1.1 School Attendance and School Absenteeism

A century of work attests to the fact that school attendance and school absenteeism are key issues for scholars, practitioners and researchers from many fields [Reference Heyne, Gren-Landell, Melvin and Gentle-Genitty1]. School attendance is a primary mechanism to improve and predict student achievement [Reference Allensworth, Balfanz, Gottfried and Hutt2], prepare young people for successful transition to adulthood [Reference Fredricks, Parr, Amemiya, Wang and Brauer3] and enhance their economic and social participation in society [Reference Zaff, Donlan, Gunning, Anderson, McDermott and Sedaca4]. Conversely, school absenteeism is associated with impaired socio-emotional development [Reference Malcolm, Wilson, Davidson and Kirk5], even from a young age [Reference Gottfried6], and is predictive of school dropout [Reference Schoeneberger7], which predicts unemployment [Reference Attwood and Croll8] and lower life expectancy [Reference Rogers, Hummer and Everett9]. Furthermore, longitudinal data from different countries reveals sustained or increased rates of absenteeism [Reference Heyne, Gentle-Genitty, Gren Landell, Melvin, Chu and Gallé-Tessonneau10], exacerbating burdens on schools [Reference Balu and Ehrlich11] and society [Reference Evans12].

Recently, a greater sense of urgency surrounding school attendance and school absenteeism has emerged because of federal mandates in different countries regarding these constructs [Reference Gottfried, Hutt, Gottfried and Hutt13]. In the United States, for example, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) renders absenteeism a formal accountability metric for schools [Reference Hutt, Gottfried, Gottfried and Hutt14]. This is also true in the United Kingdom, where attendance and punctuality feature in the Ofsted school inspection framework [15]. Greater consistency in defining chronic absenteeism (i.e. 10% or more of enrolled days) has been established in these and other countries [16] (see also Chapter 2 for further discussion) such that greater emphasis is being placed on the risks posed by chronic absenteeism [Reference Hough, Gottfried and Hutt17]. This has resulted in a new wave of research [Reference Ehrlich, Johnson, Gottfried and Hutt18]. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce this research and to highlight three themes that emerge throughout the book, namely: (Reference Heyne, Gren-Landell, Melvin and Gentle-Genitty1) the multiple needs of young people displaying absenteeism and mental health problems; (Reference Allensworth, Balfanz, Gottfried and Hutt2) a multiple disciplinary approach to responding to these needs and (Reference Fredricks, Parr, Amemiya, Wang and Brauer3) a multi-tiered system of supports for preventing and addressing school absenteeism and mental health problems.

1.2 Mental Health Problems and School Absenteeism

Many young people experience mental health problems. The disturbing extent to which this occurs is observed in international and national studies. A meta-analysis of studies conducted in 27 countries revealed that 13.4% of young people suffered from a mental health disorder at the time of assessment or at some point in the previous 12 months [Reference Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye and Rohde19]. Based on different data, Erskine et al. estimated the global prevalence of mental disorders among young people to range from 3% to 16% depending on the disorder, with a mean prevalence of 7% across all types of disorder (conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorders, eating disorders, depressive disorders and anxiety disorders) [Reference Erskine, Baxter, Patton, Moffitt, Patel and Whiteford20].

Studies also point to an increase in the rate of mental health problems among young people, particularly emotional disorders. In the United States, for example, the percentage of adolescents reporting a major depressive episode in the last 12 months increased from 8.7 in 2005 to 11.3 in 2014 [Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and Han21]. In the United Kingdom, the point prevalence of emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression among 5–15-year-olds increased from 3.9% in 2004 to 5.8% in 2017 [Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus22], and as discussed in Chapter 10 of this book, there is evidence that mental health problems in young people may have further increased during the Covid-19 pandemic. These statistics indicate the extent to which our young people are burdened. One aspect of the burden, emphasised in this book, is school absenteeism. Mental health problems and school absenteeism are linked historically, diagnostically and empirically.

From a historical perspective, attention to the relationship between mental health problems and school absenteeism is nearly as long-standing as attention to the topic of absenteeism itself. In 1913, Jung (cited in Berg [Reference Berg23]) wrote about absenteeism as a disturbance worthy of clinical attention. In 1915, Hiatt hinted at a relationship between absenteeism and behavioural disturbance, referring to the involvement of the juvenile court ‘when chronic truancy or incorrigibility is shown … to secure prompt and regular attendance’ [Reference Hiatt24, p. 7]. In 1932, Broadwin wrote more explicitly about the relationship between absenteeism and mental health problems, referring to ‘a form of truancy … [which] occurs in a child who is suffering from a deep-seated neurosis’ [Reference Broadwin25, p. 254]. Later in the twentieth century the focus on school attendance problems fell from favour among child and adolescent psychiatrists, whereby absenteeism was relegated to a form of impairment accompanying disorders and not deserving attention in its own right [Reference Berg23]. It was also argued that the relegation of school attendance problems ‘may have gone too far’ because they are important indicators of a broad range of current and future problems for young people [Reference Berg23, p. 154].

From a diagnostic perspective, a direct link between mental health problems and school absenteeism appears in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders classification system for mental health disorders [26]. Disorders are diagnosed when symptoms cause impairment in social, occupational or other areas of functioning. For school-aged young people, occupational functioning can be interpreted to mean school functioning, which includes attendance at school. Furthermore, some disorders are defined in part by attendance problems, such as refusal to attend school in separation anxiety disorder and truanting in conduct disorder. An indirect link between mental health problems and absenteeism is found in the criteria for other mental health disorders. For example, social anxiety disorder is predicated upon avoidance of feared social or performance situations or the experience of intense anxiety or distress in these situations. Numerous community-based studies indicate that social anxiety interferes with young people’s schooling, sometimes to the extent that they are unable to attend school [Reference Blöte, Miers, Heyne, Westenberg, Ranta, Marttunen, Garcia-Lopez and La Greca27], which is to be expected given the social nature of the school context. Major depressive disorder includes diagnostic criteria related to fatigue and reduced interest or motivation, which is likely to make school an aversive experience for some depressed young people, increasing the avoidance of school [Reference Wood, Lynne-Landsman, Langer, Wood, Clark and Mark Eddy28]. Young people meeting the criteria for conduct disorder may absent themselves from school as an expression of defiance towards authority [Reference Wood, Lynne-Landsman, Langer, Wood, Clark and Mark Eddy28], and challenging behaviour such as aggression towards peers is a common reason for school exclusion [Reference Macrae, Maguire and Milbourne29].

From an empirical perspective, a wealth of research conducted throughout the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first century addressed associations between absenteeism and mental health problems (see Kearney [Reference Kearney30]). Increasingly, studies are based on large, representative samples which provide stronger evidence for associations between these constructs. However, differences in the way in which researchers examine the association between absenteeism and mental health problems mean that comparing results from two or more studies can still be challenging. For example, some researchers investigated mental health problems among young people with an identified level or type of absenteeism, and in other studies absenteeism was investigated among young people with an identified level or type of mental health problem. Meta-analyses inevitably comprise studies of both types. Much of the research on the association between absenteeism and mental health problems has used cross-sectional data, which means that the temporality and direction of any potential causal relationships between these constructs cannot be established, although causality has occasionally been investigated via longitudinal studies. Next, we present some initial examples of research on absenteeism and mental health problems, with many more examples provided throughout this book.

In an early population-based study, Egger et al. investigated mental health problems among young people in the United States who were displaying school refusal, truancy or both [Reference Egger, Costello and Angold31]. Psychiatric disorders were observed among 25% of young people displaying school refusal and 25% of those displaying truancy, compared with only 7% of young people without a school attendance problem. The study supported the idea that school attendance problems are often associated with internalising and/or externalising mental health problems. When controlling for comorbid psychiatric disorders, school refusal was associated with separation anxiety disorder and depressive disorders and truancy was associated with oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder and depressive disorders. Approaching the topic from a different perspective, Gase et al. found that self-reported truancy (‘cutting or skipping class’) in young people in the United States was greater among those with depression relative to those reporting no depression, even when controlling for other variables (e.g. academic achievement, alcohol and marijuana use) [Reference Gase, Kuo, Coller, Guerrero and Wong32]. A more recent US study points to an association between criminal behaviour by minors and school absenteeism. Robertson and Walker proposed that young people not attending school may engage in unsupervised activities with delinquent peers, leading to involvement with law enforcement [Reference Robertson and Walker33]. They found that chronically absent young people were 3.5 times more likely to be arrested or referred to the justice system than young people who had never been chronically absent. Moreover, chronic absenteeism was a stronger predictor of involvement with the justice system than allegations of child maltreatment.

A study of Norwegian young people examined a range of mental health problems (e.g. internalising behaviour, externalising behaviour, personality problems, substance abuse) associated with various levels of school absenteeism, including no absence (<1.5 days of absence), normal absence (>=1.5 and < 13.5 days of absence) and high absence (>=13.5 days, or 15%) [Reference Ingul, Klöckner, Silverman and Nordahl34]. When individual risk factors were examined, internalising and externalising problems were found to be strongly associated with absenteeism, as were personality problems. When risk factors were studied in relation to each other, externalising behaviour was found to be a main predictor of absenteeism while internalising behaviour was not. Researchers also noted that there were adolescents with internalising problems who were present at school. For example, almost 10% of young people with social anxiety had no absence or normal absence. It was suggested that young people displaying internalising behaviour but still attending school possessed or experienced factors that protected against absenteeism.

Lawrence et al. argued that mental health problems have the potential to influence school attendance and dropout [Reference Lawrence, Dawson, Houghton, Goodsell and Sawyer35]. Furthermore, they contended that absences due to mental health issues could perpetuate poor mental health due to factors such as reduced connectedness and academic achievement, leading to further absenteeism. They examined the impact of different forms of mental health problems on absenteeism, studying attendance among young people with and without common mental disorders. Using data from a national survey of Australian young people, absenteeism was studied as a general construct (i.e. not by type, such as truancy or school refusal). Overall, young people with a mental disorder had higher levels of absenteeism. Furthermore, the primary carers of young people with mental disorders attributed 13% of absences to the mental disorder itself. Reasons for absence due to mental disorders included comorbid physical conditions, suspension or expulsion from school, and peer problems such as bullying. At secondary school, about one-third of females and one-fifth of males with mental disorders missed more than 20 days of school in a year. The authors described this as substantial absence that jeopardises students’ learning and places their mental health at further risk [Reference Lawrence, Dawson, Houghton, Goodsell and Sawyer35].

The findings presented so far were based on associations found in cross-sectional data, limiting inferences about causal pathways between mental health problems and absenteeism. One of the first longitudinal studies was reported by Wood et al. who argued that psychopathology and absenteeism are important risk factors for each other [Reference Wood, Lynne-Landsman, Langer, Wood, Clark and Mark Eddy28]. For example, for some young people absenteeism is an early symptom of anxiety or depression, and the absenteeism then elicits additional symptoms, perhaps presaging worsening absenteeism. For other young people, absence may occur for reasons unrelated to psychopathology but mental health may deteriorate as a result of school absence. Longitudinal data on US young people and sophisticated statistical methods were used to understand reciprocal influences between absenteeism and psychopathology over time. There was ‘at least some support … that a higher level of one of these factors in one year tended to presage the onset of increases in the other factor in the following year’ [p. 362]. There was more evidence of psychopathology leading to absenteeism than the reverse for adolescents compared to children, especially for conduct problems. Longitudinal paths in which absenteeism led to psychopathology were not observed for young people below fifth to sixth grade. Even though absenteeism may not lead to psychopathology in some groups of young people, it likely poses a risk for recovery among young people already experiencing a mental health problem.

Three systematic reviews and meta-analyses have recently been reported. Finning et al. studied the relationship between anxiety and absenteeism, drawing on 11 studies from six countries across North America, Europe and Asia [Reference Finning, Ukoumunne, Ford, Danielson-Waters, Shaw and Romero de Jager36]. There were mixed findings regarding cross-sectional associations between overall anxiety and unexcused absences as well as between types of anxiety and unexcused absences, while two studies suggested a relationship between school refusal and specific anxiety disorders. Finning et al. also explored the relationship between young people’s depression and poor attendance at school, based on 19 studies from eight countries across North America, Europe and Asia [Reference Finning, Ukoumunne, Ford, Danielsson-Waters, Shaw and Romero De Jager37]. They found small-to-moderate cross-sectional associations between depression and total absences and between depression and unexcused absences, as well as moderate-to-large associations between depression and school refusal. The results of two longitudinal studies included in the review suggested an association between young people’s depression and absenteeism 6 or 12 months later, but two other studies provided mixed or no evidence of a longitudinal association. Epstein et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of absenteeism as a factor which could increase risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation, working from the premise that absenteeism is a marker of social exclusion, itself a risk factor for suicidal ideation and self-harm [Reference Epstein, Roberts, Sedgewick, Polling, Finning and Ford38]. Based on a small number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies it was concluded that there is emerging evidence of an association between absenteeism, self-harm and suicidal ideation, although the direction of influence remains unclear. The mechanisms in the association between absenteeism and self-harm or suicidal ideation are also unclear, and the researchers raised the possibility that other factors associated with absenteeism, self-harm and suicidal ideation, such as internalising and externalising disorders and bullying, could explain the associations they found. They also noted that, in a few studies, absenteeism was actually associated with lower risk of suicidal thoughts. One could imagine that some young people who stay at home to avoid bullying might experience a decline in suicidal thoughts.

To a large extent, researchers investigated absenteeism according to broad categories such as excused versus unexcused absenteeism [Reference Finning, Ford, Moore and Ukoumunne39, Reference van den Toren, van Grieken, Mulder, Vanneste, Lugtenberg and de Kroon40] and chronic absenteeism [Reference Lereya, Patel, dos Santos and Deighton41], although there are notable exceptions (e.g. Finning et al. also studied total absences, excused/medical absences, unexcused absences/truancy and school refusal [Reference Finning, Ukoumunne, Ford, Danielson-Waters, Shaw and Romero de Jager36, Reference Finning, Ukoumunne, Ford, Danielsson-Waters, Shaw and Romero De Jager37]). Overall rates of absenteeism camouflage rates per type of absence such as school refusal, truancy and school withdrawal [Reference Davis, Allen-Milton and Coats-Boynton42], and numerous researchers acknowledge this limitation in their work (e.g. [Reference Ingul, Klöckner, Silverman and Nordahl34]). There are various calls for a more nuanced understanding of absenteeism. Lawrence et al. called for the study of associations between mental health problems and absenteeism according to the reason for absenteeism [Reference Lawrence, Dawson, Houghton, Goodsell and Sawyer35], and Van den Toren et al. called for additional examination of mental and physical health quality of life according to specific reasons for absence [Reference van den Toren, van Grieken, Mulder, Vanneste, Lugtenberg and de Kroon40]. Epstein et al. argued that understanding whether different reasons for absence have different effects on risk for self-harm and suicidality would have implications for selecting interventions [Reference Epstein, Roberts, Sedgewick, Polling, Finning and Ford38]. Wood et al. suggested that absences could be classified in ways that show differential associations with psychopathology [Reference Wood, Lynne-Landsman, Langer, Wood, Clark and Mark Eddy28]. In their study of the reciprocal influence of absenteeism and psychopathology, they did not include absences related to school exclusion, despite the widespread over-representation of disciplinary measures such as suspension among minority students and those with special educational needs [Reference Gage, Whitford, Katsiyannis, Adams and Jasper43, Reference McCluskey, Riddell, Weedon and Fordyce44]. Because school exclusion can stem from young people’s behavioural problems, we may find that reciprocal influences between exclusion and mental health problems are greater than for other types of absenteeism such as school withdrawal.

1.3 Promoting Mental Health and School Attendance

The question then arises: is the association between mental health and school attendance merely the inverse of the association between mental health problems and absenteeism? In one respect it could be argued that this is the case, because data on attendance at school is the inverse of absence from school and data on positive mental health reflects the absence of mental health problems. From a practical perspective, however, there is an important difference between ‘school attendance and mental health’ and ‘school absenteeism and mental health problems’. Interventions to promote mental health among young people are different from interventions employed when young people have mental disorder [Reference Fazel, Hoagwood, Stephan and Ford45]. Likewise, interventions to ensure regular school attendance are different from interventions employed when young people have acute absenteeism or severe and chronic absenteeism (see Kearney [Reference Kearney46]).

A key starting point for research on the relationship between school attendance and mental health is to evaluate the impact of interventions to promote attendance (i.e. prevent absence) or to promote mental health (i.e. prevent psychopathology) to see whether they lead, respectively, to continued mental health and to continued regular attendance at school. In the field of substance use, Engberg and Morral found that for each year that young people delayed using drugs or drinking to intoxication, the likelihood of school attendance at follow-up increased by 10% [Reference Engberg and Morral47]. The observed improvements in school attendance were cited as evidence of the cost-effectiveness of substance abuse treatment, given the long-term benefits of being in school. Epstein et al.’s systematic review and meta-analysis, which yielded evidence for an association between school absenteeism and self-harm and suicidal ideation, concluded that there is a need for future research to examine whether improvements in school attendance over time are associated with a reduction in self-harm behaviours [Reference Epstein, Roberts, Sedgewick, Polling, Finning and Ford38]. As more attention is given to evidence-based prevention and early intervention for school attendance problems, as suggested [Reference Tonge and Silverman48], there will be greater opportunity to investigate the relationship between mental health and school attendance.

The chapters in this book help unpack the details important for research and practice aimed at supporting school attendance by promoting mental health and reducing mental health problems, as well as promoting mental health by encouraging school attendance and reducing absenteeism. While reading the chapters, we invite the reader to consider three themes that arise throughout the book: (1) understanding the multiple needs of young people who face various challenges; (2) collaborating in a multiple disciplinary way and (3) employing a multi-tiered system of supports. It is when we understand these needs, collaborate in this way and employ this approach that we can best ensure that school attendance and mental health supplant school absenteeism and mental health problems.

1.3.1 Multiple Needs

Many young people face challenges that may enhance their risk for school absenteeism and mental health problems. Examples of these challenges include poverty; intellectual and developmental disabilities; special educational or medical needs; victimisation, maltreatment or trauma; and other adverse life experiences.

Recent statistics from the UK Department for Education demonstrate that the rate of persistent absence (missing 10% or more of school sessions) is nearly three times higher for the most economically deprived students compared to those who are the least deprived [49]. A similar relationship has also been reported in the United States [Reference Gottfried and Gee50] and Australia [Reference Hancock, Shepherd, Lawrence and Zubrick51]. Research has also revealed that young people living in families with low income or who are in receipt of state benefits are at a greater risk of experiencing a variety of mental health conditions, particularly anxiety, depression and behavioural disorders [Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus22, Reference Lawrence, Dawson, Houghton, Goodsell and Sawyer35, Reference Ghandour, Sherman, Vladutiu, Ali, Lynch and Bitsko52]. According to the 2017 population survey on the mental health of children and young people in England, young people living in households with the lowest levels of income were more than twice as likely to have a mental health condition compared to those with the highest income levels [Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus22].

Young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and those with an identified special educational need have higher rates of absenteeism, have poorer academic attainment and are less likely to complete compulsory education or participate in further education compared to their peers [Reference Andrews, Robinson and Hutchinson53–Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55]. A survey of nearly 5,500 students in Norway indicated that young people with special educational needs were more likely to report that their absence was due to truancy-related reasons (e.g. finding school boring, seeking preferred activities outside of school) than subjective health complaints, somatic symptoms or school refusal [Reference Havik, Bru and Ertesvåg56]. Young people with an intellectual disability or a special educational need are also disproportionately affected by mental health conditions. In the 2017 population survey in England, 47% of those with a recognised special educational need had a mental disorder, compared to 9% of those without a special educational need, and this difference was particularly pronounced for boys [Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus22]. In a systematic review of the association between intellectual disability and mental health disorders, Einfeld et al. demonstrated that young people with an intellectual disability have between 2.8 and 4.5 times the risk of experiencing a mental health disorder compared to those without an intellectual disability, and this does not seem to be influenced by the severity of the intellectual disability [Reference Einfeld, Ellis and Emerson57].

National data from the United States suggests that young people from non-white ethnic backgrounds are more likely to be chronically absent (i.e. absent at least 10% of the time) than their white peers [58]. Specifically, the prevalence of chronic absence was reported to be 20% for Pacific Islanders, 14.6% for African Americans and 10.4% for Native Americans, compared to 9.7% for young people who identified as white. A study by Gage et al. involved data from 94,781 schools from all 50 US states plus the District of Columbia and revealed that black students were also more likely to be permanently excluded from school compared to those from other ethnic groups (10% versus 2.5%) [Reference Gage, Whitford, Katsiyannis, Adams and Jasper43], and a similar trend has been reported in the United Kingdom [Reference Paget, Parker, Heron, Logan, Henley and Emond59]. The prevalence of mental health disorders is also different for young people who belong to different ethnic groups, although this relationship appears to be moderated by the country of study. For example, a recent population survey in the United States demonstrated that non-Hispanic black young people were more likely to be affected by depression and behavioural disorders compared to young people from other ethnic groups, while non-Hispanic whites were the most likely to be affected by anxiety [Reference Ghandour, Sherman, Vladutiu, Ali, Lynch and Bitsko52]. However, recent data from England demonstrates that white young people are almost three times more likely to have a mental disorder (14.9%) compared to black (5.6%) and Asian (5.2%) young people, and this trend is found consistently across all types of disorder [Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus22].

Some of the mechanisms through which the aforementioned risk factors may affect school attendance and mental health include fewer family resources, parental stress and the developmental context to which young people are exposed [Reference Gottfried and Gee50, Reference Chaudry and Wimer60]. Those from higher risk groups also have higher levels of many of the known risk factors for absenteeism and mental health problems, including a greater prevalence of chronic physical conditions, higher healthcare utilisation, sleep problems and peer victimisation and poorer academic functioning [Reference Andrews, Robinson and Hutchinson53, Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55, Reference Boulet, Boyle and Schieve61].

Risk factors for school absence and poor mental health rarely occur in isolation. Some researchers have suggested that it is the total number of risk factors, as well as unique combinations of risk factors, that most strongly predict difficulties in either of these domains [Reference Ingul, Klöckner, Silverman and Nordahl34, Reference Gottfried and Gee50, Reference Eriksson, Ghazinour and Hammarström62, Reference Maynard, Vaughn, Nelson, Salas-Wright, Heyne and Kremer63]. Maynard et al.’s exploration of the correlates of truancy is illustrative [Reference Maynard, Vaughn, Nelson, Salas-Wright, Heyne and Kremer63]. In a national survey involving over 200,000 young people in the United States, they found that the association of truancy with both household income and smoking/drug use was different for individuals belonging to different ethnic groups. For example, low income was a greater predictor of truancy for black and non-Hispanic white young people than for Hispanic young people, while smoking/drug use was associated with higher odds of truancy only for non-Hispanic white young people. Gottfried and Gee found that students in the lowest socio-economic group who also had a disability were less likely to be chronically absent than those in the lowest socio-economic group who did not have a disability, which the authors suggested might be because schools provide access to specialist disability services that low socio-economic families might not otherwise be able to afford [Reference Gottfried and Gee50]. Burton et al. explored the relationships between mental health, absenteeism and sexual minority status in a sample of 14–19-year-olds in the United States and found that depression and anxiety were more predictive of unexcused absences for sexual minority compared to heterosexual young people, but these mental health problems did not differentially affect the number of excused absences [Reference Burton, Marshal and Chisolm64].

These examples demonstrate the complexity of difficulties with mental health and attendance at school, highlighting the need to consider a wide range of potential risk factors across different domains and how these factors interact. In the 2018 Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development, Patel et al. [Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton65] emphasised ‘a convergent model of mental health, recognising the complex interplay of psychosocial, environmental, biological and genetic factors across the life-course, but in particular during the sensitive developmental periods of childhood and adolescence’ (p. 1556). Recent attempts to develop models of absenteeism based on bioecological systems offer a helpful framework to explore the complexity of the problem in a way that is inclusive of all students [Reference Gottfried and Gee50, Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55]. One example is the Kids and Teens at School (KiTeS) framework, which is a multifactorial approach to understanding school attendance problems based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory of child development [Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55]. This framework enables a deeper understanding of the role of individual, parental, familial, environmental and broader societal and cultural factors in school attendance problems, as well as considering the complex interactions among these factors. The KiTeS model has the potential to inform research on the development, maintenance and alleviation of school attendance problems among all students, including those from high-risk groups. For further information about the KiTeS framework, we refer readers to the excellent open-access publication prepared by Melvin et al. [Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55].

Although there are well-established links between school absence, poor mental health and the risk factors discussed in this section, little research has explored what can be done to best support young people who face these additional challenges and improve their educational and mental health outcomes. While school absence is harmful to academic functioning for all students, it may be particularly damaging to those from disadvantaged populations, so early identification and intervention may be especially critical for these students [Reference Hancock, Shepherd, Lawrence and Zubrick51].

The impact of the aforementioned challenges on mental health and attendance at school is addressed throughout this book. For example, Chapter 6 explores some of the difficulties faced by young people who have experienced an acquired brain injury and the impact this may have on mental health and attendance at school. Chapter 7 discusses the role of school factors on mental health and attendance at school, with particular attention to the difficulties faced by young people with special educational needs. Chapter 8 considers the issues faced by young people from vulnerable groups, with a particular focus on looked after children and refugees.

1.3.2 Multiple Disciplinary Collaboration

A multiple disciplinary approach to collaboration can be multi-disciplinary or interdisciplinary [Reference Choi and Pak66]. The multi-disciplinary or ‘additive’ approach occurs when professionals from more than one discipline (e.g. education and psychology) share their knowledge but stay within their boundaries, whereas the interdisciplinary or ‘interactive’ approach occurs when professionals analyse, synthesise and harmonise the links between their disciplines into a coherent whole [Reference Choi and Pak66]. Based on these descriptions, one could imagine that a meeting of professionals (e.g. a teacher, school administrator, social worker and psychologist) to share perspectives on a young person’s absenteeism represents multi-disciplinary collaboration, whereas an effort by these same professionals to develop an integrated school-community intervention for absenteeism represents interdisciplinary collaboration. In this chapter we use ‘multiple disciplinary’ to refer to collaboration which is multi-disciplinary and/or interdisciplinary in nature.

Multiple disciplinary collaboration is needed because real-world problems are often complex and not confined to the artificial boundaries of disciplines [Reference Choi and Pak66]. Indeed, the multifactorial, multi-level models for understanding attendance and absence [Reference Gottfried and Gee50, Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55] and intervening with absenteeism [Reference Lyon and Cotler67, Reference Nuttall and Woods68] point to the complex interactions among multiple factors within and across systems (e.g. family, school and community). As noted by Choi and Pak [Reference Choi and Pak66], to understand and solve complex problems we need the perspectives of professionals who see things differently, establish fresh research questions, achieve sophisticated interpretation of results, derive consensus definitions and guidelines, and provide comprehensive services. For this to occur, professionals seeking to promote school attendance and mental health need to be mindful of the distal and proximal factors influencing the likelihood and extent of multiple disciplinary collaboration.

Distal factors influencing collaboration include economic resources, government policies, education and healthcare systems, and changes in these factors over time. In the United States, for example, local and state variations in services available via school-based health centres (SBHCs) are influenced by financing, which can come from local and state funds, reimbursement from insurance companies and/or federal grants [Reference Graves, Weisburd, Salem, Gottfried and Hutt69]. There is an emerging consensus among education professionals in the United States about the role SBHCs can play in enhancing the integration of services, whereby SBHCs represent ‘a nodal point for assessing multiple risk and protective factors associated with truancy, including school connectedness, academic engagement, depression management, and substance abuse prevention’ [Reference Gase, Kuo, Coller, Guerrero and Wong32, p. 49]. With respect to distal factors impacting multiple disciplinary work in the United Kingdom, the government recently presented a strategic policy for better integration between education and health services for the provision of mental health support to young people, including a greater role for schools in identification, prevention and management [Reference Epstein, Roberts, Sedgewick, Polling, Finning and Ford38]. As to the question of funding, Epstein et al. suggested that this will become less complex when policy-makers recognise that schools are often the ‘de facto front line mental health service for young people’ [Reference Epstein, Roberts, Sedgewick, Polling, Finning and Ford38].

Proximal factors influencing collaboration include professionals’ beliefs about the importance of multiple disciplinary work and about their role in that work. For example, some education professionals ascribe absenteeism to parental attitudes and the home environment (e.g. [Reference Malcolm, Wilson, Davidson and Kirk5]), likely stifling their collaboration in the development or delivering of interventions to address absenteeism. In the case of school withdrawal (i.e. parents keeping a child at home), it may be true that parents’ attitudes and behaviours have a large influence on the child’s attendance, but cases of truancy, school refusal and school exclusion may stem from factors that education professionals can influence, such as academic difficulties [Reference Havik, Bru and Ertesvåg56], bullying [Reference Egger, Costello and Angold31] and overuse of suspension among young people with special educational needs [Reference Gage, Whitford, Katsiyannis, Adams and Jasper43], respectively. For all types of school attendance problem, including school withdrawal, there are many interventions available to education professionals to prevent or reduce absenteeism (e.g. [Reference Kearney46, Reference Epstein and Sheldon70]). However, it is necessary to firstly overcome the long-standing belief ‘that it is the school’s responsibility to teach those students who attend and that it is the responsibility of families and the students themselves to do what is needed to attend school regularly’ [Reference Allensworth, Balfanz, Gottfried and Hutt2, p. x].

When education professionals view attendance as an outcome of the school’s policies and practices, this can have an important influence on what schools do to support and improve attendance [Reference Hough, Gottfried and Hutt17]. Indeed, experience and qualitative studies (e.g. [Reference Finning, Harvey, Moore, Ford, Davies and Waite71]) reveal that many education professionals are highly committed to helping young people attend school (e.g. home visits, providing emotional support and making adaptations at school) and supporting parents in this endeavour. The beliefs of mental health professionals will similarly influence the way in which they collaborate with professionals from other disciplines to address absenteeism.

The nature of multiple disciplinary collaboration – ‘which partners?’ – and the extent of collaboration – ‘how much time and money are invested by each partner?’ – can vary on a case-by-case basis or be established in ongoing arrangements between professionals from different disciplines and organisations. Distal and proximal factors at national and local levels will shape the ways in which ongoing arrangements and case-by-case collaboration occur. Case-by-case collaboration may occur, for example, when a privately practising psychologist convenes a meeting with the teachers of a young person receiving treatment from the psychologist to discuss ways to help the student return to school. A simple form of ongoing collaboration is the provision of mental health services via a counsellor or psychologist employed by the school. This person can support school staff with prevention interventions (e.g. conducting parent information sessions focusing on the importance of attendance), provide individual support to young people showing signs of an emerging school attendance problem and liaise with external services in cases of severe and chronic absenteeism. Another relatively simple form of ongoing collaboration is observed in an intervention to reduce truancy and antisocial behaviour, whereby school representatives and police collaborate during family group conferences held with truanting young people and their parental guardians [Reference Mazerolle, Antrobus, Cardwell, Piquero and Bennett72]. Consensus-based dialogue is used to harmonise the way in which a police officer and school representative engage with the truanting young person and socialise their views about obeying the law, including the legal requirements associated with school attendance.

More complex collaborations are presented in a recent issue of Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, which includes Dutch, Australian and German interventions for school refusal and other attendance problems. The interventions reflect established collaboration between education and mental health systems [Reference Brouwer-Borghuis, Heyne, Sauter and Scholte73, Reference McKay-Brown, McGrath, Dalton, Graham, Smith and Ring74] and a multiple disciplinary approach to designing and delivering treatment [Reference Reissner, Knollmann, Spie, Jost, Neumann and Hebebrand75]. Another recent study in the United States examined associations between maltreatment, education and involvement in the justice system, highlighting the value of policy which keeps young people, especially African American boys who have been involved with child protection services, in the classroom rather than suspending them for problematic behaviour under a zero-tolerance policy [Reference Robertson and Walker33]. The authors called for trauma-informed practice in the school setting, exemplifying a multiple disciplinary effort to address young people’s mental health and school attendance.

In the United States, the SBHCs referred to earlier are another example of ongoing arrangements between professionals from multiple disciplines. Young people and sometimes family members are provided with physical and mental health services on the school site via professionals such as nurse practitioners, paediatricians, dentists and licensed therapists. In the United Kingdom, changes have recently been made to government policy to improve mental health and wellbeing support in schools. The changes include the introduction of education mental health practitioners who deliver evidence-based mental health interventions to young people in schools; encouragement for all schools to have a designated senior lead for mental health who oversees the school’s approach to mental health; and initiation of a training scheme entitled the Link Programme, in which a staff member from every school is offered training alongside mental health specialists [76, 77].

These services help reduce the need for young people to miss school for healthcare appointments. Improvements in health may yield improvements in school attendance, although there is limited empirical support for the role SBHCs play in reducing absenteeism, and furthermore, the frameworks for how SBHCs are implemented include few measures specifically designed to reduce absenteeism [Reference Graves, Weisburd, Salem, Gottfried and Hutt69]. One function SBHCs could serve in the reduction of absenteeism, indirectly, is to offer what Fox, Halpern and Forsyth (2008) refer to as school-based mental health check-ups for young people. School attendance researchers advocate school-wide screening of young people (e.g. [Reference Ingul, Havik and Heyne78]) and education for school staff about the use of attendance data (e.g. [Reference Finning, Ukoumunne, Ford, Danielson-Waters, Shaw and Romero de Jager36, Reference Finning, Ukoumunne, Ford, Danielsson-Waters, Shaw and Romero De Jager37]) to identify students at risk of mental health problems and those already displaying symptoms in order to increase early intervention. Wroblewski et al. similarly recommended screening of social-emotional strengths to identify young people at risk for high levels of truancy [Reference Wroblewski, Dowdy, Sharkey and Kyung79]. Counsellors working in school settings might promote social and emotional development by working with groups of students or entire classrooms or helping teachers develop and deliver lessons on this topic [Reference Reback80].

Throughout this book the reader will find many references to multiple disciplinary work. In Chapter 3, for example, Finning and Dubicka underscore the role schools can play in the identification and prevention of and intervention for young people’s emotional difficulties, via collaboration (e.g. educational professionals, GPs, mental health professionals and parents), a whole-school approach to mental health aided by a pastoral support team and options for early referral to specialist services for emotional disorders and/or school attendance problems. In Chapter 4, Parker et al. emphasise the importance of multimodal interventions in response to many behavioural difficulties seen in school settings. They also note the importance of holistic assessment that considers school attendance and involves a multi-agency approach. In Chapter 5, Russell writes about absenteeism among young people with neurodevelopmental disorders, noting that the basis for responding to their special educational needs is the development of a support team that might include mental health professionals. Emphasis is placed on fostering close contact between schools and parents, as well as linking parents with social care or other services as needed. In Chapter 9, one of the themes emerging from a parent’s experience is the lack of consistency in advice received from different professionals, highlighting a need for better communication and collaboration among those involved in supporting families affected by absenteeism.

1.3.3 Multi-tiered System of Supports

As noted earlier in this chapter, a key starting point for research and practice in school attendance and mental health surrounds interventions designed to promote attendance, prevent absenteeism and address extant school attendance problems. A main challenge in this area, however, is the sheer number of interventions that have been designed for these purposes. The volume of prevention- and intervention-based practices can be overwhelming to clinicians, school officials, parents and other stakeholders closely involved with this population.

One framework that may be helpful for conceptualising and organising the myriad practices available for school attendance and its problems involves a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS). MTSS is a service delivery model that includes clusters of assessment and intervention strategies specifically matched to student needs across various domains [Reference Stoiber, Gettinger, Jimerson, Burns and van der Heyden81]. Key tenets of MTSS include an emphasis on prevention, a tiered continuum of interventions based on the level of support required for a student, early warning systems and regular screening, evidence-based practices, data-based problem-solving and decision-making, fidelity of implementation, and natural incorporation into available school improvement plans [Reference McIntosh and Goodman82]. MTSS models are heavily based on tiers of intervention that include universal or primary prevention practices to promote adaptive behaviour, selective intervention or secondary prevention practices to address emerging problems and intensive intervention or tertiary prevention practices to address chronic and severe problems [Reference Lewis, McIntosh, Simonsen, Mitchell and Hatton83]. Schools in many locations are now a key provider of mental health support and have thus been drawn to MTSS models to maximise resources [Reference Kincaid, Dunlap, Kern, Lane, Bambara and Brown84].

MTSS models to date have primarily focused on academics, behaviour and life skills [Reference Shogren, Wehmeyer and Lane85]. Response to Intervention, for example, is a service delivery model whereby all students initially receive high-quality universal core instruction and are frequently screened for difficulties in academic areas such as reading. Extra levels of support are then proactively provided for students struggling with certain subjects, thus moving away from a traditional ‘wait to fail’ approach [Reference McIntosh and Goodman82]. In related fashion, positive behavioural intervention and support is a multi-tiered model designed to promote respectful behaviour and reduce disruptive or other inappropriate behaviour [Reference Sugai and Horner86]. Other multi-tiered approaches, such as social and emotional learning, are designed to enhance core competencies such as interpersonal skills and adaptive life choices [Reference Bradshaw, Bottiani, Osher, Sugai, Weist, Lever, Bradshaw and Owens87]. In recent years, MTSS models have been extended to mental health problems such as anxiety [Reference Jones, West and Suveg88, Reference Weist, Eber, Horner, Splett, Putnam and Barrett89], depression [Reference Arora, Collins, Dart, Hernández, Fetterman and Doll90], trauma [Reference Reinbergs and Fefer91], suicide prevention [Reference Singer, Erbacher and Rosen92], ADHD [Reference Fabiano and Pyle93], aggression and defiance [Reference Waschbusch, Breaux and Babinski94], autism spectrum disorder [Reference Sansosti95] and mental health needs among homeless young people [Reference Sulkowski and Michael96].

In 2014 Kearney and Graczyk initially outlined a multi-tiered approach to promote school attendance and to reduce school absenteeism utilising the Response to Intervention model [Reference Kearney and Graczyk97]. This particular model was chosen because academic performance and school attendance are very closely associated, because many school-based practices such as functional assessment link well to the school attendance literature and because empirical studies of Response to Intervention often include school attendance and its problems as outcome measures [Reference Chen, Culhane, Metraux, Park and Venable98–Reference Prewett, Mellard, Deshler, Allen, Alexander and Stern100].

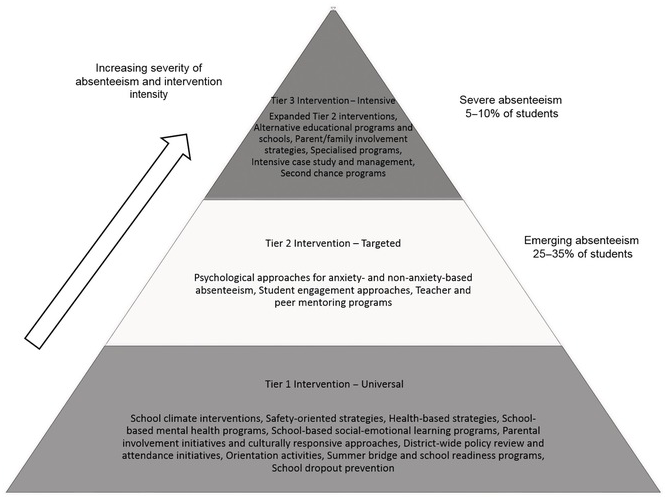

In this original model, Kearney and Graczyk arranged various prevention efforts and intervention practices into multiple tiers [Reference Kearney and Graczyk97]. The tiers were meant to reflect changes in absenteeism severity, contextual risk factors and complexity of interventions that would be expected to accumulate as an attendance problem worsened (see Figure 1.1). Tier 1 interventions, or preventative practices, are those typically implemented on a school-wide basis to broadly promote school attendance rates. These interventions thus included measures to enhance school safety and overall climate, to develop social and emotional competencies, to boost physical and mental health, to increase parent involvement at school, to be more responsive to cultural and language differences between school faculty and parents and to augment academic, career and adult readiness. Such practices were associated with assessment recommendations that included ongoing evaluation of attendance data, identification of early warning signs of school absenteeism and course grades, among other pertinent data.

Tier 2 interventions are those typically designed to address acute problems and are thus selectively targeted towards certain students, in this case those with school attendance problems of a mild to moderate severity. These interventions thus included clinically based strategies for young people with anxiety-based and non-anxiety-based absenteeism, student school engagement approaches and various types of mentoring programmes. Tier 2 assessment practices are wide-ranging and can include interviews, observational data, functional analysis and review of academic, attendance and other pertinent records.

Tier 3 interventions are those typically designed to address more chronic problems and are thus intensively targeted towards students with very severe school attendance problems. These interventions included alternative educational pathways, second chance programmes, intensive case management and therapeutic approaches to enhance parent and family involvement as well as to address severe psychopathology. Tier 3 assessment practices may be more specialised given the unique circumstances and history of a given case at this level and can thus involve a comprehensive case study analysis and input from multiple agencies [Reference Kearney46].

Since the publication of Kearney and Graczyk’s Response to Intervention model, service delivery systems, particularly those in schools, have undergone several seismic shifts in focus. Many of these delivery systems are now more integrated in nature to conserve limited resources and to concurrently address multiple domains of functioning [Reference Weist, Eber, Horner, Splett, Putnam and Barrett89]. In addition, as noted earlier, multi-tiered service delivery models within schools have increasingly become more tailored to specific mental health and other challenges faced by students. Another key shift has been to consider more multi-dimensional perspectives, for example in a multi-sided pyramidal fashion, so that various domain clusters of a given problem can be addressed at the same time [Reference Kearney and Graczyk101]. For example, tier-based strategies could be uniquely tailored to students in different school levels. In the multi-sided pyramidal approach, prevention remains a priority no matter the domain that is addressed, early warning system development is strongly encouraged, and the multi-dimensional structure can be easily tailored to different domain clusters surrounding a given problem, such as school absenteeism.

With respect to the latter, Kearney and Graczyk (2019) outlined suggestions for a multi-dimensional multi-tiered approach that could be tailored to various domain clusters associated with attendance problems. Sample domain clusters included (Reference Heyne, Gren-Landell, Melvin and Gentle-Genitty1) typological constructs, (Reference Allensworth, Balfanz, Gottfried and Hutt2) functional distinctions, (Reference Fredricks, Parr, Amemiya, Wang and Brauer3) school levels, (Reference Zaff, Donlan, Gunning, Anderson, McDermott and Sedaca4) severity points and (Reference Malcolm, Wilson, Davidson and Kirk5) ecological stages. As noted earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 2, for example, important typological constructs in this area include school refusal, truancy, school withdrawal and school exclusion [Reference Heyne, Gren-Landell, Melvin and Gentle-Genitty1]. In a multi-dimensional MTSS approach, each side of a four-sided pyramid could be populated with each of these constructs, and tier-based assessment and intervention recommendations could then be explicated for each.

The number of sides of a multi-dimensional pyramid could vary according to the number of domains addressed in the other clusters. In a functional approach, for example, there could be four pyramid sides that include young people who (Reference Heyne, Gren-Landell, Melvin and Gentle-Genitty1) avoid school-based stimuli that provoke a general sense of negative affectivity, (Reference Allensworth, Balfanz, Gottfried and Hutt2) escape aversive social and/or evaluative situations at school, (Reference Fredricks, Parr, Amemiya, Wang and Brauer3) seek attention from significant others such as parents and (Reference Zaff, Donlan, Gunning, Anderson, McDermott and Sedaca4) pursue tangible rewards outside of school [Reference Kearney102]. Multi-tiered approaches could also be uniquely designed for schools with low-, moderate- and high-severity absenteeism rates or for educational centres at preschool, elementary, middle and high school levels [Reference Kearney and Graczyk101, Reference Hobbs, Kotlaja and Wylie103]. Such approaches could also be tailored to a perspective of school attendance problems across ecological stages or spheres of influence [Reference Melvin, Heyne, Gray, Hastings, Totsika and Tonge55].

Multi-tiered system of support models remain in development but offer a potential pathway towards reconciling various approaches to school attendance problems while simultaneously focusing on the development of best practices for assessment and intervention. The models allow for a common language among clinicians, researchers, school officials and others and can be tailored to the unique needs and resources of a specific school, jurisdiction or culture. In addition, the models are amenable to implementation strategies that have been developed for educational agencies and could be modified as needed given anticipated rapid changes in education and technology.

The benefits of an MTSS approach for young people who are struggling with mental health and attendance at school are alluded to in other parts of this book. For example, in Chapter 3 Finning and Dubicka describe evidence for the effectiveness of multi-tiered school-based interventions for young people with emotional difficulties, combining universal preventative interventions delivered to all students with indicated or targeted interventions for those with established difficulties or who are identified as being at risk. In Chapter 5, Russell highlights the importance of examining young people’s response to intervention through regular monitoring and review of progress and basing decisions on the implementation of further interventions on the young person’s response to those already tried.

1.4 Conclusion

The chapters in this book constitute a timely assimilation of age-old wisdom and cutting-edge research and practice in the realms of mental health and school attendance. They help meet the need for a broad yet nuanced understanding of the relationship between mental health problems and absenteeism and between mental health and school attendance. The abundance of data and ideas will help to take research and practice forward at a greater pace and with greater sophistication than before. Ideally, more longitudinal studies will examine reciprocal relationships between mental health problems and absenteeism and between mental health and attendance, accounting for broad distinctions in absenteeism (e.g. chronic and non-chronic) together with finer distinctions in absenteeism (e.g. school refusal, truancy, school withdrawal and school exclusion). The current chapter provides a multi-dimensional multi-tiered approach that could benefit research of this kind.

As you read the chapters in this book, we invite you to bear in mind the multiple needs of young people with mental health problems and absenteeism, the options for multiple disciplinary collaboration to address their needs and the benefits of employing a multi-tiered approach when investigating and addressing those needs.