Book contents

- Inconsistency in Linguistic Theorising

- Inconsistency in Linguistic Theorising

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Abbreviations and central terms

- 1 Introduction

- Part I The State of the Art

- Part II Paraconsistency

- Part III Plausible Argumentation

- Part IV Summary

- References

- Index

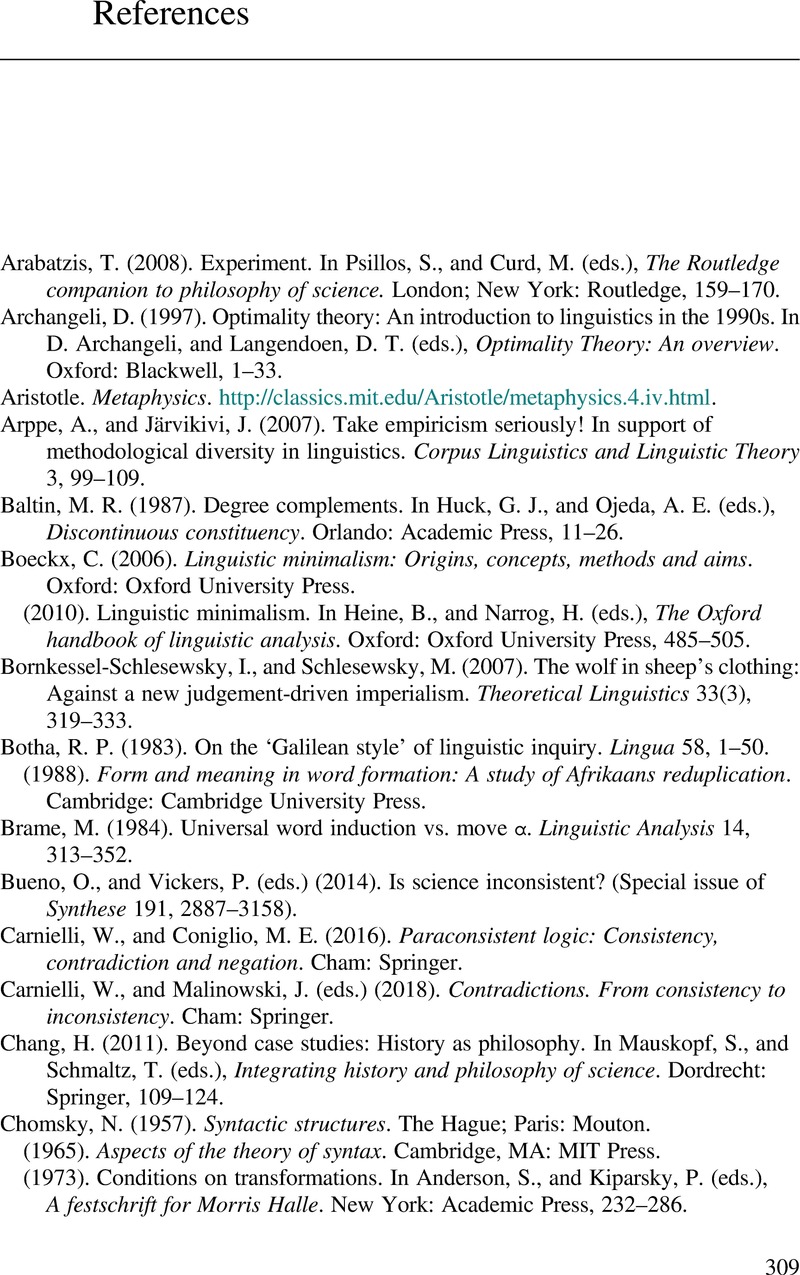

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2022

- Inconsistency in Linguistic Theorising

- Inconsistency in Linguistic Theorising

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Abbreviations and central terms

- 1 Introduction

- Part I The State of the Art

- Part II Paraconsistency

- Part III Plausible Argumentation

- Part IV Summary

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Inconsistency in Linguistic Theorising , pp. 309 - 316Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022