4.1 Forests, Governance, and Rights in Tanzania

Forests make up 38 percent of Tanzania’s land mass and represent 46 percent of the total forested area in all of East Africa.Footnote 604 Although the majority of Tanzania’s forest area comprises dry woodlands, it also includes other forest types such as humid mangrove forests and coastal woodlands that are rich in biodiversity.Footnote 605 The forestry sector itself is not an important source of economic activity and timber products only amount to 1.9 percent of Tanzania’s GDP.Footnote 606 On the other hand, Tanzania’s forests provide important habitats and wilderness areas for a range of animal species, help maintain soil fertility, limit soil erosion, landslides, and floods, and regulate water catchments and quality.Footnote 607 These ecosystem services are essential for other important economic sectors, such as agriculture and tourism, and have been estimated to account for 10 to 15 percent of Tanzania’s GDP.Footnote 608 Forests are moreover critical to the livelihoods and cultural practices of rural and forest-dependent communities, who depend on them for shelter, income, food, building materials, traditional medicines, and energy supply (in the form of charcoal and fuel wood).Footnote 609 As a result, the forestry sector has long been at the heart of Tanzania’s development policiesFootnote 610 as well as the aid programs delivered by international donors.Footnote 611 Likewise, Tanzania’s policy framework for forest governance recognizes the importance of forests in the alleviation of poverty and the pursuit of sustainable economic growth and development.Footnote 612

Tanzania’s vast forests have been characterized by high and unsustainable rates of deforestation and forest degradation in recent decades.Footnote 613 Between 2005 and 2010, Tanzania lost 403,000 hectares of forest cover per year, corresponding to an annual loss of 1.16 percent of its total forest areaFootnote 614 and generating 122.14 million tons of carbon emissions on an annual basis.Footnote 615 Given its relatively undeveloped rural economy, its reliance on agriculture, and the limited commercial potential of its dry woodland forests, the main causes of deforestation and forest degradation in Tanzania have been local in nature and have included the conversion of lands for agriculture, bio-fuel production, and human settlements; livestock grazing; firewood and charcoal production; uncontrolled wild fires; illegal logging and mining; and infrastructure development.Footnote 616 The broader drivers of forest loss in Tanzania include the limited capacities of its government agencies to effectively manage forests and prevent the overexploitation of forest products and resources; its rapid population growth and the related environmental pressures that this creates; and the high levels of poverty among rural communities who depend on forests to meet their basic needs in terms of income, food, and energy.Footnote 617 That said, forests managed by rural communities under Tanzania’s advanced regime for participatory forest management have been characterized by lower rates of forest loss, as compared to forests managed by central authorities or those with an open-access status.Footnote 618 Given that the forests under the direct management of communities only amount to 13 percent of Tanzania’s total forest area, the provision of funding and capacity-building to support communities in securing and governing forests has thus long been identified as a promising intervention for reducing deforestation in Tanzania.Footnote 619

The management of land and forests was heavily centralized in TanzaniaFootnote 620 during British colonial rule with the adoption of laws and policies that prioritized the statutory rights of colonial settlers over the customary rights accorded to TanzaniansFootnote 621 and asserted control over forests, wildlife, and natural resources by establishing protected areas from which rural and forest-dependent communities were evicted and barred entry.Footnote 622 For the first few decades after independence, the authoritarian socialist regime of Julius Nyerere pursued a similarly coercive approach to land and resource governance. It expanded the number and scope of protected areasFootnote 623 as well as implemented a policy of large-scale villagization (ujaama vijijini) that involved the forcible resettlement and concentration of rural Tanzanians into planned villages and the establishment of agricultural cooperatives.Footnote 624 While this program gave newly formed village settlements the authority to manage land and allocate rights of occupancy within their borders, villagers themselves lacked statutory rights to land and enjoyed very little security of tenure as a result.Footnote 625 The resulting ambiguities around unclear and overlapping land rights, the lack of recognition of customary land rights and practices, and ongoing tensions over the management of natural resources and the exclusion of rural communities from forest and nature reserves generated a series of protracted conflicts over land between various actors of Tanzanian society.Footnote 626

In the second half of the 1980s, in response to an economic crisis and the pressures exerted through the structural adjustment programs imposed by multilateral donors, Tanzania began to transition away from socialist policies to adopt liberal economic policies and forms of governance.Footnote 627 This broader trend toward political decentralization coincided with greater interest among donors as well as Tanzanian officials in experimenting with community-based approaches to forest management in the early 1990s.Footnote 628 Finally, the extensive discontent with land conflicts and tenure insecurity led the reformist government of Ali Hassan Mwinyi to appoint a commission of inquiry on land matters.Footnote 629 These efforts eventually culminated in the adoption of three laws, the Land Act and the Village Land Act in 1999 and the Forest Act in 2002, which provide the foundations for rural communities to govern their lands and manage their forests in contemporary Tanzania.

The Land Act provides that all land is held in trust by the President on behalf of all citizensFootnote 630 and recognizes three categories of land: reserved land, village land, and general land.Footnote 631 Reserved land is land that is set aside by the central government for the purposes of conservation or development under national laws and ordinances, such as national parks, land for public utilities, and wildlife reserves.Footnote 632 Village land is land managed by Village Councils on behalf of Village Assemblies that falls within the demarcated boundaries of villages that have obtained formal certificates for this purpose as well as land that villages have been occupying or using for twelve or more years under customary law.Footnote 633 Village Councils may further demarcate village land into three sub-categories: communal land jointly used by villagers (such as pastures or forests); occupied land used and managed by individuals or groups; and future land set aside for future use by villagers.Footnote 634 Villagers can gain rights to occupied land through either a granted right of occupancy obtained from Village Councils that is subject to a designated lease period of a maximum of 99 yearsFootnote 635 or a customary right of occupancy that may be held indefinitely.Footnote 636 Finally, general land is public land that does not constitute reserved land or village land.Footnote 637 Tanzania’s land tenure system thus provides a clear legal basis for rural communities to exercise statutorily and customarily defined rights to manage, occupy, and use land within the boundaries of villages. On the other hand, the exercise of customary land rights claimed by communities on reserved or general lands has received less recognition and protection from central authorities and has moreover given rise to continued land disputes and conflicts between communities.Footnote 638

The Forest Act enables communities living in or adjacent to forests to control and manage or co-manage their forests through one of two mechanisms: Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM) and Joint Forest Management (JFM). The provisions on CBFM most notably allow villages to establish and manage, whether separately or jointly, a Village Land Forest Reserve (VLFR).Footnote 639 In order to do so, a village must establish that it holds tenure over a given forest, prepare a plan for its sustainable management, and adopt by-laws that support this plan (through the provision of fines or sanctions, for instance). The plan and the by-laws must then be ratified by the District Council, who can then declare the existence of a new VLFR. After three years, villages may moreover apply for their VLFR to be gazetted by the central government.Footnote 640 The creation of a VLFR provides local communities with clear and unambiguous statutory rights to manage and control forests and fully benefit from their resources, in line with their approved VLFR management plan.Footnote 641 As is recognized by the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources & Tourism, CBFM thus “aims to secure forests through sharing the rights to control and manage them, not just the right to use or benefit from them” and “targets communities not as passive beneficiaries but as forest managers.”Footnote 642 In contrast, JFM entails the adoption of joint forest management agreements between communities and the central government and does not therefore provide communities with additional statutory rights to govern forests or to access their benefits.Footnote 643

As of 2009, 1,460 villages (14 percent of all villages on mainland Tanzania) had engaged in CBFM and 395 forests had been declared or gazetted as VLFRs, thus placing 12 percent of unreserved forests under the direct control and authority of local communities.Footnote 644 However, local communities have also faced a number of challenges in the establishment and management of VLFRs, including their limited capacity to protect VLFRs from exploitation by outsiders participating in the growing trade in illegal timber. This has been compounded by the reluctance of some District Council officials to declare a new VLFR due to the potential loss of revenue (in the form of taxes and levies on the exploitation of forests or bribes or kickbacks received as part of their participation in illegal logging) that may result therefrom. These practical challenges have thus prevented many local communities from taking full advantage of Tanzania’s advanced CBFM regime.Footnote 645

The experience of local communities pales in comparison with the setbacks faced by Indigenous Peoples seeking recognition and protection of their customary lands and forests. Four ethnic communities identify as Indigenous Peoples in contemporary Tanzania: forest-dwelling hunter-gatherers known as the Hadzabe and the Akie and pastoralists known as the Maasai and the Barabaig.Footnote 646 Throughout the twentieth century, these communities experienced ill-treatment, discrimination, and deprivation at the hands of the German and British colonial authorities as well as the post-colonial government of Nyerere. They were evicted, frequently through force, from their traditional lands and forests to make way for the creation of forest and nature reserves and thereafter subjected to coercive regimes of wildlife and resource management that adversely affected their traditional livelihoods and cultural practices. Their lands, forests, and grazing tracts were also alienated to commercial and private interests, without their consent or receipt of any compensation. And their traditional systems of customary law and governance were disrupted through the imposition of external legal and administrative structures (such as the bifurcated property rights regime of the British or the villagization program of the Nyerere regime).Footnote 647

During the 1980s, members of the Maasai and Barabaig communities filed a number of lawsuits against the Tanzanian government and corporations that had dispossessed them of their lands. However, their attempts to gain recognition and restoration of their customary land rights before the Tanzanian courts were ultimately unsuccessful.Footnote 648 In the early 1990s, these communities began to establish links with, and draw inspiration from, the global Indigenous movement originating in Canada, Australia, and Latin America. They began to identify as Indigenous and formed a series of NGOs to advocate for the recognition of their status and rights as Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 649 In 1994, these NGOs most notably established a new umbrella organization known as Pastoralist and Indigenous NGOs (PINGOs) to serve as a “loose coalition of like minded pastoralist and hunter/gatherer community based organisations.”Footnote 650 With support from international donors, these NGOs sought to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the gradual liberalization of Tanzanian politics to press for the protection of their rights as Indigenous Peoples, especially in terms of their traditional rights to land.Footnote 651 Nevertheless, the effectiveness of Tanzania’s fledgling Indigenous movement has been limited due to its disjointed and disorganized nature as well as its detachment from the communities that it is meant to serve, and it has made few legal or political gains over the last two decades.Footnote 652

For one, the Hadzabe, Akie, Maasai, and Barabaig have not succeeded in being recognized as “Indigenous” by the Tanzanian government. Although Tanzania voted in favor of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, it has not acknowledged the existence of Indigenous Peoples on its territory nor has it adopted any national laws or policies that aim to recognize or protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 653 While recognizing that some ethnic groups may need “special protection,” the Government of Tanzania has maintained that all Tanzanians are “Indigenous.”Footnote 654 This position goes against an explicit recommendation adopted by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) calling on Tanzania to “[f]ormulate a definition of indigenous peoples that accommodates Tanzania’s circumstances and is consistent with the provisions and principles of the African Charter.”Footnote 655 The nonrecognition of Indigenous Peoples has been widespread across other segments of Tanzanian society that have viewed their traditional lifestyles as incompatible with the “modern” values of contemporary Tanzania.Footnote 656 Indigenous Peoples have thus experienced systematic discrimination as well as political and socioeconomic marginalization not only due to the policies of the Tanzanian government, but also due to the actions of the private sector, conservation actors, and rural communities.Footnote 657

In addition, Indigenous Peoples have, by and large, not benefited from land and forest reforms adopted in Tanzania in the late 1990s and early 2000s.Footnote 658 While some Indigenous communities in Tanzania have sought to establish customary rights of occupancy on their traditional lands under the Land Act and the Village Land Act, this option has remained riddled with a number of legal and bureaucratic obstacles, particularly their exclusion from the village-based unit of political administration and governance.Footnote 659 As such, most of the customary lands of Indigenous Peoples have been declared as reserve lands (particularly conservation or wildlife areas) or village lands (established during the ujaama vijijini era).Footnote 660 Indigenous Peoples have continued to face significant barriers in claiming and exercising their land and tenure rights, as well as eviction from their lands, pastures, and grazing areas.Footnote 661 The tenure insecurity that Indigenous Peoples face in Tanzania is all the more harmful since access to land and its resources is integral to their livelihoods and cultural practices.

4.2 The Pursuit and Governance of Jurisdictional REDD+ in Tanzania

The commencement of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Tanzania originates in the conclusion of a bilateral agreement in April 2008 with the government of Norway that established a “Climate Change Partnership with a focus on REDD.”Footnote 662 The original impetus for this agreement came largely from the Norwegian Embassy in Dar es Salaam and built on Norway’s long-standing support for forest conservation and governance in Tanzania.Footnote 663 In this early period in the emergence of REDD+ within the UNFCCC and around the world, Norwegian officials believed that supporting the operationalization of REDD+ in Tanzania could be used to demonstrate its potential role in contributing to the alleviation of poverty as well as its applicability in the dry woodlands that are common in much of sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 664 In turn, Norway’s interest in funding the implementation of REDD+ in Tanzania garnered significant interest both from the Tanzanian Vice President’s Office, which handles environmental issues and climate change, as well as the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, which oversees the management and governance of forests.Footnote 665 Tanzanian officials saw the pursuit of REDD+ readiness activities as an opportunity to take advantage of new funds to improve Tanzania’s forest management practices, contribute to poverty alleviation, and make a voluntary contribution to global climate mitigation efforts.Footnote 666

Pursuant to its bilateral partnership with Norway, Tanzania created a National REDD+ Taskforce bringing together six senior government officials from the Office of the Vice-President (Division of the Environment) and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (Forestry and Beekeeping Division) to coordinate its jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts in late 2008.Footnote 667 In addition, Tanzania also established a REDD+ Secretariat, hosted at the Institute of Resource Assessment (IRA) of the University of Dar es Salaam,Footnote 668 which was given the important task of receiving and administering the funding provided by Norway for the creation of a national REDD+ strategy. The establishment of this secretariat in a third-party institution outside of government was motivated by Norway’s lack of confidence in the ability of the MRNT to manage donor funds, in light of a corruption inquiry that was unresolved at the time. In addition, Norwegian and Tanzanian officials also shared an interest in finding a neutral platform that could facilitate the development of a national REDD+ strategy in a context where the MRNT and VPO were unable to agree as to who should hold primary responsibility for coordinating REDD+ readiness efforts.Footnote 669

From 2009 to 2014, Norway disbursed 58 million US dollars for the implementation of three types of REDD+ readiness activities in Tanzania. First, Norway provided more than 7 million US dollars to fund the preparation of a national REDD+ strategy. Second, Norway provided close to 30 million US dollars to support the development and operationalization of nine REDD+ pilot projects across Tanzania.Footnote 670 Third, it spent over 21 million US dollars to fund two major research, training, and infrastructure programs in collaboration with the Sokoine University of Agriculture, one focusing on climate change impacts, adaptation, and mitigation (CCIAM) and another supporting the development of a national system for the measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of forest carbon stocks.Footnote 671 Norway’s support for these various activities created momentum, generated knowledge, and increased capacity for the pursuit of REDD+ in Tanzania.Footnote 672 Yet, despite the important role that Norway played in the inception and funding of REDD+ in Tanzania,Footnote 673 Tanzanian officials pursued their REDD+ readiness activities in a relatively autonomous fashion.Footnote 674 Indeed, Norwegian officials aimed to foster Tanzanian ownership of REDD+ and thus sought to influence REDD+ readiness efforts through dialogue rather than through the use of conditionality or overt political pressure.Footnote 675

In addition to the bilateral support provided by Norway, Tanzania received close to four million US dollars in assistance from a dedicated UN-REDD National Programme for its jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts.Footnote 676 From 2009 to 2013, this program provided funding, capacity-building, and technical assistance in order to support the design of a national governance framework for REDD+, the development of a national MRV system, the effective implementation of REDD+ at district and local levels, and the generation of a broad consensus among multiple stakeholders for the pursuit of REDD+ in Tanzania.Footnote 677 Apart from its important role in providing technical support for developing Tanzania’s MRV capabilities, the influence of the UN-REDD Programme on Tanzania’s REDD+ readiness efforts was limited, however. For one, Tanzania had already initiated the development of its national REDD+ strategy with support from Norway by the time the National UN-REDD Programme was operational and officials from the UN-REDD Programme struggled to ensure that their work was relevant to Tanzania’s ongoing efforts on REDD+ readiness.Footnote 678 For another, the availability of funding from Norway and the few strings attached made it possible for Tanzanian officials to dismiss the advice and knowledge products provided by the UN-REDD Programme.Footnote 679

Finally, Tanzania submitted an R-PP to the World Bank FCPF in 2010 that was subsequently approved by the World Bank FCPF in 2011.Footnote 680 Although it went through the exercise of preparing and submitting an R-PP to the FCPF, Tanzania did not seek funding from the FCPF Readiness Mechanism as such and used its membership within the FCPF Participant’s Committee as an opportunity to stay engaged in international discussions of REDD+ as well as to learn from the experience of other developing countries pursuing REDD+ readiness efforts.Footnote 681 Tanzania did not receive direct technical support and assistance from the FCPF as such, and the FCPF exerted little influence on the design and implementation of Tanzania’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts.Footnote 682

4.3 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Jurisdictional REDD+ Readiness Activities in Tanzania

4.3.1 Rights in the National REDD+ Strategy

The National REDD+ Taskforce initiated Tanzania’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities in January 2009 with a four-day multi-stakeholder planning workshop and a series of field trips to Australia, Norway, and Brazil in May and June 2009.Footnote 683 In August 2009, it launched a National REDD Framework that identified the key elements of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness that Tanzania would aim to achieve and offered a multi-year roadmap for the development of a national REDD+ strategy.Footnote 684 This framework recognized the potential adverse implications of REDD+ for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities as well as the benefits their engagement might bring in the creation and implementation of a national REDD+ strategy.Footnote 685 In particular, Tanzania’s National REDD Framework identified enhanced support for participatory forest management as a potential pathway for reducing carbon emissions in TanzaniaFootnote 686 as well as recognizing the critical importance of secure land tenure and community rights for the sustainable management of forests.Footnote 687

From August to October 2009, the National REDD+ Taskforce undertook an initial series of consultations on the development of a national REDD+ strategy.Footnote 688 This initial set of consultations enabled the National REDD+ Taskforce to gauge the challenges involved in discussing REDD+ at the local level, especially since the specific ways in which the eventual implementation of REDD+ in Tanzania might affect the interests of local communities were not necessarily apparent or easy to communicate.Footnote 689 In the synthesis document resulting from the consultations, the National REDD+ Taskforce committed to ensuring “the active participation/involvement of local communities in developing, implementing and monitoring REDD activities,” including through additional local consultations and awareness-raising.Footnote 690 The consultations also generated a number of preliminary conclusions that would be reflected in the National REDD+ Taskforce’s bifurcated approach to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. On the one hand, the synthesis acknowledged the critical importance of forests for the livelihoods, sustenance, and cultural practices of rural communities, highlighted the central role the establishment of VLFRs could play in reducing carbon emissions in Tanzania, and singled out forest-dependent communities as an important group whose interests should be considered in a national REDD+ strategy and who should therefore be consulted as part of its development.Footnote 691 On the other hand, the synthesis failed to recognize the status of Indigenous Peoples in Tanzania, concluding that “few communities can rightly be called ‘indigenous’ people like the Red Indians of the USA, the Aborigines of Australia or the Bambuti pigmies of Congo forests,” and that “[t]he only people who could be described as ‘indigenous’ would be the Hadzabe people of Lake Eyasi who are heavily dependent on forest resources for their livelihoods.”Footnote 692

Alongside the consultations that it undertook and the studies that it commissioned to develop a national REDD+ strategy for Tanzania, the National REDD+ Taskforce also prepared an R-PP for submission to the FCPF – a process that brought issues specifically relating to Indigenous Peoples and their rights to the foreground. The draft version of the Tanzanian R-PP submitted to the FCPF in the spring of 2010 highlighted the valuable contributions of participatory forest management in Tanzania and stressed the need to engage local communities in the implementation of REDD+ activities.Footnote 693 This R-PP included no references to the rights or engagement of Indigenous Peoples, however.Footnote 694 This triggered criticisms and suggestions from the FCPF Technical Advisory PanelFootnote 695 as well as the FCPF Participants’ Committee.Footnote 696 In response, the National REDD+ Taskforce submitted a revised R-PP in October 2010 that recognized the existence of “concerns” regarding “the rights of indigenous people and communities dependent on forests and the impact of REDD programmes on such groups.”Footnote 697 In an annex, the revised R-PP nonetheless specified that: “Tanzania, in principle, does not have Indigenous People but has communities living in and close to forests who’s (sic) livelihoods depend greatly on the forests. These are recognized as forest dependent and forest adjacent people.”Footnote 698 This revised version of Tanzania’s R-PP attracted another series of criticisms and recommendations from a different set of experts from the FCPF Technical Advisory Panel as well as reviewers within the FCPF Secretariat, who all stressed the need for additional consultations with stakeholders and a greater focus on land and tenure rights in the development of Tanzania’s R-PP.Footnote 699 Regarding the recognition of the concept of Indigenous Peoples, the FCPF Secretariat explained that this would henceforth be discussed “at the broader portfolio level between the Government of Tanzania and the World Bank” and was, in effect, no longer identified as a critical issue in the development of Tanzania’s R-PP.Footnote 700

A coalition of conservation and development NGOs implementing REDD+ pilot projects in Tanzania submitted similar recommendations for the finalization of Tanzania’s R-PP to the FCPF and the National REDD+ Taskforce. These recommendations did not refer to Indigenous Peoples, but focused instead on the enhancement of community rights through Tanzania’s REDD activities, the definition and scope of village rights to govern forests on general lands, and the need for greater civil society participation in Tanzania’s REDD+ readiness activities, most notably through representation on the National REDD+ Taskforce.Footnote 701 Pursuant to these various suggestions, the FCPF Participants’ Committee requested, in November 2010, that Tanzania implement additional changes to its R-PP that included “giving due consideration to the representation of and engagement with civil society, forest dependent people, and associations of Wildlife Management Areas in the national and subnational policy and decision making bodies on REDD+, including the national Task Force” and “further clarify[ing] and elaborat[ing] on land tenure and related rights, and how these will be incorporated into benefit-sharing systems.”Footnote 702 As such, despite the fact that the World Bank’s Operational Policy on Indigenous Peoples would be applicable to the delivery of any funding Tanzania might receive from the FCPF for its REDD+ readiness activities, Tanzania’s refusal to acknowledge the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples did not stand in the way of the approval of its R-PP by the FCPF Participants’ Committee at a later meeting.Footnote 703

In December 2010, the National REDD+ Taskforce released a first draft of Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy,Footnote 704 which reproduced much of the language that had been adopted in the synthesis document on the consultations held in the fall of 2009 and the R-PP Tanzania submitted to the FCPF in October 2010.Footnote 705 As such, the draft strategy focused on lessons learned from Tanzania’s experience with community-based forest management and the way in which the country could contribute to, and benefit from, from the pursuit of REDD+ activities.Footnote 706 It envisaged several strategic interventions for REDD+ that would reduce poverty and support livelihoods among rural communities,Footnote 707 strengthen forest governance,Footnote 708 and enhance participatory land-use planning and conflict resolution.Footnote 709 As far as Indigenous Peoples were concerned, the draft strategy cited the safeguards recently adopted within the UNFCCC in Cancun, including those relating to the knowledge and rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and their full and effective participation in REDD+ activities.Footnote 710 It also highlighted that Tanzania had signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,Footnote 711 and included the World Bank’s definition of Indigenous Peoples in its glossary.Footnote 712 On the other hand, the draft strategy averred that “the issue of engagement of ‘indigenous peoples’ in Tanzania is being handled via the concept ‘forest-based communities’ rather than ‘indigenous peoples’ – a concept which some stakeholders found derogatory and discriminatory.”Footnote 713 In this regard, the draft strategy further identified “the Hadzabe people of Lake Eyasi who are heavily dependent on forest resources for their livelihoods” and “groups like pastoralists and other communities living adjacent to forest reserves” as forest-based communities and stressed the importance of considering their interests and building on their knowledge and practices in the design and implementation of REDD+ in Tanzania.Footnote 714

During the first quarter of 2011, the National REDD+ Taskforce organized a series of multi-stakeholder workshops to discuss the draft National REDD+ Strategy in seven zones across TanzaniaFootnote 715 and solicited feedback from key international and domestic interlocutors. Through written comments and ongoing dialogue, the Norwegian Embassy pressed the National REDD+ Taskforce to recognize the distinctive status and rights of Indigenous Peoples as separate from forest-dependent communities.Footnote 716 For its part, the UN-REDD Programme did not raise the issue of Indigenous rights and instead highlighted the importance of holding additional stakeholder consultations as well as broadening the membership of the National REDD+ Taskforce to include civil society representatives.Footnote 717 Finally, the conservation and development NGOs implementing REDD+ pilot projects in Tanzania released a series of briefs and statements that reiterated many of their previous recommendations regarding strengthening participatory forest management, including civil society in decision-making, recognizing community rights to unreserved forests, and creating opportunities for communities to receive direct payments from REDD+ activities. They also included a new recommendation (stemming from the recent adoption of the Cancun Agreements) that the national strategy contain a set of social and environmental safeguards.Footnote 718

In early 2012, the National REDD+ Taskforce responded to some of these comments by naming a civil society representative to the taskforceFootnote 719 and creating a technical working group to focus on legal, governance, and safeguards issues.Footnote 720 In what has been described as a “milestone achievement” for the recognition of the status of Indigenous Peoples in the Tanzanian policy-making process,Footnote 721 this working group included a representative from “Pastoralists and Hunter Gatherer Organizations.”Footnote 722 Although these two nominations provided new opportunities for civil society advocates to influence the development of the national REDD+ strategy, the work of the National REDD+ Taskforce continued to be largely dominated by government representatives and their views on the future of REDD+ in Tanzania.Footnote 723 This is clearly reflected in the text of the draft National REDD+ Strategy released in June 2012.Footnote 724 While it acknowledged the role that the allocation of land and tenure rights for local communities and the establishment of VLFRs could play in the pursuit of REDD+ in Tanzania,Footnote 725 this second draft strategy did not recognize the customary rights of villages to manage their forests on unreserved landsFootnote 726 and continued to privilege a national funding mechanism for receiving international payments for REDD+ and channeling related benefits to local communities.Footnote 727 With respect to Indigenous Peoples, the strategy omitted all references previously included in the first draft to Indigenous Peoples, pastoralists, hunter-gatherers, or the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 728 That said, this second draft strategy included new commitments to adopting a set of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+Footnote 729 and undertaking a strategic and social impact assessment that would “give special consideration to livelihoods [and] resource use rights (including those of forest dependent Peoples).”Footnote 730 The release of the second draft strategy prompted a number of international and domestic stakeholders to reiterate their concerns and recommendations regarding the need to further recognize and engage with Indigenous Peoples,Footnote 731 explicitly recognize and clarify the land and tenure rights of villages in relation to unreserved forests and the carbon stored in village forests,Footnote 732 consider adopting a nested approach for the management of international REDD+ payments and the sharing of benefits derived therefrom,Footnote 733 and systematically integrate social and environmental safeguards into the very body of the strategy.Footnote 734

During the summer and fall of 2012, the National REDD+ Taskforce undertook a final series of consultations across Tanzania, held a series of dialogues with stakeholders involved with REDD+ pilot projects, and organized workshops with parliamentarians in the Zanzibar House of Representatives and the Parliament of Tanzania.Footnote 735 After one final rewrite by the National REDD+ Taskforce, the National REDD+ Strategy was formally approved by the National Climate Change Steering Committee and launched in March 2013.Footnote 736 Like previous drafts, the final draft of Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy adopts an approach that supports the engagement and rights of local communities in the development and implementation of REDD+ activities while simultaneously excluding Indigenous Peoples and their rights from its purview. As far as participatory rights are concerned, Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy includes as one of its main objectives and result areas the engagement and active participation of multiple stakeholders in the design and implementation of REDD+ schemes.Footnote 737 To this end, the National REDD+ Strategy envisages numerous strategic actions, including building the capacity of local communities in relation to REDD+Footnote 738, engaging domestic civil society organizations, and learning from their experiences with pilot projects.Footnote 739 On the other hand, Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy does not recognize the importance of the right to FPIC, nor does it acknowledge the role that traditional knowledge might play in the design and implementation of REDD+ activities.Footnote 740

Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy is much more comprehensive in its approach to the substantive rights of local and forest-dependent communities and recognizes that an effective REDD+ mechanism will build on as well as contribute to the promotion of rights and livelihoods.Footnote 741 The National REDD+ Strategy most notably identifies the following as key strategic actions for reducing carbon emissions from forest-based sources: improving access to energy alternatives and economic opportunities for forest-dependent communities,Footnote 742 scaling up community-based forest management,Footnote 743 accelerating participatory land-use planning (leading to land reforms and the issuance of customary rights of occupancy),Footnote 744 and supporting the demarcation and mapping of village lands.Footnote 745 At the same time, despite its emphasis on participatory forest management and poverty alleviation, the National REDD+ Strategy maintains a preference for the creation of a national fund to receive and manage REDD+ finance.Footnote 746 This went against the demands of conservation and development NGOs, who had advocated for a nested mechanismFootnote 747 and were generally concerned about the ability of a central government-run mechanism to deliver benefits to local communities.Footnote 748 As such, the establishment of an equitable and transparent mechanism for REDD+ finance and benefit-sharing remains one of the key outstanding issues that Tanzania must resolve in order to be ready for the full operationalization of REDD+ at the national level.Footnote 749

Another key element of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness that was not finalized in Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy relates to the adoption of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+.Footnote 750 Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy includes a commitment to develop and enforce social and environmental safeguards to ensure that REDD+ activities deliver multiple benefits, including in terms of “forest dependent communities’ rights,” and to limit its potential adverse impacts on “the livelihoods and rights of communities.”Footnote 751 To this end, the strategy plans for the establishment of a national safeguards information system in accordance with the requirement set by the Cancun Agreements, as well as the operationalization of safeguards based on Tanzania’s existing laws and policies and drawing on the standards adopted by the UNFCCC, the UN-REDD Programme, the World Bank, and the REDD+ SES.Footnote 752 In this second regard, Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy emphasizes that an eventual set of social and environmental safeguards “will give special consideration to livelihoods, resource use rights (including those of forest dependent Peoples), conservation of biodiversity, cultural heritage, gender needs, capacity building and good governance.”Footnote 753

In comparison with the first draft of the National REDD+ Strategy released in December 2010, the final draft includes fewer references to and less consideration of the rights and status of Indigenous Peoples in Tanzania. Unlike previous drafts and other policy documents, the final draft does not even explain whether the concept of Indigenous Peoples is applicable in Tanzania, nor does it identify forest-dependent communities or discuss their distinctive character and needs. What is more, Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy proposes a number of interventions that could have negative impacts on Indigenous Peoples in Tanzania, most notably in its identification of pastoralism as a driver of deforestation and forest degradation and its commitment to reviewing “livestock policy and strategies to reduce overgrazing and nomadic pastoral practices” and supporting “commercial livestock destocking campaigns.”Footnote 754 Given the economic and political marginalization of pastoralists in Tanzania and the barriers that stand in the way of recognition of their customary land rights, the implementation of these types of REDD+ activities could cause significant harm to Indigenous pastoralist communities like the Maasai and the Barabaig.Footnote 755

All told, the National REDD+ Strategy presents meaningful opportunities for jurisdictional REDD+ activities to support the implementation of the rights of forest-dependent communities to govern their forests in line with the existing mechanisms laid out in the Forest Act. That said, the extent to which arrangements for REDD+ finance and benefit-sharing may enable communities to actually benefit from the funds generated by REDD+ remains an open question. Whatever challenges local communities may face in accessing the benefits engendered by REDD+, they still fare much better than Indigenous Peoples. Indeed, the National REDD+ Strategy completely ignores the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples and even creates important risks for the continuation of the traditional livestock practices of pastoralists.

4.3.2 Rights in the Social and Environmental Safeguards for REDD+

The development of safeguards for REDD+ in Tanzania was first identified as an item to be addressed in the National REDD Framework adopted by the National REDD+ Taskforce in August 2009.Footnote 756 The National REDD+ Taskforce subsequently invited a team from the REDD+ SES Initiative to hold a series of meetings and workshops with multiple stakeholders in September 2009 to discuss the development of social and environmental safeguards in Tanzania.Footnote 757 This visit provided an opportunity for Tanzanian officials and nongovernmental representatives to learn about the concept and importance of safeguardsFootnote 758 and revealed differences of opinion between the team from the REDD+ SES Initiative and the Tanzanian participants regarding the definition and application of concepts such as Indigenous Peoples, forest-dependent communities, and customary rights in Tanzania.Footnote 759

Despite this initial swell of interest and the fact that two Tanzanians, one from government and the other from civil society, joined the international steering committee of the REDD+ SES Initiative,Footnote 760 the development of social and environmental safeguards remained dormant in Tanzania for two years due to the National REDD+ Taskforce’s reluctance to apply external standards in sensitive areas of law and policy.Footnote 761 However, the emergence of safeguards information systems as an element of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness within the UNFCCC in 2010 and the combined pressures from international and domestic interlocutors for Tanzania to adopt its own set of social and environmental safeguards eventually led the National REDD+ Taskforce to create a technical working group on legal, governance, and safeguards issues and recruit a consultant to facilitate the process of applying and interpreting the REDD+ SES in early 2012.Footnote 762 Throughout 2012 and the first half of 2013, the National REDD+ Taskforce and the National REDD+ Secretariat completed the first steps set out in the guidelines for the use of the REDD+ SES, including the organization of awareness raising and capacity-building activities, the selection of a facilitation team, and the creation of a multi-stakeholder standards committee.Footnote 763 A first draft of the social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ was prepared by the consultant and finalized through a series of workshops held with government officials and representatives of the pilot projects.Footnote 764 This draft was released in June 2013Footnote 765 and was discussed through a series of consultations held with multiple stakeholders across Tanzania during the summer of 2013.Footnote 766 A final draft policy on social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ was then approved by the National Climate Change Steering Committee and adopted by the Vice President’s Office in October 2013.Footnote 767

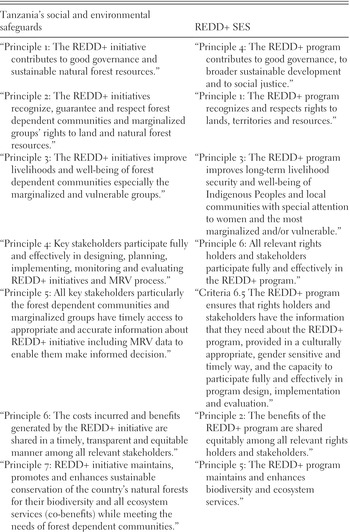

Tanzania’s REDD+ social and environmental safeguards policy explains that these safeguards are meant to provide a “country-specific tool” to operationalize the REDD+ safeguards listed in the Cancun AgreementsFootnote 768 and ensure “that implementation of REDD+ activities respect the rights of all relevant stakeholders including forest dependent communities, avoid social and environmental harm and generate significant benefits for the present and future generations.”Footnote 769 The safeguards are comprised of eight principles, forty-eight criteria, and 107 indicators, and the safeguards policy provides a thorough overview of how each of these principles relate to existing laws and institutions in Tanzania as well as the safeguards included in the Cancun Agreements. Although the safeguards policy claims they were drafted on the basis of a wide range of international and foreign sources, Table 4.1 demonstrates that the structure and content of the safeguards were primarily developed through an adaptation of the REDD+ SES to the context of Tanzanian law and policy.

Through their sustained and detailed emphasis on good forest governance, land and resource rights, support for livelihoods, full and effective participation, equitable sharing of benefits, and dispute resolution mechanisms, Tanzania’s social and environmental safeguards are strongly supportive of the participatory and substantive rights of forest-dependent communities. On the other hand, Tanzania’s social and environmental safeguards fail to recognize or protect the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples. Although the safeguards policy includes a few brief allusions to Indigenous Peoples in its discussion of international guidance on REDD+ safeguards,Footnote 770 the actual principles, criteria, and indicators that form the heart of the safeguards themselves do not include any references to Indigenous Peoples or their rights. The only clear consideration of the concept of Indigenous Peoples is in the policy’s glossary, where it is subsumed within a broader definition of forest-dependent communities.Footnote 771 In fact, all of the references to Indigenous Peoples and local communities included in the REDD+ SES have been replaced by the term “forest-dependent communities and marginalized groups” in Tanzania’s social and environmental safeguards. For instance, whereas criterion 1.3 of the REDD+ SES provides that “[t]he REDD+ program requires the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples and local communities for any activities affecting their rights to lands, territories and resources,” criterion 2.2 of Tanzania’s social and environmental safeguards mandates that “[t]he REDD+ initiative promotes and respects the right to free prior and informed consent (FPIC) of forest dependent communities and marginalized groups for any REDD+ activities that might affect their rights to land and natural resources.” This application of the right to free, prior, and informed consent to forest-dependent communities is striking for two reasons. For one, it represents a complete transformation of this right, which first emerged in relation to Indigenous Peoples under international human rights law,Footnote 772 was then extended to local communities within the REDD+ SES,Footnote 773 and now applies to forest-dependent communities only in the Tanzanian context. For another, it recognizes and aims to protect a right that forest-dependent communities do not hold, under Tanzanian law, outside of the structure of the village unit of governance under the Village Land Act and Forest Act.Footnote 774 Accordingly, the development and adoption of Tanzania’s social and environmental safeguards led to the expansion of the rights held by local communities, while simultaneously neglecting those of Indigenous Peoples.

4.4 Explaining the Conveyance and Construction of Rights through Jurisdictional REDD+ Activities in Tanzania

The development of a National REDD+ Strategy and a safeguards policy in Tanzania reflect two very different outcomes with respect to the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. In essence, the National REDD+ Strategy reflects the nonconveyance of exogenous legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Indeed, in spite of the efforts of multiple international actors (Norway, the FCPF, and the UN-REDD Programme) and the advocacy of Indigenous activists, the National REDD+ Taskforce never adopted the exogenous legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the context of its National REDD+ Strategy. I would argue that this can be best explained by the enduring resilience of a powerful counter-norm to the effect that all Tanzanians are Indigenous and that the concept of Indigenous Peoples is a concept that applies to pre-colonial communities in the Americas, but not Africa.Footnote 775 This counter-norm appears to have prevented the internalization of any exogenous norms relating to the concept and rights of Indigenous Peoples in the context of the National REDD+ Strategy.Footnote 776 In addition, this outcome may also stem from the inability of Indigenous Peoples in Tanzania to effectively mobilize for the recognition of their status and rights. In this regard, it bears mentioning that the Indigenous movement in Tanzania is disjointed and fragmented and has not managed to build effective alliances with other domestic or international actors both in general and in the specific context of Tanzania’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness process.

While Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy does recognize the importance and role of the forest, land tenure, and resource rights of local communities in the design and development of REDD+ activities, I would argue that this can be primarily explained by the existing endogenous legal norms in Tanzania. Throughout the development of the National REDD+ Strategy, the National REDD+ Taskforce identified the implementation of the CBFM and JFM provisions under the Forest Act as central to the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Tanzania.Footnote 777 This commitment to community-based approaches to forest governance stemmed first and foremost from a belief on the part of the National REDD+ Taskforce that community forestry constituted an effective and efficient way of addressing important local drivers of deforestation and generating reductions in carbon emissions in forests. For the most part, this belief was itself embedded in pre-existing shared understandings about the legitimacy of village governance and the superiority of wparticipatory forest management that had developed in Tanzania throughout the 1990s and were formally enshrined in the Village Land Act and Forest Act. Accordingly, the creation of a strategy for jurisdictional REDD+ can itself be seen as an exogenous legal norm that was translated by the National REDD+ Taskforce on the basis of the endogenous legal norms that defined the appropriateness of community-based mechanisms in Tanzanian forest governance.Footnote 778

On the other hand, the National REDD+ Taskforce never altered its position about the necessity of creating a national trust fund to receive, manage, and channel payments for REDD+,Footnote 779 despite the preference for a nested REDD+ finance mechanism that was clearly, constantly, and unanimously expressed by the proponents of all nine REDD+ pilot projectsFootnote 780 as well as the civil society representatives serving on the National REDD+ Taskforce and its technical working groups.Footnote 781 In all likelihood, the National REDD+ Taskforce’s steadfast refusal to consider a nested approach to REDD+ finance was motivated by a strong inclination to retain control and influence over the management and distribution of funding for REDD+.Footnote 782 Indeed, while the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities may have been seen as an opportunity for Tanzanian government officials to implement existing mechanisms relating to participatory forest management, it was also perceived as an opportunity to increase funding for the Forest and Beekeeping Department.Footnote 783 The material interests of Tanzanian government officials thus explain the incongruous manner in which the National REDD+ Strategy recognizes local communities as best placed to manage forests under REDD+, while at the same time denying them the capacity to access or manage the funds that might be generated by REDD+ activities.Footnote 784 All told, the elaboration of a National REDD+ Strategy reflects the influence of endogenous, rather than exogenous, legal norms, especially as far as the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are concerned.

Unlike the National REDD+ Strategy, Tanzania’s policy on social and environmental safeguards reflects the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. I would argue that this process can be explained by a causal sequence involving multiple causal mechanisms. To begin with, the National REDD+ Taskforce’s commitment to developing a policy on social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ was driven by the combined effect of the mechanisms of cost-benefit adoption and mobilization. Once the development of an information system for reporting on social and environmental safeguards became a core requirement for jurisdictional REDD+ readiness and was tied to the delivery of finance for REDD+, Tanzanian officials recognized that it would be necessary for Tanzania to develop a policy on social and environmental safeguards in order to eventually access sources of finance for REDD+ and remain in compliance with its obligations under the UNFCCC.Footnote 785 At the domestic level, the proponents of the REDD+ pilot projects also repeatedly pressed the National REDD+ Taskforce to adopt a set of social and environmental safeguards, with a particular emphasis on protections for the rights of local communities, as part of Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy.Footnote 786 In response, as was discussed in Section 4.4.2, the National REDD+ Taskforce developed a policy on social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ using the process and guidance set by the REDD+ SES Initiative. In other words, the National REDD+ Taskforce committed to an exogenous legal norm – the need to develop a set of social and environmental safeguards – because of the material benefits that it might gain in doing so (cost-benefit adoption) and due to the political pressure exerted by domestic civil society actors (mobilization).

Whereas the mechanisms of cost-benefit adoption and mobilization triggered the conveyance of legal norms relating to the development of social and environmental safeguards, the construction of the participatory rights of forest-dependent communities in these safeguards are best explained by the mechanism of persuasive argumentation. A process of argumentation facilitated by the novelty of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ efforts meant that Tanzanian government officials were open to new normative understandings about the importance of social safeguards for REDD+, including those relating to the participatory rights of forest-dependent communities.Footnote 787 Moreover, the flexible guidance set by the UNFCCC and the REDD+ SES Initiative for the development of a policy on social and environmental safeguards fostered the engagement of Tanzanian government officials in a deliberative discourse with other domestic actors and their international interlocutors around the nature and extent of participatory rights in the context of REDD+.Footnote 788 In this process, the national consultant who facilitated the application of the REDD+ SES Initiative served as a key intermediary in ensuring that exogenous legal norms relating to participatory rights were effectively adapted to the Tanzanian context and appropriated by Tanzanian government officials.Footnote 789 I thus argue that persuasive argumentation explains why and how exogenous legal norms that define the participatory rights of “Indigenous Peoples and local communities” in the Cancun Agreements and in the REDD+ SES were translated in line with existing endogenous norms in Tanzania and led to the construction of hybrid legal norms recognizing similar rights for “forest-dependent communities and marginalized communities,” but not for Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 790 In other words, the construction of hybrid legal norms relating to social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ in Tanzania also reflects the enduring influence of an endogenous norm that denies the status, existence, and rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 791 The resilience of this endogenous norm also explains why the material and social pressures to recognize the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples that were exerted by the Norwegian Embassy, the World Bank FCPF, and the UN-REDD Programme were ultimately unsuccessful in getting Tanzania to alter its position on this matter.

4.5 REDD+ and the Future of Indigenous and Community Rights in Tanzania

This chapter has shown that the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities has resulted in the enactment of an enhanced set of participatory and substantive rights for forest-dependent communities in Tanzania. Notwithstanding ongoing disagreements over the establishment of finance and benefit-sharing arrangements for REDD+, Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy and its safeguards policy recognize the importance of respecting and protecting the participatory and substantive rights of forest-dependent communities in the design and implementation of REDD+ activities, including their right to free, prior, and informed consent. The long-term implications of these developments are hard to discern because the future prospects of jurisdictional REDD+ in Tanzania remain uncertain as of August 2014. At the moment, the Tanzanian government is aiming to obtain additional funding from the Norwegian government to complete its jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts.Footnote 792 Without additional support from donors, the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness policies developed by Tanzania are unlikely to be implemented,Footnote 793 which would not only limit the impacts of these policies on the ground, but also undoubtedly constrain their influence on the adoption of policies in related sectors such as forestry, agriculture, and social development. What is more, as Tanzania’s economy becomes increasingly integrated into the global market for agricultural commodities, the Tanzanian government’s interest in the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ policies may further diminish.Footnote 794

Nonetheless, there are two reasons to think the recognition of the rights of forest-dependent communities in the context of jurisdictional REDD+ might have durable effects. The first reason has to do with the fact that these rights constitute hybrid legal norms that were constructed on the basis of endogenous Tanzanian norms regarding the role of these communities in forest governance as well as the nonexistence of Indigenous Peoples on Tanzanian soil. The legal norms relating to the rights of forest-dependent communities were effectively translated and appropriated by Tanzanian officials as well as domestic CSOs throughout the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness process. The enhanced normative resonance of these hybrid legal norms suggests they may influence Tanzania’s law, policies, and practices in forest governance and other policy sectors in the years to come.

The second reason has to do with the many ways in which domestic CSOs have been empowered as a result of the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness phase. It is important to highlight that the relatively consultative manner in which jurisdictional REDD+ policies were elaborated, as reflected in the inclusion of representatives from CSOs in the National REDD+ Taskforce and its technical working groups and the organization of an iterative series of multi-stakeholder consultations and workshops, stands in sharp contrast to the usual policy-making practices that prevail in Tanzania.Footnote 795 To the extent this precedent has redefined the expectations of government officials, domestic CSOs, and donors it may have durable implications for future policy-making processes in forestry and other sectors.Footnote 796 Most importantly, given the resources, credibility, and capabilities that domestic CSOs have acquired as a result of the direct support they have received from Norway and their work in developing and implementing REDD+ projects on the ground,Footnote 797 domestic CSOs are well-positioned to advocate for greater recognition of, and support for, the rights of forest-dependent communities in the context of the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ policies as well as forest governance and policy more broadly.Footnote 798

On the other hand, this chapter has also shown that the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities has done very little to foster recognition of and protection for the distinctive status and rights of Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia. Their inclusion in a technical working group of the National REDD+ Taskforce was lauded as a “milestone”Footnote 799 by international observers working on Indigenous rights and is viewed as an important development that created space for them to advocate for their rights.Footnote 800 But the reality is that the National REDD+ Strategy and safeguards policy fail to recognize their very existence as defined under international law and creates risks that the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ policies may only serve to further marginalize them. This is consistent with the Tanzanian government’s continuing rejection of the application of the concept of Indigenous Peoples in international foraFootnote 801 as well as pursuit of policies in which Indigenous Peoples continue to experience significant tenure insecurity.Footnote 802

All told, the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness phase can be said to have reinforced endogenous legal norms and practices that have progressively given local communities greater rights and authority over their lands and forests over the last decade, while denying similar protections to Indigenous Peoples. As such, for good and for bad, the recognition and protection of rights in the context of the jurisdictional REDD+ cannot be divorced from the broader achievements and failures that various international and domestic actors have had in pressing for increased respect for human rights and local autonomy since the end of authoritarian socialism in Tanzania.