Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- The Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-Bard Stage Career of John Barrymore

- 2 Dangerously Modern: Shakespeare, Voice, and the “New Psychology” in John Barrymore's “Unstable” Characters

- 3 The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes

- 4 John Barrymore's Introspective Performance in Beau Brummel

- 5 “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

- 6 From Rome to Berlin: Barrymore as Romantic Lover

- 7 The Power of Stillness: John Barrymore's Performance in Svengali

- 8 Prospero Unbound: John Barrymore's Theatrical Transformations of Cinema Reality

- 9 A Star is Dead: Barrymore's Anti-Christian Metaperformance

- 10 Handling Time: The Passing of Tradition in A Bill of Divorcement

- 11 John Barrymore's Sparkling Topaze

- 12 “Planes, Motors, Schedules”: Night Flight and the Modernity of John Barrymore

- 13 Barrymore and the Scene of Acting: Gesture, Speech, and the Repression of Cinematic Performance

- 14 “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

- 15 Barrymore Does Barrymore: The Performing Self Triumphant in The Great Profile

- Works Cited

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- The Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-Bard Stage Career of John Barrymore

- 2 Dangerously Modern: Shakespeare, Voice, and the “New Psychology” in John Barrymore's “Unstable” Characters

- 3 The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes

- 4 John Barrymore's Introspective Performance in Beau Brummel

- 5 “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

- 6 From Rome to Berlin: Barrymore as Romantic Lover

- 7 The Power of Stillness: John Barrymore's Performance in Svengali

- 8 Prospero Unbound: John Barrymore's Theatrical Transformations of Cinema Reality

- 9 A Star is Dead: Barrymore's Anti-Christian Metaperformance

- 10 Handling Time: The Passing of Tradition in A Bill of Divorcement

- 11 John Barrymore's Sparkling Topaze

- 12 “Planes, Motors, Schedules”: Night Flight and the Modernity of John Barrymore

- 13 Barrymore and the Scene of Acting: Gesture, Speech, and the Repression of Cinematic Performance

- 14 “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

- 15 Barrymore Does Barrymore: The Performing Self Triumphant in The Great Profile

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

When at 10.20 p.m., May 29, 1942, he died at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital in the company of his brother Lionel, his lifelong friend Gene Fowler, John Decker, and the actor Alan Mowbray, John Barrymore was only sixty years old. His liver and kidneys ravaged by alcoholism, he had been partially comatose for seventy-two hours. The Los Angeles Times saw fit to mount him to its topmost headline, “John Barrymore Taken by Death,” an elevation that allowed him posthumously to supersede George Marshall's planned invasion of France. That he was imagined to have been “taken by Death” rather than, less Olympically, dying as mortals do, signals the monumental quality of the regard in which he was held by those who admired him. This was not merely a “great performer,” not merely an onstage and onscreen presence shining with all the brilliance of astute training and preparation for an august craft; it was an almost superhuman being who, in the end, had to be reached out for and seized away, so tenaciously did his spirit and courage hold on to his wounded living force. In “taking” Barrymore, Death was stealing from us all.

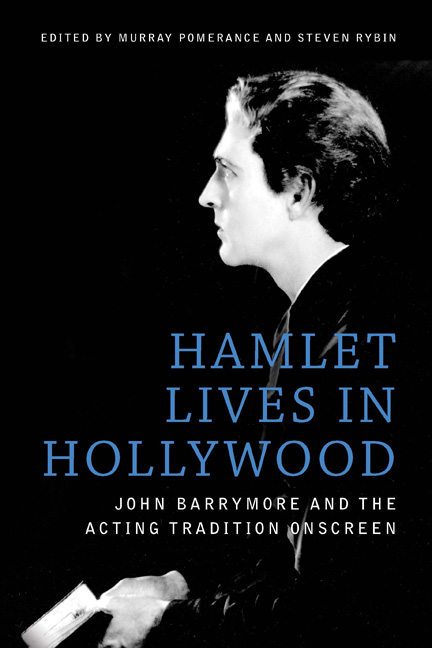

He picked up the nickname “The Great Profile” (around the time of Beau Brummel), a tag with resonance. After all, any part of a body might gain prominence in imagery: Georgia O'Keefe's hands in the photography of Alfred Stieglitz; Fred Astaire's feet. And, as to faces, any screen actor might choose to suggest or request that the cameraman bias his view to one side: no one's face has two identical sides, and it is to the actor's career benefit that he take steps to ensure, as much as possible, an appealing view for potential ticket buyers’ ongoing fascination. But other actors, turning only one side to the camera (a celebrated case was Claudette Colbert), did not (and do not) get named a “great profile,” they are merely seen in profile, and to better effect. Barrymore was being coined. In the deep thoughts of his viewers, he was receiving the respect and adoration that had also bathed the identity of the Roman emperors, and that for Barrymore was iconized even while he lived on coinage of his own country. Barrymore, of course, lived far from Rome, to be categorically correct in Benedict Canyon, that is, Beverly Hills, not Hollywood.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Hamlet Lives in HollywoodJohn Barrymore and the Acting Tradition Onscreen, pp. 1 - 9Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017