Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- The Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-Bard Stage Career of John Barrymore

- 2 Dangerously Modern: Shakespeare, Voice, and the “New Psychology” in John Barrymore's “Unstable” Characters

- 3 The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes

- 4 John Barrymore's Introspective Performance in Beau Brummel

- 5 “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

- 6 From Rome to Berlin: Barrymore as Romantic Lover

- 7 The Power of Stillness: John Barrymore's Performance in Svengali

- 8 Prospero Unbound: John Barrymore's Theatrical Transformations of Cinema Reality

- 9 A Star is Dead: Barrymore's Anti-Christian Metaperformance

- 10 Handling Time: The Passing of Tradition in A Bill of Divorcement

- 11 John Barrymore's Sparkling Topaze

- 12 “Planes, Motors, Schedules”: Night Flight and the Modernity of John Barrymore

- 13 Barrymore and the Scene of Acting: Gesture, Speech, and the Repression of Cinematic Performance

- 14 “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

- 15 Barrymore Does Barrymore: The Performing Self Triumphant in The Great Profile

- Works Cited

- Index

14 - “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- The Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-Bard Stage Career of John Barrymore

- 2 Dangerously Modern: Shakespeare, Voice, and the “New Psychology” in John Barrymore's “Unstable” Characters

- 3 The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes

- 4 John Barrymore's Introspective Performance in Beau Brummel

- 5 “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

- 6 From Rome to Berlin: Barrymore as Romantic Lover

- 7 The Power of Stillness: John Barrymore's Performance in Svengali

- 8 Prospero Unbound: John Barrymore's Theatrical Transformations of Cinema Reality

- 9 A Star is Dead: Barrymore's Anti-Christian Metaperformance

- 10 Handling Time: The Passing of Tradition in A Bill of Divorcement

- 11 John Barrymore's Sparkling Topaze

- 12 “Planes, Motors, Schedules”: Night Flight and the Modernity of John Barrymore

- 13 Barrymore and the Scene of Acting: Gesture, Speech, and the Repression of Cinematic Performance

- 14 “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

- 15 Barrymore Does Barrymore: The Performing Self Triumphant in The Great Profile

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

No one can watch—and listen to—John Barrymore in Howard Hawks's Twentieth Century and fail to recognize that his is a stupendous performance. With every physical gesture, facial expression, and vocal inflection, he marshals unexcelled acting technique, control, and timing to “nail” the charismatic, monstrous, yet strangely likable Oscar Jaffe. Oscar is always playing to an audience, not striving to make himself intelligible to others—or to himself. Drawing on knowledge gleaned from the theater—not the world's—stage, he is forever passing off as spontaneous lines of dialogue and behavior he scripts for himself to use, to his advantage, in his everyday life. He lives as if he were the star in a play he is writing, producing, and directing.

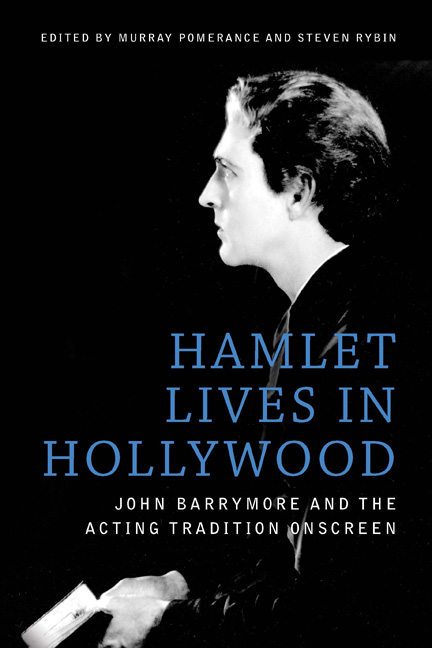

Sometimes, he acts so as to pass himself off as a man simply being himself, as at the train station, by disguising himself as a veritable Colonel Sanders to fool the detectives on the lookout for him (see Figure 1). At other times, the acting strives for melodramatic effect, as when he tries to convince Lily Garland, née Mildred Plotka (Carole Lombard), that, if she leaves him alone to go to a party, he will kill himself. (Many Barrymore characters, such as Hamlet, are subject to melancholy so profound that, at some point, they contemplate—or even commit—suicide.) At his most theatrical, demanding the spotlight, Oscar acts as if the play of his life has the gravitas, the elevated poetic language, of Shakespearean tragedy. He is this way every time he fires his right-hand man Oliver Webb (Walter Connolly) by pronouncing sentence on him, declaiming in a portentous voice and with a grand sweep of his arm, “I close the iron door!” Or when, his glazed eyes looking past Oliver as if captivated by a vision of another world, he says that, in the Passion Play he imagines himself producing, he has “at last found a story that is worthy” of Lily. Or when he says to Lily that the play will climax with her delivering “one of the greatest speeches in the history of literature.” Or when, after acting his way past the detectives, he declares, in a grandiloquent voice, “I never thought I should sink so low as to become an actor.”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Hamlet Lives in HollywoodJohn Barrymore and the Acting Tradition Onscreen, pp. 169 - 182Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017