Book contents

- Water Justice

- Reviews

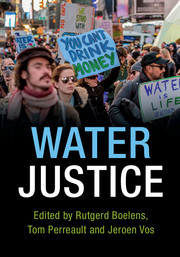

- Water Justice

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Introduction: The Multiple Challenges and Layers of Water Justice Struggles

- Part I Re-Politicizing Water Allocation

- Part II Hydrosocial De-Patterning and Re-Composition

- Part III Exclusion and Struggles for Co-Decision

- Part IV Governmentality, Discourses and Struggles over Imaginaries and Water Knowledge

- Introduction: Governmentality, Discourses and Struggles over Imaginaries and Water Knowledge

- 15 Neoliberal Water Governmentalities, Virtual Water Trade, and Contestations

- 16 Critical Ecosystem Infrastructure?

- 17 The Meaning of Mining, the Memory of Water

- 18 New Spaces for Water Justice?

- 19 Conclusions: Struggles for Justice in a Changing Water World

- Index

- References

15 - Neoliberal Water Governmentalities, Virtual Water Trade, and Contestations

from Part IV - Governmentality, Discourses and Struggles over Imaginaries and Water Knowledge

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 February 2018

- Water Justice

- Reviews

- Water Justice

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Introduction: The Multiple Challenges and Layers of Water Justice Struggles

- Part I Re-Politicizing Water Allocation

- Part II Hydrosocial De-Patterning and Re-Composition

- Part III Exclusion and Struggles for Co-Decision

- Part IV Governmentality, Discourses and Struggles over Imaginaries and Water Knowledge

- Introduction: Governmentality, Discourses and Struggles over Imaginaries and Water Knowledge

- 15 Neoliberal Water Governmentalities, Virtual Water Trade, and Contestations

- 16 Critical Ecosystem Infrastructure?

- 17 The Meaning of Mining, the Memory of Water

- 18 New Spaces for Water Justice?

- 19 Conclusions: Struggles for Justice in a Changing Water World

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Water Justice , pp. 283 - 301Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018

References

- 15

- Cited by