44 results

Chapter 2 - The Engagement with Burke

-

- Book:

- Mary Wollstonecraft and Political Economy

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 50-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Myth of “Salutary Neglect”: Empire and Revolution in the Long Eighteenth Century

- from Part II - The British Colonies

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Age of Atlantic Revolutions

- Published online:

- 20 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 189-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Parliamentary Regime: The Political Philosophy of Confederation

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique / Volume 56 / Issue 3 / September 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 August 2023, pp. 550-570

-

- Article

- Export citation

3 - The Sublime in Eighteenth-Century English, Irish and Scottish Philosophy

- from Part I - The Sublime before Romanticism

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Romantic Sublime

- Published online:

- 06 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 20 July 2023, pp 41-52

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Conciliation after Hastings

-

- Book:

- The East India Company and the Politics of Knowledge

- Published online:

- 22 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 06 July 2023, pp 62-93

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Catharine Macaulay: Political Writings

- Published online:

- 23 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 March 2023, pp xi-xxxii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Observations on the Reflections of the Right Hon. Edmund Burke on the Revolution in France (1790)

-

- Book:

- Catharine Macaulay: Political Writings

- Published online:

- 23 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 March 2023, pp 251-300

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Observations on a Pamphlet entitled ‘Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents’ (1770)

-

- Book:

- Catharine Macaulay: Political Writings

- Published online:

- 23 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 March 2023, pp 109-123

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Indulgence

- from Part I - Political and Fictional Relations

-

- Book:

- <i>The Postsecular Restoration and the Making of Literary Conservatism</i>

- Published online:

- 22 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 22 December 2022, pp 67-100

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Essay, Enlightenment, Revolution

- from Part II - The Work of the Essay

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to The Essay

- Published online:

- 27 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 03 November 2022, pp 111-125

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Political Economy, the Family, and Sexuality

- from Part II - Contemporary Critical Perspectives

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Economics

- Published online:

- 28 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 163-178

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - The Sublime

- from Part II - Development

-

-

- Book:

- Nature and Literary Studies

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 161-176

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Commerce without Empire?

-

- Book:

- The Case of Ireland

- Published online:

- 27 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 February 2022, pp 59-99

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - The Enlightenment Critique of Empire in Ireland, c. 1750–1776

-

- Book:

- The Case of Ireland

- Published online:

- 27 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 February 2022, pp 23-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Enlightenment against Revolution

-

- Book:

- The Case of Ireland

- Published online:

- 27 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 February 2022, pp 139-173

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Jeremy Bentham on Historical Authority

- from Part I - Enlightened Historicisms

-

- Book:

- History and Historiography in Classical Utilitarianism, 1800–1865

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 23-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

History and Historiography in Classical Utilitarianism, 1800–1865

-

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021

2 - Republicanism

-

- Book:

- Foundations of American Political Thought

- Published online:

- 09 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 29 July 2021, pp 13-48

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 17 - Politics

- from Part IV - Philosophy

-

-

- Book:

- Frederick Douglass in Context

- Published online:

- 16 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 08 July 2021, pp 209-219

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

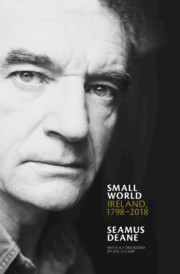

Small World

- Ireland, 1798–2018

-

- Published online:

- 03 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2021