Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Global Imaginaries and Performance in Asia

- 2 Globalizing the Imagination: Introductory Reflections

- 3 Weddings, Yoga, Hook-ups: Performed Identities and Technology in Bali

- 4 Super Premium Soft Double Vanilla Rich and the Ideal of Convenience in Japan

- 5 Unearthing the Past and Re-imagining the Present: Contemporary Art and Muslim Politics in a Post-9/11 World

- 6 Keeping Communists Alive in Singapore

- 7 Performative Pedagogies: Lifestyle Experts on Indian Television

- 8 Performing Cities: The Philippines Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai International Exposition

- 9 Mobile Performance and the In-between: Yogyakarta Comes to Melbourne

- 10 An Islamist Flash Mob in the Streets of Shah Alam: Unstable Genres for Precarious Times

- 11 Pure Love?: Sanitized, Gendered and Multiple Modernities in Chinese Cinemas

- 12 Yogya on Stage

- Index

5 - Unearthing the Past and Re-imagining the Present: Contemporary Art and Muslim Politics in a Post-9/11 World

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 December 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Global Imaginaries and Performance in Asia

- 2 Globalizing the Imagination: Introductory Reflections

- 3 Weddings, Yoga, Hook-ups: Performed Identities and Technology in Bali

- 4 Super Premium Soft Double Vanilla Rich and the Ideal of Convenience in Japan

- 5 Unearthing the Past and Re-imagining the Present: Contemporary Art and Muslim Politics in a Post-9/11 World

- 6 Keeping Communists Alive in Singapore

- 7 Performative Pedagogies: Lifestyle Experts on Indian Television

- 8 Performing Cities: The Philippines Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai International Exposition

- 9 Mobile Performance and the In-between: Yogyakarta Comes to Melbourne

- 10 An Islamist Flash Mob in the Streets of Shah Alam: Unstable Genres for Precarious Times

- 11 Pure Love?: Sanitized, Gendered and Multiple Modernities in Chinese Cinemas

- 12 Yogya on Stage

- Index

Summary

Abstract

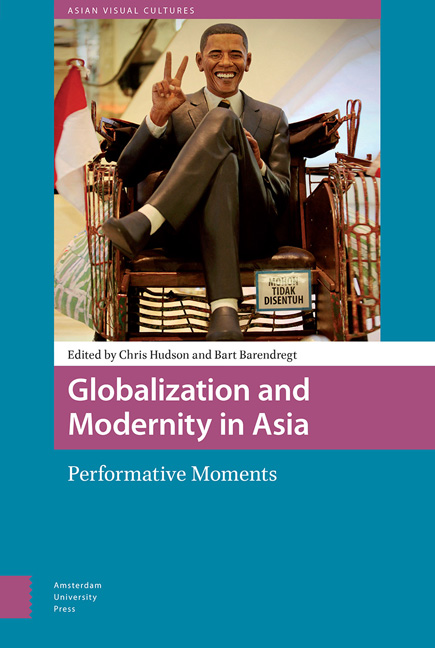

Contemporary Indonesian art shows how visual culture is a site of (Muslim) politics, creativity, contestation, and conflict, a site where issues associated with Islam are mobilized to come to terms with the present state of the world. But how are aesthetics mobilized as a way of negotiating and contesting political, cultural, and historical circumstances? This chapter explores this question by conducting an analysis of two contemporary Indonesian art works: Membuat Obama dan Perdamaian yang dibuat-buat (2009) by Wilman Syanur and 11 June 2002 (2003) by Arahmaiani. Through their aesthetics the works evoke fragments from the past to question the construct of the present. This chapter shows how these aesthetic strategies form the base of a (Muslim) politics.

Keywords: Indonesia, contemporary art, politics, Islam, performance

In the world's most populous Muslim country artists are embarking on an approach to Islam and art that deviates from the calligraphy and the abstract images that are usually associated with the pairing of Islam and art.

– Bianpoen 2009In Indonesia, Muslim and non-Muslim artists show how visual culture, especially in a post-9/11 environment, is a site of Muslim politics, creativity, and contestation. Indonesian contemporary art constitutes a site where issues associated with Islam are mobilized to come to terms with the present state of the world. Contrary to calligraphy or abstract images – often called ‘Islamic art’ – the work of these artists typically lacks Islamic signs and figures, favouring figurative art. Nor does their work praise Islam, as calligraphy and non-figurative work frequently does. Rather, this form of contemporary art makes references to Islam to articulate political, social, and cultural dissatisfactions with the current state of the world. This art is therefore not called ‘Islamic art,’ but is a form of contemporary art that through its references to Islam or issues related to Islam can be seen as practicing Muslim politics. It is often through tactics such as provocation, parody, self-reflexivity, and humour that critique is expressed and politics are practiced.

These interpretations of art and Islam are part of a global trend. In the past few years, artists and curators worldwide have been exploring a fresh interpretation of contemporary art and Islam that moves away from abstract work. In 2006, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, for example, held a prominent exhibition of artists of Islamic heritage living in the West (Bianpoen 2009).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Globalization and Modernity in AsiaPerformative Moments, pp. 71 - 88Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2018