1 Understanding Risks in the Renaissance

Preface

Risk was a recognized reality in the Renaissance. A raft of risks faced those who produced, commissioned, and purchased art in the Renaissance, but the profound impact of risk on the marketplace of goods, services, and ideas that enabled the Renaissance art business to thrive has not been investigated. Nevertheless, numerous studies published in the last few years by historians of premodern Europe have addressed the broader topic of risk (see Reference SchellerScheller, 2019a; Reference BakerBaker, 2021; Reference CeccarelliCeccarelli, 2021; each provides an extensive bibliography). As Nicholas Baker notes, the term rischio [risk] “peppered the correspondence of merchants across the Italian peninsula, a constant element in the calculation of the profitability and viability of any investment or speculation” (Reference BakerBaker, 2021: 97).

Baker’s book focuses on a new conception about the future: around the year 1500, Italians started to see it as unknowable. An increased awareness of chance and change led to the belief that tomorrow might operate by different rules than today. Nevertheless, as Baker documents, the transformation in ideas about futurity hardly led to fatalist behavior. People still took actions to increase the possibility of success and diminish that of disaster. This realistic and pragmatic approach to the future underpins this study. This study’s five sections discuss a widespread, but hitherto unstudied, phenomenon in the art world. Participants took actions to reduce the likelihood and consequences of risks in both the patronage-based system used across Europe and the more modern open markets that developed first in the North. Moreover, systemic developments, such as the evolution of artists’ associations, helped to reduce risks to levels participants found acceptable. This volume employs a new methodology, built around concepts from risk analysis and decision theory. Specifically, it identifies the sources of losses suffered by artists, patrons, purchasers, and dealers. Those sources fall into two broad categories: production risks and reception risks. Production risks encompass the array of mishaps that occur from the time a work of art is conceived until its final placement. For artists working on a commission, the most frequent risk was delayed or insufficient payment. For patrons, late delivery of a painting or sculpture was the most common risk, but other documented hazards, still all too familiar today, included shoddy materials or practices, damages during transportation and installation, and forgeries.

Success in the art world required two steps: effective production followed by favorable reception. Reception risks arise when a patron, a buyer, or members of the intended audience found a work displeasing, inappropriate, or offensive. When we asked colleagues and students to name a consequential risk in the art world, most named public scorn. Such scorn generally emerged after a work of art was put on view in a palace, church, piazza, or marketplace. The criticism might be inappropriate imagery or substandard skill. Reception risks imposed financial and social costs that landed on artists, patrons, and buyers.

Sections 2 and 3 explore production and reception risks, respectively. Some risks are much harder to assess, or even foresee, than others. In response, our methodology distinguishes among reliable risk, uncertainty, and ignorance. Our primary focus is Italian art made between roughly 1400 and 1650, the period addressed in this series. Paintings and sculptures mentioned in contemporary records receive the greatest attention. Most of these works were commissioned to decorate ecclesiastical spaces, town halls and squares, and private palaces. These sections also address other geographic areas, including the open art market in Northern Europe. Germany and the Netherlands is the subject of Section 4, written by Larry Silver, a leading specialist of Flemish and Dutch art. The geographic emphasis of this study capitalizes, in part, on the plethora of published sources, and especially those by two celebrated sixteenth-century authors: Giorgio Vasari in Italy, and Karel van Mander in the Netherlands. Both wrote biographies of scores of artists; their accounts remain fundamental sources for Renaissance risks and failures. As noted by Patricia Rubin, “Vasari’s portrayal of figures from the past was based largely on instructive probabilities, which abounded, not actual facts, which were limited … Utility was the measure of Vasari’s truth” (Reference RubinRubin, 1995: 160). This “instructive probabilities” approach to history was followed by van Mander. Some of their stories are exaggerated, and others are probably invented. Nevertheless, all or most were considered plausible by their readers, including those of today. Their accounts, together with news about other risky art transactions, spread across Europe the knowledge about a wide range of losses.

The fifth and final section considers the fundamental role that trust played in pre-modern society, most notably in commercial interactions such as commissioning, buying, and selling art. Protagonists in the art world deployed an array of strategies to constrain risks. Three case studies illustrate three very different strategies in different centuries and regions. The analyses throughout this Element could have been made with examples of art made or sold in Spain, France, and England, to mention three major areas underrepresented in the discussions below. We expect that some readers could substitute the case studies discussed in this study with others from different time periods and areas of premodern Europe, and we hope that some will do so in the future.

Why, despite looming risks, did an increasingly large number of people acquire works of art? Because those works offered significant benefits for purchasers and patrons. Those benefits are explored in our earlier volume, The Patron’s Payoff, which focuses on conspicuous art and architecture in Renaissance Italy (Reference Nelson and ZeckhauserNelson and Zeckhauser, 2008). These works allowed patrons and purchasers to honor their families, adorn their cities, and glorify God. For Catholics, this last benefit was believed to shorten the patron’s time in Purgatory. Equally important, and centuries before mass media and public relations agents made it easy, art helped patrons and owners bolster their reputations. We argued that the key players in the Renaissance art world weighed expected benefits against expected costs and concluded that the former outweighed the latter when they proceeded to commission art.

This Element focuses on the flip side of the coin: the risks of art and the costs these risks imposed. Even where open markets developed for prints and paintings – first in Northern European cities, and then in Italy and Spain – buyers confronted risks such as substandard materials or forgery. Everywhere a massive risk threatened, when governments fell or religious sentiments shifted, depictions of rulers or saints might be destroyed. Given the difficulty in mitigating production and reception risks, and of assessing those risks, many patrons, buyers, and artists expected to benefit from their activities, but wished in retrospect that they had chosen differently.

Selection Bias: Favoring Success

This volume counterbalances the widespread tendency to view the history of Renaissance art as a glorious sequence of successes. In that Pollyannish view, prominent individuals acquired works that delighted them and other viewers, and so the global patrimony expanded. But just as accounts of wars are disproportionately written by the victors, the successful fruits of Renaissance art production were far more likely to be prominently displayed, approvingly admired, and discussed in writing than those unsuccessful. From Amsterdam to Naples and Madrid, most pieces that survived their times and reached ours were regarded favorably by their original audiences. As a result, standard assessments of Renaissance art greatly underestimate the risks that were involved. The differential attrition of unsuccessful art produced what decision theorists call “selection bias.” That concept applies whenever a sample of objects or beings, due to choices made by individuals or organizations, ends up being far from representative of the whole. Today, for example, worse drivers are more likely to purchase high-value collision insurance. As a result, a sample of such buyers has a greater fraction of poor drivers than the general population of motorists.

The biases favoring successful Renaissance art increased over multiple historical stages. First, pieces that displeased were often not put on view, hence less likely to be written about by contemporaries in treatises, journals, and guidebooks. Moreover, historical accounts tend to lose track of works that disappointed. The highly informed contemporary accounts by Vasari and van Mander show a different type of selection bias. When they wanted to present an artist as successful, they gave vastly more attention to works that avoided production problems and enjoyed a good reception. We strongly suspect that the writings of Vasari and Van Mander not only underrepresent failures for the period but also overrepresent them for artists and patrons they did not like.Footnote 1

Second, documents relating to elite artists, patrons, collectors, and institutions – those who were more likely to succeed in the art game – had superior survival prospects. Indeed, archives hold far more documents about rulers than about their subjects. Moreover, the quantity and detail of records after 1500 far exceed those from earlier periods. Third, the records that do discuss art very rarely address social costs, such as the hazards of an unflattering portrayal. Fourth, modern scholars traditionally focus on the art and artists considered influential, interesting, and intriguing. The numerous exceptions to each of these observations hardly undermine the strong bias toward successful art in texts written from the Renaissance to our day. When compared to the most popular and written-about works of the period, an analytic tally of its disappointments, to follow, contributes to a more balanced assessment of failures and successes.

Histories of Renaissance Italy suffer from another selection bias: Florence gets undue attention. For the pre-modern period, more documents survive in Florence than in most other major European cities, though it was never a major political or military power. In part, Florentines seem to have been more assiduous record keepers than others. Moreover, attention is contagious. Since the late nineteenth century, art collectors and art historians have devoted more attention to works by Florentine artists than those from elsewhere. Given these forces, some observations about Italian Renaissance art and society undoubtedly reflect practices more prevalent in Florence than in other areas.

Premodern Understandings of Risk

Risk has been a central topic of discussion concerning finance, across many realms, for hundreds of years. In the United States, the Great Depression in the 1930s gave risk a starring role in discussions of macroeconomics and the economy. In the first years of the twenty-first century, however, many economists claimed that “the business cycle had been conquered.” Risk regained prominence in the Great Recession of 2007–9. In recent years, and in studies around the globe, risk analyses have been widely applied to a vast range of topics. Climate change and pandemics have put the concept of risk front and center for both national leaders and ordinary citizens. Other events thrust risk references forward into sixteenth-century England. Shakespeare repeatedly used such phrases as “ten to one” or “twenty to one” (Reference Bellhouse and FranklinBellhouse and Franklin, 1997). The bard’s intended readers understood that these expressions indicated an intuitive, albeit imprecise, quantification of risk.

Risk was everywhere in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Indeed, in some categories, such as illness and early death, it appeared in much greater abundance than today. Deep concerns for the uncertainties of the afterlife were the norm, given that one knew little about one’s prospects for Heaven, or how much time one would have to spend in Purgatory. Then, as now, merchants and bankers had to face ordinary risks when acquiring assets, such as textiles or bank deposits, and then transforming and selling them as clothes or loans. Miscalculations could have dire consequences and, in many cities, both rich and poor suffered downdrafts and updrafts in their finances. A recent study argued, unexpectedly, that stability in relative wealth “was unusual rather than common among families in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Florence” (Reference PadgettPadgett, 2010: 371).

To better grasp a premodern understanding of risk, scholars have turned to a very large body of Medieval and Renaissance texts, analyzed extensively in recent decades by historians of economics, ideas, and society, but largely overlooked by students of cultural products. The concept of risk, and the term itself, first appears in documents from the mid-twelfth century and quickly spread across the Mediterranean region. In a commercial agreement from 1156, a certain Jordanus confirms that he received funds from Arnaldo Vacca which he would take to Valencia, and then possibly Alexandria in Egypt, in order to trade there “at your risk” (ad tuum resicum) (Reference SchellerScheller, 2019b: 3). James Franklin and Giovanni Ceccarelli have both clarified the fundamental importance of risk in juridical and theological discussions of usury dating from the late Middle Ages, two centuries before the works discussed in this volume (Reference CeccarelliCeccarelli, 2001; J. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 258–89). Shortly after 1200, Peter the Chanter argued that a buyer or a seller does not commit the sin of usury “if he exposes himself to the risk of receiving more or less” (J. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 263). Already in the late 1200s, in his influential volume, On Sale, Purchase, Usury, and Restitution, Peter John Olivi referred to the general agreement that “capital should profit him who runs the risk of it” (Reference CeccarelliCeccarelli, 2001: 614; J. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 263). Ultimately, this view reflects ancient Roman law, which established that those who bear risk should get the benefit. This understanding of risk, securely embraced by the modern theory of finance, is so familiar today that our only surprise may be to find it adopted in medieval Europe and earlier in ancient Rome.

Few people today read technical studies on risk and finance. However, through a process of intellectual osmosis from the worlds of economics and finance, the need for risk to be compensated now flows in the mainstream. Even in the Renaissance, that recognition flowed strongly in tributaries. Certainly, merchants learned some of these basic tenets in abacus schools, and churchgoers heard them expounded in sermons. San Bernardino, a highly popular Franciscan preacher in mid-fifteenth-century Italy, explained that risk-taking underpinned commerce, and provided the justification for legitimate profit (Reference CeccarelliCeccarelli, 2001: 621). Court decisions also upheld the principle that risk-taking deserved reward. This news circulated among merchants, bankers, and their clients.

In the past, as today, sophistication about risks varied significantly across the economy. Annuities and marine insurance, two financial instruments created in the 1300s, reflected the most developed understanding. Across Europe, but especially in Germany and the Low Countries, local governments often raised funds by accepting a sum of money in return for a stated annual income for life. In his 1307 Treatise on Usury, Alexander Lombard noted that the just price of an annuity could be established after considering “the age of the buyer and his health, and the risks concerning the profits from the possessions” (J. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 270–1). Even at this early date, financial players had identified risk factors, such as age and health, for pricing annuities.

For annuities and some forms of commercial insurance, most notably insurance on goods shipments, risk became commodified. This essential point was stated explicitly in numerous texts. In 1403, the Florentine jurist Lorenzo de Ridolfi wrote of insurance wherein “when you send your merchandise by sea or land to certain parts, and I take upon myself the risk and agree that for every 100 of value of that merchandise, you pay me a certain quantity of money … something is given for something done” (Reference CeccarelliCeccarelli, 2001: 620). This fundamental concept of risk as something concrete derives from the decision of Baldus, an earlier jurist, who wrote that no usury is involved where there is a genuine quid pro quo. One example is when “there is an accepting of risk, in return for giving something” (J. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 276). Surprisingly, though a highly advanced international market developed for marine insurance, policies were not generally available for ground transportation or for many other activities where risks lurked. Renaissance merchants and government officials thought about risk differently than we do today but, crucially for this study, individuals from many walks of life had risk on their minds.

Reliable Risk, Uncertainty, and Ignorance

The word “risk” embraces broad territory. To most people today, risk represents the broad category where outcomes are unknown and something of value may be lost.Footnote 2 We are all familiar with losses that involve money, such as sour investments or wrecked cars, that are readily compensable with money. However, some losses, such as the loss of one’s good name, what Reference Bourdieu and NicePierre Bourdieu (1984) famously called “symbolic capital,” are difficult or inappropriate to measure in monetary terms.

For specialists in economics and decision theory, the term “risk” applies only in contexts where probabilities can be estimated with reasonable precision, such as for summertime weather. On television tonight, the weatherwoman might predict a 10 percent chance of rain tomorrow and, in reality, it will rain on just about 1 in 10 days. To express the same idea, a Renaissance sailor or farmer might say, less precisely, that rain was quite unlikely. In either case, the intended audience was aware of the risk and believed that it was established with some degree of reliability; thus, people could make plans accordingly. In the fifteenth century, for example, the city of Nuremberg created an early warning system for floods based on predictions made by observers upstream on the Pegnitz river (Reference SchellerScheller, 2019b: 6). Risk also applies to games with cards and dice. Significantly, these activities provided the bases for the first systematic study of probability, The Book on Games of Chance, written by the Italian mathematician Girolamo Cardano in the 1520s and revised in the 1560s but not published until 1663 (J. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 298).

The term “uncertainty,” in contrast, indicates situations where the possible outcomes are known, but their probabilities are hardly known. This distinction was made by risk specialists only a century ago (Reference KnightKnight, 1921). Throughout the worlds of Renaissance art and finance or, for that matter, the world of today, situations characterized by uncertainty are common; situations of risk are rare. This volume uses “risk” in the colloquial sense: it applies the term to all situations where the outcome is unknown but the prime concerns are downside results. We introduce the term “reliable risk” for situations where either the probabilities are fully known, as with dice rolls, or where probabilities are closely estimable due to a great deal of experience, such as weather predictions. “Uncertainty” maintains its traditional use, to describe situations where probabilities are unknown, as say whether a particular commission will be fulfilled on time.

These categories generally align with the terminology of Giovanni Ceccarelli, the leading specialist on Renaissance marine insurance. He identifies two main categories of sea risks, “structural” and “contingent,” based on his reviews of hundreds of extant policies and payments (Reference CeccarelliCeccarelli, 2021: 84–5). Structural risks are stable and predictable, such as the specific journey, the type of merchandise, and its degree of fragility. Contingent risks are based on factors subject to quick change, such as piracy. Most structural risks are reliable risks, and all contingent risks are uncertainties.

The usual way to gauge a reliable risk is to secure lots of data on similar situations. A successful cloth vendor, in the Renaissance or today, would know reasonably well the likelihood that a client can be nudged to a higher-priced fabric, or that such efforts will lose a sale. Similarly, the sale of standard products, such as prints, maps, or illustrated books, would offer enough experience to yield reliable risk assessments (Reference CarltonCarlton, 2015). As discussed in Sections 2 and 4, at times a successful publisher or agent could accurately estimate the probability of finding a buyer for images depicting a particular genre or locale.

Regulations kept some grave dangers at bay. Across Europe, guild regulations prohibited painters from substituting expensive ultramarine with azurite or a mixture of the two (Reference Kirby, Neher and ShepherdKirby, 2000: 21). Artists had to know where to purchase materials of reliable quality. Repeat purchases and merchant reputations helped. In addition, several merchant handbooks even explained how to test ultramarine for its purity, thus helping to reduce the risk of deceptive substitution. These examples, where various instruments, actions, and techniques helped to trim uncertainties back toward reliable risks, represent exceptions. In the Renaissance world, few risks, whether of production or reception, offered the repeat experiences or the secure regulations that would enable them to be reliably assessed. Moreover, as noted by the sixteenth-century Florentine historian Vincenzo Borghini, “the nature of weights and measures is both very uncertain and very unstable. They vary from moment to moment, place to place and thing to thing, so much so that to reduce them to a fixed and equivalent term is very difficult, if not impossible” (Reference LugliLugli, 2023: 3). Hard-to-predict human behavior or misbehavior was often the source of risk. All too often, situations were sui generis.

In his discussion of structural risk, Ceccarelli noted that insurance contracts and related letters provide very detailed information about merchandise to be shipped, and that insurers were aware of which objects were fragile or suffered from humidity. Unfortunately, the historical record cannot determine the impact of these reliable risks on premium rates. A parallel in the art world relates to Sebastiano del Piombo’s Pietà (Madrid).Footnote 3 A letter from 1539 explains that the painting on slate was sent to its patron in Spain by sea because it was too fragile to transport by land with a mule train (Reference NygrenNygren, 2017: 63 n. 3). This illustrates a common trade-off where the risk for art is concerned. In this case, the greater risk of land travel outweighed its greater benefit of swifter delivery.

In the Renaissance art world, most production risks and all reception risks derived from uncertainties. Players could anticipate what hazards might arise but had insufficient means to assess their likelihood. Nevertheless, insurers took action to dim their risks. When marine insurers learned that pirates were active in a certain area, they demanded a higher premium from vessels traversing it. A Venetian document from 1457 neatly sums up the concept that the degree of risk determines the cost of premiums: “more risk equals more [higher] premium” (Reference SchellerScheller, 2019b: 4). Shippers could either pay up or select another route.

Sometimes, the shipped merchandise included art, as in a well-documented case in 1473 concerning a galley traveling from London to Pisa. In addition to cloth and alum, it carried Hans Memling’s Last Judgment (Figure 1), an altarpiece commissioned by Angelo Tani in Bruges for his chapel in Florence. After pirates attacked the ship, they brought all the booty to their native Gdansk. The altarpiece, never liberated, stands there today (Reference Daniels and EschDaniels and Esch, 2021: 671–2).

Figure 1 Hans Memling, The Last Judgment, c. 1467–71, oil on panel, Muzeum Narodowe w Gdánsku, Gdánsk.

Reference Van Mander and MiedemaVan Mander (1994: 85) recounted a shipping mishap, where action reduced the risk. When Rogier van der Weyden’s Deposition (Madrid; Figure 2) was sent from Flanders to the King of Spain, the ship sank. Fortunately, the painting “was fished out and because it was very tightly and well packed it was not damaged too much.” Van Mander’s readers not only knew about the uncertainties of marine transportation but also how losses could be reduced by selecting safer routes and by packing goods more securely.

Figure 2 Roger van der Weyden, Deposition, before 1443, oil on panel, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Reliable risks and uncertainty apply when potential hazards are known. Many hazards arise from causes that cannot be identified in advance, or perhaps could be identified but are not. Economists have recently coined the term “ignorance” for these situations, which occur very often in the art world when some possible outcomes are unknown or unknowable (Reference ZeckhauserZeckhauser, 2006; Reference Roy and ZeckhauserRoy and Zeckhauser, 2015). For example, in 2019, virtually no one envisioned a pandemic that would shut down the world; a half millennium earlier, virtually no one could foresee the Reformation-inspired iconoclasm in German churches.

The sociologist Reference LuhmannNiklas Luhmann (2002) distinguished risk from danger, focusing on predictability. The first dealt with predictable unknowns, the latter with “unknown unknowns,” akin to what Knight first labelled uncertainty. Luhmann was not concerned with situations where even the state of the world could not be foreseen, what we label ignorance. He focused on risks that flowed from the decision made by a group or individual, as opposed to, say, natural (floods) or societal (inflations) causes. To understand risk in an historical context, as Suzanne Reichlin rightly noted, social motivation, interpretation, and assessment must complement Luhmann’s concepts (Reference ReichlinReichlin, 2019).

To summarize, we identify three classes of risk: reliable risk (probabilities can be reasonably assessed); uncertainty (probabilities hard or impossible to assess); and ignorance (even possible outcomes are not known). Given that few situations in the Renaissance art world can be considered reliable risks, the latter two classes animate this volume. Players were very aware of many uncertainties and could try to avoid negative outcomes. However, when ignorance reigned, planning slept.

A recurring but often unimagined development was the destruction of monuments following a revolution in religion or rule. The most significant Renaissance example was the Protestant Reformation. Its significant role in the removal and destruction of art is explored in Section 4. Political upheavals could lead to an official damnatio memoriae, or the condemnation of memory. In 1340, popular sentiment in Arezzo turned against its long-deceased former lord and bishop, Guido Tarlati (Figure 3). His opponents attacked his marble tomb in the cathedral and chipped off his image in the scenes celebrating events from his life. (The portraits were restored in the eighteenth century; Reference Pelham, Cannon and WilliamsonPelham, 2000.) Similarly, in 1506, Giovanni Bentivoglio, Lord of Bologna, was expelled. This inspired the demolition of his family palace and the subsequent loss of several paintings by both Lorenzo Costa and Francesco Francia (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 3:163, 4:25). Bentivolgio’s fall also led to the destruction of two statues of Pope Julius II: Michelangelo’s bronze at San Petronio and Alfonso Lombardi’s stucco work at the town hall (Reference HendlerHendler, 2021: 121). Papal portraits were not safe, even in Rome. Soon after the death of Pope Paul IV, in 1559, civic officials had a stonecutter cut off the nose, ears, and right arm of a marble statue of him. After the head was severed, it was cursed and mocked by children (Reference HuntHunt, 2016: 186–7).

Figure 3 Agostino di Giovanni and Agnolo di Ventura, Monument to Guido Tarlati (detail), 1330, marble, Cathedral, Arezzo.

Ignorance is often associated with much less dramatic events. The remodeling of a palace or church often led to works destroyed, as happened to the Vatican frescoes made for Pope Nicholas V by Piero della Francesca and Fra Angelico. They were demolished by renovations dictated by Pope Julius II and Paul III, respectively (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 3:18, 32). Neither the original patrons nor the artists foresaw the potential for such losses; hence they made no plans to avoid them.

We review our two categories of risk sources – production and reception – and our three classes describing its properties – reliable risk, uncertainty, and ignorance – with the salient example of the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. For reasons both religious and artistic, this is among the most important and celebrated chapels in Christendom. Popes commissioned the decorations, usually by highly esteemed artists. Significant negative outcomes were less likely to be experienced here because the stakes were high, the patrons powerful, and the artists highly skilled. Yet here too risks abounded.

The original fresco altarpiece of the Sistine Chapel seemingly presented little risk. Commissioned in about 1481 by Pope Sixtus IV from Pietro Perugino, the subject closely corresponded to the fresco that Perugino had recently completed in the nearby church of St. Peter’s. The artist had an established track record even before he came to Rome, so the patron knew what he was getting. Yet, this same work also illustrates ignorance: Neither Sixtus IV nor Perugino could have imagined that only a few decades after the altarpiece was unveiled, Pope Paul III would have Michelangelo destroy it to make room for his new painting, the Last Judgment (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Michelangelo, The Last Judgment, 1534–41, fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

The Last Judgment, in turn, encountered significant production and reception risks. According to Reference Vasari and de VereVasari (1912–15, 6:185), Michelangelo’s friend Fra Sebastiano del Piombo persuaded the Pope that Michelangelo should paint the Last Judgment in oil on plaster, a new technique that Sebastiano himself developed. Michelangelo remained noncommittal, which should have alerted all to the risk of a negative outcome. Finally, Sebastiano prepared the wall for oil painting, then Michelangelo waited “some months without setting his hand to the work. But at last, after being pressed, he said that he would only do it in fresco,” and the “incrustation” applied by Sebastiano was removed. According to documents, this took place in 1536, and the Last Judgment was completed in 1541 (Reference MancinelliMancinelli, 1997: 160).

The stylistic and iconographic innovations in the fresco dramatically raised the possibility of reception risks. Shortly after the Sistine Chapel altar wall was unveiled, the secretary of Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga, Nino Sernini, wrote that there was “no lack of those who condemn it.” He noted one criticism shared by numerous contemporaries: Michelangelo “made Christ beardless and too young, and that he does not possess the appropriate majesty.” Fifty years later, in 1591, Gregorio Comanini wrote that the lack of a beard was considered by some to be an error because “theologians teach us that men have to be resurrected with beards and as mature as our Savior when he died” (Reference BarnesBarnes, 1998: 78, 100). These viewers and many others (Reference FreedmanFreedman, 2015: 24–5), it seems, neither understood nor appreciated Michelangelo’s innovative representation, which gave Christ the dignity of an ancient god. Significantly, Christ’s beard appears in several otherwise faithful copies of Michelangelo’s fresco dating from the sixteenth century (Reference AgostiAgosti, 1989: 1293). A few decades later, Pirro Ligorio attacked an unnamed painter, evidently Michelangelo in his Last Judgment, who represented overly muscular women, and who showed male and female figures, adults and children, and angels and devils in too similar a fashion (Reference SchreursSchreurs, 2000: 410; on “artistic innovation as a problem,” also see Reference Van Kesselvan Kessel, 2017: 96–103). This criticism explicitly attacked the artist’s skill. Indeed, the nudity of many saints in the Last Judgment spurred the best-known criticism of Michelangelo’s fresco. Dramatic consequences followed: Starting in 1564, two figures were repainted, and clothing was added to about forty more. The loss to Michelangelo’s original conception was minor relative to the greatest danger it faced. As we will see in Section 3, many of the criticisms related to reforms associated with the Council of Trent, and several Renaissance observers even recommended that the fresco be destroyed.

Renaissance Risk Assessment

In Renaissance Europe, the winds of fortune tossed people from all walks of life. Merchants and bankers, for example, frequently mentioned hazards in their writings, and struggled to limit those risks. Many understood the familiar principle already articulated in the fourteenth-century French proverb: “He who never undertook anything never achieved anything.” Every merchant who launched an undertaking or purchased goods to be resold later had to weigh benefits and costs, however informally. Are the odds that I can resell the goods for a significant markup great enough to justify the risk of buying and holding them? And, if so, how should the price reflect the risk that they may get stolen or damaged? The presence of risk was well understood; how to deal with it was much less so. Similarly, in the art world, risks abounded, and a venturesome approach was required to have prospects of success in any role.

In comparison to merchants and bankers today, those working in the Early Modern period faced at least three significant obstacles to confronting risk effectively. First, insurance calculations were primitive, as data sets were minuscule relative to those today for, say, life expectancy or shipping risks. Moreover, there is no evidence that Renaissance insurance rates were set based on anything close to statistical analyses. Even in today’s insurance world, lack of data leads to grave consequences, such as when Lloyds of London collapsed in the 1990s due to completely unforeseen levels of asbestos liability. Second, much of the information necessary to make decisions was based on inaccurate instruments, such as faulty compasses or discredited beliefs. If you do not understand weather systems or illnesses, it is difficult to create appropriate insurance policies. If you agree with the fifteenth-century architect Filarete that the stability of buildings is based not only on “the goodness of the material,” but also “the sign or planet under which it was built” (Reference Hub, Schraven and DelbekeHub, 2011: 23), you hire an astrologer to select the most auspicious time and date to begin construction. This method for reducing production risks was once common for major Renaissance buildings. Alas, believing in celestial charts for new buildings does not make them any more effective. Third, our modern tools for displaying information had not yet been invented. Only in 1620 did Michael Florent van Langren, a Dutch cartographer, create the first chart of statistical data, an innovation that allowed one to easily trace information points across time (Reference Friendly and WainerFriendly and Wainer, 2021). Without the line graph, bar chart, and pie chart to facilitate comparison, it is difficult to distill informative patterns from individual case histories.

Several additional factors made risks particularly hard to gauge in the Renaissance art world. First, paintings and sculptures varied greatly, far more than many other products in an age that long preceded mass standardization. One found greater variation among portraits than, say, among clocks or beds. Such variability reduced the value of experience in judging risks. Second, most people active in the art world made few purchases. Though the most esteemed buyers might acquire many works of art, these would typically include only one or two of a particular type, such as altarpieces, fresco cycles, or sculpted busts. Third, while artists often provided preliminary drawings of commissioned works, visits to artists’ studios were rare; hence, most patrons acquired finished products sight unseen. If patrons were displeased, their artists faced an increased risk of reduced payment, requests for changes, or even rejection. The confluence of these factors imposed further risks on participants in the art world: they were severely limited in their ability to assess the risks they faced. Even with today’s sophisticated risk-assessment tools, none of these factors can be analyzed statistically. Rather, individuals would have to assess them using subjective or personal probabilities. That concept was not even recognized until the twentieth century (Reference Ramsey, Ramsey and BraithwaiteRamsey, 1931).

The related field of behavioral decision theory first received significant attention in the 1970s.Footnote 4 Its principal finding is that individuals regularly make poor decisions, particularly when facing uncertainties. Now widely accepted, this conclusion contrasted sharply with the then-standard assumption in economics that people choose reasonably rationally. Similar shortcomings in decision-making were at play in the Renaissance period. Moreover, what we think of today as “modern science,” with its careful attention to painstaking observation and causal reasoning, had not been developed. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Galileo pioneered such methods, but his era hardly embraced him. Even research based on careful observation with telescopes was risky business in the Renaissance.

Certainly, all the participants in the Renaissance art world had to grapple with informal risk weightings. Some people were better at this than others. Most of the major patrons and collectors had succeeded in other realms where reasonably effective weighing of risks was critical to success. Those who failed or fell short in business rarely had the resources to commission or purchase art. Leaders in governments and churches, the most frequent patrons of major commissions in architecture, painting, and sculpture, often addressed risks in their regular activities, which gave them some training and insight. Moreover – and this important detail is often overlooked – elite patrons regularly engaged intermediaries with business experience and broad exposure to the business of art to advise them on or to handle their deals. The most fundamental requirement for limiting risk is to assess potential dangers with reasonable accuracy. For patrons, it is far more valuable to identify the artist who regularly delivers on time than to write a contract with a payment claw-back should a producer prove unreliable. That said, it was still valuable to introduce risk-limiting measures in these dealings, such as contracts, evaluating committees that ruled on whether payments should be reduced, and the use of preliminary drawings.

Some players capitalized effectively on their superior ability to calculate risks. Lucas Luce, for example, a dealer active in late sixteenth-century Amsterdam, purchased untitled and unattributed paintings at auction for low prices and then, working as an arbitrageur, resold them to new buyers (Reference MontiasMontias, 2002: 120). Luce prospered by taking on well-calculated risks. However, those dealers who calculated poorly, and there were many, met failure.

Artists too had to engage in informal risk weightings, say in deciding how much to charge. Ask for too much, and a commission or sale might be lost. If you work for a patron, you have timing risks: underestimate the time required for a project, and you run the risk of late delivery which will anger your patron. The production process itself included countless assessments of risk and the decisions that followed. Attempt innovation in style or technique? Pay the price for the highest quality materials – and whom to trust when buying materials? How much work to delegate to assistants, given the threat that poses to quality? Make the wrong decisions and time, money, and status could be lost.

Mistakes in taking risks are of two main types: taking risks that one shouldn’t, and not taking risks that one should. Of the two, it is far more difficult to document risks mistakenly foregone. But we do have an example where too much and too little reception risk was taken by the same artist. Fra Bartolomeo, a Florentine painter usually associated with conventional representations of religious subjects, traveled in 1508 to Venice and signed a contract with Bartolomeo d’Alzano, prior of San Pietro Martire, for an altarpiece depicting the marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena. The artist and patron probably agreed on the highly unusual iconography of the painting, completed just a year later. By this time, however, the prior had already died, and his successor evidently did not like the work. He refused to pay Fra Bartolomeo, then commissioned a less expensive and very conventional painting by a minor local painter, Francesco Bissolo. In the end, Fra Bartolomeo donated the rejected altarpiece to a friend and prior in Lucca, who installed the work in the church of San Romano (Reference EkserdjianEkserdjian, 2021: 40; Reference NovaNova, 2021: 9–10). Perhaps this stinging experience prompted Fra Bartolomeo to play it too safe that same year when he produced what must have been a rather conventional Madonna for Averardo Salviati. A 1509 letter from the patron indicates that he objected on aesthetic grounds. He was displeased because the work is very ordinary and “new things are always more beautiful”; the work was returned (D. Reference FranklinFranklin, 2001: 94).

In the Renaissance art world, uncertain outcomes could prove a blessing or a blow. This volume focuses on the latter. It recounts a litany of the losses that participants in the art world suffered, from paintings purloined to statues scorned.

2 Production Risks: Sources and Their Control

Many cultural products elicit fascination in process; witness the popularity of “backstage” videos about the creation of films or albums. In textbooks and popular publications, interest in Renaissance art focuses on the finished product. Over the last half-century, however, many Renaissance art historians have turned their attention to the complex networks of individuals and processes involved in the creation of paintings and sculptures. A recent study elucidates how broad that network was. In the later sixteenth century, the cost of sending the king of Spain a marble statue from Florence included payment

for the procurement of marble, for the sculptor to make it, for it to be properly packaged, for it to be delivered to a seaport, for it to be loaded onto a galley or other vessel, for the shipment by sea, for the oxen, carts, and men to transport it to Madrid, for passports and customs fees, and for the labor, meals, and sometimes clothing for the workers who accompanied the sculpture, delivered it to the court, and set it into place.

Production networks produce extraordinary results when information and materials pass reliably from node to node, as happens in most parts of contemporary economies. The production of art in the Renaissance faced a range of reliability problems, from miscommunication and misrepresentation to subcontracting and sunken ships. This section surveys the various mishaps that could and did occur from the artist’s conception of a work to its final placement. Scores of documented examples show that people in the Renaissance knew about production risks for art and made decisions aimed to mitigate them.

Trust was a major mitigating measure. The concept of trust, often discussed by economists and sociologists, but much less by art historians, is a key instrument for bringing otherwise insurmountable production risks down to an acceptable level. In his Foundations of Social Theory, James Coleman argued that the incorporation of risk into decision-making “can be described by the single word ‘trust.’ Situations involving trust constitute a subclass of those involving risk. They are situations in which the risk one takes depends on the performance of another actor” (Reference ColemanColeman, 1990: 101). In other risky situations, nature is the prime actor.

The success of the Renaissance art market derived in no small part from the spread of trust among its participants: artists and patrons, buyers, dealers, and suppliers. Spreading trust in this setting reflected, capitalized on, and supported faith in a broad array of Renaissance institutions. But why did trust exist given the widespread losses discussed in these pages, many due to the misbehavior of individuals, and the multitude of losses not even mentioned? The reason is that it is often a reasonable strategy to trust an individual who may turn out not to merit trust, that is, who turns out not to be trustworthy. Any dealings with an individual, today as in the Renaissance, involves some element of a gamble. Reputations and legal remedies – both intended to deter bad behavior – are helpful in shifting the odds in a strongly favorable direction. However, even if losses remained a real possibility, a transaction should go forward if the potential gains outweigh the risk of losses.

Renaissance societies experienced high levels of transactions for many things, such as sales of cloth and insurance policies, with individuals and firms on both sides of the market. These transactions, which yielded information about the reliability of participants, made it important for participants to protect their reputations. “Strong ties” typically existed among close relatives or between merchants and repeat buyers, such as artists and repeat patrons. If participants in a transaction knew one another, perhaps from a few low-value business transactions or from a distant family relationship, they had what specialists call a “weak tie.” A single tie was not nearly sufficient to generate trust. In his study of “What a Merchant’s Errant Son Can Teach Us about the Dynamics of Trust,” Ricardo Court examined a series of letters sent in the mid-sixteenth century by a Genoese merchant, Giovanni Francesco di Negro. In one, he wrote, “I urge and implore you not to put much of your money in the hands of strangers and less in those in whom you do not have faith, because as you can see every hour there are new bankruptcies” (Reference Court, Biorci and CourtCourt, 2014: 106). Given that merchant ledgers remained secret, the solvency of a business remained a mystery, and trust took on great importance. For that reason, di Negro wrote, “I am pleased that you persist in the service of those gentlemen to their satisfaction because getting good experience in that business will [earn] you honor and profit” (Reference Court, Biorci and CourtCourt, 2014: 92). In modern terms, the trust established by strong ties facilitated future transactions.

If participants with weak ties were embedded in a network of ties, and if their networks overlapped significantly – perhaps due to family connections, common friends, geographic proximity, or related commercial activities – then this crisscrossing of engagement and information flow could create levels of trust as powerful as strong ties (Reference GranovetterGranovetter, 1973). That crisscross was the norm for transactions conducted in a city the size of Florence, and certainly in smaller ones. There were few degrees of separation between wealthy and less successful members of the same extended family (Reference Herlihy and Klapisch-ZuberHerlihy and Klapisch-Zuber, 1985). In Italy, and especially in Tuscany, numerous scholars have focused on the many ties that bind kin, friends, and neighbors.Footnote 5 Naturally, this weave of trust extended into the art world, at least for most patrons. In contrast, when Italian non-elites, often shopkeepers and peasants, left provisions for art commissions in their last wills and testaments, typically decorations for a church, convent, or hospital, they almost never mentioned specific artists (Reference CohnCohn, 2021: 43). Most probably, their circle of kin, friends, and neighbors did not include many painters. Instead, non-elites put their trust in the ecclesiastical institutions that were obliged to fulfill the legal obligations of wills to commission works of art.

Strong ties facilitated some of the most famed transactions for commissioned art. However, weak ties played a facilitating role in many Renaissance art transactions when strong ties did not exist between critical parties. The prime requirement was that sufficient information flowed about past performance to shape future expectations about adequate performance. “Reputational externalities,” a new concept to scholars, added to weak ties and overlapping networks to foster information flow. Reputational externalities describe how trust travels across a group of individuals who possess similar characteristics.Footnote 6 For example, good experience with one doctor, one cloth merchant, or one artist will lead you to think more highly of others in these professions, and conversely with a bad experience. If patrons learned in general that artists were tardy, they would expect their artists to be tardy. The information from reputational externalities is less reliable than the information from direct experience. Nevertheless, it is important because it is much more abundant. And when the uniting characteristic between individuals is membership in a selective organization, such as an artists’ guild, then the reputational information is much stronger. As we will see in Section 5, such organizations have powerful motivations to demand high quality among their members.

In the absence of strong ties, three elements enabled extensive communication flows: weak ties, significant network overlap, and reputational externalities. These flows were one of the three components that enabled art transactions to go forward. Trust and social capital were the other two components. Trust was basically the expectation that each party to a transaction would behave as if a firm, enforceable contract had been signed, and performance was readily monitored. Thus, artists would not pass off excessive work to assistants, dealers would accurately describe a work, and patrons or buyers would not chisel on an agreed payment.

Social capital refers to the benefits a society, or a group within it, gains from the network of relationships that promote shared values, trust, and cooperation. Tighter groups usually enjoy more social capital. In an innovative analysis of the Brancacci Chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Nicholas Eckstein explores the formal and informal bonds of community among fifteenth-century artists and their clients (Reference EcksteinEckstein, 2010). He focuses on one Florentine neighborhood and the levels of cooperation within it. The lesson, however, is general: social capital greased the wheels of the art business across Renaissance Europe. The term social capital was first defined a century ago, and the concept has since been elaborated and debated by numerous distinguished scholars, including sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and James Coleman, political scientist Robert Putnam, and urbanist Jane Jacobs (Reference Eckstein and NicholasEckstein and Terpstra, 2010).

Our trio of concepts – extensive communication flows, trust, and social capital – are strongly interlinked. Each reinforced the other in a virtuous triangle, as shown by the arrows flying in both directions in Figure 5. The arrows – dotted from extensive communication flows, dashed from social capital, and dot-dashed from trust – represent these bolstering forces. Triangles constitute the strongest shape. However, if the sides are not sturdy and secure, a transaction will be risky. One, or conceivably both, parties can get hurt. The flying arrows sometimes miss their target. When they do, trust may be lost; reliability may be diminished. Errant arrows enable the risks that produce the litany of losses described in this volume. In the Renaissance art world, this three-component triangle created a reasonably sturdy structure for taming risk. Thus, a significant division of labor was enabled, which in turn provided a broad array of goods on an efficient basis. The widespread production and sale of skilled artworks certainly required both a division of labor and significant risk taming.

Figure 5 Enabling trust.

As we indicate throughout this volume, commissioned art presented more transaction risk than most goods. There were frequent delays between initiating and completing a transaction. The product was almost always individualized, implying that information flows along networks would be less informative. There were significant concerns for quality and dignity. Finally, a buyer might chisel, and a completed work oriented to a patron, such as a portrait or an altarpiece depicting unusual saints, could be very hard to resell. All these characteristics magnified risks.

The major benefit of trust was risk reduction. It made a negative outcome from purchasing or commissioning a work less likely. Thus, given trust, those who wanted or needed paintings and sculptures were much more willing to purchase or commission them. As the art world grew in volume and geographic spread, patrons and buyers turned increasingly to artists, dealers, and other intermediaries they did not know well. Many came from different cities, regions, or countries. Already in the eleventh century, as discussed in a study widely cited by economists, reputations played a major role in the coalitions of Maghribi traders around the Mediterranean (Reference GreifGreif, 1989).

Such distant transactions raised the potential for negative outcomes, as Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici in Florence learned in 1588. He commissioned a bronze frame for the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Unfortunately, when the expensive gift arrived in this distant land, it turned out to be too small (Reference RonenRonen, 1970: 432). Artists creating custom-made works for distant settings had to trust intermediaries for essential information such as measurements. When that trust proved misplaced, disaster ensued. Sometimes, this failure of trust resulted from incompetence; in other cases, someone violated trust to obtain an advantage. Trust could only reduce risks; it could not eliminate them. Participants in the international art world found these trust-trimmed risks acceptable given the accompanying benefits. Alternatives were often few or nonexistent. For example, commissions remained the only way to obtain a portrait, and, for most Italian artists through the sixteenth century, patronage provided the sole means to sell major paintings and sculptures.

Anthony Pym’s “Translating as Risk Management” (Reference Pym2015) provides a rare study that applies risk analysis to cultural productions. Two of his categories aptly apply to Renaissance art. “Communicative risk” refers to the way texts are interpreted and used in contexts. Much as a translator might misunderstand the meaning or nuance of a source text, artists might misconstrue a patron’s request or misinterpret the story the patron selected for representation. The less one understands the culture that produced a source text, the greater the risk of mistranslation. If, say, a patron asks a local artist to produce a scene that is standard for their society, the communicative risks are low. For this reason, most Renaissance contracts for art specified little about the subject beyond the most basic description, such as a list of figures to represent, or a popular narrative, such as the Annunciation. Communicative risks increase when artists are requested to depict unusual subjects or obscure individuals. In those cases, contracts often provide details (Reference GilbertGilbert, 1998). For example, sculptures made north of the Alps often depict the dead Christ in the lap of his mother, but this subject was much less common in Italy. Thus, when a French cardinal commissioned Michelangelo to depict a marble version for his tomb in the basilica of St. Peter’s Rome, he included a definition of the term “pietà.” For this work, the patron (or his intermediaries) did communicate with the artist and, we assume, approved preliminary plans.

In his article, Pym also refers to a “credibility risk,” which might be considered less than full trust between key players involved in a translation or in the final product itself. Andrea Rizzi, Birgit Lang, and Pym develop the credibility risk concept in their book, What Is Translation History? A Trust-Based Approach (Reference Rizzi, Lang and Pym2019). Among potential risks, they consider how “publishers and clients lose money from poorly performed and produced translations … Translators also risk their reputations every time they accept a job. From the perspective of the end user, clients accept the risk that the texts they paid for may not be reliable” (Reference Rizzi, Lang and PymRizzi, Lang, and Pym, 2019: 12). Change the subject of the sentence to Renaissance art, and the passage applies directly. So too does the authors’ sustained consideration of how the translator might (dis)trust the patron or client, and vice versa.

In an influential article, Luhmann states that “trust is a solution to a specific problem of risk” (Reference Luhmann and GambettaLuhmann, 1988: 95). He discusses how the very appearance of the term “risk” in the early modern period indicates the possibility of unexpected and undesirable results flowing from a decision. Thus, you have the option of commissioning a painting from a little-known artist, today’s equivalent of buying a used car. In either case, you might be dissatisfied. “If you choose one action in preference to others in spite of the possibility of being disappointed by the action of others, you define the situation as one of trust” (Reference Luhmann and GambettaLuhmann, 1988: 97). In sixteenth-century Italy, when international and transcontinental commerce constituted a significant portion of the economy, “correspondents were frequently far distant and beyond surveillance. As a result, interpersonal trust became fundamental to the operation of the Renaissance economy” (Reference BakerBaker, 2021: 74).

Misrepresentation and Materials

Deliberate misrepresentation sits at the apex of credibility risk in the world of Renaissance art. Many accounts document the falsification of ancient works, which were far more expensive than modern ones (Reference KurzKurz, 1948). In the late sixteenth century, both Vasari and Van Mander wrote as well about forgeries of contemporary art, specifically engravings that imitated works by Albrecht Dürer. The production and sale of these works undermined trust; their existence imposed a range of risks for the buyers, forgers, and the original artist. Dürer even wrote at the end of his woodcut series of The Life of the Virgin: “Woe to you! You thieves and imitators of other people’s labor and talents” (Reference KurzKurz, 1948: 106). For Dürer, the most famous of Germany’s artists, forgeries created a credibility risk. Buyers beware!

The repercussions of forgeries stretched far. Reference Van Mander and MiedemaVan Mander (1994: 301) recounts that Hans Bol decided “to abandon canvas painting entirely when he saw that his canvases were bought and copied on a large scale and sold as if they were his. In turn, he devoted himself totally to painting landscapes and small histories in miniature saying: ‘Now let them labor in vain trying to copy me in this.’” Bol’s contemporaries interpreted his decision to make miniatures, some still extant, as his response to the unusual production risk of fraudulent imitation by others.

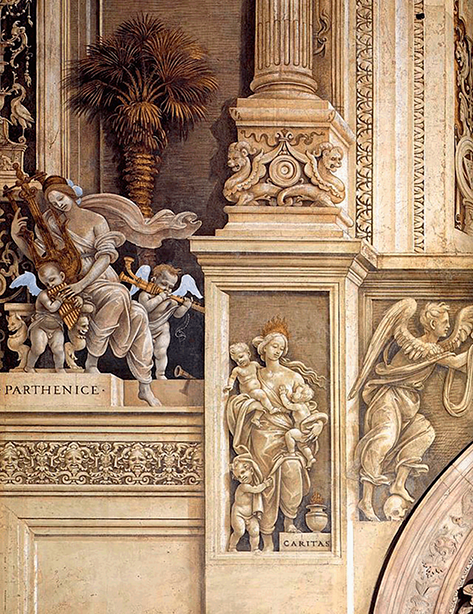

Far more often, patrons and buyers obtained works presented as creations by the master artist but created in part by his workshop. This standard procedure served to both save time and train apprentices. Naturally, this led to a range in quality, as surviving documents make clear. Pantoja de la Cruz, the principal portrait artist at the Spanish court at the turn of the sixteenth century, received 4,000 reals for one painting of Queen Margaret of Austria but only 100 for another. The first was a gift for the king of England; the second, presumably by the workshop, was for a nobleman (Reference Falomir, Marchi and Van MiegroetFalomir, 2006: 140). Sometimes, paintings or sculptures were made entirely by the workshop but passed off as a product of the master. When such misrepresentations were detected, patrons typically withheld payment, often with the support of the legal system. For example, soon after Elisabetta Aldobrandini commissioned an altarpiece from Domenico Ghirlandaio, the artist died in 1493 (Figure 6). The patron, dissatisfied with the completed piece, refused to make the final payment. The case went to court. Remarkably, we have the report of the arbitrator; he cited expert opinions that the painting was carried out poorly by students less skilled than the master. Not surprisingly, the court sided with the patron (Reference Nelson and ZeckhauserNelson and Zeckhauser, 2021: 19–20). In a similar vein, the town council of Brescia objected in 1568 that one of the ceiling canvases they had commissioned from Titian was not painted by him and refused to pay the full amount (Reference Piazza and FrangiPiazza, 2018). In both cases, the patron trusted the artist to produce a work largely “by his own hand,” a legal formula included in many contracts. According to Reference Vasari and de VereVasari (1912–15, 5: 153), Perino del Vaga received a commission to paint frescoes in the palace of the ruling Doria family in Genoa but had some of the work carried out by Pordenone. When Prince Andrea detected the difference between the two parts, he fired Perino and hired a third painter, Domenico Beccafumi. Most objections to excessive workshop assistance or subcontracting arose from dissatisfaction with the quality of the finished work. We can consider the negative outcome to be a blend of production and reception risk. Several examples get attention in Section 3.

Figure 6 Domenico Ghirlandaio and workshop, Rimini altarpiece, 1493–96, tempera and oil on panel, Museo della Città “L. Tonini,” Rimini.

Misrepresentations of materials represent a credibility risk of a different type. Across Europe, contracts and guild regulations regularly specified the required quality of both pigments and metals, especially gold and silver (Reference Kirby, Neher and ShepherdKirby, 2000). These documents prohibit substituting a poorer quality material for a better one. Patrons, buyers, and reputable artists undoubtedly feared that all that glittered was not gold. Technical analysis confirms that Gentile da Fabriano mixed various impurities into the gold he used for his Valle Romita polyptych, and this is probably true for many other works (Reference McCall and KovesiMcCall, 2018: 260).

In some cases, at least, the use of “impure” materials represented more misunderstandings between patrons and artists, rather than misrepresentations. Wealthy patrons – often having little technical expertise – wanted the most illustrious and expensive materials used. Artists, having technical knowledge, would have known how to properly mix and manipulate materials for the best effect, but not necessarily requiring the highest quality or cost of materials.Footnote 7 But deception could pay, and artists and merchants did take advantage. In the mid-sixteenth century, when collectors across Europe looked for examples of feather mosaics produced in modern-day Mexico, they were at risk of receiving fakes. They could have read in Bernardino de Sahagun’s Florentine codex about the “fraudulent embellisher of feathers” who “sells old, worn feathers, damaged feathers; he dyes those which are faded, dirty, yellow, darkened, smoked” (Reference Russo, Wolf and ConnorsRusso, 2011: 392).

A step beyond fraud was filching. Patrons had to be on guard against the theft of materials, and precious ones were particularly at risk. In Rome, Pope Paul V gave the nobleman Pier Vincenzo Strozzi responsibility to oversee the renovation of the Cappella Paolina in the church Santa Maria Maggiore. Strozzi, it seems, stole some lapis lazuli purchased for that project. He then gave it to the artist Antonio Tempesta and commissioned him to use it in another painting, Pearl Fishing unrelated to the chapel (Figure 7) (Reference Nygren, Jacobi and ZolliNygren, 2021: 136). Every link in the supply chain required trust. Thus, artists and artisans had to trust the merchants who sold them materials. Few tests seeking to distinguish most true jewels, metals, and pigments from cheaper imitations were reliable. Hence, purchasers had to rely on their eyes and especially the reputations of the sellers. Some materials presented particular risks to artists, quite apart from intentional misrepresentation. Large blocks of marble, for example, often contained flaws or long colored lines, known as veins, made by deposits of crystalized minerals. When carving a Standing Christ in white marble, Michelangelo discovered a black vein. As a result, he had to abandon the block and start a second version. Costs for the piece escalated, as did delays (Reference Carlson and GamberiniCarlson, 2021).

Figure 7 Antonio Tempesta, Pearl Fishing, ca. 1610, oil on lapis lazuli, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Patrons and buyers relied on and trusted artists to use the soundest practices when securing, using, or shipping materials and works. Reliance sometimes failed, perhaps to save costs, but ignorance or sloppiness also contributed. In a letter, King Philip II of Spain complained because a very visible crease disfigured Titian’s Venus and Adonis (Madrid; Figure 8). The canvas painting had been folded for shipping, but the safe practice was to roll it on a pole. According to Vasari, Perugino did not use oil paint properly. As a result, some of his paintings “have suffered considerably, and they are all cracked in the dark parts” (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 5: 38). In a similar vein, Reference Van Mander and MiedemaVan Mander (1994: 289) wrote that before painting a large canvas, Pieter Pourbus “had primed it too thickly with a glue ground.” Moreover, that particular work “was frequently rolled up and rolled out, and so it cracked and flaked off in many places.” Michelangelo’s lack of skill in bronze casting undermined his first attempt to create a statue of Julius II for the church of San Petronio in Bologna (Reference HendlerHendler, 2021). His second casting proved successful, but the piece suffered a different fate. Just a few years later, a revolution in Bologna overthrew the ruling Bentivoglio family, and the bronze sculpture was melted down. The risk of this dramatic outcome was enhanced because the sculpture’s material was expensive and easily recyclable.

Figure 8 Titian, Venus and Adonis, 1554, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Repurposed bronze for a new statue brought production risks to an artist. It was impossible to determine the precise combination of metals used to create the bronze. This introduced a wide array of unknowns, including the melting point, porosity, and fracture of the metal, catalysts for catastrophe in the finicky chemistry of casting.

Financial Risks

When artists produced quality works, they trusted patrons to pay them the agreed sum. This compensation was often stipulated in registered contracts for altarpieces and fresco cycles. For other works, payment was usually the subject of private agreements. On very rare occasions, a stingy patron could be taken to court, as happened with Elisabetta Aldobrandini, though she won the case. But artists had other weapons for extracting payment or taking revenge on short-changing patrons, as we learn from Van Mander and Vasari. Their well-known publications alerted readers to the financial risks faced by artists. Van Mander recounts two amusing tales, perhaps fabricated, about Flemish painters working for foreigners. The first concerns the portrait of an English captain by Jacques de Poindre (or Jacob de Punder). The captain, Pieter Andries, abandoned the work without paying. De Punder reputedly added “bars in watercolor in front of the face so that it appeared as though the captain was in prison and put it on display” (Reference Van Mander and MiedemaVan Mander, 1994: 187). In a similar vein, Gillis Mostaert painted an image of the Virgin for a Spaniard, but when he did not receive adequate compensation “he covered it with an undercoat of chalk and glue on which he painted Mary wildly decked-out and as flippant as a whore” (Reference Van Mander and MiedemaVan Mander, 1994: 302). In the end, both painters got paid and removed the offending additions. Vasari tells more plausible stories about artists who refused to consign works for payment considered insufficient, such as Tribolo’s sculpted angel for the Pisa Cathedral (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 7:7). Sodoma, we read, did not complete a painting cycle in Siena in part because of his own “caprice, and partly because he had not been paid” (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 7: 254). When Michelangelo sent Angelo Doni his painting of the Holy Family (Florence; Figure 9), he requested the reasonable compensation of 70 ducats. The miserly merchant tried to pay merely 40. Offended, the artist reputedly demanded and received double the original price (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 9: 19).

Figure 9 Michelangelo, Doni Tondo, 1505–1506, tempera grassa on panel, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.

In three dramatic passages, Vasari recounts how the sculptors Donatello, Pietro Torrigiani, and Matteo dal Nassaro took the extreme step of destroying their work rather than selling it for less than it was worth (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 2: 245; 4:187; 5:377). More often, we can assume, an “underpaid” artist tried to sell his work to someone who would pay more, as did the painter Bartholomeus Spranger (Reference Van Mander and MiedemaVan Mander, 1994: 341). Naturally, the new owner might have different needs. Thus, when Francesco Torbido failed to receive payment for a portrait of a Venetian gentleman, “he had the Venetian dress changed into that of a shepherd” and recycled the painting to a certain Monsignor de Martini (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 6: 25). Who knows how many commissioned works changed appearance or owners because artists found ways to mitigate their most important production risk? In addition, an artist’s potential refusal to sell was a threat that helped deter patrons who might otherwise haggle about the price.

Some disputes ultimately led to happier endings. Andrea del Sarto’s celebrated fresco cycle depicting the Life of San Filippo (Figure 10), for the Florentine church of the Santissima Annunziata, was one. With reduced compensation offered, the painter refused to finish the cycle. The patron “would not release him from his bond without Andrea first promising that he would paint two other scenes, at his own leisure and convenience.” In the end, the artist received “an increase of payment, and thus they came to terms” (Reference Vasari and de VereVasari, 1912–15, 5: 90).

Figure 10 Andrea del Sarto, Death of Saint Philip Benizi and Resurrection of a Child, 1510, fresco, Santissima Annunziata, Florence.

Trust was at the center of the Renaissance art business, but many untrustworthy participants operated at the periphery. Thus, some patrons underpaid. Some artists created substandard works. Some outlier artists even engaged in nefarious financial practices. In 1596, the Art Academy of Rome took action. For example, it established regulations to prohibit artists from underbidding for a commission already entrusted to another. In 1607, the Academy introduced penalties for artists who obtained a commission with a low bid and then increased the price as the work progressed (Reference CavazziniCavazzini, 2008: 168–9). To justify these new rules, both activities must have been widespread in Rome and presumably elsewhere.

Naturally, many types of financial risks emerged that did not involve trust. As Larry Silver discusses in Section 4, open markets, first in Antwerp and then across Europe, encouraged artists to specialize in genre paintings. When the fashion for these dimmed, prices fell. Many players beyond the artists themselves needed to predict the movement of the marketplace. A series of letters from 1665 evinces how Balthasar Moretus II, an important Belgian printer and publisher, dealt with financial risks in the ornate book trade. If Cornelis de Wael, an artist and dealer, wanted to undertake sales at his own risk, he would receive a 25 percent discount on the price plus a 5 percent commission; alternatively, the publisher would assume the risk but offer no discount and a lower commission (Reference StoesserStoesser, 2018: 71).

Delivery Risks

The most frequent risk for art commissions was delay or non-completion. Numerous accounts report patrons frustrated over delays. Francesco del Giocondo never received the portrait he commissioned of his wife, (Mona) Lisa, which wound up in the hands of French king François I. Worse yet, perhaps, Leonardo and his workshop made nude variations of the painting (Reference Nelson and ZeckhauserNelson and Zeckhauser, 2021). In his discussion of Parmigianino’s frescoes in the church of the Steccata, Parma, Vasari (5: 251–2) wrote that the artist began to “carry it on so slowly that it was evident that he was not in earnest … the Company of the Steccata, perceiving that he had completely abandoned the work … brought a suit against him.” Surviving records confirm that Parmigianino worked on frescoes in the Steccata (Figure 11) on and off between 1533 and 1539 (Reference EkserdjianEkserdjian, 2006: 10). He never completed the cycle.

Figure 11 Parmigianino, Three Foolish Virgins (detail), 1530s, fresco, Santa Maria della Steccata, Parma.

In 1478, the Augustinian canons at the convent of San Donato a Scopeto, just outside the walls of Florence, took a calculated risk when they commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to paint the Adoration of the Magi for the high altar. He had never produced a large-scale painting for anyone, though the painter had received a commission for an altarpiece in the town hall. Nevertheless, Leonardo was the son of a notary who often worked for the convent; that boosted confidence for the patrons. Ultimately, the canons stipulated a contract with Leonardo that addressed their concerns about delay or non-completion (Reference BambachBambach, 2019, 1:242–43). The canons hedged their bets through both requirements and financial arrangements. To begin with, Leonardo had to work on the commission for four months before the patron made a formal agreement. During this time, most probably, the artist had to provide finished drawings, or perhaps even the underpaint, still visible on the wooden panel today. Two additional clauses in the contract were designed to encourage Leonardo to complete the work within the stipulated two-year period. The artist would have to pay for all his materials, and he would lose all rights to the panel if it remained unfinished. These risk-reducing arrangements proved insufficient. Leonardo departed Florence for better opportunities in Milan in 1482, leaving the altarpiece started but never completed.

Contract provisions that incorporated punishments for delays were one tool to help patrons avoid tardy deliveries. Advisors, who informed patrons about artistic quality, were a second. Letters from 1663 to Don Antonio Ruffo, Prince of Scaletta, indicate that Cornelis de Wael warned him against ordering a painting by Claude Lorrain, a slow worker, or from Nicolas Poussin, as he was too frail (Reference StoesserStoesser, 2018: 82). This rare documentation provides insight into the advisory roles intermediaries played between countless patrons and artists. “Rather than being a ‘two-way’ street, the process of art patronage,” as Sheryl Reiss noted, “was, in fact, a complicated ‘multi-lane highway’, often involving intermediaries” (Reference Reiss, Bohn and SaslowReiss, 2013: 26). These middlemen often served to reduce the risk of disappointment for patrons.

A few major Renaissance artists often left commissions unfinished, but what did their contemporaries make of this behavior? We find some clues in the short biographies of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and others written by the humanist Paolo Giovio in about 1525 (Reference Nelson and ZeckhauserNelson and Zeckhauser, 2018). Giovio observed that Leonardo completed very few of the many commissions he received. He was unstable in character and readily lost interest in his works. This assessment would sour the enthusiasm of many a potential patron. Michelangelo proved even less reliable than Leonardo. Giovio noted that Michelangelo was commissioned to build the tomb of Pope Julius II and, having received many thousands of gold florins, he made several very large statues. What Giovio left unsaid – but what everyone in Rome knew – was that the tomb, two decades after its commission, remained unfinished. It was later completed, with major sections carried out by assistants, including the recumbent image of the pope himself. Even the most famous artists could be unreliable, some frequently so, and yet, despite the significant risks, major commissions still came their way. Patrons felt the risks were worth it given that the upside was art by the biggest names of the day.