Book contents

- Platonist Philosophy 80 bc to ad 250

- Cambridge Source Books in Post-Hellenistic Philosophy

- Platonist Philosophy 80 bc to ad 250

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Studying Middle Platonism

- Chapter 1 Plato’s Authority and the History of Philosophy

- Chapter 2 Making Sense of the Dialogues

- I Cosmology

- II Dialectic

- III Ethics

- Glossary

- References

- Catalogue of Platonists

- Index of Sources and References

- Index to the Notes and Further Reading

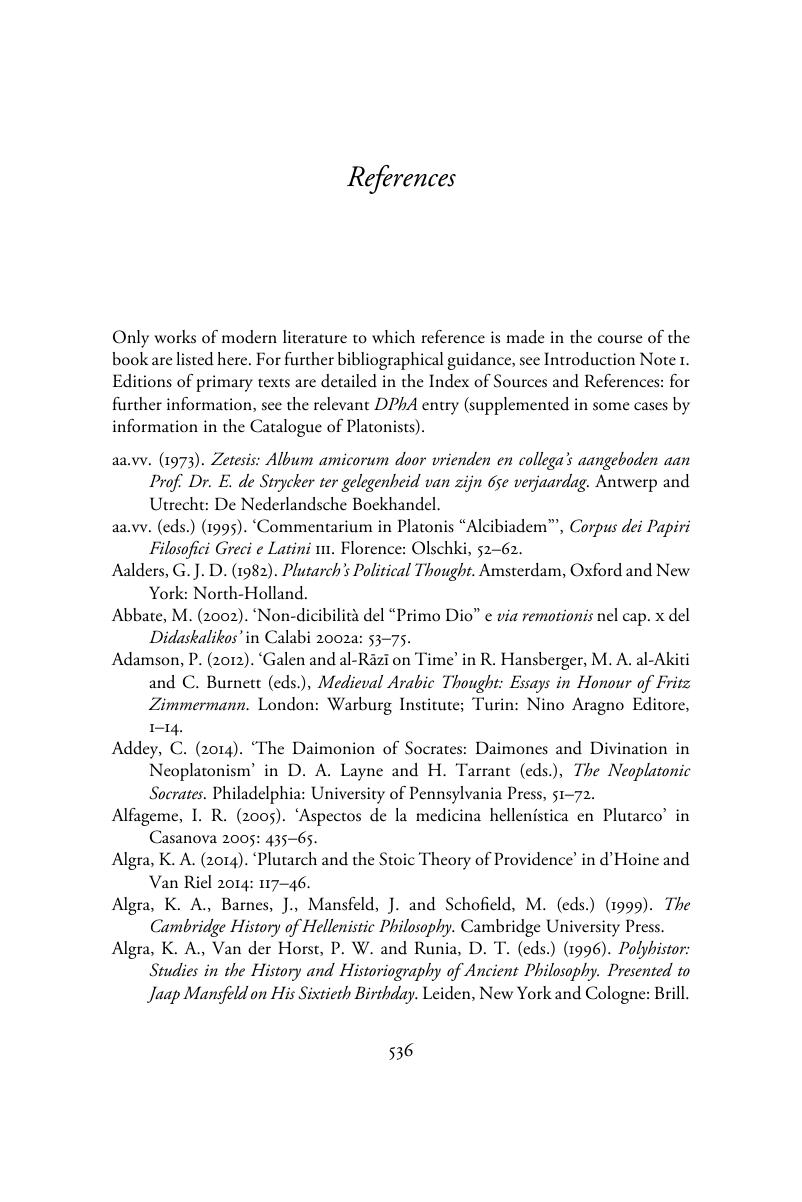

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 December 2017

- Platonist Philosophy 80 bc to ad 250

- Cambridge Source Books in Post-Hellenistic Philosophy

- Platonist Philosophy 80 bc to ad 250

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Studying Middle Platonism

- Chapter 1 Plato’s Authority and the History of Philosophy

- Chapter 2 Making Sense of the Dialogues

- I Cosmology

- II Dialectic

- III Ethics

- Glossary

- References

- Catalogue of Platonists

- Index of Sources and References

- Index to the Notes and Further Reading

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Platonist Philosophy 80 BC to AD 250An Introduction and Collection of Sources in Translation, pp. 536 - 592Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017