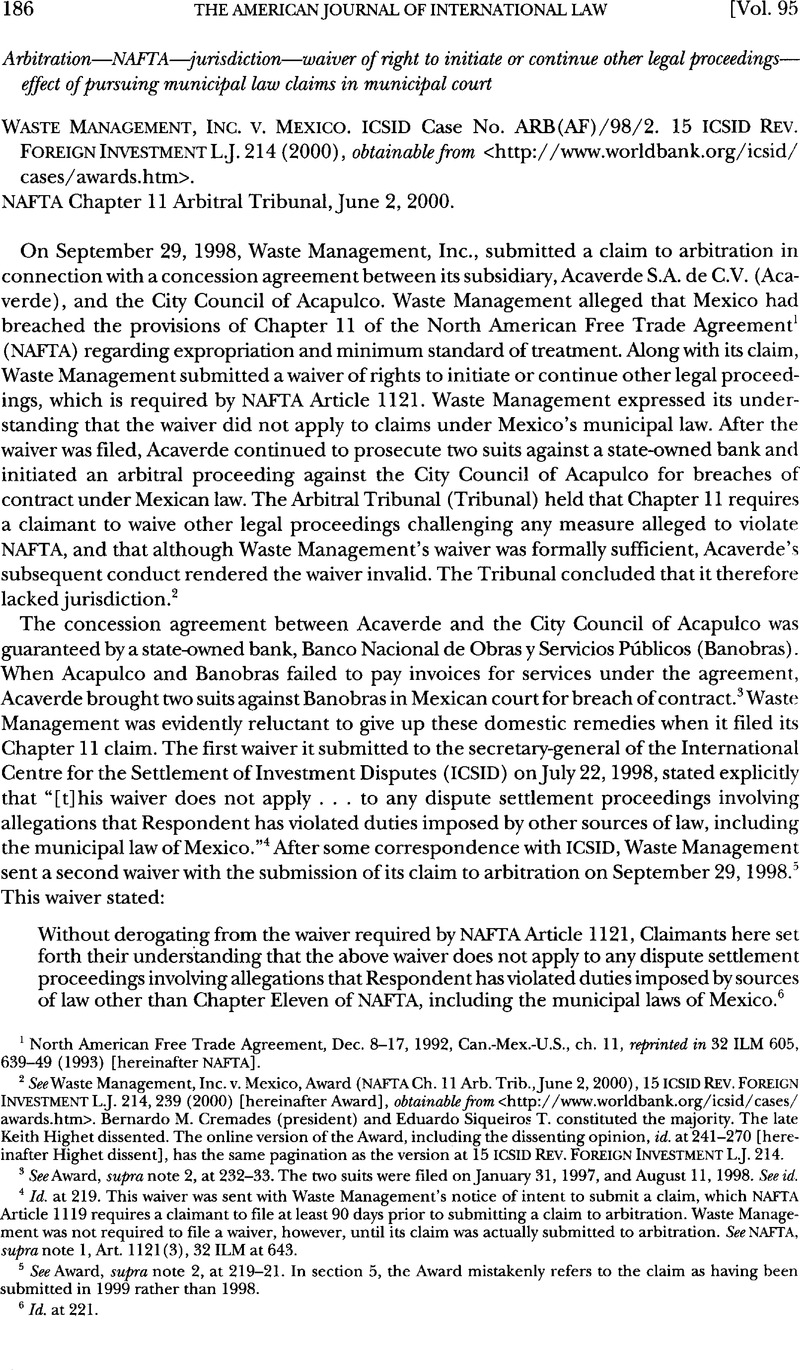

Waste Management, Inc. v. Mexico

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- International Decisions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2001

References

1 North American Free Trade Agreement, Dec. 8-17, 1992, Can.-Mex.-U.S., ch. 11, reprinted in 32 ILM 605, 639-49 (1993) [hereinafter NAFTA].

2 See Waste Management, Inc. v. Mexico, Award (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib., June 2, 2000), 15 ICSID Rev. Foreign Investment L. J. 214,239 (2000) [hereinafter Award], obtainable from <http://www.worldbank.org/icsid/cases/awards.htm> Bernardo M. Cremades (president) and Eduardo Siqueiros T. constituted the majority. The late Keith Highet dissented. The online version of the Award, including the dissenting opinion, id. at 241-270 [hereinafter Highet dissent], has the same pagination as the version at 15 ICSID Rev. Foreign Investment L.J. 214.

3 See Award, supra note 2, at 232-33. The two suits were filed on January 31, 1997, and August 11, 1998. See id,

4 Id. at 219. This waiver was sent with Waste Management’s notice of intent to submit a claim, which NAFTA Article 1119 requires a claimant to file at least 90 days prior to submitting a claim to arbitration. Waste Management was not required to file a waiver, however, until its claim was actually submitted to arbitration. See NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1121 (3), 32 ILM at 643.

5 See Award, supra note 2, at 219-21. In section 5, the Award mistakenly refers to the claim as having been submitted in 1999 rather than 1998.

6 Id. at 221.

7 See id. at 232-33. Acaverde’s suits against Banobras were dismissed in January 1999, and its appeals were unsuccessful. Acaverde abandoned its arbitration against Acapulco on July 7, 1999. Id.

8 NAFTA Article 1121(1), entitled “Conditions Precedent to Submission of a Claim to Arbitration,” provides in relevant part:

A disputing investor may submit a claim under Article 1116 to arbitration only if:... (b) the investor and, where the claim is for loss or damage to an interest in an enterprise of another Party that is a juridical person mat the investor owns or controls directly or indirectly, the enterprise, waive their right to initiate or continue before any administrative tribunal or court under the law of any Party, or other dispute settlement procedures, any proceedings with respect to the measure of the disputing Party that is alleged to be a breach referred to in Article 1116, except for proceedings for injunctive, declaratory or other extraordinary relief, not involving the payment of damages, before an administrative tribunal or court under the law of the disputing Party.

Article 1121(2) requires the same waiver for claims under Article 1117 on behalf of an enterprise that the investor owns or controls.

9 NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1122 (1), 32 ILM at 644.

10 Award, supra note 2, at 228; see id. at 227-28. The Arbitral Tribunal (Tribunal) also noted that Article 1121 provides for the submission of a claim “only if” the proper waiver is filed. See id. at 227.

11 Id. at 229.

12 NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1121(3), 32 ILM at 643.

13 Award, supra note 2, at 230; see id. at 230-31. Consistent with this position, the Tribunal also concluded that “submission of the waiver must take place in conjunction with” the submission of the claim to arbitration. Id. at 229.

14 See id. at 231. This argument suggests that the reason Mexico did not use the waiver to seek dismissal of Acaverde’s two suits against Banobras was that the waiver, absent the requisite formalities, would not have been deemed sufficient in a Mexican court.

15 Id. at 227.

16 Id. at 231-32.

17 See id. at 233-38. The Tribunal assumed that the purpose of requiring such a waiver was to avoid the possibility that a claimant might recover twice for the same damages—once in a domestic forum and once before a Chapter 11 tribunal. See id. at 235-36.

18 Id. at 236.

19 Id. at 239.

20 See Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 245-46; NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 201, 32 ILM at 298 (“measure includes any law, regulation, procedure, requirement or practice”).

21 Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 246. In support of his narrow reading of Article 1121, Highet also observed that it requires a waiver not of all proceedings that somehow related to the measure alleged to breach NAFTA, but only of proceedings “with respect to” such a measure. “[A]s a legal matter, this means that the proceeding must primarily concern, or be addressed to, that measure.” Id. at 252.

22 Id. at 260.

23 Id. at 258. See NAFTA, supra note 1, Annex 1120.1, 32 ILM at 648 (“an investor of another Party may not allege that Mexico has breached an obligation under [NAFTA] both in an arbitration under this Section and in proceedings before a Mexican court or administrative tribunal”).

24 Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 260.

25 See id. at 247.

26 Id. at 253.

27 Id. at 256.

28 Id. Highet also faulted the Tribunal for looking to Waste Management’s postwaiver litigation to eviscerate the waiver while ignoring its subsequent abandonment of those suits. See id. at 263 (“[E]ven if the substance of the Article 1121 waiver had been—as the majority of the Tribunal believes—eviscerated in 1998 or 1999, why was that substance not restored... later in 1999 or in January 2000?”). Acaverde abandoned its litigation against Banobras, however, only after exhausting its appeals. See Award, supra note 2, at 233. Acaverde did abandon the domestic arbitration against the City Council of Acapulco in July 1999, see id., although the arbitral tribunal never formally declared the proceeding closed, see id. at 238.

29 Ethyl Corp. v. Canada, Jurisdiction, Award (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib., June 24, 1999), reprinted in 38ILM 708 (1999) [hereinafter Ethyl arbitration]; see Swan, Alan C., Case Report: Ethyl Corporation v. Canada, 94 AJIL 159 (2000)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

30 See Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 264-68.

31 See id. at 267.

32 For a discussion of other questions concerning this relationship, see William S. Dodge, National Courts and International Arbitration: Exhaustion of Remedies and Res Judicata Under Chapter Eleven of NAFTA, 23 Hastings Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 357 (2000).

33 Article 1121 expressly permits a claimant to seek damages from a Chapter 11 tribunal and simultaneously or subsequently to seek declaratory or injunctive relief in domestic court—relief that Chapter 11 tribunals are not capable of granting. See NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1135, 32 ILM at 646.

34 Id., Art. 1121(1), (2), 32 ILM at 643 (emphasis added).

35 See Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 258.

36 See North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act, 19 U.S.C. §3312(c) (2) (1994) (“No person other than the United States .. . may challenge, in any action brought under any provision of law, any action or inaction by any department, agency, or other instrumentality of the United States, any State, or any political subdivision of a State on the ground that such action or inaction is inconsistent with [NAFTA] . . . .”); North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act, R.S.C., ch. 44, §6(2) (1993) (Can.) (“Subject to Section B of Chapter Eleven of the Agreement, no person has any cause of action and no proceeding of any kind shall be taken, without the consent of the Attorney General of Canada, to enforce or determine any right or obligation that is claimed or arises solely under or by virtue of the Agreement”).

37 See Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 260.

38 Indeed, I have argued that Article 1121 is structured to encourage investors to pursue local remedies before resorting to Chapter 11. See Dodge, supra note 32, at 381—83. Of course, an investor who does pursue its domestic remedies before turning to Chapter 11 runs the risk that the Chapter 11 tribunal will treat the domestic decision as res judicata. See, e.g., Azinian v. Mexico, Merits, Award (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib., Nov. 1, 1999), reprinted in 39 ILM 537 (2000), obtainable from <http://www.worldbank.org/icsid/cases/awards.htm>. For further discussion of res judicata in the context of Chapter 11, see Dodge, supra note 32, at 376-83.

39 NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1121 (3), 32 ILM at 643.

40 See supra note 28 and accompanying text.

41 See NAFTA, supra note 1, Arts. 1116(2), 1117(2).

42 U.S. Waste Control Firm Refiles Case Under NAFTA Investor-State Provisions, 17 Int’l Trade Rep. 1528 (Oct 5, 2000).

43 Ethyl arbitration, supra note 29.

44 Pope & Talbot, Inc. v. Canada, Award in Relation to Preliminary Motion by Government of Canada to Strike Paragraphs 34 and 103 of the Statement of Claim from the Record [the “Harmac Motion”] (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib., Feb. 24, 2000), 23 Hastings Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 447 (2000) [hereinafter Pope & Talbot Harmac motion]. As of this writing, there has not been a final award in the Pope & Talbot case. There has been a series of interim awards, however, dealing with such issues as the scope of Chapter 11, the waiver requirement, performance requirements, expropriation, and the submission of new claims. Four of these awards (including the award on the Harmac motion) are reprinted in 23 Hastings Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. at 431-93. The final award will be reported in a subsequent issue of the Journal

45 Award, supra note 2, at 228.

46 Id. at 230.

47 Ethyl arbitration, supra note 29, 38 ILM at 723.

48 Award, supra note 2, at 229.

49 See Ethyl arbitration, supra note 29, 38 ILM at 729 (allowing waiver to be submitted with statement of claim filed nearly six months after submission of the claim to arbitration); Pope & Talbot Harmac motion, supra note 44, at 452 (allowing waiver submitted nearly two years after the submission of a claim to have “retroactive effect”).

50 Award, supra note 2, at 229.

51 See Ethyl arbitration, supra note 29, 38 ILM at 729 (Article 1121 “seem[s] designed to memorialize expressis verbis what is normally the case in any event, namely, that the initiation of arbitration constitutes consent to arbitration by the initiator, whereby access to any court or other dispute settlement mechanism is precluded”); Pope & Talbot Harmac motion, supra note 44, at 451 (“the initiation of arbitral proceedings may be taken as a constructive waiver of the right to initiate other proceedings”).

52 See Ethyl arbitration, supra note 29, 38 ILM at 728-29 (“It is not doubted that today Claimant could resubmit the very claim advanced here Clearly a dismissal of the claim at this juncture would disserve, rather than serve, the object and purpose of NAFTA.”).

53 See supra notes 41-42 and accompanying text.

54 NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1136, 32 ILM at 646. The provision seems to be drawn from Article 59 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which is based on Article 59 of the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice. The Permanent Court interpreted Article 59 to reject a system of binding precedent. See Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia (Ger. v. Pol.), 1926 PCIJ (ser. A) No. 7, at 19 (May 25) (“The object of [Article 59] is simply to prevent legal principles accepted by the Court in a particular case from being binding on other States in other disputes.”).

55 Cf. Highet dissent, supra note 2, at 241 (noting that “the Award will be an important guidance to future potential NAFTA claimants”).

56 See W. Michael Reisman, Systems of Control in International Adjudication and Arbitration 8-9 (1992) (distinguishing between control and appeal).

57 See NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1131(2), 32 ILM at 645. Another system of control exists in the provisions for review by a court in the country where the award was rendered in a proceeding for annulment, see id. Art. 1136 (3), 32 ILM at 646, and by a court in the country where enforcement is sought under the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (New York Convention), June 10,1958,330 UNTS 38, or Inter- American Convention on International Commercial Arbitration (Inter-American Convention) J a n . 30,1975,14 ILM 336 (1975). See NAFTA, supra note 1, Art. 1136(6), 32 ILM at 646. For discussion of the New York Convention as a system of control, see Reisman, supra note 56, at 109-20.

Even where an important domestic law or practice is found to violate NAFTA, a state should have no right to resist enforcement of a Chapter 11 award on public policy grounds under Article 5(2) (b) of the New York Convention or Article 5(2) (b) of the Inter-American Convention. The NAFTA parties have agreed to subject their domestic law to the disciplines of Chapter 11, which should preclude the parties from complaining that an award applying those constraints contravenes their public policy.

58 See, e.g., Ethyl arbitration, supra note 29,38ILM at 711 (noting Ethyl’s claim that Canada’s MMT Act violated Chapter 11 provisions on national treatment, performance requirements, and expropriation); Metalclad Corp. v. Mexico, Merits, Award (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib., Aug. 30,2000) <http://www.pearcelaw.com/metalclad.html> (holding that denial of claimant’s right to operate a landfill on environmental grounds was a denial of fair and equitable treatment and an expropriation); Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim (July 2, 1999), Methanex Corp. v. United States (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib.) <http://www.methanex.com/investorcentre/mtbe/noticeofintentpdf> (alleging that California’s decision to ban the gasoline additive MTBE is an expropriation and a denial of fair and equitable treatment). The Metalclad award will be reported in a subsequent issue of the Journal 59 See Notice of Claim (Oct. 30, 1998), Loewen Group, Inc. v. United States (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib.) (on file with author) (claiming that punitive damages judgment constitutes inter alia an expropriation and a denial of justice).

59 See Notice of Claim (Oct. 30,1998), Loewen Group, Inc. v. United States (NAFTA Ch. 11 Arb. Trib.) (on file with author) (claiming that punitive damages judgment constitutes inter alia an expropriation and a denial of justice)

- 4

- Cited by