46 results

‘A Star Lit by God’: Boy Kings, Childish Innocence, and English Exceptionalism during Henry III’s Minority, c. 1216–c. 1227

-

-

- Book:

- Thirteenth Century England XVIII

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 11 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2023, pp 125-146

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

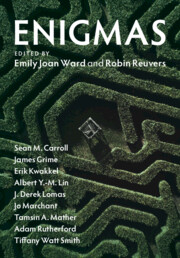

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp 1-9

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp xv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp vi-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp 229-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Enigmas

-

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022

Notes on Contributors

-

- Book:

- Enigmas

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 18 August 2022, pp xi-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Entering Adolescence

- from Part III - Child Kingship: Guardianship and Royal Rule

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 249-274

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Children and Kingship in the Early and Central Middle Ages

- from Part I - Royal Childhood and Child Kingship: Models and History

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 33-52

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - The Royal Deathbed

- from Part II - Royal Childhood: Preparation for the Throne

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 147-168

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface and Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp xi-xv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Feasting Princes?

- from Part III - Child Kingship: Guardianship and Royal Rule

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 230-248

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp xvi-xxi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Child Kingship: Guardianship and Royal Rule

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 169-282

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Royal Childhood and Child Kingship: Models and History

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 31-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Adapting and Collaborating

- from Part III - Child Kingship: Guardianship and Royal Rule

-

- Book:

- Royal Childhood and Child Kingship

- Published online:

- 04 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 201-229

-

- Chapter

- Export citation