Introduction

Prospective care-givers and aged care in a collectivist culture

In China, the estimated number of people aged 60 and above is expected to increase from 230 million to 490 million between 2019 and 2050. Similarly, for those aged 80 years and above, the number is expected to rise from 25 million to 121 million by 2050 (United Nations, 2019). The ageing population continues to grow globally with diminution in family size (Xiuxiang et al., Reference Xiuxiang, Zhang and Hockley2020) and those who live to old age are likely to experience a range of chronic health conditions (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Quan, Fu, Zhao, Li, Wei, Tang, Qin, Wang, Qiao, Shi, Wang, Du, Zhang, Zhang, Luo, Qu, Zhou, Gauthier and Jia2019). There are concerns about how traditional family-based care-giving systems will cope with the rising demands for care for older people (Tang, Reference Tang2021). Given this context, in this study we explored the perspectives of Chinese students in England on intergenerational ties and filial obligations. Existing literature has focused on the care-giving burden amongst Chinese family care-givers (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Lou2015; Du et al., Reference Du, Shao, Jin, Qian, Xu and Lu2017), however, individual subjective experiences have not been explored in depth. In addition, current research have not yet addressed areas relating to transnational students' appraisals of their future care-giving roles and expectations. Therefore, this current paper seeks to address the opportunities and challenges that Chinese transnational students could confront within the context of supporting their parents in the later stage of their life, which makes a novel contribution to knowledge as it responds to calls in the literature for a pre-emptive role of research on ageing (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Scheibye-Knudsen, Jahn, Li, Ling, Guo, Zhu, Preedy, Lu, Bohr, Chan, Liu and Ng2015).

Filial piety, Xiao (孝), is the obligation of offspring to care for, support and meet the needs of their parents through showing respect and obedience, as well as providing emotional and financial assistance (Smith and Hung, Reference Smith and Hung2012). This shared virtue promotes a great sense of identity and family cohesiveness (Park and Chesla, Reference Park and Chesla2007), plays a significant role in shaping parent–child relationships and informs the pattern of older people's care (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Chen, Chang and Dong2014). Furthermore, the obligations of Xiao embody the responsibility of families to care for their older relatives, especially important given China's current lack of formal services for older people (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu, Tan, Li, Lou, Chen, Chen, Fletcher, Carrino, Hu, Zhang, Hu and Wang2021) and the major socio-demographic transition due to the One-Child Policy (OCP). These factors have implications for who will provide care for future generations of older people. In addition, individuals within Chinese society are socialised to meet family and friends' needs ahead of their own, compared to countries where individuals are socialised to have the welfare state cater for those who need support. Family members are, therefore, at the heart of care provision.

Understanding future expectations around fulfilling filial piety, Xiao, is especially pertinent with the increase in the numbers of women in employment (Tang, Reference Tang2021), rapid urbanisation (Li et al., Reference Li, Long, Essex, Sui and Gao2012; Marvalovà, Reference Marvalovà2018) and the consequences of the OCP. There are certain societal expectations for women, such as getting married by 30 (Zhang and Xu, Reference Zhang and Xu2020). Also, within the traditional patrilineal society of China, sons are expected to live with their parents and provide them with financial support. These traditional expectations are still present in modern China amongst young men (Warmenhoven et al., Reference Warmenhoven, Hoebink and Janssens2018). Despite China's economic advancement and legislations in place to aid gender equality, there remains a severe underrepresentation of women in management and leadership roles, reducing female workforce representation and increasing wage gaps (Wang and Klugman, Reference Wang and Klugman2020). Alongside sons' obligations, unmarried daughters are expected to provide hands-on care, with daughters-in-law becoming primary care-givers in the absence of offspring (Tang, Reference Tang2021).

With the OCP giving rise to a large number of only-children amongst middle-class families (Tu and Xie, Reference Tu and Xie2020) and the dominance of private sectors driving China's economy, women tend to be limited in gaining career advancement (Wang and Klugman, Reference Wang and Klugman2020). This limitation might be the motive behind parents' heavy investment in their offspring's education to ensure that they stand a chance in a fiercely competitive labour market. In the context of the lingering patrilineality in China, one of the unanticipated consequences of the OCP is that gender equality appears to be taken seriously. As such, China is one of the highest suppliers of international students across the globe (Liu, Reference Liu2016). The number of Chinese students coming to the United Kingdom (UK) continues to grow significantly (Tu and Nehring, Reference Tu and Nehring2020), with a high proportion being female (Zhang and Xu, Reference Zhang and Xu2020). Zhang and Xu (Reference Zhang and Xu2020) showed that exposure to Western countries could be a powerful advantage to being competitive in the labour market in China, but due to stringent UK visa requirements (Tu and Nehring, Reference Tu and Nehring2020), the majority of Chinese immigrants studying in the UK return to China. However, this return would most likely come with expectations to support parents or extended family who invested heavily in them. The oversupply of transnational students and improved domestic higher education can make it difficult for overseas returnees, referred to as hǎi guī – 海归, to land desirable or high-paying jobs and they are sometimes referred to condescendingly as ‘seaweed’ (hǎi dài – 海带) or ‘work-waiting returnees’ (Liu, Reference Liu2016: 48). Given globalisation, exposure to alternative ideologies could alter individual thresholds of filial obligation and moderate the impact of cultural values on role appraisal (Kuo, Reference Kuo, Rabi, Steverson and Kuo2011). Thus, students' exposure to Western societies may lead to individuals internalising values around individual autonomy. In essence, there is a need to focus on understanding meanings associated with cultural values, especially in China, where filial obligation is pertinent to family care-giving. Furthermore, with a critical gap in social care (Zhu and Walker, Reference Zhu and Walker2018) and long-term care support (Du et al., Reference Du, Dong and Ji2021), prospective care-givers could be left to provide the necessary care for older relatives alone, which could be detrimental to their wellbeing.

Caring attitudes: willingness, preparedness and obligations

There is considerable research around obligation and willingness to care. In the UK, recent findings suggested that care-givers for people with dementia can feel obligated to fulfil the role, irrespective of their personal preference (Parveen et al., Reference Parveen, Fry, Oyebode, Morrison and Fortinsky2019). Becoming a care-giver may imply willingness to do so. However, the person may be providing care due to a sense of obligation or lack of alternatives (Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Clare and Woods2010). Further, Al-Janabi et al. (Reference Al-Janabi, Carmichael and Oyebode2018) found that having a sense of choice about taking on care-giving was strongly associated with care-givers' wellbeing, even in situations where there was also an obligation. Additionally, whether a care-giver felt well prepared for the role was associated with care-giver wellbeing (Shyu et al., Reference Shyu, Yang, Huang, Kuo, Chen and Hsu2010). In the absence of adequate support for family care-givers, psychological, financial and physiological stressors occur, resulting in care-giving burden (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Chen, Xue, Li and Zhang2019a). These stressors are associated with domiciliary care (Lin, Reference Lin2019), care-givers being isolated from social networks (X Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Clarke and Rhynas2019), nursing homes' long waiting lists (Tang, Reference Tang2021) and lack of support from primary health-care workers (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shao, Li, Liu, Xu and Du2018). Positive or negative care-giving experiences can proliferate in the care-giver's social environment and impact individuals who are not directly involved in care (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Aneshensel and Leblanc1997). As such, given the complexities around preparedness, willingness and obligation to care (Sherman, Reference Sherman2019), it is important in the current Chinese context to understand the influence of filial piety, Xiao, on caring for older people.

Study aims

To the best of our knowledge, very little is known about the perspectives and preparedness for future care roles of those highly educated and born during the OCP. This study therefore explores in-depth perceptions of Chinese students in England regarding their potential future care-giving obligations, including consideration of filial piety, Xiao. Findings are discussed, and implications are underscored based on the backdrop of the socio-cultural transitions against expectations of future care for older family members.

Methods

Research design

We adopted a focus group method using semi-structured topic guides, which aligned with our social constructivist philosophical position. Focus groups were specifically chosen to generate discussions and debates among participants. The study aimed to capture wide-ranging opinions around care-giving and produce an in-depth analysis of the account of small groups rather than a representative sample.

Recruitment and ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Humanities, Social and Health Sciences Research Ethics Panel, University of Bradford. Criteria for inclusion were that participants had to be aged 18 and above and from mainland China, with or without caring responsibilities. A convenience sample was recruited from current students at the University of Bradford. Students were invited via their university email accounts and WEChat (the main Chinese mainland social media platform). Students who responded to the invitations were invited to link the researchers to other potential participants. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic, OB and BZ met with all who expressed an interest to provide an information sheet in English and Mandarin and establish that they understood the study. Discussions were held about, for example, study objectives, confidentiality, data management and anonymity. Participants were given at least seven days after receiving the information sheet to think about participating and were informed that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. Informed consent and demographic information were obtained on the day of the focus group. OB paid close attention to participants' wellbeing during focus groups and offered to pause the recorder or stop the interview if anyone showed or expressed signs of distress or discomfort. Individual de-brief sessions were offered at the end of the focus groups but no participants opted for this support.

Twenty-four potential participants expressed interest. Four declined for reasons such as time constraints and one did not meet the nationality criteria. The total number of participants was therefore 19. We conducted three focus groups, with six to eight participants at each. Information about the participants is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Participants' demographics

Data collection

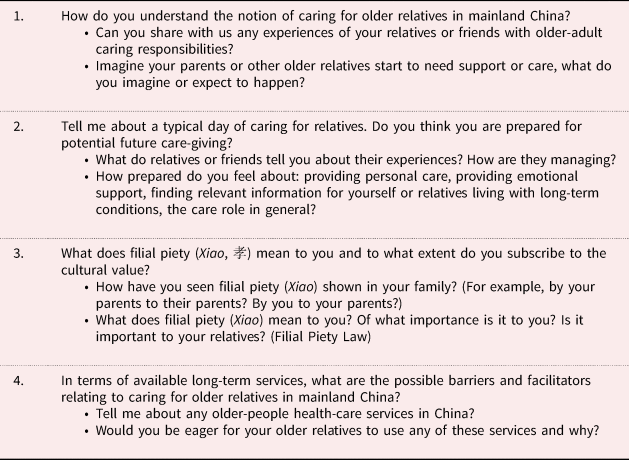

The topic guide was co-designed by the researchers based on existing literature on Chinese culture and care provision for older relatives. This was further informed by a visit to China, which included discussions with Chinese collaborators and students. Discussions with Chinese collaborators reinforced the knowledge garnered via our literature review (Bífárìn et al., Reference Bífárìn, Quinn, Breen, Wu, Ke, Yu and Oyebodein press). OB and BZ facilitated the groups. BZ, a research assistant from mainland China, translated and helped capture cultural nuances. Open-ended questions were asked by OB to probe what participants knew about the experiences of relatives or friends with caring responsibilities, participants' preparedness and future willingness to care for their parents, their personal understanding and enactment to date of filial piety, and their experience, knowledge and attitudes to long-term care services (see Table 2).

Table 2. Interview guide and some prompts

To enable participants to imagine possible future care-giving, some questions focused on potential future care needs, e.g. an older parent needing assistance with nursing care or the facilitation of medical appointments. The average duration was 100 minutes and discussions were audio-recorded. Participants often switched between English and Mandarin and BZ translated. The first focus group was observed by an experienced researcher CQ, who gave the facilitators feedback. To raise reflexivity and inform focus group conduct, the facilitators de-briefed together before and after each focus group. The audio-recordings were transcribed by OB, and BZ transcribed and translated the Mandarin passages. This allowed the researchers to check how well nuances had been captured in translation during the discussions.

Data analysis

Data analysis commenced after all data were collected and was carried out manually by four researchers (OB, JO, CQ, LB). OB has a mental health nursing background and could relate to the essentials of a collectivist society by virtue of his Nigerian upbringing. JO and CQ brought perspectives as clinical-academic psychologists and applied dementia researchers. LB brought a health-care service design and delivery perspective.

Data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) to yield contextualised understanding (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2014). The method creates an avenue to accumulate knowledge, identify literal, pragmatic, experiential and existential meanings (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013) relating to a specific phenomenon of interest, and conceptualises patterns of human behaviour, creating opportunities for unexpected themes to be identified (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). RTA afforded us the flexibility needed to capture semantic and latent meanings and enabled us to employ both descriptive and interpretative approaches to the data (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022). Consonant with RTA, researchers adopted both inductive and deductive approaches, as the process involved in identifying themes was not independent of researchers' knowledge and collective expertise on the object of interest (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Consequently, analysis was data and researcher driven. The process was guided by openness and reflection. All six iterative phases of RTA were followed: ‘familiarisation, coding-generation of preliminary themes, reviewing and developing themes, refining, defining and naming themes; and writing up’ (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021: 39).

Data familiarisation involved reading and re-reading transcripts individually. Then, each researcher generated initial codes to capture descriptive content of meaningful text segments and made memos of their interpretations. Codes were discussed to gain consensus, and memos were debated to raise researchers' reflexivity. Following descriptive coding, all codes were listed, and OB began the active process of grouping these into meaningful sub-themes and themes, assembling them into clusters according to shared or similar meanings (for three examples of the clusters, see Table 3).

Table 3. A sample of the analytic procedure showing connections from data segments to codes, sub-themes and theme

Emergent sub-themes and themes were discussed in the wider research team. Several iterations took place until consensus was reached on a set of themes and sub-themes, which appeared to best capture the content and meanings of data. These were reviewed by BZ, who considered the plausibility of the findings. Participants' quotes were used to ensure the results were grounded in the text and to illustrate the themes, which equally influenced the title of the themes.

Findings

Six themes were identified and encompassed under an overarching theme, namely Culture of Duty (see Figure 1). The prominence of family obligation and expectations within Chinese mainland society could leave future care-givers in a dilemma about balancing their personal needs with care responsibilities. Despite Xiao impressing various meanings on participants, the common thread discovered was that reciprocity strongly underpinned motivation for future care-giving. The overarching theme reflects the significant role of family within mainland Chinese society and equally shows the relational tensions therein.

Figure 1. Overview of theme.

The glue of the society

Most participants described Xiao as a cultural value which acted as the glue of society and family. It was seen as a virtue of reciprocity with karmic-like consequences. Xiao was seen as being transmitted by example, from one generation to the next. In the following excerpt, the participant suggests that if a good example is not set, a person might find themselves not cared for in turn by their own children:

Not all the people are good people. Some people are saying they cannot support their parents and relatives like the others do. If you don't take care of your parents, and when you get old your children will do the same. So, it is kind of rule to keep the society going well … in Chinese society, I think Xiao is basic for like family relationships at least, to keep it well. (P04)

By preceding this description of karma with the phrase ‘Not all the people are good people’, she highlights the moral value she attaches to acting virtuously in fulfilling Xiao, with those who could not support their parents being viewed negatively. Participants expressed a view that the power with which Xiao was imbued could lead to it sometimes being used as a threat by parents. In this example, the participant describes Xiao as a bond, a term that simultaneously implies both closeness and a chain or tie:

Xiao is that it is like a bond between parent and children. With this bond, it kind of determines the relationship between parent and children … Sometimes it can be a tool, which parent can use to threaten children. (P01)

The end of this quote from P01 conveys the view that Xiao can be weaponised by parents to make their children comply with their expectations of being cared for.

Overall, this theme reflects the crucial role Xiao plays within Chinese society. Participants' accounts suggested that Xiao would continue to act as a binding force for families and society whether through intrinsic values or as a manipulative tool. It was evident that Xiao still held great relevance for our participants and, most importantly, it underlined the significance of family in the wider culture.

Shared care

The general consensus among participants was that circumstances dictated the type of support provided by family members. Illustrated by the following excerpt, those deemed to have fewer responsibilities in their personal lives (e.g. those unemployed) provided the hands-on care and those in employment sometimes provided financial assistance:

My grandparents at my mom's side, they've got overall six children. If they split care; it is not a very big issue for everyone … And my older auntie's child has got a newborn. It means there's a double-care responsibility for her; taking care of older parents, and a newborn. It means the care responsibility for the older parents comes to my younger auntie. In this case, those who work will take less face-to-face care responsibility than unemployed (younger auntie meeting grandparents daily) but the employed children will sometimes support with finance. (P13)

When organising care and supporting older relatives, dividing responsibilities between siblings was feasible for past generations but with demographic changes in China, the majority of participants had no (or few) siblings and envisaged that future care responsibilities might be overwhelming:

Nowadays we have a lot of single child families. In the past people split the Xiao as multi-children families do, but for more single child families there will be more Xiao responsibilities’ (P19)

Referring to only-children whose parents might develop long-term health conditions, P09 subsequently expressed that such situations could be unbearable and inflict pain:

…determined by the health conditions of the elderly. For those who keep healthy till they die, their children could easily manage it with Xiao, but in opposite conditions, their children can be suffering in applying Xiao. (P09)

With awareness of the compounding pressures that only-children will face in caring alone for ageing parents with health conditions, participants raised concerns about the difficulty of balancing work and care:

A lot of young people, they go to work in big cities, could be very far from the hometown, where the parents are living. So, sometimes it is just impossible to manage when the parents get ill … they have to go to the hospital and children have work to do in a very far city. (P10)

In this quote, P10 reflects on how having to work far away from parents due to rapid urbanisation in China makes it practically impossible to attend to parents' health concerns in a timely manner. P07 was studying abroad when his mother took ill. In hindsight, he reflected on his difficulty with aligning the desire to prioritise personal ambitions with the significance of being present to accompany his parents at a time of need.

I'm the only child, sometimes it's a struggle to choose between your own life and your care for your parents. (P07)

This theme shows the significant role family members played in supporting one another as this was considered to be their duty and responsibility. Familial resources that were available to their parents' generation were not anticipated as an option for the younger generation who will inevitably be in the position of providing care alone. Consequently, where only-children might also live or work far away from parents, the difficulty of Xiao intensifies.

Social pressure

Several participants had witnessed how the importance given to obedience can lead to society overlooking willingness to provide care in the way that tradition stipulates:

When my grandma was with us, she said to us that she wants to go back to where she was from and be buried in there. So, my dad followed her wailing and brought her back to Shanghai at the last few months of her life. However, he never provided any care to her all the time, he was just following what he was told to do apparently without the love. (P15)

P15's expression of ‘followed her wailing’ describes the internalised defiance of her father's submission. This excerpt exemplifies how P15's father felt compelled to obey his mother's wishes regardless of his personal circumstances while suppressing his emotions, as that could be considered unfilial. Suppressing true emotions in favour of upholding tradition arguably results in outward acceptance of care responsibility but an inward indifference. We see this when P15 recounts that ‘he never provided any care to her all the time, he was just following what he was told to do apparently without the love’. From this statement we can consider the potential negative impact that emerges when society values obedience above willingness or capability to provide care.

Xiao made it crucial to ensure that harmony reigned amongst people, and its principles were expected to be adhered to by everyone. This concept is grounded in reciprocity, however, participants felt children might question the rationale behind ‘payback’:

If you were mistreated by your parents, or you were abandoned by them, but when they get old and want to find you back just for having your care because of Xiao, then what can you do for that? (P13)

These societal expectations were perceived by some participants as unfair:

You might provide care as Xiao required because of the social pressure. But there was no care to you when you were a child, and then you might question yourself why do I need to care [for] my parents now? (P13)

Here, P13 explicitly attributes adherence to Xiao to societal pressure, particularly under circumstances where there are no common grounds for care-giving expectations.

P16 shared an experience about her mother providing hands-on care for her grandmother who was living with a long-term health condition. Recalling the experience, her uncle's wife was caring for her own mother who also had a long-term health condition and their son. ‘My uncle's wife has got a son, and their mother had experienced a very serious disease last year…’. Her uncle assisted her mother in providing hands-on care, and considering that provision of hands-on care was largely celebrated in society as upholding Xiao's principles, he was rewarded in their local community for visibly demonstrating Xiao:

As her [P16's mother] brother did really good job in taking care of their parents, he was rewarded by the hospital and local community, as his story of taking care of parents was told by a nurse, and was published in the local newspaper for others to take as a great example for promoting Xiao. (P16)

It is particularly interesting to note participants' examples of who is celebrated, and this example mirrors societial expectations, which tends not to put personal circumstances into consideration.

Overall, this theme reflects the social pressures within the cultural environment, as participants shared examples of how it tends to emanate from an appreciation of obedience, perhaps without regard for personal circumstances of family care-givers. These pressures to oblige parents without accounting for willingness, ability or availability to provide care could consequently result, for some, in mechanical fulfilment of Xiao, bereft of emotional affection. It can also leave other family members feeling unappreciated or misrepresented.

Evolution of filial piety, Xiao

Participants understood the traditional meaning of Xiao as embodying unquestioning obedience. It was recognised that the power of Xiao was waning, as stated openly in this extract:

The scope of Xiao is reduced, for example, the scope is just contrast, because in the past, if you cut your hair, you disobeyed Xiao, because your hair, your skin is given by your parents, but now it totally depends on ourselves. (P09)

In this example, P09 describes that even something as personal as having your hair cut without your parents' permission would have been seen as infringing Xiao. His comment ‘now it totally depends on ourselves’ emphasises change through the term ‘now’ and the expression that ‘it totally depends on ourselves’ shows a view that there is now a sense of self-determination and self-preservation.

Most participants spoke about the changing nature of Xiao. They appeared to interpret the concept as staying out of trouble and not placing pressure on parents: ‘Health wise, we don't create any troubles for our parents. That is Xiao because we are not bringing more pressure to the parents.’ Participants suggested their parents were also going through a phase of change. The quotation above continues:

…but the parents think that once they keep themselves healthy, make sure everything is OK, they are decreasing the pressure for young people's lives. They are reversing their way of thinking. (P18)

These consecutive excerpts, which both use terms about reducing pressure, demonstrate that P18 felt there was a new reciprocity whereby both parents and children wanted to decrease pressure on each other. Consequently, participants expected government to provide formal services as a viable alternative:

I think the government should think about how to promote the retirement lifestyle and care services that will meet the needs of people in this era. (P15)

Overall, this theme reflects changes in Xiao from one generation to the next and shows a loosening of the ties of obligation between generations. It reflects the sense of independence for younger generations, but with this still hinging on parents' happiness.

Willing but unable

Most participants believed in self-sacrifice to fulfil Xiao for their parents and easily expressed this. P03 was enthusiastic when sharing: ‘I think I really love my parents, I really do. I can stay with them all the time. I can give up my future.’ However, she goes on to express her concerns about whether she would be able to adjust to providing intimate care:

But, something here, I just need time to adapt, like toileting, like bathing, because I never see my parents naked. If I am required to do all these now, I may need more time to get there. But I think I will do all these, and it is very difficult. (P03)

Her hesitation comes through in her use of ‘I think’ which she uses to temper the complete commitment she had expressed just beforehand. There were many participants like her who expressed willingness, yet shared concerns about providing care. P13 expressed a general lack of confidence due to fear of being financially or emotionally overextended:

I don't have any confidence about it … I think not just financial support, but more about emotional support. You will need to share more emotions with your own family, your wife, your children, once you become an adult person, which means less emotions you can share with your parents. So, I think emotional side is an important challenge for me. (P13)

These examples uncover some nuances surrounding the physiological and psychological demands associated with anticipating being wholly responsible for older relatives' wellbeing, which comes with additional cultural and societal pressures. Drawing from his personal experiences, P07 illustrates the challenge he had of being an only-child who is geographically distant from his parents:

I was visiting [a large UK city] for three months, and my mum got serious illness. It was urgent. She had surgery in Beijing … and they didn't tell me, because I was in [a large UK city]. I was overseas, and afterwards, maybe a month later my dad told me this happened, and I didn't know that. I feel very disappointed. I feel like you didn't do your job as a son. (P07)

On reflection, he felt guilty for not meeting certain societal expectations, hence, ‘I feel like you didn't do your job as a son’.

This theme reflects the participants' feelings regarding their sense of responsibility and their ability to fulfil several demands against all odds. Despite their willingness and motivation to take up the responsibility of selflessly caring for their parents, the participants did not feel they had enough preparation or support to meet either short or longer-term needs.

Concerns about formal care services

Needs of family members varied, but generally, in preparation for when their parents would require care, participants foresaw a need for formal care services. However, poor quality of care was concerning to some participants and was associated with formal care-givers' low literacy level, low socio-economic status, poor training and, consequently, led to attitudes that stripped older relatives of respect and dignity:

They are not very professional, a lot of the carers you get there. They couldn't cook … And a lot of them are from poor families, so they are not educated. They can't read, can't write, and they have really strong accents. So, communication is a problem. Giving the elderly medication is a problem and just basic moving, handling. (P02)

With my other gran, this person was trying to give her a bath. The door was wide open and she was using a really rough cloth, just like she was scrubbing a pig basically. They don't treat them like humans because they don't really think about them from their family perspective. It is just a job. They've got the money and that is it. (P02)

Due to the poor treatment witnessed, which was viewed as a consequence of the formal care-giver's inability to see the older person as their own family, P02, perhaps unknowingly, reinforces the mandate of traditional Xiao on family members as primary care-givers. The assertion that formal care-givers appraise their profession as ‘just a job’ with financial security being the primary motivation could imply the rejection of a transactional relationship, opposed to the relationship between parents and offspring based on a motivation of re-paying past help.

Lack of trust in external influences or involvement emerged quite frequently in the focus group discussions. The following example highlights that, on one hand, government-mandated Xiao could encourage individuals to meet their filial obligations, on the other hand, there is a potential for individuals to experience dissonance when individuals raised to uphold Xiao, as a rule of society, do not see Xiao enacted:

Xiao is something that is the responsibility, forced by the country, because in China we actually have a lot of people who are not supporting their older parents and this concept of Xiao makes people to take more responsibility, which will take pressure off the government. (P19)

The approach adopted by the government, alluded to by being ‘forced by the country’ and the statement ‘which will take pressure off the government’ could be down to the perceived inadequate governmental responses to the challenges of an ageing population, leaving family members unsupported in their care-giving role.

Furthermore, some participants asserted there was the potential for business owners to exploit offsprings' desire to have the best for their parents, using Xiao to make excessive profits:

Apart from the luxury decoration of the room, most [of] the services provided are also for making money from people. They are utilising the initiative of our Xiao to our parents, and then making profit on it. (P15)

This theme overall highlights that even if offspring were willing to explore options for care outside the traditional family-based system, there are several barriers to securing adequate public (governmental) and private services needed to provide support for the family care-givers of older relatives.

Discussion

Change in the nature of Xiao has undoubtedly been accelerated due to a plethora of changes in China. Most recent studies have focused on outcomes for care-givers who are from generations before those focused on in this study (e.g. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shao, Li, Liu, Xu and Du2018; Tang, Reference Tang2021). Within the ethos of Xiao, Chinese parents typically seek the highest education option affordable for their offspring, and the saving culture alongside extended-family support makes Western tuition affordable (Liu, Reference Liu2016). This ambition appears deeply rooted in a culture that expects parents to sacrifice themselves in their offsprings' best interest, however, little to no attention has been paid to the implications of the transnational mobility of Chinese students for the reciprocal aspects of their future care responsibility. The rapid increase in the number of women devoting their time to enhance their knowledge by attending tertiary education in many regions of Asia (Burhanullah and Munro, Reference Burhanullah and Munro2020) could continue to give rise to gender equality. However, since women are expected to provide hands-on care, this poses a significant threat to the traditional family caring system. More so, irrespective of gender, increased urbanisation in China and globalisation could create enormous pressures influenced by values attributed to Xiao. With the OCP programme also being a major catalyst, our findings suggested that families could be susceptible to tensions in future, as ongoing demographic and societal transitions could result in prospective care-givers being unable to enact Xiao as expected. They have to earn a living, yet also re-pay parents for past help in an effort to make them proud. In this context, it is imperative to explore the attitudes and expectations of the generation affected by the OCP and this current study is the first to address this by looking at Chinese students in England regarding their future care-giving roles.

The perceptions of UK-based Chinese students regarding future care roles and responsibilities are influenced by their understanding of filial expectations. Evidently from our study, all participants saw Xiao enacted by their parents, conveying that families play a huge role in mutual support. Also evident was how the transmission of Xiao varied between families. For instance, whilst expressing their positive and negative views of Xiao, participants exposed an apparent three-way tension between the wish to fulfil Xiao, practical ability and understandings of Xiao. The tension that was illuminated in participants' contextual cultural discourses pertained to the authority and influence of Xiao. Our findings also showed that there was an inevitable social pressure to fulfil Xiao even when unrealistic for some individuals. This was especially highlighted in cases where offspring might be expected to provide care despite challenging factors such as conflictual rellationships within family history. Although caring for older relatives is still mostly seen as an obligation, findings show that the socio-demographic transition in China is causing a shift in attitudes. Consistent with these findings, a study with older Chinese immigrants in Canada suggested that older generations' equal valuation of ‘emotionally oriented’ filial piety (Xiao) and ‘behaviourally oriented’ filial piety (Xiao) could be weakening the traditional message and complicate filial perceptions (Zhang, Reference Zhang2022). Likewise, another study of Chinese immigrants in the United States of America (USA) stated that the younger generation reported distant relationships with parents compared to older generations, but they still worried about disappointing their parents if unable to meet filial obligations (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Byram and Dong2020). As such, it is important to understand that Xiao expectations, the reactions of others in the social context and the systems of support afforded to individuals by their culture influence perception of stressors (Aldwin, Reference Aldwin2007). Thus, cultural values have implications for individual coping responses (Knight and Sayegh, Reference Knight and Sayegh2010).

A recent scoping review exploring the stress and coping mechanisms of care-givers of older relatives living with long-term health conditions in China showed that care-givers are subjected to extensive demands associated with their caring responsibility (Bífárìn et al., Reference Bífárìn, Quinn, Breen, Wu, Ke, Yu and Oyebodein press). Chinese care-givers are commonly left in limbo and are subject to both discrete and continuous stressors (Bífárìn et al., Reference Bífárìn, Quinn, Breen, Wu, Ke, Yu and Oyebodein press). The proliferation of stress is a given, as those who are actively providing care experience care-giving burden (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Lou2015; Du et al., Reference Du, Shao, Jin, Qian, Xu and Lu2017). Our participants were motivated by love to care for their parents in the future, but were aware of the inevitable demands of providing hands-on care, as their parents are doing for grandparents. Due to stress, the provision of care can be reduced to an affectionless process. Considering this, coping efforts from the participants' perspectives could illustrate attempts to re-interpet tradition to fit better with current reality, in an endeavour to achieve cognitive consonance and so reduce tension. The result of this attempt at balance appeared to shape prospective care-giver's thoughts about their future care-giving decision-making processes. In this current study, most participants anticipated deriving satisfaction from fulfilling care-giving responsibility, hence, the act of fulfilling Xiao was seen as positive (Quinn and Toms, Reference Quinn and Toms2018; Pysklywec et al., Reference Pysklywec, Plante, Auger, Mortenson, Eales, Routhier and Demers2020). Although willingness to care for older relatives has been found to be significantly related to preparedness to care (Shyu et al., Reference Shyu, Yang, Huang, Kuo, Chen and Hsu2010; Parveen et al., Reference Parveen, Fry, Morrison, Fortinsky and Oyebode2018), in this current study, participants' concerns about being unable to fulfil Xiao adequately were related to the demands of modern life and being unprepared to provide personal care or emotional support to meet societal expectations. Previous studies have suggested that care-giving burden can be associated with poorer psychological wellbeing, particularly concerning discrepancies between care-givers' idealised expectations and the reality of their competence in practice (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Chang, Wong and Simon2012; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Byram and Dong2020). Such discrepancies, as well as the lingering practice of traditional filial piety, could leave future care-givers susceptible to adverse experiences, making the study of willingness and preparedness to provide care pertinent. As such, findings from our study suggest that an intervention to improve preparedness could help prospective care-givers sustain their willingness to care over time. In order to prevent the positive aspects of care being overshadowed by the pressures of care burden, systems to support offspring practically, especially in respect to care and services, need to be put in place.

Confucian beliefs of filial piety (Xiao) create the propensity for offspring to de-prioritise self. This results in social pressure being a part and parcel of the cultural environment, leading to the tendency to place demands on offspring without paying enough attention to their stressors (Bífárìn et al., Reference Bífárìn, Quinn, Breen, Wu, Ke, Yu and Oyebodein press). Despite Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Zhang and Zhang2020) suggesting that there has been a rapid change to traditional filial piety due to older people becoming less dependent on offspring, our findings suggested otherwise. Due to the combination of societal influences, in addition to the impact of the OCP, in some cases, future care-givers will have no siblings, aunts or uncles to consult whilst figuring out how to meet the needs of their older relatives. Social support received from family members, and not friends, serves as a protective characteristic against depression (Yang and Wen, Reference Yang and Wen2021). Thus, participants emphasised the relevance of family harmony and belongingness within a collectivist society, which implied that offspring could still retain the perception that they should provide hands-on care for their parents, even if parents advise otherwise. One major barrier for current study participants was concerns about poor-quality formal care (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shao, Li, Liu, Xu and Du2018; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Wan, Xie, Chen and Li2019b). An international report, which presented a case study for China, highlighted that nursing homes can be considered as a panacea given the significant reduction of family members available to provide care (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Cyhlarova, Comas-Herrera and Lorenz-Dant2021). However, this option may not be acceptable to older people (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Shi and Li2019) or offspring (Tang, Reference Tang2021) as supported by our findings. For those who prefer to provide domiciliary care, it is equally important to stress the need for adequate resources from the state for community-based support, as otherwise, family care may become less of an option in the future (Lin, Reference Lin2019). Furthermore, future care-givers could be hindered by structural barriers characterised by deficits in old-age care training and disjointed inequitable services (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu, Tan, Li, Lou, Chen, Chen, Fletcher, Carrino, Hu, Zhang, Hu and Wang2021). Long-term care settings are facing challenges characterised by poor staffing levels, underpaid staff and high staff turnover, resulting in poor-quality care (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cohen, Cong, Kim and Peng2021). Also, there are ongoing debates in China regarding the accessibility of long-term care needs assessments for older people living with moderate physical or cognitive impairment, and the sustainability of health insurance systems (Du et al., Reference Du, Dong and Ji2021). Lack of adequate services will therefore raise challenges for the younger generations in their attempts to align their individual understandings of Xiao to the pragmatic reality, especially in the context of balancing work–family life with future care-giving responsibilities.

In the context of struggling alone to reconcile the key messages of their upbringing (to be autonomous and also to fulfil Xiao), it is imperative that attention is paid to individual perspectives on care-giving, not least with these transnational returnees who might not be in close geographical proximity to parents due to professional ambition. It is important to stress that the financial implications could be another stressor for those without high-paid jobs as parents of an only-child would more likely need financial support compared to parents with more than one child (L Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Ding and Qiu2019). In an effort to combat spiralling negative thoughts, Confucian beliefs in China would encourage future care-givers to be stoical by containing their emotions, and reframing inner thoughts and desires (Cheng et al., 2010, cited in Au et al., Reference Au, Shardlow, Teng, Tsien and Chan2013). However, current care-givers have been found to experience more psychological stress, as opposed to physiological or financial stresses (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Wan, Xie, Chen and Li2019b). In light of our research, future care-givers are likely to also be exposed to significant psychological stress, so attention needs to be given to psychological aspects of future care-giving.

Practical implications

Based on the study findings, there are a number of practical implications that we consider. If the lack of adequate health and social support persists, prospective care-givers could be overwhelmed by demands associated with care. Irrespective of their work status, extensive care-giving demands could erode the positive aspects of care, leading to poor quality of care or possibly to abusive situations. This assertion is consistent with studies in China and the USA, where some older people have been subjected to abuse and maltreatment by their relatives (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Yan, Chan and Ip2018, Reference Fang, Yan and Lai2019; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Sun, Marsiglia and Dong2019; Chao et al., Reference Chao, Li, Lu and Dong2020). Therefore, future ageing policies in China should develop sensitive interventions to promote the wellbeing of both offspring and parents. These policies must adequately inform health service design and increase funded support services to improve care provision adequately and reduce creeping negativity that can develop in circumstances where offspring experience dissonance related to their roles and identity as family care-givers. In this respect, family care-givers, health and social care practitioners, service commissioners and service managers need education and training around the implications of distinctive responses to fulfilling Xiao, to aid the wellbeing of prospective care-givers and older relatives.

This is equally an issue for countries like the UK where people from minority ethnic groups are underrepresented within formal services for older people. For example, Baghirathan et al. (Reference Baghirathan, Cheston, Hui, Chacon, Shears and Currie2018) suggested a dearth of evidence regarding the needs of Chinese family care-givers in the UK. Also, lack of inclusive services within communities continues to deter people from using services (Arblaster, Reference Arblaster2021). Therefore, families must be supported in a sensitive manner that respects cultural values. This would match the ambition of the National Health Service long-term plan (National Health Service, 2019) and, in turn, address the need for transformation in social care towards better personalised care (Alzheimer's Society, 2021). It is crucial to enable people to make choices and give them control over their services. To ascertain this, service commissioners, providers and professionals need to gain the confidence to support people to age well, better address health inequalities, accommodate ‘unconventional’ requests by recognising cultural sensitivities and, ultimately, be responsive in their approaches.

Strengths and limitations

A potential limitation of this study is linked with the outsider status of the researchers, as cultural nuances might not have been understood. However, this was also a potential advantage as participants may have been more open in responding to questions raised by ‘an outsider’. In addition, BZ was able to advise on cultural nuances as he understood Chinese society from the inside. The similarities between the cultural context of the lead researcher, OB, and that of the participants, could have led to personal bias infiltrating data interpretation. This was, however, resolved by the active involvement of other researchers in the analysis. Participants were all university students who came from affluent backgrounds. As such, a class bias could have been reflected in the attitude of some participants, however, we did wish to explore perceptions of future care-giving in this particular demographic. Having a more gender-balanced sample might have provided more insights, which we have not been able to capture within existing data. Our participants included six who had siblings due to some allowed exceptions to the OCP. As such, some aspects of future care-giving relating to those affected by the OCP might not have been wholly captured. Participants did not contribute to the development of the final themes, which could have reduced potential bias from the research team. However, this issue was attended to by ensuring that BZ checked the plausibility of the research findings.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that Chinese culture influences the process of care-giving both positively and negatively. Given the significance and the changing nature of Xiao, how the socio-demographic issues interact with balancing work and care, the impact of the OCP on availability of care-givers and the challenges associated with accessing statutory support, it is crucial to understand the perspectives of prospective care-givers and their support needs. Researchers need to focus on developing and evaluating tangible interventions that are sensitive to individual circumstances and the influence of culture on care-giving responsibilities, reflecting a more nuanced understanding of care-givers' identity. This will inform services that will sustain family and cultural values and improve the experiences of transnational students (at home or away) when caring for their older relatives.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Research England: Quality Related Global Challenge Research Fund (QR-GCRF).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was granted by the Humanities, Social and Health Sciences Research Ethics Panel, University of Bradford on 10 October 2019.