32 results

Chapter 6 - Joyce’s Racial Comedy

-

-

- Book:

- Race in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 121-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Modernist

- from Part I - Literary Periods

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Animals

- Published online:

- 26 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 112-131

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Decolonizing the English Department in Ireland

- from Part I - Identities

-

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing the English Literary Curriculum

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 42-59

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Walter Pater, Second-Hand Stylist

- from Part I - General

-

-

- Book:

- Walter Pater and the Beginnings of English Studies

- Published online:

- 14 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 133-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Cybernetic Aesthetics

- Published online:

- 10 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 1-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Hunger and Lust

-

- Book:

- Edible Arrangements

- Published online:

- 26 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2023, pp 60-99

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Molecular Shakespeare – Beckett Reading Shakespeare through Joyce

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Beckett

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 38-72

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 12 - James Joyce, Irish Modernism, and Watch Technology

- from Part III - Invention

-

-

- Book:

- Technology in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 201-216

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Irish Nationalism

- from Part II - 1945–1989: New Nations and New Frontiers

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature and Politics

- Published online:

- 01 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 150-164

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - “She Will Drown Me with Her”

-

- Book:

- The Persistence of Realism in Modernist Fiction

- Published online:

- 08 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 06 October 2022, pp 69-100

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 12 - Joyce’s Nonhuman Ecologies

- from Part III - Perspective

-

-

- Book:

- The New Joyce Studies

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 08 September 2022, pp 193-207

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Solastalgic Modernism and the West in Irish Literature, 1900–1950

-

-

- Book:

- A History of Irish Literature and the Environment

- Published online:

- 14 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 28 July 2022, pp 150-172

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Mutual Equality

- from Part II - Development

-

-

- Book:

- Globalization and Literary Studies

- Published online:

- 01 April 2022

- Print publication:

- 21 April 2022, pp 110-125

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 23 - Literary Modernism

- from Part III - Literary and Critical Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- Ralph Ellison in Context

- Published online:

- 14 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 02 December 2021, pp 250-259

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Two - Between Byzantium and Beijing

-

- Book:

- The Irish Expatriate Novel in Late Capitalist Globalization

- Published online:

- 29 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 11 November 2021, pp 84-130

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - The Double Consciousness of Modernism

-

- Book:

- Metamodernism and Contemporary British Poetry

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 117-133

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3.2 - Gothic, the Great War and the Rise of Modernism, 1910‒1936

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Gothic

- Published online:

- 29 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 19 August 2021, pp 43-60

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Contesting Wills: National Mimetic Rivalries, World War and World Literature in Ulysses

-

- Book:

- Modernism, Empire, World Literature

- Published online:

- 16 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 17 June 2021, pp 152-195

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - ‘A Wreath of Flies?’: Omeros, Epic Achievement and Impasse in ‘the Program Era’

-

- Book:

- Modernism, Empire, World Literature

- Published online:

- 16 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 17 June 2021, pp 243-275

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

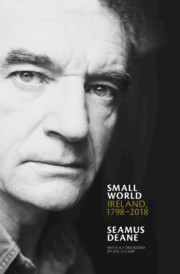

Small World

- Ireland, 1798–2018

-

- Published online:

- 03 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2021